Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) affects nearly 8,000 hospitalized children in the United States annually.Reference Nylund, Goudie, Garza, Fairbrother and Cohen 1 The rate is rapidly increasing in pediatric hospitals nationwide, and it rose from 20.0 to 31.5 CDIs per 10,000 patients between 2003 and 2009.Reference Nylund, Goudie, Garza, Fairbrother and Cohen 1 , Reference Deshpande, Pant, Anderson, Donskey and Sferra 2 This trend will likely continue as community-acquired CDI becomes more prevalent.

Far less is known about the pathology of CDI in children than adults, and its control is complicated by considerable variability in the natural history of the infection across the pediatric age spectrum. Rates of asymptomatic intestinal colonization in children younger than 2 years old are consistently >10%, even among healthy individuals in the community.Reference Rousseau, Poilane, De Pontual, Maherault, Le Monnier and Collignon 3 , Reference Adlerberth, Huang and Lindberg 4 Unlike in adults and older children, C. difficile colonization at this young age rarely progresses to symptomatic diarrheal infection.Reference Schutze and Willoughby 5 , Reference Jangi and Lamont 6 However, because of their high prevalence of colonization, infants and young children are a potential reservoir for C. difficile transmission.Reference Rousseau, Poilane, De Pontual, Maherault, Le Monnier and Collignon 3 , Reference Hecker, Riggs, Hoyen, Lancioni and Donskey 7 – Reference Stoesser, Crook and Fung 9 Above age 3, a child’s gastrointestinal microbiome composition approximates that of an adult, and C. difficile colonization occurs at a rate similar to young and middle-aged adults.Reference Schutze and Willoughby 5 , Reference Jangi and Lamont 6 , Reference Yatsunenko, Rey and Manary 10

Pediatric hospitals face several unique challenges to preventing C. difficile transmission, including extended patient-to-patient interactions in hospital common areas and extensive family visits. Traditionally, CDI has been considered a problem of adult facilities, and children’s hospitals are not required to track rates of hospital-onset CDI (HO-CDI). Therefore, institution-specific pediatric surveillance data are lacking, and few pediatric studies have evaluated the effectiveness of C. difficile interventions.Reference McFarland, Ozen, Dinleyici and Goh 11

Current Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America recommendations focus primarily on C. difficile prevention in the adult, acute-care setting, and there is little guidance for pediatric infection prevention staff and hospital administrators to follow when deciding which interventions to implement.Reference McDonald, Gerding and Johnson 12 As CDI becomes a more pressing pediatric issue, prioritizing interventions that are highly effective in this specific context has become critical.

Computer-simulation modeling can assess the effectiveness of countless permutations of single and multiple-intervention strategies.Reference Gingras, Guertin, Laprise, Drolet and Brisson 13 , Reference Bonabeau 14 Evaluating interventions by traditional epidemiologic methods would rapidly become time-consuming and cost-prohibitive. Furthermore, infection prevention interventions are typically implemented simultaneously in multiple-intervention bundles.Reference McDonald, Gerding and Johnson 12 , Reference Barker, Ngam, Musuuza, Vaughn and Safdar 15 Observational studies and randomized controlled trials cannot differentiate the individual effects of a single intervention in such a bundle. By modeling counterfactual scenarios, simulation modeling can evaluate the isolated effects of single-intervention strategies.

Agent-based modeling is a type of stochastic simulation in which members of a system are tracked individually and can interact with each other and the environment. By evaluating transmission at the individual level, these models can account for the indirect and downstream effects of seemingly minor changes. Several agent-based and other mathematical models of C. difficile have been used in the adult setting.Reference Gingras, Guertin, Laprise, Drolet and Brisson 13 , Reference Barker, Alagoz and Safdar 16 – Reference Codella, Safdar, Heffernan and Alagoz 18 However, to our knowledge, no C. difficile transmission simulation model exists in the pediatric context. Thus, we developed an agent-based model of C. difficile transmission in a children’s hospital and employed it to evaluate the effectiveness of 9 infection prevention interventions and 6 multi-intervention bundles.

Methods

Approach

We constructed an agent-based simulation model of healthcare-associated C. difficile transmission in an 80-bed, generic, freestanding children’s hospital. The size and characteristics of the generic hospital are based on American Hospital Association data regarding mid-sized facilities 19 ; it does not approximate any specific real-world facility. The hospital is divided into 8 general pediatric wards, each containing 10 single-bed patient rooms, a nursing station, physician workroom, and a multipurpose patient and visitor common area (Fig. 1). All wards are identical, with high-risk specialty populations, such as oncologic, transplant, or gastrointestinal patients, included on the same wards as lower-risk patients. The hospital also contains a central room where all nonisolated patients can visit and older students can attend school.

