Capital controls have often been used to mitigate the impact of past financial crises and will likely be called upon in response to any financial crises precipitated by the COVID-19 global health pandemic. The consequential economic fallout from COVID-19 will be larger than that of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008 and possibly approach that of the Great Depression of the 1930s.Footnote 1 Life afterwards will not return to the pre-crisis normal. There will be wide-ranging and historically significant global and behavioural changes,Footnote 2 and one of the more likely of these is a retreat from globalisation.

Before the pandemic there was vigorous scholarly debate as to whether globalisation was subject to the control of nation States or simply a phenomenon to which nations had to adapt. This debate may have ended as citizens around the world have turned to their States to protect them, and the resurgent power of nations to act, powerfully and decisively, is manifest everywhere.Footnote 3

The most globalised sector in most national economies is finance. Interest rate changes in the United States (US) or United Kingdom (UK) regularly affect the rates paid by borrowers in countries throughout the world. Capital moves more rapidly and extensively around the planet than almost anything else.Footnote 4 Any substantial retreat from financial globalisation will involve controls on those capital movements and at least a partial return to the economic orthodoxy of the 1950s and 1960s, when national economies were separated by strong controls which rigorously regulated and curtailed the flow of capital.

By the 1990s, the orthodoxy of the 1960s had become heresy. The interests of the world's major banks and financial institutions had prevailed in the contest of ideas around the free, unfettered movement of capital. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) was fundamentally opposed to capital controls and international treaties, other agreements and rules were developed that sought to limit or prohibit such controls. Although acceptance of such controls began to increase from 2000 onwards, they remain a controversial policy measure, even during periods of crisis.Footnote 5 Concerns remain, for instance, that such controls will worsen the global liquidity crunch, further interrupt international investment, trade, and supply chains, and jeopardise post-crisis recovery.Footnote 6 Nevertheless, recent evidence suggests that capital controls are an important part of the policy tool kit, especially during crises,Footnote 7 and particularly for developing and emerging economies which, during crises, typically suffer from surges of capital outflows, and severe declines in currency and asset prices.Footnote 8

This article explores what will be involved for nations that wish to restore capital controls to their suite of policy options and use them to insulate their economies from financial globalisation. So extensive and wide-ranging have the web of treaty obligations and rules of international organisations become, this retreat from globalisation will not be a simple process, at least for nations that wish to abide by their legal commitments and respect the rule of law.

Capital controls encompass a wide range of (often country-specific) measures. Restrictions on capital flows have, in general, taken the form of administrative or direct controls (including outright prohibitions and approval procedures) and market-based or indirect controls that attempt to discourage capital movements by making them more costly (like a Tobin Tax or unremunerated reserve requirement). The controls may be sector-specific or economy-wide and may be short-term or long-term measures.

The economic literature is replete with studies on the role of capital controls and foreign exchange. In the early years of the Bretton Woods era, the 1950s and 1960s, such controls were routine and widespread, especially in advanced economies. With fresh memories of the Great Depression of the 1930s, White and Keynes (of the US and UK) and the other architects of Bretton Woods envisaged nations as financial islands between which the movement of capital would be controlled by national governments. What mattered in the 1940s was trade, much more than finance. This is reflected in the original draft of the IMF Articles of Agreement which envisaged capital controls as a permanent, structural element of international finance.Footnote 9 Accordingly, in the 1950s and 1960s capital controls were economic orthodoxy. However, as finance became increasingly prominent in the global economy, the interests of the US, Europe and their banks were supported by the free movement of capital globally. The situation was otherwise in emerging markets where capital flow restrictions were adopted to promote inward-looking models of industrialisation until the 1980s, when even these economies began to liberalise their capital accounts.Footnote 10

Over time, what had been developed world orthodoxy became progressively more heterodox, as the IMF and US Treasury began to advocate strongly against capital controls. This advocacy began in the 1970s and proceeded apace in the 1980s and 1990s. Mainstream economics saw capital account liberalisation as the best long run policy for all countries and regarded controls on capital flows as inherently distorting.

In the aftermath of the GFC of 2008, mainstream economics underwent a significant shift in thinking. Capital controls began to be appreciated once again for their ability to restrain significant surges and interruptions in cross-border capital flows in times of financial crisis, and the regulation of capital flows began to be seen as acceptable, and perhaps even necessary, to prevent financial fragility and maintain monetary policy autonomy especially in developing nations. For its part, in 2012, the IMF adopted an ‘institutional view’ on capital account liberalisation and capital controls which explicitly acknowledged that controls on inflows and outflows can be appropriately utilised in certain circumstances to prevent and mitigate financial instability.Footnote 11 The IMF's shifting stance on capital controls has received much attention, and provided comfort to countries seeking to limit exposure to global capital markets and unfettered capital flows and the volatility these tend to bring.

This is not to say that the debate among economists on the usefulness and effectiveness of capital controls is resolved, but only that as a practical matter capital controls have ‘come in from the cold’, and are now seen as having some legitimacy.

The view through the lens of international economic law, however, is far less clear. In short, there is no simple legal answer on whether a country can impose or maintain such controls. The answer depends on the legal frameworks each country has entered into—these include the World Trade Organization's (WTO) General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), free trade agreements (FTAs) and bilateral investment treaties (BITs).

This article analyses whether and to what extent capital controls can be justified under the general principles and norms of international economic law by evaluating measures imposed by four representative countries. Our analysis will demonstrate the importance of treaty language in determining the consistency of a capital control with a nation's international legal obligations.

This article is structured as follows: Section I uses a case study approach to examine country level experiences with the use of capital controls. The section explores the use of capital controls in regulating volatile short-term and long-term capital flows. Section II focuses on the legality of controls. The use of controls is not governed by a single international law regime. In fact, there is no comprehensive legal edifice that defines when capital movements should be restricted or controls removed. Instead, controls are regulated by an intersecting web of monetary, trade and investment law. More specifically, Section II details the fragmentation of international disciplines on capital controls and offers select examples to evaluate whether a given control measure is consistent with the language of international treaties. Section III concludes that it is difficult to reach a definitive conclusion on whether specific actions are consistent with the international legal framework given the patchwork of varying agreements with differing treaty language and levels of commitments. The actions of one country could be consistent with its obligations under some of its treaties and inconsistent with others.

I. Capital Controls: Country Experiences

Before evaluating the consistency of capital controls with international economic law it is necessary to trace their evolution over time. Short-term controls have been fairly regularly used by several countries to address financial instability—most prominently to counter the effects of an overabundance of capital inflows that cannot be resolved by conventional policies. Longer-term and more extensive controls are rarer, and most often feature in countries that have historically been closed and heavily State-controlled to limit the vulnerability of their financial systems.

In this section, we review short-term and long-term controls on both inflows and outflows. We begin by considering Chile's short-term inflow and outflow controls, and Malaysia's short-term outflow controls, imposed in the late 1980s and 1990s. We then consider the longer-term outflow controls imposed by Iceland in the wake of the GFC, and conclude with a case study of China's long-standing capital controls imposed ever since its opening up in the late 1970s.

A. The Case of Chile

The Latin American debt crisis of 1982,Footnote 12 resulted in massive disruption and near collapse of the Chilean economy—GDP fell by 15 per cent and the country was plunged into severe economic turmoil in 1983.Footnote 13 Chile recovered fairly quickly and foreign capital started to flow in increasing amounts by the late 1980s. While the rest of Latin America remained enmired in the debt crisis, major policy and institutional reforms meant that debt restructuring would not be required for Chile.Footnote 14 In short, the Chilean economy was stronger than that of its neighbours and thus became attractive to foreign investors.

