I. INTRODUCTION

In the past few decades, globalisation has led to an enormous increase in cross-border transactions in various areas, such as foreign direct investment and trade. According to World Bank data, global net outflows of foreign direct investment rose from USD13.04 billion in 1970 to a peak of USD3.196 trillion in 2007. In 2017 it was USD1.525 trillion.Footnote 1 The rise in cross-border business transactions related to Asia is particularly significant. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Asia continues to be the largest recipient of foreign direct investment in the world, with greenfield project announcements doubling in value.Footnote 2

With the growth of cross-border transactions, the potential for disputes and the demand for effective and efficient resolution of them have increased. There are various methods for international commercial dispute settlement if private negotiation does not achieve a compromise, and the two most important methods are arbitration and litigation. However, both arbitration and litigation present challenges.

Arbitration cannot be used for some cases or disputes. Some claims, such as breach of patent rights, are non-contractual and some disputes, such as those arising from employment, are non-arbitrable.Footnote 3 Arbitration also has its disadvantages or drawbacks. Sundaresh Menon, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Singapore, discussing the establishment of international commercial courts, has suggested that there are four issues that ‘threaten the continuing vitality of international commercial arbitration’: (a) judicialisation; (b) lack of ethical standards; (c) unpredictability in enforcement due to the ad hoc nature of courts’ oversight; and (d) unpredictability in arbitral decisions due to lack of jurisprudence.Footnote 4

Chief Justice Menon's comments suggest that conceived as an ad hoc, consensual, convenient and confidential method of resolving disputes, arbitration, by its very nature, is not able to provide an authoritative tool to facilitate global commerce. Nor can it, on its own, adequately address issues such as the harmonisation of substantive commercial laws, practices and ethics.Footnote 5

As to litigation, domestic courts are often associated with sovereignty and considered to be a non-neutral forum. Most parties prefer private conflict resolution over public trials and, in particular, are reluctant to choose a court of the country of the other side. They may worry about corrupt or protective judges and be unfamiliar with or sceptical of the local law, language and custom. They also expect consistent outcomes from uniform agreements, which is often difficult to achieve in domestic courts.Footnote 6

The perceived problems of arbitration and the unpopularity of domestic courts, as well as the increasing global (and in particular Asian) need for cross-border business dispute resolution, have fuelled the establishment of a series of international commercial courts or similar institutions. Such courts provide a new mechanism offering some of the advantages of both litigation and arbitration for the international business community. They include the Dubai International Financial Centre Courts (DIFC), the Qatar International Court (QIC), the Abu Dhabi Global Market (ADGM) Courts and the Singapore International Commercial Court (SICC). Among these new institutions, the SICC stands out as a successful example adapted from the arbitral model (with strong party autonomy and flexible procedural rules as its central features) but underpinned by judicial control.Footnote 7 At the same time, several other cities have launched, or are planning to launch, similar initiatives, such as Amsterdam, Dublin, Frankfurt, Paris and Brussels. In 2018 there were 24 global commercial courts.Footnote 8

In 2013, China launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). It is not only a trading channel, but also a new strategy to facilitate greater Chinese participation and engagement in the global economy, particularly in Asia,Footnote 9 and to shape a new structure for global economic governance.Footnote 10 With its outward economic expansion and significant overseas investment, China faces an increasing number of civil and commercial disputes with foreign dimensions. In the five-year period 2013–2017, Chinese courts decided approximately 75,000 foreign-related civil and commercial cases, and provided international judicial assistance for approximately 15,000 cases.Footnote 11 As a result of the BRI China is expected to be more deeply involved in adjudicating commercial cases relating to China and, potentially, to have a greater say in rule making for international business and trade.

To share the expanding international business dispute resolution market, better protect its investments and have a greater say in the harmonisation of substantive international business law, China has developed its own international commercial courts. On 23 January 2018, the Chinese Communist Party (CPC) and State Council jointly enacted the policy statement ‘Opinions on Establishing the Belt and Road Dispute Settlement Mechanism and Institutions’, which stated that China would establish an international commercial court. An efficient, neutral, and reliable dispute resolution mechanism is desirable to address the inevitable transnational disputes that are likely to arise from the BRI.Footnote 12 Accordingly, on 29 June 2018, the First and Second International Commercial Courts (‘CICC’ collectively) affiliated with the Supreme People's Court (SPC) were established in Shenzhen and Xi'an respectively, and judges were appointed.

China has a multilayered court system. The SPC has jurisdiction over the whole nation and supervises all ‘local people's courts’ and ‘special people's courts’.Footnote 13 Local people's courts can be divided into three levels in the following order of seniority: high people's courts at the level of provinces, special municipalities and autonomous regions (in total 32); intermediate people's courts at the level of prefectures or their equivalent; and basic people's courts at the level of counties, municipal districts or their equivalent. In China, the courts at a higher level supervise the trial work of lower-level courts under their jurisdiction.Footnote 14 Special people's courts only have jurisdictions in respect of special cases and include military courts, maritime courts, intellectual property courts and financial courts, etc.Footnote 15 As the CICC is a division of the SPC, it should not be considered to be part of the local or special people's court system.

The ‘Regulations on Certain Issues regarding Establishment of the International Commercial Courts’ (the Regulations) promulgated by the SPC came into effect on 1 July 2018.Footnote 16 The Regulations are very concise and are analysed below. The CICC's official website (http://cicc.court.gov.cn/) was also launched. In December 2018, further working rules of the CICC were promulgated by the SPC. They include the ‘Notice of the Supreme People's Court on Determining the First Batch of International Commercial Arbitration and Mediation Institutions to be Included in the One-stop Diversified Settlement Mechanisms for International Commercial Disputes’,Footnote 17 the ‘Rules regarding the Procedures of the International Commercial Court of the Supreme People's Court (Trial Version)’Footnote 18 and the ‘Rules regarding the Work of the Committee of International Commercial Experts of the Supreme People's Court (Trial Version)’.Footnote 19

These establish the basic framework for the CICC. It is noteworthy that the preparatory work establishing the CICC took place over a relatively brief period. This has resulted in many issues not being well understood and regulatory obstacles not being well addressed as a result of certain statutory impediments (see further analysis below).

In March, 2019, the CICC started hearing three cases assessing the validity of arbitration clauses.Footnote 20 The CICC has a potential impact on the international business community, which may either choose the CICC as the forum court, or face litigation heard by the CICC when the case is assigned to the CICC by the SPC. Against this background, this article aims to provide a detailed and critical analysis of the operation of the CICC and supplement existing studies by providing theoretical input into several key issues involved.

II. THE CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FACING THE CICC

Despite China's ambitious plans in promoting the CICC, it will not be easy for the CICC to become a well-recognised and popular forum for international commercial disputes. It will not only face competition from various well-regarded counterparts but will also be challenged by its own structures and rules as well as the judicial system and social settings in China. Such challenges become particularly clear when the social and institutional issues discussed below are taken into consideration.

The neutrality of China's judges and judicial system may also be a concern for some international parties. Local governments may seek to influence court decisions in favour of their own interests, as represented by local litigants, State-owned enterprises (SOEs) under their control and local industry. This is commonly referred to as local protectionism, or administrative intervention. Corruption is another concern regarding China's public services system (including the judicial system in a broad sense). Although it has been suggested that judicial corruption at all levels is sporadic,Footnote 21 its negative impact is widespread. The Corruption Perceptions Index 2017 released by Transparency International showed that, despite some improvements in the past five years, China still ranked 77 among the 180 countries/regions sampled.Footnote 22 Influenced by these factors, the Chinese judicial system and legal environment have not been highly ranked either, which can be illustrated by the Global Competitiveness Index, considered below. These systemic problems may make the CICC a much less attractive forum.

