Central venous catheters (CVCs) facilitate diagnostic, monitoring, and therapeutic activities in contemporary clinical care. Recently, peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) have emerged as the most common type of CVC in the hospital setting.Reference Chopra, Anand, Krein, Chenoweth and Saint 1 , Reference Climo, Diekema and Warren 2 First developed in 1975,Reference Hoshal 3 PICCs are associated with fewer insertion risks (eg, injury to the vessels of the neck and chest) than CVCs, and they are commonly placed by vascular access nurses at the bedside.Reference Chopra, Kuhn and Ratz 4 – Reference Alexandrou, Spencer, Frost, Mifflin, Davidson and Hillman 7 Consequently, PICCs are not only technically easier to place but also are more convenient and accessible for clinicians than traditional CVCs.Reference Lamperti, Bodenham and Pittiruti 8 For these reasons, their use in the general wards, intensive care units (ICUs), and outpatient settings has grown substantially.Reference Ajenjo, Morley and Russo 9 , Reference Aw, Carrier, Koczerginski, McDiarmid and Tay 10

However, PICCs are not without inherent risks. For example, a recent study reported that 1 of every 3 PICCs placed in an inpatient or outpatient setting is associated with an adverse event.Reference Grau, Clarivet, Lotthe, Bommart and Parer 11 The development of central-line–associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) is a complication associated with PICC use.Reference Warren, Quadir, Hollenbeak, Elward, Cox and Fraser 12 , Reference Singh, Kumar, Sundaram, Kanjilal and Nair 13 In a study of hospitalized patients with PICCs, rates of PICC-CLABSI were statistically similar to those of conventional CVCs.Reference Safdar and Maki 14 Similarly, another cohort study found that PICCs were associated with a CLABSI rate of 3.13 per 1,000 catheter days in hospitalized patients, a rate exceeding that of CVCs.Reference Pongruangporn, Ajenjo and Russo 15 Because PICCs are often used for transitions of care, this risk is not restricted to the acute-care setting. A recent prospective study of nursing home residents found that CLABSI complicated the course of 4% of PICCs used in this setting.Reference Chopra, Montoya and Joshi 16 Similarly, a recent study of outpatients with PICCs reported that confirmed or suspected infection was a common cause for PICC removal.Reference Cornillon, Martignoles and Tavernier-Tardy 17

One potential strategy to prevent CLABSI is to avoid the use of PICCs in patients at high risk for CLABSI. For example, studies have shown that immunosuppression, multilumen PICCs, length of hospital stay, and PICC placement in an ICU setting are associated with greater risk of CLABSI.Reference Chopra, Govindan and Kuhn 18 , Reference Baxi, Shuman and Scipione 19 However, how best to operationalize or prioritize these factors when making decisions regarding PICC use is not clear. To date, no risk model has been developed to estimate an individual’s risk of PICC-CLABSI prior to device placement. To bridge this gap, we used data from an ongoing prospective cohort study to develop the Michigan PICC-CLABSI (MPC) score to predict CLABSI in patients with PICCs.

METHODS

Study Setting and Participants

The study was conducted using data from the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety (HMS) consortium, a 48-hospital collaborative quality initiative supported by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and Blue Care Network. The design and setting of this consortium have been previously described.Reference Greene, Spyropoulos and Chopra 20 – Reference Grant, Greene, Chopra, Bernstein, Hofer and Flanders 22 In brief, HMS hospitals prospectively collect data regarding PICC use and outcomes in hospitalized medical patients using a protocoled sampling strategy at participating hospitals.Reference Greene, Spyropoulos and Chopra 20 Adult medical patients admitted to a general ward or ICU of a participating hospital who receive a PICC for any reason during clinical care are eligible for inclusion. Patients who are (1) under the age of 18, (2) pregnant, (3) admitted to a nonmedical service (eg, general surgery), or (4) admitted under observation status are excluded.

At each hospital, dedicated, trained, medical-record abstractors use a standardized template to collect clinical data directly from health records of patients. Patients with PICCs are sampled on a 14-day cycle, and data from the first 17 cases that meet eligibility criteria within each cycle are collected and stored within a patient registry. To ensure adequate representation of critically ill patients, 7 of the 17 cases include PICC placement in an ICU setting. All patients are followed until PICC removal, death, or 70 days, whichever occurs first. Data collection for the HMS project is ongoing; for this analysis, complete data from patients enrolled in the study between January 2013 and October 2016 were included.