The damage caused by the sudden cessation of capital inflows in 1982 remained fresh in the mind when Chile's capital account surplus reached ten per cent of its GDP in 1990. To exacerbate the potential for instability, short-term flows represented one-third of this amount.Footnote 15 Fearing a repeat of 1982, Chile introduced capital inflow controls in 1991.

The capital controls Chile put into place had five elements:Footnote 16

1. All foreign loans and bond issues were subject to the requirement that an amount equal to a set proportion of the flow had to be put on interest-free deposit with the Central Bank for one year irrespective of the duration of the capital inflow. The proportion was initially set at 20 per cent. In response to the large exogenous surges of capital flows to Chile, the government frequently tightened controls on capital inflows. The coverage of the unremunerated reserve requirement (URR) was extended to other portfolio inflows and some foreign direct investments (FDI) of a potential speculative nature over time. In May 1992 it was increased to 30 per cent, and then in June 1996 reduced to 10 per cent. In 1998, the measure was suspended by reducing the rate to zero per cent.

2. Credit lines for trade finance were subject to the same reserve requirements.

3. Bonds issued abroad by local companies had to have an average minimum maturity of four years.

4. Shares issuance abroad by local companies was limited to companies with relatively high credit ratings and to amounts of not less than US$10 million.

5. Initial investment capital (but not profits) in FDI could not be repatriated for one year.

The first four restrictions are inflow controls, while the last is an outflow control. Most international attention has focused on the first restriction, the URR, an indirect market-based control which increased the cost of capital inflows. It was expected to discourage short-term inflows without affecting long-term foreign investment. The introduction of the second restriction, on trade finance credit, is on its face a barrier to Chile's international trade but necessary to close the loopholes for inflows through exempted windows, as otherwise the first restriction on debt and portfolio flows would be too readily circumvented, in the disguise of trade credits.

The general consensus is that Chile's controls lengthened the average maturity of capital it received.Footnote 17 There is strong evidence that the ratio of short-term debt to foreign currency reserves is a powerful predictor of financial crises, and that higher short-term debt levels are associated with more severe crises.Footnote 18 Short-term financing is simply not suitable, in the main, for developing countries. There is accordingly a strong argument for capital controls along Chilean lines that fall most heavily on short-term inflows.Footnote 19

Views are more divided over whether Chile's controls reduced the volume of capital inflows.Footnote 20 Certainly there was a strong initial effect: the capital account surplus fell from ten per cent of GDP in 1990 to 2.4 per cent in 1991 and short-term debt inflows were virtually eliminated.Footnote 21 When capital inflows surged again in 1992, the proportion of the non-remunerated reserve requirement was increased, again successfully.Footnote 22 Eventually, the controls lifted altogether, in 1998, when, in the aftermath of the Asian financial crisis global capital flows to emerging markets nations declined precipitately and there was no longer a need to discourage capital inflows and shift inflows towards longer maturities.Footnote 23

The controls increased the cost of credit within Chile considerably, particularly for small and medium-sized businesses that found their evasion most difficult.Footnote 24 This was a substantial price to pay. Nonetheless, Chile's controls altered the mix of incoming foreign capital in favour of long-term debt and away from instability-inducing short-term debt, and rapidly reduced increasing levels of inflows in 1991 and again in 1992.Footnote 25

In conclusion, for as long as a developing nation has a thin financial market, unsophisticated private sector risk management techniques and an unsophisticated and under-resourced capital market regulator, there are good arguments for controls, that are enforced strategically from time to time, on capital inflows.Footnote 26 This is particularly so in Asia, where high local savings rates diminish significantly the need for completely open capital markets. As an economy's own capital markets deepen, and its regulatory systems mature, it can safely liberalise its capital account. Many poorer developing nations are years away from this position.

In the interim, of course, the admonition against ‘free lunches’ generally holds. Capital controls have costs. Controls restrict access to foreign capital for investment and increase real interest rates.Footnote 27 Additionally, capital controls require considerable administration, and just as with trade barriers, can reduce the pressure for, and thus delay, needed policy adjustments and domestic reform.Footnote 28 To promote economic growth and stability, developing nations must continue policy reform and the development of efficient regulatory institutions even when controls are implemented.

As Chile's experience suggests, inflow controls can play a real role in stabilising an economy during periods of increasing capital inflows. Controls are a policy option that developing nations should be ready to implement, but only when needed.

B. Malaysia's Experience in the Asian Economic Crisis

Malaysia is an open economy with a long-standing commitment to relatively liberalised foreign trade. Malaysia removed restrictions on payments and transfers for current international transactions, accepting the obligations of the IMF's Article VIII as early as the 1960s, and subsequently liberalised its capital account. Malaysia's policy regime concerning capital flows was much more liberal throughout the post-war period compared to most other developing countries.Footnote 29 By the mid-1990s, Malaysia was a popular destination for volatile capital, its portfolio flows were generally free of restrictions, and it was in the midst of booms in equity prices and credit.Footnote 30

Following the 1997 crisis in Thailand, Malaysia at first implemented an orthodox adjustment policy and raised interest rates to stem the decline of the currency (the ringgit). Many referred to this initial response as an IMF package without the IMF.Footnote 31 At the time, and in consultation with the IMF,Footnote 32 Finance Minister Anwar Ibrahim tightened fiscal policy and made sharp spending cuts.Footnote 33 The resulting measures increased interest rates but also led to a pessimistic outlook for the economy which resulted in decreased consumption and investment demand.

This policy was subsequently altered on an ad hoc basis until July 1998 when Prime Minister Mahathir introduced the National Economic Recovery Program.Footnote 34 This decisive departure from IMF orthodoxy involved increasing government spending to stimulate the economy, capital controls to allow the government more control over Malaysia's economy and to prevent the outflow of foreign capital, and a restructuring package for the financial sector.

Malaysia was the only severely affected crisis country not to adopt an IMF program during the Asian financial crisis.Footnote 35 Given its relatively low foreign debt exposure, Malaysia took a heterodox path and departed from the IMF-centred approach.Footnote 36 Despite the intense debate on capital controls as a tool of crisis solution, with the benefit of hindsight, Malaysia's choice played a special role in delivering a recovery outcome and achieved political autonomy from international financial markets. Malaysia's policies saw it recover at least as fast as countries that implemented IMF policies and the poor in Malaysia were left significantly better off than they would have been under IMF policies. Malaysia also benefited in several other ways from charting its own course.

Malaysia took a multipronged approach to economic recovery. For instance, Malaysia reduced numbers of non-performing loans being carried by financial institutions, recapitalised these institutions and strengthened the system by closing and merging banks.Footnote 37 Like other crisis countries it also implemented ‘a blanket deposit guarantee and liquidity support’.Footnote 38

Malaysia's two unique responses were the introduction of capital outflow controls and the pegging of the ringgit to the US dollar.Footnote 39 The main controls on capital outflows were:

• Malaysia closed all channels for taking speculative positions against the ringgit and blocked all avenues for the transfer of the ringgit outside Malaysia. Residents were prohibited from granting or receiving ringgit credit vis-à-vis non-residents; all imports and exports were required to be settled in foreign exchange; all purchases and sales of ringgit financial assets can only be transacted through authorized depository institutions.

• Investors were required to repatriate all ringgit held offshore back to Malaysia, licensed offshore banks were prohibited from trading in ringgit assets, and approval requirement was imposed to transfer funds between external accounts.

