INTRODUCTION

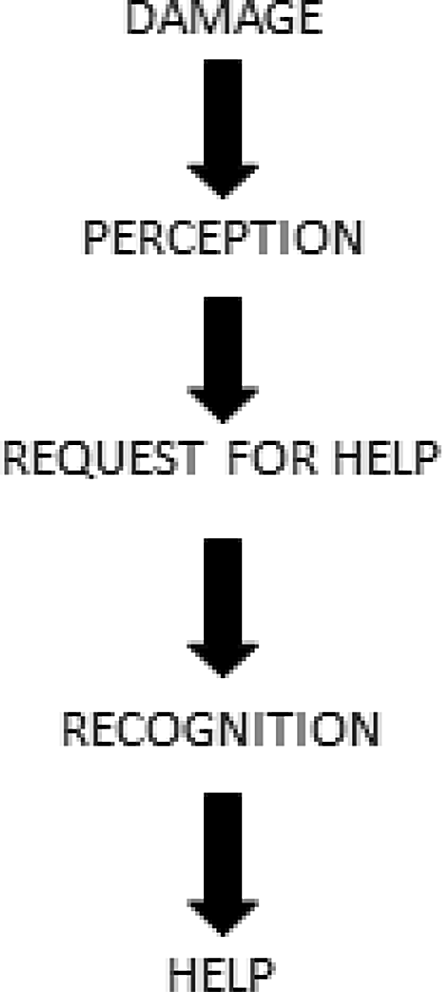

Emilio C. Viano defined the victim of a crime as being: “any subject injured or that has suffered wrongdoing on the part of others, who perceives herself to be a victim, who shares the experience with others looking for help, assistance and compensation, who is recognized as a victim and who presumably is being helped by the public, private or collective organizations” (Viano Reference Viano1983:150; Reference Viano, Balloni and Emilio1989:56).

The elements that make up the definition of a “victim” are, therefore, according to Monzani (Reference Monzani2013a):

-

(1) the damage sustained;

-

(2) the perception of victimization;

-

(3) the request for help;

-

(4) the ratification;

-

(5) the assistance (aid).

(1) The Damage Sustained

Damage refers not only to financial damage, only viewed in monetary terms, but to any form of damage, from financial, to physical, biological, psychological, and moral, as well as the much discussed and now reformulated existential damage. Fortunately, in recent years, it has become more apparent that wounds that do not bleed (emotional wounds) are often more painful than wounds that do bleed (physical wounds) (Amodio et al. Reference Amodio, Bondonio, Carnevali, Galli, Grevi, Pisani and Rubini1975; Gulotta Reference Gulotta1976; Gulotta and Vagaggini Reference Gulotta and Vagaggini1981; Ponti Reference Ponti1995).

(2) The Perception of Victimization

Many subjects suffer unfair treatment but, for various reasons (cultural, religious, social, etc.), they do not perceive themselves as victims; not only do some of these not view themselves as victims but also, sometimes, they tend to blame themselves for the situation in which they have to live and put up with (Eliacheff and Lariviere Reference Eliacheff and Lariviere2008; Monzani Reference Monzani2010; Vezzadini Reference Vezzadini2006; White and Gilliland Reference White and Gilliland1977).

An obstacle to awareness is without doubt represented by a cultural system of silence, that legitimizes and justifies the victimization, that presents such behavior as tolerable or as “not so bad after all…”; this complicates a situation which is already in itself complex and painful in itself (Adami, Basaglia, and Tola Reference Adami, Basaglia and Tola2002).

The difficulty of recognizing victimhood may arise from an unconscious ideology. Due to the preponderant cultural norms and how people, especially women, are socialized and taught their rights and role, some victims cannot imagine alternatives to their situation, so they do not have the opportunity to rebel (Testoni Reference Testoni2007).

(3) The Request for Help

Sometimes the victims, fearing retribution or reprisals that may be worse than the actual abuse, tend not to report the abuse, even though they know their rights, and, more generally, tend not to ask for help. They may have sunk into a strange reality that legitimizes their status, becoming “accustomed” to living in a situation of unjust suffering and submission, and rather than risk making the situation worse, they prefer to continue living a life of pain, at least “secure” in knowing what will happen tomorrow. In many societies, including advanced ones, there is no safe mechanism for recourse and protection; and domestic violence or physical violence towards children is not recognized as a crime.