Given such an unfavourable environment for the CICC's international competitiveness, China is now embarking upon massive reforms to improve the independence, efficiency and impartiality of its judicial system. Such reforms, as will be seen below, have had some promising outcomes and should be helpful for the future development of the CICC.

China has embarked upon a series of judicial reform measures to increase the capability and impartiality of judges. Since the publication of the White Paper on Judicial Reform in China in 2012, China has started its third round of judicial reforms since 1949,Footnote 23 all of which are on a significant scale. In October 2014, the CPC's Fourth Plenary Session of the Eighteenth Central Committee promulgated the ‘Decision of the CPC Central Committee on Major Issues Pertaining to Comprehensively Promoting the Rule of Law.Footnote 24 Further, on 9 April 2015, the CPC and State Council enacted ‘the Implementation Plan on Deepening the Judicial and Social System Decisions Made by the Fourth Plenary Session of the Eighteenth CPC Central Committee’. These reforms centralised court financing at provincial government level and this has alleviated concerns regarding the courts’ financial dependence on local governments. China also created six new circuit courts during 2015–2016. Aimed at avoiding local influences, these courts form part of the SPC and have the same level of jurisdiction as the SPC. China has also adopted extensive measures to increase the salaries and career prospects, as well as incentives, of judges.Footnote 25 In addition, it has made most court judgments (except judgments such as those involving State secrets, minor crime, divorce or custody of children) publicly available online (http://wenshu.court.gov.cn/) to increase the transparency of judicial activities.Footnote 26

It has been suggested that, despite the uncertainty as to whether the reforms will achieve significant success, these reforms move Chinese courts closer to genuine judicial independence.Footnote 27 This can be evidenced by the positive impact of such efforts on promoting the rule of law in China. According to the World Justice Project Rule of Law Index 2017–2018, China's respect for the rule of law has been improving.Footnote 28 Another important index, the Global Competitiveness Index by the World Economic Forum, has also shown that in the past three years China has made steady progress in the rule of law, its ranking among the sampled countries globally having been steadily increasing, as set out below.Footnote 29

Thus the CICC faces both opportunities and challenges as a result of China's suboptimal legal environment and the opportunities brought about by China's judicial reforms, as well as its growing economy and outbound investments.

III. THE FRAMEWORK OF THE CICC

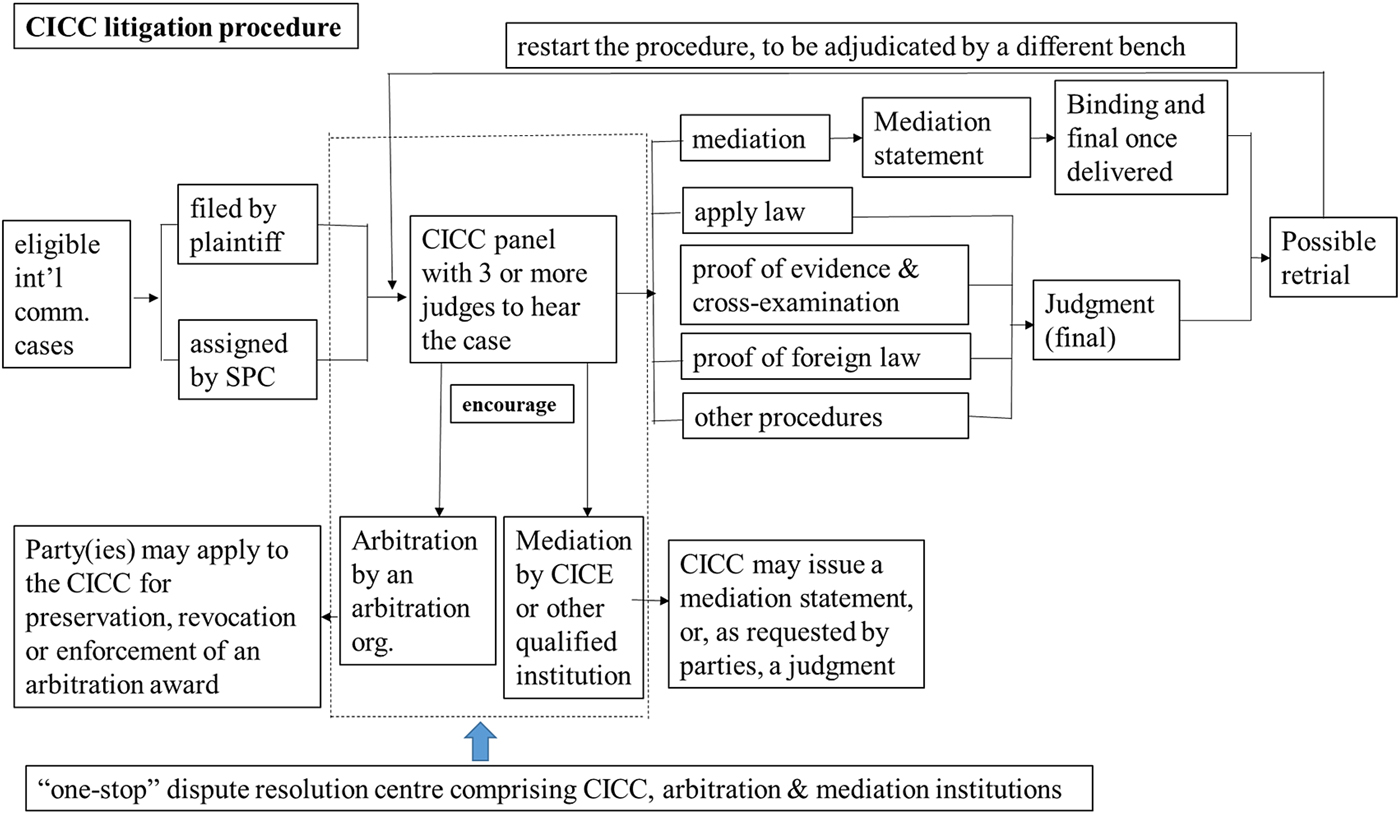

This section briefly introduces some unique mechanisms of the CICC when compared with the practices of other courts in China. The following Section IV provides a critical analysis of some key measures adopted by the Court's Regulations.

The CICC is part of the SPC.Footnote 30 By April 2019, the SPC had appointed 15 judges to the CICC. These judges were selected from among senior judges ‘who have extensive experience in trial work, are familiar with international treaties, practices and trade investment practices, and are proficient in both Chinese and English as working languages’,Footnote 31 thus resulting in some of the most experienced judges in China being appointed. The CICC has also established a Committee of International Commercial Experts (CICE), which (as at April 2019) comprised 31 world-renowned experts from various jurisdictions. Their key function is not to decide cases, but to provide advice on issues such as foreign law and to act as mediators.Footnote 32 The SPC also expects them to provide suggestions regarding amendments to the rules and the development of the CICC, as well as comment on the SPC's relevant judicial interpretations and judicial policies.Footnote 33

The cases brought before the CICC are heard by a collegiate panel consisting of three or more judges. The collegiate panel functions on the principle that the minority follows the majority (which implies that the number of judges in the panel must be odd), and minority opinions may be clearly stated in the judgment.Footnote 34 In cases adjudicated by other courts in China, it is a matter of controversy whether minority opinions can be included the judgment and the rules in this regard are unclear, and generally they are not included.