Covariables and Definitions

Detailed medical history including comorbidities, physical findings, laboratory data, and medication data are collected from the medical record at the time of hospital admission. The following data are abstracted directly from the medical records: age (≤64 vs ≥65 years) sex; race; body mass index; tobacco use (never, former, or current); admitting diagnosis; prior CLABSI within 3 months of PICC placement; parenteral nutrition via PICC; receipt of hemodialysis; chemotherapy or blood administration during hospitalization; presence of active infection and site of infection; past or present hematological malignancy; active cancer (defined as receipt of chemotherapy while PICC was in place); existing central venous catheter when PICC was placed (yes/no); diabetes mellitus (uncomplicated vs complicated by micro- or macrovascular complications); history of cerebrovascular accident or transient ischemic attack; history of myocardial infarction; venous thromboembolism prophylaxis (ie, receipt of subcutaneous heparin twice or thrice daily regimens or use of enoxaparin at prophylactic doses or treatment dose anticoagulation for any reason); aspirin; statin; erythropoiesis stimulating agents; and antibiotic administration. Laboratory data including white blood cell count, hemoglobin, platelet count and international normalized ratio at the time of PICC placement are also collected.

PICCs are vascular access devices inserted into the veins of the upper extremity that terminate at the cavoatrial junction; thus, midlines, conventional CVCs, or catheters placed in lower extremity veins are excluded. However, the presence of a CVC in a limb or neck at the time of PICC insertion is captured in the data collection. Data regarding PICC characteristics (eg, gauge, lumens, tip position verification) and indication for PICC placement are obtained directly from vascular nursing or interventional radiology insertion notes or the order for PICC placement. PICC-CLABSI was defined using a modified version of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Healthcare Safety Network (CDC/NHSN) definition.Reference Greene, Flanders, Woller, Bernstein and Chopra 21 The definition was modified as follows: (1) cases for which CLABSI was documented in the medical record by medical providers based on clinical data (eg, cultures) regardless of conformation to the NSHN definition were included; (2) recording of symptoms of CLABSI (eg, fever, hypotension or rigors) was restricted to 3 days before or after the date of a positive blood culture; (3) determination of infection at another site was generalized to the entire PICC dwell time. Thus, if a patient had an infection at another site at any time the PICC was in place, we did not count these cases as CLABSIs. Changes to the definition were necessary because (1) hospital abstractors are not trained infection control preventionists and therefore cannot reliably adjudicate infection at another site; (2) abstractors had limited time assigned to the project and consideration of abstractor burden necessitated limiting data review; and (3) every hospital has a unique practice for blood culture collection, line removal, and reporting, which can only be addressed through a more “operational” study definition. However, we believe the modifications to increase the specificity for CLABSI increase the likelihood that more “true positive” cases are included with our approach.

Ascertainment of Outcomes

The primary outcome was CLABSI defined using modified CDC/NHSN criteria in a patient with a PICC. Additionally, microbiologically confirmed catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI) with a positive catheter tip culture in the setting of suspected PICC infection was evaluated as a secondary analysis.Reference Mimoz, Lucet and Kerforne 23 Patients in whom CLABSI was suspected but microbiologic findings were not available (eg, PICC removed without confirmatory blood cultures) were excluded.

Statistical Analyses

Putative risk factors associated with CLABSI were assessed according to a previously published and validated conceptual framework for PICC complications.Reference Chopra, Anand, Krein, Chenoweth and Saint 1 In accordance with this framework, covariates associated with CLABSI were summarized as patient, provider, and device factors using descriptive variables. Missing data were assumed to be missing at random, with missing values imputed through a 10-fold multiple imputation procedure.Reference Hopke, Liu and Rubin 24 , Reference Rubin and Schenker 25 Of all the variables included, only 15 had missing data with an average of 6.4% missing data per missing variable. Patients were censored for CLABSI at the time of PICC removal or at 70 days if the PICC was still in place and no laboratory evidence to suggest CLABSI (ie, positive blood or tip cultures) was present. Unadjusted associations of covariables with time to CLABSI were initially assessed with results expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

