Febrile neutropenia is a well-known complication of myelosuppressive chemotherapy occurring in >80% of patients with hematologic malignancies and is associated with a mortality rate of ~10%.1 Current treatment guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommend starting empiric anti-pseudomonal antibiotic therapy for high-risk patients who develop febrile neutropenia. The addition of empiric vancomycin is recommended for patients with local signs of central venous catheter-related infection, blood cultures positive for gram-positive organisms, history of prior infection or colonization with resistant organisms such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), hemodynamic instability, and/or evidence of soft-tissue infection. Initial therapy should also be based on local antimicrobial susceptibilities.1,Reference Freifeld, Bow and Sepkowitz2 At Yale New Haven Hospital (YNHH), vancomycin is utilized as initial empiric treatment of febrile neutropenia with an antipseudomonal agent due to the concern for an increased risk of resistant organisms, such as MRSA and Streptococcus viridans, in this patient population. Once started, stopping empiric vancomycin has been a challenge in antimicrobial stewardship efforts.

Moreover, MRSA nasal swabs have proven to be useful in the de-escalation of anti-MRSA therapy.Reference Perreault, McManus and Bar3 The supporting data for de-escalation of therapy based on a negative MRSA nasal swab was validated in patients with pneumonia, but it has also been expanded to include nonpulmonary infections. The negative predictive value (NPV) of MRSA nasal swabs for pneumonia and nonpulmonary infections approaches 99%.Reference Dangerfield, Chung, Webb and Seville4–Reference Chan, Dellit and Choudhuri8 However, no studies have evaluated the NPV of MRSA nasal swabs in the acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patient population with febrile neutropenia. At YNHH, a MRSA nasal swab is collected when antibiotic therapy is initiated for febrile neutropenia. Negative results are used to guide discontinuation of anti-MRSA antibiotics in patients without a prior history MRSA colonization or infection. The objective of this study was to evaluate the performance characteristic of a negative MRSA nasal swab in the AML population to determine its NPV.

Methods

This retrospective chart review at YNHH included 194 AML patients with a total of 484 discrete admissions who received empiric treatment for febrile neutropenia between February 2013 and October 2018. We included patients who had a MRSA nasal swab during the admission that febrile neutropenia occurred. Febrile neutropenia assessment consisted of central- and peripheral-line blood cultures, urine culture, procalcitonin, and chest radiograph in addition to the MRSA nasal swab on all patients. Each unique patient could have >1 discrete admission included in analysis. Repeat MRSA nasal swabs were done if there was reinitiation of anti-MRSA therapy during the admission and a previous MRSA nasal swab was collected >7 days prior. Patients were excluded if they did not have a MRSA nasal swab collected during the admission or had a history of prior MRSA infection or colonization. For patients who developed an MRSA infection or had a subsequent positive MRSA nasal swab in later admissions, those admissions were excluded from further analysis. This study was performed as a quality improvement initiative and was therefore deemed exempt from approval by our institutional review board.

Febrile neutropenia was defined a IDSA and NCCN definitions.1,Reference Freifeld, Bow and Sepkowitz2 Colonization with MRSA was defined as a positive MRSA sputum culture without evidence of infiltrate on confirmatory radiographic imaging of the chest. Bacteremia was defined as a positive blood culture with MRSA. Other infections in addition to bacteremia were defined using National Safety Healthcare Network definitions.9 Laboratory testing to detect MRSA colonization was performed using PCR and/or culture. Historically at YNHH, culture-based testing was used until October of 2017. After October 2017, PCR was utilized. Given that 2 different testing methods were utilized, the positivity rate between the 2 tests was compared to ensure that there were no major differences.

The performance characteristics for sensitivity, specificity, NPV and positive predictive value (PPV) of a MRSA nasal swabs to predict MRSA infection were evaluated. Sensitivity was defined as the likelihood that the nasal swab was positive when a MRSA infection occurred during the admission. Specificity was defined as the likelihood that when a negative nasal swab was present, no MRSA infection occurred during the admission. The PPV was defined as the probability that a positive nasal swab would be followed by a subsequent MRSA infection during the admission. The NPV was defined as the probability of having a negative nasal swab and no subsequent MRSA infection during the admission.

Results

In total, 202 unique AML patients over a 5-year period were identified. Eight patients were excluded: no MRSA nasal swab obtained (n = 6), prior MRSA infection (n = 1), and prior positive MRSA nasal swab (n = 1). Of those patients, 495 admissions met inclusion criteria, but 11 admissions were excluded due to a prior MRSA infection (n = 7) or a subsequently positive MRSA nasal swab after a prior negative swab (n = 4). The final patient cohort consisted of 195 patients with 484 admissions; their median age was 64 (range, 18–84) and 105 (54%) were male. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation occurred in 83 patients (43%). The most common reason for admission was chemotherapy for primary disease (57%) (Table 1). In total, 157 patients with 345 admissions (71%) had only 1 MRSA nasal swab; 83 patients with 100 admissions (21%) had 2 MRSA nasal swabs; 31 patients with 34 admissions (7%) had 3 MRSA nasal swabs; and 5 patients with 5 admissions (1%) had 4 MRSA nasal swabs.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics

a Unique admissions could have multiple chemotherapy regimens.