The CICC has simpler requirements regarding the admissibility of evidence generated outside the territory of mainland China compared with that adopted by other people's courts. It no longer requires such evidence to be notarised and certified, or to follow other certifying procedures that are required for other people's courts.Footnote 35 The CICC may also use audiovisual transmission technology and other information network methods to receive and cross-examine evidence.Footnote 36

Under the existing regulatory regime in China, if documents and other materials in a foreign language(s) are submitted to a people's court, a translation in Chinese must be provided.Footnote 37 However, for cases heard by the CICC, if the evidence submitted by one party is in English (but not other languages) and the other party agrees that translation into Chinese is not needed, then this will not be required.Footnote 38 However, such evidence is subject to cross-examination in court.Footnote 39

As the CICC is part of the SPC, which has the highest judicial power in China, it has greater enforcement powers than other Chinese courts. This is reflected in Article 6 of the Regulations, which provides that the CICC may designate a lower-level people's court (including all local people's courts and special people's courts under the jurisdiction of SPC, as explained above) to enforce an asset preservation ruling that it has made.

The Regulations do not make provision for either the enforcement of its judgments by courts in foreign jurisdictions or the enforcement of foreign judgments. Although China signed the Hague Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters in July 2019,Footnote 40 until ratification it will still rely on the general provision in the Civil Procedure Law (CPL) for recognising and enforcing foreign judgmentsFootnote 41 and on various bilateral judicial assistance treaties concerning the enforcement of foreign judgments.Footnote 42

It is noteworthy that, as a newly established organisation, the CICC has placed much emphasis on the informatisation of its operation. It has established an electronic litigation service platform, a trial process information disclosure platform and other litigation service platforms. Various tasks, such as filing, payment, file review, evidence exchange, delivery and court hearings can also be done through these information networks.Footnote 43

In addition to these cost-effective mechanisms for disputants, the CICC has adopted some other innovative practices that go further than those of other people's courts in China. For example, the one-stop dispute resolution hub (comprising mediation, arbitration and CICC) that the CICC is endeavouring to develop provides significant convenience to the parties involved in mediation and arbitration, because the parties concerned can apply to the CICC for arbitration preservation during arbitration or for the revocation or implementation of an international commercial arbitration award.

IV. HOW FAR HAS THE CICC GONE?

Despite its innovations and conveniences, when compared with the practices of some overseas counterparts, the rules adopted by the CICC are conservative. The following sections analyse such measures from a theoretical and comparative perspective. Of course, it is necessary to emphasise that, unlike some overseas counterparts that have revised the statutory framework or constitution or enacted new laws to overcome statutory or constitutional impediments, the CICC was established without an extensive preparation period and thus statutory impediments have not been effectively addressed. There is no doubt that the CICC, as a part of the Chinese judicial system, will need to operate within the existing general legal framework.

A. Judges

Judges play a core role in the operation of courts, including managing cases and making decisions. In the context of international commercial dispute resolution, it is possible that one party will believe that the other party's national court will not be neutral no matter how well the particular court performs.Footnote 44 However, well-regarded international judges can alleviate such concerns and boost the confidence of the parties concerned, because it is believed that international judges will be less influenced by the interests of the nation where the court is located. At the same time, international judges may provide expertise in foreign commercial law. A balanced international composition of the judicial bench can ensure they have a good understanding of the commercial world globally, rather than just domestically. Thus, the appointment of international judges is perceived to be of benefit for international commercial courts.Footnote 45

As noted by the Honourable Chief Justice Marilyn Warren AC and the Honourable Justice Clyde Croft in Australia, ‘successful international commercial courts must be inherently outward looking, and adapt their processes to the changing needs and expectations of the international market’.Footnote 46 Internationalisation is strongly reinforced by international judges, who can help to improve the competitiveness of such courts. Even in other jurisdictions that already have a good international reputation (such as Australia), the possibility of establishing international commercial courts and appointing foreign judges has been discussed.Footnote 47

The following chart shows the international composition of four major international commercial courts (up to April 2019). From this chart, it can be seen that the appointment of international judges from other jurisdictions has become a standard and distinctive practice of these international commercial courts. In particular, most of them are trained in the English common law system.

English common law plays a leading role in global commercial dispute resolution. As noted by Richard Southwell, its success lies in three key factors: the calibre and experience of the judges, its relatively informal and flexible procedure, and a cohort of specialised solicitors and barristers. All of these factors increase the efficiency and speed of dispute resolution and therefore reduce the costs to the parties concerned.Footnote 48 Given the significance of English common law in this regard, common law jurisdictions have been established to support international financial centres located within non-common law states and English has been chosen as the working language of the international commercial courts.

For example, the DIFC is a purpose-built English language common law jurisdiction. It aims to adopt a regulatory regime to provide global businesses with a familiar environment that is governed by financial laws and regulations substantially similar to those practised in leading common law countries.Footnote 49 As such, the DIFC Courts are ‘based substantially on English law in codified form but with civil law influence’,Footnote 50 and are ‘independent from, but complementary to, the UAE's Arabic-language civil law judicial system and arbitration centres’.Footnote 51 The ADGM Courts and their judiciary are also broadly modelled on the English judicial system. English common law (including the rules and principles of equity) is directly applicable in the ADGM and is the foundation of its regulations. Moreover, a wide range of well-established English statutes (including those drawn from Australian Federal law) are also applicable in the ADGM.Footnote 52 The Astana International Financial Centre (AIFC) Court established in the Republic of Kazakhstan is also a common law court, which is separate from the legal system of Kazakhstan.Footnote 53

The dominance of English common law in global commercial dispute resolution raises the question whether China should borrow more investor-friendly procedures and practices from English common law, and if possible, appoint some judges with a common-law background who may be more familiar with global business and dispute resolution practices to complement the existing domestic judges. In China, the CICC has no ‘international’ judges and all judges are Chinese citizens. Although the judges appointed to the CICC are well-regarded senior judges, the diversity of their background is still not significant given the wide range of issues and cases that may be adjudicated before it. This may decrease the competitiveness of the CICC as a forum for the international business community. As noted above, international judges can also help to alleviate the possible concerns of foreign parties regarding the neutrality of Chinese domestic judges and help the CICC to have a better understanding of global business rules and their development.

The Chinese authorities appear to have realised this potential weakness. To fill this ‘internationalisation’ gap, the CICC has established the CICE which is comprised of experienced international experts. This is a significant innovation, given the complexity of business and the necessity for ‘judges’ to be well informed regarding the latest developments in global business. The success of the London Commercial Courts illustrates the importance of having experts in the various areas of business in which it works. As Lord Chief Justice John Thomas explained, ‘London has a historic advantage. In the 18th Century Lord Mansfield, the creator of the basis of modern English commercial and insurance law, often used special juries drawn from experts in the field: being, for instance, commercial merchants, insurance brokers, traders and so on. Their expertise would be practical expertise.’Footnote 54 At the same time, if the parties before the CICC accept mediation by the CICE, they may still apply for a CICC judgment based on the mediation outcome.Footnote 55 Thus, the experts in the CICE are able to ‘make decisions’ indirectly via the mechanism of mediation. Given the short history of the CICE, the significance of the role of the members of the CICE remains to be seen.

In short, international commercial courts should embody features of internationalisation. It is desirable for the CICC to have a more diverse composition of judges (including international judges from different jurisdictions).Footnote 56 However, there are certain statutory impediments to doing so, which are considered in Part V below.

