INTRODUCTION

During the process of urban–rural integration in China, a new group of migrant workers with independent subject consciousness has been formed, and they are eager to know their own identity. However, migrant workers bear the challenges brought by structural pressure in the process of urban integration, due to the “selective” acceptance of modern cities, the identity division in the life interaction, the psychological division in the identification level, and the right division in the allocation of resources. “Migration” promotes great changes in the traditional family structure; however, the existing literature has paid limited attention to the family problems of migrant workers in China, only loosely related to low education level, low income, crowded living environments, small social networks of the floating population, etc. (Zeng and Zhang Reference Zeng and Zhang2006; Zhou and Chen Reference Zhou and Chen2015).

In the studies on domestic violence dominated by feminist theories, most focus on the female victims of spousal violence but less on the male victims. A limited number of studies have shown that male-on-female violence and female-on-male violence follow the same pattern (Chen and Xia Reference Chen and Xia2015; Ma Reference Ma2013; Migliaccio Reference Migliaccio2002). In addition, we usually focus on the factors related to the severity of domestic violence, but the critical point study of the onset of domestic violence is more important. Therefore, conducting a cross-sectional study on the families of migrant youth in the Pearl River Delta, this research attempts to identify the factors associated with the probability and severity of spousal violence with respect to both males and females, on the strength of the social exchange perspective.

THE SOCIAL EXCHANGE PERSPECTIVE OF “COST–BENEFIT” BETWEEN HUSBANDS AND WIVES IN MARITAL FAMILIES

In Social Behavior as Exchange, George Homans defined Social Exchange as an exchange activity of two or more persons’ tangible or intangible, more or less benefits and costs (Homans Reference Homans1961). According to the social exchange theory, human relationships are formed by the subjective use of “cost–benefit” analysis and comparison. The cost includes time and money, etc., and the benefit includes support, companionship, etc. Resources and power rely on each other in a family relationship. The interaction must make both partners feel fair and reasonable, and the exchange between costs and benefits keep balance, or resentment will accumulate, and violence will erupt. Many studies have found that domestic violence is related to social resource exchange status, and gender relations based on equal exchange of resources can reduce disputes and limit the intensity of conflicts, as people have stronger ability of punishing each other (Cai Reference Cai2005). In other words, given the high cost, most people are unwilling to use obvious coercion.

In fact, the exchange phenomenon of married life appears in the whole process of young men and women’s choosing spouse-marriage getting along. For example, older men often trade wealth and status for a woman’s youth and beauty, men earn money to support the family in exchange for full-time women doing housework, etc. However, sometimes family members want to do less while others do more, or even just enjoy the fruits of others without having toiled. Violence is likely to occur when one partner in a marriage wants to dominate the other at low cost, such as when a high-earning man abuses his stay-at-home wife in exchange for more obedience because she is too financially dependent to resist.

J. E. O’Brien, however, takes another view in his “status discrepancy hypothesis”, which focuses on the husband’s lower status due to his economic problems and educational differences (O’Brien Reference O’Brien1971). Violence is seen as a way to compensate for low status and boost self-esteem. Like all other social organs, the family relies on a degree of coercion and even threats to maintain its order (Goode Reference Goode1971). Straus and Gelles (Reference Straus and Gelles1986) and Giles-Sims (Reference Giles-Sims1985) explain the occurrence of domestic violence from the perspective of deviated family structure, claiming that the level of violence is the highest in families where the wife is the dominant partner. “People with real power don’t have to openly show their powerful influence in their interactions with others, while the powerless often bluff and scare people. This highlights that they feel the anxiety and tension in the face of incompetence or a sense of powerlessness, and use their little strength (violence) to bluff or gain a sense of control” (Cheng and Hsu Reference Cheng and Hsu1999). Those who have fewer resources adopt violence in order to maintain balance, such as lack of resources or power; for example, an unemployed man of low socio-economic status might be physically violent towards his wife with high social and economic status, to outmatch his wife, to realize the power of his inner feeling, and his wife also conceals her abuse experiences on the basis of “saving face”.

Based on the phenomenon of “cost–benefit” exchange between husband and wife, this study aims at exploring whether the equality of family status curbs the occurrence of spousal violence. Through analyzing the effect of age gap, income gap and education gap on spousal violence, the current study proposes the following research hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 Age gap increases the likelihood of the onset of spouse violence.

Hypothesis 2 Age gap increases the severity of spouse violence.

Hypothesis 3 Income gap increases the likelihood of the onset of spouse violence.

Hypothesis 4 Income gap increases the severity of spouse violence.

Hypothesis 5 Education gap increases the likelihood of the onset of spouse violence.

Hypothesis 6 Education gap increases the severity of spouse violence.