Fig. 1. The model hospital is an 80-bed facility divided into 8 wards with 10 beds each and a hospital-wide playroom/school.

Agents

The model uses 5 types of agents: patients, visitors, caregivers, nurses, and physicians. All patients are assigned to a specific room and 1 of 3 initial C. difficile states at admission: susceptible to infection, asymptomatically colonized, or actively infected. Every 6 hours each patient has the potential to be recategorized into 1 of 8 C. difficile clinical states, as determined by probabilities in the model’s discrete-time Markov chain (Fig. 2). The Markov chain, representing the progression of CDI in a patient, is recalibrated for the pediatric setting from Markov chains used in prior agent-based C. difficile models for adults (Supplement S2 online).Reference Barker, Alagoz and Safdar 16 , Reference Codella, Safdar, Heffernan and Alagoz 18

Fig. 2. Representations of the discrete-time Markov chain in (A) matrix and (B) transition state diagram form. Patients in the gray states are contagious and can expose others and the environment to C. difficile (thereby, sending affected patients to the exposed state), but patients in the white states cannot. Note. GI, gastrointestinal.

Visitors are assigned 1 patient with whom they spend an average of 15 minutes before leaving the hospital. Caregivers represent parents or guardians, who typically stay with the patient overnight or for several daytime hours, and they are involved in activities such as patient feeding, bathing, and attending school. Among healthcare-worker agent types, nurses work on 1 ward and physicians work hospital-wide. The overall order of model events and flow diagrams of agent logic are included in Supplement S4 (online).

Clostridioides difficile transmission can occur via 14 interactions between agents and the environment (Supplementary Fig. S1 online). The probability of transmission is proportional to the duration of time that contaminated agents interact with each other or the environment. A Bernoulli trial determines the success of transmission at the time each interaction occurs (Supplementary Fig. S2 online). Visitors, caregivers, nurses, and physicians can be exposed to C. difficile and act as a contagious vector to propagate infection. However, these agents cannot become colonized or infected, as the prevalence of C. difficile colonization among healthy healthcare personnel is less than 1%.Reference Friedman, Pollard and Stupart 20

Interventions

We evaluated the comparative clinical effectiveness of 9 interventions and 6 multi-intervention bundles (Table 1). These bundles included a hand hygiene bundle, a sporicidal disinfection bundle, and 4 additive maximum effectiveness bundles that ranged in size from 2 to 5 interventions. All strategies were implemented at the initiation of the model run and continued throughout the entire simulation period. They were applied equally across all patients in the model, regardless of age. Each single intervention was modeled at a typical and ideal implementation level. “Typical” reflects a standard intervention rollout, whereas “ideal” corresponds to optimal implementation conditions, such as strong stakeholder support and leadership buy-in. We also modeled a third implementation level for the visitor contact precautions intervention, consistent with an opt-in–only policy, which corresponded to a 5% compliance rate. All interventions were compared to a baseline control state that reflected standard hospital infection prevention practices prior to active intervention implementation.

Table 1. Modeled Intervention Strategies

Note. ABHR, alcohol based hand rub; HCW, healthcare worker.

a Soap and water hand hygiene is currently recommended by the Infectious Disease Society of America’s C. difficile prevention guidelines only in outbreak and hyperendemic settings.Reference McDonald, Gerding and Johnson12

The multi-intervention bundles were developed in a stepwise process, with typical level interventions added in the order of their single-intervention effectiveness. Two additional bundles, focused on hand hygiene and environmental disinfection, were constructed on the basis of expert opinion as likely implementable intervention combinations.

Parameters

To maximize model generalizability across US children’s hospitals, parameter estimates were derived from the results of >100 peer-reviewed studies (Tables 2 and 3). Primary administrative data from the American Family Children’s Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin, were only used to determine the distribution for patient length of stay and patient transfer intervention estimates because these data were not available from the literature (Supplements S3 and S5 online). Several parameter estimates were based on studies conducted in adult patients because pediatric studies are lacking. However, many such estimates are unlikely to vary appreciably between contexts, such as C. difficile transfer efficiencies. All parameter estimates were reviewed for their applicability in a pediatric setting by the hospital epidemiologist at our children’s hospital before inclusion in the model.

