Nosocomial infections are the undesirable result of treatment in a hospital, or a healthcare service unit, not related to a patient’s original condition.Reference Haidegger, Nagy, Lehotsky and Szilágyi 1 Hand hygiene is the primary preventive measure aimed at reducing healthcare-associated infection (HAI) and the emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria. 2 , Reference Pittet, Hugonnet and Harbarth 3 Hand rubbing with alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR) is the most effective method in terms of hand hygiene efficiency.Reference Dicko-Traore, Gire and Brevaut Malaty 4 , Reference Girard, Amazian and Fabry 5 Bactericidal, fungicidal, and viridical properties are directly affected by compliance with hand hygiene steps and duration.Reference Edmonds-Wilson, Campbell and Fox 6 , Reference Gould, Moralejo and Drey 7 The French Hospital Hygiene Society has defined a hand hygiene procedure 8 based on recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO). 2 The duration of the entire procedure is 20–30 seconds and includes 7 steps and drying time (Appendix 1). The introduction of protocols reduces infections.Reference Ng, Wong and Lyon 9 The WHO has listed some factors explaining poor adherence or low compliance to hand hygiene 10 in an emergency department (ED)Reference Pittet, Simon and Hugonnet 11 : overcrowding,Reference Pittet, Hugonnet and Harbarth 3 , Reference Kuzu, Ozer and Aydemir 12 high number of opportunities for hand hygiene per hour of patient care,Reference Pan, Mondello and Posfay-Barbe 13 – Reference Pittet, Stephan and Hugonnet 15 and insufficient time.Reference Dedrick, Sinkowitz-Cochran and Cunningham 16 , Reference Suchitra and Lakshmi Devi 17 Conversely, participation in a hand hygiene campaign and previous training improved adherence to hand hygiene practice.Reference Sax, Uçkay and Richet 18 Among the articles reviewed by the WHO, only 1 study analyzed hand hygiene procedures in an ED. 10 , Reference Pittet, Simon and Hugonnet 11 Moreover, management of life-threatening situations may or may not provide sufficient time required for efficient hand hygiene. This might also be the case when caregivers are confronted with a high patient load. We hypothesized that simulation-based training would improve the duration and quality of hand hygiene. In the present study, we analyzed hand hygiene practices in a pediatric ED and studied the impact of simulations on improving performance. The aim of this study was to assess the quality of hand hygiene with ABHR in different personnel categories before and after simulation-based training (SBT).

Methods

Study design and setting

This prospective study took place in the Pediatric Emergency Department of the University Hospital of Poitiers from November 1, 2017, to March 31, 2018. This 15-bed unit with 25,000 annual admissions employed 13 nurses, 5 nursing assistants, 6 pediatric emergency physicians, and 8 residents. This project was approved by the local ethics committee and was assigned file number 2016-5 by the Hygiene Committee of the University Hospital of Poitiers. All participants signed an informed consent form. Results were kept anonymous.

Objectives

The primary study objective was to assess the duration of hand rubbing before and after a simulation-based training course. We also analyzed the evolution of the duration of hand rubbing over time as the procedure was repeated. The secondary study objectives were (1) to count the number of steps carried out; (2) to analyze the quality of hand hygiene; and (3) to note the presence of jewelry (eg, ring, bracelet, watch), long and/or false fingernails, and/or skin wounds.

Population

All residents, nurses, and nursing assistants who worked in the ED during the study period were recruited. Exclusion criteria were refusal to sign the consent and inability to use ABHR due to an allergy or wound.