B. Choice of Forum

1. The criteria of an international commercial case

Five case categories fall under the CICC's jurisdiction: (1) first instance cases in which the parties have chosen the jurisdiction of the SPC through a choice of court agreement pursuant to Article 34 of the Civil Procedure Law with an amount in dispute of at least 300,000,000 Chinese yuan; (2) first instance cases transferred by a high people's court and approved by the SPC; (3) first instance cases having a significant national impact (as decided by the SPC); (4) cases involving applications for arbitration preservation, revocation or implementation of an international commercial arbitration award(s); and (5) cases falling into a catch-all category; namely, other cases that the SPC considers should be heard and tried by the CICC.Footnote 57 In short, the cases can be placed into two broad categories: cases as decided by the parties (subject to some restrictions as analysed below) and cases as decided by the SPC.

The Regulations clearly define an ‘international commercial case’. If a case falls into one of the following four categories, then it is considered to be an ‘international commercial case’:

(1) One or both parties are foreigners, stateless persons, foreign enterprises or organisations;

(2) The permanent residence of one or both parties is outside the territory of the People's Republic of China;

(3) The subject matter is outside the territory of the People's Republic of China;

(4) The legal facts concerning the creation, alteration or elimination of commercial relations occur outside the territory of the People's Republic of China.Footnote 58

The CICC does not have the jurisdiction to deal with cases in which one or both parties are sovereign states as such disputes are dealt with by the dispute resolution mechanisms provided for in the bilateral investment treaties that China has entered into with other states.

In some international conventions, such as the United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (1980) and the Convention of 22 December 1986 on the Law Applicable to Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (not yet in force), the benchmark for assessing ‘international’ in international sale of goods is relatively simple.Footnote 59 The two conventions above also exclude certain sales from the definition of ‘international sale of goods’.Footnote 60 Compared with this, the definition of international commercial case in the Regulations (and the existing Chinese legal system) is broader.Footnote 61 However, many cases classified as ‘international commercial cases’ under the Regulations may actually be domestic cases. For example, under Article 3(1) and (2), the definition will be satisfied where a non-Chinese citizen or enterprise (or a Chinese citizen whose permanent residence is outside China) signs a commercial contract in China with another Chinese entity, and where all other elements occurred in China. This case is better conceptualised as a domestic case as it has no foreign element except that at least one of the parties is non-Chinese. Further, under Article 3(4), two Chinese citizens may purposely sign a purely domestic commercial contract in various other jurisdictions (eg, Hong Kong, Macau or Singapore) and thus create an ‘international commercial case’.

Whether a commercial case is classified as domestic or international is significant in the context of China's litigation system. The CICC only has jurisdiction over eligible international commercial cases, and not over domestic cases. In relation to the choice of law, for purely domestic cases, generally only PRC law can be chosen; while for cases with a foreign element, foreign law and applicable international conventions or treaties may be chosen. In addition, Chinese authorities are generally more cautious in dealing with foreign-related cases than purely domestic ones.

In addition, if any party intentionally creates ‘international commercial case’ factors in order to meet the jurisdiction requirement of the CICC, the other party may claim that this was done in circumvention of mandatory law and is invalid. The legal treatment of such a claim is uncertain and gives rise to complex issues. In the context of the CICC, given its convenience for the parties concerned, the expectation that costs will be relatively lower and its procedures more efficient, some parties may introduce a foreign-related factor for the purpose of falling within the jurisdiction of the CICC. In practice, there have been cases in which disputes have arisen regarding the question of whether a case is domestic or foreign-related and the courts have issued conflicting opinions regarding the nature of cases with such elements.Footnote 62 In short, this is an unsettled issue and is subject to the broad civil procedural rules in China. Overall, the rules or criteria regarding the SPC's exercise of its discretion on the jurisdiction of the CICC are still very unclear,Footnote 63 and the practice of the CICC regarding the understanding and application of the categories of international commercial cases remains to be seen. It will be important for the judges of the CICC to exercise discretion to assess the eligibility of a case for the jurisdiction of the CICC, as in other international commercial courts.Footnote 64

2. The requirement for cases to have a connection with China

As outlined above, Article 2(1) of the Regulations provides that the CICC has jurisdiction over first instance cases in which the parties have chosen the jurisdiction of the SPC through a choice of court agreement pursuant to Article 34 of the Civil Procedure Law with an amount in dispute of at least 300,000,000 Chinese yuan. Article 34 of the CPL stipulates that:

The parties to a contract or other property rights dispute may, in written agreement, choose the jurisdiction of a people's court in a place where the defendant resides, the contract is executed, the contract is signed, the plaintiff resides, the subject matter is located, etc., or other places where the dispute has actual connection(s). Such a choice should not violate the stipulations regarding level jurisdiction and exclusive jurisdiction in this law.

Pursuant to this provision, the choice of court agreement should be in written form, and the case to be heard by the CICC should have an actual connection with China.

Traditionally, under private international law, jurisdiction of international litigation has been based on consent, ‘personal connections’ with the forum, and mostly a specific connection with the territory of the state, which in a narrow sense requires a ‘physical connection’ with the territory (such as domicile or the place of the tort).Footnote 65 However, with globalisation, in particular e-commerce, the traditional requirement of physical connection with the territory has been brought into question.Footnote 66

The argument to abolish such a requirement has been supported by various studies.Footnote 67 Most countries recognise the effectiveness of an exclusive jurisdiction clause in civil and commercial matters as agreed by the parties concerned.Footnote 68 In English common law, generally, so long as the choice of forum is bona fide and is not against public policy, such a choice should be upheld even where there is no connection with England.Footnote 69 Many civil law jurisdictions do not have a requirement for a connection with the jurisdiction either.Footnote 70 As such, so long as the choice of forum is not contradictory to public policy or an evasion of mandatory rules of the jurisdiction with which the contract is most substantially connected, it is generally permitted.Footnote 71 Representative international conventions, such as Article 5 of Hague Convention on Choice of Court Agreements, which China has signed but not yet ratified, and Article 23 of EU Council Regulation (EC) No 44/2001 of 22 December 2000 on Jurisdiction and the Recognition and Enforcement of Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters, do not impose a requirement for a connection with the jurisdiction on a choice of court agreement.

The international commercial courts generally do not require a connection between the parties or transactions and the jurisdiction in which the chosen court is located. The SICC, for example, requires neither the parties nor the subject matter of the dispute under its jurisdiction to have a connection with Singapore. In particular, the applicable rules specifically state that ‘the Court must not decline to assume jurisdiction in an action solely on the ground that the dispute between the parties is connected to a jurisdiction other than Singapore, if there is a written jurisdiction agreement between the parties.’Footnote 72 The DIFC Courts and ADGM Courts adopt a similar principle.Footnote 73 An exception is the Qatar International Court.Footnote 74 At present, the underlying legislation that provides for the jurisdiction of this Court requires at least one party to the dispute to have an affiliation, in accordance with the provisions of the Article 8(3)(c) of QFC Law No 7 of 2005 (as amended), with the QFC. However, it appears likely that such a position may change in the near future to allow a party who has no connection with the QFC to opt into the jurisdiction of the Court.Footnote 75

In China, the requirement for a connecting factor in the choice of forum as stipulated by Article 2(1) of the Regulations is consistent with the 2017 CPL, Article 265.Footnote 76 A similar requirement for a connection with the jurisdiction applies in relation to the recognition by Chinese law of the choice of foreign courts under Article 531 of the Supreme People's Court Judicial Interpretation of the Application of the Civil Procedure Law of the People's Republic of China (2015 Judicial Interpretation of the CPL).Footnote 77 Accordingly, Chinese law requires a Chinese court chosen by the parties to be connected with the disputes or parties (no matter whether it concerns a purely domestic case or a foreign-related case). An exception is that Chinese law allows the Chinese maritime court to assume jurisdiction over cases that have no connection with China.Footnote 78 Chinese law also requires a foreign court to have such a connection before it will recognise the choice of the foreign court by the parties.Footnote 79 This may result in a Chinese court accepting jurisdiction over a dispute in circumstances where the parties have submitted to the exclusive jurisdiction of a foreign court.

