Peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) are increasingly used in hospitalized and outpatientsReference Chopra, Kuhn, Flanders, Saint and Krein1,Reference Johansson, Hammarskjöld, Lundberg and Arnlind2 as a safe and effective alternative to other types of central venous catheters.Reference León, Alvarez-Lerma and Ruiz-Santana3–Reference León and Ariza5 Major PICC-related complications, including mechanical failure, catheter-associated bloodstream infection (CABSI), and venous thrombosis, are concerning.Reference Chopra, Anand, Krein, Chenoweth and Saint6,Reference Chopra, Anand and Hickner7 However, risks for CABSI remained poorly defined, and incidence rates of catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI) differ across studies,Reference Zhao, Griffith and Blumberg8,Reference Sakai, Kohda and Konuma9 particularly due to discrepancies among definitions of CRBSI.Reference Tomlinson, Mermel, Ethier, Matlow, Gillmeister and Sung10 In a study of 1,034 clinically defined CRBSIs, only 40% of the CRBSI diagnoses were supported by the paired blood-culture positivity criteria, and only 6% were supported by a positive catheter tip.Reference Tribler, Brandt and Hvistendahl11 To avoid the interchangeability of CABSI and CRBSI concepts, especially in the absence of catheter removal, many authors use CRBSI only with the remaining episodes being categorized as primary bacteremia (PB).Reference Mermel, Allon and Bouza12–Reference Eggimann, Pagani and Dupuis-Lozeron14 However, ambiguity regarding the clinical impact of CABSI and the risks of PICC-related complications remains.Reference Bessis, Cassir and Meddeb15–Reference Grau, Clarivet, Lotthé, Bommart and Parer17

We designed a prospective cohort study to assess the incidence, risk factors, and impact on outcome of infectious and thrombotic complications in adult patients with PICCs.

Methods

Design and participants

A single-center prospective cohort observational study was carried out between January 1, 2013, and November 30, 2017, in an acute-care 600-bed teaching hospital (reference population, 250,000) located in Seville, Spain. The primary objective was to determine the incidence, time to appearance, and risk factors of major PICC-related infectious and thrombotic complications. Secondary objectives were the rate and incidence density of complications, causative pathogens, and crude and attributable mortality. This study was approved by the institutional review board, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consecutive adult inpatients and outpatients aged ≥18 years who had a PICC inserted between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2016, and for whom follow-up was conducted by November 30, 2017, were eligible. Only the first PICC inserted was considered for each patient. Exclusion criteria for PICC insertion were life expectancy <7 days, anatomical abnormalities of the venous system of the upper extremities, bilateral upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis (UEDVT), lymphedema, or skin infection at the site of insertion. The following exclusion criteria were applied: patients aged <18 years, PICCs not placed in the peripheral veins of the upper extremity, and refusal to provide written informed consent to participate.

Study procedures

All PICCs were inserted as an elective procedure using a PowerPICC Catheters (Bard Access Systems, Salt Lake City, UT). The PICC catheterization inserted by an experienced intensivist was performed by ultrasound-guided puncture of the deep veins in the upper mid-arm using a standard 10 MHz linear ultrasound probe, maximal barrier, and strict sterile precautions.Reference O’Grady, Alexander and Burns13,Reference Tian, Zhu, Qi, Guo and Xu18,Reference Pittiruti, Hamilton, Biffi, MacFie and Pertkiewicz19 The position of the catheter tip was assessed during implantation using fluoroscopy or the Sherlock 3CG Tip Confirmation System (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). PICCs were secured in suture-free manner with the StatLock PICC Plus Stabilization Device (Becton Dickinson). Routine prophylaxis of UEDVT according to clinical practice guidelines was not performed.Reference Lyman, Bohlke and Falanga20 A standardized protocol of PICC care and maintenance, with aseptic techniques used at all times, was applied.Reference O’Grady, Alexander and Burns13 After catheter insertion, patients were followed during their hospital stay and thereafter by telephone contact at 1, 3, and 6 months after PICC placement using an ad hoc questionnaire. After 6 months, the patient’s family physician contacted us to report any complication, and we also made frequent nonprotocolized telephone calls until the catheter was removed or until November 30, 2017, if the catheter was still in place at the end of the study. Catheters with confirmed or suspected CABSI were considered for antibiotic lock. Antibiotic lock was carried out with vancomycin 1–2 mg/dL for 14 days, and alcohol lock was performed with ethanol (70%) for 24 hours.Reference Bestul and Vandenbussche21

