Surgical site infections (SSIs) occur at the surgical incision site or in the related fascia, muscle, or organ-space areas following a surgery.Reference Won, Wong and Mayhall1 They are a common healthcare-associated infection and cause substantial morbidity, increased costs, prolonged hospitalization, and in some cases, patient death.2–Reference Rennert-May, Conly and Smith4

To understand the burden and distribution, and to establish comparable rates for benchmarking of SSIs in a particular healthcare system, an SSI monitoring system is recommended.Reference Berríos-Torres, Umscheid and Bratzler3 This monitoring system can be a focused investigation of infection for all patients who have a particular surgery or a broad investigation of infection following several surgeries among a selected number of patients.

Currently, the province of Alberta, Canada, uses 2 approaches to monitor SSIs following total hip replacement (THR) and total knee replacement (TKR) surgeries. A focused approach is used by the infection prevention and control program (IPC) of Alberta Health Services (AHS)5 in partnership with the Alberta Bone and Joint Health Institute (ABJHI) at all sites in Alberta where these surgeries are performed. A broader approach to monitoring SSIs is used by the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP).6

The NSQIP6 originated in the United States to improve the surgical care of veterans. In 2004, they began enrolling additional private-sector hospitals into the program. This program was the first to provide nationally validated, risk-adjusted, outcomes-based measures to improve the quality of surgical care in the United States. Starting in 2015, the NSQIP began collecting data on multiple surgeries, including THRs and TKRs at 4 hospital sites in Alberta, Canada. The program expanded to 14 sites in 2018. Since both IPC and NSQIP report SSI rates, it is vital to understand the degree to which data collection methods may be affecting reported SSI rates, especially since quality improvement (QI) initiatives may be implemented based on the findings and differences in SSI reporting have been reported for other surgeries.Reference Bordeianou, Cauley and Antonelli7–Reference Taylor, Marten and Potts11

In this study, we aimed (1) to determine whether the focused approach used by IPC and the broader approach used by NSQIP within Alberta demonstrated similar results and similar trends over time in THR and TKR SSI reporting and (2) to conduct deterministic matching of patient data from both approaches to examine the overlap and discrepancies in SSI reporting.

Methods

Alberta Health Services (AHS), and its contracted partner Covenant Health, provide all acute care in hospitals within the province of Alberta, Canada. A provincial IPC program provides coverage at every acute-care hospital with a robust centralized IPC surveillance system that uses a web-based data entry platform so that each patient is counted only once. NSQIP operates at select acute-care hospitals with data uploaded to a web-based data entry platform.

Cohort description

In this multisite retrospective cohort study, we compared 2 SSI data collection methods used to report postoperative SSI rates following primary, clean, elective THRs, and TKRs: (1) the IPC Program working in concert with the ABJHI and (2) NSQIP. The first 4 hospitals in Alberta, Canada, that started NSQIP surveillance and collected data using both methods were included. The hospitals were labelled 1–4 based on case volume, with ˜100, 50, 50, and 35 surgeries per month, respectively. All patients who had a THR or TKR between September 1, 2015, and March 31, 2018, were eligible for inclusion. Patients were excluded if they returned to the operating room for a revision of a previous prosthetic component(s) within the joint; if the patient died within 24 hours of the surgery; if surgery was emergent; or if surgery was classified as dirty (ie, included old traumatic wounds with retained devitalized tissue or existing clinical infection).12

IPC surveillance program

IPC in collaboration with the ABJHI performs population-based surveillance for SSIs on all THRs or TKRs performed in Alberta acute-care facilities (13 facilities).5 Between September 1, 2015, and March 31, 2017, infections were captured during the 6 months following the surgery date. Beginning April 1, 2017, this follow-up period was limited to 90 days. IPC case finding at the site included laboratory records and/or chart review5 and was supplemented with a standardized, provincial, case-finding process in which administrative data were reviewed for patients who were readmitted following surgery.Reference Rusk, Bush and Brandt13 Infections were classified as deep or organ-space according to the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN)2 definitions (Table 1 and Supplementary Material online).