The MPC score was developed in accordance with published and validated risk assessment tools.Reference Fine, Auble and Yealy 26 , Reference Halbesma, Jansen and Heymans 27 Point values were assigned to create a tool with an easily applied 0 to 3 integer point system, with individual points reflecting the relative magnitude of the regression coefficients in the model. Validation of the final model was performed using methodologic standards for prediction rules.Reference Wasson, Sox, Neff and Goldman 28 , Reference Heagerty and Zheng 29 Baseline covariates with an unadjusted P value ≤.10 in Cox proportional hazards models (with robust sandwich standard error estimates to account for hospital-level clustering) were considered candidate predictors. In keeping with recommended approaches,Reference Moons, Kengne and Woodward 30 predictors were entered into the multivariable model, with the final model fit by stepwise selection. The proportional hazards assumption was verified, and no covariates violated this assumption. Using coefficients derived from the multivariable model, integer point values were assigned to each covariable so that a total point score for CLABSI risk could be estimated for each patient.

The predictive performance of the MPC score was assessed using time-dependent AUC values and predicted CLABSI rates at clinically relevant time points over a range of 6 to 40 device days.Reference Heagerty, Lumley and Pepe 31 A bootstrap internal validation procedure with 200 bootstrap resamples was performed to determine the optimization of discrimination.Reference Miller, Langefeld, Tierney, Hui and McDonald 32 , Reference Harrell 33 The predictive performance of the model using the original model coefficients and the assigned integer point values was compared to confirm that there was no loss in predictive ability of the model using the integer point system. Significant findings were first reported based on a type I error rate of 0.05 per test, with no correction for multiple testing. To control for false discoveries due to multiple testing, a Bonferroni correction was next used requiring a P-value threshold of .005 for covariables to remain in the final model.Reference Shaffer 34 All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R version 3.2.4 software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Ethical and Regulatory Oversight

The University of Michigan Medical School’s Institutional Review Board reviewed this study and assigned it a “not regulated” status.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics and Outcomes

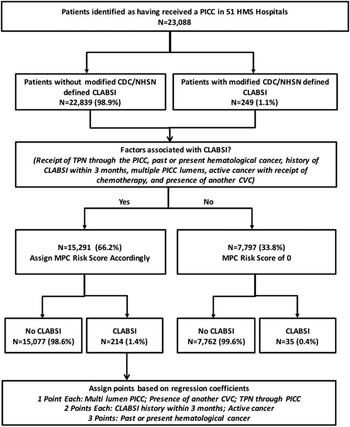

Over the study period, a total of 23,088 patients received PICCs and were included in this analysis. Within this cohort, a total of 249 (1.1%) patients developed CLABSI according to the modified CDC/NHSN criteria (Figure 1). Patients that developed PICC-CLABSI more often were on hemodialysis (8.0% vs 3.4%; P<.01), were receiving chemotherapy (16.9% vs 2.5%; P<.01), and had past or present hematological malignancy (20.1% vs 2.9%; P<.01) than patients that did not develop this event. Similarly, patients with PICC-CLABSI were also significantly more likely to have experienced an episode of laboratory-confirmed CLABSI in the 3 months prior to PICC insertion (8.8% vs 1.1%; P<.01). Importantly, patients that developed CLABSI also more frequently had another CVC in situ at the time the PICC was placed—often in an ICU setting (29.3% vs 14.1%; P<.01) (Table 1).

FIGURE 1 Study Flow Diagram

TABLE 1 Descriptive Characteristics of Patients With and Without Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Central-Line–Associated Bloodstream Infection (PICC-CLABSI)

NOTE. IQR, interquartile range; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome; CLABSI, central line-associated bloodstream infection; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism; VTE, venous thromboembolism; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; TIA, transient ischemic attack; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LOS, length of stay; CVC, central venous catheter; PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter; TPN, total parenteral nutrition; ICU, intensive care unit.

a At time of PICC placement.

b Within the previous 30 d.

c Diabetes without complications=diabetes without documented retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, cardio- or cerebrovascular events.