Definitions

CABSI was defined as either CRBSI or PB. CRBSI was diagnosed in a patient with PICC and clinical manifestations of infection (fever >38°C or <35°C, or hypotension) with at least 1 positive blood culture (bacteremia or fungemia) and isolation of the same microorganism in the peripheral blood and the catheter tip (semiquantitative culture, ≥15 colony-forming units [CFU]/mL), or a differential time to positivity of ≥120 min. PB was diagnosed in a patient with PICC and clinical manifestations of infection (fever >38°C or <35°C, or hypotension) with at least 1 positive blood culture (bacteremia or fungemia) and negative catheter culture (or not performed)Reference Mermel, Allon and Bouza12,Reference Eggimann, Pagani and Dupuis-Lozeron14 without signs or symptoms of another documented source of infection. For common skin contaminant 2 or more positive blood cultures with the same microorganism on separate occasions were required.Reference Mermel, Allon and Bouza22 Symptomatic UEDVT (pain, swelling, redness, or alteration of the venous flow) with suggestive signs of partial or complete obstruction of the vein confirmed by Doppler ultrasound studies were only considered in the group of thrombotic complications. Catheter dwell time was the number of days between catheter insertion and removal. Incidence density was defined as the number of episodes (or events) per 1,000 catheter days. Hospitalized patients were inpatients referred for PICC placement. Outpatients were those referred to the hospital for PICC placement who returned home after the insertion procedure. Mortality attributable to CABSI was defined in the presence of documented bacteremia before the death of the patient, assuming that the progression of infection was the cause of death.Reference Ziegler, Pellegrini and Safdar23

Data collection

The following demographic data were recorded: type of patient (hospital ward or outpatient setting referral for PICC insertion); underlying disease; indication of PICC; laterality of PICC placement; vein accessed; catheter-related characteristics; tip position; reasons for PICC removal related to the catheter (eg, local infection, obstruction, phlebitis, CRBSI, and UEDTV); reasons for PICC removal unrelated to the catheter (eg, end of intravenous therapy, accidental withdrawal, intolerance, not confirmed suspicion of CRBSI, and death); complications during insertion; complications during use (eg, CRBSI, PB, UEDTV, local infection, phlebitis, catheter colonization); and mortality.

Statistical analysis

In patients with 2 simultaneous major complications, infection (CRBSI) and thrombosis (UEDVT) were considered independent events and were analyzed separately. When PB was followed by a CRBSI, only PB was considered. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) or as median and interquartile range (IQR, ie, 25th–75th percentile). Categorical variables were compared using the χReference Johansson, Hammarskjöld, Lundberg and Arnlind2 test or the Fisher exact test, and continuous variables were compared using the Student t test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Logistic regression analysis was used to assess risk factors for outcome. Those variables with P < .10 in univariate testing were entered into the model. Catheter lifetime was defined as the number of days from insertion to catheter failure. Failure included local infection, obstruction, deep venous thrombosis, suspicion of CRBSI, phlebitis and intolerance. Otherwise, the observation was considered right censored. Survival curves according to the levels of several factors were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and were compared using the log-rank test. To obtain the proportional hazard model by the catheter lifetime, a selection of variables based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC) was carried out. Probability density functions for the catheter lifetime in the groups CRBSI and PB (considering catheter removal due to suspected CRBSI as failure) were estimated using the local likelihood approach to density estimation with censored data.Reference Loader24 The study period spanned January 2013 to December 2016. For each of the 16 quarters of the study period, the number of patients in whom the PICC was inserted, the total number of days of exposure (D t) and finally, the number of patients who presented the study event (ie, infectious or thrombotic complications) during the follow-up period (N t) were calculated. To evaluate the evolution of the incidence, it was assumed that the random variable N t followed a Poisson distribution of mean μ t:

Here, s(t) is a smooth function of time, which was nonparametrically estimated by means of a cubic spline. The goodness of fit was evaluated using the overdispersion coefficient, defined as the ratio of the deviance and its degree of freedom. Notably, for each quarter (t = 1, …,16), 1,000 × μt/D t corresponded to the expected number of events per 1,000 catheter days. Also, a subanalysis of the distribution of variables of interest in hospitalized versus outpatients was performed. Statistical significance was set at P < .05. Data were analyzed using the R package software, version 3.6.1.25

