In the United States, approximately 1.4 million people reside in more than 15,700 community-based nursing homes.Reference Harris-Kojetin, Sengupta, Park-Lee and Valverde 1 The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) nursing homes, also referred to as Community Living Centers, serve nearly 50,000 Veterans each year. Nursing homes are crucial for meeting the post-acute and long-term care needs of older adults. With the burgeoning post-acute care population, many of these individuals are recovering from serious events and are at high risk of complications, including infections, leading to substantial morbidity and mortality.Reference Jones, Dwyer, Bercovitz and Strahan 2 , 3 Urinary tract infection (UTI) is the most commonly reported infection, although this may be due in part to overtreatment and misclassification of asymptomatic bacteriuria as an infection.Reference Peron, Hirsch, July, Jump and Donskey 4

To reduce the incidence of infections, nursing homes must have individualized infection control programs.Reference Collier and Collier 5 , Reference Ye, Mukamel, Huang, Li and Temkin-Greener 6 Furthermore, in 2013, the US Department of Health and Human Services approved a plan to enhance nursing home resident safety by reducing healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), with particular emphasis on reducing indwelling urinary catheter use and catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI). 7 However, unlike infection preventionists working in acute care hospitals, infection preventionists in nursing homes commonly have responsibilities other than infection control, such as employee health or staff education, and many receive no formal training in infection prevention.Reference Herzig, Stone and Castle 8

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Safety Program for Long-term Care: HAIs/CAUTIReference Mody, Meddings and Edson 9 aims to reduce CAUTIs, to enhance frontline healthcare professional knowledge about infection prevention, and to improve the safety culture in nursing homes. This national collaborative builds on an AHRQ-funded national project in acute care hospitals (ie, the AHRQ Safety Program to Reduce Catheter-Associated UTI in Hospitals)Reference Saint, Greene and Krein 10 by expanding to the long-term care setting.Reference Mody, Krein and Saint 11 Both VA and non-VA nursing homes participated in the national collaborative. Participating nursing homes were asked to complete a needs assessment questionnaire designed to assess the general characteristics of the facility, as well as the structure and process of their infection prevention program, including strengths and gaps related to CAUTI prevention. We hypothesized that VA nursing homes would have a more robust infection prevention infrastructure and better CAUTI surveillance practices due to the centralized organizational structure of the VA healthcare system and the fact that many VA nursing homes are colocated with acute care medical centers.

METHODS

Study Design

Between January 2014 and June 2015, at the start of each cohort of nursing homes participating in the AHRQ Safety Program for Long-term Care: HAIs/CAUTI collaborative,Reference Mody, Meddings and Edson 9 a needs assessment questionnaire was sent by e-mail to the organizational leaders responsible for managing project activities among a group of nursing home facilities. The needs assessment questionnaire was made available to participating facilities (63 VA and 431 non-VA facilities) electronically by weblink or by paper. Team leaders were asked to complete the online or hard-copy questionnaire within 1 month; reminders were included in weekly newsletters. The national project team developed weekly dashboards with which the organizational leaders could monitor questionnaire submissions. A cover letter providing assurance of confidentiality accompanied the questionnaire. The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board reviewed the study and determined that it did not meet the regulatory definition of research involving human subjects.

Questionnaire Content

The questionnaire included 30 items about the structure and process of infection prevention at the nursing home, with a specific focus on CAUTI prevention (see Supplementary Material).Reference Mody, Saint, Galecki, Chen and Krein 12 , Reference Montoya, Chen, Galecki, McNamara, Lansing and Mody 13 Facilities provided the following nursing home-specific information: ownership (VA vs non-VA), number of residents, number of subacute care beds, physical proximity to a VA hospital (VA nursing homes only), and the numbers of physicians, registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and certified nursing aides per 100 beds. Data regarding the nursing home’s infection preventionists, including duration at current position, hours spent on infection prevention–related activities, and training were also collected. For VA nursing homes, questions were included on whether the infection preventionist’s area of responsibility was nursing home care only or if they had broader responsibilities as part of their affiliated medical center infection prevention program. Facilities were also asked about the following items: (1) presence of a committee at the nursing home that routinely reviews HAIs; (2) types of resident services delivered, including 24-hour onsite supervision by a registered nurse, access to laboratory services including blood draws and urine tests, radiology services on both weekends and weekdays, and care provided for residents with intravenous infusions, wounds, tracheostomies, ventilators, and indwelling urinary catheters; and (3) availability of subacute care and rehabilitation on site. Questions assessing the presence of CAUTI prevention policies were asked, including appropriate indications for catheter use and catheter insertion documentation. A series of 5-point Likert-scale questions on catheter utilization and management practices were used to determine how regularly various CAUTI prevention practices were implemented. Responses of 4 (often) or 5 (always) were defined as “regular use” of the respective prevention practice, and responses of 3 (sometimes), 2 (rarely), or 1 (never) were defined as “not regular use.” The CAUTI surveillance domain included questions on tracking changes in CAUTI rates over time, creating CAUTI rate reports, and sharing the reports with leadership and frontline personnel.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics were generated to assess both general and infection prevention–related characteristics of respondent nursing homes. Facility and infection prevention program characteristics of VA and non-VA nursing homes were compared using a 2-sample t test for continuous variables and Pearson’s χ2 test for categorical variables. Multivariable logistic regression was used to examine the associations between facility ownership type (VA vs non-VA) and the presence of urinary catheter use policies, catheter management practices, and surveillance procedures. Models were adjusted for the number of residents in the facility, providing short-term sub-acute rehabilitation, presence of an HAI committee, infection prevention–specific training, and an infection preventionist with 3 or more years of experience with infection prevention programs. All analyses were performed using Stata version 13.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Responding Facility Characteristics

