Surgical-site infections (SSIs) are among the most common healthcare-associated infections in the United States. Reference Magill, O’Leary and Janelle1 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention SSI guidelines recommend against the use of prophylactic antibiotics in clean surgeries after the surgical incision is closed, even in the presence of surgical drains, due to lack of evidence for benefit. Reference Berrios-Torres, Umscheid and Bratzler2 In contrast, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons guidelines for breast implant reconstruction recommend that prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis be left to surgeon preference when surgical drains are present. Reference Alderman, Gutowski, Ahuja and Gray3 In practice, up to 70% of plastic surgeons continue prophylactic antibiotics after discharge after mastectomy with breast reconstruction. Reference Phillips, Wang and Mirrer4,Reference Brahmbhatt, Huebner and Scow5

Although postdischarge prophylactic antibiotics are common after mastectomy with breast reconstruction, evidence for its effectiveness in preventing SSI is inconsistent. Several studies have reported decreased risk of SSI with postdischarge prophylactic antibiotic use after mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction Reference Clayton, Bazakas, Lee, Hultman and Halvorson6–Reference Holland, Lentz and Sbitany9 and without. Reference Edwards, Stukenborg, Brenin and Schroen10 However, these studies have limitations, including data from single surgeons, comparing 2 surgeons with differing prescribing practices, and regression to the mean due to high SSI rates prior to change in antibiotic use. Reference Olsen, Nickel and Fox11 Conversely, numerous studies demonstrated no effect of postdischarge antibiotics on SSI following mastectomy, although many of these studies lacked sufficient power to detect an association with only a moderate effect. Reference Liu, Dubbins, Louie, Said, Neligan and Mathes12–Reference Yamin, Nouri and McAuliffe21

Exposure of patients to prolonged antibiotic regimens results in higher costs, selection of antibiotic-resistant organisms, and increased risk of Clostridioides difficile infection. Reference Harbarth, Samore, Lichtenberg and Carmeli22–Reference Balch, Wendelboe, Vesely and Bratzler26 The importance of outpatient antibiotic stewardship is increasingly recognized because outpatient antibiotic prescriptions constitute the majority of antibiotic use. Therefore, outpatient stewardship interventions may have greater potential to decrease the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant organisms than inpatient efforts. Reference MacFadden, Fisman, Hanage and Lipsitch27

To better understand the impact of prolonged prophylactic antibiotics, we aimed to determine (1) the prevalence and factors associated with postdischarge prophylactic antibiotic use and (2) whether postdischarge prophylactic antibiotic use was associated with decreased SSI risk after mastectomy with and without immediate breast reconstruction using a large database of US commercially insured persons.

Methods

We established a cohort of adult women aged 18–64 years who underwent mastectomy between January 1, 2010, and June 30, 2015, using the IBM® MarketScan® commercial database (IBM, Armonk, NY). The 2010–2015 commercial database includes medical and outpatient pharmacy claims for >100 million persons covered by employer-sponsored and commercial health plans. This study was considered exempt from oversight by the Washington University Human Research Protection Office.

Women undergoing mastectomy were identified based on current procedural terminology or International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) procedure codes for mastectomy (Appendix Table 1 online). We implemented additional measures to verify that mastectomy was performed and to identify the date of the procedure (see Appendix online), as described previously. Reference Nickel, Wallace, Warren, Mines and Olsen28

We applied additional exclusions for complicated admissions, procedures in which postdischarge antibiotics were not possible or could have been used for therapeutic indications (Fig. 1). Exclusions during the index surgical admission included death and additional surgery other than mastectomy, using the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) procedure list. 29 To exclude patients who may have received antibiotics due to a recent or current infection, mastectomies were excluded in women with an ICD-9-CM diagnosis code for a systemic or serious (ie, septicemia) or minor (eg, upper respiratory) infection (Appendix Table 2 online).