Victimization is a “dynamic” experience that evolves in a particular way; it is not an instantaneous experience, even when it is, unfortunately, no longer a vague possibility but a living reality.

To start a “liberation path” from a state of victimization (whatever that may be), it is necessary to create appropriate financial and social situations, in order to implement and sustain the project and the path itself.

(4) The Ratification

The ratification, suffice it to say, the “formalization” of the status of the victim on the part of the relevant institutions, is a necessary prerequisite before the victim may benefit from the help and the facilities provided for by law and which are reserved for those who meet the criteria for this category (Monzani Reference Monzani2011a; Reference Monzani2012).

(5) The Assistance (Aid)

If the victim does not report the situation in which she is living, and/or if the persons around her do not recognize her status as a victim, the victimization and the blame could be increased and thus multiply the effects.

Often the first help provided by significant figures re-establishes in the victims a sense of trust in society and in the people close by, and this helps them to take that indispensable step towards overcoming the situation; that is by reporting it to the authorities (Saponaro Reference Saponaro2004). A failure to overcome the acute phase of the victimization means that the victim risks having to live all of her life, or a good part thereof, with difficulties that may powerfully limit her self-realization. Or more simply, that might impede her from living a “normal” life; in a word, to quote the World Health Organization – that could provoke a significant worsening in the quality of life.

As it can clearly be seen, a victim is someone who experiences harm (that could be of a physical, psychological, economic or moral nature, etc.) caused by an unfair action against him/her from a third party, and who is aware of having suffered an injury.

Thanks to this experience, victims may approach official control agencies for help who, in acknowledgement of their status as victims, enable their access to assistance, to gain release from the vicious loop of victimization.

THE EXPERIENCE OF THE ITALIAN ANTI-VIOLENCE SUPPORT CENTERS

The model described by Balloni and Viano (Reference Balloni and Viano1989) (see Figure 1) represents a linear model that starts from the suffered harm, recognized in some measure as unjust and undeserved, and ends with the overcoming of the victimological status, through the acknowledgement and the confirmation of their condition.

Figure 1. The model of Balloni and Viano (Reference Balloni and Viano1989)

The experience in the Italian Anti-Violence Support Centers, set up around 30/40 years ago and based on the American feminist and victim–witness programs experience, has enabled a closer examination of the path of victimization undergone by women who suffer domestic violence.

In particular, it has been observed that on top of an individual’s perception of his/her victimization, it is the very request for help itself and the application for help to the Anti-Violence Support Centers which trigger the victim to embark on a path of self-awareness.

It can be said that talking about perception means talking about impressions or intuitions, while raising awareness is not a simple notion, nor mere knowledge, but a condition in which the perception and knowledge of an issue are internal, deep and in perfect harmony with all the other dimensions of the person.

Becoming conscious of the situation in which a person is placed marks a fundamental step in the right direction: it allows one to face and re-elaborate one’s experiences.

As seen, the awareness occurs gradually following a path composed of different stages which allow access to other successive stages.

The first step concerns developing an awareness of the damage that he/she feels, or rather, being conscious of “feeling bad”.

Then the victim should become aware that what she suffered is undeserved and unjust. It may be the equivalent of a crime, and so there is the chance of her being protected by the law. The third and final step of the path toward full awareness is the exit awareness also known as the realization of a woman of the possibility of getting out of this situation.

This is how the experience in the Anti-Violence Support Centers made us think of a Circular Model of Victimization (CMV) (see Figure 2) in which every step of the path of awareness corresponds to a step on the helping path, until leaving the circuit of violence.

Figure 2. Circular Model of Victimization

The first stage (damage awareness) mainly requires psychological assistance, the second stage (crime awareness) mainly requires juridical assistance, while the third stage (exit awareness) instead demands assistance of a mainly clinical and therapeutic approach.

During all those steps, it is essential to take into account other demands of the victims: placement in refuges (for her and for any minor children) usually managed by Anti-Violence Centers, physical protection, material and financial support to make the victim independent from her perpetrator, etc. As regards financial independence, the Italian Anti-Violence Centers increasingly organize and coordinate professional training courses to teach women victims of violence how to learn a trade and achieve economic autonomy, without relying only on financial subsidies. Besides, many projects are aimed to link the victim with the workplace, to facilitate as much as possible the path of liberation from the situation of victimization.

