INTRODUCTION: INTIMATE PARTNER HOMICIDES

Intimate partner homicides can be defined as killings in the intimate context. Perpetrators of intimate partner homicides can be former or current partners, and sometimes these killings are the ultimate expression of years of violence and control (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Nancy, Sharps, Kathryn and Bloom2007; Fitz-Gibbon et al. Reference Fitz-Gibbon, Walklate, McCulloch, Maher, Fitz-Gibbon, Walklate, McCulloch and Maher2018).

According to the most recent worldwide data, in 2017, more than one-third of women murdered were killed by an intimate partner, either former or current (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) 2018). In Europe, the percentage of women killed by an intimate partner is about 29%, the lowest percentage of all continents (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) 2018).

In Portugal, the Annual Report of Internal Security mentions that 19% of the 110 homicides committed in 2018 were perpetrated in the conjugal or similar context. This means, in absolute numbers, that about 22 homicides were committed in an intimate context, having 15 females and seven males as victims (Sistema De Segurança Interna (SSI 2019).

The Portuguese Observatory of Murdered Women (Observatório de Mulheres Assassinadas; OMA) of the Alternative and Answer Women’s Union (União de Mulheres Alternativa e Resposta; UMAR), a Portuguese non-government organisation, publishes data about femicides annually and referenced that, in 2018, the total of femicides in Portugal was 28, with 68% of those being in an intimate context (Observatório de Mulheres Assassinadas da UMAR (OMA-UMAR) 2019). This would correspond to 19 female victims killed by an intimate partner. As it can be noticed, values from the two sources are not the same. This might be because the Annual Report of Internal Security relies on official police information and their coding as homicide, whereas the Observatory has a daily newspaper as a source, including all cases of females killed by an intimate partner whether the crime was coded officially as homicide or not. Also, in newspapers the notices can be from the previous year (if published on January 1, for example).

Given the prevalence of intimate partner violence and extent of its consequences (not only for the victim but also for families and society in general), there has been an increasing interest to study further the phenomenon and improve policies so that it can become a preventable crime (Academic Council on the United Nations System (ACUNS) Reference Laurent, Platzer and Idomir2013; European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) 2017; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) 2018; Vienna Declaration on Femicide 2012).

Several authors have written about the importance of understanding intimate partner homicide characteristics and risk factors (Bridger et al. Reference Bridger, Strang, Parkinson and Sherman2017; Dobash et al. Reference Dobash, Dobash, Cavanagh and Medina-Ariza2007; Pais Reference Pais2010; Wilson Reference Wilson2005) but some other authors also highlighted the importance of analysing how these crimes are sentenced (Auerhahn Reference Auerhahn2007a, Reference Auerhahn2007b; de Agra et al. Reference da Agra, Quintas, Sousa and Lamas Leite2015; Grant Reference Grant2010). This paper aims to contribute to the understanding of the sentencing process of intimate partner homicides, especially those characterised as being “passionate crimes”.

CRIMINAL LAW AND INTIMATE PARTNER HOMICIDES IN PORTUGAL

In Portugal, crimes are codified in the Penal Code, which had a major reform in 1982. Intimate partner homicides are not a specific category of crime. When crimes are committed in intimacy and with intent, they can be charged and sentenced as simple homicide, qualified homicide or privileged homicide, depending on their characteristics and motives. There are several differences between these three legal types of homicides, including their sentencing framework.

Simple homicide is the most general category of homicide in which most of the homicides would fit. It carries a sentence of between 8 and 16 years of imprisonment (Article number 131, Penal Code). This is defined as the act of killing another person.

According to Article number 132 of the Penal Code, when the homicide is committed with “special censurability or perversity”, it might be qualified, and therefore the sentence framework is increased to a range from 12 to 25 years of imprisonment (which is the maximum limit for imprisonment in Portugal). Homicides perpetrated with special censurability or perversity are reasoned to reveal higher levels of blame than an average homicide would (Dias Reference Dias1987; Serra Reference Serra2000). In paragraph two of Article number 132 of the Penal Code, there are some examples that reveal the special censurability or special perversity of a homicide. Among these examples mentioned there are three of interest for this paper: (i) considerations about intimate relationships between victim and offender; (ii) considerations about actions determined by greed, by the pleasure of killing or causing pain, or determined by any other futile or clumsy motive; and (iii) considerations about criminal actions with a cold mind, with reflection about the means used in the crime or having persisted in the intention to kill for more than 24 hours (most commonly referred to as premeditation) (Serra Reference Serra2000).

As defined in paragraph 2 of Article 132, when the homicide is committed against an intimate partner, former or current, the level of guilt can be considered more severe and the sentence for the homicide can be that of a qualified homicide.

Homicide can also be considered qualified if the crime is determined by greed, by the pleasure of killing or causing pain, or by any other futile or clumsy motive. Courts and judges often must decide if intimate partner homicides could be considered crimes committed by futile or clumsy motives. Santos and Leal-Henriques (Reference Santos and Leal-Henriques2016) explain that clumsy crimes are those that offend the morality of a reasonable person, motivated for an abject, ignoble reason. These authors raise as an example of clumsy motive “the killing of a girlfriend by her boyfriend when he discovers that she is not virgin, or because she despises the offender” (Santos and Leal-Henriques Reference Santos and Leal-Henriques2016:71). A futile motive is a motive without a minimum of importance, frivolous. In Santos and Leal-Henriques (Reference Santos and Leal-Henriques2016), examples of intimate homicides are raised as motivated by futile reasons, namely killings due to the end of dating relationships and discussions between married couples.

Homicides committed with a cold mind or premeditated are also considered eligible to qualify the murder in the Penal Code (like other jurisdictions as Canada, for example). Cold-mind actions are those that could be described as in cold blood, made in a deliberate, calm and cautious way (Santos and Leal-Henriques Reference Santos and Leal-Henriques2016). Premeditation, in Portuguese law, is usually decided when actions were contemplated for more than 24 hours, but in some cases, shorter terms of premeditation are also considered. If a cold mind or premeditation is proved, intimate partner homicides can be sentenced as qualified homicides.