Results

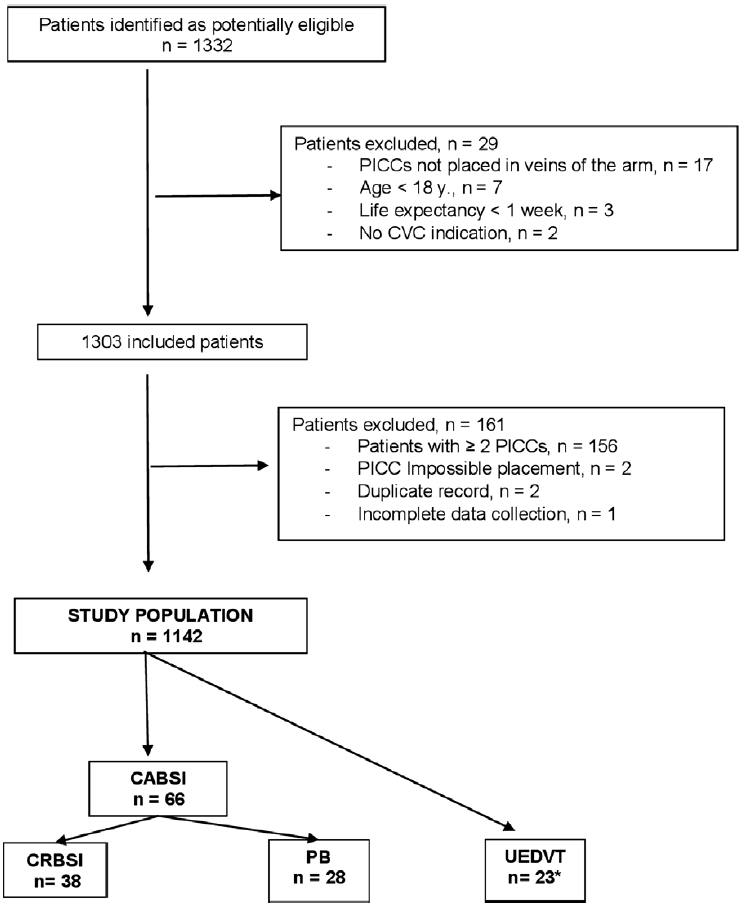

Of 1,332 patients who were candidates for PICC placement during the study period, 1,303 (97.8%) were eligible, but 161 were excluded, mainly because 2 or more PICCs had been inserted (Fig. 1). The study population included 1,142 patients (48.8% men; mean age, 60.4 years [SD, 15.1]. Salient characteristics of patients regarding underlying diseases, indication of PICC, details of implantation, reasons for removal, and complications are shown in Table 1. Briefly, PICCs were placed in 652 (57.1%) hospitalized patients and in 490 (42.9%) outpatients, and chemotherapy (52%) for solid tumors (48.4%) was the main reason for PICC insertion. The total catheter dwell time was 153,191 days, with a median of 79 days (interquartile range [IQR], 20–188). Catheter dwell time was significantly longer in outpatients than in hospitalized patients (median, 164 days [SD, 116–271] vs 25 days [SD, 11–73]; P < .001). Duration of the catheter in place was ≥365 days in 103 patients and ≥730 days in 12 patients, with medians of 465 days (IQR, 409–545) and 916 days (IQR, 808–990), respectively (Supplementary Table 1 online). At the end of the study, PICCs were still in place in 26 (2.3%) patients.

Fig. 1. Overview of the study population. Note. PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter; CVC, central venous catheter; CABSI, catheter-associated bloodstream infections; CRBSI, catheter-related bloodstream infection; PB, primary bacteremia; UEDVT:, upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis. *Two patients presented CRBSI and UEDVT simultaneously.

