Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) are an important cause of healthcare-associated infection (HCAI) and are associated with increased mortality, lengthened hospital stays and significant economic burden.Reference Humphreys 1 , Reference Jung, Byun, Lee, Moon and Lee 2 In 2013, cases of VRE in hospitalized patients in the United States numbered 20,000 and were associated with 1,300 deaths. Of these cases, 77% were Enterococcus faecium (VREfm) and the remainder were Enterococcus faecalis (VREfl). 3 In Europe, invasive E. faecium isolates reported to the European antimicrobial resistance surveillance network EARS-net in 2015 numbered 9,123, with glycopeptide resistance ranging from 0 to 45.8%. 4 Of 29 reporting countries, Ireland had the highest rate of VRE at 45.8%.

VRE colonization and environmental contamination are associated with transmission to other patients,Reference Papadimitriou-Olivgeris, Drougka and Fligou 5 , Reference Boyce 6 and infection prevention and control (IPC) measures, including active surveillance cultures (ASC), isolation of VRE-positive patients and contact precautions are recognized as important.Reference Humphreys 1 In Ireland, ASC for VRE is recommended for intensive care unit (ICU) admissions. The reasons for the high VRE rate in Ireland are unknown and may be better informed by epidemiological investigations of VREfm in an Irish setting, which has been limited to date.Reference Ryan, O’Mahony and Wrenn 7 The aims of this study were (1) to identify potential reservoirs of VREfm in an ICU, (2) to investigate the clinical and molecular epidemiology of VREfm outside of outbreaks in the ICU, and (3) to assess the role of VRE ASC in this setting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting

Beaumont Hospital, Dublin, is an 820-bed tertiary referral teaching hospital. It is the national referral center for neurosurgery, cochlear implantation, neurology, and renal transplantation and is a regional referral center for many specialties for northeastern Ireland. The study took place in the 12-bed general ICU with 6 bed spaces in an open-plan area, 4 single rooms, and 2 air-controlled isolation rooms (rooms 11 and 12, Figure 1). The 2 isolation rooms are occupied less frequently (eg, due to requirements for additional nursing staff) unless they are clinically required for logistical reasons. According to national guidelines, patients are screened for VRE on ICU admission and weekly thereafter and are isolated with contact precautions if they are VRE-positive. Previously known VRE-positive patients are isolated on admission. Cleaning of the ICU environment is performed by a dedicated member of the cleaning staff who is rostered from 07:00 to 19:00 hours, and an on-call service is available outside these times. Bed spaces are cleaned 1 at a time using 1,000 ppm sodium dichloroisocyanurate (Precept, Advanced Sterilization products, Ontario, Canada). Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Beaumont Hospital Ethics Committee.

FIGURE 1 Detection of vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) in the intensive care unit (ICU). The ICU layout indicating beds in the 6-bed open-plan area and isolation rooms (a) and the total number of sites and patients positive for VRE in isolation rooms 7–10 compared to the open-plan area (ie, beds 1–6) during 7 sampling periods (b). The negative-pressure isolation rooms (11 and 12) were excluded from the comparison due to their low-frequency use (2 patients over the study period). *** indicates statistical significance, P < .0001.

Environmental Sampling

Environmental sampling took place during 7 sampling periods within a 32-month time frame: October 2012 through June 2014. During each sampling period, the environment of occupied ICU bed spaces was sampled twice weekly between 10:00 and 12:30 hours for 3 consecutive weeks. A patient bed space was defined as the near-patient environment in isolation rooms or open-plan area in which 6 ‘high-touch’ sites were sampled. Each area was swabbed using Copan eSwabs (Copan Diagnostics, Italy). A ~5-cm2 area was swabbed on flat surfaces. A sampling occasion refers to the sampling of multiple surfaces of an occupied patient bed space on a single day. Because only occupied bed spaces were sampled, the number of sampling occasions in each time period varied with ICU occupancy levels.

Identification of VRE From Patient Swabs

Rectal swabs, taken from patients on admission to the general ICU as part of an ASC program, were processed for identification of VRE by the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory, Beaumont Hospital. Swabs were plated onto selective ChromeID VRE and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. Organism identity was confirmed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) using a MALDI Biotyper (Brüker). The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for vancomycin was determined using E-test strips (Biomerieux). Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 and E. faecalis ATCC 51299 were negative and positive control strains.