The last type of homicide to be considered as relevant to intimate context is the privileged homicide. This is a type of homicide, foreseen in Article number 133 of the Penal Code, with a lenient sentence due to the existence of an understandably strong violent emotion, desperation or a relevant social value that motivates the killing. Several authors argue that some sorts of provocations could be considered as causing a strong violent emotion, but these would have to be understandable by a reasonable person (Santos and Leal-Henriques Reference Santos and Leal-Henriques2016; Serra Reference Serra2000). It is worth mentioning that under the previous Penal Code (in force until 1982), provocation could be raised as a justification of the homicide in cases of adultery. This should be no longer accepted by courts. The existence of these strong violent emotions contributes to a significant decrease in the offender’s guilt, and therefore, the sentence framework for privileged homicides is lower – between 1 to 5 years of imprisonment.

After considering which homicide type is more appropriate to the situation and offender, the judge has to decide within the sentence framework which is the most appropriate sentence. In Portugal, specific sentences are decided taking into account the level of guilt of the offender and the prevention needs. According to Article number 40 of the Penal Code, under no circumstance can the offender be sentenced for a higher level of guilt than the one proved in the case.Footnote 1 Prevention needs are divided into general prevention needs and special prevention needs. General prevention needs are related to society and are assessed by the necessity to deter criminal experiences and to ensure society’s protection from that offender. On the other side, special prevention needs are related to that specific offender, his necessities of reintegration in society and also the deterrence of future crimes (recidivism) (Dias Reference Dias2013).

After considering the level of guilt and prevention needs, the judge has to decide the sentence – taking into consideration the mitigating and aggravating factors present in the case. The Penal Code provides a list of examples of these factors,Footnote 2 but no further guidance is available on how much they should mitigate or aggravate the sentence.

“Passionate Homicides” and the Portuguese Law

Intimate partner homicides are often named “passionate crimes” in the media and in common-sense expressions. Few studies have explored “passionate crimes” arguments, and even fewer have explored “passionate homicides” when related to jurisdiction practice and law (for one good exception, see Dawson Reference Dawson, Fitz-Gibbon and Walklate2016b).

Branco and Krieger (Reference Branco and Roberto Krieger2013) suggest as the most commonly accepted definition for “passionate homicides”: the ones motivated by passion. These crimes are often explained by the existence of uncontrollable feelings and emotions that disable the capacity of the offender to control his self-determination. Expressions like the offender “lost his mind”, “was blind of jealousy”, “was consumed by anger” and “was not able to think properly” are commonly present while describing the state of mind of the offender at the moment of the crime (Neves Reference Neves2008).

Emotions are natural expressions and responses of people to face the diverse situations of everyday life. It is expected that a reasonable person, without any psychopathology, when reacting to these emotions, would be able to control his/her actions. Even strong emotions are controllable, and that is why people are accountable for their own actions. Therefore, it is necessary to understand how these states of mind could influence the real capacity of the offender to determine himself/herself while committing a crime. It should be pointed out that, according to the literature, the “passionate” states of mind are not sufficient to constitute a defence for insanity or even to discredit legal accountability (Dressler Reference Dressler1982; Neves Reference Neves2008). Nevertheless, passion could sometimes be considered a factor that minimises the guilt of the offender. In Dressler (Reference Dressler1982), it is argued that some forms of provocation could lead to loss of control, and consequently to the perpetration of “passionate crimes”. This author also points to a question that is still current: is passion a justification or an excuse for the killing? (Dressler Reference Dressler1982; Neves Reference Neves2008).

“Passionate crimes”, or “passionate homicides”, are not categories of crimes foreseen in the legal nomenclature in Portugal. Passion was never encompassed in the Portuguese Criminal Law. Still, some courts and judges use these common-sense expressions to explore some sorts of crimes.

Homicides described as “passionate homicides” are mainly associated with intimate relationships, and the most common question is whether passion is considered an emotion that mitigates or aggravates the crime. First, it is essential to mention that “passion” is not enough to argue for the exclusion of guilt, and consequently, for legal lack of accountability under the psychic abnormality foreseen in the Penal Code. Homicides described as “passionate crimes” are not considered a result of a psychic abnormality (Neves Reference Neves2008). This means that offenders who perpetrate crimes under “passionate emotions” are liable for their actions. The question afterword is related to which types of defences could be raised related to this state of mind, and which of these would be accepted. Privileged homicides are a less blameworthy type of homicide because they are committed under the influence of an understandable violent emotion. Is it possible that this violent emotion is passion? Despite the few empirical studies addressing it, it is argued that it might be that the defence tries the “passion” for being considered a violent emotion. However, this violent emotion would have to be understandable to the level of a reasonable person. Moreover here, time, cultural and social changes might have an impact, given that what was understandable a few years ago might not be understandable nowadays. As an example, it can be recalled that, under the first version of the Portuguese Penal Code, the husband could kill his wife if she was caught in obvious adultery, which is not something accepted presently (Fermino Reference Fermino2012).

There are few studies on passion and how passion is (not) accepted in the Criminal Law. The most cited book by the Portuguese jurisdictional practice is a monography published in 2008 by João Neves entitled (in English) The Problematic of Guilt in Passionate Crimes. In the final remarks of this book, Neves argues that “Despite an assumption still current, the passionate murderer does not kill for love, at best he kills for his love for himself.” (Neves Reference Neves2008:715) This point of view is interesting, given the background history of these so-called “passionate killings”. As Branco and Krieger (Reference Branco and Roberto Krieger2013) concluded, “passionate homicides” are unique, not only because of the emotions involved in the killing, but also because of the history of the relationship between victim and offender that often includes other forms of violence and control.

The study of these “passionate killings”, their arguments, and how these arguments are perceived by courts is fundamental to understand how these “passionate” homicides are being sentenced. According to Dressler’s (Reference Dressler1982) review, “passionate killings” were treated more leniently than the “cold-minded” killings. As the author asks, what is the reasoning on this sentencing decision? Could it be related to the dangerousness of these two types of offenders? Moreover, which should be considered more dangerous? The one who commits the crime with a cold mind and premeditation or the one that cannot control himself and kills as a result of strong emotion? (Dressler Reference Dressler1982).