Such a connecting factor requirement is controversial. As it applies to the choice of foreign courts, Professor Tu has commented that ‘Chinese ‘‘jurisdiction by connection’’ can be said to be a unique international jurisdictional ground which, one might be able to predict, could, indeed, be quite broad and even exorbitant in practice.’Footnote 80 The most commonly used reason to support such a broad approach is the concern that a stronger party may force the other to enter a jurisdiction agreement by fraud, coercion, abuse of economic power, or other improper means, which may lead to the circumvention of the law and/or damage to the interests of the weaker party.Footnote 81

This argument is particularly relevant where Chinese parties may be in a disadvantaged position in disputes arising from their overseas investments.Footnote 82 The China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (CCPIT, a trade body of the Chinese government founded in 1952, also named the China Chamber of International Commerce) has revealed that more than 90 per cent of foreign-related contracts signed by Chinese enterprises have agreed to resolve disputes through arbitration; 90 per cent of them have chosen foreign arbitration institutions; and the Chinese enterprises' have lost more than 90 per cent of such cases.Footnote 83 Thus the supporters of this argument believe that China is at a disadvantaged position in the global competition for jurisdiction and thus the requirement for connecting factors to justify jurisdiction should be upheld.Footnote 84

However, it appears that there is a stronger argument among Chinese academics that the use of connecting factors to justify jurisdiction should be discarded. Reasons suggested by existing studies include the following: (1) it deprives the parties of the right to choose a neutral court—the choice of a neutral count is essential for international business when the parties are not able to reach a consensus regarding the choice of forum because each party is concerned about the possible bias of the courts in the other party's State;Footnote 85 (2) it excludes the jurisdiction of Chinese courts in cases involving foreign parties where the parties have chosen the jurisdiction of a Chinese court (eg the CICC) as the forum court but no connecting factors exist;Footnote 86 and (3) Chinese law should respect the autonomy and choice of the parties concerned, and abandon such a requirement in line with the global trend.Footnote 87 In line with these studies, this article supports the abolition of such a requirement.

Various reasons can be given in support of this position. First, Chinese law has already provided a very broad definition of ‘connecting factors’. Article 34 of the 2017 CPL provides that ‘the parties to a contract or other property rights dispute may, in written agreement, choose the jurisdiction of a people's court in a place where the defendant resides, the contract is executed, the contract is signed, the plaintiff resides, the subject matter is located, etc., or other places where the dispute has actual connection(s)’. Here the reference to ‘etc.’ theoretically provides unlimited choices for the parties concerned.Footnote 88 In practice, the Chinese courts have differing understandings and inconsistent practices concerning the enforcement of the ‘connection requirement’.Footnote 89 If there is no coercion by one party of the other party, an overseas jurisdiction where the non-Chinese plaintiff/defendant's domicile is located may be recognised as the forum.

In the international business context, Chinese law allows the parties to choose a foreign court as the exclusive forum court (so long as it has such ‘connecting factors’) for most foreign-related commercial cases.Footnote 90 As noted by previous research, it would be overly simplistic if a binary division between exclusive and non-exclusive choice of court is adopted, given the complexity of jurisdiction agreements in commercial life.Footnote 91 Chinese law currently permits non-exclusive choice of courts.Footnote 92 The issues regarding exclusive or non-exclusive choice of courts are related to, but are not the focus of, this article and thus are introduced here but not further analysed. In practice, the parties may sign the contract in the jurisdiction where they intend to choose the court to satisfy the connection requirement and circumvent the restriction that would otherwise apply. These practices may make the perceived protection of the weaker party (on many occasions the Chinese party) something that exists only in name.

Moreover, if the parties really do not like to be restricted by the connecting factors in their choice of court, they may turn to arbitration, which has no such requirement.Footnote 93 In reality, the data published by CCPIT not only shows the possible disadvantaged position of the Chinese parties in the global business dispute resolution, but also the fact that the connecting factors requirement in Chinese law cannot successfully achieve its purpose of protecting Chinese parties against such disadvantages. In short, there are various methods to circumvent or exclude the jurisdiction of Chinese courts, and therefore using jurisdiction to protect Chinese parties cannot be well justified.

Secondly, Chinese law allows the parties to a foreign-related contract to choose foreign law as the governing law, even where the relevant foreign jurisdiction has no connection with the dispute or the parties concerned.Footnote 94 If the parties choose foreign law as the applicable law, but commence litigation in a different jurisdiction because of the connection requirement, it would lead to concerns regarding how to prove foreign law and the enforcement of a foreign judgment. This is not only a process that is time-consuming and resource-intensive; it may also create obstacles for the recognition and enforcement of a State's judgment in another State where the assets are located. It is argued that only the parties to the contract know the best choice of law and forum for them to manage such concerns and thus party autonomy should be permitted by Chinese law.

Thirdly, as suggested before, China's acceptance of maritime cases without a connection with China has already provided a good example of discarding such a connection requirement. This principle can also be applied to the CICC, as its institutional settings and functions are different from other people's courts. From a global perspective, various countries have adopted significant innovations to break the constitutional barriers of jurisdiction of this kind. For China, as illustrated in Part II, the CICC is already in a disadvantaged position in terms of its competitiveness compared with its counterparts given China's unique institutional settings. Such a connection requirement would exclude some cases without such connections and put the CICC in an even worse position in terms of its competitiveness, as fewer parties would choose the CICC as the forum court. Thus, it is also desirable to enable the CICC to expand its jurisdiction.

In short, allowing party autonomy to choose the forum court would be the most desirable approach. As to certain problems (such as circumvention of mandatory law, fraud or the use of coercion or abuse of economic power or other improper means to choose the jurisdiction that puts the weaker party at a disadvantaged position) that may arise from abandoning this requirement, it is suggested that they can be examined and alleviated by the court following certain principles such as the principle of bona fides and the principle that the choice of forum should not be against public policy or circumvent mandatory law. Moreover, China can use the CICC as a pilot programme to hear and try cases that have no connecting factors with China. Therefore, the CICC could achieve innovation by abandoning the connection requirement, using this development to test its impact on the judicial system generally, and gain insights for future reforms.

3. Forum non conveniens

Another issue that may be relevant in the case of the CICC is the doctrine of forum non conveniens, which has been de facto applied by some Chinese courts since the 1990s.Footnote 95 This doctrine has been largely developed by the Chinese judges, who have paid close attention to procedural efficiency and justice as well as international comity between countries, instead of relying solely on written law.Footnote 96 In 2015, Article 532 of Judicial Interpretation of the CPL formally established this doctrine. According to this judicial interpretation, the doctrine of forum non conveniens can be applied by a Chinese court to dismiss a foreign related civil or commercial case if the following conditions are fulfilled:

(1) the defendant suggests that the case should be subject to the jurisdiction of a foreign convenient court, or raises an objection regarding jurisdiction of the Chinese court;

(2) there is no choice of court agreement between the parties to choose the (Chinese) court as a forum court;

(3) the case is not subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the court in China;

(4) the case does not involve the interests of the Chinese citizens, legal persons or other organisations;

(5) the main facts leading to the dispute(s) did not occur in China, nor did the case use Chinese law as the applicable law, (as a result) the Chinese court(s) would have difficulties in determining facts and applying laws if it accepted the case; and

(6) the foreign court has jurisdiction over the case and it is more convenient for it to hear the case.