Recovery of VRE From Environmental Samples

Swabs were transferred to brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (2 mL) for enrichment and were incubated overnight (16–18 hours) at 37°C in a shaking incubator (Gallenkamp, Leicester, UK) at 150–200 rpm. A 10-µL loop of enriched suspension was streaked onto UTI Brilliance agar (Oxoid, UK), and turquoise colonies (presumptive enterococci) were subcultured onto VRE ChromeID and confirmed using MALDI-TOF MS. Vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined using E-tests. Patient clinical details were collected at the time of sampling.

Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) for VRE

Sma1-digested genomic DNA from patient and environmental VREfm and E. faecalis ATCC 29212 were subjected to PFGE based as described by Turabelidze et alReference Turabelidze, Kotetishvili, Kreger, Morris and Sulakvelidze 8 but with modifications, including standardization to a size referenceReference Ribot, Fair and Gautom 9 (as outlined in supplemental file S1).

Statistical Analyses

Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze categorical variables using GraphPad QuickCalcs online software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). The significance of differences between the groups was expressed as 2-tailed P values; P≤.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of VRE Patients in the ICU

Of 157 patients sampled, 30 patients (19%) were VRE colonized. Clinically relevant patient details for VRE-colonized patients are summarized in Table 1. Among the colonized patients, 18 patients (60%) were admitted from another ward in the hospital. Not all VRE-positive patients had contemporaneous viable isolates of VRE. Of the VRE-positive patients included, 2 were treated for invasive VRE infection: 1 was treated for a catheter-related bloodstream infection (BSI) and the other was treated for VRE surgical-site infection. Both patients had initially been treated with vancomycin.

TABLE 1 Demographics and Clinical Details of Patients Colonized With the VRE in the ICU

NOTE. VRE, vancomycin-resistant enterococci; VREfm, Enterococcus faecium; VREfl, Enterococcus faecalis; APACHEII, Acute Physiological and Chronic Health Evaluation Score; ICU, intensive care unit.

a Unless otherwise specified.

b Antibiotics received included piperacillin/tazobactam, co-amoxiclav, vancomycin, clarithromycin.

Potential Reservoirs of VRE in the ICU

Of 1,647 swabs taken from the environment of 157 patients in the ICU, 107 sites (6.5%) were positive for VRE. These isolates were recovered from the 6-bed open-plan area (n=35), 4 single rooms (n=67), and 2 negative-pressure isolation rooms (n=5). Significantly more VRE isolates were recovered from the environments of single rooms, where the majority of VRE-positive patients were located (ie, beds 7–10) than from the open-plan area (ie, beds 1–6; P < .0001) (Figure 1). Based on the number of environmental swabs taken, rates of contamination with VRE were 4.1% in open-plan rooms and 9.1% in isolation rooms. During the study, beds 11 and 12 were used infrequently to isolate VRE patients (2 patients). Of 157 patients, 69 patients (44%) occupied beds 7–10 at least once over the study duration, and 24 of these 69 patients (34.8%) were colonized with VRE. In total, 26 of 30 VRE-positive patients (86%) were isolated at the time of sampling.

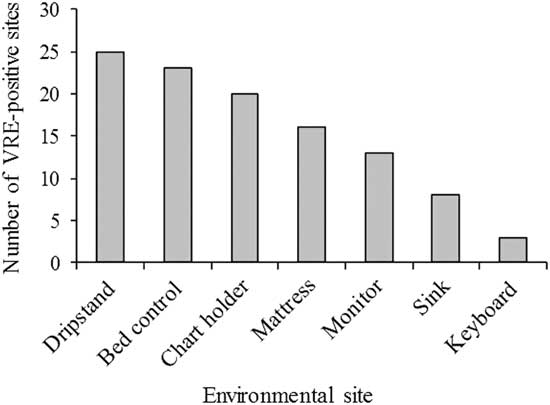

The specific high-touch ICU sites most frequently contaminated with VRE were the drip stand, bed control panel, and chart holders. Together, these areas accounted for 61% of contaminated sites (Figure 2). The difference in the proportional recovery of VRE from any 1 surface was not statistically significant.

FIGURE 2 Distribution of vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) on high-touch surfaces adjacent to patients in the ICU. Total surfaces sampled, 1,647; total VRE-positive surfaces, 107. Chart holders were replaced with keyboards during the study. Control buttons were sampled on patient monitors.

The Positive Impact of ASC on VRE Recovery From ICU Patients

The use of ASC resulted in the identification of an additional 19 of 157 VRE-colonized patients (11.6 %) compared to 11 of 157 (7%) identified from nonscreening or clinical samples (eg, urine samples) in the absence of ASCs. This finding represents a 172% increase in VRE detection rates with ASCs. In the 19 new cases, 14 patients were VRE positive on ICU admission (ie, within 48 hours), and 5 patients acquired VRE in the ICU. These patients were isolated once VRE was recovered from screening swabs, according to local IPC guidelines.