The theorized CMV needed verification and, along with my team from the SCRIVI Center of IUSVE University of Venice, I conducted a research into all of the 120 Anti-Violence Support Centers present in Italy (Monzani and Giacometti Reference Monzani and Anna2018). The aim was to verify if the Centers’ operators recognize the different steps assumed in the theoretical model shown above, in their daily work, and therefore if this model could be considered as an actual empirical model.

It should be clarified right away that domestic violence can also be perpetrated by the female subject against the male subject, just as the dynamics of intra-family violence are almost identical in homosexual couples. This means that it would be more appropriate to speak of “relational violence” (Monzani Reference Monzani2016; Monzani and Giacometti Reference Monzani and Anna2018) rather than gender violence, as the gender of the subjects involved represents only one of the variables (and often not even the most important). Furthermore, it is important to underline that male subjects suffering from domestic violence find it more difficult to find formal control agencies able to support them and help them, unlike female subjects for which, as we have seen, anti-violence centers were established a few decades ago.

The research carried out, and presented below, only concerned violence against women, as it involved the Italian Anti-Violence Centers, which deal exclusively with this form of violence.

THE RESEARCH

The research was entitled “The Inner Application of the Circular Model of Victimization and Clinical–Juridical Approach in Italian Anti-Violence Support Centers as perceived by their staff. Promoting Teamwork” (Monzani and Giacometti Reference Monzani and Anna2018).

Issue definition and hypothesis formulation are:

-

Purpose: the possible spread of teamwork as it is defined in the light of the Clinical–Juridical Approach;

-

Aims: verifying the different ways of teamwork adopted in the Anti-Violence Support Centers, in particular, where their procedure follows the Clinical–Juridical Approach;

-

The theoretical perspective: the CMV and the Clinical–Juridical Approach.

The hypotheses of the research are:

-

1. When a woman turns to an Anti-Violence Support Center, she may be only partially aware of the damage suffered;

-

2. When a woman turns to an Anti-Violence Support Center, she may be only partially aware of the crime suffered;

-

3. When a woman turns to an Anti-Violence Support Center, she may be only partially aware of the exit possibility from her victimization status;

-

4. Damage awareness occurs through a prevailing psychological source;

-

5. Crime awareness occurs through a prevailing juridical contribution;

-

6. Exit (freedom) awareness occurs through a clinical and therapeutic contribution;

-

7. Teamwork is not intended as a clinical–legal approach;

-

8. The opening of an Anti-Violence Support Center allows women to obtain awareness and, therefore, leads to an increase in the number of requests for help.

The research was carried out via e-mail by submitting a questionnaire containing 70 questions to the 120 Anti-Violence Support Centers. A total of 50 replies came back, an excellent result given the complexity of the questionnaire, the internal organization of the Italian Anti-Violence Support Centers, and their relationships with institutions and surrounding territories. The amount of answers made the research into an “observational study”; it consists of an epidemiological and analytic study in which a researcher does not determine the subjects’ distribution in the groups, but only limits him or herself to take note of what is happening.

THE QUESTIONNAIRE

There were 70 open and closed questions, with a prevalence for the closed ones.

Questions were split up into nine sections: Center organization, operators’ formation, activities offered by the Center, inter-institutional net, the first transmission to the Center and activities’ organization, awareness path, help path, teamwork, and final considerations.

The purpose was to suggest some possible ways of improvement concerning the current work of the Anti-Violence Support Centers, especially concerning the operators’ formation and the real teamwork.

Now we will examine the main questions and the respective answers that emerged.

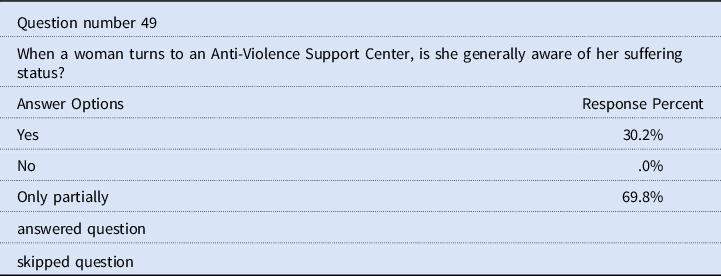

Question number 49: When a woman turns to an Anti-Violence Support Center, is she generally aware of her suffering status?