There are many conditions restricting the use of this doctrine in Chinese courts. If the parties choose a Chinese court (including the CICC) with a choice of court agreement and such an agreement is valid under Chinese law (as in the context of Article 2(1) of the Regulations), this doctrine would not be applicable. For other cases assigned by the SPC to the CICC, this doctrine would not be applicable either, as the SPC would assess the suitability of this case for the CICC before transferring it.

C. Determining Foreign Law

As to the governing law for the cases heard by the CICC, if the parties choose the governing law in accordance with relevant Chinese law, the law chosen by the parties is to be applied.Footnote 97 Like other courts in China, the CICC can hear cases where foreign law has been chosen as the governing law.Footnote 98 Pursuant to Article 7 of the Regulations, if the parties do not choose the governing law, the CICC will determine the substantive law governing the dispute in accordance with the Law of the PRC on the Application of Laws to Foreign-Related Civil Relations.

Article 8 of the Regulations concerns the determination of foreign law by the CICC. The question of how foreign law is determined is of critical importance for the legal system in every jurisdiction. The approach differs between common law and civil law jurisdictions.

A key point in relation to common law jurisdictions is that the content of foreign law is considered to be a matter of fact and not a matter of law.Footnote 99 Accordingly, as courts and judges are deemed to have no knowledge of facts, the content of foreign law must be proved by the parties. The onus of proving foreign law is on the party who seeks to rely on it.

Further, unless the content of the foreign law is admitted by the other party, the party who seeks to rely on foreign law must call a foreign law expert to provide evidence. This is because a party cannot prove foreign law simply by providing the court with materials such as legislation and case law. Instead, the evidence of a foreign law expert is required to explain and interpret such materials.

Although the court will decide whether to accept or reject the evidence of a foreign law expert and the potentially conflicting evidence of a foreign law expert called by the other party, the court will not conduct its own research to determine the content of foreign law. This reflects the adversarial principle in common law jurisdictions, where the role of the court is to determine the facts of the dispute on the basis of the submissions made by the parties and as proved by the parties. Unlike the courts in civil law jurisdictions, the common law courts are not inquisitorial in nature; in other words, they do not undertake their own investigations to determine the facts. As a general rule, a common law court will not make its own investigations to determine the content of foreign law. It is only where the expert evidence is obviously incorrect that a court can look at the relevant sources of foreign law to determine its content.

Because the content of foreign law is considered to be a question of fact, it is the choice of each party to the dispute as to whether to plead or rely on the foreign law in support of its case. There may be various reasons why a party may choose not to plead foreign law, even though it would otherwise be applicable. For example, the position under the foreign law may not be favourable to the party's case. In addition, the party may decide that the benefits of pleading foreign law are outweighed by the cost of calling expert witnesses and the uncertainty as to whether the expert evidence will be accepted by the court.

Where a party fails to plead the content of foreign law or the expert evidence provided by the party is not accepted by the court, the traditional principle in common law jurisdictions is that the court will presume that the foreign law is the same as the lex fori (ie the law of its own jurisdiction) and apply the lex fori. The presumption that foreign law is the same as the local law has been criticised by many judges and scholars on the basis that it is artificial. An alternative explanation is that if foreign law is not proved, the lex fori will apply by default. This approach is closer to the approach in civil law jurisdictions.

Although foreign law is treated as a question of fact in common law jurisdictions, it is possible for appellate courts to overrule a judgment of a lower court on the basis that the foreign law had not been applied correctly. This is different from the general rule that findings of fact cannot be challenged on appeal.

There are two situations in which it is not necessary for a party to prove foreign law. The first is where the court is considered to have knowledge or ‘judicial notice’ of the law in the other jurisdiction. This situation often arises in federal systems such as Australia, where the courts in one state are considered to have judicial notice of the legislation in another state. The second situation arises where arrangements are in place for the court to refer questions of foreign law to the judges in the foreign jurisdiction. For example, the Supreme Court of New South Wales in Australia has entered into agreements with the Supreme Court of Singapore and the New York courts to refer questions of law to judges in those jurisdictions for determination. A similar arrangement is in place between the Member States of the European Union.

By contrast, the position in many civil law jurisdictions is that the content of foreign law is considered to be a question of law and not a question of fact.Footnote 100 In addition, consistent with the principle that the court knows the law (as reflected in the Latin phrase iura novit curia), the parties to a dispute do not need to prove the foreign law. Instead, the courts apply the law ex officio; namely, they apply the law by virtue of their status as a court of law. As a result, if a matter in the dispute is governed by foreign law, the court must apply the foreign law, whether or not it has been pleaded by the parties to the dispute. In addition, if the court does not have sufficient knowledge of the foreign law, it must ascertain the foreign law itself, either on the basis of its own investigation or on the basis of evidence provided by the parties.

Article 10 of the Law of the PRC on Application of Laws to Foreign-Related Civil Relations provides as follows:

The foreign law applicable to foreign-related civil relations shall be determined by the people's court, arbitral body or administrative organ. Any party who chooses to apply the law of a foreign country must provide the law of that country.

If the law of the foreign country cannot be determined or the law of that country does not make provision, the law of the People's Republic of China shall apply.

Prior to the above provision, it was uncertain how foreign law should be determined in Chinese courts and whether it should be proved as a matter of fact or determined by the court ex officio. It is now clear that it should be determined by the court on the basis of submissions by the parties and that there is no requirement for the parties to prove it through expert evidence. This brings China's approach into line with the general approach in civil law jurisdictions as outlined above.

The Singapore International Commercial Court represents an interesting departure from the traditional common law approach. There is no requirement for foreign law to be proved. Instead, the court may determine foreign law on the basis of submissions from the parties. As a result, the parties to disputes before the court do not need to call foreign law experts to prove the foreign law. Of particular interest is Rule 26(4), which provides that in addition to considering the parties’ submissions, the Singapore International Commercial Court may have regard to a broad range of sources in determining the foreign law. These include the legislation and case law in the foreign country.Footnote 101 It is perhaps in this respect that the approach of the Singapore International Commercial Court departs most radically from the traditional common law approach, under which courts were deemed to have no knowledge of foreign law and, consequently, foreign law had to be proved by experts.

Article 8 of the Regulations sets out a broad range of means by which the CICC may determine foreign law, including on the basis of submissions by the parties, legal experts and members of the CICE. Article 8 further provides that ‘the materials and expert opinions on foreign law provided in one or more of the above ways shall be presented during the hearing in accordance with the law and the parties shall be afforded a full opportunity to be heard.’ Although this provides each party with an opportunity to be heard in the event that there is a disagreement as to the interpretation and application of the foreign law in question, it does not state expressly how such a disagreement should be resolved by the CICC. The most likely outcome is that the court will apply PRC law by default under Article 10 of the Law of the PRC on Application of Laws to Foreign-Related Civil Relations, as extracted above. The uncertainty concerning the determination of foreign law reinforces the benefits of appointing to the bench of an international commercial court foreign judges who are conversant in the laws of their jurisdiction and are in an authoritative position to determine foreign law in the event that there is a difference of opinion between the parties or an inconsistency in the materials and expert opinions that are submitted for the purpose of determining foreign law.