Intervention

First, hand hygiene practices were assessed in the pediatric ED during clinical care (assessment A). Hand hygiene was then assessed 45 days later, also during clinical care (assessment B). The assessment observer was present during work days to follow participants during their work shift in the unit. The assessment was not performed in patient rooms but before entering and after exiting them, so the observer would not interfere in the management of the patient. The assessment of each participant was based on recording scores for 10 hand-rubbing procedures during a work day. The most widely used assessment and training method for hand-rubbing technique is based on ultraviolet (UV)-dyed ABHR, which monitors the distribution of a fluorescent marker under UV light.Reference Lehotsky, Szilágyi and Bánsághi 19 , Reference Vanyolos, Peto and Viszlai 20 A fluorescent component (Aniosgel 85 NPC with Tinopal CBS-CL) emits blue fluorescence under UV-A radiation in an educational black box.Reference Garnier, Burger and Salles 21 Blue fluorescence on the hands attested to efficient application of ABHR and disinfection of the corresponding zone; the color black signified an uncleaned area.Reference Girou, Loyeau and Legrand 22 , Reference Laustsen, Lund and Bibby 23

Before assessment A, an annual hand hygiene presentation by the hygiene department along with a monthly reminder of the WHO recommendations was presented during the morning ED staff meeting. Thereafter, caregivers were expected to know these recommendations. Between the A and B assessments, a training video was viewed by the hospital hygiene team, followed by SBT. Each participant performed a series of hand-rubbing procedures with fluorescent ABHR until an optimal quality of hand hygiene was achieved (ie, no dark areas present when hands were tested under the UV light in the black box). Self-assessment of the course was performed by each participant, combined with a questionnaire on professional status, dominant hand, level of experience, and previous experience in a surgical unit.

Participants’ theoretical knowledge and quality of hand hygiene were compared before and after the course.

Outcomes

A timer was used to assess hand-rubbing duration, and hand rubbing was videotaped to count the number of steps followed by the study participant. A score for quality of hand hygiene was calculated from an anatomically based assessment scale for hand hygiene with ABHR that we previously developed and validated.Reference Ghazali, Thomas and Deilhes 24 Scoring was performed by 2 independent observers (observer 1 and 2) from the Simulation Center of the University of Poitiers who were trained to assess hand hygiene technique during simulations. This scale is based on a binary score: 0, not cleaned; 1, cleaned zone. Observers analyzed 22 areas on the dorsal side and 18 areas on the palmar side of each hand (Appendix 2). Theoretical knowledge was assessed by a pretest and a posttest immediately before and after the theoretical course (Appendix 3).

Statistical analyses

Analyses were conducted using Statview version 4.5 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Descriptive analyses used mean and standard deviation (SD) or percentage and confidence interval (CI). Variations between the first and the tenth hand-rubbing procedure of each participant were evaluated by analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures. Comparisons of quantitative variables between the first evaluation and the second evaluation after the course applied the Student t test or the Wilcoxon paired test. Comparisons of qualitative variables applied the χ2 test or the Fisher exact test. Correlation with professional status, dominant hand, level of experience, and previous experience in a surgical unit used linear regression analysis. A P value <.05 was considered significant.

Results

Characteristics of participants

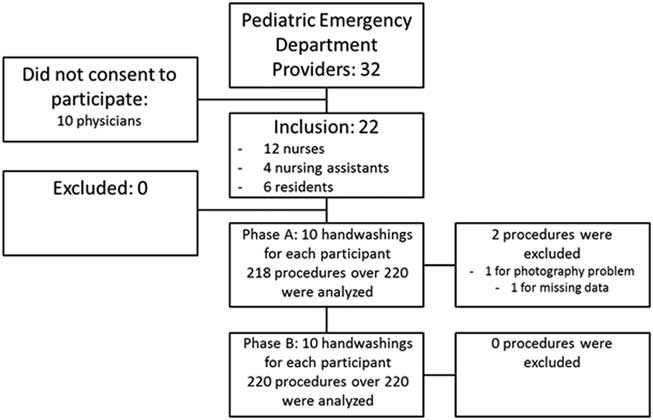

In total, 22 participants were recruited from the 32 pediatric emergency department staff members. No one was excluded; all participated in assessments A and B. Although 2 of the participants performed only 9 hand-rubbing procedures during assessment A, the others performed 10 hand-rubbing procedures. Therefore, we analyzed 218 hand-rubbing procedures during assessment A and 220 hand-rubbing procedures during assessment B. A flow chart is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Flow chart.

