Understanding routes of pathogen transmission in healthcare settings is essential for development of effective control measures. In recent years, molecular typing techniques, such as whole-genome sequencing, have provided highly discriminatory methods to determine the relatedness of pathogens recovered from patients and the environment. To identify potential routes of transmission, these methods are typically used in conjunction with tracking of patient movement.Reference Kong, Eyre and Corbeil 1 , Reference Donskey, Sunkesula and Stone 2 One striking observation from many studies using discriminatory typing methods is that genetically related organisms are often detected in patients with no shared exposure on the same ward.Reference Kong, Eyre and Corbeil 1 – Reference Curry, Muto and Schlackman 4 For example, Kong et al1 reported that 23% of incident hospital-associated Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) cases shared genetically related strains with prior hospitalized CDI cases or asymptomatic carriers who were never on the same ward. Such linkages have either not been considered plausible transmission events or have been classified as potential non-ward transmissions.Reference Kong, Eyre and Corbeil 1 – Reference Curry, Muto and Schlackman 4

Benign surrogate markers, such as nonpathogenic viruses and viral DNA, provide powerful tools to investigate pathogen transmission.Reference Alhmidi, John and Mana 5 – Reference John, Alhmidi, Cadnum, Jencson and Donskey 7 On individual wards, surrogate markers inoculated onto surfaces were disseminated to environmental sites and patients.Reference Koganti, Alhmidi, Tomas, Cadnum, Jencson and Donskey 6 , Reference John, Alhmidi, Cadnum, Jencson and Donskey 7 Because personnel and equipment often move between wards, we hypothesized that ward-to-ward dissemination of pathogens might be common in the absence of shared ward exposure. Here, we used a DNA surrogate marker that is not affected by alcohol hand sanitizer in conjunction with observations of personnel to investigate the potential for dissemination from contaminated equipment on one hospital ward to other sites in the hospital.

Methods

Setting

The Cleveland Veterans Affairs Medical Center is a 215-bed acute-care hospital with 6 medical-surgical wards and 2 intensive care units. Portable equipment includes devices that are typically dedicated to a ward (eg, bladder scanners) and devices that are routinely shared (eg, wheelchairs). Nursing staff are primarily based on a single ward, whereas physicians care for patients on multiple wards. The study protocol was approved by the facility’s institutional review board.

Characteristics of the viral DNA surrogate marker

The surrogate marker for pathogen transmission was a 222-base pair DNA marker from the cauliflower mosaic virus.Reference Alhmidi, John and Mana 5 , Reference John, Alhmidi, Cadnum, Jencson and Donskey 7 In simulations of patient care, 1 μg DNA surrogate marker was transferred from a contaminated mannequin to environmental surfaces in a manner similar to bacteriophage MS2 and nontoxigenic C. difficile spores, both with a relatively large inoculum size of 105 plaque-forming or colony-forming units, respectively.Reference Alhmidi, John and Mana 5 The DNA marker remained detectable for weeks on surfaces by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and was inactivated by bleach. The DNA marker was not inactivated by quaternary ammonium disinfectants or alcohol but was reduced to undetectable levels through mechanical removal by hand washing and by wiping of surfaces with antimicrobial or nonantimicrobial wipes.Reference Alhmidi, John and Mana 5

Dissemination of the DNA surrogate marker

We inoculated 1 μg of DNA marker in 30 μL water onto high-touch areas of 6 portable devices on a medical ward, including 3 bladder scanners, an electrocardiogram machine, a portable vital signs device, and a cardiac monitor. Hospital personnel and patients were not aware of the study. A fluorescent marker was placed on the equipment adjacent to the marker to allow an assessment of cleaning.

For a 3-day period after inoculation, research personnel conducted observations to identify episodes when the contaminated equipment was shared by other wards or used by personnel who subsequently moved to other areas of the hospital. If such episodes were observed, cotton-tipped swabs were used to sample 5 × 10-cm areas of surfaces, prioritizing sites observed to be contacted by personnel or equipment. Additional swabs were collected from physician call rooms and nursing stations on other wards.

To further assess the potential for ward-to-ward transmission by contaminated equipment, we inoculated mobile wound-care carts on 3 separate days and a phlebotomy cart on 1 day. Personnel using these items were observed and swabs were collected to identify sites of marker transfer.