D. An Emphasis on Mediation

The CICC aims actively to cultivate and improve diversified dispute resolution mechanisms for international commercial litigation, mediation and arbitration, as well as to resolve international commercial disputes effectively and meet the diversified needs of dispute resolution for both Chinese and foreign parties.Footnote 102 Thus, the CICC will also cooperate with selected qualified international commercial mediation agencies and international commercial arbitration institutions to jointly establish a dispute resolution hub. So far, the CICC has included seven arbitration/mediation institutions in this hub. Such a dispute resolution legal service hub comprises functions of mediation, arbitration and litigation, aimed at facilitating the multiple methods of dispute resolution at the choice of the parties concerned and creating a ‘one-stop’ international commercial dispute resolution mechanism.Footnote 103

As to the mediation procedures, within seven days of accepting a case, the CICC may, with the consent of the parties, entrust a member of the CICE or an international commercial mediation agency to mediate the case.Footnote 104 If a mediation agreement is reached, the CICC may issue a mediation letter in accordance with the law. A mediation statement has the same effect as a judgment after it has been signed by both parties.Footnote 105 If the parties request a judgment, the CICC may also make a judgment according to the content of the mediation agreement and deliver it to the parties concerned.Footnote 106

The Regulations do not expressly provide that the judges themselves may act as mediators. It is not clear whether the reference to a ‘mediation statement made by the CICC’ in paragraph two of Article 15 includes a statement made by the judges acting as mediators or simply refers to the procedures of Article 13 for converting the mediation agreement into a mediation statement in the context of an application submitted by the parties concerned. In other people's courts in China, judge(s) may act as the mediator(s), although other people may also be invited to act as mediators.Footnote 107 Article 94 of the 2017 CPL provides as follows:

When a people's court conducts mediation, mediation may be conducted by one judge or by the collegial bench, and mediation shall be conducted in situ to the extent possible.

In addition, the SPC has issued several guidance notices on judicial mediation. The latest guidance is contained in the 2010 Notice on Issuing Several Opinions on Further Implementing the Work Principle of ‘Giving Priority to Mediation and Combining Mediation with Judgment’.Footnote 108

Article 2 of the Notice requires courts in China to give priority to mediation at all stages during the court process, including before and after the commencement of litigation. The Notice provides in Article 3 that during the course of hearing a case, the court must first consider whether mediation should be used to resolve the case. Where there is a possibility of mediation, mediation should be undertaken to the extent possible. Article 11 provides that the mediator may be selected jointly by the parties and may also be nominated by the court with the consent of the parties.

Article 67 of the 2001 Certain Provisions of the Supreme People's Court Concerning Evidence in Civil ProcedureFootnote 109 provides that any admission of fact made during mediation for the purpose of agreeing a mediation agreement or reaching a settlement may not be used as unfavourable evidence in any subsequent proceedings. Accordingly, judges who act as mediators are required to maintain the confidentiality of matters discussed during the course of mediation.

In many cases in other people's courts in China, the judge who is hearing a case also acts as a mediator. Further, when acting as mediators, judges often adopt an evaluative approach to mediation. Under this approach, the judge evaluates the legal issues in the case and actively presents strategies to the parties for resolving the dispute. This approach can be contrasted with facilitative mediation, under which the mediator adopts a neutral role and focuses more on facilitating negotiations between the parties than actively presenting strategies for the parties to consider.Footnote 110 In English, the former approach is often referred to as ‘conciliation’ and the latter approach is referred to as ‘mediation’.

In certain civil law jurisdictions, such as Switzerland and Germany, judges are actively involved in mediation and often act as mediators in the same case in which they are sitting as a judge. In other civil law jurisdictions, such as France, judges are rarely involved in mediation.

Similar to the position in China, mediation is now recognised as an important alternative to court adjudication in common law jurisdictions and is increasingly effective in helping to resolve disputes in civil proceedings. Common law jurisdictions diverge, however, on the question of whether current judges should act as mediators.Footnote 111 Although most people would agree that retired judges should be able to act as mediators if they are appropriately trained, many people argue that current judges should not act as mediators. Several reasons are given for this argument. First, judges acting as mediators may get involved in the process that is called ‘caucusing’, under which the judge meets separately with each party or their legal representatives. Such practice may be inconsistent with the adjudicative role of a judge and breach the statutory or constitutional requirements in the relevant jurisdiction. Secondly, there is a risk that a judge will express an opinion on the legal issues or the final outcome, which would undermine the principles of mediation.

Thirdly, it is argued that judges should not get involved in private dispute resolution as their role in the justice system is to hear public disputes and to maintain the transparency of judicial proceedings and public confidence in the courts. Finally, if judges act as mediators, they need to be trained as mediators and most judges have not received such training.

On the other hand, many people argue that there are good reasons as to why current judges should act as mediators. These include the argument that if judges do not broaden their role to include acting as mediators in a non-adversarial context, there is a risk that the courts will become less relevant and that they will be seen as a form of alternative dispute resolution instead of as the mainstream forum for resolving disputes. In addition, many people argue that judges can be trained as mediators and that they have unique skills in identifying and helping to resolve issues.

Although there is a lack of consensus as to whether current judges should act as mediators, common law jurisdictions are consistent in rejecting the proposition that the judge who is hearing a case should act as a mediator in the same case. The main argument against this proposition is that a judge who has acted as a mediator between the parties will not be perceived to be impartial if the mediation is unsuccessful and the judge is required to determine the issues. This is because the judge may have heard admissions by one or both parties during the course of the mediation and it is unrealistic to expect that the judge can ignore such prejudicial evidence when adjudicating the case.

It is possible that the SPC decided against expressly permitting judges of the CICC to act as mediators as a result of the ongoing debate in many jurisdictions as to whether judges should act as mediators. But this question needs to be further clarified by the SPC.

E. One Trial to Conclude a Case and the Finality of Judgments

The appellate mechanism (and the absence of such a mechanism in arbitration) is an important factor that has led to the rise of international commercial courts. As Menon CJ has noted, ‘certain cases are better suited for a process that is relatively open and transparent, equipped with appellate mechanisms, the options of consolidation and joinder, and the assurance of a court judgment.’Footnote 112 The international commercial courts globally adopt the appellate mechanism to enable parties to appeal a decision except where they have agreed otherwise.

However, the CICC adopts a regime of one trial to conclude a case. One rationale behind such a regime is that the CICC is a branch of the SPC, whose judgments are final and binding.Footnote 113 This principle is also applied to the cases where the SPC hears a trial of first instance.Footnote 114 Another rationale is that one trial can improve efficiency, convenience, and cost-effectiveness.Footnote 115

As previously noted, if the parties concerned have signed the mediation statement made by the CICC, the mediation statement has the same legal effect as a judgment made by the CICC.Footnote 116 In a literal sense at least, it is unclear from the provisions of Articles 15 and 16 of the Regulations whether, if the parties have reached a mediation agreement under the supervision of the CICE or another recognised mediation institution but have not applied for a mediation statement from the CICC, such an agreement will have the same legal force as a judgment made by the CICC for the purpose of applying for enforcement by the CICC. If not, it would simply have contractual effect between the two parties.