Clinical Epidemiological Associations Between Patient and Environmental VRE

Over the 7 sampling periods, a total of 289 ICU sampling occasions (defined as the sampling of multiple touch sites in a single bed space on a single day) involved 157 ICU patients. On 114 of 289 sampling occasions (39.4%), VRE was recovered from the patient bed space, the patient clinical sample, or both. For 34 of 114 (29.8 %), both the patient and their bed space were positive at the time of sampling. For the remainder of sampling occasions in which VRE was recovered, either the patient (44 of 114, 38.6%) or their environment (36 of 114, 31.6%) was positive for VRE.

To investigate potential transmission events related to the movement of patients within the ICU, 189 unique patient and bed-number associations involving 157 patients were identified (ie, some patients occupied >1 ICU bed within the study period). Tracking the pattern of recovery of VRE with respect to time and bed space revealed 6 possible VRE transmission events. Of these, 4 were from patient to environment (recovery of VRE from an environmental site (bed spaces 7, 8, and 9), which was previously negative but became positive within 2–4 days of a VRE-positive patient occupying the bed space). A further 2 possible transmissions of VRE from environment to patient were identified. In 1 case, the patient became VRE positive 9 days after admission and placement in an environment that sampled positive for VRE. The other involved a patient acquiring VRE having spent 48 hours in a room where the environment was VRE positive.

Molecular Epidemiology of VREfm From the ICU

In total, 137 VRE isolates were recovered during this study, including E. faecium, E. faecalis, E. gallinarum, and an isolate of Paenibacillus spp. Of these, 71 VREfm isolates were typed using PFGE, which included 49 environmental and 22 patient isolates from 17 patients (some patients had >1 isolate). Our analysis revealed 32 distinct PFGE types and 3 PFGE clusters. Clusters A, B, and C and their association with bed spaces and patients are summarized in Figure 3. Clusters A (n=8 isolates) and B (n=9 isolates) were exclusively environmental isolates from multiple bed spaces during separate sampling periods (periods 1 and 5). Cluster A isolates were recovered within a 2-day period (sampling period 1) from 5 bed spaces, including isolation rooms and the open-plan area (beds 2, 6, 7, 8, and 9). Cluster B included 9 isolates; 8 were recovered on a single day (sampling period 5) from 3 bed spaces (beds 4, 8, and 9). The ninth isolate was recovered 2 days later from bed 8. Cluster C contained 5 isolates: 4 patient isolates from 3 patients and a fifth environmental isolate. These 3 patients had occupied 2 separate bed spaces at different times. The environmental isolate was unrelated in space and time to the patient isolates. This patient was readmitted to the ICU, having been previously VRE colonized, and the patient developed a VRE BSI 20 days later. The 2 other patient isolates in this cluster were from patients who were in the ICU at the same time as the first patient (sampling period 2), and 1 of these patients developed a VRE BSI 1 month later (this patient’s rectal swab contained vancomycin-susceptible E. faecium). Another 2 patients, in bed spaces 9 and 11, in different sampling periods had genetically indistinguishable VRE. A detailed dendrogram of VREfm isolates is provided in supplemental file S2.

FIGURE 3 Clusters identified by PFGE analysis and patient bed-space associations. From 71 VREfm isolates investigated, 3 clusters (A, B, and C) were identified. Clusters A and B (light grey and dark grey bars) were exclusively environmental isolates recovered in sampling periods 1 and 5). Cluster C (patterned bars) contained 4 patient isolates (P) and 1 environmental isolate (E).

DISCUSSION

The microbiome of the ICU is variable and factors include the patient cohort, changes in staff, cleaning regimens, IPC policies and compliance, and impact on microbial population dynamics. Here, the overall contamination of the ICU environment with VRE was 6.5% of environmental sites sampled. A similar rate of 6.0% contamination based on 6 high-touch surfaces in 37 ICU rooms was previously reported.Reference Goodman, Platt, Bass, Onderdonk, Yokoe and Huang 10 Notably, we did not limit our study to the bed spaces of patients with VRE, an approach taken by others, which may yield greater numbers over longer sampling periods. For example, 21% of environmental VRE contamination was reported in the rooms of VRE-colonized patients at baseline in a US intervention study in a similar setting with similar sampling methodologies.Reference Hota, Blom, Lyle, Weinstein and Hayden 11 However, an intervention study comparing multiple surfaces from rooms housing VRE-colonized and noncolonized patients reported 23.6% and 5% contamination, respectively.Reference Hayden, Bonten, Blom, Lyle, van de Vijver and Weinstein 12 These rates were higher than the rates found in this study (9% and 4.1%, respectively).