METHOD

Data Collection and Sample

This study was carried out in a district of China’s Pearl River Delta in 2017, which was an area with a large floating population, with the floating population accounting for 90%. In this study, 540,000 migrant workers in this area were taken as respondents. In the population database of this area, stratified random sampling was carried out on migrant workers aged 18–40 years old according to the random principle. The ratio of married men to women was 1:1. In all, 1268 valid questionnaires were collected and the valid response rate was 84.5%. The samples show that there are 664 floating males, accounting for 52.4%, and 604 floating females, accounting for 47.6%.

Measures

Dependent variable (DV)

The Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS), created by Murray A. Straus (Reference Straus1979), is the “most widely used instrument in research on family violence” (Straus and Douglas Reference Straus and Douglas2004). The DV module of this study is based on the modified version of the CTS (known as the CTS-2; Straus et al. Reference Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy and Sugarman1996) and conforms to national conditions in China, and the “yes or no” option is adopted to measure spousal violence in the past 12 months. Psychological violence consists of eight items: to complain about you; to blame you; to insult you; to throw things to you; to threaten to kill you; to destroy your favorite things; to intimidate you; and to track you (Cronbach’s α = .886). Physical violence is comprised of ten items: to throw something at you; to push or scratch you; to slap you; to kick or punch or bite you; to continuously beat you; to tie your hands and feet; to use sharp instruments to stab you; to burn you with cigarettes; to suffocate you; to throw vitriol at the wife or poison the wife or pour petrol on the wife or push the wife down the stairs (Cronbach’s α = .916).

Independent variable

The explanatory factors include age difference, income difference and education level difference between husband and wife. While some studies divide the relative resource differences between couples with equal rights as the reference group (Xiao and Feng Reference Xiao and Feng2014), most traditional studies make the difference between husband and wife absolute, that is, only the absolute distance between husband and wife on a certain variable in a particular relationship is measured. This approach ignores the possible directional differences in the asymmetry between husband and wife. In other words, the dominance of the husband in age, income and education level and the dominance of the wife have different effects on spousal violence. In order to correctly identify this difference in direction, the gap between the spouse’s and respondent’s information is taken, and three variables representing differences in age, income and education are obtained. These variables range from negative to positive. If the variable is positive and the absolute value is greater, this means that the spouse is greater than himself on this index. If the variable is negative and the absolute value is greater, this means that he is greater than his spouse on this index.

Control variable

In this study, three major indexes that determine an individual’s socio-economic status and affect the outcome of domestic violence are taken as control variables, namely, the age of the individual, monthly salary, education level (primary school, middle school, high school, junior college, undergraduate, graduate and above).

In addition, Freud’s theory of “childhood shadow” emphasizes the important role of childhood experience in the formation and development of personality. These childhood traumas, because of people’s self-protection mechanisms, are mostly suppressed in the subconscious area. Although we think the memories are no longer there, if they are accidentally touched by something, they will pop up and make people lose control of their emotions and behaviors. People learn behavior in childhood by observing violence between parents. Children often witness domestic violence, become accustomed to or allow the use of violence, rationalize the use of violence, and tend to deal with family disputes, stress and crisis in a violent way when they grow up (Miller-Perrin and Perrin Reference Miller-Perrin and Perrin2012). Therefore, this study will control the variable for “Witnessed inter-parental violence during childhood” and “Experienced child maltreatment by parents” and measure it through dichotomic variables.

Analytical Method

In this study, STATA 13.1 (StataCorp LLC) is used as a modeling tool. However, although many variables are frequency variables, their distributions do not completely follow Poisson distribution. Since spousal violence is a relatively rare event, the variable appears to exceed the number of zeros that the Poisson model can tolerate, so the zero-inflated Poisson model (ZIP model) is applied to assess which independent variable may affect the onset and severity of spousal violence. Statisticians view this distribution as a joint distribution of Bernoulli and Poisson (Lambert Reference Lambert1992), which is shown in the following formula:

$${\rm{f(x;p}},\mu ) = \left\{{\matrix{1-{\rm p} + {\rm pe}^{-\mu}, {\rm y} = 0 \cr{\rm pe}^{-\mu} {\mu^{\rm y} \over y !}, {\rm y} > 0}}\right.$$

$${\rm{f(x;p}},\mu ) = \left\{{\matrix{1-{\rm p} + {\rm pe}^{-\mu}, {\rm y} = 0 \cr{\rm pe}^{-\mu} {\mu^{\rm y} \over y !}, {\rm y} > 0}}\right.$$Therefore, in this study, the zero-inflated phenomenon is understood as the superposition of whether spousal violence occurs and the severity of spousal violence. The results of the ZIP model can be interpreted as two parts: logistic regression and Poisson regression. We try to use independent variables to predict the results of the above two processes respectively, so as to identify whether the independent variables involved in this study act on one of the above two processes or have an impact on both processes.