SENTENCING INTIMATE PARTNER HOMICIDES

Sentencing studies on intimate partner homicides are developing progressively. Some of these studies have been focusing on the differences between sentencing intimate and non-intimate partner homicides (Auerhahn Reference Auerhahn2007a; Dawson Reference Dawson2012, Reference Dawson2016a, Reference Dawson, Fitz-Gibbon and Walklate2016b; Dawson and Sutton Reference Dawson and Sutton2017; Karlsson et al. Reference Karlsson, Tuulia, Kaakinen and Antfolk2018), while other studies have focused specifically on the impact of characteristics of the offenders, victims or crimes on sentencing (Grant Reference Grant2010; Johnson, Wingerden, and Nieuwbeerta Reference Johnson, Sigrid Van and Nieuwbeerta2010).

Intimacy between victim and offender is a factor that often mitigates the gravity of the homicide, when compared with non-intimate homicides (Auerhahn Reference Auerhahn2007b; Dawson Reference Dawson2006; Miethe Reference Miethe2006). Dawson (Reference Dawson, Fitz-Gibbon and Walklate2016b) identified that one of the most common stereotypes about intimacy and violence present in judicial discourses is that the offender’s culpability is reduced by the existence of “mitigating emotions” that undermines their capacity to deliberate their actions. The same author suggests that intimate partner homicides are often named “passionate” and “hot-blooded” despite the fact that they are more frequently premeditated than homicides in a non-intimate context (Dawson Reference Dawson2006).

In a study about sentencing trends on males who kill intimate partners, Grant (Reference Grant2010) found that previous domestic violence was very commonly described in these sentences and that the degree of overkill was also high. A great part of the most serious killings analysed (first-degree murders) were premeditated and involved estranged spouses, with the accused committing the crime due to his anger over the split.

The first empirical study on sentencing intimate partner homicides in Portugal was based on decisions from first instance courts (de Agra et al. Reference da Agra, Quintas, Sousa and Lamas Leite2015). From this study, it is possible to conclude that most homicides were sentenced as qualified (63.3%), having an average term of imprisonment of 18.42 years (standard deviation = 2.23 years). In 72.6% of these cases, the qualification of homicide involved the intimate relationship between victim and offender. In 41.9% of the qualified homicides, a cold mind or persistent intention to kill was present and in 12.9% futile motive was considered a qualifying factor. About one-third of the crimes were premeditated, and in about 40% of the crimes, immediate precipitants related to the non-acceptance of the end of the relationship were involved (de Agra et al. Reference da Agra, Quintas, Sousa and Lamas Leite2015).

There are no studies in Portugal that explore homicides named as “passionate killings” by the court, arguments used by the defence and the outcomes of these arguments in the sentencing process. This paper aims to contribute to filling this gap.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this paper is to analyse whether or not intimate partner homicides are described as “passionate crimes” in the Portuguese Judicial System and, if so, who describes them as “passionate”: the defence or the Supreme Court of Justice (SCJ)? This paper will also discuss the patterns present within these “passionate” arguments and how the SCJ responds to them.

METHODOLOGY

This paper is part of broader research on sentencing intimate partner homicides, and is based on decisions reached by the SCJ. This court, the highest court of Appeal in Portugal, has the responsibility of unifying jurisprudence. This sentencing study is based on the decisions of SCJ, specifically those in which “passion”, “passionate crime” or “passionate homicide” arguments were invoked.

Data Collection

As explained in the topic overview, intimate partner homicide is not an autonomous crime, and therefore there are simple homicides, qualified homicides and privileged homicides (and attempts, respectively), all of which can occur in the context of intimacy.

The method of selecting the appropriate cases was threefold: (a) keyword search in the juridical database of the SCJ;Footnote 3 (b) summary search from the SCJ cases; and (c) citation of similar cases within the sentences. The first step was a keyword search in the online database with expressions that are commonly used as “descriptives” of these sentences.Footnote 4 The second step was to read the summaries of all the homicide cases between 1996 and 2018, from the official summary report available on the SCJ’s website; and to gather all those that were in an intimate context. The third step was to identify citations of similar cases from those cases already collected and analysed.

The sentences that emerged from data collections were read and included only if they met the inclusion criteria: (a) crimes had to be homicides or attempted homicides with intention (no insane cases were included); (b) victim and offender had to be intimately related at some point; (c) appeals were related to the crime (and not, for example, with financial compensation); and (d) it was clear that the crime was in an intimate context. The sentences with insufficient information, where it was not possible to conclude about the intimacy context, were not included. All decisions between 1984 and 2015 that met the criteria were collected and saved.

From this data collection, 304 cases were identified, with only 181 available online. Given the focus of the paper, not all cases are of interest: only those in which arguments of “passion” were raised. A text search for “passion” or “passionate” was done. The cases were read, and those that were available online and had arguments related to “passion” were selected for a more in-depth analysis. This selection resulted in a total of 24 cases.

Data Analysis

The analysis that this paper proposes is a qualitative analysis of “passionate” arguments, how they are related to other feelings, and how the SCJ deals with these arguments. For a better understanding of the victim, offender and crime characteristics, a brief general description of the cases was included using quantitative data.

Quantitative data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) with variables that were related to the victim, offender, the relationship between victim and offender, crime, sentence, appeal arguments and SCJ decisions. For the purpose of this paper, 23 variables related to the offender, victim, their relationship and the crime’s characteristics were analysed.

