Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) are multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria that colonize and infect many patients yearly. A subset of CRE, carbapenemase-producing CRE (CP-CRE), are worrisome because they may be responsible for increasing CRE spread in the United States. 1–Reference Fitzpatrick, Suda and Ramanathan3 The Department of Veterans’ Affairs (VA) distributed guidelines in 2015 and updated them in 2017, with a focus on CP-CRE. The guidelines provide information on (1) laboratory identification of CRE including PCR testing for carbapenemases; (2) CRE surveillance, including recommendations for active screening; and (3) infection prevention practices, such as contact precautions and communication within and across healthcare facilities. Findings related to VA guideline laboratory practices showed that most VA laboratories use VA guidelines, but variation existed in CP-CRE identification. Reference Bart, Paul, Eluk, Geffen, Rabino and Hussein4 We now report on an analogous survey identifying practices related to infection prevention and control of CRE and/or CP-CRE in VA facilities.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted via an electronic survey of 161 multidrug-resistant organism (MDRO) prevention coordinators (MPCs) at 134 VA Medical Centers (VAMCs) between February 21 and April 30, 2018. MPCs assist with data collection and reporting for MDRO surveillance at most facilities. The survey focused on experiences and practices related to CRE and/or CP-CRE (represented as “CRE/CP-CRE”). It was developed in collaboration with the VA MDRO Program Office and was administered through Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap). The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) was used to develop and analyze implementation questions. Reference Damschroder, Aron, Keith, Kirsh, Alexander and Lowery5

Other characteristics collected regarding VA facilities included rural versus urban location and facility complexity from the VA Office of Productivity, Efficiency, & Staffing (OPES) Facility Complexity Model. 6 The OPES classifies complexity based on patient characteristics, complex clinical research, and teaching programs (levels 1a–c, 2, and 3). For this analysis, levels 1a–c were considered high complexity and levels 2 and 3 were considered low complexity. 6

All survey responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Comparisons of facility complexity, rurality, reported CRE/CP-CRE experience, and nonresponse were assessed using the Fisher exact test. Facility history of CRE/CP-CRE experience was defined as facilities reporting any CRE/CP-CRE. If no cases of CRE/CP-CRE were reported, facilities were defined as not having CRE/CP-CRE experience. Questions were categorized ‘agree’ if respondents ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ with the statement and ‘did not agree’ if they responded ‘neutral,’ ‘disagree,’ or ‘strongly disagree.’ All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

In total, 81 MPCs (50.3% of 161 MPCs) from 79 unique facilities (58.9% of 134) responded, including 2 facilities with unique MPCs for acute-care and long-term care unit(s) (n = 4). Responding facilities did not differ significantly (P > .05) from nonresponding facilities by facility complexity (high complexity, 69.1% vs 63.8%), geographic location (urban, 79.0% vs 83.8%), or presence of a long-term care center (85.2% vs 92.5%) or spinal cord injury center (21% vs 17.5%). In addition, 70.4% of respondents reported some CRE/CP-CRE experience.

Most MPCs reported using VA guidelines (97.5%, either 2017 or 2015). Also, 17 MPCs (20.9%) reported routinely screening for CRE/CP-CRE colonization (Figure 1 shows the types of patients screened). The most common reason for not screening was not having a CRE/CP-CRE problem (70.4%). Beyond implementing contact precautions, other infection control processes for CRE/CP-CRE–positive patients included patient (24.7%) and/or nurse cohorting (7.4%).

Fig. 1. Proportion of types of patients routinely screened (among those that do screening/active surveillance, n = 17). *Other includes the following: patients with multiple admissions to acute care, transfers from outside the intensive care unit (ICU), community living center (CLC) transfers, or when the physician suspects it.

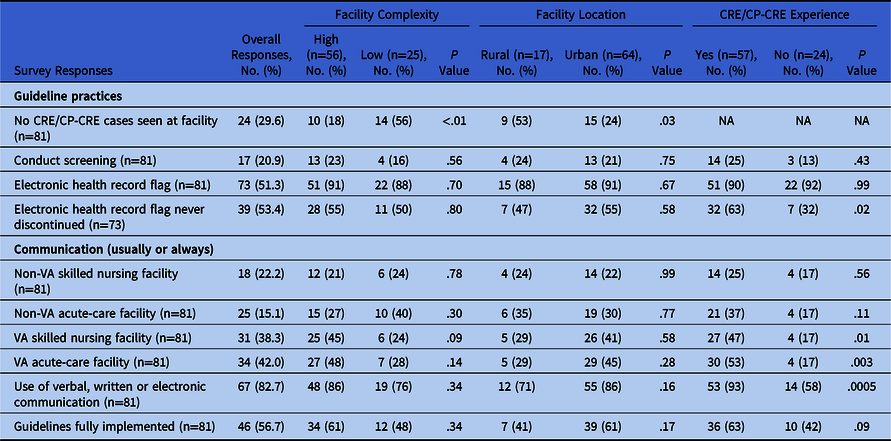

Nearly all MPCs (90.1%) used an electronic health record (EHR) flag available to notify providers about patients with CRE/CP-CRE, with half indicating the flag is ‘never’ discontinued (Table 1). Other flag removal responses included ‘after 1 year’ (15.1%) and ‘other’ criteria including but not limited to ‘2 negative rectal swabs’ or ‘on a case-by-case basis.’