RESULTS

Sample Profile and Sample Differences

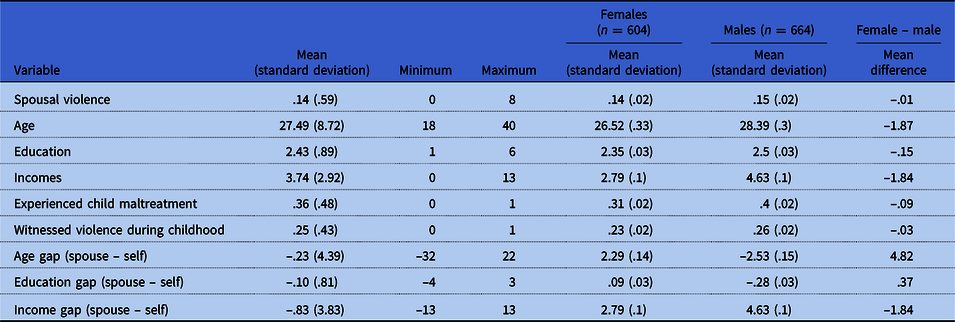

Table 1 shows that the average age of 1268 young migrant workers is 27.49 years old. The average education level is high school. The average salary is between RMB 2601 yuan and RMB 3100 yuan per month. The maximum value of spousal violence (18 categories in total) is 8, the minimum value is 0 and the average value is .14. This means that spousal violence is not serious or under-reported in this area.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Gender Difference Analysis of Samples (n = 1268)

According to the analysis of mean differences between the male and female youth samples, it is found that, compared with females, the average age, education level and monthly income of male samples are all higher than those of female samples. In childhood, males have more experiences of being beaten by their parents and witnessing violence between parents than females. In terms of violent experience, working women suffer more serious physical violence than men. The pattern of “male abusing female” is mainly reflected in physical violence, while the spousal violence of women against men is more reflected in psychological violence; in particular, women are more likely to complain, insult their husbands or track their husbands (as shown in Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Psychological Violence (n = 1268).

Figure 2. Physical Violence (n = 1268).

Zero-Inflated Poisson Model Analysis of Spousal Violence Influencing Factors

Traditional Poisson regression analysis shows that when a husband has a higher income than his working wife, the possibility of spousal violence suffered by the wife decreases (model 1). In other words, the higher a spouse’s income, the less likely a woman is to be abused. For both men and women, the smaller the educational gap between their spouses and themselves, the less likely they are to suffer spousal violence. If working women have been beaten by their parents in their childhood and men have witnessed violence between parents in their childhood, they are more likely to suffer spousal violence from their spouses when they become adults (Table 2).

Table 2. Regression Models of Marital Differences and Spousal Violence (n = 1268)

ZIP, zero-inflated Poisson; AIC, Akaike’s information criterion; BIC, Bayesian information criterion.

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses.

*p < .1; **p < .05; *** p < .01.

The ZIP model can be regarded as the logistic part and Poisson part, with the former as the probability of spousal violence modeling and the latter as the severity of spousal violence modeling. Model 2 shows that the greater the income difference between husband and wife, the lower the severity of spousal violence suffered by women will be (B = –.14, p < .01); that is, when the wage income of working women is significantly lower than that of their husbands, the severity of spousal violence suffered from their husbands is significantly reduced. When a woman’s education level is lower than her husband’s, the probability of spousal violence victimization will significantly decrease (B = –1.30, p < .01). This indicates that the result is contrary to hypotheses 4 and 5, when the husband’s income and education background are significantly lower than those of the migrant women, the risk of women suffering from spousal violence increases. However, age difference has no significant impact on female spousal violence victims. Therefore, hypotheses 1 and 2 are not supported by female samples.

Data on migrant male workers shows that the age gap between husband and wife affects the severity of spousal violence suffered by men. When the wife is older than her husband, the severity of spousal violence suffered by the man is lower (B = –.12, p < .05). When the wife’s education level is higher than her husband, the probability of violence by his wife is lower (B = –.99, p < .05). Women of older age and having received advanced education can reduce male workers’ risk of abuse. The male sample shows the opposite result of hypotheses 2 and 5. However, income difference has no significant statistical effect on male victims, and hypotheses 3 and 4 have not been verified in male samples.

However, the results of the ZIP model and Poisson model are different to some extent. The null hypothesis of Vuong’s test indicates the goodness of fit (GOF) of both the Poisson model and ZIP model are equivalent. In the current study, Vuong’s test reached statistical significance, which means that the null hypothesis is rejected and the ZIP model has a higher GOF than the Poisson model. This result indicates that the effects of some variables can be decomposed to different processes of spousal violence.