Results

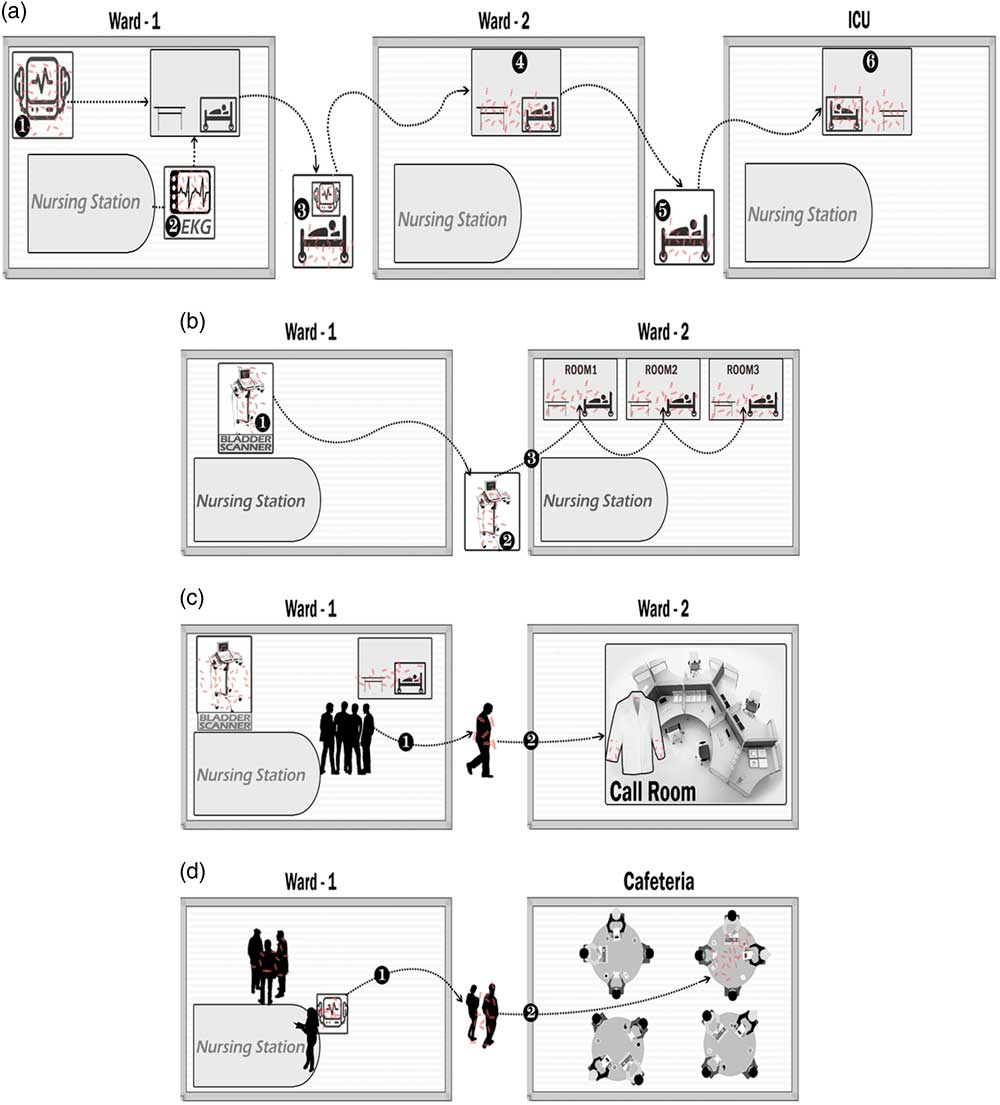

During the 3-day study, each inoculated device was observed being used at least once, but the fluorescent marker was removed from only 1 of 6 devices (17%). Two inoculated devices were used on other wards, including a cardiac monitor that moved with a transferred patient and a borrowed bladder scanner. Transfer of the DNA marker to surfaces on the other wards occurred with both episodes of equipment sharing (Fig. 1A and 1B). The DNA marker was recovered from the sleeves of a physician’s white coat hung in a call room on another ward (Fig. 1C) but not from other call rooms or from nursing stations. The marker was recovered from a table top in the cafeteria where personnel sat after use of the inoculated equipment (Fig. 1D). Overall, 7 of 96 swabs (7%) were positive.