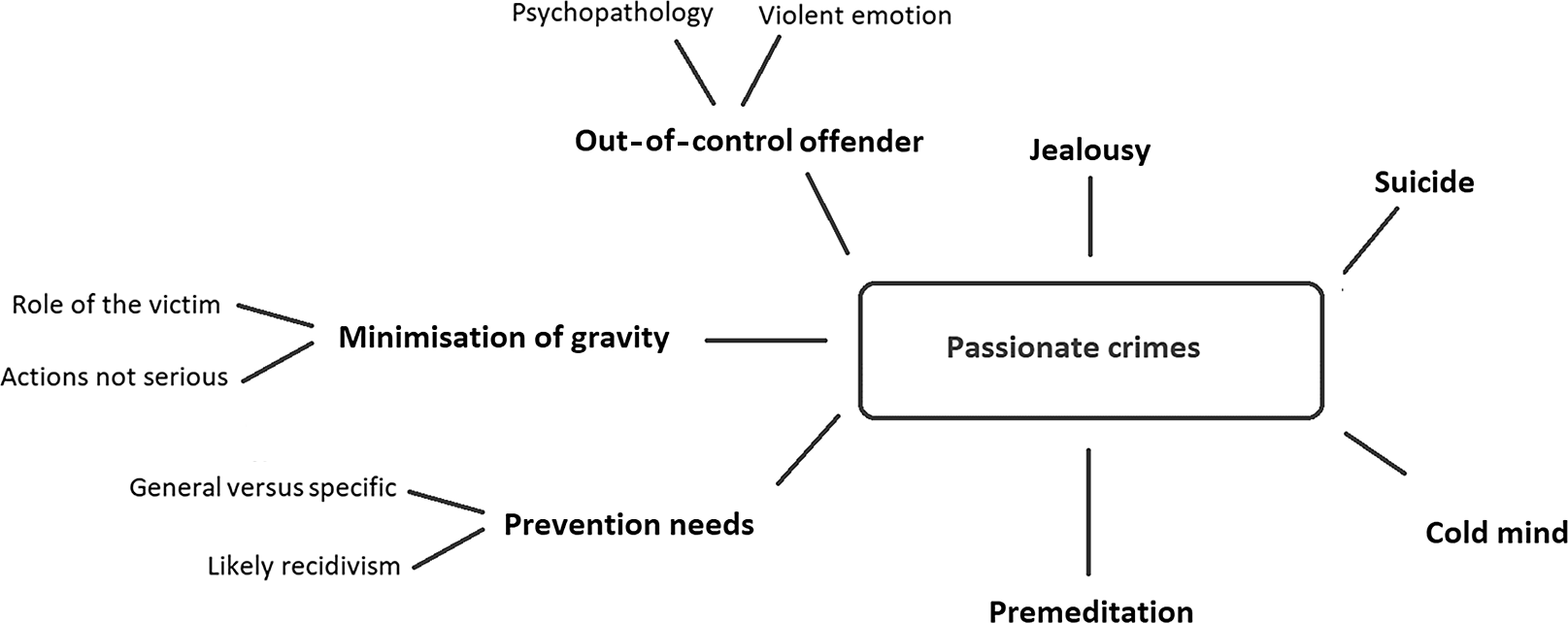

Sentences were analysed with the assistance of the program NVivo. All expressions related to “passion” were coded into one of the two following categories: “appeal arguments about passion” or “Supreme Court of Justice arguments about passion”. Seven other themes were found to be relevantly related with “passion” arguments (as shown in Figure 1): minimisation of gravity of the offence; out-of-control offender; jealousy; suicide; cold mind; premeditation and prevention needs. Each of these themes and its relationship with “passionate crimes” will be further explained in the Results section, through the use of quotes. Quotes were translated from Portuguese to English by the researcher. As in any translation, the punctuation and the word order had to be altered so that the content can be understandable in English.

Figure 1. Codes and themes qualitatively explored in this paper.

RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

The result and analysis section is organised in three subsections: (I) General description of the cases; (II) “Passion”: a mitigating factor?; and (III) “Passion”, likely recidivism and prevention needs. The first part is to characterise the cases, and it is mainly quantitative, and the following two sections are based on the qualitative analysis of the sentences.

General Description of the Cases

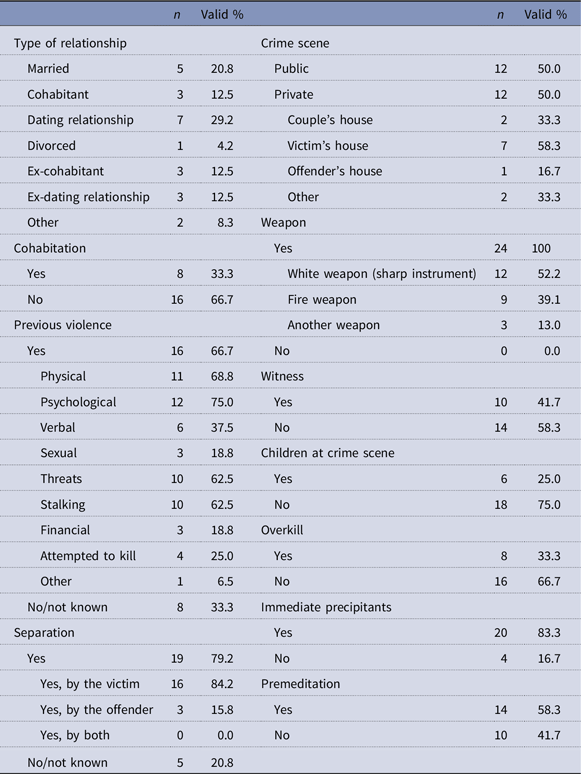

Table 1 provides the results regarding some of the sociodemographic characteristics of the victims and offenders.

Table 1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Offenders and Victims

Most offenders were male (91.7%) with the same percentage of female victims (91.7%). Only two cases had a female offender and a male victim (8.3%). In more than half of the cases, the age of the offender is unknown. When age is known, the mean is 38.10 years (standard deviation = 12.78 years), the youngest offender being 23 years old and the oldest, 57 years old. The mean age of the victims was just below 35 years old (standard deviation = 9.7 years, range 20–48 years). Marital status of both victim and offender were dispersed. In the case of the offender, the highest percentage is married (33.3%). The category that had a higher number of victims was dating relationship (29.2%). It is essential to mention that this marital status is independent of the relationship between victim and offender. The offender might be married to someone else that is not the victim and have an extramarital relationship with the victim. A criminal background was present in seven of the 24 offenders (31.8%), with none related to domestic violence. In the case of the victims, none had a known criminal background. Five offenders had problems with substance abuse (31.2%), and two of the victims had similar abuse problems (12.5%). Suicide attempts by the offender were present in six of the 24 cases (25%), the most considerable part of these suicide attempts being after committing the victim’s homicide (83.3%). There was no information about previous attempts of suicide by the victim.