Question number 50: When a woman turns to an Anti-Violence Support Center, is she generally aware of being a victim of a crime?

Questions 49 and 50 show that the majority of women who turn to an Anti-Violence Support Center in Italy are only partially conscious of the harm suffered and how this harm corresponds to a form of criminal offence.

Question number 51: When a woman turns to an Anti-Violence Support Center, is she generally aware that it is possible to exit from her victimological status?

Question number 51 explains how women have only a partial perception regarding exit awareness.

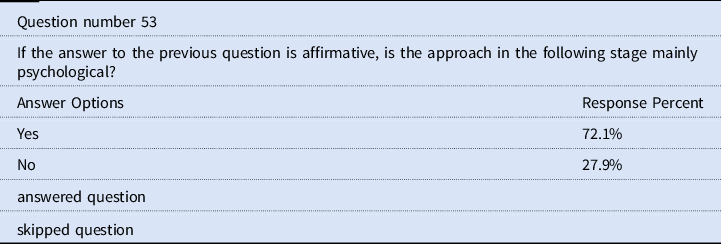

Question number 52: Does the helping path start with the woman’s awareness about her status?

Question number 53: If the answer to the previous question is affirmative, is the approach in the following stage mainly psychological?

The answers to questions number 52 and 53 confirm that the first stage of the awareness path is mainly psychological.

Question number 54: Does the helping path continue with the woman being aware of being the victim of a crime?

Question number 55: If the answer to the previous question is affirmative, is the approach at this stage mainly juridical?

The answers to questions number 54 and 55 confirm that the second stage towards awareness is mainly juridical.

Question number 56: Is the path towards the exit from the victimological status determined by a mainly psychotherapeutic and juridical approach?

Question 56 confirms – even if only partially – that the third stage of the awareness path is mainly clinical–therapeutic.

Obviously, beside a psychological and psychotherapeutic support, other variables, linked to victim’s requirements, have to be taken into account: physical protection, financial support, chances of employment, etc. All of those elements contribute to the victim’s exit from the victimization’s circuit, as soon as possible and in the best way.

From question 57 to 68 we asked the Anti-Violence Support Centers if they worked as a team and if teamwork was promoted.

Question number 57: When meetings with the psychologist occur, is the lawyer (at least partially) present?

Question number 58: When meetings with the lawyer occur, is the psychologist (at least partially) present?

Question number 59: After a meeting with the victim, do the psychologist and the lawyer have an exchange of views?

Question number 60: Do the psychologist and the lawyer have a general exchange of views also with the Center’s operators?

Question number 66: Do you think that teamwork is enhanced in your Center?

Question number 67: Do you think that teamwork represents an added value to the activities conducted?

Question number 68: Examining teamwork, do you think that there is room for improvement?

Although almost all of the Centers claimed to work as a team, from the analysis of the given answers it emerged that, according to the Centers, such practice consists of weekly or monthly meetings between the operators to discuss the different situations. However, our concept of teamwork presupposed that all the operators work together and, at the same time, with the woman victim, on the way in which everyone takes part in every single stage of the awareness path. Therefore, teamwork, as we mean it, is not taking place in these Centers.

Question number 69: Was the Center created on precise requests of the territorial demand?

Question number 70: Does the opening of the Center increase the help requests?

Questions 69 and 70 were aimed at understanding whether the Anti-Violence Support Centers open when the territory needs them to or as new Centers opened, the local demand went up. The answers, almost unanimously, showed that requests for help from women increased when the Centers opened, which confirms that the Anti-Violence Support Centers fulfill a fundamental role in the awareness campaign for women who suffer violence; it brings the subject to a perception of victimization which is fundamentally important in making the first application for help.

THE CIRCULAR MODEL OF VICTIMIZATION–REVISED

The main conclusions we have come to are the following: the CMV is confirmed, and teamwork is not the one envisaged by the clinical–legal approach.

