INTRODUCTION

A former al-Qaeda affiliate, the “Islamic State in Iraq and Syria” (ISIS) spread in various geographical areas and once controlled large territories in Syria and Iraq. Its rapid expansion surprised many terrorism experts and political leaders. With a daily income of millions of dollars and militants recruited from almost all parts of the world, it operated at a global scale as one of the deadliest terrorist organizations of our time.

The destruction in Syria and Iraq served ISIS’s needs in the region, as ISIS became one of the bombshells that followed the disappointments of Arab Spring. Even if it has been known since the first years of the Iraqi invasion of 2003, ISIS has fundamentally picked up the slack of al-Qaeda and has become one of the most predominant regional actors to benefit from the turmoil in Syria and Iraq (Elmas Reference Elmas2015).

Another unprecedented aspect of ISIS is its competent media communication strategy and the way it utilized social media and other media tools to facilitate propaganda and recruitment activities. Ranging from social media, video platforms and other tools on the Internet to professionally designed journals, magazines and particular propaganda videos, ISIS managed to transform itself into a highly adept propaganda machine (Elmas Reference Elmas2015). Through using media, it has been able to convey its violent extremist ideologies and destructive messages to populations beyond the borders of Iraq and Syria. Turkey is one of the countries that ISIS targeted in establishing a recruitment ground.

The success of the ISIS media campaign is evident in the number of foreign fighters that joined ISIS. According to one assessment, the number of foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq was between 27,000 and 31,000, and almost 5,000 of them were from the European Union countries (The Soufan Group 2015).

This article aims to focus on how ISIS utilized media in recruiting new members. To do that, the article concentrates on analytical findings of a research on Twitter messages posted by Turkish-speaking pro-ISIS accounts, and attempts to shed light on how ISIS’s global media communication strategy is reflected in cyberspace and social media in particular.

SOCIAL MEDIA AND TERRORISM

Media are the primary space where power is determined, having the widespread capability required to shape public opinion (Castells Reference Castells2007). Through exercising power to influence human minds, communication networks are easy ways to consolidate power (Castells Reference Castells2015). Among many other media tools, online communication instruments and the public cyberspace generated by these instruments are the foremost agents of construction for the identity of individuals, groups and institutions, and the like. Especially, social media platforms like Twitter, YouTube, Facebook and many others highly mediate this identity construction process and allow individuals to communicate without dependence on traditional organizational hierarchies.

Social media tools also help to create a new form of public space wherein people can interact without needing to share the same place or direct physical contact. This empowers “the individual” and provides broader anonymity compared with life in physically shared public space since people’s online identities are composed of textual descriptions and representations of “the self” (Waymer Reference Waymer2007:79).

Distinct from face-to-face interaction, communicating over social media in public cyberspace is less orchestrated and requires less behavioral synchronization. This is because in face-to-face interaction, all the gestures, body language, eye contact and physical appearance deliver silent signals to the other person. These signals are at the heart of the interaction and disclose one’s real intentions during interaction (Margalit Reference Margalit2014). However, interaction over social media lacks such features of face-to-face interaction, and while emotions can be transmitted and spread through texts, social media enable latent communication, or namely communication made under the guise of anonymity, in public cyberspace. Furthermore, social media also create cohesiveness and a sense of belonging to the group regardless of geographic location. In other words, social media mediate a vibrant and dynamic linkage between the individual and the group, and connect the individual to the group.

Terrorist groups are effective agents in public cyberspace and online propaganda is a common method that terrorist organizations like ISIS use to attract and recruit potential members. It allows militants to take advantage of the ease and the convenience brought about by the improvements in communication technologies and enables them to reach and motivate their sympathizers (Ozeren Reference Ozeren2009). People’s social milieu, their network of relationship along with factors like their ideology, identity and past experiences affect radicalization, but technology can play a role and sometimes instigate their transformation into radical agents (Archetti Reference Archetti2015).