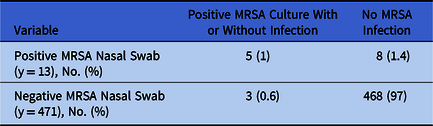

In total, 188 patients with 468 admissions (97%) had a negative MRSA nasal swab upon admission with no culture documented MRSA infection. Also, 3 patients (0.6%) had a negative MRSA nasal swab with a subsequent cultured documented MRSA infection during their admission. Identified infections were bacteremia (n = 2) and confirmed pneumonia (n = 1). Median duration from the first negative MRSA nasal swab to culture documented infection was 16 days (range, 0–87). Moreover, 13 patients (3%) had a positive MRSA nasal swab, of whom 4 had a culture documented MRSA infection and 1 patient met the definition for colonization without active infection (Table 2). Infections included bacteremia (n = 3), confirmed pneumonia (n = 1), and colonization without evidence of infiltrate on chest radiograph (n = 1). MRSA nasal swabs had a sensitivity of 62% (95% CI, 0.24–0.91), and a specificity of 98% (95% CI, 0.96–0.99). Additionally, the PPV was 38% (95% CI, 0.21–0.6) and the NPV was 99% (95% CI, 0.98–1). When comparing the positivity rate between the culture-based nasal swab with the PCR-based nasal swab, the rates were similar in both groups at 2% versus 1.6% (P = 1), respectively.

Table 2. MRSA Nasal Swabs

Note. MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

For each admission, included patients were also assessed for known risk factors of MRSA acquisition: intensive care unit (ICU) admission, mechanical ventilation, admission from an outside facility, and/or initiation of renal replacement therapy.10,Reference Klevens, Morrison and Nadle11 There were 101 patients with 147 ICU admissions (30%), 43 patients with 48 admissions (9%) requiring mechanical ventilation, 36 patients with 38 admissions (8%) were admitted from an outside facility, and 10 patients with 10 admissions (2%) required renal replacement therapy. Although 125 patients with 171 admissions (35%) had 1 or more risk factors for MRSA, the incidence of culture-documented MRSA infections was 3%. None of the patients who had risk factors for MRSA acquisition and a negative initial MRSA nasal swab subsequently developed a positive nasal swab.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the performance characteristics of the MRSA nasal swabs in the AML patient population at high risk for febrile neutropenia. Our findings, derived from 194 patients representing 484 discrete admissions with febrile neutropenia, have revealed that MRSA nasal swab testing has an extremely high NPV in this population.

Confirming NPV in this patient population is important as these patients are often exposed to multiple rounds of antibiotics, and de-escalation is essential in preventing the development of resistant organisms. Furthermore, vancomycin does not decrease time to defervescense, nor does it improve mortality in the setting of negative cultures.Reference Cometta, Kern and De Bock12 Despite this, it can be difficult both to discourage the use of empiric vancomycin therapy and to advocate for timely discontinuation in this population. We recognize the deleterious effects of unnecessarily prolonged vancomycin use, including an increased risk of acute kidney injury as well as the selection for resistant organisms, including vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE). Thus, it is imperative to devise a system to encourage appropriate discontinuation. The MRSA nasal swab in conjunction with microbiologic cultures to identify both MRSA, along with other organisms like Streptococcus spp, Enterococcus spp, and CoNS that would require continuation of anti-MRSA therapy, given their performance characteristics, provide assurance to clinicians that stopping empiric anti-MRSA coverage in febrile neutropenia is safe and enhances antibiotic stewardship efforts.Reference Perreault, McManus and Bar3

Historically, risk factors for hospital-acquired MRSA infection have included ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, admission from an outside facility, and/or initiation of renal replacement therapy.10,Reference Klevens, Morrison and Nadle11 However, in our study, these known risk factors for hospital-acquired MRSA infections did not appear to correlate to our patient population. No patients admitted from a non-home residence and treated in the ICU who required mechanical ventilation and/or renal replacement therapy went on to develop an MRSA infection, nor did these patients have an initial negative MRSA nasal swab with a subsequent positive MRSA nasal swab. Although our standard practice is to repeat swabs if anti-MRSA therapy is reinitiated during the hospital stay and the previous MRSA nasal swab was collected >7 days prior, we identified only 4 patients whose repeat swabs became positive. Therefore, repeat MRSA nasal swabs throughout the hospitalization may not be of benefit.

This study has several limitations. We studied AML patients from a single tertiary-care cancer center; therefore, our results potentially may not be applicable to other cancer patient populations and centers. Although some studies validating NPV of the MRSA nasal swab have had a larger sample, our study is similar in size to others.Reference Schulz, Nonnenmacher and Mutters7,Reference Chan, Dellit and Choudhuri8 The rate of MRSA in this patient population was low at 5%, which may limit applicability to patient populations with a high rate of MRSA colonization or infection. Furthermore, the administration of anti-MRSA therapy was not captured in this study, which could have contributed to false-negative testing and potential differences in baseline characteristics. However, studies have demonstrated that systemic anti-MRSA therapy does not have an effect on colonization, and all patients who are admitted to our institution for febrile neutropenia are started empirically on anti-MRSA therapy.Reference Petersen, Christensen, Zeuthen and Madsen13–Reference Shenoy, Noubary and Kim15 Finally, our testing method for detection of MRSA did change during the study period, which could have had an effect on the overall results. However, the NPV of the MRSA nasal swab has been shown to be similar in multiple studies using both methodologies for testing.Reference Dangerfield, Chung, Webb and Seville4,Reference Chotiprasitsakul, Tamma, Gadala and Cosgrove6 In evaluating our positivity rate for the 2 testing methods, we detected significant differences. These results assure clinicians that MRSA nasal swabs maintain a high NPV and can be used to guide discontinuation of empiric anti-MRSA therapy in the AML patient population.

Acknowledgments

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.