Table 1. Survey Responses by Facility Complexity, Location, and CRE Experience

Note. VA, Veterans’ Affairs.

Table 1 illustrates differences in responses by facility complexity level, location, and CRE/CP-CRE experience. Lower complexity and rural facilities were more likely to report no CRE/CP-CRE at their VAMC in the last year. Respondents from high complexity and urban sites were significantly more likely to report actively screening patients at admission. Respondents from facilities with CRE/CP-CRE experience were more likely to never discontinue the EHR flag.

Respondents indicated that they typically received little to no information on patients’ CRE/CP-CRE status when transferred between facilities (Table 1). MPCs reported more often receiving communication on CRE status when their patient was transferred from a VA skilled nursing facility or an acute-care hospital versus a non-VA skilled nursing facility or an acute-care hospital. Similarly, in acute care, information on patient CRE status was received most frequently from VA facilities versus non-VA facilities. Respondents from facilities with CRE/CP-CRE experience more frequently reported ‘usually’ or ‘always’ obtaining CRE/CP-CRE status when transferring from a VA facility. Patients’ CRE/CP-CRE status was most frequently communicated verbally or via interfacility transfer forms (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Mode of communication when transferring CRE/CP-CRE patients from their facility to another facility (n = 81).

Most respondents (85.0%) ‘agreed/strongly agreed’ that they are knowledgeable about the CRE/CP-CRE guidelines. However, only half ‘agreed’ that they had the physical (56.8%), staffing (55.6%), and laboratory resources (65.1%) to accomplish guideline activities. More facilities experiencing CRE/CP-CRE described having adequate physical resources necessary to accomplish guidelines activities (75.0% vs 49.0%; P = .05). Also, 56.8% reported the CRE/CP-CRE guidelines are ‘fully’ implemented at their facility. The main reason reported for guidelines not being fully implemented was lack of active surveillance (59.3%).

Discussion

In the survey results, 29.6% of VA acute-care facilities reported no experience with CRE/CP-CRE, and only a small percentage reported performing active surveillance for CRE/CP-CRE. As of 2017, CRE/CP-CRE has been reported in every state 2 ; therefore, it is critical that all VA facilities are prepared. Implementing CRE/CP-CRE screening is not straightforward; it requires a multidisciplinary plan that allocates resources and time to establish a new process. At sites that are screening, we found variability in the types of patients screened, and respondents reported lack of resources.

An interesting survey finding relates to CRE/CP-CRE EHR alerts. Reference Martischang, Buetti, Balmelli, Saam, Widmer and Harbarth7 Currently, no guidelines or conclusive evidence supports discontinuing alerts and contact isolation for patients with CRE/CP-CRE. Reference Bart, Paul, Eluk, Geffen, Rabino and Hussein4 Hospitals determine their own protocols, based on expert opinion, local MDRO epidemiology, and previous experience with other MDROs. Although most VAMCs reported that they never discontinue the alert, respondents also described other methods that could assist other facilities in establishing protocols for CRE/CP-CRE alerts and contact isolation.

Communication is a key strategy to improve infection control and to interrupt the spread of CRE. Reference Lee, Bartsch and Wong8 Unfortunately, our survey revealed that positive CRE/CP-CRE status is communicated less than half the time to the patient, a finding previously demonstrated in other studies including those in non-VA settings. Reference Trepanier, Mallard and Muenier9,Reference Shimasaki, Segreti, Tomich, Kim, Hayden and Ling10 The greater proportion of respondents reported transfer communication between VA facilities in our survey is encouraging and may be due to their common EHR. However, the implementation of standardized interfacility transfer notification and the development of regional CRE/CP-CRE registries are important steps toward improving communication. To this end, the VA is actively working on implementing a systemwide automated CP-CRE notification system.

Our study was limited by being conducted in the VA, where responses and practices may differ compared with non-VA hospitals. Furthermore, selection bias is possible with only 59% of VAMCs responding; however, we detected no differences in key characteristics between responding and nonresponding facilities. Finally, recall bias may have affected the accuracy of responses, given that this was a cross-sectional survey of self-reported practices related to CRE.

In conclusion, almost all MPCs reported using the VA CRE/CP-CRE guidelines. However, gaps in implementation include the lack of CRE/CPE CRE screening and communication about CRE/CP-CRE status during transfer. Additional work is needed to overcome barriers to guideline implementation and provide stronger education and resources to help support guideline activities for the prevention of MDROs.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2020.328

Acknowledgments

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans’ Affairs or the US government.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Veterans’ Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (grant no. QUE 15-269).

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures relevant to this article.