The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. Overall, 4 nurses and 1 nursing assistant had worked >1 year in a surgical unit before joining the pediatric emergency department.

Table 1 Demographics of Participants (n=22)

Note. CI, confidence interval.

Primary outcome

The duration of hand rubbing increased between assessment A and assessment B from 31.2 ± 13.6 seconds to 35.8 ± 16.6 seconds (P=.04). During assessment A, the first hand-rubbing procedure was 25.3 seconds long (95% CI, 0.1–22.6), compared to 22.7 seconds (95% CI, 1.2–30.4) for the tenth procedure (P=.07). After simulation training, during assessment B, the first hand-rubbing procedure was 49.6 seconds long (95% CI, 0.1–22.6) which was significantly higher than during assessment A (P<.001). However, the duration significantly decreased from the first to the last procedure to 27.4 seconds (95% CI, 2.9–34.9; P<.001). The duration of the last hand-rubbing procedure was also significantly longer during assessment B than assessment A (P=.003). No differences between nurses, nurse assistants, and residents were detected when procedures were repeated (F=0.372; P=.95).

Secondary outcomes

The numbers of steps performed were 6.03±0.73 during assessment A and 6.33 ± 0.92 during assessment B (P=.13). There was no difference in the minimum number of steps, respectively: 5.18 ± 1.63 steps for assessment A and 5.09 ± 1.65 steps for assessment B (P=.79). Likewise, there was no difference for the maximum number of steps, respectively: 6.95 ± 0.52 steps for assessment A and 6.73 ± 0.75 steps for assessment B (P=.06). Focusing in detail on the 7 steps recommended by the WHO, we detected no difference between the 2 assessments in the average number of missing steps during the 10 hand hygiene procedures (Table 2).

Table 2 Number of Missing StepsFootnote a (N±SD) Among the 10 Hand Hygiene Procedures Performed by 22 Healthcare Providers Before and After Simulation-Based Training

Note. Assessment A: evaluation before SBT, over 10 hand-rubbing procedures; assessment B: evaluation after simulation-based training, over 10 hand-rubbing procedures.

a The 7 recommended steps of WHO: (1) Apply a palmful of the product in a cupped hand, covering all surfaces; (2) Rub hands palm to palm; (3) Right palm over left dorsum with interlaced fingers and vice versa; (4) Palm to palm with fingers interlaced; (5) Backs of fingers to opposing palms with fingers interlocked; (6) Rotational rubbing of left thumb clasped in right palm and vice versa; (7) Rotational rubbing, backwards and forwards with clasped fingers of right hand in left palm and vice versa.

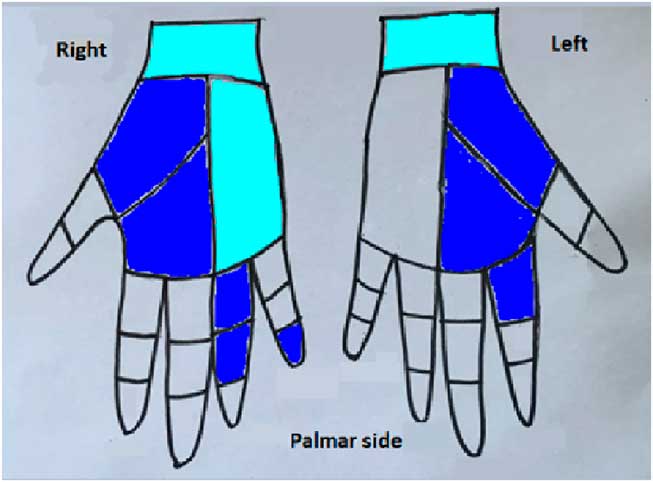

Hand hygiene performance scores were different between the 2 assessments (Table 3). Comparison of hand hygiene scores (0, uncleaned zones; 1, cleaned zones) showed improvement for the dorsal sides of both the right (P<.001) and left (P<.001) hands, and for the palmar side of the left hand (P=.002). The areas with the highest and the lowest improvements of hand hygiene quality after SBT are shown in Fig. 2. The less well-washed zones remained the wrists, the finger extremities, and the interdigital spaces.

