Acute-care hospitals employ strategies to reduce healthcare associated infections (HAIs) and the spread of resistant organisms. In the most recent nationwide analysis, >90% of acute-care hospitals place patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) on contact precautions. Reference Morgan, Murthy and Munoz-Price1 Although this practice is common and recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America to reduce transmission, contact precautions for endemic MRSA and VRE have become controversial given possible associations with patient harms and reevaluations of the efficacy data. Reference Morgan, Murthy and Munoz-Price1–Reference Morgan, Kaye and Diekema4

Although a large randomized clinical trial has compared contact precautions for MRSA and VRE patients to universal gown and glove use, data directly comparing contact precautions to standard precautions are limited, and no randomized clinical trials have been conducted. Reference Morgan, Murthy and Munoz-Price1,Reference Harris, Pineles and Belton5 Most trials examining the effectiveness of contact precautions have been conducted with a small sample size or included multiple interventions, such as improved hand hygiene, universal decolonization, targeted decolonization for MRSA, and/or active surveillance cultures. Reference Morgan, Murthy and Munoz-Price1 Although combination strategies have demonstrated a decrease in acquisition, colonization, and invasive disease with MRSA and VRE, they do not isolate the effectiveness of gowns and gloves for prevention in endemic settings, and they do not consider locations or conditions in which precautions may not be necessary. Reference Morgan, Murthy and Munoz-Price1,Reference Harris, Pineles and Belton5–Reference De Angelis, Cataldo and De Waure16

Although data are conflicting, several studies have potentially linked contact precautions to patient harms, including decreased contact with healthcare providers, admission or discharge delays, medical chart documentation gaps, hospital onset anxiety and depression, lower satisfaction, and preventable adverse events. Reference Dashiell-Earp, Bell, Ang and Uslan17–Reference Croft, Liquori and Ladd29

Multiple predominantly single-center uncontrolled quasi-experimental studies have shown that contact precautions can be removed with no increase in MRSA and VRE HAI, colonization, and device-associated infections. Reference Martin, Russell and Rubin30–Reference Haessler, Martin and Scales35 One institution also found that noninfectious adverse events declined after contact precautions were discontinued. Reference Martin, Bryant and Grogan36 Although these studies are encouraging, they primarily focus on large, academic hospitals, they lack data from community and smaller hospitals, and they do not fully account for diverse infection prevention practices. Thus, data on hospital conditions and infection prevention practices necessary for successful discontinuation are needed.

In this multihospital study, we aimed to determine the impact of removing contact precautions on the rate of MRSA and VRE HAI, to compare the change in HAI rates in intervention and nonintervention hospitals, and to explore the effect of hospital characteristics and infection prevention practices on the relationship between the discontinuation of contact precautions and MRSA and VRE HAI rates.

Methods

Setting

This study was performed at 15 UPMC inpatient hospitals. UPMC is a health system located predominantly in western and central Pennsylvania that includes tertiary-care hospitals, community hospitals, teaching hospitals, and nonteaching hospitals. The facilities ranged from 40 to 745 beds. Each hospital is guided by system and local infection prevention policies, leading to some variation in infection prevention practice (Table 1). Prior to the study intervention, contact precautions (gown and gloves) were required for contact with any patient with MRSA and/or VRE infection or colonization and/or their environment. Each contact precautions room is equipped with signage, gowns, gloves, alcohol-based hand rub, and sinks. Patients with MRSA or VRE were admitted to private rooms or were cohorted with another patient with identical pathogen status in a semiprivate room. Standard precautions 37 and hand hygiene in accordance with the World Health Organization (WHO) Five Moments 38 were required throughout the study.

Table 1. Hospital Characteristics and Infection Prevention Practices for Intervention and Nonintervention Hospitals

Note. CHG, chlorhexidine gluconate; UV, ultraviolet disinfection device use; ICU, intensive care unit; NICU, neonatal intensive case unit. Intervention hospitals: hospitals that discontinued contact precautions. Non-intervention hospitals: continued contact precautions. CHG bathing all (ie, all patients are bathed with CHG daily), select is use of 1 more of the following CHG bathing strategies: ICU patients, patients with central venous catheters, preoperatively, surgical patients.

a NICUs and burn units did not discontinue contact precautions, regardless of policy change for the rest of the hospital.

