Candida auris is a rapidly emerging, multidrug-resistant fungus that has caused outbreaks of severe infection in several countries.1–Reference Ruiz-Gaitán, Moret and Tasias-Pitarch4 Difficulties in laboratory identification and lack of information about how best to identify colonized patients and prevent transmission make response to this emerging pathogen challenging.1,2,5

In Canada, the first multidrug-resistant C. auris was reported in 2017.Reference Schwartz and Hammond6 As of October 2019, 5 provinces had reported 24 cases with variable susceptibility (unpublished information, Public Health Agency of Canada).Reference Bharat, Alexander and Dingle7 To date, no program has been implemented for systematic surveillance of C. auris in Canada, and data to inform best practices in microbiology and infection prevention and control (IPAC) remain sparse. The Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program (CNISP), a collaboration between the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Canada, formed a C. auris interest group in January 2018. We surveyed CNISP hospitals to assess preparedness for C. auris.

Methods

A survey with 5 IPAC and 12 microbiology laboratory questions was developed by the interest group and was pilot tested at 3 CNISP hospitals (see Supplementary material). In January 2018, the survey was e-mailed to IPAC and microbiology lead for all 66 CNISP hospitals, which are served by 32 microbiology laboratories. Three reminder e-mails were sent at biweekly intervals. Data were entered and analyzed using Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) or OpenEpi (www.openepi.com).

Results

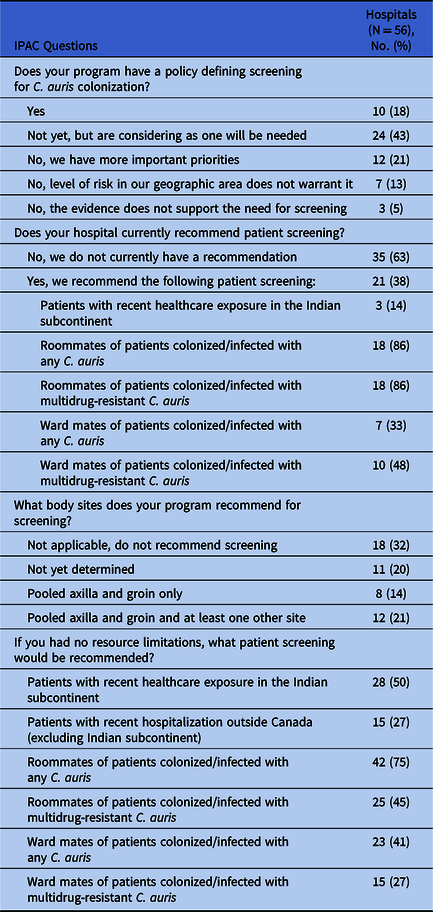

We received completed IPAC surveys for 56 of 66 CNISP hospitals (85%): 23 responses (41%) were from Western Canada (British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba), 21 (38%) were from Central Canada (Ontario, Quebec) and 12 (21%) were from Eastern Canada (the Atlantic provinces). Of 56 hospitals, 10 (18%) had a written policy regarding which patients should be screened for C. auris colonization, and an additional 11 hospitals (20%) recommended some patient screening (Table 1). The most commonly recommended screening (18 of 21 hospitals, 86%) was for roommates of colonized or infected patients. Three hospitals (14%) recommended admission screening of patients who had recently received health care in the Indian subcontinent, although 28 hospitals (50%) would recommend this screening in the absence of resource limitations (Table 1).

Table 1. Infection Prevention and Control Measures Related to Candida auris in Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program (CNISP) Hospitals, 2018

Laboratory surveys were received from 27 of 32 CNISP laboratories (84%). Practices related to identification and susceptibility testing of clinically significant Candida isolates are shown in Table 2. In addition to the identification methods described in Table 2, 26 laboratories (95%) reported that isolates from sterile sites that were not successfully identified to the species level would be sent to a reference lab and/or would be subjected to sequencing for identification. Among these laboratories, 3 reported using PCR and/or sequencing in-house to identify some isolates.

Table 2. Laboratory Practice Related to the Identification and Susceptibility Testing of Candida spp., Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program (CNISP) Hospitals, 2018

a Clinically significant isolates are those for which laboratory standard operating procedures require reporting.

b 1 laboratory reported using API 20 C AUX (bioMerieux, France); 1 used RapID Yeast Plus (ThermoFisher, Walton, MA) and a nonspecified chromogenic agar, 1 used Vitek 2 YST (bioMerieux, France) and did not specify their nonMALDI-TOF MS method.

c Reasons for performing susceptibility testing were request by clinician (n = 9 laboratories), prior antifungal use (n = 2), immunocompromised patients (n = 1), treatment failure (n = 1), isolates from surgical site infections (n = 1), and urine isolates (n = 1). Some laboratories reported >1 reason; 1 did not specify the reason.

