Dentists prescribe ∼10% of outpatient antibiotics, or ∼24.5 million prescriptions annually in the United States.Reference Roberts, Bartoces, Thompson and Hicks1 Antibiotics are primarily prescribed by dentists for the management of bacterial oral infections and for prevention of infective endocarditis.Reference Roberts, Bartoces, Thompson and Hicks1 Currently, data describing the dental prescribing patterns of adjunctive antibiotics with tooth extraction for the treatment of dental infections are limited. In 2019, the American Dental Association released guidelines for the use of antibiotics in the treatment of dental pain and intraoral swelling. However, management of immunocompromised patients and those undergoing tooth extraction is outside the scope of these guidelines.Reference Lockhart, Tampi and Abt2 Although dentists frequently perform extractions for treatment of oral infection, there have been no trials evaluating antibiotic use for this indication.Reference Lodi, Figini and Sardella3

The most common site of odontogenic infection is the dental pulp.Reference Chow4 Acute infection begins with bacterial destruction of the tooth enamel and dentin allowing for invasion of the tooth pulp and progression to abscess formation in the periapical area and alveolar bone. Without intervention, oral infections can spread by direct extension or hematogenously.Reference Chow4,Reference Robertson, Keys and Rautemaa-Richardson5 Treatment of dentoalveolar infections consists of removal of infected pulp or tooth extraction and surgical drainage of abscesses. Often, antibiotics are prescribed as adjunct therapy to prevent infectious complications.Reference Chow4,Reference Robertson, Keys and Rautemaa-Richardson5

As antibiotic overuse contributes to toxicity, pathogenic organism selection, and antimicrobial resistance, the ideal usage of antibiotics in the treatment of dental infections merits further examination.6 Understanding the incidence and risk factors for postextraction infectious complications may assist dental providers to optimally use postextraction oral antibiotics. In this study, we sought to characterize postextraction antibiotic prescribing patterns, predictors for antibiotic prescribing, and the incidence of and risk factors for postextraction oral infection.

Methods

Database

This study was a retrospective analysis of a national cohort of Veterans who underwent tooth extraction(s) in a VA dental clinic from January 1, 2017, to December 31, 2017. Veterans were identified through the Department of Veterans’ Health Administration (VHA) Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW).Reference Price, Shea and Gephart7

Study population

Of all national VA dental clinic encounters between January 1, 2017, and December 31, 2017, a stratified random sample was selected by US Census Bureau region and type of extraction (surgical or nonsurgical) to ensure inclusion of patients in each of these categories. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they received a dental extraction(s) as defined by the American Dental Association (ADA) current dental terminology (CDTs) codes, with codes D7210 and D7250 denoting surgical extractions and D7140 encoding nonsurgical extractions. Only dental extractions performed in a VA dental clinic by a dental provider were included. Dental providers included general dentists and specialty dentists such as periodontists, endodontists, prosthodontists, oral maxillofacial surgeons and dental residents. Patients were excluded if they were prescribed antibiotics for a duration of >14 days from the date of extraction, prescribed antibiotics for a dental encounter by a nondental provider (eg, urgent care or emergency room physician), receipt of an antibiotic for a different indication on the date of the extraction, or receipt of care via a dental phone clinic encounter.

Covariates

Patient demographics, facility location and CDT procedure codes were extracted from the VA CDW. Immunocompromising health conditions, presence of a cardiac diagnosis, prosthetic joint or bone disease, tobacco use history, tooth extraction procedures, antibiotic prescriptions, provider type, surgical time-out documentation, and follow-up information were manually extracted from the health record through electronic chart review. Postextraction antibiotics were defined as antibiotics prescribed by a dentist dispensed on the date of extraction. Cardiac diagnoses included any cardiac comorbidity and were not specific to conditions recommended to receive antibiotic prophylaxis prior to dental visits. Immunocompromising conditions collected included a documented history of diabetes mellitus, active malignancy, human immunodeficiency virus, hematopoietic stem-cell transplant, solid organ transplant and/or an active prescription for an immunosuppressive medication, which included calcineurin inhibitors, mycophenolate, chemotherapy, prednisone ≥20 mg/day (or equivalent) and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. The presence of bone disease was noted if the patient had a documented history of osteoporosis within the health record.