Fig. 1. Flow diagram with exclusion criteria to establish population of mastectomy procedures among women aged 18–64 years from January 2010 through June 2015 in the MarketScan Commercial Database. *Excluded procedures lacking claims from both a surgeon and facility, if also without supporting evidence for surgery (ie, operating room services, pathology, breast reconstruction, anesthesiology claims), procedures only coded by a provider in outpatient surgery encounter if no facility claims within ±1 day, and procedures without evidence of performance in a hospital (inpatient or outpatient surgery) or ambulatory surgical center. **Excluded for major infection coded in the 30 days prior through 2 days after discharge and minor infection coded in the 14 days prior through 2 days after discharge.

The population was restricted to women with known US region of residence and continuous medical and prescription drug insurance enrollment from 365 days before through 90 days after mastectomy to assess comorbidities, complications, and postdischarge antibiotic use.

Identification of exposures, outcomes, and covariates

The primary exposure of interest was postdischarge prophylactic antibiotic, defined as a paid prescription filled between 15 days before the mastectomy encounter through 2 days after discharge (Appendix Table 3 online). Prescriptions filled in the 15 days prior to mastectomy were considered prophylactic, based on the median time of 15 days between the last plastic-surgeon clinic encounter and mastectomy admission. If a patient had an antibiotic prescription in the period during which prophylactic antibiotics were used that was the same as a filled antibiotic prescription in the 30–16 days prior to the mastectomy encounter, it was not considered prophylactic. We analyzed both any use and category based on antibiotic activity (Appendix Table 3 online).

Comorbidities were identified in the year before surgery, primarily based on the Elixhauser classification, with calculation of the 30-day readmission score. 30,Reference Klabunde, Potosky, Legler and Warren31 Prescription drug claims were used to increase the sensitivity of identification of diabetes and smoking (Appendix Table 1). Prior antibiotics included paid prescriptions filled in the 16–30 days prior to the mastectomy admission.

All analyses were stratified by reconstruction because of differences in the patient populations and SSI risk. The primary outcome of interest was SSI from 2 to 90 days after mastectomy, identified using ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes during inpatient and/or nondiagnostic outpatient encounters (Appendix Table 4 online). Censoring was implemented for subsequent surgical procedures within 90 days using codes defined by the 2015 NHSN procedure list. 29 Censoring was not performed if the subsequent procedure was a breast surgery coded for SSI or if the SSI was coded using a breast-specific code (eg, implant infection). Reference Nickel, Wallace, Warren, Mines and Olsen28

Statistical analyses

Bivariate comparisons were performed using χ2 tests for binary variables and Mann-Whitney U or Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous variables. Independent factors associated with postdischarge prophylactic antibiotics and for SSI were identified with generalized linear models, with calculation of relative risks and robust standard errors. Variables with P < .20 in bivariate analysis or with clinical or biologic plausibility were included in the initial models, with the exception of postdischarge prophylactic antibiotics (primary exposure in the SSI model). Variables were removed in a backward stepwise manner with P < .10 the threshold for retention. Potential multicollinearity of independent variables was assessed using variance inflation factors and model discrimination with the C statistic. Reference Cook32

To assess the clinical impact and robustness of associations between postdischarge prophylactic antibiotics and SSI risk, we calculated the number needed to treat and E-value, respectively. The E-value is the minimum relative risk that a potentially unmeasured confounder would have to have with both the outcome and primary exposure, after controlling for covariates, to account for the observed association between the primary exposure with the outcome. Reference VanderWeele and Ding33 All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Post-hoc tests to determine the power to detect a 50% and 25% difference in SSI incidence depending on utilization of postdischarge oral antibiotics were performed using Power Analysis and Sample Size (PASS) version 14 software (NCSS, Kaysville, Utah).

Results

In total, 80,692 mastectomy procedures were identified among women aged 18–64 years between January 1, 2010, and June 30, 2015. After excluding 41,899 surgical encounters (Fig. 1), the final study cohort included 38,793 mastectomies, of which 24,818 (64.0%) included immediate breast reconstruction (Table 1). Among these, 21,755 breast reconstruction procedures (∼88%) involved a breast implant. For patients with mastectomy plus immediate reconstruction, the median age was 50 years and 9.7% resided in a rural area. Among mastectomy-only encounters, the median age of patients was 55 years and 18.4% resided in a rural area.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Commercially Insured Mastectomy Population

a Rural residence was defined as residing outside of a metropolitan statistical area.