• The authorities stopped non-residents removing portfolio proceeds from Malaysia for 12 months (excluding repatriation of interest, dividends, fees, commissions from portfolio investment). After six months passed, the 12-month restriction was replaced with a variable exit levy applying to principal or profit from investments in Malaysian securities. The exit levy excluded dividends, interests earned, and proceeds related to current international transactions and FDI.Footnote 40

• Additional measures were also imposed to eliminate the potential loopholes, such as prohibiting the trading of ringgit assets offshore, and limiting dividend payments to support the controls.Footnote 41

• The ringgit was pegged to the US dollar to prevent speculation in the ringgit.Footnote 42

Whilst such controls can be circumvented in various ways (notably through the settlement of commercial transactions, dividend payments, intra-firm transfers and mis-invoicing) circumvention was limited by Malaysia's design and enforcement of the controls.Footnote 43 The controls were designed to affect all channels for the movement of the ringgit offshore, whilst allowing current account transactions and FDI.Footnote 44 This selectivity minimised circumvention by leaving open certain options for investment in Malaysia through channels the government did not consider problematic from the perspective of capital flows.

Malaysia's performance during and after the crisis was better than most affected countries. Malaysia's rate of recovery was second only to the Republic of Korea in 1999 and Malaysia's negative rate of growth in 1998 was significantly less than Indonesia and Thailand, and not much more than Korea.Footnote 45 The most comparable crisis country, considering its level of development and the maturity of its system, was Thailand,Footnote 46 and Malaysia recovered slightly more quickly.Footnote 47 Merrill Lynch described Malaysia's recovery as ‘one of the most impressive ever’.Footnote 48 Kaplan and Rodrik wrote that ‘compared to IMF programs, we find that the Malaysian policies provided faster economic recovery … smaller declines in employment and real wages, and more rapid turn around in the stock market’.Footnote 49 And in late 1999 the Economic Strategic Institute noted that ‘despite the bad press it gets as a result of Prime Minister Mahathir's critical comments about speculators, Malaysia is the best story in the region’.Footnote 50

Early reactions to Malaysia's capital controls were more negative if not hostile. The policies were condemned as ‘a step backwards’ by the IMF and most academic economists.Footnote 51 The recovery did not necessarily imply causation and it was hard to attribute much success to capital controls because other crisis-hit countries, such as Korea and Thailand, recovered around the same time without using capital controls. The controls were criticised for not only weakening investors’ confidence but also cutting off much-needed foreign capital inflows, a pivotal element of Malaysia's pre-crisis economy.Footnote 52

Nevertheless, preliminary evidence suggested the wide-ranging and strictly enforced capital controls certainly played a role in eliminating the offshore ringgit market and constraining capital outflows. Malaysia managed its economy successfully without the IMF. The expansionary fiscal policy and improved confidence then combined to stimulate domestic demand.Footnote 53 Moreover, despite the setback to economic development, Malaysia continued to attract FDI, encouraged outward direct investment and adhered to its very pro-investor policy over the following decade.Footnote 54 By April 1999, Malaysia began receiving net capital inflows, the stock market picked up, the accumulation of reserve resumed and credit ratings were upgraded. The turnaround was accompanied by a notable strengthening of the balance of payments.Footnote 55 The ‘errors and omissions’ in the balance of payments (an indicator of unofficial capital flows) also shrank.Footnote 56

One likely reason for this performance was that Malaysia's policies during the crisis were better suited to its specific circumstances than those in the IMF program countries were suited to their circumstances. Such policies allowed Malaysia to maintain control of its own economic destiny and act in its own best interests. The policies had a far more benevolent impact on Malaysian society than did the IMF's policies in other crisis countries.Footnote 57 Malaysia's pre-crisis economic policy involved extensive affirmative action to improve the position of the native Malays (Bumiputras).Footnote 58 The Malaysian government had experience using economic policy to support social policy and consequently Malaysia's policies did not affect the poor as harshly. As one commentator stated, ‘the costs were not borne primarily by the poor and dispossessed, as occurred in some neighbouring states with great consequent social costs’.Footnote 59 As Athukorala noted, ‘the new policy measures enabled Malaysia to achieve recovery while minimizing social costs and economic disruptions associated with a more market-oriented path to reform’.Footnote 60

Support for capital controls began emerging after the Asian financial crisis. The IMF acknowledged in some staff working papers that the ‘successful experience of the 1998 controls so far is largely due to the appropriate macroeconomic policy mix that prevailed at that time’Footnote 61 and that the controls were effective because they ‘were wide ranging, effectively implemented, and generally supported by the business community’.Footnote 62 The introduction of the exchange controls and the currency peg was sound policy,Footnote 63 and such measures ‘led to substantial improvement in the sector's performance’.Footnote 64

In conclusion, Malaysia's reluctant approach to IMF reforms was rooted in its political history and pursuit of autonomy from international market forces.Footnote 65 In reforming its system, Malaysia was implementing home-grown policies. We would expect more rigorous implementation of home-grown policies than policies developed abroad, which is precisely what occurred in Malaysia relative to IMF-program countries.

The Malaysian economy recovered nicely following the introduction of the capital control-based reform. The Malaysian policies produced economic recovery with smaller declines in employment and real wages and rapid turnaround in the stock market. Economists continue to debate whether the Malaysian recovery under capital controls was superior to that of the IMF-program countries but it is clear that Malaysia's capital control based program delivered results as good, if not better, than IMF programs, and with far less damage to the poorer members of society.

C. Capital Controls in Europe: The Case of Iceland

The GFC triggered a transformation in thinking and practice around capital controls. While many countries implemented capital controls in the wake of the GFC (including Brazil, Indonesia, South Korea and Thailand),Footnote 66 the marked difference from previous crises was that controls on capital outflows also emerged in richer countries such as Iceland, Greece, and Cyprus.Footnote 67 In this section we examine capital control measures implemented in Iceland, as it was one of the worst-hit casualties of the crisis.

Before the GFC, Iceland's economy was booming and its high interest rate attracted short-term capital inflows of the order each year of Iceland's annual GDP.Footnote 68 Much of this money was engaged in classic ‘carry trade’, in which investors borrow in one currency at a lower interest rate so as to reinvest the proceeds in another currency at a higher rate, but at the price of absorbing massive exchange rate risk. Iceland's gross external indebtedness reached 550 per cent of GDP by the end of 2007Footnote 69—leverage levels that rendered its economy exquisitely vulnerable to external shocks.

When the banking crisis struck, the carry trade inflows quickly reversed, and Iceland's Krona rapidly fell in value. The Central Bank of Iceland initially tried to support the currency by purchasing Krona, but their net reserves were quickly exhausted and the major banks collapsed within a week. To prevent massive capital flight, and a complete collapse of the exchange rate, Iceland imposed capital controls and halted all foreign exchange transactions by October 2008.Footnote 70

In a full-blown crisis, Iceland had to approach the IMF and request a stand-by arrangement in order to prevent a complete currency collapse, restore confidence and stabilise the economy. In addition to the traditional advice of budgetary austerity and raising the interest rate, the stand-by arrangement included the imposition of controls on capital outflows.Footnote 71 Following approval of the IMF programme in late October 2008, the current account was reopened, with the Foreign Exchange Act being amended to allow only current account transactions, and with capital controls installed on both outflows and inflows.Footnote 72 Restrictions on outflows remained in place until March 2017, far longer than envisaged and well beyond what was necessary to stabilise the economy and forestall the crisis.Footnote 73 Throughout this period, Iceland tightened the restrictions several times and closed loopholes which participants were attempting to exploit.Footnote 74 The main capital control measures included:

• Prohibitions on investment in financial instruments denominated in foreign currency, financial cross-border transactions (except trade-related transactions) and withdrawals from Krona-denominated bank accounts.Footnote 75

• Strict limits on amount and duration of loans between domestic and foreign private parties to 10,000,000.Footnote 76

• Prohibitions on capital movements larger than 10,000,000 Krona per calendar year, with an obligation to submit foreign currency and a prohibition on foreign exchange cash withdrawals unless with proof of current transactions.Footnote 77

• Prohibitions on acting as a guarantor in domestic–foreign parties’ lending (except trade-related transactions).Footnote 78