Dental procedure and follow-up notes within 30 days of extraction were also reviewed. Dental procedure notes were reviewed for documentation of adjunctive surgical procedures, including alveoloplasty, tori removal and ostectomy, tooth number(s) extracted and presence of acute infection at time of extraction. Acute infection was defined as documentation of diagnosis of infection by the provider or signs/symptoms of localized infection and/or spreading/systemic infection as reported by the patient and/or provider. Localized signs and/or symptoms of infection included documentation of pain, tenderness or swelling localized to mouth, drainage of pus, or abscess formation. Signs and/or symptoms of spreading or systemic infection documented included fever, cellulitis, difficulty speaking, breathing or swallowing, lymphadenopathy or trismus. Follow-up notes included dental, primary care, urgent care, or emergency department encounters. Follow-up notes were reviewed for documentation of diagnosis of infection by the provider or for signs and/or symptoms of localized infection or spreading or systemic infection and spreading or systemic infection reported by the patient and/or provider as previously described.

Analyses compared patients who received antibiotics to those who did not for the occurrence of a “possible” or “likely” postextraction infection. Patients were categorized as having “possible” postoperative infection if signs and/or symptoms described by the patient or provider were consistent with infection but there was no diagnosis of infection documented in the follow-up note. Patients were categorized as having “likely” postoperative infection if the provider documented an infection diagnosis in the follow-up note. Patients were categorized as “unlikely” to have an infection if there were no signs and/or symptoms or diagnosis of infection documented in the follow-up note or if the patient did not have follow-up as it was assumed that those without infectious signs and/or symptoms would not seek follow-up care.

Statistical analysis

The statistical program SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was utilized for data management and statistical analysis. For the primary outcome of postextraction infection, a 10% baseline risk of infection was utilized based on prior studies to estimate a required sample size of 374 patients, providing the study with an 80% power to detect a difference at a 2-sided significance level of α = 0.05.Reference Lodi, Figini and Sardella3,Reference Braimah, Ndukwe, Owotade and Aregbesola9–Reference Iglesias-Martín, García-Perla-García and Yañez-Vico12 Statistical differences were compared between patients who received antibiotics with dental extraction(s) and patients who did not receive antibiotics with dental extraction(s). Continuous variables were assessed using an independent t test. Categorical variables were assessed using a χ2 and the Fisher exact test. Nonparametric continuous variables were assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Logistic regression analysis was performed to determine predictor variables for antibiotic receipt. Independent variables with a P value <.10 were selected for inclusion in logistic regression analysis. Variables were removed from the models using a backwards selection process until the most parsimonious model was achieved. A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the nationwide cohort of veterans screened from national VA dental encounters in 2017, 69,610 met inclusion criteria, of whom 418 patients were randomly selected. Of the 418 randomly selected patients, 6 were excluded due to receipt of an antibiotic prescription from a nondental provider. Four patients were excluded due to receipt of antibiotics for another indication at time of tooth extraction. Due to technological error with data acquisition, the duplicate dental encounters of 2 patients were excluded. Finally, 1 patient was excluded due to having a planned dental extraction that was aborted and 1 patient was excluded due to unavailability of the electronic health record (Fig. 1). Of the 404 patients included in the study, 154 received an antibiotic dispensed on the date of extraction and the remainder did not receive an antibiotic associated with their extraction.

Fig. 1. Study population.