Overall, 23 laboratories (85%) reported that susceptibility testing was performed on some Candida isolates identified in their laboratory (Table 2). Of these, 18 laboratories perform some susceptibility testing in-house: 6 by broth microdilution, 2 using gradient strips, 3 using Vitek 2, and 6 by a combination of these with or without disc diffusion testing (1 laboratory did not specify methodology).

When the 27 laboratories were asked about their confidence that a clinically significant isolate of C. auris would be correctly identified in their laboratory, 14 (52%) reported being confident that isolates from sterile sites and nonsterile site isolates resistant to at least 1 antifungal would be correctly identified. Eight laboratories (30%) were confident that isolates from sterile sites but not from nonsterile sites would be correctly identified, and 1 (4%) was confident that resistant isolates, but not susceptible isolates from sterile sites, would be correctly identified. Another 4 laboratories (15%) were not confident in their ability to identify any C. auris. In only 4 of these laboratories would implementing the now available updated Biomerieux Vitek Maldi system, which correctly identifies C. auris, improve C. auris identification.

Three laboratories (11%) reported having a standard operating procedure for processing screening swabs to detect C. auris colonization: 2 laboratories used their own protocol and 1 used the CDC protocol.1 Four laboratories, including 2 of the 3 with standard operating procedures for screening swabs, reported identifying 6 patients infected or colonized with C. auris between 2014 and 2018. Of 6 cases, 4 had isolates from sterile sites: 3 isolates were resistant to fluconazole and 1 was multidrug-resistant. Of 17 responding hospitals served by laboratories that had previously identified C. auris, 16 hospitals recommended some screening for C. auris compared to 5 of 39 other hospitals (P < .001), and 16 of 17 either had or were considering an IPAC screening policy, compared to 15 of 39 other hospitals (P < .001).

Discussion

Despite the identification of multidrug-resistant C. auris in Canada, significant gaps remain in preparedness in CNISP hospitals. Only 18% of hospitals had policies defining which patients should be screened for colonization, and only 14% recommended screening any patients at admission. Although most CNISP laboratories perform or obtain susceptibility testing routinely and are confident in species identification for sterile site isolates, only half of these laboratories have processes that would identify clinically significant C. auris isolated from a nonsterile site specimen, and few have protocols for C. auris colonization detection.

The gaps we identified in IPAC are driven in part by the lack of evidence regarding the epidemiology and burden of disease due to C. auris.Reference Chow, Gade and Tsay3 Despite outbreaks of C. auris infection in numerous countries,1-Reference Ruiz-Gaitán, Moret and Tasias-Pitarch4 few data exist to quantify the risk among patients with a history of hospitalization in these countries or to determine the threshold of risk at which screening should be implemented. Nonetheless, the regular importation of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) from countries with known C. auris risk,Reference Mataseje, Abdesselam and Vachon8 the co-occurrence of CPE and C. auris,Reference Hamprecht, Barber and Mellinghoff9 and the rapid spread of C. auris in hospitals1,Reference Ruiz-Gaitán, Moret and Tasias-Pitarch4 suggest that preparedness is essential. Although evidence shows that our hospitals are responding to the local identification of C. auris, recent US data suggest that waiting for the identification of C. auris in a sterile site prior to defining a response may permit the establishment of substantial local transmission.Reference Karmarkar, O’Donnell and Prestel10

Laboratories are struggling with accurate identification of C. auris and with the development of tests to screen for colonization.1 In 2018, some commonly used organism identification systems did not reliably identify C. auris.5 Although considerable progress has been made in improving identification and in developing screening media since this survey, optimizing the speed of such development requires many laboratories and media suppliers to have access to both isolates and specimens from colonized patients. As new pathogens continue to emerge, further consideration given now to developing global and national processes to optimize laboratory response to novel antimicrobial resistance mechanisms and pathogens could significantly improve future responses.

This survey has several limitations. CNISP hospitals are geographically representative in Canada, but they are predominantly larger teaching hospitals, and preparedness in smaller community hospitals may be different. IPAC and laboratory practices may be different at nonresponding sites and may change over time. The structure of the survey (eg, a limited number of potentially at-risk populations listed in IPAC question no. 1) may have resulted in misinterpretation of opinion or loss of information. Nonetheless, our survey shows that important gaps in IPAC and laboratory preparedness for identifying C. auris patients exist among Canadian hospitals.

CNISP members agreed in 2018 to establish surveillance for C. auris, national IPAC guidelines are in development, and some provinces have issued preliminary guidance5 and/or included C. auris in laboratory proficiency testing.Reference Eckbo, Tang and Roscoe11 How effective these responses will be in protecting our patients from transmission of C. auris in Canadian hospitals remains to be seen.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2019.369

Acknowledgments

We thank all the members of the C. auris interest group, all of the CNISP hospital and laboratory staff who participated in this survey, and the CNISP secretariat for logistical and implementation support.

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest related to this manuscript.