Norovirus infections are an increasingly recognized cause of diarrhea in hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT) recipients; they are associated with prolonged periods of symptoms and viral shedding, high morbidity, and occasionally mortality.Reference Bok and Green1–Reference van Beek, van der Eijk and Fraaij5 Although norovirus is a well-recognized cause of hospital clusters of gastrointestinal illness, data on the containment of nosocomial norovirus clusters in HSCT populations are limited. Standard infection prevention strategies for preventing and controlling norovirus in nonimmunocompromised settings include hand washing with soap and water, environmental cleaning with bleach, unit closure, staff education, and staff screening for symptoms with requirements to stay home if found to have gastrointestinal illness.Reference Barclay, Park and Vega6,7 However, the effectiveness of these strategies for controlling a cluster in the HSCT population, in whom the duration of symptoms and shedding is much longer and the risk of transmission is higher, is not well characterized.Reference Doshi, Woodwell, Kelleher, Mangan and Axelrod8

From January through May 2012, we identified a cluster of laboratory-confirmed norovirus infections among patients admitted to the HSCT unit. One patient with nosocomially acquired norovirus died secondary to the infection, prompting a review of infection prevention programs and implementation of new processes to reduce future transmissions.

Methods

Setting

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) is an academic tertiary-care center with a 28-bed inpatient HSCT unit (20 of 28 were single-room occupancy) during the study period. The HSCT unit is a restricted-access unit in a building that is separate from most of the medical-surgical inpatient beds.

Population and data collection

All patients admitted to the HSCT unit during the study period from January 1 through May 31, 2012 were included. Demographic, administrative, pharmacy, and laboratory data were extracted electronically. Clinical variables, including gastrointestinal symptoms (GIS), were manually abstracted.

Description of outbreak and case-cohort study

An epidemic curve was generated, then a retrospective case-cohort study was conducted to identify risk factors for norovirus acquisition, including the role of facility factors, such as bed location. The primary outcome was laboratory-confirmed norovirus. Cases were matched to all patients admitted to the HSCT unit with GIS. Patients tested for norovirus and found to be positive were also compared to patients who were tested for norovirus and found to be negative.

Case definitions

Gastrointestinal symptoms were defined as any patient with loose stools at least 3 times per day and/or vomiting for at least 48 hours.Reference Schwartz, Vergoulidou and Schreier3,Reference Doshi, Woodwell, Kelleher, Mangan and Axelrod8,Reference Robles, Cheuk, Ha, Chiang and Chan9 Details of the norovirus case definition are included in the supplementary materials (Supplementary Table 1) and included fever, new GI complaints, and testing results. Norovirus testing was performed at the discretion of the treating clinician and thus not available for all GIS patients.

Infection control measures

Standard infection prevention protocols on the HSCT unit prior to January 2012 included hand hygiene with alcohol-based hand rub or soap and water; hand hygiene monitoring via product usage measurementReference Branch-Elliman, Snyder and King10 validated with intermittent direct observation; cleaning of patient and common areas with quaternary ammonium-based disinfectants; and active screening and restriction of visitors with symptoms of viral infection. All patients with presumed norovirus are placed on contact precautions, and bleach cleaning daily and after discharge was and remains standard for patients with norovirus. A hospital-wide “no shared food” policy was in effect during the study period. In addition, staff members with GIS are given early access to sick leave and are not required to use 3 vacation days before they can access sick-leave pay. This policy is designed to encourage compliance with recommended absence from work to limit spread of infection.

Statistical analysis

Risk factors for norovirus acquisition were evaluated using the χ2 test and the Fisher exact test for categorical variables and analysis of variance (ANOVA) as well as the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. All analyses were performed using Stata version 12.0 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

From January 1, 2012, through May 31, 2012, 148 patients were admitted to the HSCT unit (Fig. 1). Of these, 99 (66.9%) patients had GIS, including 48 patients (48.5%) who were tested for norovirus using enzyme immunoassay (EIA). Of 48 samples, 7 (14.6%) were positive (Supplementary Table 2 online). Of the 99 patients with GIS, 84 (84.9%) were tested for Clostridioides difficile and 10 (11.9%) were positive; none had confirmed norovirus. Two GIS patients were admitted to the ICU and 1 patient died from norovirus infection. No other nosocomial clusters on other inpatient units were identified during the study period.