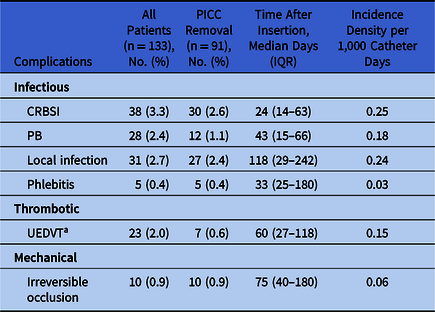

Table 1. Characteristics of Patients, Devices, and Complicationsa

Note. PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter; CRBSI, catheter-related bloodstream infection; PB, primary bacteremia; UEDVT, upper-extremity deep-vein thrombosis.

a Data are expressed as frequencies and percentages unless otherwise stated.

b 2 patients presented UEDVT and PB simultaneously.

c Assessed in 175 patients.

PICCs were removed in the absence of catheter failure in 928 (81.3%) patients because of the end of IV therapy in 644 patients (56.4%) and death in 284 patients (24.9%), with median dwell times of 104 days (21–178) and 50 days (12–185), respectively. Other reasons included unconfirmed suspicion of CRBSI (median dwell time, 51 days; incidence density, 0.38), PICC intolerance (median dwell time, 41 days; incidence density, 0.07), and accidental withdrawal (median dwell time, 47 days; incidence density, 0.18) (Table 1).

Infectious complications

During the follow-up of 1,142 patients, CABSI was diagnosed in 66 patients (5.8%), 38 (3.3%) of whom met the criteria for CRBSI; the remaining 28 patients (2.4%) were diagnosed with PB. Microbiological findings are shown in Table 2. Gram-positive pathogens were the predominant causative microorganisms (71.2%), followed by gram-negative microorganisms (24.2%) and fungi (4.6%). Median days from PICC insertion to CRBSI was shorter for infections caused by gram-positive pathogens (21 days) than for infections caused by gram-negative pathogens (58 days).

Table 2. Microbiological Findings and Days to Bloodstream Infection

Note. PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter; CABSI, catheter-associated bloodstream infection; CRBI: catheter-related bloodstream infection; PB: primary bacteremia.

a Days elapsed from PICC insertion until taken a positive blood culture.

b Associated with an episode of upper extremity deep vein thrombosis (UEDVT).

The incidence densities for CABSI, CRBSI, and PB were 0.43, 0.25, and 0.18, respectively. The median times to infection were 24 days (IQR, 14–63) for CRBSI and 41 days (IQR, 15–66) for PB (Fig. 2). All patients with bacteremia received systemic antimicrobial treatment. The PICC was not removed from 8 patients (21%) with CRBSI and from 10 patients (35.7%) with PB. In these patients, a catheter antibiotic lock protocol was used.

Fig. 2. Probability density functions for PICC lifetime fitted by local likelihood approach with censored data. The maximum of the density function is reached at day 24 for CRBSI (day of maximum flow of failures) and at day 41 for PB. The UEDVT density function was constant and did not reach a maximum value. Note. PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter; CRBSI, catheter-related bloodstream infection; PB, primary bacteremia; UEDVT, upper-extremity deep-vein thrombosis.

In the 8 patients with a CRBSI, 6 catheters were locked with ethanol and 2 with antibiotics; they remained in place for a median of 31 days (IQR, 7–336). The catheters were removed due to local infection after alcohol-lock therapy in 1 case, at end of therapy in 3 cases, and after death in 4 cases. In the 10 patients with PB, 7 catheters were locked with antibiotics and 3 with ethanol; they and remained in place for a median of 109 days (IQR, 23–218). These catheters were removed due to the end of therapy in 4 cases, after death in 2 cases, due to intolerance without apparent infection in 2 cases, due to repetitive episodes of bacteremia in 1 case, and due to secondary bacteremia in 1 case.

Compared with outpatients, hospitalized patients demonstrated a significantly higher rate of both CRBSI (4.6% vs 1.6%) and PB (3.2% vs 1.4%) (P < .001), and they had a higher relative risk (RR) for either CRBSI (RR, 8.51; 95% CI, 3.90–18.57) or PB (RR, 6.81; 95% CI, 2.89–16.02). In the multivariate analysis, independent risk factors for CRBSI and PB were the use of parenteral nutrition (OR, 3.40; 95% CI, 1.77–6.52) and admission to the hematology ward (OR, 4.90; 95% CI, 2.25–10.71), respectively (Table 3).

Table 3. Risk Factors for Infectious and Thrombotic Complications in Patients With PICCs

Note. PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter; CRBSI, catheter-related bloodstream infection; PB, primary bacteremia; UEDVT, upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis.

a Likelihood ratio test.