Study design

We performed a retrospective, observational, quasi-experimental study comparing the rate of MRSA and VRE HAIs before and after contact precautions were discontinued for endemic MRSA and VRE. The change was a quality improvement initiative approved by the UPMC Quality Review Committee (protocol no. 1670).

UPMC made a policy change recommending removal of contact precautions and patient isolation or cohorting for endemic MRSA and VRE effective February 15, 2018. The preintervention period was from February 1, 2017, to January 31, 2018, and the postintervention period was from March 1, 2018, to February 28, 2019. February 2018 was excluded from the analysis as a wash-in period. Each of the 15 study hospitals independently elected to either to remove contact precautions for MRSA and VRE (intervention hospitals, N = 12) or to continue current practice (nonintervention hospitals, N = 3), based on baseline HAI rates and patient populations at high risk of HAI. All neonatal intensive care units (ICUs) and burn units in intervention hospitals continued precautions for MRSA and VRE.

The primary outcomes were rates of MRSA and VRE HAI per 1,000 patient days and MRSA laboratory-identified (LabID) events per 100 patient admissions using National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) procedures (2017–2019). 39,40 LabID events are based on positive clinical isolates, providing a surrogate marker of HAI. To identify facility-level characteristics that may be associated with the intervention, we compared facility-level conditions among the 12 intervention hospitals with the change in MRSA and VRE HAI rates before and after the intervention. We collected data on hospital characteristics and infection prevention practices from hospital records and local infection prevention teams, including number of beds, percent ICU beds, percent private rooms, chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) bathing, hand hygiene adherence, and use of ultraviolet (UV) disinfection. Hand hygiene adherence was observed independently at each hospital by trained observers before and after the intervention according to the WHO Five Moments of hand hygiene. 38 Compliance data with other infection control practices were not available.

To assess the cost savings of the intervention, we collected data on contact isolation gown purchasing from each intervention hospital before and after the policy change; monthly and overall cost savings were calculated.

Statistical analysis

Aggregate rates were raw sums of HAI and patient days, meaning that larger facilities would contribute more to the rates. Generalized estimating equation models with a Poisson distribution and a log link were used to compare rates before and after the intervention and to calculate difference in differences. Interrupted time series analysis with a Poisson distribution and a log link was used to estimate the level and slope of monthly infection rates prior to the intervention as well as after the intervention. All analyses were performed using Stata/SE version 16.1 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX). A P value <.05 was considered significant.

Results

Study population

Characteristics and infection prevention practices at the 12 intervention and 3 nonintervention hospitals are summarized in Table 1. At the 15 study hospitals, median bed size was 303 (range, 40–745), proportion of private rooms ranged from 5% to 100%, all but one facility performed chlorhexidine bathing in all or some of the patient population. Median hand hygiene adherence was 92% (range, 82%–100%) in the preintervention period and 90% (range, 72%–98%) in the postintervention period. Ultraviolet (UV) disinfection was used for patient rooms in 9 facilities (60%).