With respect to provider characteristics, no significant differences in the risk of CLABSI between PICCs placed by vascular access nurses versus interventional radiologists were observed. Similarly, no differences in the number of insertion attempts, arm or vein used for insertion, hospital location for insertion (ie, ICU, general floor, outpatient, or the emergency room) were noted. However, patients that received a PICC to deliver chemotherapy or total parenteral nutrition were more likely to develop a CLABSI than those who received PICCs for intravenous antibiotic therapy (13.3% vs 2.4%, and 10.0% vs 5.1%, respectively; P<.01 for both, respectively). Similarly, longer dwell time (median 15 vs median 11 days; P<.01) and multilumen versus single-lumen devices (78.3% vs 62.6%; P<.01) were more frequently associated with CLABSI.

Patient, Provider, and Device Predictors of PICC-CLABSI

Associations between patient, provider, and device characteristics and PICC-CLABSI are shown in Table 2. Several patient factors such as hemodialysis (hazard ratio [HR], 2.51 [95% CI, 1.38–4.58]), receipt of TPN (HR, 2.14 [95% CI, 1.61–2.85]), and active cancer (HR, 6.37 [95% CI, 4.28–9.48]) were associated with PICC-CLABSI. Additionally, history of CLABSI within 3 months of PICC insertion (HR, 5.71 [95% CI, 3.67–8.87]) and presence of an existing CVC at time of PICC placement (HR, 2.54 [95% CI, 1.76–3.66]) were both associated with risk of infection. As the number of PICC lumens increased, the risk of subsequent CLABSI also increased (HR, 1.73 [95% CI, 1.37–2.17] and HR, 3.18 [95% CI, 2.20–4.59], for double- and triple-lumen vs single-lumen PICCs, respectively).

TABLE 2 Unadjusted Associations Between Patient, Provider, and Device Factors and Risk of Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Central-Line–Associated Bloodstream Infection (PICC-CLABSI)

NOTE. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome; CLABSI, central line-associated bloodstream infection; DVT, deep-vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism; VTE, venous thromboembolism; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; TIA, transient ischemic attack; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LOS, length of stay; CVC, central venous catheter; PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter; TPN, total parenteral nutrition; ICU, intensive care unit.

Multivariable Models and Risk Scoring System

Six factors emerged as being significantly associated with CLABSI on multivariable models: receipt of TPN through the PICC, past or present history of hematological cancer, history of CLABSI within 3 months, number of PICC lumens, active cancer with ongoing chemotherapy, and presence of another CVC at the time of PICC placement. To create the MPC score, we assigned points to each of these 6 factors based on their regression coefficients (Table 3). Of the 23,088 patients, 7,797 (33.8%) had none of these risk factors and were therefore assigned 0 points. The overall rate of CLABSI during the follow-up period in this group was 0.4% (n=35). In the remaining 66.2% of patients with 1 or more factors (n=15,291), a 3-fold increase in the frequency of CLABSI was observed (1.4%; n=214). Observed CLABSI rates during the follow-up period were 0.7%, 1.7%, 2.7%, 4.4%, and 10.8% for patients with scores of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively.

TABLE 3 Michigan PICC-CLABSI (MPC) Risk Score for Infection

NOTE. PICC-CLABSI, peripherally inserted central catheter central-line–associated bloodstream infection; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter; CVC, central venous catheter.

a Points assigned to each predictor based on size of regression (ß) coefficient from the multivariable model.

In a Cox-proportional hazards model with risk score as a continuous predictor, MPC score was significantly associated with CLABSI (P<.0001). For every point increase in MPC score, the HR of CLABSI increased by 1.63 (95% CI, 1.56–1.71). The most powerful predictors of CLABSI were hematological cancer (3 points) or prior CLABSI within 3 months of PICC placement (2 points). The predicted probability of CLABSI for PICC dwell times of 6 to 40 days ranged from 0.2% to 1.1% for patients with a risk score of 0, to 2.0% to 11.8% for patients with a risk score of 5 (Table 4). The areas under the time-dependent receiver-operating-characteristics curves ranged from 0.70 (95% CI, 0.64–0.76) to 0.80 (95% CI, 0.76–0.84) for PICC dwell times of 6 to 40 days, with the maximum AUC value occurring at 21 days indicating good model performance (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2 Receiver-operating curve for CLABSI Risk Model (stratified by dwell time)

TABLE 4 Frequency and Rate of PICC CLABSI by MPC Risk Score

NOTE. PICC-CLABSI, peripherally inserted central catheter central-line–associated bloodstream infection; MPC, Michigan PICC-CLABSI; VTE, venous thromboembolism; CI, confidence interval; CVC, central venous catheter.

