Hospital-acquired (HA) bacteremia is one of the most common hospital-acquired infections (HAIs). A systematic review estimated 1,200,000 episodes of bloodstream infections per year in Europe as well as 157,000 related deaths.Reference Goto and Al-Hasan 1 HA bacteremia is estimated to occur 312,822 times per year across acute-care hospitals. 2

Because continuous manual surveillance of HAIs is laborious and costly, point prevalence studies (PPSs) were introduced. In Denmark, PPSs have been performed twice a year since 2009 in hospitals that volunteer to do so. Between 2010 and 2014, the median prevalence of HA bacteremia was 1.1% overall (range, 1.1%–1.6%) and 20.4% in intensive care units (ICUs; range, 12.8%–31.9%). 3 However, PPSs are difficult to standardize because of interobserver and intraobserver variations.Reference Lin, Hota and Khan 4 , Reference Mayer, Greene and Howell 5 Several Danish initiatives have explored the possibilities of electronic surveillance, either semiautomated combined with manual components, or fully automated.Reference Leth and Møller 6 – Reference Redder, Leth and Møller 9 An international systematic review indicated great promise for electronic surveillance.Reference Leal and Laupland 10 Based on these studies, we developed an algorithm for HA bacteremia for use in the national automated surveillance that provides continuous incidence data for all Danish hospitals: the Danish Hospital-Acquired Infections Database (HAIBA). HAIBA has been publicly available since March 2015. 11

On a local level, a variety of data sources may be available for electronic surveillance that allow the use of complex algorithms and/or additional manual evaluations, including analyses of administrative, microbiological, and biochemical data, as well as medical records. However, not all local settings have access to all these sources nor resources for continuous manual evaluation. On a national level, fully automated systems with few data sources may be more feasible. However, potential differences in registration and utilization practices need to be accounted for. An earlier article described an analysis of blood culture utilization across Departments of Clinical Microbiology (DCMs) in Denmark and indicated the feasibility of such surveillance.Reference Gubbels, Nielsen and Voldstedlund 12

The objectives of the present article were (1) to describe the data sources and algorithm created for HA bacteremia, (2) to determine its concordance with the traditional way of monitoring HAIs (ie, PPS), and (3) to present resulting national and regional figures of HA bacteremia.

METHODS

Data Sources in HAIBA

We used 2 data sources in this study: the Danish Microbiology Database (MiBa) and the Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR). Data were linked by unique civil registration numbers (CPR numbers). The data extraction was conducted on November 18, 2015.

The MiBa includes microbiological test results from all Danish DCMs.Reference Voldstedlund, Haarh and Molbak 13 We extracted data for all blood cultures with a sampling dates between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2014. Information included sampling date and time, microbiological tests requested, and microorganisms identified.

The DNPR includes administrative information on all inpatient and outpatient contacts with the secondary and tertiary healthcare system.Reference Lynge, Sandegaard and Rebolj 14 This information includes date and time of admission and discharge as well as codes for hospitals and departments. We created an algorithm that related separate contacts to create coherent courses of admission.Reference Gubbels, Nielsen, Sandegaard, Mølbak and Nielsen 15

Algorithm

A case of HA bacteremia was based on at least 1 blood culture positive for a bacterial or fungal pathogen drawn between 48 hours after admission and 48 hours after discharge. Supplementary Table 1 describes the algorithm in detail.Reference Møller, Jensen and Prag 35

Incidence Calculation

Incidence was calculated as incidence density: the number of HA bacteremias per 10,000 risk days. Only the first bacteremia in a course of admission was included because subsequent bacteremia cases are not statistically independent in the same patient.Reference Ostrowsky 16 Risk days were calculated from the number of hours that passed from 48 hours after admission until the sample was acquired for the first positive blood culture or 48 hours after discharge. Each case was attributed to the department where the patient was located at the time of sampling. If a case had a sampling date and time within 48 hours after discharge, the infection was attributed to the discharging department.

Prevalence Calculation

Prevalence was estimated for each day in the period 2010–2014, calculated as the number of hours that patients with a HA bacteremia were in a particular department on a given day divided by the total number of risk days in the same department on that day. The duration of a bacteremia episode was arbitrarily set at 14 days. If a positive blood culture with a pathogen was found within 14 days, a new 14-day window began. Each case was attributed to the department where the patient was admitted on the date for which the prevalence was calculated. In the prevalence calculation, consecutive episodes within a course of admission were also included. A new HA bacteremia case was counted if it occurred after the duration of the previous one. Risk days were counted from >48 hours after admission until discharge.