Fig. 1. Description of full cohort and case selection.

The epidemic curve and distribution of cases in the unit suggested point-source transmission with contamination of a limited environmental area (Fig. 2). The only patient with GIS present on admission was the index case. Among the 6 subsequent cases, 2 cases occurred in the same room as the index patient and 1 case occurred in an adjacent room after a median 9-day inpatient stay. Room location was the only significant predictor of infection acquisition (Table 1 here and Supplementary Fig. 1 online).

Fig. 2. Norovirus epidemic curve.

Table 1. Differences Between the Patients With Severe Gastrointestinal Symptoms Who Were Tested and Not Tested by Norovirus Enzyme Immunoassay, and Between the Patients Who Tested Positive and Negative for Norovirus

Note. HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplant; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin.

a Index case not included in the calculation.

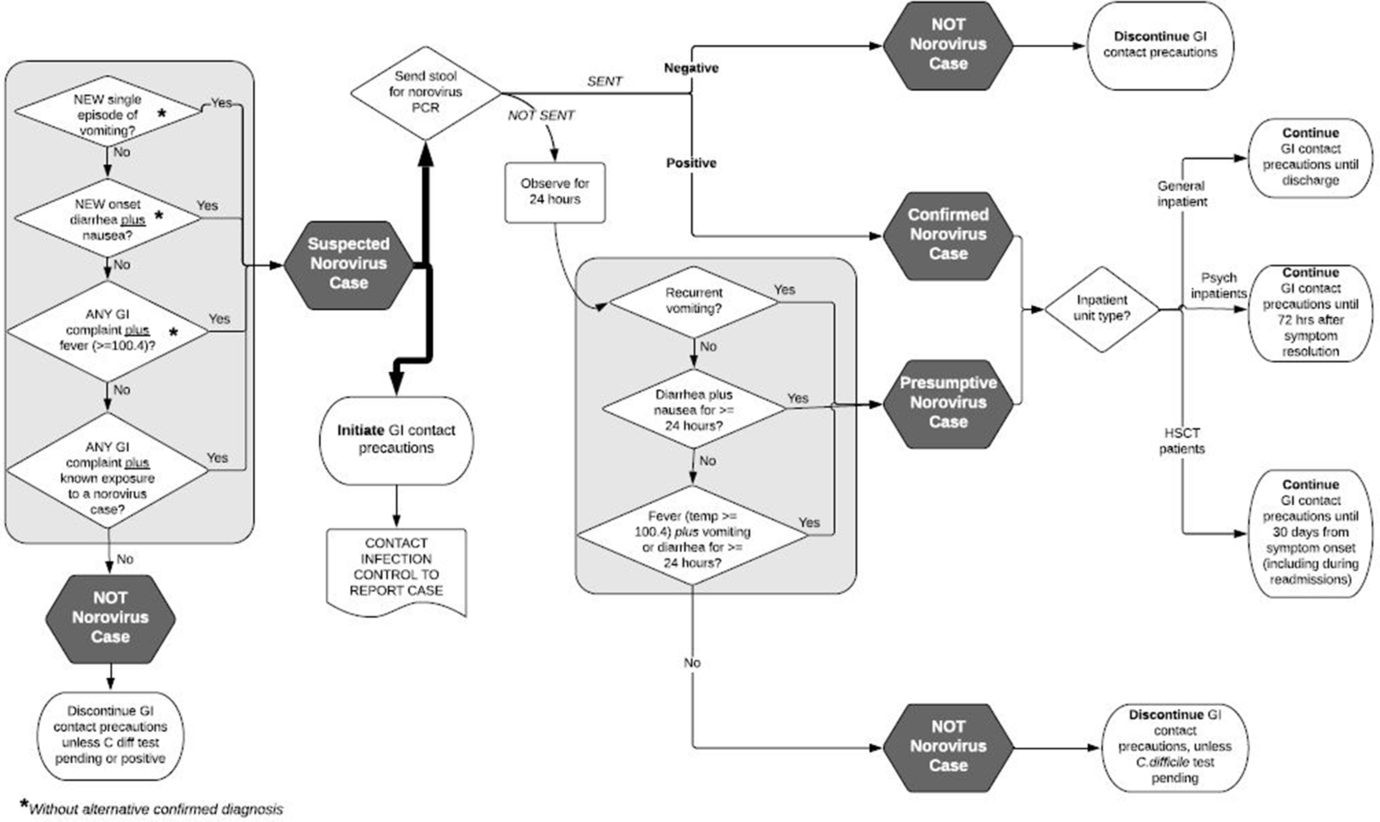

Bundle and outbreak control

After the first nosocomial norovirus case was identified, an enhanced infection control bundle was instituted. The bundle included hand washing with soap and water followed by alcohol-based hand rub; enhanced environmental cleaning with bleach, including in all common areas and bathrooms; direct observation of the postdischarge and daily cleaning process by infection control and/or hospital epidemiology (IC/HE) personnel; norovirus education for clinical staff, patients, and visitors; symptom screening with work restriction for clinical staff and visit restriction for visitors; and enhanced surveillance for additional cases by IC/HE personnel. The screening process was triggered after the identification of a nosocomial case and was performed by unit staff on every shift. The process includes a strict case definition with high sensitivity applied to patients and hospital staff and an algorithm for testing and identification of norovirus cases (Fig. 3). Any patients with symptoms were isolated and tested; any staff were removed from work for 72 hours after their last symptom and were given access to extended sick-leave pay immediately. Screening continued until transmission was no longer detected. Because HSCT patients shed virus for prolonged periods and are frequently readmitted, contact precautions were extended to a 30-day window following symptom onset rather than until discharge. To assist with isolation on subsequent admissions, HSCT patients with norovirus are flagged in the electronic medical record. Enhanced postdischarge cleaning protocols were developed, including direct observation of the rooms prior to occupancy by the next patient, in addition to the standard bleach cleaning for all rooms with norovirus patients.Reference Greig and Lee11 Finally, in-house norovirus polymerase chain reaction (PCR) replaced EIA to improve the speed and accuracy of detection of cases.