CONCLUSION

Based on the social exchange perspective, this study discusses the onset and severity of spousal violence in the husband and wife relationship of migrant families, and makes an in-depth analysis of the influencing factors of spousal violence between male and female migrant workers. The research findings are as follows:

(1) The Spousal Violence of Emerging Migrant Families Follows the Gender Symmetry Mode, and Males are Less Likely than Females to Report their Experiences as Spousal Violence Victims

Spousal violence does not occur very often, and is a small probability event. This study adopts stratified random sampling and follows the ZIP distribution. The findings reveal that spousal violence of emerging migrant families in this region is at a low level, and the occurrence probability of spousal violence is distinctly lower than that of other studies. This is quite different from the results of most other studies using optional sampling (Li and Jin Reference Li and Jin2012; Zhao, He, and Zhu Reference Zhao, He and Zhu2011; Zhou and Chen Reference Zhou and Chen2015). Similar to some studies, it was found that the victimization of males and females in marital conflicts follows a gender-symmetric pattern, with males and females equally likely to commit violence (Fiebert Reference Fiebert2014; Kimmel Reference Kimmel2002; Ma Reference Ma2013), and just female-on-male violence viewed as more acceptable. Violence against men is mainly reflected in psychological violence. Through the in-depth interviews, it was found that men are less likely than women to voluntarily report the experience of suffering domestic violence. They are mostly reluctant to expose their weaknesses, which is in accord with the dominant patriarchal culture in China. This has been confirmed in a few other countries’ studies (Chan Reference Chan2006; Courtenay Reference Courtenay2000; Tsui, Cheung, and Leung Reference Tsui, Cheung and Leung2010).

(2) Equality of Family Status is the Key to Prevent Females from Spousal Violence; However, the Pattern of “Cradle Snatching” and the Improvement of Women’s Education Level Make Men Fully Protected in Conjugal Relationships

Social pressure on migrant workers is usually higher than in other groups. As the social division of labor changes, women are more involved in the public space of social production, and sharing the family economic responsibility. Women’s roles have been irreversibly changed and their value is no longer only reflected in childcare and unlimited services to the husband. However, men are reluctant to share housework and childcare with women. At the same time, women also face the pressure brought by city integration and social adaptation. Based on the impact and challenge to the traditional patriarchal culture, when the husband’s income and education background are significantly lower than those of young working women, the risk of women suffering from spousal violence increases. In contemporary China, young working women are becoming independent. Yet in the skewed family structures of stressful societies, women’s education level and economic independence do not represent a protective factor against spousal violence from their husbands. The traditional patriarchal ideology is still the mainstream gender ideology in China’s urban cities. Patriarchal cognition is deeply rooted in the migrant families, even though the family pattern has changed and women’s status has improved in China. The social and economic advancement of females is a great challenge to the traditional male authority of family, and spousal violence also arises. This has been confirmed in previous studies: violence is more likely to occur in families dominated by the wife. The equality of family status is the key to curb female suffering from domestic violence. Violence is the husband’s choice to compensate low status and improve self-esteem.

For young migrant men, they are more likely to suffer psychological violence from their wives in traditional family patterns. The consequence also displays that living with an older wife is a protective factor in reducing spousal violence. The new pattern of “cradle snatching” makes men fully protected in conjugal relationships. It is very different from the custom in China, where a man should be two or three years older than a woman and such a marriage is seen as stable. The traditional family pattern has been broken. With the improvement of women’s overall education level, the daily conflicts caused by family trifles can be solved more reasonably, and men are fully protected in family relationships. The “unequal” status of age and education has become a protective factor to restrain the victimization of males, which is an interesting finding of this research.

To sum up, in the process of urban–rural integration, it is necessary for couples to negotiate and give consideration to others in the emerging families of contemporary young workers. According to his or her own ability and specialty, working hand-in-glove, the probability of spousal violence can be greatly reduced. Neither party will feel unfair or wronged for a long time. These will create a harmonious and happy family life.

The study has inevitable limitations. When the effects of independent variables on violent behaviors are decomposed into two processes, some variables may be effective on both the probability and the severity of violence. The opposite direction may be shown, which leads to no statistically significant results. This is probably caused by the insufficient sample size. Therefore, a more representative sample collection is required. Furthermore, this study attempts to measure gender differences in spousal violence. However, a spousal relationship is bidirectional. It cannot deny the possibility of two-way spousal violence, and the victim also acts as the perpetrator. Therefore, the problem of bidirectional violence between husband and wife needs to be explored in future research.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the Project of China Youth and Children Research Association (2019B24) and the Research Fund of Zhejiang Sci-Tech University (19102424-Y).

Xuan Chen is a lecturer in the Department of Social Work at the Zhejiang Sci-Tech University. She received her PhD from the University of Macau. Her research interests are intimate partner violence, victimology, correction and crime prevention.

Yiwei Xia is an assistant professor in the School of Law at the Southwestern University of Finance and Economics. He received his PhD from the University of Macau. His research interests include quantitative methods, juvenile delinquency and substance abuse.