• Prohibitions on trading in derivatives involving the Icelandic Krona against a foreign currency.Footnote 79

Thus, and unlike in the other case studies, Iceland's capital controls were implemented as part of a standby arrangement with the IMF. While Iceland's controls were initially envisaged to last for only two years under the IMF program,Footnote 80 they remained in place until 2017. These restrictions represented a crystallisation of the shift in thinking in the Fund on capital controls, and the measures have been well received by economists who believe the controls played a vital role in stopping capital flight, stabilising the foreign exchange market and limiting further damage to the country's economy.Footnote 81 At the same time, the controls remained in place long after the crisis abated and far from being ‘temporary’ simply became a longer-term tax on the domestic population, by unnecessarily increasing the cost of capital. The controls have also been criticised for eroding the trust of both domestic and foreign investors in the Icelandic economy. As will be addressed below, the controls also triggered a claim against the government by international investors for locking up their assets amidst the banking crisis.Footnote 82 Although Iceland prevailed in the dispute,Footnote 83 the claim generated publicity and added to the uncertainty about the country's fiscal situation among investors. Instead of being a calming force, the long-standing nature of the controls combined with the resolute attitude of the government was blamed for fanning the flames of nationalism.Footnote 84

D. Long-Standing and Extensive Capital Controls—the Case of China

In some emerging markets—such as Chile and Malaysia—capital controls have been occasionally used as a policy response to volatile short-term capital flows during crises. However, China has imposed long-standing capital controls throughout its modern history. Its restrictions on the movement of capital have been consistent, broad-based and numerous. Since opening up its economy over 40 years ago, China has transformed from a closed economy into an economic powerhouse driven largely by the market (under State guidance). Its opening up to international trade, especially since its accession to the WTO in late-2001, has been accompanied by a further loosening of restrictions on international transactions.

China's liberalisation has been well-sequenced and slow. Domestic factors, financial crises in Latin American and Asia, and lingering financial instability in the regional and global economy, have all shaped China's cautious approach to cross-border capital flows. China saw how the liberalisation of capital markets without adequate regulatory oversight and strong institutions has often led to crises in banking and balance of payments and sharp depreciations in currencies.Footnote 85 In particular, China noted how these factors cause social and political instability. As a result, China implemented explicit regulations and controls to restrict or restrain cross-border capital movements and protect its underdeveloped financial sector from external volatility.Footnote 86 This liberalisation has involved Chinese-style gradualism and experimentalism. Chinese scholars and policymakers have generally recognised that a loss of control of its cross-border capital flows could lead to an avalanche of capital outflows from China that could threaten the entire financial system.Footnote 87

1. A snapshot of China's capital control history

Before ‘opening up’, China had a highly centralised and controlled foreign exchange management system. All foreign exchange receipts were sold to the State and all foreign exchange payments were approved and allocated under mandatory national plans. Capital flows were minimal. Since opening up, China's liberalisation has undergone several distinct phases.

a) Phase 1 (1979–1993)

In the 1980s and early 1990s, capital flow mobility was restricted due to limited foreign exchange reserves and (coinciding with the Latin American debt crisis) a compulsory surrender system which forced firms to repatriate their foreign exchange earnings.Footnote 88 As China became increasingly open, various measures were undertaken to support exports and restrict imports. Domestic enterprises were allowed to retain a certain proportion of foreign exchange earnings. Moreover, the Bank of China began to operate foreign exchange swap operations that allowed enterprises to sell their excess retained foreign exchange to those who needed it.Footnote 89 Such measures relaxed exchange restrictions and thereby stimulated export-related capital flows.

Capital controls during this period adopted an ‘easy in and difficult out’ approach to avoid a balance of payments crisis.Footnote 90 Restrictions on FDI were gradually relaxed, and to attract investors more flexibility was given to foreign-funded enterprises together with generous tax treatment and certain ‘super-national treatment’. For example, China's Foreign Joint Venture Law granted approved non-resident investors the right to invest in China with no restrictions on the inward remittance of funds.Footnote 91

However, controls on non-FDI inflows were strictly enforced. Transactions were prohibited in most money markets and capital market instruments. Allowable inflows were subject to prior approval by the PBOC or SAFE. Additionally, China was very cautious about taking on external debt and this was subject to maturity requirements.Footnote 92

b) Phase 2 (1994–2000)

Phase 2 began in 1994 when China underwent major market-oriented exchange reforms. This included abolishing the foreign exchange retention system and allowing domestic enterprises to buy and sell foreign exchange through designated foreign exchange banks. In 1996, China shifted closer to market-norms by accepting the obligations of IMF Article VIII and announcing RMB convertibility on the current account, removing restrictions on making payments and transfers for international current transactions.Footnote 93

China did, however, maintain tight controls on the capital account. The differential treatment between the current and capital accounts resulted in current account transactions being used to evade restrictions on capital account-related payments. Various administrative measures were taken to control illicit capital flows. For instance, China strengthened its export verification system first adopted in 1991 and introduced a system to verify import payments to detect suspicious and disguised capital transactions under current account transactions.Footnote 94

Although China escaped the worst of the 1997 Asian financial crisis, it sustained indirect damage as rising expectations of an RMB devaluation, increased transaction costs and perceived financial and systemic uncertainties increased unauthorised capital outflows.Footnote 95 China learned from Korea, Thailand and Malaysia's experiences during the crisis and dramatically restructured its banking system afterwards and strengthened controls. In fact, financial stability became such a priority it was framed as a national security issue.Footnote 96

c) Phase 3 (2001–2012)

China's entry into the WTO marked a new stage of openness. With a commitment to further liberalise its financial service sector and keep pace with economic globalisation, China accelerated the opening of its capital account. Application for, and the approval of, FDI were both greatly simplified and the Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (QFII) scheme granted foreign investors direct access to China's capital markets.Footnote 97 Subsequently, in 2006, the Qualified Domestic Institutional Investors (QDII) scheme was introduced to allow qualifying domestic banks to make portfolio investments,Footnote 98 though with a combination of multi-tier and multi-stage strict approval procedures and a heavily regulated quota-based system. While such moves greatly liberalised China's market, we should not overestimate the extent of the liberalisation: China maintained a more restrictive regime than most other countries in terms of qualification, supervision, investment and administration of funds.Footnote 99

Following WTO accession, China's share of world exports and its trade surplus surged. Speculative capital inflows also greatly increased, putting upward pressure on the RMB.Footnote 100 Accordingly, China's primary focus was controlling capital inflows. For example, measures such as the ‘Provisions on the Merger or Acquisition of Domestic Enterprises by Foreign Investors’Footnote 101 and the ‘Notice on Domestic Residents to Engage in Financing and in Return Investment via Overseas Special Purpose Companies’Footnote 102 sought to strengthen the monitoring of capital inflows. Such measures were viewed as necessary but may have breached IMF Articles VIII and XIV and GATS Article XI as barriers to payments and transactions relating to specific commitments in financial service sectors.Footnote 103

Overseas investment by Chinese enterprises also became less restricted and restrictions on the issuance of bonds abroad by domestic institutions were loosened.Footnote 104 The policy was characterised as ‘difficult in and easy out’.Footnote 105