ISIS MEDIA CAMPAIGN

ISIS has used different digital channels to engage its supporters and communicate its ideology to people around the world (Shamieh and Szenes Reference Shamieh and Szenes2015). The organization’s information operations have four distinguishing characteristics: the violent content of the messages, the slick production of visual materials, the volume of information operation output, and the role of social media in disseminating the information (Ingram Reference Ingram2015).

ISIS has an effective media unit that feeds its members and adversaries with an enormous amount of visual and textual information. The ISIS media architecture can be analyzed at three levels. The first level is the central media unit that typically passes major announcements to the provinces. ISIS’s official media channel, Al-Hayat Media, specifically targets non-Arabic-speaking audiences and distributes materials in several other languages, including Turkish. The second level is the wilayat (authoritative) information offices that produce informational materials about localized issues and events. The third level is ISIS members and supporters who disseminate official and unofficial material through social media (Ingram Reference Ingram2015). Because the production, translation and dissemination of those resources is perceived as a form of jihad, Al-Hayat Media productions reach millions of people with the help of volunteers from around the world via the Internet and social media (Berger and Morgan Reference Berger and Morgan2015).

One of the major goals of ISIS is the recruitment of foreign fighters. The organization’s global media campaign fulfills this goal through radicalization and identity formation. The media campaign is used to create a dual image – one that is both loved and hated at the same time. Violent videos of mass killings, executions and torture have been used as tools to frighten or provoke ISIS adversaries on the one hand and to recruit sympathizers from other parts of the world on the other. In addition, ISIS members use social and other types of media to post pictures showing the caliphate as an idealistic place for their sympathizers and to encourage them to hijra (migration for the sake of Allah) and migrate to areas controlled by ISIS. The number of foreign fighters joining ISIS each day proves the effectiveness of its media campaign (Peresin and Cervone Reference Peresin and Cervone2015).

The organization’s media messages are used exclusively to shape the perceptions of its target audiences and consolidate their support for the cause. ISIS has been successful in its efforts by addressing pragmatic and perceptual factors (see Figure 1). In terms of pragmatism, ISIS aims to shape people’s perceptions about the organization with an emphasis on a promise of stability, security and livelihood for its supporters. In terms of perception, however, ISIS emphasizes in-group and out-group identities to arouse its sympathizers and gain their support for the organization’s vision. ISIS messages generally appeal to pragmatic and perceptual factors simultaneously. Pragmatic factors, however, are more likely to influence local populations, while perceptual factors could have grater resonance with transnational audiences (Ingram Reference Ingram2015).

Figure 1 The strategic logic of Islamic State (IS) information operations (Ingram Reference Ingram2015)

The ISIS communication strategy also aims to motivate all Muslims to hijra for jihad and restoration of the caliphate as part of their religious duty. To persuade its audiences, ISIS portrays itself as “the true apostle of a sovereign faith, a champion of its own perverse notion of social justice, and a collection of avengers bent on settling accounts for the perceived suffering of others” (Farwell Reference Farwell2016:49–50).

METHODOLOGY

This study is guided by three interrelated research questions:

-

(1) How did ISIS utilize Twitter to disseminate its propaganda to the Turkish-speaking population?

-

(2) What kind of social media tactics did ISIS use to attract new recruits from Turkey?

-

(3) What were the specific patterns for Turkish-speaking ISIS sympathizers on Twitter?

To answer those questions, this study analyzes Turkish-speaking pro-ISIS Twitter accounts. These accounts were identified through several stages, using a variety of methods. First, a starting list of pro-ISIS Twitter users was generated by examining Twitter accounts of known ISIS news sites and their followers. Pro-ISIS users were identified by examining the avatars and cover photographs. The ISIS supporters are generally using ISIS-related figures, IS flags, Islamic symbols or war-related pictures such as fighters and weapons as avatars and cover photographs. Then the Twitter messages, posted or re-tweeted, were analyzed to determine if a specific account belonged to an active pro-ISIS user.

