Nosocomial transmission of respiratory viruses can increase morbidity and mortality of inpatients.Reference Chow and Mermel1 Employees may also acquire a respiratory viral illness, with the possible consequence of a sick leave.Reference Edwards, Tomba and de Blasio2

The pertinent national and international guidelines are similar in their recommendations for the prevention of nosocomial respiratory viral illness: The measures are mostly virus-specific and therefore rely on (sometimes expensive) diagnostic methods. Importantly, isolation in a single room is recommended for all patients with suspected and confirmed respiratory tract infections.Reference Siegel, Rhinehart, Jackson and Chiarello3–5 The evidence base for these measures, however, is low. Even in the prevention of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) the only component with documented effectiveness was wearing masks.Reference Seto, Tsang and Yung6

In 2016, our unit assumed oversight of infection prevention for the newly formed Bern University Hospital Group consisting of the university hospital, a large city hospital, and 4 rural hospitals, and we sought to harmonize policies across the sites. No concept for the prevention of nosocomial transmission of respiratory viruses was available in the rural hospitals at that time. This gave us the opportunity to develop a new, pragmatic strategy.

Consequently, we developed the concept of droplet precautions on site (DroPS). The decisive components of this concept are described in Table 1. Another, similar alternative to traditional droplet precautions was recently successfully implemented at a nearby regional hospital.Reference Egger, Mathieu, Boschung, Duppenthaler and Kessler7 To our knowledge, there is no evidence to suggest that such a strategy is equivalent to the currently recommended approach. Therefore, we assessed the healthcare worker (HCW) comprehension, safety, and acceptance of the concept by a survey and analyzed whether the concept increased sick leaves among hospital employees.

Table 1. Description of the Concept “Droplet Precautions on Site”

a Droplet precautions within 1.5 m do not completely exclude potential exposure risk, the risk may still be present within ∼2 m3.

Method

The 4 rural hospitals are all situated in the canton of Bern, Switzerland, within 30 km of the Bern University Hospital, and they all have <200 beds. Most have 2-bed rooms or more, and only few single rooms are available (details in the Supplementary Material online). The DroPS strategy was implemented at all 4 hospitals in week 46 (mid-November) of 2017, following an extensive period of instruction and training.

To evaluate the DroPS strategy, we conducted 2 examinations at the end of the 2017–2018 influenza season: First, a survey was sent to HCWs after the end of the influenza season to measure their understanding of DroPS, their assessment of safety and to gauge their satisfaction (see the Supplementary Materials online for the full survey). The degrees of agreement with each question were recorded using a Likert scale with scores from 1 to 5. The questionnaires were distributed by the senior staff of each hospital to at least 3 nurses and 2 physicians from each ward. The distribution occurred according to the convenience of the senior staff and was not randomized.

We collected participant baseline data on professional background (physician or nurse), employment position (executive vs. non-executive), …, and hospital site, and professional background (physician or nurse). We applied the HH package in R to obtain a descriptive analysis of the Likert scale responses.8 We then used χ2 tests for trend to evaluate differences between responder characteristics and the Likert scale responses transformed into binary variables: For this reason, the responses “strong agreement” and “agreement” were considered positive. Neutral responses, and “disagreement” and “strong disagreement” were considered negative responses.

Second, to evaluate a possible increase in employee absence due to increasing exposure to respiratory viruses at work, we examined the long-term longitudinal overall illness rate before and after the introduction of DroPS. We used the monthly index of sick leave and expected working hours of employees per hospital obtained by the hospital controllers. This index usually shows an increase in the winter months, most likely due to additional infections of the respiratory tract. Indices were visually compared between the rural hospitals and the city university hospital before and after DroPS implementation.