2. China's current capital controls

It has been suggested that the appropriate control of cross-border capital flows has been key to China's stable growth and economic miracle. Despite long-standing and tight controls, China's controls have never been watertight.Footnote 106 Since President Xi Jinping took office, China has made several attempts to strengthen capital controls to increase their effectiveness. The capital flow management framework has been upgraded and China has established a more balanced approach to inflows and outflows within its capital control regime.Footnote 107

a) Measures on outflow controls

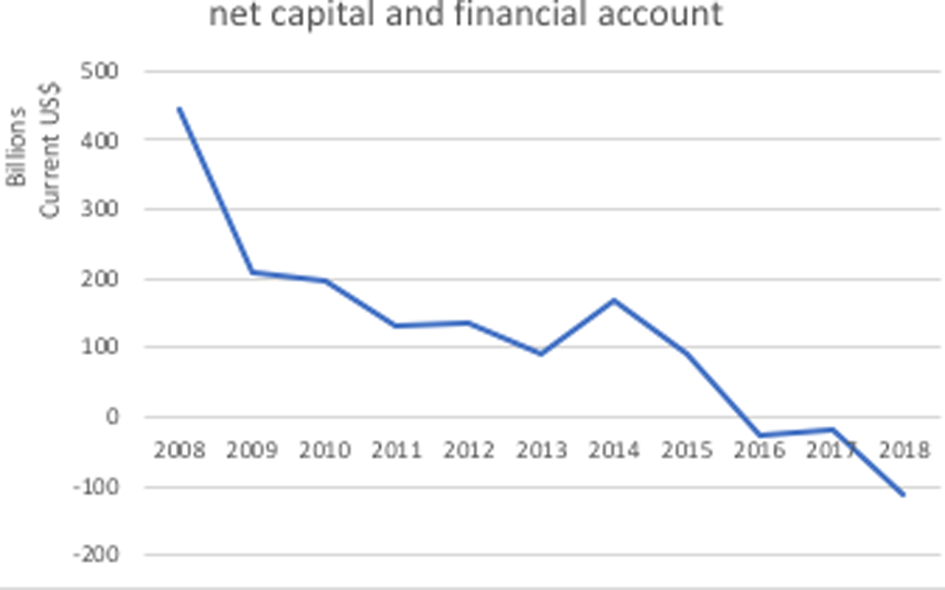

The recent decade has witnessed a shift in the balance of payments from a ‘twin surplus’ to a shrinking current account surplus and a deficit in the capital and financial account, coupled with a dramatic swing from net capital inflows to large net outflows (Figure 1). This swing is driven by outbound investment as Chinese companies increase overseas activities and RMB depreciations and concerns about China's economic outlook spark capital flight.Footnote 108

Figure 1: China's net capital and financial account

Source: IMF, Balance of Payments Statistics Yearbook and data files.

While China's capital account is not fully open, the country is not immune from surging capital flight. This trend is manifested in the high level of ‘errors and omissions’ in the balance of payments, which is a proxy for capital flight. While many restrictions on cross-border capital outflows have been loosened, extensive controls are still applied through restrictions including on household residual foreign exchange and on outward FDI and portfolio investment.Footnote 109

The supervision of capital outflows has been extended from corporations to individuals. A quota-based limit on overseas RMB withdrawals for individuals was set at 10,000 yuan per day and 100,000 yuan per year. Individuals can make foreign transfers of up to US$50,000 per year and transferring money overseas for the purpose of purchasing real estate and investment-type insurance products is prohibited.Footnote 110

In terms of capital account, China introduced rules to simplify approval procedures for outward direct investment. In its 2018 reforms, China also relaxed its outbound investment schemes for investing in securities overseas. Moreover, by resuming the Renminbi Qualified Institutional Investors (RQDII) program and expanding quotas for several other outbound investment programs, Chinese regulators are perhaps moving to relax capital controls after a period of tightening.Footnote 111 Simultaneously, however, checks on the authenticity and legality of outward investments and reporting requirements on investment details have been strengthened.

Outbound lending by Chinese domestic enterprises remains subject to limitations on the size and term of the loan and requires an equity relationship between the lender and borrower. Enforcement was further tightened in 2016 with additional examinations on whether the overseas borrower is suitable in terms of the size and reasonableness of use.Footnote 112

Besides administrative controls, monetary and macro-prudential measures were also introduced which have significantly impacted capital outflows—examples include the one-year 20 per cent unremunerated risk reserve requirement for financial institutions buying foreign currency forward contracts and other derivative transactions,Footnote 113 and the reserve requirement on foreign financial institutions’ RMB deposits at Chinese domestic financial institutions.Footnote 114

b) Measures on inflow controls

As noted earlier, China has successfully restricted inflows to reduce the volatility of cross-border capital. China has relaxed controls in this space in recent years.

In October 2019, China introduced several measures to loosen regulatory controls over foreign exchange income payments in respect of both current and capital account cross-border transactions.Footnote 115 Portfolio flows that had been restricted and subject to limits on amounts were encouraged. The new rules also removed the three-month lock-up period and the 20 per cent repatriation limit; thus allowing Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors (QFII) to repatriate the principal and profits from their securities investments in China at any time. However, SAFE retains its power to exercise macro-prudential supervision over the repatriation of capital by QFIIs and may continue to impose temporary restrictions on QFII repatriations when required.Footnote 116

Due to strict controls over the past decade, China has not been inundated with ‘hot money’ at least in the portfolio investment sector. Short-term speculative inflows can make a sudden exit that causes panic and threatens economic stability. Therefore, inflow controls remain in place to monitor capital inflows and control speculative inflows.Footnote 117

3. Some features of China's capital controls

China's capital control regime is quite distinct from that of most emerging markets. For instance, China's controls are generally ‘direct administrative restrictions’ such as authorisation requirements, time requirements, quantitative limits and direct prohibitions. There are few market-based measures that discourage capital flows by making them more costly.

Moreover, the management of cross-border capital flows has long-term and short-term aspects. The long-term aspect is related to a gradual and cautious liberalisation strategy and the short-term aspect to macro-economic stability.Footnote 118 The controls are imposed in both procyclical and countercyclical ways, with close consideration paid to domestic and international circumstances which threaten China's stability. Short-term controls are generally tightened in response to abrupt surges in illicit capital flows or macroeconomic variables and do not represent a shift away from the policy of continuing financial market reform.

China's current controls are nuanced with more stringent measures over short-term flows than long-term flows. China's strict controls, especially over the compositions of capital inflows, ensured it was largely unaffected by the GFC. China's preference for long-term inflows (dominated by FDI),Footnote 119 and strict controls which reduced opportunities for speculative activities, limited China's vulnerability to external shocks and spared it from the direct impact of the GFC.Footnote 120

Finally, the regulatory regime has shifted from an asymmetrical one-way focus on capital outflows to an equilibrium of more balanced, two-way cross-border capital flows. This feature will likely continue in China's capital control regime.

4. Conclusions on China's (continuing) experience

Cross-border capital flows are closely linked to China's integration into the global economy and domestic financial and economic stability. China has significantly improved its controls on cross-border capital flows since its accession to the WTO. The opening of China's capital account has been gradual, and based on a strategy of being ‘prudent and steady’.Footnote 121 This gradual approach has brought cross-border capital flows to equity and bond markets and other financial instruments, transactions which were previously prohibited.

China still has a long way to go before it fully liberalises capital flows and makes the RMB fully convertible; and until then, a multitude of capital controls will remain. The one constant though is change—China often experiments and changes course based on its economic situation and priorities. Some measures are long-standing, whereas others have been loosened or strengthened depending on the economic climate. Another constant is criticism of the effectiveness of China's long-standing capital controls. However, China's history suggests that the maintenance of cross-border capital controls will be a condition for stable and sustainable growth in China in coming years.

The extensive and inconsistent use of capital controls causes concern about China's compliance with its international commitments. Section II will address the consistency of capital controls with international economic law.