These accounts were followed for three months, and the tweets posted by these accounts were analyzed on a daily basis. Tweet data have been crawled through original REST API provided by Twitter Company. By using a special algorithm developed for this research, the initial list of accounts was expanded by analyzing the accounts following them and the accounts they were following. This algorithm also helped to analyze posted tweets and conduct lexical analysis of messages including the deleted ones. The identification period, the first stage, was followed by a three-month testing period. At this stage, selected accounts were checked to see whether those accounts were actually posting pro-ISIS messages. The testing period lasted from March to June 2015.

During this testing period, some of the accounts were suspended. However, owners of those accounts have usually created new accounts and announced them through other users, so those new accounts were also added to the list. Some particular accounts were found irrelevant or inactive and were dropped from the list. Several new ones, on the other hand, were discovered and added to our pool of seed accounts during the same testing period.

At the end, a total number of 290 Turkish-speaking pro-ISIS Twitter accounts were identified as the seed accounts and these accounts were followed for the data collection. The data collection started following the testing period on July 1 and ended on July 31, 2015. Then, the data analysis stage began.

The data used in this study pertain to 25,403 unique tweet messages publicly posted by 290 Turkish-speaking pro-ISIS Twitter accounts between July 1 and 31, 2015. The names of sampled accounts or any other information that may lead to the identification of the users are not disclosed for privacy reasons. Nicknames or alphanumeric codes are used when necessary.

ANALYSIS OF SOCIAL MEDIA DATA

The data have been analyzed in terms of their characteristics, including gender, account creation date, distribution of friends and followers of sampled accounts, tweeting patterns and popular hashtags.

Gender

Sampled Twitter accounts preferred both Turkish or Arabic usernames and screen names. Most of the names were associated with the ideology of ISIS, the religious words and terms that ISIS have been exploiting, historical figures, war/jihad-related terms, and ISIS- and Al-Qaeda-related words. Some users, on the other hand, used nicknames without any apparent association with the ideology of or any other symbols of ISIS. A similar pattern is visible in selection of profile images. Most accounts picked ISIS symbols like the ISIS flag, war/jihad-related images, religious symbols or verses from the Quran, historical figures or ISIS leaders.

While it is not possible to accurately identify these accounts’ gender, usernames, screen names, avatars and cover images provide useful clues to make a prediction. Some accounts preferred Muslim female names like Meryem, Sumeyye or Merve as their usernames or screen names. Some accounts used pictures, depicting a woman wearing hijab. Those pictures were generally taken from the side or behind, or the persons fully covered their faces with a veil, so that their faces were not visible in the photographs.

If a user chose a female picture showing even a portion of the face, like the eyes, that user was warned by other pro-ISIS Twitter accounts and requested to change it with a proper one. As a result of this informal internal control, some accounts were using baby, flower or butterfly pictures in their accounts. In addition, some accounts used colors like pink and violet, or twinkle backgrounds. Most importantly, message contents also provided us with important clues about the gender because female users post more on women’s issues.

Based on these clues, it is estimated that 44 of 290 seed accounts were of female users (Figure 2). This also reflects the fact that the majority of those who join ISIS are males. However, it should be noted again that these numbers are just estimates. There may be female users appearing as male or male users appearing as female, so it is not possible to identify the gender of a Twitter account with 100% accuracy.

Figure 2 Account owners’ gender

Account Creation Date

The annual account data show that there was a considerable increase in the number of Twitter accounts created in the years of 2014 and 2015 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Distribution of seed accounts by year

Also, 174 of 290 accounts were created in 2015 and 71 of them were created in 2014. This is equivalent to 84.5% of all seed accounts. The remaining 44 accounts were created between 2010 and 2013, which equals about 15.5% of the group. Only one seed account was created in 2009.

This is not a surprise given the rise of ISIS in Iraq and Syria in 2014. Accordingly, ISIS became popular in Turkish news during the same period, and it has consequently begun to be more well known among the Turkish populace. In other words, ISIS started to target Turkey as a recruitment ground, and one of the ways of enlisting communication with the targeted audience was the use of Twitter. The increase in the number of pro-ISIS Twitter accounts also coincided with the increase in the number of ISIS-related recruitment activities in Turkey.