Prophylactic antibiotics were prescribed after discharge after 2,688 mastectomy-only procedures (19.2%) and 17,807 mastectomy plus reconstruction procedures (71.8%) (Table 1). Postdischarge prophylactic antibiotic use ranged from 18.9% in 2013 to 19.7% in 2015 after mastectomy only and 68.2% in 2010 to 74.4% in 2015 after mastectomy plus reconstruction. Antibiotics with anti–methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) activity were most common, accounting for 70.3% and 72.8% among those with postdischarge prophylactic antibiotics after mastectomy only and mastectomy plus reconstruction, respectively. The most commonly prescribed postdischarge prophylactic antibiotics were cephalexin (56.8%), ciprofloxacin (8.0%), and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (7.4%) after mastectomy only and cephalexin (57.9%), cefadroxil (10.6%), and clindamycin (8.2%) after mastectomy plus reconstruction (Appendix Table 3 online).

Results of bivariate analyses for factors associated with postdischarge prophylactic antibiotic receipt stratified by immediate reconstruction are shown in Appendix Table 5 (online). In multivariable analysis, the risk of a filled prescription for a postdischarge prophylactic antibiotic after mastectomy only was significantly higher for women with diabetes, prior S. aureus infection, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and those with a surgical complication during the index admission (Table 2). Women living in a rural area, with neurological disorders, and of older age were significantly less likely to fill a postdischarge prophylactic antibiotic prescription. Among mastectomy plus reconstruction, implant-based surgery was independently associated with 44% increased risk of a postdischarge prophylactic antibiotic prescription (Table 3). Other independent risk factors for prophylactic postdischarge antibiotic after mastectomy plus reconstruction were residing in the Northeast or West regions of the United States, valvular heart disease, and more recent years of surgery. Women who smoked, lived in a rural area, or who had a neurological disorder, depression, or pulmonary circulation disease were significantly less likely to fill a postdischarge prophylactic antibiotic prescription.

Table 2. Patient and Operative Factors Independently Associated With Receipt of Postdischarge Prophylactic Oral Antibiotics After Mastectomy Only in Multivariable Analysis

Notes. CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk. C-statistic = 0.54.

a Also adjusted for age as a continuous variable. Variables entered into model, but not retained: fluid and electrolyte disorders, psychoses.

b Rural residence was defined as residing outside of a metropolitan statistical area.

Table 3. Patient and Operative Factors Independently Associated with Receipt of Postdischarge Prophylactic Oral Antibiotics After Mastectomy Plus Immediate Reconstruction in Multivariable Analysis

Note. CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk. C-statistic = 0.61.

a Also adjusted for age using a spline (3 knots). Variables entered into model but not retained: smoking proxy, obesity, Staphylococcus aureus infection prior year, neoadjuvant chemotherapy prior 60 d, anemia prior 30 d, chronic blood loss anemia, hypertension

b Rural residence was defined as residing outside of a metropolitan statistical area.

The 90-day incidence of SSI was 3.5% after mastectomy only and 8.8% after mastectomy plus immediate reconstruction (Table 1). Among those with mastectomy only, the incidence of SSI was 3.2% among women who filled a prescription after discharge compared to 3.6% among women who did not fill a prophylactic antibiotic prescription after discharge (P = .334). Among those with mastectomy plus immediate reconstruction, the incidence of SSI was 8.3% among women filling a prescription after discharge compared to 9.9% among women who did not fill a postdischarge prophylactic antibiotic prescription (P < .001). The lowest SSI incidence after both mastectomy only and mastectomy plus reconstruction was detected in women who filled a prescription for an anti-MSSA antibiotic after discharge (2.7% and 7.8%, respectively).