Table 2. Input Parameter Estimates for the Agent-Based Model

Note. EO, expert opinion; SD, standard deviation.

a Unless otherwise specified.

b References in Supplement 1 (online).

c Based on age distribution of nonneonatal hospitalized patients.

d Assumption that 70% of children <15 years old will have an overnight caregiver.Reference Tabak, Zilberberg, Johannes, Sun and McDonald29

e Assumption 90% of children <15 years old will have a daytime caregiver.Reference Tabak, Zilberberg, Johannes, Sun and McDonald29

Table 3. Intervention Parameter Estimates for the Agent-Based Model

Note. ABHR, alcohol-based hand rub; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

a References in Supplement 1 (online).

b Effectiveness at removal of spores.

c Known C. difficile room compliance range based on the range in standard rooms and a standard: CDI hand hygiene noncompliance ratio, 1.34.

d Effectiveness at preventing contamination with spores.

Outcomes

Intervention effectiveness was evaluated by 2 primary outcomes: HO-CDIs per 10,000 patient days and asymptomatic C. difficile colonizations per 1,000 admissions. HO-CDI was defined by symptomatic diarrhea and a positive polymerase chain reaction result on a specimen collected >3 days after hospital admission. 21 Asymptomatic colonization was defined as carriage of C. difficile bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract without clinical symptoms of diarrhea.

Simulation

The model was coded and simulated in NetLogo software version 5.3.1,Reference Wilensky 22 which employs a 5-minute time step. Each run simulates 1 calendar year. We implemented synchronized common random numbers to reduce variance in the results caused by stochastic noise and to allow for direct comparison of the results across counterfactual scenarios (Supplement S6 online).Reference Stout and Goldie 23 Model verification and validation, including sensitivity analyses and cross-validation, are described in Supplement S7 (online).

We simulated 5,000 runs for 6 multi-intervention bundles and 20 single-intervention scenarios: 1 at baseline, 9 with 1 typical-level intervention, 9 with 1 ideal-level intervention, and 1 opt-in–only visitor contact-precautions intervention.