The year 2015 is noteworthy, since the number of new accounts almost tripled in comparison with the previous year (see Figure 4). The monthly mean of account creation is 24.9, and there is a sharp increase in March that continues through July.

Figure 4 Distribution of seed accounts opened in 2015

It is important to note that ISIS was an important topic in Turkish media during February and March of 2015. On February 22, 2015, the Turkish Armed Forces entered Syria and evacuated the tomb of Suleyman Shah. It was argued that the shrine had been under siege by ISIS fighters since March 2014. The operation has been criticized by the opposition groups in Turkey on the ground that Suleyman Shah’s tomb was the only piece of Turkish soil outside of Turkey’s borders. ISIS supporters have presented this event as a show of strength and its level of influence in international affairs, claiming that even nation states were unwilling to confront them directly.

On March 1, Turkish security forces launched a crackdown on ISIS networks in several cities in Turkey. Another noteworthy development was that Turkey and the United States had an agreement to deploy armed drones to Incirlik airbase to use against ISIS targets. Those developments indicated a policy change towards ISIS and that might be reflected in the volume of the activities in social media use.

Friends and Followers

Friend and follower figures are important to understand the level of influence of any given Twitter account. For the sampled seed accounts, the mean number of friends is 587.7, while the mean number of followers is 990. Figure 5 and Figure 6 indicate the frequency distribution of friend and follower counts.

Figure 5 Frequency distribution of number of friends

Figure 6 Frequency distribution of number of followers

According to these figures, pro-ISIS Twitter accounts have more followers than friends. However, it is important to note that these numbers can be manipulated by using bots and third-party spam services that sell followers.

The distribution of friend figures shows that 28.3% have fewer than 100 friends, 47.6% have 100–499 friends, 12.4% have 500–999 friends and only 11.7% have more than 1,000 friends. On the other hand, the distribution of follower counts shows that 11.7% have fewer than 100 followers, 45.9% have 100–499 followers, 24.1% have 500–999 followers, 16.9% have 100–9,999 followers and just 1.4% have more than 10,000 followers.

The follower/following ratio is a handy indicator of a user’s influence on Twitter. The mean follower/following ratio is 63, which shows that most of the accounts have far more followers than friends. In fact, of 290 seed accounts, about 67% have a friend/follower ratio greater than 1. Of the accounts, 14 have a follower/following ratio greater than 100, which indicates that those accounts are popular information sources and do not follow others.

Tweeting Patterns

Within the research period, a total of 25,403 tweet messages had been posted, and 17,948 messages had been deleted by sampled pro-ISIS accounts. The average number of posted tweets per day was 819, and the average number of deleted tweets was 579.

Figure 7 shows the daily number of tweets posted and deleted by pro-ISIS accounts. However, it is important to remember what ISIS activities took place in July in Turkey in order to better interpret the sharp increase and decreases in the chart:

-

∙ Turkish security forces began a series of operations to dismantle ISIS recruitment networks in Manisa on July 7, 2015. Operations spread to big cities, including Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir, by July 12, and continued throughout the month.

-

∙ On July 20, a suicide bomber killed himself and 33 Turkish citizens in Suruc. Suruc is a small district of Sanliurfa and is very close to the ethnically Kurdish Syrian border city of Kobane, where fierce clashes between the Kurdish YPG (Yekîneyên Parastina Gel or The People’s Protection Units) and ISIS have occurred. Victims were en route to visiting Kobane to show their support for the Kurdish residents of the city.

-

∙ On July 22, two police officers were killed by the PKK (Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê or Kurdistan Workers’ Party) while they were sleeping in their apartment.

-

∙ On July 23, one Turkish soldier was killed and several others injured by terrorists who carried out the attack from an ISIS-controlled area in Syria.

-

∙ On July 24, Turkish fighter jets struck ISIS targets in Syria.