II. Capital Controls under International Economic Law

As mentioned above, there has been a rethink about the usefulness of capital controls following the boom–bust cycles of the 1990s onwards, and the 2008 GFC. Even the IMF, which for decades saw controls as distortionary and ineffective, has explicitly acknowledged their usefulness, albeit on a temporary basis in crises, and included them in assistance packages.Footnote 122

Somewhat strangely, while the economic literature has long been filled with debates about the effectiveness of capital controls, the legal literature has been mostly silent as to their legality. There is not even a simple answer to the question of whether a specific control measure can be introduced or maintained, as the answer depends on the language in a country's international treaties and commitments thereunder. From the multilateral point of view, IMF rules provide a floor for investor protection and some policy space for members to adopt restrictions on cross-border capital flows. The GATS likewise can be viewed as a floor given that most WTO Members have not committed to complete liberalisation of the financial services sector. Bilateral investment treaties and regional and bilateral free trade agreements tend to contain stronger treaty language and higher-level commitments. But, far from being certain, the legal framework is a patchwork quilt of over 3,000 BITs and FTAs.Footnote 123

This section does not seek to provide a comprehensive overview of all 3,000+ treaties. Instead, it describes the fragmentation of international disciplines when it comes to capital controls and offers select examples to evaluate whether a given control is consistent with the language of international treaties. In this way, readers will get a flavour for the legal complexities and understand how treaty language is the critical factor in determining the consistency of any given capital control with a commitment undertaken in a trade or investment agreement.

A. Capital Controls and the IMF

Although the IMF is best known for its financing and surveillance functions, it has important regulatory powers.Footnote 124 Several provisions in the IMF Articles of Agreement (AA) regulate the use of capital controls. Article VI:3 of the AA provides that, ‘Members may exercise such controls as are necessary to regulate international capital movements ….’ This article is routinely cited as support for a member's right to impose capital controls. Yet the provision's history is enlightening, as in the original Articles it did not even mention capital flows and controls. Regulation of capital flows remained a State prerogative. In other words, on inception the IMF was a purely monetary institution focussed on monetary stability.

Article VIII:2(a) of the AA, however, serves in some way to limit States’ ability to fully control capital flows as it gives the Fund a limited ability to oversee cash flow issues related to ‘restrictions on the making of payments and transfers for current international transactions’ and ‘unduly delayed transfers’. Thus, Members are obliged not to impose restrictions on the making of payments and transfers for current international transactions,Footnote 125 or unduly delay transfers of funds in settlement of commitments.Footnote 126

On its face, Article VI:2(a) is unconcerned with capital transactions. The legal definition of ‘payments for current transactions’ in Article XXX(d) sets out the types of transactions this includes:Footnote 127

(1) all payments due in connection with foreign trade, other current business, including services, and normal short-term banking and credit facilities;

(2) payments due as interest on loans and as net income from other investments;

(3) payments of moderate amount for amortization of loans or for depreciation of direct investments; and

(4) moderate remittances for family living expenses.

The reason for the limitation lies in the historical context of the post-World War II landscape. International obligations were narrowly drafted, and the Fund's limited mandate over ‘current transactions’ considered as a matter of payments and transfers to the exclusion of ‘capital movements’ because at Bretton Woods the liberalisation of trade exchange and financial facilitation was not considered relevant.Footnote 128 With the Keynesian approach to economic liberalism – which saw government interventionism as necessary to correct and/or curb market failures – being the dominant mindset among governments, unrestricted capital movements were discouraged as they could serve as a means to encourage speculative trading, prevent exchange rate stability and lead to volatility.Footnote 129 Moreover, the Fund's purpose was to ensure that the competitive currency devaluations which destabilised the system (and governments) in the years leading to World War II would not occur again. For this reason, the Fund was created ‘to allow monitoring collective efforts towards currency stability and was only granted sufficient authority to ensure that cross-border current transactions—ie the financial transactions allowing for the realisation of international trade exchanges—remained stable and under control’.Footnote 130 The institution, therefore, was established to stabilise and serve as a quasi-lender of last resort to assist Member States in times of crisis.

While the distinction between ‘capital movements’ and ‘current international transactions’ was fine in the 1940s, the evolution of modern banking and international financing combined with the radically changing nature of international trade practices has further narrowed the distinction. Contributing to the shift was the ideological evolution which embraced financial flow liberalisation as positively contributing to economic growth and development (most notably in the 1990s) and the increasingly interconnected nature of international trade liberalisation and cross-border transactions, which to a large extent depend on free capital movements. This shift was not anticipated during the Bretton Woods period, and neither was the development of trade-related financing as a self-standing cross-border and frontierless financial sector capable of creating wealth (and also instability).

As one of the authors has detailed elsewhere, the Fund has over time (1) asserted oversight and responsibility in relation to its Members’ financial policies; (2) taken steps to oversee capital controls matters; and (3) implemented a skilled strategy to progressively expand its mandate from monetary matters to financial systems.Footnote 131 The Fund accomplished this shift through a reinterpretation of principles and the evolving views of Members in line with the changing nature of trade and finance. In so doing, the IMF has essentially made the distinction between current transaction and capital movements irrelevant since both account transactions and capital controls are now viewed as within the scope of a ‘foreign exchange transaction’, which is unquestionably included within the Fund's mandate.Footnote 132 The main tool for creating a mandate to oversee capital movements occurred through the ‘Article VI Byroad’, in which staffers used the Fund's exchange rates attributions (under Article I) and the Members’ obligation to cooperate with the IMF in relation to exchange arrangements (under Article IV) to indirectly expand the institution's ability to oversee capital movement policies as such policies could possibly impact on the overall stability of the international exchange system.Footnote 133 Made possible through the 1977 Decision on Surveillance over Exchange Rate Policies, which amended the AA and allowed for a shift in the Fund's mandate from competence merely over exchange rate stability into a much larger role encompassing the stability of the exchange system itself and entitling the Fund to monitor Members’ compliance with IMF requirements. In so doing, the Fund could justify intervention as necessary to safeguard Fund resources and prohibit a Member from using capital controls in any manner which would lead to arrears in capital payments.

Thereafter, the Fund increased its role in assisting Members with currency policy adjustments, including those aimed at responding to surges in capital movements, as it seized and entrenched its authority on the regulation of capital movements. For some time, the Fund's orthodoxy was to prevent capital controls. Its thinking has now shifted, as exemplified in its dealings with Iceland, where it was obvious that in a time of severe balance of payments (BOP) difficulties, financing alone was not a solution and that exchange and capital restrictions were needed.Footnote 134

To accommodate financial liberalisation, and against the backdrop of financial crises over decades, the Fund has expanded to encompass an evolving role in overseeing financial sector stability. Both capital account transactions and capital controls are now commonly viewed as ‘foreign exchange transactions’,Footnote 135 as monetary stability can be impacted by unpredictable capital flows. This surveillance role is grounded in the legal authority of Article IV, and in Fund decisions taken in 1977, 2007 and 2012.Footnote 136 For example, the 2012 Decision expressly extends the Fund's surveillance role in relation to capital flows:

the Fund will focus on issues that may affect the effective operation of the international monetary system, including … spill overs arising from policies of individual members that may significantly influence the effective operation of the monetary system …. The policies of members that may be relevant for this purpose including … policies respecting capital flows.Footnote 137

In so doing, the IMF granted itself authority to discuss with its Members their capital account policies and provide policy recommendations to the extent that these policies may significantly affect economic and financial stability.Footnote 138

The IMF's Institutional View (2012) on capital flows provided a macroeconomic framework for consistent policy advice on managing capital flows. It acknowledges that, while capital flows can have considerable benefits, they also carry inherent risks. Therefore, the liberalisation of the capital account needs to be well-planned, timed and sequenced.Footnote 139 The ‘institutional view’ is often cited as a revolutionary departure from IMF's own orthodoxy, establishing a set of international principles in respect of States’ capital account management. Yet the ‘Institutional View’ is essentially a set of guidelines and thus not binding. It does not create members’ rights and obligations under the Fund's AA or under other international agreements.Footnote 140