A very important factor came to light as a result of the research: the concept of perception presented by Emilio C. Viano in Reference Viano1983 does not clash with the basic awareness concept of the CMV as previously outlined, but, on the contrary, these two ideas complement each other.

As a matter of fact, research shows that most of the women who turn to an Anti-Violence Support Center have a vague consciousness of what they have been subjected to – as Viano asserts: the perception of the damage, of the injustice, of not deserving to be treated that way, and of the need for an exit. What has also been witnessed is that approaching the Anti-Violence Support Centers allows those simple perceptions to be transformed into real awakenings which are vital for coming out of circular violence.

Here then, we present how the CMV can be re-examined in the light of the research conducted (Monzani Reference Monzani2019) (see Figure 3):

Figure 3. Circular Model of Victimization Revised (Monzani Reference Monzani2019). Y, yes; N, no; Neg., negative; Pos, positive; PSY, psychological assistance; MAT, material help

As we can see, the path to awareness is no longer based on three stages, but on four by adding a first stage that consists of the perception and awareness of a risk. Risk is taken to mean a dangerous situation, the chance that something bad might happen, the possibility of danger, injury or emotional hurt, often depending on unpredictable situations.

To each moment of perception there follows a stage of the helping path that brings the subject to full awareness and so there will be a new perception that takes the subject to another stage of the helping path, and so on until the exit from violence.

The research just introduced has enabled us to consider the CMV – both in the original and revised versions – no longer as a theoretical explanation, but as a valid empirical model which founds its confirmation in the reality of the Italian Anti-Violence Support Centers.

HOW TO READ THE NEW CIRCULAR MODEL

The perception (or awareness) of risk opens the door to a possible path of prevention which, if successfully concluded, will avoid future victimization of the potential victim. For the sake of completeness, it should also be noted that if the prevention pathway is not started, it will not necessarily lead to certain victimization, although there is a high probability that it will (Monzani Reference Monzani2019).

Each moment of perception (of risk, damage, crime, and exit) will be followed by an aid path stage that will lead to full awareness, and from here to a new perception that will lead to a new stage of the aid path and awareness, and so onwards until the final exit from the circuit of violence.

Specifically, according to Monzani (Reference Monzani2019):

-

(1) The perception of the damage leads the victim to a first request for help which will lead to a recognition of the damage suffered, a recognition that will lead to full awareness of the damage. In this phase the contribution of the operator will be mainly psychological;

-

(2) The perception of the crime leads the victim to a second request for help which will take the form of recognition of the legal status of victim, which will lead to full awareness of the crime; at this stage the operator’s contribution will be predominantly of a legal nature;

-

(3) The awareness of the crime will lead to a third request for help that will accompany the victim towards a perception of the exit, i.e. the perception that, perhaps, a solution to get out of the situation of victimization exists. In this phase the contribution of the operator will be mainly psycho-legal;

-

(4) The perception of the exit will lead the victim to a fourth request for help, which will lead to the full awareness that it is possible to get out of that situation, an awareness that will guide the victim towards an exit from the circuit of violence. In this phase the contribution of the operator will be mainly clinical–legal (Monzani Reference Monzani2019; Monzani and Giacometti Reference Monzani and Anna2016). The other needs of the victim must be taken into account, such as those linked to the presence of minor children (they could accompany the mother to refuges, if necessary), or concerning financial independence of the woman from her abuser, or moreover requirements linked to material support, like house or work needs.

It is clear that it is the perception of injustice, of “not deserving it”, that puts us on the path through the request for help, but it will then be the request for help which allows the full development of awareness. This justifies the inclusion, in the revisited circular model, of the stages of perception; stages theorized by Viano in his linear model, and not considered by the circular model in its first version.

This path must be clear to those who will have to work with victims of violence, in particular those who will have to take in women in an Anti-Violence Center. The operators must be well aware that they will be faced with people who, at most, will have a simple perception of what they are suffering, and who will need a path of awareness and help that will have to be developed in stages, through a clinical–legal approach. This involves a well-structured team working between the different operators, an approach that victim assistance centers are still struggling to develop and implement, despite their perceptions and assertions.

It is essential to underline once again that teamwork, as intended by the Clinical–Legal Approach (Monzani and Giacometti Reference Monzani and Anna2016), is fundamental for the development of the path, that should not be understood as a set of stages disconnected from each other, but as a real “path”, a journey that aims to connect the individual stages.