Fig. 3. Inpatient gastrointestinal syndrome/norovirus evaluation and precautions algorithm. Contact precautions indicate gastrointestinal syndrome precautions, including patient isolation, gown and glove for all room entry, and hand washing with soap and water followed by alcohol-based hand rub after room exit in the setting of a cluster.

Since the implementation of enhanced infection prevention measures, including the newly developed protocol, no additional healthcare-associated cases have been identified on the HSCT unit.

Discussion

In this norovirus cluster on the inpatient HSCT unit, the only significant factor associated with nosocomial norovirus acquisition was room location, congruent with other studies that established the importance of proximity and room contamination in healthcare-associated clusters.Reference Doshi, Woodwell, Kelleher, Mangan and Axelrod8,Reference Harris, Lopman, Cooper and O’Brien12 Nenonen et alReference Nenonen, Hannoun and Svensson13 demonstrated that, among hospital wards experiencing an outbreak, 47% of environmental swabs in the affected ward were positive for norovirus, compared with only 7% in the unaffected ward. Positive pressure ventilation present in HSCT units but not standard hospital floors may also play a role in environmental contamination in this population by distributing aerosols outside a patient’s room.Reference Alsved, Fraenkel and Bohgard14 These results highlight the importance of early recognition and diagnosis of norovirus in the HSCT population, given the potential for rapid and sustained spread of norovirus long after the index patient has been discharged.

Based on our own findings and earlier studies on outbreaks in HSCT, we implemented a novel infection prevention protocol, which included a strict definition of norovirus infection that permitted earlier and broader implementation of control measures. This protocol successfully terminated the cluster and prevented outbreaks in subsequent norovirus seasons. The strict definition included in the triaging algorithm, which was designed to be extremely sensitive but have low specificity, was an important element of the infection prevention strategy because our data suggested that clinicians often did not consider norovirus as a potential cause of severe GIS in this population and that early identification is critical for preventing clusters (Fig. 3). Other causes, such as C. difficile infection, were more likely to be tested and evaluated. In addition to the highly sensitive case definition, strict screening of staff and patients was undertaken to ensure that cases were identified early in the disease course.