Trend Analysis

Incidence of HA bacteremia was described by sex and by age at admission. Patients with temporary CPR numbers (eg, travelers) were excluded from age-group analyses because their CPR numbers did not allow for reliable age calculation. This exclusion involved 0.3% of all data. The 10 most frequently occurring microorganisms were identified among HA bacteremia cases. Trends in incidence of HA bacteremia were analyzed using Poisson regression for each region, age group, and sex, with risk days as exposure (ie, the denominator). Annual increase was calculated using monthly time units. We assessed whether it was reasonable to assume a trend. The median daily prevalence and range between daily prevalence estimates were calculated for each region and the entire country, as well as by age group and sex.

Comparison to PPSs

Data from PPSs were collected in autumn 2012 and spring 2013 from Danish hospitals in the Capital Region of Denmark and Region Zealand on a voluntarily basis. In autumn 2012, 66 departments from 10 hospitals participated and in spring 2013, 58 departments from 8 hospitals participated.

Data included CPR numbers of all patients present on the day of the PPS and whether patients had a HA bacteremia. Case definitions used in the Danish PPS were adapted from the 2008 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) case definitions.Reference Horan, Andrus and Dudeck 17 , 18 Apart from bacteremia (confirmed presence of bacteria/fungi in blood), the PPS case definition included patients with symptoms of sepsis and treatment for bacteremia without positive blood cultures (clinical sepsis). Patients were evaluated manually by teams of 2 infection control specialists using medical records and electronic laboratory and medication systems.

Prevalence data from the algorithm were linked to PPS data using CPR number and date of PPS. Sensitivity and specificity were calculated, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated assuming binomial distribution. Discordant cases were evaluated to assess reasons for discrepancies, using notes from the PPS and, when possible, medical records. Information on department specialty was also analyzed, based on PPS data.

Software

Coding was conducted using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Trends in Incidence and Prevalence

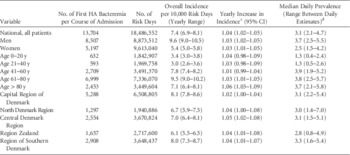

Between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2014, a total of 13,704 first episodes of HA bacteremia per course of admission were identified by the algorithm, with an incidence of 7.4 per 10,000 risk days (range, 6.9–8.1) (Table 1). The incidence among men was higher than among women. Significantly increasing trends in incidence were observed (Figure 1 and Table 1). The number of HA bacteremia cases did not change (data not shown).

FIGURE 1 Incidence per 10,000 risk days of hospital-acquired bacteremia per month in Denmark for all patients and by sex between 2010 and 2014. Data were acquired November 18, 2015.

TABLE 1 Incidence and Prevalence of Hospital-Acquired Bacteremia in Denmark, Stratified by Sex, Age,Footnote a and Region Between 2010 and 2014Footnote b

NOTE. HA, hospital acquired.

a Patients with temporary CPR numbers were excluded from age group analysis, as these CPR numbers do not allow for reliable age calculations.

b Data were acquired on November 18, 2015.

c Trend in incidence estimated using Poisson regression.

d Daily prevalence estimates for January 2010 were excluded because they were unreliable due to the start-up phase of the data.

Incidence increased with age, reaching the highest incidence among patients aged 61–80 years. We observed an increase in incidence over time in all age groups, but the increase was only statistically significant in the 2 oldest age groups. Regional incidence varied between 6.1 and 8.1 per 10,000 risk days and showed an increasing trend. A median daily prevalence of 3.1% (range between daily estimates, 2.1%–4.7%) was estimated, showing minimal regional variation. While incidence of HA bacteremia was highest among 61–80-year-old patients, the prevalence of HA bacteremia was similar among the 3 oldest patient groups. Prevalence, like incidence, was higher among men than women.

Microbiological Findings

Among 13,704 cases of HA bacteremia (including double infections and only first episodes within courses of admission), 277 different microorganisms were identified. The general distribution reflected the older age groups (Table 2). However, younger patients showed some differences. Staphylococcus aureus was most frequent in the 3 youngest age groups. In the age group of 0–20 years, Group B streptococci (GBS) and non-hemolytic streptococci of the S. mitis group were among the 10 most frequently identified microorganisms, and among 21–40-year-old patients, Group A streptococci were among the top 10. The distribution of microorganisms among men and women was similar; the same 10 microorganisms were found in a slightly different order (data not shown).

TABLE 2 Proportion of the 10 Most Frequent PathogensFootnote a Among All Pathogens Identified in Hospital-Acquired Bacteremia Cases and Stratified by Age GroupFootnote b

a Pathogens according to the classification as presented in Supplementary Table 1.

b Patients with temporary CPR numbers were excluded from age group analysis, as these CPR numbers do not allow for reliable age calculations.