Results

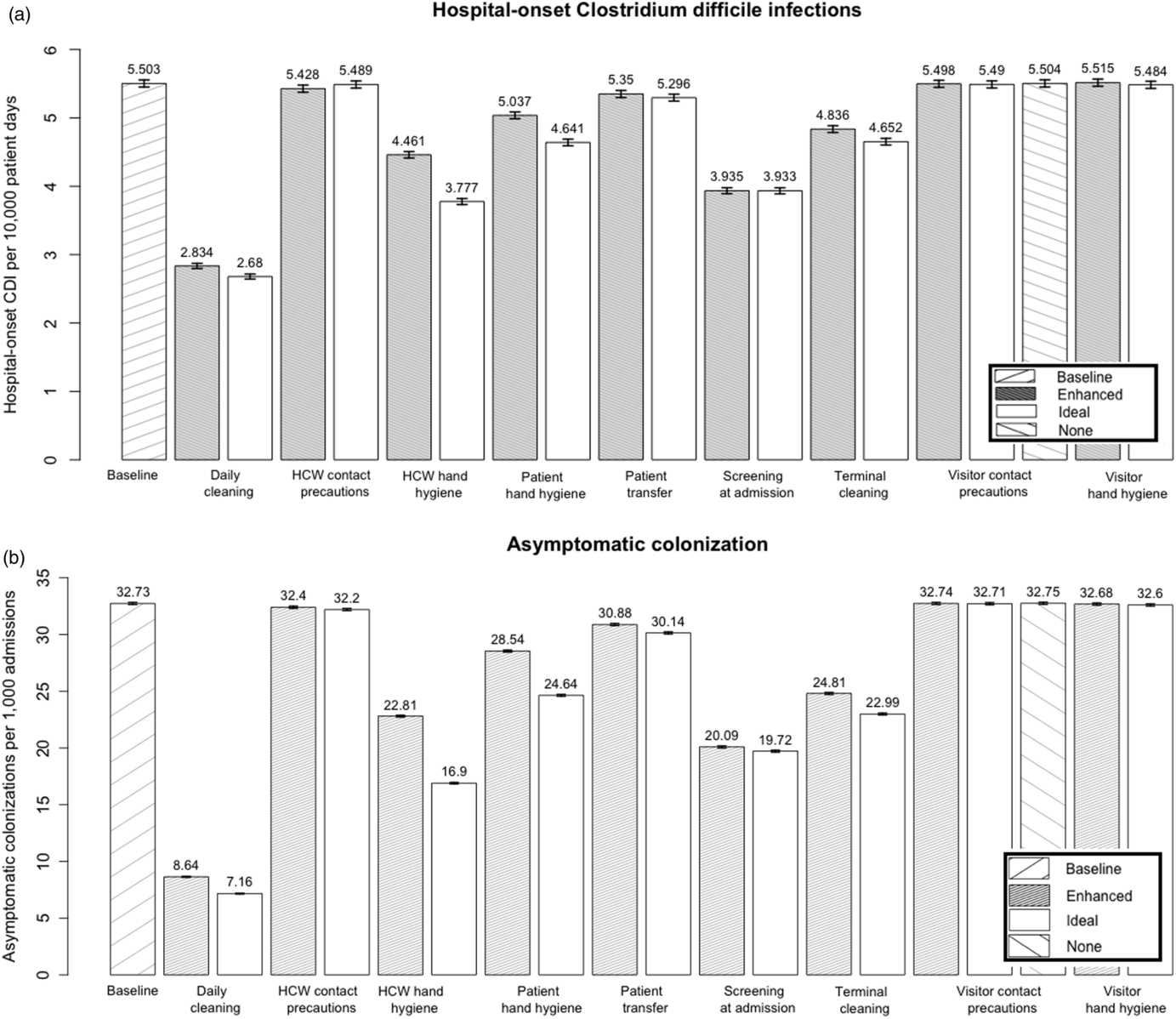

The model predicted that daily disinfection of all hospital rooms with a sporicidal product was the most effective single-intervention typical level strategy for decreasing both HO-CDI (48.5% reduction) and asymptomatic C. difficile colonization (73.6% reduction) (Fig. 3). Screening for asymptomatic intestinal colonization at admission was the second most effective modeled strategy (HO-CDI reduction, 28.5%; colonization reduction, 38.6%). Terminal environmental disinfection, healthcare worker (HCW) and patient hand hygiene, and reducing room transfers also considerably decreased both outcomes.

Fig. 3. Comparative effectiveness of infection prevention interventions at reducing (a) hospital-onset CDIs and (b) asymptomatic colonization.

Modeling HCW hand hygiene at the ideal level resulted in an additional 15.3% overall reduction in HO-CDI. It was 1 of 4 interventions for which the model showed meaningful improvement in HO-CDI prevention when increasing implementation from the typical to ideal level strategies. The other 3 interventions were patient hand hygiene (additional 7.9% reduction), daily disinfection (5.4%), and terminal disinfection (3.8%).

The model predicted that visitor hand hygiene and visitor and HCW contact precautions were not effective at reducing either HO-CDI or asymptomatic colonization. The modeled strategy in which visitor contact precautions were removed from the hospital and used by only 5% of visitors who opted-into the program showed no change in the HO-CDI (95% CI: −0.07 to 0.07) or asymptomatic colonization rate (95% CI, −0.16 to 0.12), compared to the baseline.

We assessed 6 CDI bundles, simulated for 5,000 runs each (Table 4). Adding terminal sporicidal disinfection to daily sporicidal disinfection resulted in no additional reduction in HO-CDI in the model, but it improved the asymptomatic colonization rate over the daily disinfection intervention alone. All bundles reduced HO-CDI and asymptomatic colonization compared to the baseline. The model predicted the most effective 2-intervention bundle included daily disinfection and screening, which reduced HO-CDI by 62.0% and asymptomatic colonization by 88.4%. Adding HCW hand hygiene to the 2-intervention bundle reduced HO-CDI another 1.8%. Increasing this 3-strategy bundle to include 4 and 5 interventions did not further reduce HO-CDI, although it did result in an additional reduction in asymptomatic colonization.

Table 4. Comparative Effectiveness of Intervention Bundles

Note. CI, confidence interval; HCW, healthcare worker; HH, hand hygiene.

The results of the sensitivity analyses are shown in a series of tornado diagrams, which evaluated the impact of changing 6 key input parameters on model conclusions (Supplementary Fig. S2 online). Among these 6 input parameters, person-to-environment and person-to-person transfer efficiency were the most influential parameters affecting model results. Trends among the 3 most effective interventions were stable across variations in parameter estimates, with the exception of the person-to-environment parameter. Using the lowest estimate for person-to-environment transfer efficiency, 29%, screening at admission resulted in a slightly lower HO-CDI rate than daily disinfection. The model underwent limited cross-validation using the 2 existing relevant pediatric infection prevention intervention studies in the literature (Supplement S8 online).