When considering the relationship between victim and offender, as presented in Table 2, it is possible to conclude that the most common type of intimate dynamic is the dating relationships (29.2%), followed by the married couples (20.8%).

Table 2. Relationship and Crime Characteristics

The largest proportion of intimate couples were not living together at the time of the crime (66.7%) and had a history of previous violence in the relationship (66.7%). Threats were present in 62.5% of the cases where previous violence was possible to identify, and previous attempts to kill the victim were present in a quarter of the cases (25.0%). Separation or attempted separation was present in 19 of the 24 cases, corresponding to 79.2% of the intimate partner homicides. In 16 of these, the separation was intended by the victim, and in three by the offender. It is worth to note that from these three cases where the offender was the person who aimed for the separation, two of them were female offenders who were victims of domestic violence by their male partners.

Half of the crimes were perpetrated in public spaces like parking areas, or desert locations (50.0%) and the other half were in private spaces (50.0%). The victim’s house was the most common private crime site (58.3%), followed by the couple’s house and other private locations (33.3% in each). Other private locations included sites such as friends’ houses and a victim’s lawyer’s office.

Weapons were involved in 100% of the cases, white weapons (sharp instruments) being the most common weapon type (52.2%). In 10 of the cases, there were witnesses present (41.7%), and in six of the 24 cases, children witnessed the crime (25.0%). OverkillFootnote 5 was identifiable in eight cases (33.3%), as for example in one case when the offender killed the victim with 35 stabs. Often there were immediate precipitants of the offence and premeditation at the same time. Immediate precipitants were present in 20 cases (83.3%), and the most common were not accepting the end of the relationship (10 cases) and suspicion of infidelity (nine cases). Premeditation was present in 14 cases (58.3%) and the most common evidence of premeditation was related to taking the weapon to the crime scene (10 cases), threat to kill the victim and describing how he would accomplish it (five cases) and stalking the victim, waiting for the appropriate moment to kill (five cases).

“Passion”: A Mitigating Factor?

When the concept of “passionate crimes” is analysed, it is immediately possible to understand that in a significant number of cases it is the defence who raises the “passionate crime” argument to mitigate the gravity of the offence and, consequently, the offender’s level of blame. In 13 of the 24 cases, “passion” was used by the defence to explain why the offender should have a lenient sentence rather than the one given by the court that is being appealed. The arguments used by the defence relating “passionate crimes” were deemed to consider this an extreme form of emotion causing the offender to be out of control, minimising the gravity of the homicide – because it was related to “passion”.

These defence arguments, exploring “passion” as the reason for the offender to be “out of control” while committing the homicide, were usually replete with expressions relating to the loss of control:

Given the constant vows of eternal love, the defendant felt completely “lost”, “adrift” and with a feeling of unbelief, while she [the victim] takes his clothes and tells him that she will put him on the street because she no longer wants him. (Appeal argument, sentence dated May 21, 2018, case number 08P1522)

In another case also related to loss of control, the defence referred that “passionate crimes” caused an incapacity to react according to the law, given the loss of rationality:

In this type of crime – the crime of passion – the agent is impelled by passion and the overwhelming feelings overpower lucidity and reason and, thus, leads the agent to commit the crime. (Appeal argument, sentence dated March 18, 2015, case number 351/13.4JAFAR.E1.S1)

In both these sentences transcribed, the SCJ did not accept the “passion” as an element for minimisation of blame. In one of them, in which the offender stabbed the victim (mentioning that if she was not his, she would not be anyone’s), the SCJ argued:

The fact that the motive of the crime is passionate since it was committed immediately following the “repudiation” of the defendant by the offended person, it does not imply any diminution of criminal responsibility. (SCJ argument, sentence dated May 21, 2018)

In two cases, the loss of control is related to psychopathy, and the defence argues that the “passion” and love for the victim caused a pathology leading him to lose control. This is argued in two cases (dated 2002 and 2012) where the offenders claim that they had a “passionate chronic delirium of jealousy” and a “paranoid psychosis of jealousy”, respectively. In both cases, the SCJ did not accept the psychopathology as a mitigating factor given that these offenders were considered liable for their crimes by the psychiatry experts.

Jealousy is often closely related to the “passion” argument. Defendants argue that the “blindness of jealousy” caused them to commit the crime, driven by a strong and uncontrollable emotion. The response of the SCJ to the jealousy is, generally, clear:

The accused invokes as a mitigating cause of his responsibility the jealousy that he was possessed, and that we are in the presence of a crime of passion, but he has no reason, because jealousy does not act as an excuse for the agent of crime (…). (SCJ argument, sentence dated March 18, 2015, case number 351/13.4JAFAR.E1.S1)

Despite this general position of not accepting jealousy as an excuse of non-responsibility, in some cases, this jealousy is understood as a cause of a strong and understandable emotion that might help to establish a causal link between the crime and previous actions:

The defendant was overwhelmed by an understandable violent emotion at the moment of the practice of the facts, an emotion consubstantiated by the fact that his wife was in bed with her lover, co-author of adultery, who was his brother-in-law, his godfather and his friend (…) [the defendant] motivated by these understandable and strong violent emotions, practised the facts, thus having between the facts and the emotions a causal link – it was the strong emotion that led him to commit the crime and lost his discernment leaving him in an emotional state – passion that dominated him. (SCJ argument, sentence dated September 18, 1996, case number 96P008)