The results of bivariate analyses for factors associated with SSI are shown in Appendix Tables 5 and 6 (online). In multivariable analysis, postdischarge anti-MSSA prophylactic antibiotics were independently associated with decreased SSI risk after mastectomy only (relative risk [RR], 0.74; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.55– 0.99) (Table 4). Prophylactic anti-MRSA antibiotics and quinolones were not associated with SSI risk. Independent risk factors for SSI after mastectomy only included diabetes, psychoses, and obesity. For the observed adjusted RR of 0.74 for anti-MSSA prophylactic antibiotics, the E-value was 2.04 for the point estimate, with a lower limit of 1.11. Based on the adjusted RR of 0.74, 107 women would need to be treated with an anti-MSSA antibiotic after discharge after mastectomy only to prevent 1 additional SSI.

Table 4. Patient and Operative Factors Independently Associated with Surgical Site Infection after Mastectomy Only in Multivariable Analysis

Notes. CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk. C-statistic = 0.63.

a Also adjusted for age using a spline (3 knots). Variables entered into model but not retained: anemia prior 30 d, index complication, rheumatoid arthritis or collagen vascular disease, year of surgery.

b Rural residence was defined as residing outside of a metropolitan statistical area.

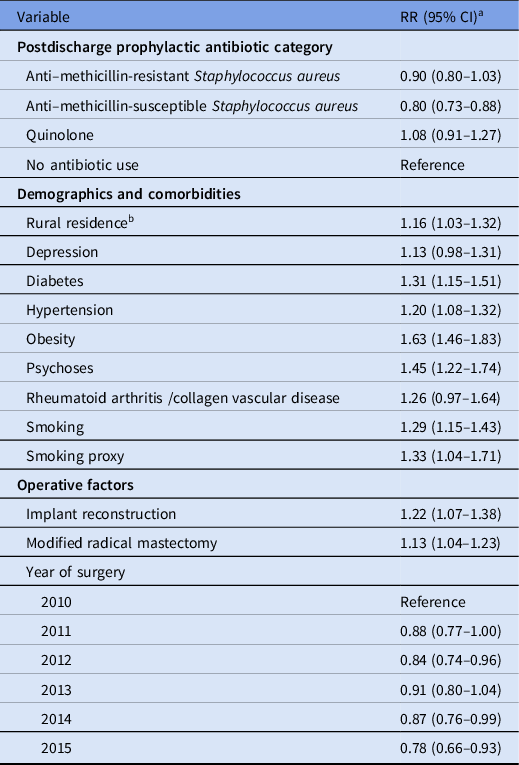

In multivariable analysis, postdischarge prophylactic antibiotics with anti-MSSA activity were independently associated with decreased SSI risk after mastectomy plus immediate reconstruction (RR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.73–0.88) (Table 5). Prophylactic anti-MRSA antibiotics and quinolones were not associated with decreased SSI risk. Other independent risk factors for SSI after mastectomy plus reconstruction included diabetes, psychoses, obesity, and smoking. For the observed adjusted RR of 0.80 for anti-MSSA prophylactic antibiotics, the E-value was 1.81 for the point estimate and 1.53 for the lower bound. Based on these results, 48 women would need to be treated with anti-MSSA postdischarge prophylactic antibiotics after mastectomy plus reconstruction to prevent 1 additional woman from developing an SSI.

Table 5. Patient and Operative Factors Independently Associated with Surgical Site Infection after Mastectomy with Immediate Reconstruction in Multivariable Analysis

Note. CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk. C-statistic = 0.60.

a Also adjusted for age using a spline (5 knots). Variables entered into model, but not retained: index complication, patient residence region, hypothyroidism, liver disease, other neurological disorders, peripheral vascular disease, pulmonary circulation disease, valvular disease.

b Rural residence was defined as residing outside of a metropolitan statistical area.

Discussion

In this analysis of commercially insured women, we found that postdischarge prophylactic antibiotics were used in >70% of women with immediate reconstruction and in 19% after mastectomy only. Factors associated with utilization after mastectomy only included history of S. aureus infection, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and a noninfectious wound complication during the mastectomy admission. In the reconstruction population, the most influential factor associated with utilization of prophylactic postdischarge antibiotics was implant reconstruction, with slightly increased antibiotic use over the study period. In multivariable analyses slightly decreased risk of SSI was found in women who filled a prescription for a prophylactic antibiotic with anti-MSSA activity after both mastectomy only and mastectomy plus reconstruction.