Thrombotic complications

During the follow-up of 1,142 patients, UEDVT was diagnosed in 23 patients (2.0%) (in association with CRBSI in 2 patients). The incidence density was 0.15 and the median time to UEDVT was 60 days (range, 27–118). As shown in Figure 2, in contrast to infectious complications, the UEDVT density was constant and did not reach a maximum value. All patients were treated with low-molecular-weight heparin. UEDVT was more frequent in outpatients (n = 16, 0.15%) than in hospitalized patients (n = 5, 0.11%; RR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.26–1.94). In the multivariate analysis, independent risk factors for UEDVT were admission to the hematology ward (OR, 12.46; 95% CI, 2.49–62.50) or the oncology ward (OR, 7.89; 95% CI, 1.78–35.16) (Table 3).

Complications leading to PICC removal

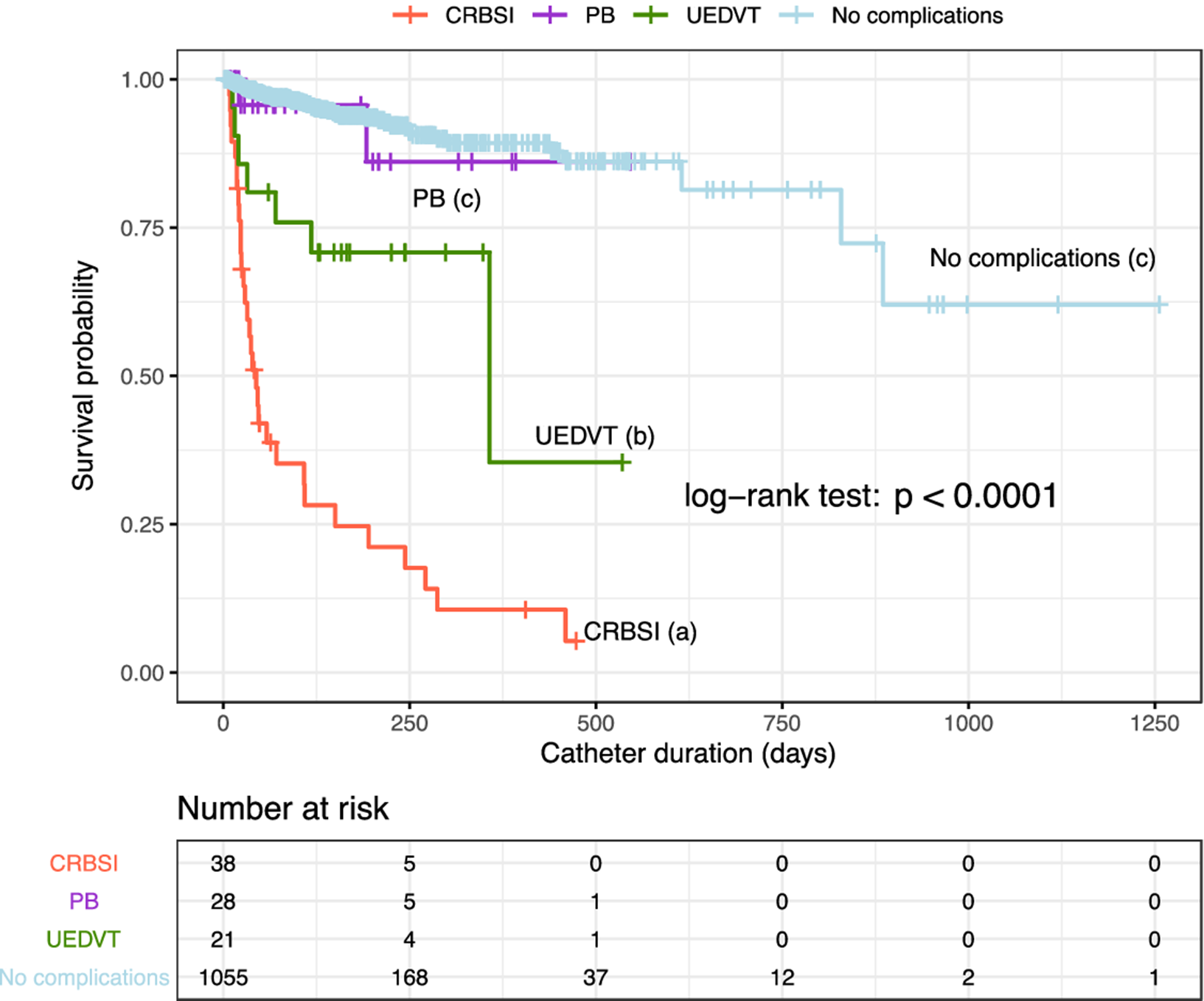

During the follow-up of 1,142 patients, complications related to PICC occurred in 133 patients (11.6%), leading to catheter removal in 91 patients (8.0%). As shown in Table 4, the PICC was removed from 74 of 102 patients with infections, from 7 of 23 patients with UEDVT, and from all 10 patients with irreversible mechanical occlusion. In the multivariate analysis, the statistically significant independent factors for PICC failure and removal were CRBSI (hazard ratio [HR], 14.39; 95% CI, 8.92–23.20) and UEDVT (HR, 2.30; 95% CI, 1.07–4.93), whereas catheter use for chemotherapy was inversely associated with removal (HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.24–0.63). Survival curves for PICCs according to complications are shown in Figure 3. We detected statistically significant differences in the probability of PICC survival between the groups of CRBSI and UEDVT compared to the PB group and those without complications. Catheter probability survival rates for the PB group and for those without complications were similar.

Table 4. PICC Removals Due to Complications

Note. PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter; CRBSI, catheter-related bloodstream infection; PB, primary bacteremia; UEDVT, upper extremity deep vein thrombosis.

a 2 patients presented CRBSI and UEDVT simultaneously.

Fig. 3. Survival curves of PICCs according to the classification of major complications. Note. PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter; PB, primary bacteremia; UEDVT, upper extremity deep vein thrombosis; CRBSI, catheter-related bloodstream infections. Different letters (a, b, and c) indicate significant differences (P < .001).

Mortality

The overall crude and the first 30 days after PICC insertion mortality rates were