Of 494 facilities from 41 states, representatives of 353 facilities completed the questionnaire (71% response rate), with a 75% response rate (n=47 from 25 states) from VA nursing homes and a 71% response rate (n=306 from 28 states) from non-VA nursing homes. Respondents included directors of nursing (n=135), infection preventionists (n=52), facility administrators (n=41), assistant directors of nursing (n=34), nurse managers (n=17), staff development/education coordinators (n=27), quality managers (n=11), minimum data set (MDS) coordinators (n=8), staff nurses (n=6), advanced practice nurses/nurse practitioners (n=5), and others (ie, medical directors, pharmacists, and those with multiple clinical roles; n=17).

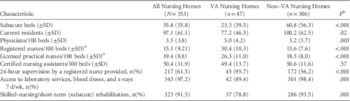

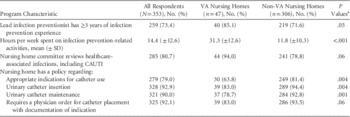

The mean number of subacute beds and facilities providing subacute services were lower in VA nursing homes than in non-VA nursing homes (Table 1). A total of 10 VA nursing homes reported that they provide care for residents with spinal cord injuries. VA nursing homes had higher physician-to-bed ratios than non-VA nursing homes (5.0 vs 3.2 per 100 beds; P=.003), as well as higher ratios of registered nurse staffing to beds (30.4 vs 13.6 per 100 beds; P<.001). A higher percentage of VA nursing homes also reported having 24-hour registered nurse supervision than non-VA nursing homes (96% vs 56%; P<.001). Moreover, 85% of VA nursing homes had an infection preventionist with ≥3 years of relevant experience, and 94% reported having a formal committee that reviewed HAIs. Among non-VA nursing homes 72% had an infection preventionist with ≥3 years of relevant experience, and 79% reported having a formal committee that reviewed HAIs (Table 2). VA nursing homes also reported more hours per week devoted to infection prevention–related activities (31 hours vs 12 hours; P<.001). Most VA nursing homes (77%) were physically connected to an acute care hospital, and most VA nursing home infection prevention programs were part of their affiliated VA acute care hospital program (98%). More than 80% of our respondents reported that their infection preventionist was also responsible for infection prevention in the attached acute-care VA hospital.

TABLE 1 Characteristics of Veterans and Non-Veterans Affairs Nursing Home Respondents Enrolled in the AHRQ Safety Program for Long-term Care: Healthcare-associated Infections/Catheter-associated Urinary Tract Infection (HAIs/CAUTI) Collaborative

NOTE. VA, Veterans Affairs.

a Facilities reporting more than 50 registered or licensed practical nurses per 100 beds were excluded as outliers (n=51).

b P values represent comparisons between VA and non-VA nursing homes using χ2 test for categorical variables and t-test for continuous variables. P<.05 were considered statistically significant.

TABLE 2 Infection Prevention Program Characteristics and Catheter Use Policies

NOTE. VA, Veterans Affairs; CAUTI, catheter-associated urinary tract infection.

a P values in the final column represent significance value of the coefficient for the urinary catheter management strategy represented in each row that was estimated using multivariate logistic regression models adjusted for number of residents in facility, short-term subacute rehabilitation offered, presence of an HAI committee, infection prevention training, and infection preventionist with 3 or more years of experience. P<.05 were considered statistically significant.

Indwelling Urinary Catheter Utilization Policies and Management Practices

The percentage of nursing homes with specific indwelling urinary catheter utilization policies is shown in Table 2. Overall, a lower percentage of VA nursing homes reported having policies concerning appropriate catheter use or catheter insertion than non-VA nursing homes. For example, only 64% of VA nursing homes had policies specifying the appropriate indications for catheter use compared with 81% of non-VA nursing homes (P=.004). The percentage of VA nursing homes that reported a physician order was required to insert a urinary catheter (83% vs 94%, P=.06) was also lower than in non-VA nursing homes.