MRSA HAI

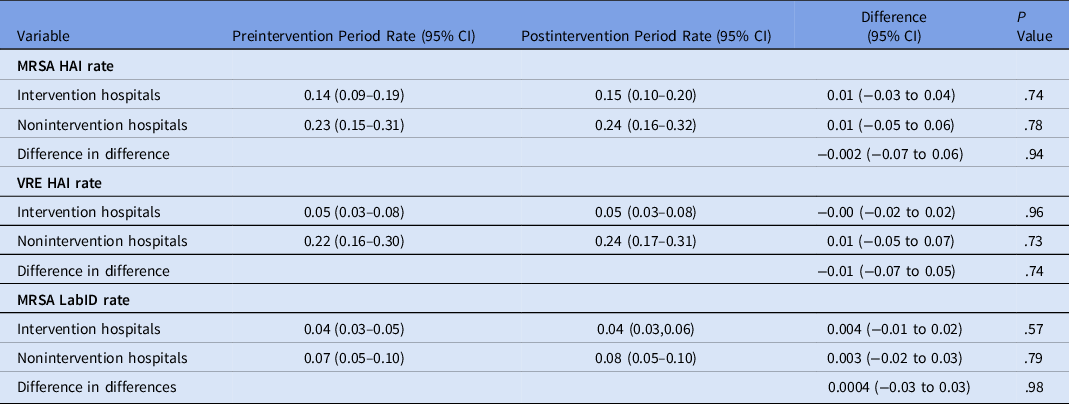

No statistically significant change occurred in the rate of MRSA HAI per 1,000 patient days in the aggregated intervention hospitals 1 year after discontinuing contact precautions (Table 2). No statistically significant change occurred in the MRSA HAI rate at the nonintervention hospitals during the same period. Rates before and after the intervention were compared for the individual 12 intervention hospitals and 3 nonintervention hospitals; none of the changes in hospital-specific rates between the preintervention and postintervention periods were statistically significant (Fig. 1). Although the rate of MRSA HAI was higher at the nonintervention hospitals overall, when comparing rate changes between nonintervention and intervention hospitals, we detected no statically significant difference (P = .74). Neither the immediate change nor slope change was statistically significant for either group (Fig. 2).

Table 2. Generalized Estimating Equation Poisson Models of the Aggregated MRSA and VRE HAI and LabID Event Rates Before and After Discontinuing Continuing Routine Contact Precautions in the Intervention and Nonintervention Hospitals

Note. MRSA, methicillin-resisitant Staphylococcus aureus; VRE, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus; LabID, laboratory identified; CI, confidence interval; HAI, hospital-acquired infection; NHSN, National Health Safety Network; MRSA HAI rate, MRSA healthcare associated infections per NHSN per 1,000 patient days; VRE HAI rate, VRE healthcare associated infections per NHSN per 1,000 patient days; MRSA LabID rate, MRSA LabID events per NHSN per 100 admissions.

Fig. 1. Hospital average monthly MRSA HAI rates, VRE HAI rates, and Lab ID event rates before and after discontinuing continuing routine contact precautions in the intervention and non-intervention hospitals. *P value for change before and after the intervention, 0.021). All other changes in MRSA HAI, VRE HAI, and MRSA lab ID event rates were not statistically significant. Note. MRSA, methicillin-resisitant Staphylococcus aureus; VRE, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus; LabID, laboratory identified; HAI, hospital-acquired infection; NHSN, National Health Safety Network; MRSA HAI rate = MRSA healthcare associated infections per NHSN per 1,000 patient days; VRE HAI rate = VRE healthcare associated infections per NHSN per 1,000 patient days; MRSA lab ID rate = MRSA lab ID events per NHSN per 100 admissions. Absent bars indicate a rate of zero for that period.

Fig. 2. Aggregated monthly MRSA HAI rates, VRE HAI rates, and LabID event rates before and after discontinuing continuing routine contact precautions in the intervention and non-intervention hospitals. Note. Intervention hospitals: discontinued contact precautions on February 15, 2018, includes aggregated data from hospitals A–L. Nonintervention hospitals: continued contact precautions in the pre and post period, includes aggregated data from hospitals M–O. Note. MRSA, methicillin-resisitant Staphylococcus aureus; VRE, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus; LabID, laboratory identified; HAI, hospital-acquired infection; NHSN, National Health Safety Network; MRSA HAI rate = MRSA healthcare associated infections per NHSN per 1,000 patient days; VRE HAI rate = VRE healthcare associated infections per NHSN per 1,000 patient days; MRSA lab ID rate = MRSA lab ID events per NHSN per 100 admissions.

VRE HAI

The aggregated rates of VRE HAI per 1,000 patient days for the intervention hospitals and nonintervention hospitals were unchanged after discontinuing routine contact precautions (Table 2). The rate of VRE HAI was higher in the nonintervention hospitals than the intervention hospitals in both the preintervention and postintervention periods, but the VRE HAI rate did not change appreciably for any hospitals in either group (Fig. 1). The immediate change and the slope change were also assessed for both intervention and nonintervention hospitals and neither was statistically significant (Fig. 2). Among the intervention hospitals, 4 (D, H, J, L) had no VRE HAI in the postintervention period.