Results

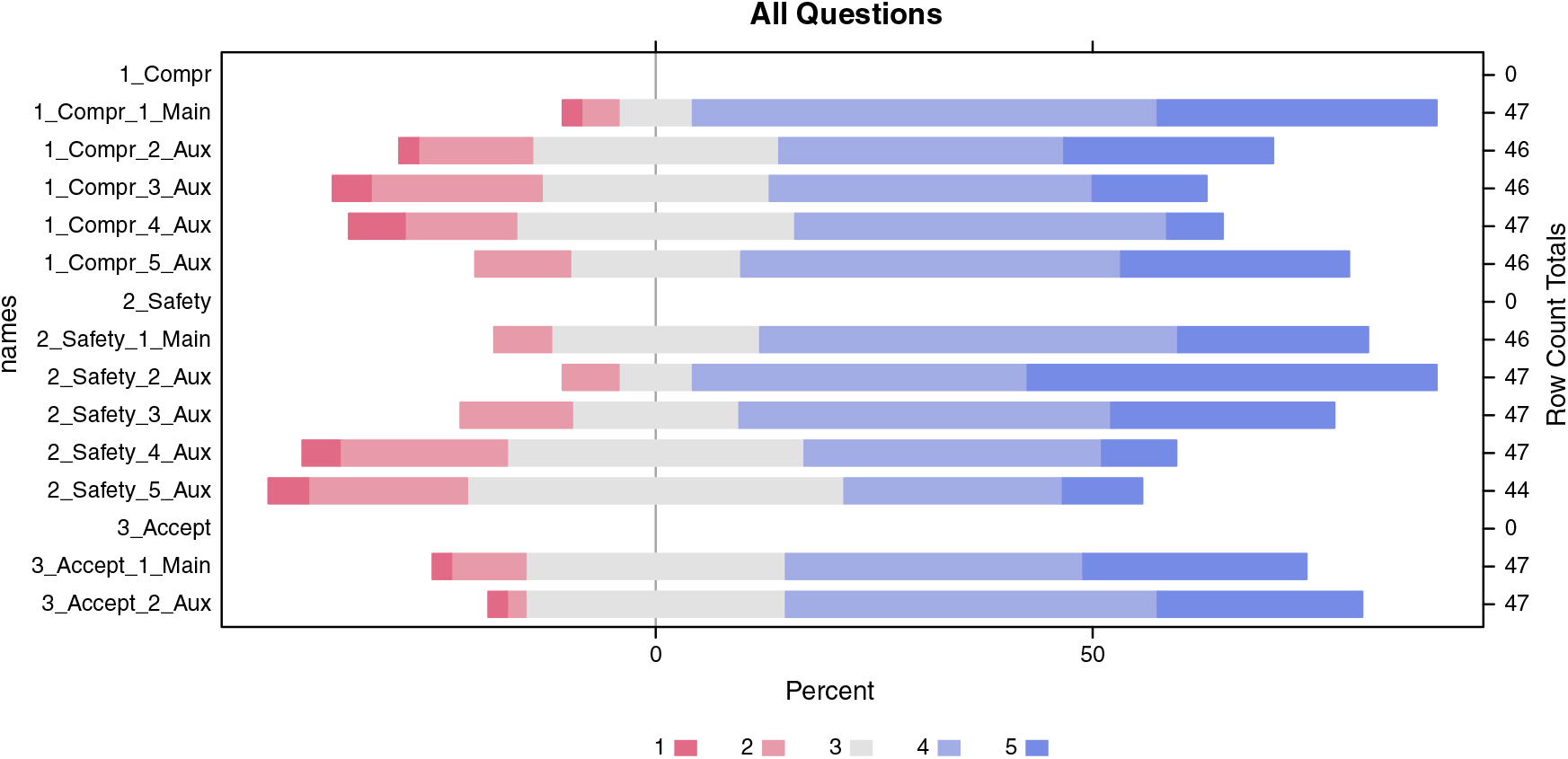

Of the 55 questionnaires sent, 47 were completed (response rate, 85%). Baseline characteristics of the respondents are summarized in the Supplementary Material online. The summary results of the Likert scale responses are shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Likert scale responses. Scale: 1 – strong disagreement; 2 – disagreement; 3 – neutral; 4 – agreement; 5 – strong agreement. The 12 original questions were assigned to 3 main blocks: comprehension, safety, and acceptance. Each block consisted of a main question per block and 2–4 auxiliary questions. The number of valid responses per question is noted on the right y-axis.

Comprehension questions: (1) The concept of droplet precautions on site (DroPS) is intuitive and understandable for me (Compr_1). (2) The process of introduction was sufficient and detailed (Compr_2). (3) I/my team had trouble adapting to the new recommendations (Compr_3). (4) For patients the DroPS concept was clearly understandable (Compr_4). (5) I/my team has independently isolated patients with respiratory symptoms at the bed site (Compr_5).