As quoted, jealousy is usually not accepted as a mitigating factor, but it is discussed in jurisprudence as a possible motive that could be considered a futile crime under the qualified homicide, and therefore increase the severity of the sentence. This was only raised in two cases and the SCJ declared that “passion crimes” are not crimes with a futile motive:

The jurisprudence of the Supreme Court of Justice has ruled on the motivation of a passionate type, specifically on jealousy considering that this is by no means a futile motive (…) It is well known, in fact, that jealousy involves an instinctive dimension that, according to some, is sometimes related to a feeling of fear of loss, real or imaginary, that would reveal a lack of confidence and low self-esteem and may assume characteristics of obsessive disorder aspect… (SCJ argument, sentence dated April 15, 2015, case number 176/13.7JAFAR.E1.S1)

In some of the cases where suicide is attempted, the defendants contend that this suicide is the last evidence that the crime was committed under the loss of control and self-determination. In one of the cases, the fact that the agent attempts to commit suicide is used to explore the possibility of considering this homicide as a privileged homicide, and therefore decrease the sentence severity. In this particular case, the discussion between the victim and the offender was triggered by the fact that the victim refused to do what the defendant wanted (to live with him in another city). According to the defence:

It is understandable that a lover, mentally weak and poorly educated, let himself be guided by violence and despair when the woman, object of his passion, with whom he shared the project of living together (without drugs and morally irreproachable), after sexual intercourse, tells him that she will continue to drug and prostitute herself and engage in physical confrontation, insulting him and pushing him. The defendant’s subsequent behaviour (staying close to the corpse for about 1 hour and only then realising that she is dead and attempting suicide from the top of a high-voltage post) reveals the state of great emotion and despair that significantly diminishes his fault. (Appeal argument, sentence dated March 6, 2003, case number 02P4406)

The SCJ did not accept these arguments and decided for a sentence of simple homicide, convicting the offender to 10 years of imprisonment.

In another case where a suicide attempt was identifiable, the SCJ mentioned that the “suicide completes the typical framework of passionate crimes” (SCJ argument, sentence dated October 3, 2007, case number 07P2791), but, again, does not accept it as a mitigating factor.

Minimisation of the gravity of the offence is another strategy used by the defence to argue for the mitigation of the sentence. In one of the cases, the defence argued that the victim was somehow involved in the final result. In this case the SCJ accepted the role of the victim in the crime, mentioning that the crime was:

…a disturbance that affected the defendant’s will, as a result of an emotional context of confrontation with the victim, in which the victim’s death is a consequence of a pathological relationship in which the passivity of the defendant is contrasted with the depreciative attitudes of his partner. On this circumstance, one can converge in the affirmation of the existence of a conflictive environment in which levels of consideration and mutual respect were successively violated until reaching a phase of exasperation of feelings that can reach the will. (SCJ argument, sentence dated May 18, 2011, case number 24/10.0PAMTJ.L1.S1)

This sentence mitigated the crime due to the emotions involved in it.

Another sentence dated June 1, 2016, when “passion” is analysed, the SCJ mentions that there is a “strong intensity of guilt, putatively mitigated by the passional motive, but strongly increased by the ostensible contempt of the dignity of the woman” (case number 1707/14.OJAPRT).

One of the other defence strategies are related to diminishing the gravity of the crime based on the fact that the crime itself was “passionate”. This was visible in the following appeal:

…the degree of unlawfulness is medium since the crime was committed passionately, it can even be said in a rudimentary way since there was no use of instruments other than those used by the defendants in their daily activities… (Appeal argument, sentence dated November 30, 2017, case number 3071/15.1JAPRT.P1.S1)

In this case, the defence classifies the crime as rudimentary, not very serious given the instruments used (an axe and a knife) and the fact that “passionate homicides escape reason and logic, but often confirm the frenzy and violence of a passion” (Appeal argument, sentence dated November 30, 2017, case number 3071/15.1JAPRT.P1.S1). The SCJ did not pronounce a sentence exclusively on this specific argument, but increased the severity of this sentence.

“Passionate homicides” are often characterised as crimes committed in the “heat of the moment”, right after a discussion. Therefore the defence often argues that these “passionate crimes” are not premeditated, neither carried out with a “cold mind” (like the one that would qualify the homicide in the Portuguese Judicial System). This defence strategy was identified in three of the appeals. In one of the cases, the offender was living in London. When he realised his estranged wife had a new intimate relationship, he decided to come back to Portugal to kill both of them; but still, the defence argued that the crime was not in a “cold mind” but a result of “passion”. Responding this case, the SCJ mentioned that:

Defendant’s behaviour indicates that he decided to kill the woman in advance, moving from London to Lisbon and from there to the victim’s home, and once within the empty house, made all preparations for the execution of the crime. Defendant acted with cold mind, entering the house as planned, passing by the gunsmith and taking out a weapon (…), entering the victim’s room, leaving to return to the gunsmith and change weapons, re-entering the victim’s room and not being deterred from killing the woman even in the presence of her son (…). (SCJ argument, sentence dated May 18, 2011, case number 24/10.0PAMTJ.L1.S1)

“Passion”, Likely Recidivism and Prevention Needs

A theme that revealed to be of great importance in this research is the need for prevention and its association with the considerations of “passionate homicides”. The defence argues that offenders that commit “passionate homicides” are not dangerous; or a threat to society and have little possibilities of recidivism:

(…) the accused cannot be tried and considered as a dangerous individual with impulsive, obsessive and aggressive behaviour, when in fact he has no criminal record. All his life, he had conduct according to law, only have been different, in this situation, punctual, which by the way, takes passionate contours. (Appeal argument, sentence dated January 14, 2016, case number 562/12.0PCMTS.P2.S1)

The most common response to these arguments from the SCJ is the affirmation of high prevention needs, particularly general prevention, with a few cases also mentioning the importance of the special prevention needs:

[when considering the aggravating factors it is important to consider] the guilt of the defendant and the requirements of general prevention, of deterrence, taking into consideration the frequency with which crimes of this type (with a passionate weight) are repeated in our society – and also of the special prevention itself – given that the defendant never assumed to have practised the essential part of the proven facts. (Appeal argument, sentence dated October 25, 2006, case number 06P1286)