Table 1. Characteristics of Patients With Total Hip Replacements (THRs) and Total Knee Replacements (TKRs), September 2015–March 2018

Note. IPC, Infection Prevention and Control program; NSQIP: National Surgical Quality Improvement Program.

a Significant difference as compared to NSQIP (P < .05).

b Complex infections include surgical site infections classified as deep or organ-space.

c Prior to April 2017, complex infections were followed by IPC for 6 months.

NSQIP surveillance program

NSQIP uses a systematic sampling protocol to determine which surgeries are sampled. Certified surgical clinical reviewers are responsible for assigning common procedure type (CPT) codes to the primary NSQIP abstracted procedure.6,Reference Ju, Ko, Hall, Bosk, Bilimoria and Wick8 The primary procedure is the most complicated of all procedures performed during the patient’s surgery and is considered the primary focus of assessment. Reviewers capture prospective data on >150 variables, including 30-day postoperative mortality and morbidity outcomes (eg, infections) according to a nationally standardized protocol that includes medical chart abstraction.Reference Khuri14,Reference Shiloach, Frencher and Steeger15 Infections were classified as superficial, deep, or organ-space according to the NSQIP user guide; however, superficial infections were excluded from the analysis. All outcome variables were risk and case-mix adjusted to allow for accurate national benchmarking. The CPT codes that were abstracted for this study were T27130 for THRs and T27447 for TKRs. These codes do not include revisions or complications, hemiarthroplasties, or any emergent or trauma-related arthroplasties because these have other CPT codes (see Table 1 and Supplementary Material online).

Ethics

A project ethics community consensus initiative screening ethics tool deemed this project to be a quality improvement effort; therefore, ethics certification was waived.

Database comparison

Data provided by IPC included date of birth, gender, surgery type (THR or TKR), surgery side, surgery date, incision start time, incision closure time, surgery facility, and SSI type (ie, superficial incisional, deep incisional, organ-space), and infection date. NSQIP data included year of birth, gender, CPT code (27130 or 27447), CPT description, principal operative procedure, operation date, surgery start, surgery end, SSI type (postoperative superficial incisional, postoperative deep incisional, or postoperative organ-space).

Records with missing information were removed from the NSQIP database and duplicate records were excluded from both databases if birth year, gender, facility code, surgery type, surgery side, and surgery date were identical. Demographic information, including median age, gender and bed size were analyzed for each hospital and both THRs and TKRs. Complex SSIs (ie, deep, and organ-space SSIs) that occurred within 30 and 90 days for IPC and within 30 days for NSQIP were identified. Because identifiable data were not available from NSQIP, deterministic matching between databases was done using surgery facility, surgery type/side, surgery date, surgery time, and patient year of birth. In the matched cohort, total SSIs and complex SSIs that occurred within 30 days of the surgery were identified.

Statistical analysis

Data gathered by IPC and NSQIP were compared prior to and after linkage. Descriptive epidemiologic statistics were reported as percentages for categorical variables. Univariate analyses using the Mood median test for age and the χ2 test without correction for sex, complex SSIs, and total SSIs were performed. The Pearson correlation and the Shapiro-Wilk test were used to assess THR and TKR trends between the 2 data sources. Percent agreement and the Cohen κ were obtained to compare concordance in the matched database.Reference McHugh16 The following scoring system was utilized: 0–0.2 = no agreement; 0.21–0.39 = minimal agreement; 0.40–0.59 = weak agreement; 0.60–0.79 = moderate agreement; 0.80–0.90 = strong agreement; and >0.90 = almost perfect agreement. Statistical tests were 2-sided, and P values < .05 were considered significant. This analysis was performed using Stata 15 version 15 statistical software (2017, StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Study cohort

Among the 4 hospitals, there were 7,549 THRs and TKRs in the IPC data after the removal of 86 duplicate records (1.13%). In the NSQIP data, there were 2,037 THR and TKRs after the removal of records with missing data, unknown side code, indications of hemiarthroplasty and duplicate records (n = 52) (see Supplementary Information, Table 2).