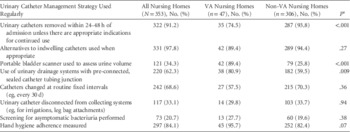

With respect to CAUTI prevention practices, a higher percentage of VA nursing homes compared to non-VA nursing homes regularly use bladder scanners to assess urinary retention (89% vs 26%; P<.001) and urinary catheter drainage systems with pre-connected, sealed catheter tubing junctions (81% vs 60%; P=.009) (Table 3). Most nursing homes in both groups reported considering alternatives to indwelling catheters when appropriate, inserting catheters using aseptic technique, and keeping urinary drainage bags below the level of the bladder.

TABLE 3 Indwelling Urinary Catheter Management Strategies

a P values in the final column represent significance value of the coefficient for the urinary catheter management strategy represented in each row that was estimated using multivariable logistic regression models adjusted for number of residents in facility, short-term subacute rehabilitation offered, presence of an HAI committee, infection prevention training, and infection preventionist with 3 or more years of experience. P<.05 were considered statistically significant.

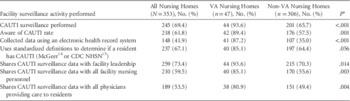

CAUTI Surveillance Activities

Of all responding nursing homes, 69% reported that they conducted CAUTI surveillance prior to joining the AHRQ Safety Program (Table 4). However, compared with non-VA nursing homes, the percentage of VA nursing homes conducting CAUTI surveillance was substantially higher (94% vs 66%; P <.001). When evaluating specific CAUTI surveillance practices, more VA nursing homes reported keeping records of residents with CAUTI using an electronic spreadsheet, database, or logbook (85% vs 53%; P<.001). Additionally, higher percentages of VA nursing homes were aware of their CAUTI rates, collected data using an electronic health record system, and used standardized definitions to define CAUTI prior to the program (Table 4). A significantly higher percentage of VA nursing homes than non-VA nursing homes also reported tracking CAUTI over time (92% vs 67%; P=.014), creating CAUTI summary reports (89% vs 59%; P=.002), and sharing the results with facility leadership (94% vs 70%; P=.014), nursing personnel (85% vs 56%; P=.003), and physicians (81% vs 49%; P=.004). In addition, 77% of VA nursing homes report their CAUTI rates to the VA Inpatient Evaluation Center.

TABLE 4 CAUTI Surveillance Activities

NOTE. CAUTI, catheter-associated urinary tract infection; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; NHSN, National Healthcare Safety Network.

a P values represent significance value of the coefficient for the surveillance activity represented in each row that was estimated using multivariate logistic regression models adjusted for number of residents in facility, short-term subacute rehabilitation offered, presence of an HAI committee, infection prevention training, and infection preventionist with 3 or more years of experience. P<.05 were considered statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

In this national cohort of federally funded VA nursing homes and community-based, non-VA nursing homes, we found key differences in their overall approaches to infection prevention, resources allocated to infection prevention, and CAUTI prevention practices. First, VA nursing homes have substantially higher ratios of physician and nurse staffing to beds than non-VA nursing homes. Second, most VA nursing home infection prevention programs are integrated within their respective VA acute care infection prevention programs and have more infection prevention–related resources. Third, while more non-VA nursing homes report having established catheter utilization policies, they were less likely to conduct CAUTI surveillance.

The VA healthcare system is the nation’s largest integrated healthcare delivery system and provides comprehensive healthcare services to veterans across the United States. Prior research studies have shown that care provided by the VA system exceeds that of other healthcare providers in several areas.Reference Asch, McGlynn and Hogan 16 – Reference Krein, Hofer and Kowalski 21 Studies comparing VA and non-VA patients have, for example, shown better performance on measures of chronic disease and preventive care,Reference Asch, McGlynn and Hogan 16 greater rates of evidence-based drug therapy,Reference Trivedi, Matula, Miake-Lye, Glassman, Shekelle and Asch 17 and better outcomes for older men who are hospitalized for several cardiac conditions.Reference Nuti, Qin and Rumsfeld 18 Several studies have also shown that VA hospitals are leaders in the use of key practices to prevent catheter-related blood stream infections.Reference Evans, Kralovic and Simbartl 19 – Reference Krein, Hofer and Kowalski 21 Consistent with these studies, we found better CAUTI surveillance practices within VA nursing homes. Most VA nursing homes (94%) conduct CAUTI surveillance and report their CAUTI rates to the VA Inpatient Evaluation Center (77%), emulating VA acute care surveillance practices.Reference Render, Hasselbeck, Freyberg, Hofer, Sales and Almenoff 22 Moreover, use of standardized surveillance definitions is more common among the VA nursing homes than the non-VA nursing homes. We believe that the centralized infrastructure of the VA, increased numbers and training of staff, and the use of national VA benchmarks and leadership engagement likely account for these findings.Reference Render, Freyberg and Hasselbeck 23