were 24.9% (n = 284) and 10.4% (n = 119), respectively. The attributable mortality rate was 0.2%, corresponding to 2 patients with PB caused by Bacteroides fragilis and Staphylococcus aureus in whom septic shock was the cause of death. Compared with outpatients, hospitalized patients demonstrated a higher crude mortality rate (28.4% vs 20.2%; P = .002) and higher mortality at 30 days (16.6% vs 2.2%; P < .001).

Discussion

In a large population of 1,142 adult, consecutive, and unselected inpatients and outpatients undergoing a PICC insertion procedure, major infectious complications had differential features regarding incidence, time to appearance, and risk factors.

Moreover, CRBSI demonstrated an incidence density of 0.25 per 1,000 catheter days, which is lower than figures reported in other studiesReference Grau, Clarivet, Lotthé, Bommart and Parer17,Reference Chopra, Ratz, Kuhn, Lopus, Chenoweth and Krein26–Reference Bertoglio, Faccini, Lalli, Cafiero and Bruzzi28 but quite similar to recent studies that report rates close to zero.Reference Ruiz-Santana, Saavedra and León29,Reference Santacruz, Mateo-Lobo and Riveiro30 In contrast to these aforementioned studies,Reference Grau, Clarivet, Lotthé, Bommart and Parer17,Reference Chopra, Ratz, Kuhn, Lopus, Chenoweth and Krein26–Reference Santacruz, Mateo-Lobo and Riveiro30 57% of patients were hospitalized patients, and 3 of 4 episodes of CRBSI developed during the hospital stay, a rate 4 times greater than the CRBSI rate among patients at home, but still much lower than in other reports.Reference Chopra, O’Horo, Rogers, Maki and Safdar16 In the present study, CRBSI started to occur on day 5 after implantation, with increasing rates during the first 3–4 weeks and maximum density of infection at 24 days, which is consistent with data reported by other researchers studying CLABSIReference Chopra, Anand, Krein, Chenoweth and Saint6,Reference Chopra, Ratz, Kuhn, Lopus, Chenoweth and Krein26,Reference Herc, Patel, Washer, Conlon, Flanders and Chopra31 and CRBSI.Reference Bessis, Cassir and Meddeb15 However, in cancer patients treated at home with parenteral nutritionReference Ruiz-Santana, Saavedra and León29 or chemotherapy,Reference Bertoglio, Faccini, Lalli, Cafiero and Bruzzi28 CRBSI developed later, from 76 to 97 days following PICC insertion. The incidence density of PB was 0.18 per 1,000 catheter days; 3 of 4 episodes occurred during hospitalization and showed a similar pattern to CRBSI, with a maximum density of infection at 41 days. Thereafter, the incidence decreased markedly for both CRBSI and PB. Gram-positive bacilli were the causative pathogens in 2 of 3 episodes of CRBSI and PB, which is consistent with data reported in other studies.Reference Lee, Kim and Kim32 The adherence to guidelines on the care and maintenance of PICCs once they are in placeReference O’Grady, Alexander and Burns13 over the first 6 weeks are crucial, especially in hospitalized patients.