Table 2. Characteristics of Patients in the Matched Cohort With THRs and TKRs, September 2015–March 2018

Note. THR, total hip replacement; TKR, total knee replacement; IPC, Infection Prevention and Control program; NSQIP, National Surgical Quality Improvement Program.

a These are infections that both IPC and NSQIP agree are cases.

Demographic characteristics

Demographic characteristics from all 4 sites for both IPC and NSQIP were compared (Table 1). For THRs, the median age was 66 years of age (interquartile range [IQR], 58–74), and 46.9% were male in the IPC data, and the median age was 67 years (IQR, 59–75) and 45.8% were male in the NSQIP data (P = .180 and .582). For TKRs, median age was 67 years of age (IQR, 61–73) and 40.5% were male in the IPC data, and the median age was 67 years (IQR, 61–73) and 42.6% were male in the NSQIP data (P = 0.997 and 0.208).

Total hip replacement SSIs

The 30-day THR complex SSI rate reported by NSQIP was higher than the 90-day THR complex SSI rate reported by IPC, but the difference did not reach significance (1.19 vs 0.68; P = .147).

Although IPC follows cases for 90 days, to allow for a more comparable analysis, cases identified between 31 and 90 days were excluded from the IPC database and SSI rates were further analyzed. The 30-day THR complex SSI rate reported by NSQIP was significantly higher than the 30-day THR complex SSI rate reported by IPC (1.19 vs 0.55; P < .05).

Total knee replacement SSIs

The 30-day TKR complex SSI rate reported by NSQIP was higher than the 90-day TKR complex SSI rate reported by IPC, but the difference did not reach significance (0.92 vs 0.80; P = .682). After excluding infections reported by IPC between 31 and 90 days, the 30-day TKR complex SSI rate reported by NSQIP was significantly higher than the 30-day TKR complex SSI rate reported by IPC (0.92 vs 0.30; P < .05). The overall THR and TKR complex SSI rates for NSQIP at 30 days and for IPC at 90 days were also compared over time using semiannual rates. Different rates and, importantly, different trends were reported by each approach; however, the different rates and trends were more evident for TKRs (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Semiannual THR and TKR complex SSI rate (September 2015–March 2018). Note. THR, total hip replacement; TKR, total knee replacement; SSI, surgical site infection; NSQIP, National Surgical Quality Improvement Program; IPC, infection prevention and control.

Matched cohort

Of the 7,549 surgeries captured by the IPC program and the 2,037 surgeries captured by the NSQIP programs, 1,798 (23.8%) were matched to both programs with no differences in sex or age distribution in the matched database (Table 2). The matched complex SSI rate for THR and TKR combined was significantly lower than the rate reported by NSQIP prior to matching (0.39% vs 1.03%; P < .05), but it was not significantly different than the rate reported by IPC at 90 or 30 days prior to matching (0.39% vs 0.76% [P = .091] and 0.39% vs 0.40% [P = .960], respectively). For those surgeries that matched between both methods, Table 3 shows the matching for identifying all complex SSIs (agreement: weak, κ = 0.48; positive agreement, 0.48; negative agreement, 1.00).

Table 3. SSI Within 30 Days

Note. THR, total hip replacement; TKR, total knee replacement; IPC, infection prevention and Control program; ABJHI, Alberta Bone and Joint Health Institute; NSQIP, National Surgical Quality Improvement Program; SSI, surgical site infection.