Safety questions: (1) Nosocomial transmissions have increased after introduction of the DroPS (Safety_1). (2) Wearing masks and hand disinfection were observed while using the DroPS (Safety_2). (3) I feel that I/my colleagues were more frequently infected with respiratory viruses than before (Safety_3). (4) Our patients’ compliance with the DroPS instructions was good (Safety_4). (5) The concept had an additional positive effect on the application of respiratory etiquette to patients/visitors (Safety_5).

Acceptance questions: (1) I would recommend DroPS concept to another hospital of the same size (Accept_1). (2) DroPS is a good replacement for our previous concept (Accept_2).

The questions Safety_3, Compr_3 and Safety_1 were initially asked negatively for quality control purposes and the responses then inverted for the descriptive analysis.

A descriptive analysis of the 3 key questions indicates that 85% of the interviewees understood the concept of DroPS well or very well. Also, 70% of respondents said the new concept was safe or very safe. Finally, 60% indicated their acceptance of the new concept as good or very good. The auxiliary questions provided concordant answers to the main questions (Supplementary Materials online).

In our analysis of dependence of the answers on the characteristics of the respondents, we made several observations between responses from executives and non-executives: executive employees described the process of implementation as more adequate (P = .04); executives rated patient compliance with DroPS instructions as marginally better (P = .05); and they rated the concept of DroPS as more recommendable (P = .04) than did non-executive employees. Also, male responses indicated that they became familiar with the new concept more quickly than women did (P = .02). There were no differences between survey evaluation and the characteristics age group, professional background (physicians vs nursing staff), and individual hospital site (Supplementary Materials online).

In none of the 4 rural hospitals did we note an accentuation of the increase in the sick leave index during the winter months following the introduction of the DroPS concept (Supplementary Material online).

Discussion

We introduced and evaluated a pragmatic modification of traditional droplet precautions for settings without single rooms or with a shortage thereof. The concept was well received by HCWs regarding comprehension, safety, and acceptance. Furthermore, our data suggest that by an indirect marker, there was no increased risk in employee illness after DroPS was introduced. The concept could also be interesting from an economic point of view because patients do not have to be turned away from hospitals using this strategy due to a lack of (isolation) beds. Therefore, we will continue this concept in the rural hospitals in our network in the coming years. An important point, however, is the different response to the survey between executive versus non-executive staff. This finding suggests that the concept may not have been disseminated well enough among the teams or that executive collaborators did not fully understand how difficult implementation was in practice. This discrepancy should be addressed in future evaluations.

The main limitations of this study were lack of data on compliance with the concept during the implementation, surveillance of nosocomially transmitted respiratory infections and/or nosocomial fever, and admission rate of patients with respiratory symptoms. Furthermore, data on the rate of all isolation precautions and hand hygiene compliance before or during the introduction of the concept were missing as well. The strength of the any conclusion based on the questions used here is low because of the small number of participants. This applies in particular to the stratified analysis. Also, the survey cannot be used as a surrogate for measuring the success of the implementation.

More detailed investigations including a prospective trial are necessary to thoroughly compare this concept with the traditional strategy for the prevention of nosocomial respiratory tract infections. In addition, the adequacy of the HCWs’ decision of implementing (or not), and discontinuing (or not) DroPS has to be further assessed (eg, by recording their decision of implementing DroPS in simulated situations).

In the meantime, we cautiously conclude that this pragmatic approach of on-site droplet precautions could be an alternative for all hospitals that lack a prevention strategy for nosocomial respiratory viruses, that do not dispose of single rooms for isolation, or that are experiencing a shortage of single rooms.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2019.142

Author ORCIDs

Rami Sommerstein, 0000-0003-1011-6878; Jonas Marschall, 0000-0002-0052-3210

Acknowledgments

We thank the 4 rural hospitals of the Bern University Hospital Group for pilot testing the DroPS strategy. We thank all participants for answering the questionnaire. In addition we would like to thank Judith Blackburn for providing data regarding the hospital group employees’ sickness index. Finally, we thank Andrew Atkinson for statistical counseling.

Financial support

This work was supported by institutional funding.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.