Figure 7 Distribution of posted and deleted tweets in July 2015

The average number of posted tweets was 889 between July 1 and July 11. It began to fall after ISIS operations in Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir on July 12, and remained low until July 20. The mean was 604. Afterwards, it appears that pro-ISIS accounts had launched a social media campaign, as the daily number of tweets began to rise again between July 20 and July 24. The mean was 985. It again fell down after July 24 after military operations against ISIS targets in Syria. Except for a sharp increase on July 30, it remained at a mean of 702.

Message deleting also has a similar pattern. The mean of deleted tweets was 305 between July 1 and July 12, but the number of deleted posts rose to 2,425 on July 13 after police operations. Then, it fell down again, but was still higher than in the first days of July, with a mean of 424 tweets between July 14 and July 22. On July 23, deleted tweets rose again to 2,246 and subsequently the mean of deleted tweets was 894 until the end of the month. This shows that pro-ISIS accounts are very responsive to ISIS-related developments in Turkey. Pro-ISIS supporters fear that their real identities can be revealed and they can face legal charges for their online activities.

Popular Hashtags

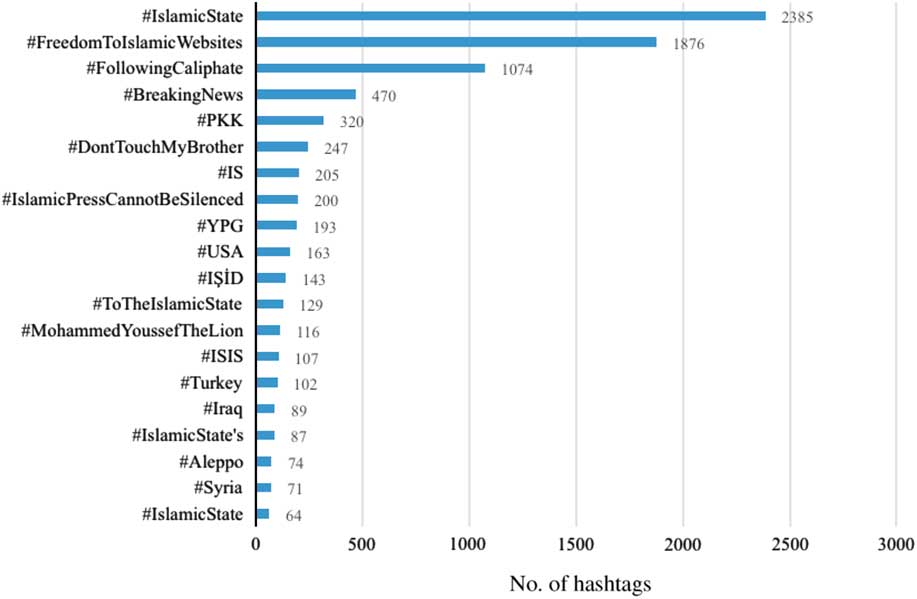

Since the purpose of Twitter hashtags is to emphasize messages and make them more publicly available, hashtags created by seed accounts give important clues about their agendas (see Figure 8). According to data analysis, the five most popular posted hashtags are as follows:

-

∙ #IslamicState (#İslamDevleti)

-

∙ #FreedomToIslamicWebsites (#İslamiSitelereÖzgürlük)

-

∙ #FollowingCaliphate (#HilafetTakip)

-

∙ #BreakingNews (#SonDakika)

-

∙ #PKK

Figure 8 The most popular hashtags. PKK, Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê (Kurdistan Workers’ Party); IS, Islamic State; YPG, Yekîneyên Parastina Gel; IŞİD, Irak Şam İslam Devleti; ISIS, Islamic State in Iraq and Syria

Terrorist organizations aim to construct a sense of belonging and identity among their sympathizers. One of the ways to accomplish this is to use names – those of the organizations, those of their leaders, etc. – as symbols in order to cultivate a feeling of group membership among their likely supporters. This is an important issue in ISIS’s case, especially for those who previously have no connection or affiliation with the organization. Using different forms of the organization’s name enables followers to get accustomed to the name of the organization which eventually will create a kind of group dynamic among the followers. Therefore, it is quite expected to see #IslamicState (#İslamDevleti) as the leading hashtag. Together with other hashtags with similar meaning such as #IS, #ISIS and #IŞİD, it is mentioned by 2,838 times in total.