Fig. 2 Most and least improvement of hand hygiene quality after simulation-based training. Note. ![]() Least improvement of hand hygiene quality.

Least improvement of hand hygiene quality. ![]() Most improvement of hand hygiene quality.

Most improvement of hand hygiene quality.

Table 3 Hand Hygiene With Hygiene Assessment Scores Using the Anatomically Based Assessment Scale

Note. Palm, palmar side; Dors, dorsal side; (R), right hand; (L), left hand.

a Before SBT.

b After SBT.

Notably, there was a significant difference between the 2 assessments for nails. During assessment A, 2 participants performed 9 of 10 procedures, and 1 of these 2 participants always had long or polished nails. During assessment B, on the other hand, all participants had acceptable nails. In other words, nonhygienic nails were observed in 9 of the 218 evaluations (4.13%) during assessment A and in none of the 220 evaluations (0%) during assessment B (P=.002). No differences between the 2 assessments were observed for the other parameters: presence of jewelry (P=.85), long nails (P=.08), and skin wounds (P=.42). There was no correlation between hand hygiene score and level of experience, professional status, left- or right-hand dominance, and experience in a surgical unit (Table 4).

Table 4 Correlation Between Hand Hygiene Scores Obtained on the Anatomically Based Assessment Scale and Population Characteristics (n=22)

Note. Correlation with professional status, dominant hand, level of experience, and previous experience in a surgical unit, used a linear regression analysis based on the Fisher exact test.

Participants took tests before and after the theoretical course. Scores (on a scale of 0 to 5) significantly improved from 2.8 ± 0.2 to 4.4 ± 0.1 between the 2 assessments (P<.01). Participants were very satisfied with the course: on a scale of 0 to 10, satisfaction was 9.5 ± 0.1.

Discussion

Main results

In the present study, we assessed correct and effective hand hygiene knowledge, attitudes, and practices. A theoretical course associated with SBT enhanced compliance with the hand hygiene procedure, which improved the duration of the procedure, especially in the first hand rubbing procedure observed. After the first observation of hand-rubbing performance, this duration decreased over time. Quality of hand hygiene improved, with increased scores of performance and nail hygiene improvement. Nevertheless, using an anatomically based assessment scale for hand hygiene with ABHR, some zones remained insufficiently washed: the wrists, finger extremities, and interdigital spaces. The intervention had no beneficial effects on the other factors associated with poor quality of hand hygiene. To our knowledge, no previous study has assessed the impact of an SBT course in an emergency department, notwithstanding all potential factors of nonadherence. This study is the first to analyze evolution of hand-rubbing duration as the procedure is observed repeatedly.

Main outcome

The average duration of hydro-alcoholic hand rubbing before and after training adhered to the WHO recommendations of 20–30 seconds. 2 At times, average duration exceeded 30 seconds, especially during the first washings. This duration probably increased because participants knew they were being observed and assessed. Few previous studies have analyzed this duration. A French prospective study carried out in 2011 in an intensive care and neonatology unit demonstrated that only one-third of participants were aware of adequate hand rubbing duration before theoretical training.Reference Dicko-Traore, Gire and Brevaut Malaty 4 In recent years, many campaigns on hand hygiene have been carried out by the French Hospital Hygiene Society 8 and various hygiene departments. This may help to explain why duration was followed. Our analysis of hand-rubbing duration in the present study highlights 2 points. First, SBT improved duration, as demonstrated by significant improvement between the 2 assessments before and after SBT from the first through the tenth procedure. However, even after SBT, the duration decreased significantly during repeated procedures without any significant difference between nurses and residents. The WHO has listed some conditions in an ED that may explain the decrease in the duration of hand rubbing over time: overcrowding, high number of opportunities for hand hygiene per hour of patient care, and insufficient time. Therefore, these results highlight the need to analyze hand hygiene in the ED, where specific factors may influence hand hygiene compared to other units.Reference Kuzu, Ozer and Aydemir 12 – Reference Suchitra and Lakshmi Devi 17 These results strongly suggest a need to focus on constant adherence to adequate duration, even when handwashing is repeated. Timing and repeated SBT should improve the procedure. Often, performance is tested before an educational program and then retested.Reference Macdonald, McKillop and Trotter 25 However, to our knowledge, no data, as provided in the present study, have been published regarding the assessment of performance after repeated hand hygiene procedures.