Beyond the metaphor, this means that the individual stages must be very closely linked and this can only be done through teamwork that must not consist only of sporadic meetings between operators, but must envisage these involved in the different stages of the help process. Specifically: during the phase of becoming aware of the damage, mainly psychological in nature, the participation of other professional figures in addition to the psychologist is important.

In fact, one must not only operate in order to make the victim understand that what he/she is suffering corresponds to a case of crime, but (above all) also try to find the best solution for that particular person, in that particular situation, and at that particular time.

The legal solutions that will be feasible will presumably be more than one; the objective of this phase will be to choose, together with the victim, the solution that best suits the individual situation.

For example, the best solution for a woman who suffers violence may not necessarily be to report her case immediately to the police; in some cases, this solution is not the best one, others being preferred.

It is clear that the choice, together with the victim, of the most appropriate path for the individual situation, will be assessed in consultation – for example, between the legal counsel and the psychologist; and, if there are children, also with the social worker, etc.

This is because the choice of the legal path to follow must necessarily take into account the consequences of a psychological nature related to the experiences that the victim will have to face (e.g. listening, complaints, testimonies, etc.), beginning with the important issue of the so-called second victimization (Monzani Reference Monzani, Arcidiacono, Testoni and Groereth2013b), but not only that.

It is important, therefore, that the legal path that the woman victim of violence will have to choose, together with the operators of the Center, takes into account all factors (including psychological ones), that must necessarily enter into the assessment of the choice of the path.

Each passage to the next stage must take into account the different factors and variables that will arise and also an overall view of the path already travelled, as well as the variables and consequences of a psychological, legal, and clinical nature, and practical considerations (e.g. safe residence, financial needs, etc.).

CONCLUSION

In recent years, victims are becoming progressively better organized and recognized and have attracted the attention of society and of public opinion, as well as that of institutions, achieving great results (Monzani Reference Monzani, Arcidiacono, Testoni and Groereth2013b).

Now it is necessary to consolidate the above-mentioned results, whilst guaranteeing help to the victims by ensuring the presence of a local/national support network (public, private and/or private/social), helping and guiding them by means of the appropriate services, adequately financed and staffed by specialized personnel. If this is not the case, a false expectation could be created in the victim (who will wait in vain for the requested help) that will then go unheard, provoking further suffering and disillusionment – the so-called third victimization (Monzani Reference Monzani2011b).

In addition, this may stimulate important legislative reforms in order to adapt the legal framework to the changing common conscience (one need think only of the recent reforms regarding sexual assault, or of the laws regarding so-called stalking).

To be able to implement these networks of solidarity and support for the victims of abuse, it is necessary to have an adequate allocation of funds from the government (maybe using part of the assets seized from the convicted perpetrators of the abuse), otherwise the law, even though excellent, risks becoming meaningless, representing nothing more than a declaration of intent. If this happens, future victims, seeing the failure to provide the requested help to the previous victims, will tend to go back to the practice of not reporting the abuse suffered, thus provoking a regrettable and painful re-victimization, not to mention an undesirable return to the past (Monzani Reference Monzani, Arcidiacono, Testoni and Groereth2013b).

The long-term objective is for the Centers to strengthen and build up their teamwork to implement more efficient action in favor of victims who apply to them for help.

Lastly, a more ambitious goal is to create other Anti-Violence Centers, addressed to all the people suffering violence, regardless of gender. In fact, violence is more related to cultural and relational factors than to gender-related issues (although present), and most of violence’s dynamics finds its origin and explanation (that is not an excuse) in the relational aspects involving protagonists, regardless (or almost) of the gender.

The objective is therefore to tackle, combat and prevent violence in the same way for every person who suffers it.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Chiara Gaffo, Arthur Lowe and Carlotta Ribotti for helping with the final review of the paper.

Marco Monzani is the Director of the Master’s Degree in Criminology and of the University Center for Studies and Research in Criminological Science and Victimology (SCRIVI). He is Professor of Criminology, Victimology and Forensic Psychology, Degree in Psychology, IUSVE University of Venice, Italy. He is President of the Italian Association of Criminology (AIC) and a member of the Board of Directors of the International Society of Criminology (ISC).