Fig. 1 Transfer of a viral DNA surrogate marker from inoculated portable equipment on a medical ward to environmental surfaces on other wards or other sites in the hospital during a 3-day period. The DNA marker was inoculated onto 6 items of portable equipment on the index ward including 3 bladder scanners, an electrocardiogram machine, a portable vital signs unit, and a cardiac monitor. Observations were conducted to identify episodes when the contaminated equipment was shared by other wards or used on the index ward by personnel who subsequently moved to other areas of the hospital. Swabs were used to sample environmental surfaces, prioritizing sites observed to be contacted by personnel or equipment. (A) A contaminated cardiac monitor (1) and electrocardiogram (EKG) machine (2) were used while caring for a patient who was then transferred with the cardiac monitor attached (3) to ward 2 (4) and then without the monitor to the intensive care unit (ICU) (5 and 6), resulting in detection of DNA marker on surfaces on each ward. (B) A bladder scanner (1) was borrowed by a nurse from another ward (2) resulting in transfer to 3 patient rooms where it was used (3). (C) A physician used contaminated equipment on ward 1 (1) and DNA marker was subsequently recovered from the sleeves of the physician’s white coat that was hung in a physicians’ work room on ward 2 (2). (D) Personnel on the index ward used contaminated equipment (1) and then went to the cafeteria for break, resulting in recovery of DNA marker from a table top (2).

During observations of wound-care rounds, the DNA marker was transferred from the inoculated cart to surfaces on 2 of 3 observation days. On 3 different wards, the marker was detected on surfaces touched by hands or gloves of personnel after contact with the wound-care cart, including a door knob, a bedrail, and a workstation on wheels. During observation of a phlebotomist, DNA marker was transferred to surfaces in 3 of 9 patient rooms (33%) on 2 wards.

Discussion

In investigations of pathogen transmission, shared ward exposure is often required for classification as a plausible epidemiologic link. However, sharing of personnel and equipment is common, and patients from multiple wards regularly intersect in areas such as radiology.Reference Jencson, Cadnum, Wilson and Donskey 8 , Reference Murray, Yim and Croci 9 In a previous report, hospital-wide dissemination of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus was linked to a colonized healthcare worker caring for patients on multiple wards.Reference Boyce, Opal, Potter-Bynoe and Medeiros 10 In the current study, we used a DNA marker that behaves similarly to C. difficile spores (ie, prolonged survival on surfaces, inactivation by bleach but not alcohol or quaternary ammonium disinfectants, and removal through mechanical action) to study the potential for dissemination of pathogens from ward to ward. The DNA marker disseminated from portable equipment on 1 ward to other wards when equipment was shared and to a physician work room and to the hospital cafeteria. Contaminated wound care and phlebotomy equipment also disseminated the marker to surfaces on multiple wards.

Our findings have important implications for infection control. First, in investigations of pathogen transmission, routes of dissemination between wards should be considered. Second, there is a need for improved strategies for disinfection of shared equipment. Although our policies recommend cleaning of equipment between patients, only 1 of the 6 inoculated devices was cleaned based on fluorescent marker removal. It is likely that cleaning of equipment between patients performed as recommended in current guidelines would have reduced the frequency of transfer.Reference John, Alhmidi, Cadnum, Jencson and Donskey 7 Finally, hand hygiene is indicated after touching portable equipment. It is likely that the hands of personnel contributed to transfer of the marker from inoculated devices to clean surfaces.

Our study has some limitations. The study was conducted in 1 hospital and the marker was inoculated on 1 ward. Our results are likely to reflect a worst-case scenario because the concentration of the DNA marker applied to equipment was high. Because the DNA marker is not affected by alcohol hand sanitizer, transmission might have been more frequent than would occur with alcohol-susceptible surrogate markers or pathogens. However, widespread dissemination of bacteriophage MS2 has also been demonstrated in a hospital setting.Reference Koganti, Alhmidi, Tomas, Cadnum, Jencson and Donskey 6

In summary, our findings demonstrate the plausibility of pathogen transmission in the absence of shared ward exposure. Future studies are needed to investigate routes and frequency of ward-to-ward transmission of pathogens in healthcare facilities. In addition, there is a need for studies are needed to determine the efficacy of interventions such as improved cleaning of portable equipment.

Acknowledgments

We thank the nursing staff at the Cleveland VA Medical Center for helpful discussions regarding potential routes of pathogen transmission.

Financial support

This work was supported by a Merit Review (grant no. 1 I01 BX002944-01A1) from the Department of Veterans Affairs to C.J.D.

Conflicts of interest

C.J.D. has received research grants from GOJO, Clorox, PDI, Pfizer, Avery Dennison, and Boehringer Laboratories. All other authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.