A distinctive feature of this study is the independent analysis of the characteristics of major infectious complications. Also, in the present study, like others,Reference Bessis, Cassir and Meddeb15,Reference Grau, Clarivet, Lotthé, Bommart and Parer17,Reference Mollee, Jones and Stackelroth27–Reference Bouzad, Duron, Bousquet and Arnaud33 the diagnosis of CRBSI both in hospitalized and outpatients was based on strict microbiological criteria because of its high specificity.Reference Raad, Hanna, Alakech, Chatzinikolaou, Johnson and Tarrand34,Reference Chen, Lo, Su and Chang35 Therefore, in our study, episodes of PB were registered separately. The percentage of patients with CRBSI was 57.6% (38 of 66 patients), which is in the range of percentages of 42%,Reference Mollee, Jones and Stackelroth27 46%,Reference Tribler, Brandt and Hvistendahl11 and up to 74%Reference Herc, Patel, Washer, Conlon, Flanders and Chopra31 reported in other studies. In relation to risk factors and in agreement with previous reports,Reference Sakai, Kohda and Konuma9,Reference Bessis, Cassir and Meddeb15,Reference Herc, Patel, Washer, Conlon, Flanders and Chopra31,Reference Pongruangporn, Ajenjo and Russo36 receipt of parenteral nutrition through the PICC was significantly associated with CRBSI, and admission to an hematology ward was a predictor of PB, mainly due to gut bacteria translocation.Reference Puleo, Arvanitakis, Van Gossum and Preiser37

Symptomatic UEDVT and confirmed by Doppler ultrasonography occurred in 2% of patients, with an incidence density of 0.15 per 1,000 catheter days. In a case–control analysis of 1,444 adult inpatients who underwent PICC placement, a 3% rate of catheter-associated thrombosis was reported.Reference Moran, Colbert and Song38 In a retrospective cohort study of 966 unique PICC placements, 42 thrombotic events (4.3%), including 9 cases of lower-extremity deep vein thrombosis, were registered.Reference Chopra, Ratz, Kuhn, Lopus, Lee and Krein39 The median time to UEDVT was 60 days (range, 27–118), whereas in the literature, this complication was reported within the first month after PICC implantation.Reference Chopra, Anand and Hickner7 Admission to hematology or oncology wards were risk factors for UEDVT, which is consistent with the presence of active cancer as predictor of PICC-related thrombosis in other studies.Reference Chopra, Kaatz and Conlon40 Early treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin prevented PICC removal in 66.7% of patients.

Attributable mortality rate of PICC-related complications was only 0.2%. An excess crude mortality ratio within 30 days of PICC insertion has been reported,Reference Bessis, Cassir and Meddeb15 which is consistent with a crude mortality of 42% at 30 days found in our study, probably related to the underlying diseases or comorbidities of the patients.

Our study has several limitations. We used a single-center design. Direct management and care of PICCs was performed by different services rather than by the same medical team. The strengths of our study include the prospective design, a large study population followed for 5 years, patient heterogeneity (with up to 40% of cases with nonneoplastic diseases), PICC insertion performed by the same ICU staff using a strict protocol, and robust data analysis.

In conclusion, PICCs were associated with a low rate of infectious and thrombotic complications. Compared with PB, CRBSI showed a higher incidence density per 1,000 catheter days but a shorter median time to infection. Mortality directly attributable to PICC was very low.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2020.1300

Acknowledgments

We thank Marta Pulido, MD, for editing the manuscript and editorial assistance.

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.