Comparison of HAIBA With PPS

PPS data were collected from 2,146 patients. Because of incorrect or missing CPR numbers, 11 patients were excluded. Of the remaining 2,135 patients, 28 were registered on 2 PPS days and 1 was registered on 3 PPS days. Furthermore, when linking PPS data to HAIBA, another 179 records were excluded either because admissions lasted ≤48 hours because patients were recorded in the DNPR as outpatients or because the patient was not recorded at all in the DNPR on the prevalence date. Notably, none of these patients were reported as having HA bacteremia.

Finally, the study included 1,986 records from 1,959 patients: 1,541 records from the Capital Region and 445 from the Region Zealand. Among them, 47 (2.2%) were reported with HA bacteremia, 43 of 1,541 (2.8%) occurred in the Capital Region and 4 of 445 (0.9%) occurred in Region Zealand. Comparison with HAIBA showed that 17 cases were identified in both HAIBA and PPS, 13 were identified only in HAIBA, and 30 were identified only in PPS.

We ascertained 2 main reasons that HAIBA identified HA bacteremia not reported by PPS (Table 3). First, in 6 cases, laboratory results were not known at the time of the PPS, whereas HAIBA was able to count these patients and date their infections retrospectively. Second, 6 patients had HA bacteremia but were not reported in the PPS, probably because they no longer had bacteremia at the time of the PPS. The majority missed by HAIBA (55%) had only negative blood cultures or no samples taken at all; most were admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) or hematology departments. When examining medical records, it was difficult to determine whether these patients had clinical sepsis due to underlying illnesses or were being treated for various other conditions.

TABLE 3 Patient Characteristics, Specialty of Participating Departments and Microbiological Findings of Patients Included in the Comparison of Data From the Danish Hospital-Acquired Infections Database (HAIBA) and Point Prevalence Survey (PPS) Data

NOTE. ICU, intensive care unit.

a As reported by PPSs.

Overall, HAIBA reached a sensitivity of 36.2% (17 of 47; 95% CI, 23.5%–51.0%) and a specificity of 99.3% (1,926 of 1,939; 95% CI, 99.0%–99.7%). When excluding the ICUs and hematology departments, this sensitivity increased to 44.4% (8 of 18; 95% CI, 24.3%–70.2%), and specificity increased to 99.5% (1,743 of 1,751, 95% CI, 99.3%–99.9%).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we describe an algorithm for continuous national monitoring of HA bacteremia in Denmark, using existing data sources (ie, HAIBA), thus avoiding administrative burden and interpersonal differences in classification of infections.

The algorithm used in this study has 3 main components: detection of pathogens, classification of origin and, for prevalence calculations, definition of new episodes.

The determination of whether a microorganism is pathogenic or a likely contaminant is not always straightforward. If contaminants are repeatedly isolated, they may have clinical relevance (eg, as a cause of catheter-associated bacteremia). For the HA bacterimia algorithm, we classified microorganisms as pathogens and contaminants, prioritizing specificity over sensitivity. A few differences were observed in the most frequent microorganisms compared to our blood-culture utilization study. Enterococcus faecium and Candida glabrata were more frequently cultured in samples from HA bacteremia. Both microorganisms are associated with prior or concomitant antimicrobial treatment, and these cases likely reflect an increased burden of illness and increased length of stay. Reassuringly, Streptococcus pneumoniae, which typically causes community-acquired bacteremia (and is ranked fourth among all positive blood cultures), was not found among the top 10 microbial causes of HA bacteremia. GBS bacteremia in the youngest age group may be explained by high incidence among neonates. This pathogen may become more important in older age groups in the future, particularly among patients with diabetes.Reference Ballard, Schønheyder and Knudsen 19 The larger representation of particularly pathogenic microorganisms among younger patients is related to less comorbidity.

The second component of the algorithm involves categorization of bacteremia as HA at the 48-hour cutoff. This cutoff was introduced in the 1970s to standardize surveillance when assessment of medical records and other clinical details was impossible.Reference McGowan, Barnes and Finland 20 More recently, the CDC introduced this cutoff in its PPS methodology. 21 The Danish PPS describes a HAI as one that is neither confirmed nor under incubation upon admission. The incubation period is defined as ≥48 hours unless the patient underwent an invasive procedure. 18 Other electronic surveillance systems are also using a 48-hour cutoff.Reference Leth and Møller 6 , Reference Redder, Leth and Møller 9 , Reference Woeltje, McMullen, Butler, Goris and Doherty 22 – Reference Pokorny, Rovira, Martín-Baranera, Gimeno, Alonso-Tarrés and Vilarasau 24 The number of (positive) blood cultures was shown to decrease soon after admission (day 1) and to increase from day 4 onward.Reference Gubbels, Nielsen and Voldstedlund 12 This finding may also suggest that 48 hours is a useful cutoff.

For prevalence calculations, subsequent infections were included, as is done in PPS, requiring a cutoff for duration of infection, after which new bacteremia cases can be counted. In the future, it may be possible to refine the estimation of duration by including data on antibiotic treatment.