When the defendant’s characteristics and the possibility of recidivism are considered, it is interesting to note that the defence argues that these offences cannot be considered part of a criminal plan and that offenders could not be taken as having a criminal career. The SCJ usually accepts these two arguments when it concerns criminal characteristics of the acts and offenders. This has even a more significant impact if it is considered that in one of the crimes, with a sentence dated July 15, 2008 (case number 08P816), the offender was convicted of attempted homicide and argued that there was no “cold mind” in his actions. All forms of domestic violence were involved in the previous history of this couple, including rape, abduction and previous attempts to kill the victim. Premeditation was present in this case, and the offender shot the victim twice, in the head. In this case, the SCJ reduced the cumulative sentence of the 10 crimes that this offender was being judged for, even when considering the extreme circumstances of its commission, stating that:

It is quite certain that the defendant is of young age (precisely 28 years) and that the practice of the mentioned crimes was due to passionate reasons, but in which he manifested violent tendencies, reducing the other to a “thing” and not hesitating to resort to all methods to achieve his selfish ends. It is not an auspicious beginning of life, but it cannot be said that the action he manifests, (…) can be informing that he has a criminal career tendency (…) It may well be that all this crime is part of a particular stage of life. (SCJ argument, sentence dated July 15, 2008, case number 08P816)

In conclusion, it is essential to reaffirm that the SCJ is aware of society’s prevention needs (general prevention). This can be due to the increase of awareness about intimate partner homicides and gender-based violence in general. All cases mentioned the importance of having a fair sentence for the general prevention needs of deterrence. The transcription below was chosen as illustrative of the awareness and preoccupation of the SCJ to maintain the respect of human rights:

(…) the time has passed when so-called “passion crimes” were accepted with indulgence. Social relations have changed in recent decades, with particular emphasis on the relationship between spouses, whether in homosexual relations or in heterosexual relationships (…), emphasising equality between the two spouses and, above all, recognition of the inalienable right of every individual, regardless of sex, to choose his or her way to model their life according to their sense of happiness, to make a relationship cease when it ceases to satisfy him. In this sense, it is said, today, that there are no vows of eternal love, this pattern of life being internalised in the community. (…) True love is generosity, capacity for selflessness, respect for the choices of the other and abdication of one’s well-being for the well-being of the other person one loves, even though it would cost the sufferer much to feel unloved. You cannot force anyone to live with us, much less to love us. Otherwise, it is our feeling that is rooted in a will of empire and totalitarian rule. But if one is not able to have this understanding of things, at least the inherent human dignity of each person, which is a fundamental principle of our constitutional order of values, with all the consequences it entails, must be enough to ward off any interference so invasive and destructive in the sphere of decision and action of the other. (SCJ argument, sentence dated September 26, 2013, case number 641/11.0JDLSB.L1.S1)

DISCUSSION

Using a number of intimate partner homicide cases judged by the Portuguese SCJ it was possible to conclude, similarly to what was debated by Dressler (Reference Dressler1982), that “passionate” arguments can sometimes be used as justifications of the crime, and other times, as excuses. This author points out that “courts have often failed to coherently state which doctrinal path is involved” when sentencing these crimes and sometimes even “rationalised the doctrine under both theories” (Dressler Reference Dressler1982:438). The reason for this study to use SCJ cases was to contribute to the knowledge of the most satisfactory judicial decisions on this topic.

The question raised concerns the consequences of the “passionate” arguments presented to the SCJ.

First, it is important to highlight that most of the “passionate” arguments were raised by the defence to minimise the gravity of the crime and the level of guilt of the offender. These arguments are commonly followed by descriptions of out-of-control offenders that sometimes do not fit the characterisation of the crime (Dawson Reference Dawson, Fitz-Gibbon and Walklate2016b). In this study, several offenders who had premeditated their offences argued that the crime was hot-blooded, and that they could not control their own actions because they were “consumed” by this strong “passion” emotion. This argument does not hang together with the high percentage of premeditated intimate partner homicides, 58.3% in this study. Out-of-control defences are also not easily linked with previous death threats to the victim or with the high number of cases in which the offender takes the weapon to the crime scene. Most of the actions described in these sentences are not “out of the blue” as discussed by Dobash, Dobash, and Cavanagh (Reference Dobash, Dobash and Cavanagh2009), but cautious actions. Intimate partner homicides are frequently crimes committed deliberately, and even in the cases where premeditation was not involved, that does not mean the offender did not think about a possible killing before. It does only mean that premeditation was not raised or proved on court.

Psychopathy was also raised as a possible excuse for this crime, but as Neves (Reference Neves2008) pointed out, “passionate” emotions are not considered a psychic anomaly, and therefore defendants are liable for their actions. In this study, all offenders were liable for their actions and psychopathy was not accepted by the SCJ.

The real motive of “passionate homicides” is quite often related to the need for power and control above the intimate partner. In Grant’s (Reference Grant2010) sentencing study from decisions of the Supreme Court of Canada, separation and killing of estranged wives were also evident. In the current study, 10 of the immediate precipitants present just before the killing were related to the non-acceptation of the end of the relationship, while nine were related to suspicion or knowledge of another intimate relationship. Dreher and Angonese (Reference Dreher and Angonese2014), through interviews with convicted offenders, also concluded that the feelings mostly involved with the killings were jealousy, revenge and hate. Despite the fact that jealousy is not usually accepted by the SCJ as an excuse for homicide, in one of the cases it was found that the situation in which the offender was in (feeling jealous and angry due to a betrayal) was relevant enough to provide a “causal link” between the offender and his actions. Therefore, it might be reasonable to conclude that notwithstanding jealousy not being accepted as an excuse for the homicide, sometimes it is accepted as a justification for it.