Secondary outcomes

Efforts to improve hand hygiene involve more than the duration of hand rubbing.Reference Zanni 26 They also include following the 7 steps, quality of hand hygiene procedure, nail hygiene, and the removal of jewelry. In the present study, on average, more than the 6 of 7 steps recommended by WHO were carried out during assessments A and B, and participants were made aware of these steps before SBT. Overall, the steps were carried out, but performance of the 7-step hand hygiene procedure does not suffice to achieve an optimal quality of hand hygiene. This training produced significant improvement of performance scores for the hand-rubbing procedure.

The use of the anatomically based assessment scale distinguished the least washed zones, particularly the palmar side of the right hand. In a previous study using a pixel scale, the right hand was less washed than the left one, and the dorsal side was less washed than the palmar side.Reference Garnier, Burger and Salles 21 In the present study, most participants were right-handed, and we speculated that most of them were more adept with the right hand. Thus, we interpreted the lack of improvement in the quality of washing of the right hand as being related to use of the nondominant hand. The fact that the dorsal side was better washed than the palmar side might be explained as follows: the palmar surface of the hand being hollow, we assumed that hand-to-hand rubbing (step 4 of the 7 recommended steps by WHO) may be less effective than rubbing the dorsal surface (step 3). We also assumed greater contact surface when washing the dorsal side of one hand by the palmar side of the other. There was no correlation between hand hygiene quality and dominant hand in the present study. Our results do not indicate a difference between left- and right-handed participants, as previously suggested in the literature.Reference Garnier, Burger and Salles 21

Moreover, after training, the less well-washed zones remained the wrists and the finger extremities, as previously described.Reference Garnier, Burger and Salles 21 , Reference Ramón-Cantón, Boada-Sanmartín and Pagespetit-Casas 27 Based on an assessment scale concerning 6 hand areas, Ramón-Cantón et alReference Ramón-Cantón, Boada-Sanmartín and Pagespetit-Casas 27 found that the fingers, thumbs and wrists had significantly lower scores than those obtained for other areas of the hand. Garnier et alReference Garnier, Burger and Salles 21 obtained similar results based on a pixel scale. In the present study, interdigital spaces were cleaned less. To our knowledge, no other study has highlighted these zones because no other scales specifically include these spaces. Focusing on these points during theoretical courses would improve the quality of hand hygiene. The benefit of the SBT course was attested by improved in posttest scores. A previous study yielded similar results.Reference Macdonald, McKillop and Trotter 25 , Reference Rubanprem Kumar, Aruna and Sasikala 28

Some authors have assessed correct and effective hand hygiene knowledge, attitudes, and practices with questionnaires.Reference Alex-Hart and Opara 29 – Reference Sibiya and Gumbo 31 A randomized controlled trial carried out in Spain showed that hand hygiene compliance among primary healthcare providers could be improved using a multimodal hand hygiene approach, including theoretical and practical workshops.Reference Martín-Madrazo, Soto-Díaz and Cañada-Dorado 32 In the present study, assessment after simulations showed that attitudes (compliance to duration during all procedures) and practices (optimal washing of neglected areas of the hand) needed to be improved. The present study also showed, contrary to the findings of Macdonald et al,Reference Macdonald, McKillop and Trotter 25 that teaching the 7 steps recommended by the WHO does not suffice. Conclusions of a recent survey also emphasized that the WHO-recommended guidelines should not only be taught but also implemented in the medical field.Reference Zil-E-Ali, Cheema and Wajih Ullah 33 A campaign to raise healthcare worker awareness of the factors associated with inadequate hand hygiene should be reinforced.