The second most popular hashtag was #FreedomToIslamicWebsites (#İslamiSitelereÖzgürlük). Together with the #IslamicPressCannotBeSilenced (#İslamiBasınSusturulamaz) hashtag, it is mentioned 2,076 times. As mentioned above, in July 2015, Turkish security forces launched a crackdown on ISIS recruitment networks and blocked pro-ISIS websites as a part of that operation. It seems that ISIS supporters initiated a social media campaign to protest that decision.

The popularity of this hashtag also reflects how pro-ISIS Twitter accounts are worried about restrictions to their digital media campaign in Turkey. Such reaction shows that cyberspace could be an effective arena for countering violent extremism. Accordingly, in order to effectively counter ISIS, cyberspace should be one of the primary areas of focus for policy makers.

It is also revealed that sampled accounts are also being used to follow the latest events and updates about ISIS through certain hashtags such as #FollowingCaliphate (#HilafetTakip) and #BreakingNews (#SonDakika). In July 2015, 1,544 total messages were posted with those hashtags. This shows that following the latest updates about ISIS is quite popular among sampled accounts and it composes the third most frequently mentioned topic of the hashtag data.

The popularity of hashtags #PKK and #YPG indicates the fact that ISIS uses its rivals in Syria, which are the PKK and the YPG, to mobilize its supporters. In fact, as previously mentioned, the clashes between the PYD (Partiya Yekîtiya Demokrat), PYD’s military wing YPG and ISIS have been reflected in Twitter messages. In those messages, ISIS presents the YPG as the common enemy of both ISIS and Turkey. Even though the “Republic of Turkey” is portrayed as kafir (infidel) in tweets posted by ISIS, the account owners express blatant support for Turkish security forces when discussing YPG. ISIS’s strategy to feed into existing animosities between different groups can be observed in this case. ISIS tries to take advantage of possible tensions in the country.

In fact, this strategy is also demonstrated not just in social media, but in ISIS’s self-proclaimed battleground. The attacks in Diyarbakir, Suruc and Ankara targeted mostly Kurdish people and those with left-wing ideologies, seeming as if they were making war against the PKK. But, in reality, when ISIS carries out any attack, it is essentially targeting the peace and stability of any given country.

Some of the hashtags include the names of ISIS militants who were killed in clashes or who killed themselves in suicide attacks such as #MohammedYoussefeLion (#AslanParçasıMuhammedYusuf) and #OperationCalledMartyrYalcin (#OperasyonunAdıŞehitYalçın). Using these names enables ISIS to present real-life examples for potential recruits. They portray these people as “martyrs to ISIS’s cause”. For instance, Mohammed Youssef Abdulazeez is the name of the person who attacked military installations in the United States and killed four soldiers. By using his name as a hashtag, ISIS or ISIS sympathizers aim both to announce their so-called “operations” and to mobilize new recruits to provide belongingness to ISIS.

ANALYSIS OF FEMALE SOCIAL MEDIA USERS’ POSTS

A total of 2,472 messages were posted on social media in July 2015 by users identified as females. Female users are identified by looking at user names, screen names, avatars and cover images used with the accounts. The contents of each message were reviewed to verify the researchers’ estimation about gender. All of the messages were examined and coded carefully.

Initial coding showed that most of the posts contained messages related to breaking news, ISIS social media campaigns, verses from the Quran and other religious sources that ISIS exploited, or conversations with other users. As a result, 619 messages were used for this study. Table 1 shows the top five most-discussed topics and the number of messages sent about each topic.

Table 1 Top-Five User-Posted Topics

PKK, Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê (Kurdistan Workers’ Party).

Not surprisingly, jihad is at the top of the list. Like their male counterparts, female ISIS supporters view jihad as the most important duty of Islam. They repeat the arguments that the Islamic world has been humiliated by Western countries, that Islamic countries are actually governed by Western powers, and that all Muslims have to stand against such countries.