The literature reviewed emphasises that some crimes related to intimacy, namely those that result from the end of dating relationships, should be classified as driven by futile motives, and therefore sentenced as qualified homicides (Santos and Leal-Henriques Reference Santos and Leal-Henriques2016). Nevertheless, in this study, “passionate homicides” were not considered driven by a futile motive. Justifying this, SCJ judges mentioned that futile crimes should be without motive or with a motive without a minimum of importance, frivolous. In these crimes, judges considered that a clear motive is present: the jealousy, the fear of losing the intimate partner, and the wish to continue an intimate relationship with their partners. Further studies and reflections should be developed to understand which motives are being considered futile under the Portuguese Criminal Law and precisely how does this relate to the crimes committed by “passion” or crimes perpetrated in intimacy.

One of the conclusions to be drawn from this study is that defences argue that these offenders are not dangerous, have little possibility of recidivism and the SCJ agrees that these offenders do not have a propensity for a criminal career. This was discussed in Miethe (Reference Miethe2006) who found that varying conceptions about dangerousness between intimate and non-intimate offenders led to different outcomes when sentencing. Having in consideration that in 66.7% of the cases analysed in this study, previous domestic violence was involved and that, as mentioned, 58.3% were premeditated, it is not possible to agree that these offenders are not dangerous. It is clear that by criminal careers, the court is referring to a criminal diversity or the same crime committed several times. In this analysis, 31.8% of the offenders had a criminal background and none related to domestic violence, nor to the crime which was being sentenced at the SCJ. Nonetheless, when analysing intimate partner relationships, most of which involved previous domestic violence histories, the focus should be on the risk of these offenders to continue disrespecting their intimate partners. Domestic violence is usually a continuous crime, that is not extinguished in only one offence. A domestic violence victim might suffer hundreds of violent acts. Still, for the criminal purpose, domestic violence counts as one crime. It is also worth mentioning that in 62.5% of the cases, victims were previously threatened to be killed and that 25% suffered from an actual killing attempt. Also, the characteristics of the crimes, often involving more violence than necessary to kill, named as overkill (33.3%) and the use of weapons (100%), reveals that these offenders are, actually, very dangerous particularly when victims (intimately related) do not comply with their desires. Just the fact that the offender does not have a reported criminal background does not mean they are not dangerous. If there is evidence (as reported in sentences) that previous domestic violence was present, it is because that person is somehow deliberately engaged in criminal acts, and therefore it should be considered there is propensity for a criminal career (that might not be diverse in types of crimes, but is still extremely intense). These results and discussions were similarly presented in Dawson (Reference Dawson, Fitz-Gibbon and Walklate2016b), in which the author identifies that in 38% of the analysed sentences, the court highlighted that these offenders do not constitute danger to society because their crimes were isolated “crimes of passion”.

When prevention needs are considered, general prevention needs were addressed by the SCJ in all cases. All sentences considered intimate partner homicides to be crimes that society cannot accept.

CONCLUSION

First, the authors would like to conclude this article by calling attention to the use of the expression “passionate homicides”. Passion is, by definition, a good emotion, an intense feeling of interest, attraction, enthusiasm and desire. Calling intimate partner homicides “passionate crimes” minimises their gravity, shifts the focus of the crime, and almost trivialises the killing. At the same time, the use of “passion” as an adjective to homicide is also to withdraw the positive emotions that passion is supposed to raise. Perhaps the use of “passionate homicides” should be avoided and, as a consequence, all homicides would be better interpreted as a result of a deliberate action against the life of another person.

Relatively little attention has been given to the role of “passionate” arguments in sentencing intimate partner homicides (Dawson Reference Dawson, Fitz-Gibbon and Walklate2016b). This study contributed to the existent research on sentencing and focused especially on “passionate” arguments raised in the Portuguese SCJ. From the analysis of 24 judicial decisions, two main conclusions can be raised. The first conclusion is that the defence usually argues that “passion” is an emotion removing the self-determination of the offender, making him out of control. This argument is usually not accepted by the SCJ as a mitigating factor in the judicial decision process. The second conclusion is related to the characterisation of intimate partner homicides by the SCJ and its lack of criticism on the dangerousness of these offenders and potential criminal careers. Generally, the SCJ identifies that intimate homicides are serious and essential to prevent but agrees with the defence by saying that these offenders are not particularly dangerous. This is arguable given than most of these offenders were engaged in a previous long history of domestic violence, sometimes involving several and severe forms of violence, including previous killing attempts. It would be valuable to assess the consistency of these findings across other countries and with a complete database (and not only the cases that were available online). The impact of time, social and legal changes would also be interesting as further studies (Dawson Reference Dawson2016a; Grant Reference Grant2010).

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on a broader PhD research project funded since March 2020 by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology), Ministry of Education. The project title is: “Sentencing intimate partner homicide: a comparative study between Portugal and England” (reference SFRH/BD/144774/2019).

Catia Pontedeira is a lecturer in Criminology at the University Institute of Maia, Portugal. She is currently conducting a funded PhD research in Criminology at the Faculty of Law of the University of Porto with the title: “Sentencing intimate partner homicide: a comparative study between Portugal and England” (funded by FCT, reference SFRH/BD/144774/2019). She is involved as a senior researcher in a recent project named “Study on Factors that Facilitate Witness Reporting of Intimate Partner Violence”, funded by the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE), and has experience in national and international projects about gender-based violence.

Jorge Quintas, PhD in Criminology, is an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Law, University of Porto. He is currently director of the School of Criminology, and a researcher in CJS (Crime, Justice and Security) at the Interdisciplinary Research Centre of the School of Criminology. His recent scientific interests include evaluative research on domestic violence programmes, sentencing studies, risk assessment, and offender rehabilitation, and the effects of drug regulations.

Sandra Walklate is Eleanor Rathbone Chair of Sociology, Liverpool University, UK conjoint Chair of Criminology, Monash University Australia. She is internationally recognised for her work on criminal victimisation which has over time become increasingly focused on violence against women. Her most recent book with colleagues at Monash University is Towards a Global Femicide Index: Counting the Costs published by Routledge in 2020. She is currently President of the British Criminology Society and received their outstanding achievement award in 2014.