In the present study, training made it possible to sensitize the caregivers on the need to be free of nail polish, as suggested in the literature.Reference Ward 34 Jewelry and fingernails longer than 2 mm have been reported to enhance total bacterial count on hands.Reference Fagernes and Lingaas 35 In 2006, a multicenter prospective study carried out by the French Society of Hygiene and the French Society of Anesthesia found that in the operating room, 38% of the 964 anesthesiology physicians and 26% of the 325 nurses wore jewelry.Reference Carbonne, Veber and Ajjar 36 Another French survey reported that 43% of 706 healthcare professionals did not comply with French recommendations on wearing jewelry, and 11.5% on nail hygiene standards.Reference Vandenbos, Gal and Dandine 37 A survey conducted in Poland among 112 students revealed that even if most of them were trained in hand hygiene, >50% wore a wrist watch or jewelry on their hands.Reference Kawalec, Kawalec and Pawlas 38 Surprisingly, in our study, only a few participants were wearing jewelry.

Participants knew that they were being evaluated and videotaped; a factor that could have modified their usual behavior. Finally, the lack of correlation of hand hygiene score with level of experience or professional status indicated that all caregivers should be concerned by such training sessions. Equally surprising, the present results suggested that, in all participants who had previous experience in an operating room or surgical unit practice where caregivers are expected to be sensitized to hand hygiene, a better quality of hand hygiene was not shown. Consequently, hand hygiene quality might not be constant over time.

These results reinforce the necessity of SBT as a means of maintaining a high quality of hand hygiene. Analysis of correct and effective hand hygiene in Iran underscored the need for improvement in the existing training program aimed at addressing the gap in knowledge, attitudes, and practices.Reference Nabavi, Alavi-Moghaddam and Gachkar 39

External validity

The present study was carried out in a pediatric emergency department. This intervention could also be applicable in an adult environment where medical activity is unpredictable, such as emergency, intensive and critical care units. Similarly, it would be interesting to evaluate the quality of hand hygiene procedures in units with programmed activities.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size of participants was small, and physicians did not agree to participate to the study. Consequently, it was not possible to compare performance between nurses and physicians or between physicians and residents. Another limitation might be the overestimation of hand hygiene quality because participants knew they were being observed and assessed. When they are being observed, healthcare providers are likely to improve their usual practice.Reference Guilbert 40

In conclusion, in this prospective study an educational program combining theoretical and SBT courses improved performance in hand hygiene in terms of duration, performance, scores, and nail hygiene. In addition, these findings highlight the use of an anatomically based assessment scale for hand hygiene with ABHR to pinpoint the least-washed zones. They also emphasize the need to repeat hand hygiene during simulations to ensure that procedure duration is followed. Hand hygiene is essential for reducing of the spread of infections. However, management of life-threatening situations might not always allow the time required for efficient hand hygiene. Although working in a pediatric emergency department is a factor that contributes to noncompliance to hand hygiene procedures, SBT can improve hand hygiene quality. The present study highlights the need for future development of such programs in units or departments with nonprogrammed healthcare activities.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2018.229

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jeffrey Arsham, an American medical translator, for reviewing the English-language text. The authors would like to thank Olivia Stephan RN, an emergency nurse in the University Hospital of Bichat who lived 10 years in England, for rereading and reviewing the manuscript. The authors would also like to thank Maximilien Guericolas, a native American speaker and emergency physician working in the University Hospital of Bichat, for rereading and reviewing the manuscript.

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.