In one message, for example, the user states, “If you don’t say anything while the Ummah [the entire community of Muslims bound together by ties of religion] is being humiliated, please at least don’t be against us.” The argument that women and girls are victims of rape was used many times in messages to instigate Muslim men. In one such message, Muslim men were the focus: “Men of ummah!... With which honor are you sitting quietly while your sisters are being raped. Shame on you. At least don’t defame jihadis.” Similar content is echoed in the following message: “You would know what Al-Qaida is if your wives and daughters were raped too.” The women argue that ISIS and other jihadists all over the world fight to stop the humiliation of Islam by shedding their blood.

Furthermore, according to ISIS supporters, it is a religious duty for every Muslim man and woman to join the jihad. Many messages expressed the women’s desire to join the jihad and become a martyr: “Jihadi life is better than slavery.” “Let me fight and die for God at a battleground.” “My body wants to get shattered towards paradise.” “An unpinned jihadi can only get calm at paradise.” In one message, a woman complains about not being admitted to a university and says that she would attend “Idlib university, jihad faculty, kalashnikov department.” The women also want husbands who seek martyrdom. One of the users writes, “It is especially different if you have a lover who fell in love with martyrdom.”

Another common topic is hijra. Pro-ISIS Twitter accounts depict hijra as an ideal act of ISIS sympathizers, with tweets encouraging Muslim women to emigrate to ISIS territories. Typical messages include the following: “We are going to the caliphate… We are going to victory… God will give us conquests.” “Mom, life is beautiful in the caliphate, death is beautiful with martyrdom,” “Beware of dying at kufr [denial, rejection, turning away in arrogance, hypocrisy, doubt] land.” “Hold my hand, let’s go to jihad.” Similar messages show female ISIS supporters’ eagerness to leave their families behind for hijra and live in ISIS-controlled territories.

Other messages caution young girls not to believe men who try to persuade them over the Internet to migrate to ISIS for marriage. The messages posted warn the girls that if they want to marry a jihadist husband, they should talk with people they know who worship at a mosque or are a member of an organization associated with ISIS. The posters note that many Syrian women left their families for ISIS and married jihadi men but add that life might become harder for them if their husbands are killed in combat. If they became pregnant or gave birth to a child, the posters continued, it could be harder for them to return to their families. These accounts also criticize jihadists who try to lure young girls into Syria. The posters claim that if members of ISIS in Syria and Iraq want to get married, there were many widows of martyrs now living in poverty. They argue that young girls who run away from their homes to join ISIS put ISIS supporters in a difficult position and cause anger to be directed toward them in Turkey.

In several other messages, the women complained about men and women who were looking for a romantic relationship under the guise of jihad. One such message contained this complaint: “Flirt is named as jihad. Hold my hand, let’s go to jihad. Is jihad a place for committing sin?” Several messages expressed similar criticism: “Help youngsters for God’s sake. As we couldn’t become accustomed to romantic Islamists yet, now there are romantic jihadist.” The women also criticized male users who post their picture as an avatar. For example, one woman wrote, “A woman who uses her veiled picture as avatar is fitnah [unrest], but man who use his own is not, right?” They also argue that Turkish women’s religious dresses are not suitable for Islamic requirements.

The PKK is another topic of pro-ISIS social media messaging. As stated before, on July 20, a suicide bomber exploded himself in Suruc, Turkey, and killed 33 Turkish citizens who were en route to Kobane, Syria, to show their support for the Kurdish YPG (People’s Protection Units). After the incident, messages on pro-ISIS social media accounts claimed that PKK supporters were attacking Muslims in different cities in Turkey and urged all “brothers and sisters…to be extremely careful.”

Finally, female social media users frequently made violent remarks in their messages about the PKK, Turkey, the West or what ISIS call infidels in general. Examples include: “If you are infidel, we cut off your head with care.” “If my infidel dad harms my brother, I cut his throat.” “The only language that infidels understand is a sword on their neck.” These messages show the extent to which the women can justify violent acts targeting others.