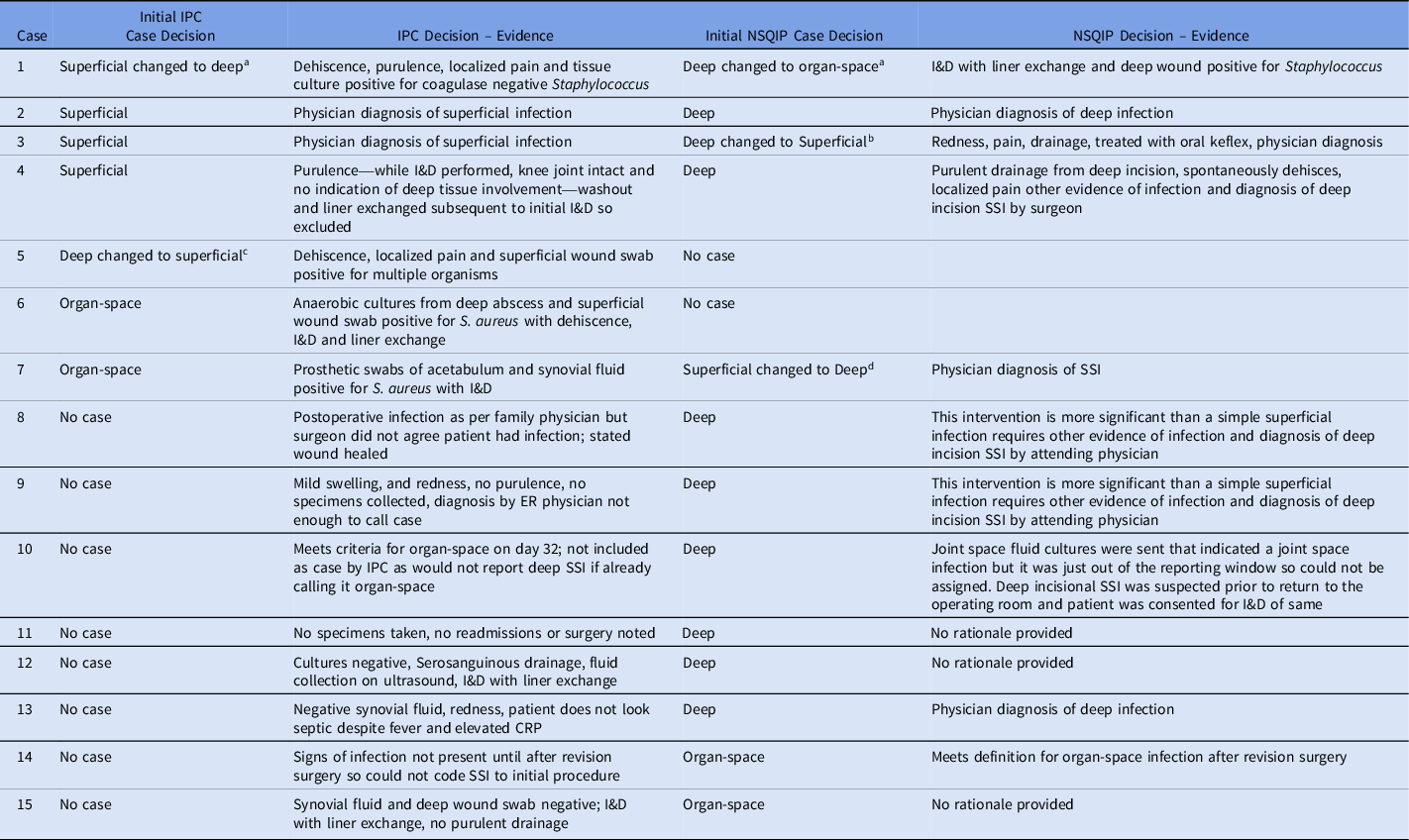

Adjudication of the 15 cases that were not considered a complex SSI by both IPC and NSQIP resulted in agreement by IPC and NSQIP that 2 cases were complex SSIs and 1 case was a superficial SSI. The remaining cases could not be resolved, and 10 cases (67%) were completely discordant, with NSQIP most frequently calling them deep SSIs and IPC calling them noncases. A detailed explanation of the definitions used to meet infection is provided in Table 4.