Our study confirms previous reports that surfaces close to patients and frequently touched by staff harbor the majority of VRE.Reference Dancer 13 Most VRE-positive samples were recovered from isolation rooms 7–10, where VRE-colonized patients were accommodated once they were identified as VRE positive, and this finding is supported by the literature. Prior room contamination increases the risk of patient acquisition of VRE. Reference Drees, Snydman and Schmid 14 Isolation rooms 7–10 were significantly more contaminated than the open-plan area. Standard size recommendations exist for ICU isolation rooms. 15 The cramped conditions in smaller-sized rooms (eg, beds 7–10 in this study) may hamper proper cleaning of the environment, which may contribute to VRE persistence.

Patients in our ICU are screened on admission and weekly thereafter for VRE and a colonization rate of 30 of 157 (19.1%) was detected over the study period. A recent meta-analysis reported an average VRE colonization rate of 8.8% across 37 studies including 62,959 patients at risk. Furthermore, VRE colonization on ICU admission was higher in US studies (12.3%) than in studies from Europe (2.7%) and elsewhere.Reference Ziakas, Thapa, Rice and Mylonakis 16 While Ireland has the highest VRE BSI rate in Europe, data on ICU colonization rates are not widely available. In this study, the positive effects of ASC on VRE detection were evident. A new finding of VRE colonization was confirmed in 19 of 30 patients who were subsequently isolated within the unit, representing a 172% increase in detection rate with this approach. A recent Canadian longitudinal multicenter study indicated no significant impact on clinical outcomes following the removal of all VRE controls, including screening.Reference Lemieux, Gardam and Evans 17 While other challenges, such as MRSA, have received significant attention, the significant complications of VRE colonization and infection in vulnerable ICU patients,Reference Whelton, Lynch and O’Reilly 18 in addition to the high rate of VRE invasive infection reported in Ireland, warrant the implementation of effective IPC strategies.

Molecular typing by PFGE revealed genetic diversity among patient isolates, whereas the environmental isolates showed more clonal relationships. The acquisition of resistant determinants by susceptible enterococci in the gut, under antibiotic pressure,Reference van Schaik, Top and Riley 19 may contribute to the heterogeneity observed here among patient isolates. Acquisition of vanB associated with the transposon Tn1549 by susceptible enterococci from anaerobes of the gut flora has been shown previously.Reference Howden, Holt and Lam 20 , Reference Ballard, Pertile, Lim, Johnson and Grayson 21 The more clonal pattern of environmental isolates found here suggests that the environment may select for certain clones.

Our study identified potential transmission of VRE within the unit based on the movement of patients between bed spaces. Furthermore, molecular epidemiological analysis identified 2 patients who were in the unit at the same time, in single rooms at either end of the unit, with closely related VRE suggesting transmission facilitated by poor hand hygiene and/or environmental hygiene. The heterogenic nature of colonizing isolates reported in this and other studies suggests horizontal rather than clonal transmission. While this pattern of transmission highlights the importance of implementing effective IPC measures, in a nonoutbreak setting, evaluation of which methods (eg, patient isolation and/or environmental cleaning) are most effective in reducing transmission to patients require well-designed intervention studies supported by detail epidemiological investigations.

This study had limitations. Because VRE transmission dynamics were monitored discontinuously for logistical and cost reasons, some transmission events were not captured. Hand carriage of VRE by healthcare workers was not investigated and may contribute to VRE transmission. Genetic relatedness of a subset of study isolates (66%) was conducted by PFGE. While this was discriminatory in identifying clusters or confirming heterogeneity, there is no standard protocol for VRE PFGE or for data interpretation. More discriminatory but expensive approaches (eg, multilocus sequence typing, whole-genome sequencing) might have provided more robust characterization of isolates. However, we demonstrated that the application of molecular typing (PFGE) could potentially, in real time, provide indications of VRE transmission that could assist improved IPC measures in a setting where the physical infrastructure (ie, limited space and too few isolation rooms) is inadequate.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Ms Mary O’Connor and Ms Margaret Fitzpatrick of the Department of Microbiology, Beaumont Hospital, and the ICU Beaumont staff and patients for facilitating this study.

Financial support: No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Potential conflicts of interest: H.H. has received research support from Pfizer and Astellas in recent years. All other authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2017.248