However, the Regulations do not specify the legal force of the mediation statement if one or both sides refuses to sign such a statement and reneges on the agreement. The legal force of the mediation statement made by the court but refused by the parties before it is delivered is unclear under existing Chinese law. Pursuant to Article 97 of 2017 CPL, once both the parties concerned have signed the mediation statement made by a people's court, the mediation statement comes into force. Article 99 of the 2017 CPL further stipulates that if one party goes back on the mediation statement before it is delivered, the people's court must make a timely judgment (as the mediation statement is deemed ineffective in this context). This means that the CPL allows the parties to renege on the mediation statement before it is formally delivered to them. However, there are some cases (such as those relating to marriage and adoption, those that can be performed immediately and those that by their nature do not need a mediation statement) where a mediation statement is unnecessary, and therefore the parties are not allowed to renege on the mediation agreement as the mediation agreement has become binding and effective once it is officially made.Footnote 117

Given the nature and significance of the cases that may be heard by the CICC, even if the disputes are settled by mediation, it is better for the parties to request a mediation statement or judgment from the CICC. Such an approach not only avoids the legal uncertainty in the unlikely but still possible situation that one side reneges on the mediation outcome; it also provides a basis on which to apply for enforcement, particularly in other jurisdictions.

An appeal in common law jurisdictions generally is limited to appeals on points of law. In China, however, there is no substantial restriction on the right of appeal. So long as one party is dissatisfied with the judgment, he/she is entitled to initiate the appeal proceedings pursuant to Article 164 of 2017 CPL. Although the judgment made by the CICC (and the SPC) is technically final and binding, such a ‘final’ judgment made in this one trial system is subject to a possible retrial pursuant to Chapter 16 ‘Procedure of Trial Supervision’ of the 2017 CPL; therefore, the finality of such a judgment may be challenged (if it does reopen the retrial). Following Article 16 of the Regulations, judgment, rulings (caiding) and mediation agreement (tiaojieshu) are all subject to such a retrial procedure.Footnote 118 Article 200 of Chapter 16 of 2012 and 2017 CPL provides 13 circumstances under which a retrial procedure must be initiated for a technically final judgment.Footnote 119

In China, the retrial procedure is very controversial. The circumstances under which a ‘final’ judgment can be subject to retrial have been revised frequently. Article 157 of the 1982 CPL (trial version) provided that mistake(s) in the judgment was the basis for initiating a retrial procedure; the 1991 CPL listed five circumstances (Article 177); in its 2007 revised version, there were 13 circumstances including ‘where jurisdiction is erroneously exercised in violation of the provisions of law’ (Item 7 of Article 179); in its 2012 and 2017 revised version this circumstance was replaced by the following circumstance: ‘when adjudicating the case, a judge commits embezzlement, accepts bribes, practices favoritism for personal gains, or adjudicates by distorting the law’. The 2015 Judicial Interpretation of the CPL included additional stipulations in Chapter 18 regarding the application of such retrial circumstances as provided by the 2017 CPL.

The concerns regarding the retrial of a technically ‘final’ decision are not unique for the CICC as all judgments in China are subject to such a retrial procedure. However, the possible problem arising from this regime may be more evident for the CICC, as it is more likely that its judgments will need recognition and enforcement in a foreign jurisdiction. However, this problem relates to broader issues regarding the retrial procedure in China and should be the subject of further research.

V. ADDRESSING STATUTORY IMPEDIMENTS TO INNOVATION FOR THE CICC

When compared with arbitration, the CICC has both advantages and disadvantages. In terms of disadvantages, unlike in arbitration where the parties are able to appoint the arbitrators, it is not possible to determine the judges who hear cases before the CICC. Whilst arbitral awards or judgments can be recognised and enforced in the 160 States parties to the New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards (1958), the recognition and enforcement of court judgments, including those of the CICC, still face obstacles.

However, the CICC offers some advantages, such as its mediation function and information system as well as favourable procedural rules (such as simplified evidential rules) and enforcement of its judgments within the territory of China (arbitration awards, on the other hand, need to be reviewed and enforced by courts). Another important factor is the cost of litigating before the CICC (or fees for those cases transferred to mediation by the CICE or other institutions). Although the costs of doing so are still not clear from publicly available information, it may well be more cost-effective than arbitration and so offer a competitive alternative to arbitration.

To improve its competitiveness, however, the CICC should address various statutory impediments in a way that is similar to other international commercial courts. For example, Article 9 of the Chinese Judges Law (last revised in 2017) stipulates that a judge in China must have the nationality of the People's Republic of China. This prevents the CICC appointing international judges and significantly reduces the number of capable candidates with good international profiles. A further barrier is Article 162 of 2017 CPL which stipulates that when a people's court hears a foreign-related civil (or commercial) case, it should use the language and characters commonly used in the People's Republic of China. It is obvious that finding international judges able to use Chinese as the working language, or Chinese judges able to use English at a professional level presents additional hurdles. To date, the scope of practice of foreign lawyers in China has been limitedFootnote 120 and foreign lawyers are not allowed to present argument in cases heard by a people's court. Article 263 of the 2017 CPL provides that if a foreigner, stateless person, foreign enterprise or organisation sues or responds to a lawsuit in a people's court and needs legal representation, this must be provided by a lawyer of the People's Republic of China. It would be desirable to change this in order to promote the development of the CICC. For example, the CICC could assign international judges or domestic judges (or a combination of both) to a case, and let them decide the working language (English or Chinese) according to the nature of the case and could also invite foreign lawyers to appear in matters governed by foreign law.

Such impediments are not unsurmountable. In the past few years, China has launched various judicial reforms that go beyond the existing statutory framework with the approval of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress (SCNPC), the permanent representative body of the National People's Congress (NPC).Footnote 121 The same approach could be taken in relation to the CICC. As explained previously, in addition to the SPC, China's courts can be divided into local people's courts and special people's courts. Article 15 of Organisation Law of the People's Courts in the People's Republic of China (2018) provides that the organisation and powers of special people's courts must be separately prescribed by the SCNPC. Although the CICC, as part of the SPC, is not strictly speaking a special court, it arguably has a special nature. Thus, China could consider converting the CICC into a separate special court and empower the SCNPC to provide for the organisation and powers of the CICC, as happened in the case of the Shanghai Financial Court.Footnote 122 For example, it could allow foreign lawyers to present cases before the CICC. It could also allow the CICC to appoint foreign judges and adopt a more flexible approach to its procedures. As such innovations would be limited to the CICC (as a special court), there would not be significant implications for China's judicial system as a whole.

VI. CONCLUSION

The CICC should be of benefit to China in promoting its participation in global business law-making, and better integrating China into global arrangements for judicial cooperation and recognition. This is in accordance with China's desire to play a more positive and influential role in rule making for international business and other affairs.Footnote 123 Although China has some influential arbitration centres, such as the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission, their ability to promote the development of substantive commercial law appears to be limited because of their ad hoc nature and the confidential nature of arbitration awards.Footnote 124 As stated by Chief Justice Marilyn Warren and Justice Clyde Croft of the Supreme Court of Victoria in Australia, ‘[s]uch (international commercial) courts can be instrumental in facilitating the harmonisation of commercial laws and practices. They also represent an avenue for the advancement of the rule of law as a normative ideal in global commerce. This is because there will be greater external scrutiny of their decisions and processes, with increased pressure to justify decisions against international norms.’Footnote 125 The CICC could be beneficial for such purposes.

So far, the CICC has established a basic framework for its operation and has made a good start for its future development. However, a basic question remains as to whether its innovations are bold enough to realise its full potential, given that most of the measures it has adopted still follow the practices of existing Chinese courts. Looking forward, it should instead prioritise internationalisation, professionalism and transparency. Only in this way can the CICC become a genuine competitor in the fierce global competition for international commercial dispute settlement. If the CICC can absorb international standards and practices, it will provide significant insights into the potential for more general law reform in China, enhance global recognition and enforcement of its judgments, improve the credibility of the judicial system and, more generally, help in the development of the rule of law in China.