The utilization of continued oral prophylactic antibiotics we report is consistent with the results of our prior multicenter study in which 35% of women after mastectomy only and 85% after mastectomy plus reconstruction were given an antibiotic prescription at discharge in the absence of evidence for infection. Reference Warren, Nickel and Hostler17 The variation in prophylactic antibiotic utilization in our prior study was largely driven by individual surgeons and by study site, rather than by patient factors. Reference Warren, Nickel and Hostler17 In our current study, prolonged prophylactic antibiotic utilization was also likely driven largely by individual surgeons and institutions because the discriminative ability of the multivariable models to identify patient-level factors associated with postdischarge prophylactic antibiotics use was poor. Because no facility or provider information is available in the MarketScan database, we were unable to directly assess associations with individual providers.

Most prior studies of continued prophylactic antibiotics after mastectomy plus immediate reconstruction showed no decreased risk of SSI, although the single-center studies in the literature and our prior multicenter study were underpowered to address risk of SSI specifically. Reference Olsen, Nickel and Fox11,Reference Warren, Nickel and Hostler17 More recently, 2 adequately powered studies using administrative claims data showed no association of continued prophylactic antibiotics with decreased SSI risk after mastectomy plus reconstruction. Reference Olsen, Nickel, Fraser, Wallace and Warren18,Reference Ranganathan, Sears and Zhong19

Only 2 prior studies have evaluated postdischarge prophylactic antibiotic use in the mastectomy-only population. The study by Edwards et al Reference Edwards, Stukenborg, Brenin and Schroen10 is subject to confounding bias because surgeries were performed by 2 surgeons, with one utilizing only preoperative antibiotics and the other continuing antibiotics after discharge. Reference Edwards, Stukenborg, Brenin and Schroen10 The other study was our prior multicenter study, in which we did not find evidence for benefit of postdischarge prophylactic antibiotics, although it was underpowered to detect an association with SSI (power, 0.28). Reference Warren, Nickel and Hostler17

In contrast to prior studies, our current study focused on SSI risk associated with specific categories of prophylactic antibiotics. Although MRSA is a relatively uncommon etiology in postmastectomy breast infections, most organisms isolated from breast infections, particularly after implant reconstruction, are resistant to first-generation cephalosporins and similar narrow-spectrum anti-MSSA antibiotics. Reference Banuelos, Abu-Ghname, Asaad, Vyas, Rizwan and Sharaf34,Reference Viola, Baumann and Mohan35 In a recent study comparing the microbiology of SSIs after mastectomy with tissue expander reconstruction in women treated with postdischarge prophylactic antibiotics versus only perioperative antibiotics, Monroig et al Reference Monroig, Ghosh and Marquez36 found no difference in the incidence of SSI but more diverse etiology in women treated with postdischarge prophylaxis, including more gram-negative bacteria and fewer S. aureus infections. Although Monroig et al found no evidence for benefit of prolonged postdischarge antibiotics, prolonged oral therapy may be associated with harm due to selection of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Reference Monroig, Ghosh and Marquez36

Interestingly, we found decreased SSI risk among women who filled a prescription for antibiotics with anti-MSSA activity but not with anti-MRSA antibiotics or quinolones. In the mastectomy plus reconstruction population, we had >80% power to detect a 25% decrease in SSI risk for all 3 categories of postdischarge antibiotics, but we lacked sufficient power in the mastectomy-only population (power, 0.21 for anti-MRSA antibiotics and 0.17 for quinolones). Although in multivariable analysis anti-MSSA antibiotics were associated with decreased risk of SSI compared to no postdischarge antibiotics, the lower bounds of the E-value were only 1.11 (mastectomy only) and 1.53 (mastectomy plus reconstruction). The E-value represents the relative risk of an unmeasured confounder that would explain the treatment-outcome result (ie, reduced risk of SSI associated with anti-MSSA postdischarge antibiotics). The lower bound of the E-value represents the relative risk of an unmeasured confounder that would negate the significance of the adjusted treatment-outcome result. For mastectomy only an unmeasured confounder with a RR of 1.11 would alter the findings such that anti-MSSA prophylactic antibiotic therapy would no longer be significantly associated with decreased SSI risk. Similarly, an unmeasured confounder with a RR of 1.53 would result in a nonsignificant association of anti-MSSA antibiotics with decreased SSI risk after mastectomy plus reconstruction. Given the inability to identify some important predictors of SSI (eg, glucose control) or to accurately capture others (eg, obesity, smoking) with claims data, such unmeasured confounders may exist which could account for the slightly decreased risk of SSI associated with anti-MSSA antibiotics.