Table 4. Case Decisions for Complex Surgical Site Infections: Variations in Evidence

Note. IPC, Infection Prevention and Control program; I&D, irrigation and debridement; NSQIP, National Surgical Quality Improvement Program; SSI, surgical site infection; ER, emergency room; CRP, C-reactive protein.

a On re-review, IPC changed case decision to deep and NSQIP changed case decision to organ-space.

b On re-review, NSQIP changed case decision to superficial.

c On re-review, IPC changed case decision to superficial.

d On re-review NSQIP changed case decision to deep.

Discussion

Having an accurate and reliable surveillance system for benchmarking postoperative infections is critical to supporting QI activities and QI uptake at the local level. However, determining whether surveillance systems are providing accurate information can be difficult, and accuracy is only one element of information quality. The Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) uses 5 dimensions17 to describe and assess information quality: (1) accuracy and/or reliability, (2) relevance, (3) timeliness and/or punctuality, (4) accessibility and/or clarity, and (5) comparability and/or coherence. These dimensions need to be balanced because improvements to one may lead to deficiencies in another.

In this study, we sought to understand the quality of information from 2 methods of data collection (ie, IPC and NSQIP) in a provincial health system that is performing surveillance for SSIs following THRs and TKRs. The analysis identified numerous discordances in rates reported between IPC and NSQIP, including higher rates of complex SSIs reported by NSQIP, and different semiannual rate trends reported over time for both TKRs and THRs. Agreement was weak when a cohort of similar patients was compared between the 2 methods. In addition, the 2 methods often reported different SSI severities for the same patient in this matched cohort. These differences in SSI rates between NHSN and NSQIP were previously documented following colonReference Bordeianou, Cauley and Antonelli7–Reference Childers, Usiak and Sovel10 and gynecologic surgeries.Reference Taylor, Marten and Potts11 To our knowledge, this is the first analysis comparing NSQIP data with comprehensive, nonadministrative data sources for orthopedic surgeries and the first report of such comparisons outside the United States. Previous correlations of orthopedic surgeriesReference Bohl, Basques, Golinvaux, Baumgaertner and Grauer18–Reference Pierce, Menendez, Tybor and Salzler20 have compared NSQIP with administrative databases, such as the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), the Humana Administrative Claims Databases, and the National Hospital Discharge Survey, which lack postdischarge follow-up of cases that was included in IPC postdischarge surveillance.

Higher rates of complex SSIs were reported by NSQIP than by IPC for both THRs and TKRs as well as when the 2 procedures were combined (1.03 vs 0.76 [P = .219] vs 1.13 [P < .05]). This difference reached significance when the follow-up time was restricted to 30 days for IPC (1.03 vs 0.40; P < .05). Although the rates were not significantly different overall, we observed differences in the semiannual trends, which is very important to hospital QI programs which may invest considerable resources based on trending data. Relying on a rate by one system in one time period and another system in another time period could lead to different recommendations.

Other studies have also reported higher NSQIP rates,Reference Bordeianou, Cauley and Antonelli7,Reference Bohl, Basques, Golinvaux, Baumgaertner and Grauer18,Reference Aiello, Shue and Kini21 perhaps due to a different postsurgical follow-up process. Within our health system, infection control professionals do not often make direct contact with the patient, but there is an additional standardized case finding process that uses administrative data to identify potential SSIsReference Rusk, Bush and Brandt13 plus access to qualified IPC physicians for difficult cases. This case finding occurs is in addition to the steps that these professionals are already using to identify cases.5 Reasons other than case finding methodologies can be implicated in this discordance. Ali-Mucheru et alReference Ali-Mucheru, Seville, Miller, Sampathkumar and Etzioni22 indicated 3 reasons for potential discordance: imperfect criteria, differences in scope, and incomplete sensitivity. The ability to review outpatient charts or detect readmission for infection at a facility other than the operative may also lead to discordant results. Whatever the reason for the discordance, it is imperative that stakeholders are made aware of these differences so that results can be interpreted in the context of the methods used for case finding.