MRSA LabID events

No statistically significant increases in the MRSA LabID events rates per 100 admissions occurred in either the aggregated intervention or the nonintervention hospitals (Table 2). Neither the immediate change nor the slope change was statistically significant (Fig. 2). However, a statistically significant increase in the hospital B rate occurred after contact precautions were discontinued: preintervention rate, 0.046; postintervention rate, 0.106 (P = .021). The changes between the rate in the preintervention and postintervention periods in the remaining hospitals were not statistically significant (Fig. 1).

Association between change in HAI and facility-level conditions

We detected no associations with (1) status as a community or a tertiary-care facility, (2) bed size, (3) percentage ICU population, or (4) the change in rates of MRSA or VRE HAI per 1,000 patient days (Fig. 3). There was no association between the hospital’s percentage of private rooms and the change in the rate of VRE HAI per 1,000 patient days, although there was an increase in MRSA HAI per 1,000 patient days in hospitals with a higher percentage of private rooms (ρ, 0.659; P = .04). There was no association between the use of CHG bathing and change in rate of MRSA or VRE HAI after removing contact precautions. Whether a hospital used 1 or more CHG bathing strategy or universal CHG bathing was not correlated with the change in rate after precautions were discontinued (data not shown). Additionally, there were no correlations between hand hygiene compliance or UV disinfection and rates of MRSA and VRE HAI after precautions were removed. Each of these factors was also assessed for correlation with the change in MRSA LabID event rate per 100 admissions, and no significant correlations were detected (data not shown).

Fig. 3. Association between select hospital and infection prevention factors and the change in MRSA and VRE HAI rates in the pre- and post-intervention periods among the 12 intervention hospitals. Note. MRSA, methicillin-resisitant Staphylococcus aureus; VRE, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus; HAI, healthcare-associated infection; CHG, chlorhexidine gluconate; HH, hand hygiene; UV, ultraviolet light disinfection; ICU, intensive care unit.

Cost analysis

Cost data were available for 11 of the 12 intervention hospitals (hospital C data were unavailable). The total cost for PPE in these 11 hospitals was $643,861.90 in the 12 months before the intervention and $290,441.60 in the 1 year after contact precautions were discontinued for MRSA and VRE. This intervention led to a 1-year savings of $353,420.30 and an average monthly savings of $29,451.69.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that contact precautions for MRSA and VRE could be safely removed from these 12 diverse intervention hospitals with low baseline HAI rates and good hand hygiene compliance with no increase in observed HAI rates. After contact precautions were discontinued, aggregated MRSA HAI went from 0.14 and 0.15 per 1,000 patient days, VRE HAI remained 0.05 per 1,000 patient days, and MRSA LabID events remained 0.04 per 100 admissions. We detected no significant differences when we compared rate changes between intervention and nonintervention hospitals. One hospital had a significant increase in MRSA LabID events, which is considered a surrogate marker of HAI, but there was no corresponding increase in MRSA HAI in that hospital. This study expands on the published experience of discontinuing routine MRSA and VRE contact precautions by including a more diverse set of hospitals and by investigating hospital characteristics and infection prevention practices that may predict safely discontinuing contact precautions in non-outbreak settings. Discontinuation was successful in both large tertiary hospitals and smaller community hospitals, among which infection prevention practices varied. All successful hospitals had low baseline rates of MRSA and VRE HAI, and high hand-hygiene adherence, suggesting that these factors may also be important in successful discontinuation.

Multiple nonrandomized, single-center, before-and-after studies have shown that contact precautions can be removed with no increase in MRSA and VRE HAI, colonization, or device-associated infections. Reference Martin, Russell and Rubin30–Reference Haessler, Martin and Scales35 Although these data are encouraging, they are primarily from large, academic institutions that have strong horizontal infection prevention practices and/or universal private rooms but lack information from a wider range of hospitals. This study confirms that contact precautions can be successfully discontinued, and these results provide multiple additional insights that further the literature on the safety of discontinuing contact precautions. First, to our knowledge, with 12 intervention hospitals, this is the largest study to date on the impact of discounting routine contact precautions. Second, we offer a wider diversity of hospitals, including smaller, community facilities that better represent the large variety of US hospitals. Our study also included 3 nonintervention hospitals with similar geography and organizational practices that continued contact precautions, serving as a comparator population.