In this study, we found that 107 women would need to be treated with an anti-MSSA antibiotic after discharge to prevent 1 additional SSI after mastectomy only and that 48 women would need to be treated after mastectomy plus reconstruction to prevent 1 additional infection. The relatively small benefit associated with postdischarge anti-MSSA antibiotics needs to be balanced against the harms of unnecessary antibiotic utilization, given the substantial numbers needed to be treated. Antibiotics with anti-MSSA activity are associated with moderate risk of C. difficile infection, Reference Brown, Khanafer, Daneman and Fisman37 and other adverse events, ranging from more common minor (eg, rash) to more rare serious complications (eg, anaphylaxis or acute renal failure). Reference Geller, Lovegrove, Shehab, Hicks, Sapiano and Budnitz38

This study has several limitations. These findings have the potential for both unmeasured confounding and incomplete capture of some risk factors, as described above. We attempted to mitigate the incomplete capture of obesity and smoking by requiring only a single diagnosis code, which increases the sensitivity of identification of these conditions. Reference Nickel, Wallace and Warren39 When possible, we used medications in addition to diagnosis codes to improve the sensitivity of detection of other important risk factors. Reference Nickel, Wallace and Warren39–Reference Carrara, Scirè and Zambon42 Other variables, such as prior S aureus infection, might be underestimated by coding data. Misclassification of therapeutic antibiotics as prophylactic may have been possible if an infectious diagnosis was not recorded at the time of the prescription. However, we used strict criteria, including exclusion for a variety of perioperative infections within 30 days of surgery, to mitigate this misclassification. Lastly, our study was limited to nonelderly, privately insured women, so these results may not be generalizable to the uninsured, Medicaid, or Medicare populations.

The strengths of our study include the very large size of the cohort, which resulted in >90% power to detect a 25% difference in SSI incidence with use of postdischarge prophylactic antibiotics. We used a detailed methodologic approach combining careful patient selection and follow-up with rigorous statistical analyses to determine the effect of postdischarge prophylactic antibiotics on risk of SSI. We studied the use and impact of specific categories of commonly used oral antibiotics, which allowed us to separate the effects of antibiotics based on microbial activity.

We used a large commercial claims database to determine factors associated with use of postdischarge prophylactic antibiotics in nonelderly women after mastectomy only and mastectomy plus immediate reconstruction and 90-day SSI risk. The use of postdischarge antibiotics did not appear to be driven by patient risk factors but rather by physician preference. Antibiotics with anti-MSSA activity were associated with a small but significantly decreased risk of 90-day SSI after both mastectomy only and mastectomy plus reconstruction. The small apparent benefit of postdischarge oral antibiotics should be balanced with the risks associated with overuse of antibiotics, particularly given the relatively large number of women who would need to be treated to prevent one infection.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2021.400

Acknowledgments

Financial support

Funding for this project was provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (grant no. U54CK000482 VJF). The Center for Administrative Data Research is supported in part by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences (grant no. UL1 TR002345) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ grant no. R24 HS19455). The funding sources were not involved in the conduct of the study.

Conflicts of interest

M.A.O. reports consultant work and grant funding from Pfizer outside the submitted manuscript. V.J.F. reports that her spouse is the Chief Clinical Officer at Cigna Corporation. D.K.W. reports consultant work with Centene, PDI, Pursuit Vascular, and Homburg & Partner, and he is a subinvestigator for a Pfizer-sponsored study for work outside the submitted manuscript. All other authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.