Optimized adjusted AUC values for the MPC score calculated using bootstrapped samples ranged from 0.67 to 0.77 for PICC dwell times of 6 to 40 days, with the maximum AUC value occurring at 21 days, indicating good model calibration. The performance of the MPC score was further assessed with events restricted to those meeting CRBSI definitions (n=184 of 249 cases). Using this more restrictive approach, the predictive performance of the model was comparable to outcomes using the modified NHSN CLABSI definition, with AUC values ranging from 0.69 to 0.80 for PICC dwell times of 6 to 40 days.

DISCUSSION

In this study of 23,088 patients, we derived a PICC-CLABSI risk-prediction tool—the MPC score—for PICC-CLABSI. Using clinically granular data derived directly from medical records of patients that developed CLABSIs, we identified 6 factors that were most often associated with this adverse event. By assigning points to the regression coefficients of each of these factors, we developed and internally validated a quantitative method of estimating the probability of developing CLABSI through a PICC. Because this score can be calculated before device insertion, we believe it has the potential to inform use of PICCs and improve patient safety in important and novel ways.

Although PICCs are associated with many advantages, mounting evidence also suggests that they are associated with important complications, including CLABSI and thromboembolism. For example, a recent systematic review of 23 studies that included more than 50,000 patients reported that rates of PICC-CLABSI were statistically identical to CLABSI from other CVCs in the inpatient setting.Reference Chopra, O’Horo, Rogers, Maki and Safdar 35 In another study, Ajenjo et alReference Ajenjo, Morley and Russo 9 reported the rate of PICC-associated bloodstream infection to be 3.13 per 1,000 catheter days, with higher rates in ICU than non-ICU areas. Despite this knowledge, risk factors that contribute specifically to PICC-CLABSI in individual patients have not been well studied. Available prediction models are derived from single-center studies that feature homogenous populations, limiting their applicability.Reference Ajenjo, Morley and Russo 9 , Reference Pongruangporn, Ajenjo and Russo 15 , Reference Chopra, Govindan and Kuhn 18 The MPC score is a departure from the status quo because it addresses many of these issues and allows for quantitative estimation of PICC-CLABSI in new ways.

Some predictors of PICC-CLABSI identified in our model reflect those reported in other studies. For example, we and others have shown that the number of device lumens is strongly associated with PICC-CLABSI.Reference Chopra, Anand, Krein, Chenoweth and Saint 1 , Reference Pongruangporn, Ajenjo and Russo 15 , Reference Baxi, Shuman and Scipione 19 , Reference Chopra, O’Horo, Rogers, Maki and Safdar 35 Efforts to place PICCs with the fewest lumens have therefore been developed and appear effective in reducing complications.Reference O’Brien, Paquet, Lindsay and Valenti 36 – Reference Smith, Moureau and Vaughn 38 Similarly, administration of TPN via PICCs is known to be significantly associated with CLABSI.Reference Wylie, Graham and Potter-Bynoe 39 Prevention efforts tailored toward TPN such as care bundles that dedicate 1 lumen for TPN or change of TPN infusion sets every 24 hours are valuable in patients with PICCs.Reference Hakko, Guvenc, Karaman, Cakmak, Erdem and Cakmakci 40 , Reference Harnage 41 The use of alternative vascular access devices such as ports or tunneled catheters (for which rates of infection are known to be lower than those for PICCs) may be more effective in preventing CLABSI. The Michigan Appropriateness Guide to Intravenous Catheters (or MAGIC) offers an algorithmic approach to selecting devices other than PICCs in such situations.Reference Chopra, Flanders and Saint 42