Baseline demographics are depicted in Table 1. There was no significant difference in age, sex, race, region, tobacco use, presence of immunocompromising condition or presence of cardiac diagnosis, prosthetic joint or bone disease between patients who received antibiotics and patients who did not receive antibiotics. Patients were predominantly male (n = 371, 91.8%) with a mean age of 61.6 years. Compared to those who did not receive postextraction antibiotics, patients who received postextraction antibiotics had a higher incidence of acute infection at the time of extraction (20.8% vs 7.6%; P = .0001), as documented in the electronic health record. Additionally, these patients had a significantly greater number of surgical extractions (P = .023), adjunctive surgical procedures (P = .038), molar extraction (P = .003), and procedures performed by specialty dentist providers (P < .0001). Patients who received postextraction antibiotics also had more teeth extracted (mean, 3.6 ± 3.5 teeth extracted vs 2.2 ± 3.0; P = .0041). In the adjusted multivariable logistic regression model, patients who received postextraction antibiotic prescriptions were more likely to have a greater number of teeth extracted (aOR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.03–1.18), documentation of acute infection at time of extraction (aOR, 3.02; 95% CI, 1.57–5.82), molar extraction (aOR, 1.78; 95% CI, 1.10–2.86) and extraction performed by an oral maxillofacial surgeon (aOR, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.44–3.58) or specialty dentist (aOR, 5.77; 95% CI, 2.05–16.19) (Table 4).

Table 1. Unadjusted Comparison of Veteran Demographics and Dental Visit Characteristics

Note. SD, standard deviation; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; CDT, current dental terminology; IQR, interquartile range.

Finally, more patients who received an antibiotic received follow-up care, as documented by a dental, emergency department, urgent care, or primary care visit within 30 days of extraction compared to those who did not receive an antibiotic (52.5% vs 38.4%; P = .0035). Of the 177 patients who had procedure follow-up, most (n = 173, 97.7%) received care from a dental provider (Table 2).

Table 2. Postextraction Follow-up and Signs and/or Symptoms of Postoperative Infection

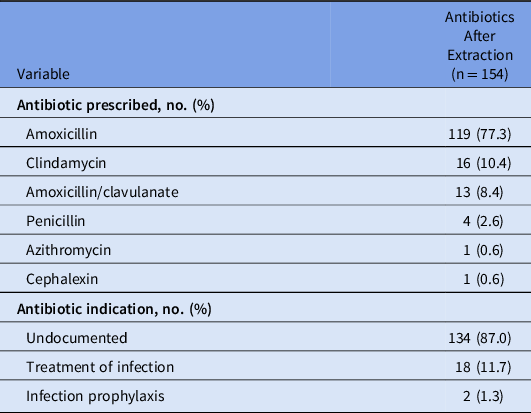

Antibiotic prescribing information is depicted in Table 3. Among patients who received an antibiotic prescribed at the time of procedure to be taken postextraction (n = 154, 38.1%), amoxicillin was most commonly prescribed (n = 119, 77.3%). Most patients (n = 134, 87%) did not have a documented indication for the prescribed antibiotic within the provider notes. Of patients with a documented antibiotic indication, 18 received antibiotics for an infection and 2 received antibiotics for infection prophylaxis.

Table 3. Antibiotics Prescribed to Patients Receiving Tooth Extractions

Primary outcome analysis

For the primary outcome of postextraction oral infection, there was no difference between groups. A possible or likely postextraction oral infection occurred in 4.5% (n = 7) of patients who received an antibiotic compared to 3.2% (n = 8) of patients who did not receive an antibiotic (P = .5898) (Table 5). Multivariate regression could not be performed to determine risk factors for postextraction infection due to the primary outcome occurring at a low frequency. Stratifying our results by the presence or absence of an acute infection at the time of extraction did not change the results (Table 5).

Table 4. Adjusted Analysis of Variables Associated With Receipt of an Antibiotic in Veterans Receiving Tooth Extractions

Note. CI, confidence interval.