A surprising aspect of the Fund's mandate expansion is that its legality was rarely challenged and attendant academic literature is virtually non-existent. Again, one of the authors has recently concluded that the Fund's expansion in mandate through creative interpretation and the related ‘Article IV byroad’ is legally valid, and in fact necessary for the Fund to remain functional in responding to financial developments impacting the international community. This conclusion was reached after an analysis through the lens of international legal personalities and by considering the ‘spirit’ of the AA, in line with the international legal theory applicable to international organisations.Footnote 141 The expansion to include capital movements is by no means the only time the Fund has widened its powers. Such expansions have also occurred in relation to developing economies’ structural difficulties, debt relief packages, provisions on corruption and conditions relating to human rights. However, that Members allowed these expansions to occur—and in some cases requested them—without addressing the ‘institutional constraints’ is remarkable. While increasing the Fund's formal jurisdiction over the capital account has been discussed, these have proven to be controversial and there seems little appetite for increasing the Fund's formal mandate.Footnote 142

B. Capital Controls and Trade Agreements

Capital controls can affect trade through numerous channels, such as the price of products, transaction costs and portfolio diversification. Capital controls raise transaction and other trade-related costs and have a similar effect to quantitative restrictions on goods and services. Controls can also potentially limit business opportunities for financing trade, thus inhibiting it.Footnote 143 Thus, capital controls can be seen as inimical to the international trade regime which seeks to promote trade liberalisation and reduce trade barriers. While the objective of the international trading system is not to liberalise the cross-border movement of capital, trade liberalisation cannot be achieved if international transfers and payments made in conjunction with services transactions are restricted. The GATS is designed to provide WTO Members with some policy space to deploy capital controls, so long as Members do not bind themselves to complete liberalisation in their Schedule of Commitments. Many FTAs are modelled on the GATS but contain deeper and wider liberalisation commitments. Other FTAs have opted for a different architecture in the form of a ‘negative list’ approach, whereby market openings apply across-the-board except for scheduled reservations. The trend is towards multi-issue trade agreements which provide for investment (commercial presence in services terminology) through separate disciplines on trade in services and investment, which facilitate a greater level of linkage between trade and investment across signatory parties.Footnote 144 These modern FTAs which contain investment provisions or investment chapters which usually have a broader effect than stand-alone BITs. Investment provisions in the FTAs will be analysed together with BITs in the next section. This section will focus on GATS and the trade context of FTAs and the relevant jurisprudence concerning capital controls.

1. GATS discipline on capital controls

The GATS approach to capital controls differs from the IMF, and while the GATS does not advocate for the liberalisation of financial services, the starting point is that restrictions on capital movements are impermissible in so far as they would impede upon a trade in services liberalisation commitment. The GATS uses a ‘positive list’ approach to scheduling commitments, meaning WTO Members are not obliged to liberalise or offer market access or national treatment to any sector, unless otherwise specified in its schedule of commitments. Article XI of GATS prohibits any restrictions on international transfers and payments for transactions relating to specific commitments.Footnote 145 Therefore, capital account liberalisation is limited and conditional, in that a Member is only obliged to liberalise current or capital account movements in particular sectors where it has made commitments, subject to the member's rights and obligations under the IMF's AA.Footnote 146

If a market access commitment is made in a specific sector, the liberalisation of capital movements is required. Capital control measures used to restrict the movement of capital in that particular sector would be inconsistent with the market access commitment. Footnote 8 to GATS Article XVI guarantees market access where the cross-border movement of capital is an ‘essential part’ of the services under Mode 1 (cross-border supply) and Mode 3 (commercial presence) and the member must allow such movements of capital.Footnote 147 The scope of footnote 8 is untested, but under one interpretation, it is limited to covering only the capital movements inherently linked with the service itself, leaving payments and repatriation of capital outside the purview of the footnote. Therefore, while the taking of deposits or a loan made from a non-resident bank to a domestic customer would involve both a services transaction and an essential capital movement (in the form of the taking of the deposit or loan and movement of money, respectively) the provision of financial advisory services requires no capital movement and would not fall within the scope of footnote 8.Footnote 148

If this interpretation is correct, measures that restrict repatriation of funds such as those implemented by both Chile and Malaysia are not covered by footnote 8.Footnote 149 On the other hand, Chile's controls imposing minimum four-year maturity requirements for bonds issued for non-residents were intended to increase the cost of capital inflows and expected to discourage short-term inflows.Footnote 150 The measure is inconsistent with the market access commitment to the cross-border supply (Mode 1) on the purchase of bonds (included in Chile's commitment on CPC 8132 purchase of public-offered securities),Footnote 151 as it prohibits the movement of capital for bonds with a tenor less than four years.

Where the service is supplied through the commercial presence of a provider, Members are required to liberalise capital inflows in the establishment and post-establishment phases of the investment.Footnote 152 Take Chile's capital controls of the 20 per cent URR on foreign loan and portfolio investment.Footnote 153 If Chile undertook a market access commitment on the supply of loan or equity services through the commercial presence in its territory of a service provider from another member (Mode 3) under the GATS, the Chilean measure would reduce the capacity of foreign service providers to transfer money into Chile. A comparative advantage of foreign service providers is their access to better sources of funding. A market access commitment under Mode 3, without allowing foreign service providers to bring capital into the host country to set up business would be of little value.Footnote 154 Fortunately, Chile abolished these capital controls prior to the advent of the WTO as these controls would have been inconsistent with their commitments.

Similarly, national treatment commitments prohibit a Member from according foreign services providers less favourable treatment than their domestic counterparts.Footnote 155 Controls on capital flows, however, will significantly reduce the capacity of foreign service providers to transfer capital into the host country. Although the GATS provision on national treatment does not directly refer to capital controls, the negative effect on foreign service providers could amount to a de facto discrimination against the foreign service suppliers, especially for those who rely heavily on external funding.

The GATS provides certain exceptions from these obligations and entitles members to introduce capital controls under certain conditions, namely to comply with a ‘request’ from the IMF,Footnote 156 to protect against BOP difficulties or external financial difficulties,Footnote 157 and to take prudential measures to maintain the integrity and stability of the financial services system.Footnote 158 In each case, safeguards ‘shall be consistent’ with the IMF Articles, and each exception is subject to substantive conditions that raise a host of issues.

First, restrictions ‘at the request’ of the IMF may be illusory in terms of whether there may be circumstances foreseen by Article VI:1 of the IMF AA where the Fund requests a member to adopt capital controls.Footnote 159 In practice, a borrower ‘voluntarily’ reaches an agreement with the IMF—the IMF could recommend a member impose controls, however, it never ‘requests’ the country to initiate capital controls. Moreover, the Appellate Body in Argentina–Textiles held that, for a capital control measure to be consistent with WTO obligations, the measure must arise from a ‘legally-binding agreement’ stemming from the IMF Articles.Footnote 160 Voluntary agreements, policy pledges and recommendations do not create legally-binding obligations and thus are not covered by Article XI:2.Footnote 161

Second, regarding the BOP exception, controls to restrict capital outflows may be necessary to address capital flight and maintain currency reserves. However, it remains unclear whether capital controls can be invoked on inflows for BOP reasons.Footnote 162 The BOP exception also limits control measures by requiring them to be non-discriminatory, temporary and necessary.Footnote 163 These requirements intend to limit the negative impact of the control measures on Members’ commitments under the GATS, and terms such as ‘necessary’ carry significant interpretive meaning in this context. The application of these limitations has not been tested in dispute settlement and thus the depth and scope of the provision remains unclear.Footnote 164