An algorithm eliminates subjectivity of personal judgment, but it may misclassify in some cases. We evaluated how the HA bacteremia algorithm we created for use with HAIBA related to PPS because it is expected to replace the PPS method in Denmark. Our results showed high specificity but low sensitivities of 36% for all departments and 44% when excluding ICUs and hematology departments. However, PPS is not a gold standard, and re-evaluation of medical records showed that, for several patients, it was debatable whether they had bacteremia/clinical sepsis. Therefore, the real sensitivity of the algorithm may well be higher.

The potential underestimation of HA bacteremia in the ICU and among hematological patients may be caused by the exclusion of contaminants that may have clinical relevance in patients with central venous catheters. However, PPSs may have overestimated HA bacteremia in this group. Neutropenic and leukopenic fever are difficult to distinguish from bacteremia. Patients are, by protocol, given antibiotics as a precaution for developing bacteremia, making it difficult to culture microorganisms. Finally, many ICU patients have (multiple) organ failure, which can be mistaken for bacteremia/clinical sepsis. Although it is challenging to identify HA bacteremia in these patients with an algorithm, it may be useful to investigate the possibility of including antibiotic treatment and/or chemotherapy visits. However, such additions may introduce false positives, which might make HAIBA less acceptable for hospitals.

The increasing trend in national incidence of HA bacteremia seen in HAIBA is in line with a European study.Reference de Kraker, Jarlier, Monen, Heuer, van de Sande and Grundmann 25 However, in contrast to the European study, the number of HA bacteremia cases did not increase, and the trend seems driven by a decreasing denominator (ie, risk days). Length of stay decreased in Denmark over the studied period.Reference Gubbels, Schultz Nielsen, Sandegaard, Mølbak and Nielsen 26 However, with shorter admissions we would also expect a decrease in the number of HA bacteremia cases. The fact that this was not seen could have been related to an aging population and more advanced treatment given at older age. Incidence did increase over time among the oldest age groups, while it remained stable for other age groups.

Although the number of cases identified by HAIBA was lower than by PPS, the estimated prevalence was higher; HAIBA estimated a median prevalence of 3.1% (range between daily estimates 2.1%–4.7%) between 2010 and 2014 versus 1.1% (range, 1.1%–1.6%) by PPS over the same period. 3 This finding can be explained by several factors, including the fact that HAIBA excludes admissions ≤48 hours from the denominator and differences in underlying concepts and methods.

Incidence of HA bacteremia varied between regions and hospitals, possibly due to differences in patient population in terms of case mix and complexity of treatment. A marked difference was also seen in incidence and prevalence between men and women. Other studies have also reported this difference.Reference Uslan, Crane and Steckelberg 27 – Reference Moon, Ko, Park, Hur and Yun 29 Several studies have reported that men were more likely to develop bacteremia secondary to urinary catheter–associated bacteriuria than women.Reference Krieger, Kaiser and Wenzel 30 – Reference Greene, Chang and Kuhn 32 However, the indication for catheterization (eg, obstruction) could be a confounder in these studies.Reference Conway, Carter and Larson 33 In line with this finding, we observed that Escherichia coli was the most common pathogen among patients >60 years of age.

Further investigation of patient populations is particularly important when data are to be used for interfacility comparisons, requiring adjustment for confounders.Reference Harris and McGregor 34

The strength of HAIBA lies in comparing hospitals and departments with themselves over time. By doing so, it can support prioritization in infection control and can serve as a tool to evaluate interventions and for audits. Hospitals will receive data on individual patients with HA bacteremia to further investigate signals and trends. When HAIBA has been actively used for a substantial period its effect on in incidence, morbidity and mortality should be evaluated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the members of the HAIBA Advisory Forum, Kim Gradel (Center for Clinical Epidemiology, South, Odense University Hospital and Research Unit of Clinical Epidemiology, Institute of Clinical Research, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark) and Christina Vandenbroucke-Grauls (Department of Medical Microbiology and Infection Control, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) for their feedback regarding the algorithm. We thank Kenn Schultz Nielsen (Department of IT-Projects and Development, Danish Health Data Authority) for his involvement in the development of HAIBA. We also thank Christian Stab Jensen (Department of Microbiology and Infection Control, SSI) and all of the infection control nurses and medical doctors who collected data for the PPS. We also thank Manon Chaine (Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, SSI) for her assistance in data entry of the PPS data.

The Danish Data Protection Authority approved this study as part of the development of HAIBA (registration no. 2015-54-0942).

Financial support: This work was funded by the Danish Ministry of Health and the Elderly as part of the development of HAIBA.

Potential conflicts of interest: All authors report no conflict of interest relevant to this article.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2017.1