Discussion

An agent-based model predicted that daily sporicidal disinfection and screening at admission was by far the most effective 2-pronged strategy for reducing C. difficile. Combining these interventions potentially enables hospitals to reduce HO-CDI by >60% and asymptomatic colonization by nearly 90%. In terms of implementation, replacing nonsporicidal cleaner with well-tolerated sporicidal products in a daily disinfection intervention would likely encounter fewer barriers than most modeled strategies. The system workflow changes and additional time requirements that this product substitution entails are negligible.Reference Orenstein, Aronhalt, McManus and Fedraw 24 Environmental disinfection interventions have been successful at improving disinfection rates of high touch surfaces in the adult setting, such as bed rails, door handles, and call buttons. 21 , Reference Wilensky 22 , Reference Sitzlar, Deshpande, Fertelli, Kundrapu, Sethi and Donskey 25 – Reference Hess, Shardell and Johnson 27 Daily sporicidal disinfection was also the most effective intervention in our adult hospital agent-based C. difficile model.Reference Barker, Alagoz and Safdar 16 However, unique aspects of environmental disinfection in the pediatrics context must be accounted for in any proposed interventions. Toys are a common source of bacterial pathogens that require disinfection between patients.Reference Moore 28 Future studies should be conducted to determine the movement and sharing of toys between patients and throughout the hospital because this potentially mobile reservoir of disease is not accounted for in traditional conceptualizations of the physical environment.

Implementation of hospital-wide screening would likely receive more initial pushback from front-line providers than daily disinfection. Testing children for C. difficile before age 3 remains controversial, due to their high rate of asymptomatic colonization and the predominance of viral infections as a major cause of diarrhea, and the American Academy of Pediatrics is concerned with overtreatment.Reference Schutze and Willoughby 5 However, in settings in which C. difficile containment has proven challenging, this strategy may be deployed judiciously. Notably, the primary goal of screening is not to reduce colonization in infants and young children themselves, but to reduce hospital-wide morbidity and mortality by interrupting the spread of infectious spores to other hospitalized children. The CDI pathology in children more than 3 years old is similar to that in adults. It has severe and costly consequences, including a longer average hospital length of stay, treatment failure, recurrent infection, and rarely, death.Reference Tabak, Zilberberg, Johannes, Sun and McDonald 29 , Reference Sammons, Localio, Xiao, Coffin and Zaoutis 30 Recent genetic and modeling studies have shown that asymptomatically colonized people are key reservoirs and transmitters of the disease.Reference Rubin, Jones and Leecaster 17 , Reference Eyre, Griffiths and Vaughan 31 These findings are consistent with observational studies that show high levels of skin and environmental contamination among hospitalized, asymptomatic colonized patients.Reference Bobulsky, Al-Nassir, Riggs, Sethi and Donskey 32

Screening at admission could help break the chain of contamination that occurs when healthcare personnel transition from an unknown, contagious, asymptomatically colonized patient to a susceptible patient. This intervention implements soap and water hand hygiene, sporicidal cleansers, and contact precautions for patients who screen positive, but it does not initiate treatment. The single existing hospital-wide study of a nonbundled C. difficile screening intervention reported a 56% reduction in HO-CDI in the adult setting.Reference Longtin, Paquet-Bolduc and Gilca 33 Screening interventions in pediatric hospitals have not yet been reported, and additional work is needed to determine optimal target populations.

In light of the unique epidemiology of C. difficile in infants, it is essential that any screening intervention also be implemented simultaneously with an education component focused on appropriateness of treatment. As with adults, asymptomatic patients who test positive for C. difficile on screening should not receive treatment.Reference Longtin, Paquet-Bolduc and Gilca 33 Thus, inpatient antibiotic prescribing patterns should be carefully tracked and evaluated before and after initiation of a screening intervention. Guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics should be followed if young patients become symptomatic; other causes of diarrhea should be ruled out before CDI is diagnosed and treated.Reference Schutze and Willoughby 5

Neither the visitor contact isolation nor visitor hand hygiene intervention was effective at reducing C. difficile. This finding is consistent with our group’s prior study of visitor interventions in the adult hospital setting,Reference Barker, Alagoz and Safdar 16 even with the addition of caregiver agents in the pediatric model who remain in the hospital 12 hours at a time. Similar HO-CDI rates for the modeled opt-in and baseline visitor contact isolation policies bring into question the benefit from contact precautions among visitors of pediatric C. difficile patients. Contact isolation is associated with increased rates of anxiety and depression in the adult setting.Reference Abad, Fearday and Safdar 34 Yet, physical barriers are likely even more distressing for pediatric patients, who are additionally restricted from playrooms, school, and social interactions that may have significant impact on healing. Careful consideration of these risks and benefits is essential to maintaining visitor contact-isolation practices.