In the years following the implementation of this bundle, no additional healthcare-associated transmissions have been detected on the HSCT unit, and the protocol has been rolled out in a modified form to other units with no additional sustained nosocomial clusters of infection in our facility.

Many of the interventions included in the infection prevention protocol are cost-saving measures, even at very low effectiveness (10%) for preventing additional norovirus transmissions.Reference Lee, Wettstein and McGlone15 Healthcare-worker presenteeism is an important factor in nosocomial outbreaks, including on transplant and immunocompromised patient wards; thus our screening protocol was applied to patients and staff.Reference Doshi, Woodwell, Kelleher, Mangan and Axelrod8 Healthcare-worker screening and mandated time off if GIS develop is another intervention that may be both clinically effective and cost-saving, even with paid time off and early access to paid sick leave, depending upon the cause of the outbreak.Reference Lee, Wettstein and McGlone15 Ward closure is another strategy that has been used to manage and prevent healthcare-associated transmissions; however, modeling studies suggest that this strategy is more expensive than other infection prevention interventions and are only cost-saving if prevention effectiveness exceeds 90%.Reference Lee, Wettstein and McGlone15 Beyond cost-effectiveness, due the specialized nature of the HSCT unit, moving these immunocompromised patients to other hospital wards is often not feasible due to facility constraints; thus, ward closure may not be a practical option.

Another important finding was the limited testing for—and identification of—norovirus in the HSCT population.Reference Roddie, Paul and Benjamin16 Due to the frequency of GIS in this population and the multitude of infectious and noninfectious cases, differentiating norovirus from other causes of GIS is challenging. Among the 99 patients with severe GIS, only 48 (48%) were tested for norovirus, but most were tested for other types of infections, including C. difficile and Enterobacteriaceae. These results align with those of prior studies suggesting that GIS are often misdiagnosed as other infections, including C. difficile. Reference Koo, Ajami and Jiang17,Reference MacAllister, Stednick, Golob, Huang and Pergam18 Thus, education of staff is of critical importance, especially during norovirus season, to identifying cases and to implementing infection prevention strategies as soon as infections begin to occur. Electronic systems can be leveraged for early case ascertainment and intervention by helping to identify cases early in their course and to encourage testing and isolation before substantial environmental contamination and nosocomial transmissions have occurred. Another important diagnostic intervention is the use of PCR, rather than EIA, to confirm cases. The sensitivity and specificity of EIA are both poor, potentially leading to many missed cases before transmission is identified.

This study was limited by small sample size and retrospective design, the limited number of patients who were tested for norovirus, and the diagnostic test itself (EIA during the study period), which has poor sensitivity and specificity. Thus, it is feasible that the cluster may have been larger and that factors other than environmental contamination may have also played a role. However, limited testing and poor predictive value of the test are likely to bias findings toward the null rather than toward finding an effect; thus, it is unlikely that either of these factors caused a false-positive association between environmental exposure and norovirus acquisition. Another possible source of norovirus was staff presenteeism, particularly for the cases that occurred parts of the HSCT unit that were not in close proximity to the index case room (Supplementary Fig. 1 online). However, we did not find any specific evidence of a healthcare-worker source for this cluster. Because infection prevention interventions were bundled, we were not able to determine which, if any, individual interventions were the most important. However, given the strong association between location and acquisition, improved environmental cleaning coupled with the aggressive screening protocol is likely to have played a major role in ending the outbreak.

In conclusion, norovirus presents similarly to other causes of GIS in the HSCT population, leading to delayed diagnosis and environmental contamination. Use of a standard algorithm for earlier identification of presumptive cases of GIS may help prevent future norovirus outbreaks.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2020.21

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr David S. Yassa MD, MPH, Infection Control/Hospital Epidemiology staff members, and the clinical staff in the Bone Marrow Transplant Unit for their assistance in developing and implementing protocols that led to the successful control of this outbreak.

Financial support

W.B.E. is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (grant no. NHLBI 1K12HL138049-01).

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.