Finally, the extent to which capital controls can be excused by the prudential carve-out clause contained in paragraph 2(a) of the GATS’ Annex on Financial Services has for some time been subject to debate. For instance, some have argued that the prudential clause only applies to Basel-type measures (ie capital requirements and buffers) which do not discriminate by residency or currency, while others took a broader approach by suggesting that micro and macro-prudential regulations (including capital controls) must complement each other to preserve the ‘integrity and stability of the financial system’.Footnote 165 The WTO panel and Appellate Body reports in Argentina—Financial Services have to a large extent clarified the picture by confirming that governments have considerable leeway in introducing prudential measures. The dispute involved eight financial, taxation, foreign exchange, and business registration measures which, according to Argentina, constituted ‘anti-abuse measures which [were] essential tools for enforcing national tax laws, guaranteeing taxation and tax collection, preventing fraudulent practices, tax evasion and tax avoidance, as well as the erosion of national tax bases’.Footnote 166 To Panama, however, Argentina's measures infringed upon its market access commitment in the financial services sector.Footnote 167

The Panel began its analysis by stating

Argentina must demonstrate that two requirements have been met in order to avail itself of the exception, namely: (i) that the measure in question was taken for prudential reasons and (ii) that the measure is not being used as a means of avoiding its commitments or obligations under the GATS.Footnote 168

The Panel then clarified the limits of the provision, making several important findings.Footnote 169 For instance, the panel drew a distinction between ‘prudential measures’ and ‘measures taken for prudential reasons’, finding that in order to fall within the provision ‘it is the reason which must be “prudential” and not the measure per se’.Footnote 170 Stated more clearly, the prudential factor relates to circumstances justifying the measure and not simply to a certain type of measure.Footnote 171 In addition, the Panel found the prudential clause to be ‘preventive or precautionary’ in natureFootnote 172 and could include an ‘extremely broad’ number of possible measures in quantitative terms.Footnote 173 In this regard, the prudential reasons listed in paragraph 2(a) are indicative rather than exhaustive. Most importantly, the Panel found that paragraph 2 should be read in a broad manner, expressing concerns as to the ‘serious systemic implications of the narrow interpretation’ of such provisions.Footnote 174 More particularly, the Panel found that Members ‘are entitled to determine the level of protection they consider appropriate’Footnote 175 and that the ‘nature and scope of financial regulation at different times reflect the knowledge, experience and scales of values of governments at the moment in question’.Footnote 176 In this regard, the Panel stated that Members:

should have sufficient freedom to define the prudential reasons that underpin their measures, in accordance with their own scales of values . . . such as ‘the protection of investors, depositors, policy holders or persons to whom a fiduciary duty is owed by a financial service supplier’ or ‘the integrity and stability of the financial system’[.]Footnote 177

The final point worth noting is that the Panel found that the temporal nature of a particular prudential measure was to be read in light of the causes justifying the measure and that a measure taken for prudential reasons ‘can remain in place … for as long as the factual circumstances that justified their adoption continue to exist’.Footnote 178 In this regard, the Panel stated that

nothing in the ordinary meaning of the words ‘prudential reasons’ conveys the idea of a time-limit … as a matter of principle [issues raising prudential concerns] may give rise to long-lasting measures to avoid the recurrence of similar situations in the future.Footnote 179

By taking this position, the Panel avoided myopically focusing on trade specific obligations and instead demonstrated its awareness of the trade regime as part of a larger, integrated world.Footnote 180

Thus, although the GATS does not aim to liberalise the cross-border movement of capital per se, it contains obligations for Members who have undertaken specific sectoral commitments. The prohibition on restrictions on capital inflows and outflows applies in all sectors where a commitment has been made. For sectors where no commitments have been made, Members are entirely free to adopt control measures. The policy space to deploy capital controls under the GATS, therefore, varies across different countries, depending on their specific commitments in relevant sectors and modes of supply.

2. Capital controls and trade context of FTAs

Due in part to the slow pace of the WTO's Doha Round of trade negotiations, bilateral and regional FTAs have flourished of late. Like the GATS, FTAs facilitate cross-border capital flows commitments which are contained in the market access and national treatment liberalisation part of the schedule of commitments. Again, the purpose is not to permit payments and transfers per se, but to permit the cross-border establishment and development of services providers. Thus, where a party to an FTA has made no commitment to facilitating cross-border payments and transfers, the FTA does not prevent the signatory from having recourse to capital controls.

However, all FTAs are not structured in the same way and some economies have sought to ‘raise the bar’ in terms of the scope and level of commitments. Although all FTAs are committed to trade liberalisation through the reduction of barriers and thus parties make GATS+ commitments, not all are comparable in terms of objectives, coverage, depth and sophistication. Moreover, FTA treaty practice is constantly evolving and many countries agree to multiple forms of FTAs.Footnote 181 The depth and breadth of commitments respective economies make for trade in services vary substantially across members and agreements. This could give rise to inconsistent rights and obligations under different agreements and the GATS.

China has actively embarked on many FTAs since its accession to the WTO. However, due to different treaty languages and commitments under different FTAs, some Chinese capital control measures may be maintained under some FTAs and infringe commitments in others. A careful review of China's capital control regime confirms the country's cautious liberalisation of its capital account usually comes with safeguards to preserve its ability to intervene if market outcomes prove problematic. Yet there are major inconsistencies in China's regime. For instance, China's insurance sector is not yet fully liberalised,Footnote 182 and it prohibits transferring money overseas for the purpose of purchasing investment-type insurance including investment-linked life insurance;Footnote 183 yet rather surprisingly, China has made market access and national treatment commitments on the cross-border supply of all insurance and insurance-related services in FTAs with Singapore and Korea. While China has carved out exceptions for the cross-border supply (Mode 1) of reinsurance, insurance for certain international transport sectors and brokerage for large-scale commercial risks,Footnote 184 China's prohibition on residents purchasing investment-type insurance from non-residents would be inconsistent with its market access and national treatment commitments to allow the cross-border supply of such insurance services. A market access commitment is meaningless if transactions cannot be made across borders, and this limit accords foreign insurance service providers less favourable treatment than Chinese domestic insurance providers.

China did not include insurance and insurance-related services in its financial services commitments in the ASEAN–China FTA in 2007.Footnote 185 Therefore, controls on the investment-type insurance can be maintained under China's initial commitment. The agreement, however, was recently upgraded with all parties offering improved trade in services commitments. With acceleration of China's opening up in its financial sector, insurance and insurance-related services including life, health and pension/annuity insurance were added in the second package of Chinese commitments.Footnote 186 The Chinese government is therefore binding itself to market access and national treatment in the cross-border supply of insurance services and is undertaking not to impose any measures that restrict market entry or the operation of insurance services. The control measure that restrict residents from purchasing investment-type insurance from foreign service providers is therefore inconsistent with China's upgraded commitments in the ASEAN–China FTA.

Similarly, the Chinese QDII quota limit can be maintained under some of China's FTAs, even though this measure is inconsistent with obligations contained in others. China introduced QDII programmes as part of its capital account liberalisation. Although the quota imposed on QDII was expanded in 2018, total and individual quotas were implemented. In the China–Korea FTA, China commits to providing market access for cross-border supply in the securities sector, except where service suppliers in Korea provide the following services to the Chinese QDII: trading for account of QDII; providing securities trading advice or portfolio management; or providing custody for overseas assets of QDII.Footnote 187 Since QDII-related services are removed from Chinese commitments in the securities sector, China's quota limit on QDII is consistent with the China–Korea FTA.

China undertakes slightly different commitments for the securities sector under the China–Singapore FTA. The market access commitment for cross-border supply is unbound with the exception that foreign securities institutions may engage directly in B share business (without a Chinese intermediary).Footnote 188 QDII-related services are not included in the exception. In other words, the inclusion of the QDII-related services in the market access commitment under Mode 1 limits China's ability to place controls on capital movements in this sector in order to restrict the normal course of the business. The imposition of a QDII quota is inconsistent with China's commitment under the China–Singapore FTA.