The negligible impact of visitor interventions is likely because a series of low-probability events must occur in the model for a visitor to transmit infection. These events include an initial exposure in which the visitor is contaminated by the patient they are visiting or the environment. It must be followed by a second event, in which the visitor transmits infectious spores from their hands either directly to a patient, or to a patient’s room or common room environment, such as a door knob, water fountain, or elevator button. If the later happens, a third event must occur, in which a susceptible patient is subsequently exposed to the contaminated environment. Unlike healthcare personnel, who come into physical contact with several patients a day, visitors spend most of their time with 1 patient. The risk of direct transmission of C. difficile from visitors to this single patient is minimal, as are the clinical effects of the visitor targeted interventions.

All modeling studies are limited by the data quality and conceptual framework that underpin the model’s logic and parameter estimates. This is the first simulation model of C. difficile transmission in the pediatric setting. We relied heavily on studies conducted in adult hospitals when developing many of our parameter estimates. Behaviors such as intervention compliance may occur at different rates in child and adult contexts. However, in many cases, relevant pediatric-specific studies do not currently exist in the literature. Intervention studies available to cross-validate the model with real-life results are scarce.Reference McFarland, Ozen, Dinleyici and Goh 11 , Reference Barker, Ngam, Musuuza, Vaughn and Safdar 15 Future model development would benefit from additional pediatric-focused work, including general workflow systems analyses and targeted evaluations of ongoing infection prevention interventions.

Several additional simplifications and assumptions should be considered in light of the currently available data in the pediatric setting. Clostridioides difficile susceptibility did not vary based on antibiotic usage, comorbidities, previous hospitalization, nor prior CDI. In part because of this lack of patient heterogeneity, we did not evaluate interventions involving antibiotic stewardship or probiotic use. However, both appear promising in recent pediatric studies.Reference Johnston, Goldenberg, Vandvik, Sun and Guyatt 35 , Reference Yu, Lee, Newland and Goldman 36 We also did not address differences in transmission and virulence between C. difficile strains, instead modeling a generic colonization and infection. All spore transmission was based on physical contact, and air dispersal was not considered. Finally, the physical hospital layout was simplified. All rooms and wards were modeled identically, and potentially unique aspects of C. difficile transmission dynamics and risk profiles in units such as oncology, transplant, and intensive care were ignored. Units with >10 beds or that include non–single rooms may have more shared surfaces, with increased risk of transmission from the environment. The results of this model may not be generalizable to these contexts, and additional spatial considerations should be considered in future pediatric simulation models.

Ultimately, this is the first mathematical model to evaluate C. difficile transmission in the pediatric setting. Our finding of 60% reduction in HO-CDI rates using a 2-pronged daily disinfection and asymptomatic screening bundle is promising, especially given the suspected relative ease of substituting sporicidal for nonsporicidal disinfection products. Because the goal of these interventions is infection prevention, we recommend utilizing them continually, rather than only for outbreak control. These results provide much-needed direction to an infection prevention field lacking the literature and C. difficile–targeted guidelines available in the adult setting. Furthermore, many of the most effective interventions modeled are horizontal approaches to infection prevention that impact transmission of other hospital-associated infections, beyond C. difficile. Thus, these findings ultimately have implications for the control of numerous pediatric infectious diseases.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2020.14

Acknowledgments

This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the US Department of Veterans’ Affairs of the US Government.

Financial support

This study was supported by a predoctoral traineeship from the National Institutes of Health (grant no. TL1TR000429 to A.K.B.). The traineeship is administered by the University of Wisconsin Madison, Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, funded by National Institutes of Health (grant no. UL1TR000427). This study was also supported by the Veterans’ Health Administration National Center for Patient Safety Center of Inquiry in the US Department of Veterans’ Affairs (to N.S.), and this research was also supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health Office of the Director (award no. DP2AI144244).

Conflicts of interest

O.A. has served as consultant to Biovector, a startup company active in the area of infection prevention. None of his consulting work is related to this manuscript and the company has not seen this manuscript. All other authors report no conflicts related to this article.