Cyberspace is one of the areas where ISIS is very active. Through a highly competent media communication strategy, the organization tries not only to disseminate propaganda and recruit new members but also to provide a sense of belonging to a group with a self-proclaimed just cause and to strengthen existing bonds among its sympathizers – especially those in Western countries. The ISIS social media strategy is to create cohesiveness and a sense of belonging for its members, opening avenues for ISIS sympathizers to keep in contact regardless of geographic location. ISIS therefore gives special importance to propaganda activities and maintains its social media presence with striking professionalism.

SUMMARY

This study focused on social media and terrorism by analyzing how pro-ISIS Twitter users see and legitimize ISIS and its ideology in Turkish cyberspace. The analysis showed that ISIS has tried to gain sympathy and strengthen its base among Turkish citizens. In its efforts to do so, ISIS actively uses social media tools consistent with its global media strategy. For example, 25,403 tweets were posted in one month from only a small sample of ISIS supporters. The daily number of tweets posted and deleted shows that pro-ISIS users are highly sensitive to international and domestic events.

An examination of the tweets showed that pro-ISIS accounts have been interpreting global incidents according to ISIS ideology and that two interrelated concepts are at the epicenter of this interpretation: hijra and jihad. Pro-ISIS Twitter accounts are urging all Muslims to migrate to ISIS-controlled territory and become involve in jihad against the enemies of Islam. The tweets present hijra as a religious duty by arguing that ISIS is the only Islamic state where Muslims can live according to Islamic law. The tweets also argue that Islam is under attack and that jihad is the most important religious duty for every man and woman. The concepts of hijra and jihad, therefore, appear frequently in pro-ISIS users’ Twitter messages and are used to recruit new members.

The ability of ISIS to use both social media and traditional methods of recruitment requires countries around the world to adopt multifaceted approaches for eradicate the organization. To this end, social media (and cyberspace in general) are critical to understanding how ISIS sustains its recruitment and propaganda activities.

Acknowledgements

Data for this study came from the GLOBAL Policy and Strategy Institute, an independent think tank based in Ankara, Turkey, that conducts scholarly research and analysis.

Suleyman Ozeren is an adjunct faculty at the Department of Criminology, Law and Society and a research scholar at the Center for Global Policy at George Mason University. He formerly served as the President of the Global Policy and Strategy Institute and as the Director of the International Center for Terrorism and Transnational Crime (UTSAM) in Turkey. His research interests include terrorism and counterterrorism, radicalization, countering violent extremism, international security, emerging transnational threats, conflict resolution and the Kurdish issue. In his research, he examined four terrorist organizations: ISIS, Al Qaeda, Hezbollah and the Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK). Dr Ozeren has taught numerous graduate and undergraduate courses on terrorism, comparative counterterrorism strategies, intelligence and conflict resolution at four different universities.

Hakan Hekim is studying public policy and is interested in policy analysis, cyber crimes, digital forensics and science and technology policies. He taught criminology, information technology, cyber crimes and computer forensics courses at different universities in Turkey. Hakan has a master’s degree in Information Science and a Ph.D. in Public Policy.

M. Salih Elmas is a researcher in international security. He has B.A. in Sociology, M.A. in Crime Studies and Ph.D. in International Security. His research primarily focuses on terrorism, the radicalization process and current security threats threatening the Western world such as ISIS and Al Qaeda. He is one of the co-authors of the latest report titled “ISIS in Cyberspace: Findings from Social Media Research”. Dr Elmas has worked in some university-affiliated and non-governmental organizations as a researcher and academician and participated in several national and international projects on countering violent extremism, terrorism, migration and migrant smuggling. He has several publications and published op-eds on ISIS and its illusion, terrorism and security dynamics of modern societies. He is also the author of the book titled The Security Impasse in Modern Society published in Turkish.

Halil Ibrahim Canbegi was a researcher in the GLOBAL Policy and Strategy Institute’s Center for Regional Studies in Turkey. He is a Ph.D. candidate at the Middle East Technical University. His research interests include Middle East politics, conflict resolution studies, comparative politics, terrorism and radicalization.