In addition to looking at overall rates, a matched cohort of similar patients followed by both systems was also investigated. We were unable to find other studies that evaluted matching data for orthopedic surgeries, although similar studies have been done for all surgeries,Reference Ali-Mucheru, Seville, Miller, Sampathkumar and Etzioni22,Reference Etzioni, Lessow and Lucas23 including colon surgeries,Reference Bordeianou, Cauley and Antonelli7,Reference Gase, Kelly, Hohrein, Siebels and Babcock9 gynecological surgeries,Reference Taylor, Marten and Potts11 and vascular surgeries.Reference Aiello, Shue and Kini21 Similar to these reported studies, and to the prematching data in our study, the matched SSI rate for THR and TKR SSIs was significantly lower than that reported by NSQIP (0.39 vs 1.03 per 100 surgeries; p < .05) but not significantly different than that reported by IPC (0.39 vs 0.76; P = .09), further suggesting that the databases are not comparable.

A major strength of our study is that it included hospitals with varying case volumes and complexity, which allowed us to compare different types of hospitals, and SSI rates were more variable when fewer surgeries were performed (hospital 4). In addition, IPC carries out very comprehensive case finding using a standardized approach with a robust data quality process as a part of case finding. To our knowledge, this is the first Canadian study to examine the comparability of NSQIP to nonadministrative SSI surveillance. We also evaluated data from both methods using a matched cohort to assess trend differences, which is an important element with respect to quality improvement initiatives.

This study has several limitations. First, we investigated a relatively small sample of hospitals. The 2 largest hospitals performing elective orthopedic surgeries in the provincial network were not represented, and only one-quarter of the total hospitals were sampled. A larger and more diverse sample of hospitals, including academic hospitals and hospitals outside our provincial network, would have increased the power for us to detect differences between the 2 systems and would have improved our external validity. However, as NSQIP was not in operation at the larger provincial hospitals at the time of this study, so this investigation was not possible.

Second, an exact case match could not be performed because different coding mechanisms were used by the 2 methods to identify the population who had the surgery. The ABJHI identifies those patients receiving a THR or TKR and provides this information to IPC, using International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) Canadian edition, whereas NSQIP identifies the patients with a THR or TKR using current procedural terminology (CPT) codes. As a result, 239 (12%) of 2,037 NSQIP cases did not match the IPC database. Because age and sex proportion were similar in both cohorts prior to and after matching, and an additional check of surgery facility, date, and time identified very few mismatches, we are confident that the cases were properly matched.

Third, because THRs and TKRs are the only orthopedic surgeries that are followed provincially by IPC, these selected surgeries were compared between the 2 systems. Results presented here only reflect a subset of all orthopedic surgeries that are performed and focus on complex SSIs as the main outcome of interest. Superficial SSIs were excluded from the analysis because the diagnosis of superficial SSIs is often inconsistent, prone to error, and subjective.Reference Ming, Chen, Miller, Sexton and Anderson24 In addition, NSQIP follows many postoperative morbidity and mortality outcomes, of which SSI rates are only one. This finding suggests that the SSI results may not be generalizable, although based on literature from other types of surgeries,Reference Bordeianou, Cauley and Antonelli7,Reference Gase, Kelly, Hohrein, Siebels and Babcock9,Reference Taylor, Marten and Potts11,Reference Aiello, Shue and Kini21,Reference Bohl, Russo and Basques25 this seems unlikely.

Different approaches can be used to monitor SSIs following surgery and these approaches can lead to different results. The results reported by IPC and NSQIP are not comparable. Both surveillance systems are critically involved with improving patient outcomes following surgery. However, stakeholders need to be aware of these variations and education should be provided to clinicians to support an understanding of the differences and their interpretation to focus and guide major resource allocations for QI initiatives aimed at rising infection rates. Future work should explore other surgeries and larger databases.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2021.159

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contribution of the infection control professionals and IPC physicians at the acute care sites in AHS and Covenant Health; the orthopedic surgeons in the province, who submit patient information to ABJHI for surveillance; and members of the IPC Surveillance and Standards, Analytics, NSQIP and ABJHI teams for their work in data cleaning and extraction.

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.