Table 5. Frequency of Postextraction Infection (Primary Outcome) Stratified by the Receipt of an Antibiotic

Discussion

The results of the present study indicate that postextraction oral infection was not significantly different among patients who did and did not receive an adjunctive antibiotic prescription. In addition, postextraction infectious complications occurred infrequently among both study groups, despite 37.3% of patients having a documented diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, which has generally been demonstrated to slow wound healing and increase risk of infection.Reference Barasch, Safford, Litaker and Gilbert13 However, there have been no published studies examining oral wound healing after dental procedures in this population.Reference Barasch, Safford, Litaker and Gilbert13

Previous studies examining adjunctive antibiotic use in tooth extraction are primarily limited to medically healthy patients undergoing third molar extraction. A Cochrane review indicated that antibiotic prophylaxis for the extraction of third molars may reduce risk of infection, dry socket, and pain in healthy patients.Reference Lodi, Figini and Sardella3 It is unclear, however, whether this information is generalizable to patients with comorbid disease states, extraction of teeth other than third molars, or tooth extraction for the treatment of severe caries or periodontitis.Reference Lodi, Figini and Sardella3 The present study is the first to our knowledge that examines adjunctive antibiotic use in non–third molar extraction and includes patients with comorbid diseases.

Several predictors were identified for receipt of an antibiotic prescription. Patients were more likely to receive an adjunctive antibiotic prescription with an increasing number of teeth extracted, extraction of molars, documentation of acute infection at time of extraction and if the procedure was performed by an oral maxillofacial surgeon or specialty dentist. However, given that postextraction infection occurred at a low incidence, risk factors for its occurrence could not be identified. Therefore, it is unclear whether risk factors for antibiotic receipt also equate to risk factors for the development of postextraction infectious complications.

Given the results of this study, antibiotic prescribing for tooth extraction may be a potential area of focus for outpatient antimicrobial stewardship efforts. This idea is supported by the finding that 87% of antibiotic prescriptions did not have a documented indication in the medical chart. Accurate documentation of antibiotic indication is essential to evaluate appropriate antibiotic use.Reference Ray, Tallman and Bearden14,Reference Sanchez, Fleming-Dutra, Roberts and Hicks15 This documentation is especially pertinent given that high rates of inappropriate prescribing of periprocedural antibiotics within dentistry has previously been demonstrated.Reference Suda, Henschel and Patel8 Furthermore, documentation of antibiotic indication allows for targeted antimicrobial stewardship interventions such as audit and feedback or provider education.Reference Ray, Tallman and Bearden14 These methods have previously been shown to be effective in reducing inappropriate antibiotic prescribing and improving the accuracy of agent and dose selection within dentistry.Reference Chate, White and Hale17–Reference Gross, Hanna, Rowan, Bleasdale and Suda19 Finally, necessitating documentation of antibiotic indication may lead to lower rates of inappropriate prescribing in the outpatient setting, as previously illustrated among primary care clinicians.Reference Meeker, Linder and Fox16

The present study has several limitations. First, it had a retrospective, nonrandomized design. Additionally, dental and medical care received outside of a VA facility could not be captured in data collection. Furthermore, the postextraction infection rates identified herein were lower than previous studies which provided a basis for power calculations. Thus, it is plausible that this study was underpowered to detect a difference in the primary outcome. Although there are several limitations, this study provides rationale for conducting large, prospective, trials to more clearly define the role of adjunctive antibiotics in tooth extractions for periodontitis and dentoalveolar infections, especially in patients with comorbidities.

In conclusion, infectious complications occurred at a low incidence among patients undergoing tooth extraction with and without adjunctive postprocedure antibiotics. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine antibiotic prescribing patterns and infectious outcomes in patients undergoing non–third molar tooth extraction. Given that antibiotic indication was poorly documented in the health record, antibiotic prescribing for tooth extraction may be a potential area of focus for outpatient antimicrobial stewardship efforts. The results of this study suggest that postprocedural antibiotics may play a limited role in tooth extraction; however, larger retrospective or prospective trials are necessary to more clearly elucidate the role of adjunctive antibiotics. Further research in this area will allow for targeted antimicrobial stewardship interventions to promote judicious antimicrobial prescribing within dentistry.

Acknowledgments

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or the policy of the Department of Veterans’ Affairs or the US government.

Financial support

This work was supported by funding from the Veterans’ Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development Service Investigator Initiated Research Award (grant no. HX002452).

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.