Data on factors necessary for the discontinuation of contact precautions for MRSA and VRE to be successful are limited. Prior studies on the impact of discontinuing routine contact precautions have found no increased in MRSA or VRE HAIs with the inclusion of universal CHG bathing, private rooms, and/or adoption of other horizonal infection prevention strategies. It has been unclear which, if any, of these factors are necessary for success. Reference Martin, Russell and Rubin30–Reference Haessler, Martin and Scales35 In this study, we not only looked at the impact of removing precautions, we also examined the possible relationship between multiple hospital and infection prevention factors on the change in rates of MRSA and VRE HAI after contact precautions were discontinued. There were no correlations between the change in rates and most factors assessed, including hospital size, percentage ICU population, CHG bathing, UV disinfection, hand hygiene adherence, or community versus tertiary hospital status. Although we did not identify specific factors that predict failure, we can postulate several factors that are likely to predict success and other factors that may not be required. First, hand hygiene adherence was high in all hospitals that successfully removed precautions, and this is likely essential for success. Second, each intervention hospital had low baseline rates of both hospital-associated MRSA and VRE. Although we do not have data on removal in hospitals with high rates, low baseline rates of MRSA and VRE HAI are likely an important factor in successful discontinuation. Third, our study did not find a correlation between hospital size or community or tertiary status, indicating that size and hospital make-up are not essential factors. Thus, a wide variety of hospitals may be successful if the other infection prevention factors are in place. Finally, these results suggest that hospitals with a higher proportion of double/multioccupancy rooms may be more successful after discontinuing contact precautions than facilities with more private rooms. These findings do not necessarily mean that single-occupancy rooms are correlated with a poor outcome, especially given prior studies that have successfully removed precautions in facilities with universal private rooms. Instead, facilities with multioccupancy rooms can be successful if the burden of MRSA and VRE are low and adherence to horizontal infection prevention strategies is high.

This study had several limitations. Although this study had an interrupted time series design with control hospitals, it was still observational, and assignment to either an intervention or control group was based on self-selection, not random assignment. The nonintervention hospitals provide some control given system infection prevention policies, but the hospitals that chose not to change policy had significantly higher rates of MRSA and VRE HAI, which is not likely an optimal condition for removing precautions. Although this was a large study of the discontinuation of contact precautions, we only included data from 12 hospitals with 1 year of follow-up. These data support several conditions where discontinuing precautions may be successful; however, they are not substantial enough to model degrees and permutations of hospital and infection prevention factors, such as hand hygiene adherence or baseline MRSA/VRE transmission. Although all study hospitals used WHO Five Moments 38 for hand hygiene, each hospital was responsible for their data, and there was no formal process to ensure validity across the system. Data regarding compliance with infection prevention factors other than hand hygiene were not available, and poor compliance with those infection prevention practices could have skewed the data. Although room cleaning is also likely influential, we only assessed UV disinfection primarily at time of patient discharge and not the quality of daily and postdischarge room cleaning. This study used a surveillance, rather than clinical, definition of the study outcome. Although NHSN definitions are widely used in acute-care hospitals, cases may have been included that were not true infections and other true infections may have been missed because they did not meet these strict definitions. We also considered HAI, which is an important patient outcome, but this may not fully represent transmission because a method of genetic typing was not included. Finally, this study only controlled for the factors listed and may not have accounted for other hospital factors that affected rates.

Our results suggest that contact precautions for endemic MRSA and VRE can be safely removed under the right conditions without increasing HAI in a large, diverse health system, which would lead to significant cost savings on isolation gowns. The exact conditions necessary require further investigation, but this study supports the importance of high rates of hand hygiene and low rates of HAI with MRSA and VRE. Further data on the necessary thresholds would be helpful, and we would not recommend discontinuation at this time in settings with poor hand hygiene or high HAI rates. Additionally, we did not address a potential strategy of targeted precautions, for example, at the unit-level within a hospital, as a strategy to more efficiently use this prevention measure. Because some populations will likely benefit from contact precautions, further data on how to target these populations and how to mitigate the potential harms of contact precautions should be evaluated in future research.

Acknowledgments

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.