If patients have a high MPC score, what may be done to avert CLABSI? Several strategies are feasible. First, reevaluating the necessity of a PICC is prudent. As illustrated in a study of more than 3,000 patients in 10 Michigan hospitals, a large proportion of PICCs might be avoidable.Reference Greene, Spyropoulos and Chopra 20 Similarly, when comparing oral versus intravenous antibiotic treatment via a PICC, outcomes might not be dissimilar despite greater risk of PICC-related complications.Reference Keren, Shah and Srivastava 43 , Reference Shah, Srivastava and Wu 44 Thus, policies that direct high-risk patients to receive early infectious diseases consultation to determine appropriateness versus alternative forms of antibiotic therapy (eg, oral therapy, shorter duration, etc.) might be effective.Reference Shrestha, Bhaskaran, Scalera, Schmitt, Rehm and Gordon 45 , Reference Sharma, Loomis and Brown 46 Second, patients with scores above a preset threshold might be subject to stricter clinical vigilance, such as limited device access or device care by a single, high-functioning team within models such as “catheter rounds.” Third, a higher risk score may prompt consideration of an antimicrobial-impregnated or -coated PICC, as these have been shown to reduce risk of CLABSI in patients at high risk of this event.Reference Kramer, Rogers, Conte, Mann, Saint and Chopra 47

Our study has several limitations. First, it was derived and validated within a cohort of hospitalized medical adults; external validation in other patient populations such as pediatric or surgical settings is necessary before widespread use can be recommended. Second, we used a modified CDC/NHSN definition of CLABSI, a change that was necessary to limit abstractor data collection burden and to ensure that the detection of CLABSI was applied similarly across all hospitals by individuals not necessarily trained for this purpose. However, the definition we used is more specific to CLABSI for the following reasons: (1) In an era of payment reform, healthcare providers may not document CLABSI unless they are clinically treating for the same or are fairly certain about the diagnosis. (2) The definition is equally applicable to all sites and thus more internally valid regardless of documentation, blood culture practices, laboratory reporting, etc. (3) The predictive performance of our model was similar when restricted to the more inclusive CRBSI definition, suggesting that our inclusion of CLABSI cases was representative of those with true infection. Third, data used to develop this tool were collected through review of medical records and, as such, are susceptible to reporting bias. However, because the data were sourced directly from medical records by trained abstractors, we believe that this risk was minimized to the extent possible.

Our study also has important strengths. First, we created a model that allows for calculation of a patient-specific CLABSI risk score. Because PICC use continues to rise and comprehensive models to predict risk of CLABSI do not exist, the MPC score offers an important scientific contribution to the literature. Second, the MPC score can help inform not only decisions regarding when a PICC might be the optimal choice but also institutional policies related to surveillance and management of high-risk cohorts. Because both ICU and non-ICU patients are included in the model, it will meet the needs of multiple stakeholders and providers in this regard. Third, the MPC risk score can be provided to clinicians in new and convenient ways, such as handheld applications and smartphone tools. Exploring avenues such as these to bring research to the bedside is a key strength of this scoring method.

In conclusion, we derived and validated a tool that predicts the risk of PICC-CLABSI in a large cohort of hospitalized patients. Future studies that focus on both validating the tool and exploring strategies for implementation in clinical settings are needed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Michigan and Blue Care Network supported data collection at each participating site and funded the data coordinating center but had no role in study concept, interpretation of findings, or in the preparation, final approval or decision to submit the manuscript.

Financial support: Support for Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety Consortium (HMS) is provided by Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Michigan and Blue Care Network as part of the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBSM) Value Partnerships program. Although Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and HMS work collaboratively, the opinions, beliefs and viewpoints expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the opinions, beliefs and viewpoints of BCBSM or any of its employees. Dr Chopra is supported by an AHRQ career development award (grant no. 1-K08HS022835-01).

Potential conflicts of interest: Dr Chopra has received grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the CDC, and the National Institute of Health as well as honoraria for talks as visiting professor. Dr Flanders has received royalties from Wiley Publishing; honoraria for various talks at hospitals as a visiting professor; grants from the CDC, the AHRQ, and BCBSM; and fees for expert witness testimony. Dr Washer has received grant funding from the National Institute of Health, the Healthcare Research Education Trust, and the AHRQ. Drs Herc, Conlon, and Patel report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.