On the other hand, the non-VA nursing homes we surveyed report greater use of catheter utilization policies. Non-VA nursing homes were more likely than VA nursing homes to have a policy requiring documentation of appropriate indications for catheter use, appropriate catheter insertion and maintenance practices, as well as requiring a physician’s order to place a urinary catheter. A higher percentage of non-VA nursing homes also reported that urinary catheters are removed within 24–48 hours of admission than VA nursing homes. This is likely, in part, because non-VA nursing home certification as a Medicare and/or Medicaid nursing home provider includes adhering to established regulatory guidance from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) on the appropriate use of indwelling urinary catheters as well as public reporting of the prevalence of indwelling urinary catheters. 24 – 26 These regulations have enhanced several processes of care, including reducing the use of indwelling catheters (from 9% to 5%) in non-VA nursing homes.Reference Hawes, Mor and Phillips 27 – Reference Castle, Engberg, Wagner and Handler 29 In contrast, in a nationwide sample of all VA nursing homes, 11% of 10,939 residents had an indwelling urinary catheter.Reference Tsan, Langberg and Davis 30 This high urinary catheter utilization rate within VA nursing homes may be due to the predominantly older male population with greater prevalence of urinary outlet obstruction, a higher percentage of residents with spinal cord injuries, as well as a higher percentage of residents receiving end-of-life care.

Our findings have important implications for both policy and practice, as non-VA nursing homes become further integrated with acute care facilities under emerging Medicare Accountable Care Organization (ACO) programs. ACO programs are expected to provide better coordination and a higher quality of care, which could translate to financial benefits through, for example, reduced readmissions. Infections remain a major cause of readmission to acute care hospitals. 3 Including nursing homes within the ACOs has the potential to improve continuity of care, quality of care, resident satisfaction, fewer inappropriate transfers, and reductions in the spread of antimicrobial resistanceReference van den Dool, Haenen, Leenstra and Wallinga 31 and infections. Furthermore, to control spending pertaining to infections for care spanning acute, post-acute, and long-term care settings, infection prevention programs between hospitals and partnering nursing homes could be aligned. This alignment would foster adoption of best practices from both VA and non-VA nursing homes, including surveillance for common infections, reduced device utilization, joint antimicrobial stewardship programs, and training to reduce infection-related hospitalizations and enhance outcomes.Reference McWilliams, Chernew, Zaslavsky and Landon 32

Our study has important limitations. First, this study was conducted within a collaborative setting with voluntary participation of interested nursing homes, leading to a self-selection bias. Furthermore, there is a potential for reporting bias because we did not conduct actual observations or in-depth interviews to confirm the questionnaire findings. Second, we do not have information concerning resident demographics, their diagnoses, or comorbidities. The collection of data regarding individual resident characteristics was beyond the scope of this project. Some differences in reported resources and practices may be related to a difference in the populations served. Third, participating facilities identified their own team leader, who was often a director or associate director of nursing, to coordinate program activities at the facility. Thus, while the facility team would likely include an infection preventionist, the survey respondent may or may not have been an infection preventionist. Finally, our findings suggest that future studies evaluating infection prevention personnel resources should be designed to further characterize time required in conducting hospital versus nursing home infection prevention activities.

Limitations notwithstanding, this study fills some important gaps in the literature. No studies have compared infection prevention programs of VA and non-VA nursing homes. In our study, we identified the potential benefits of integrated healthcare systems such as the VA in implementing surveillance practices and the role of regulatory agencies such as the CMS in reducing catheter utilization in community-based nursing homes. Best practices from both settings should be universally adopted and promoted to reduce infections, enhance use of evidence-based practices, and improve resident safety in the nursing home setting.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support: This work was supported by a contract from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), US Department of Health and Human Services (contract no. HHSA 290201000025I). Other funding/support was provided by the following: the National Institutes of Health (grant no. R01 AG41780 and K24 AG050685 to Mody; grant no. NIH DK092293 to Trautner); the University of Michigan Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (grant no. NIA P30 AG024824 to Mody); AHRQ (grant nos. K08-HS019767, P30HS024385, and R01HS018334 to Meddings); Department of Veterans Affairs (grant no. VA RRP 12–433 to Trautner); Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston, Texas (grant no. CIN13–413 to Trautner); VA National Center for Patient Safety Patient Safety Center of Inquiry (to Saint); and a VA Health Services Research and Development Research Career Scientist Award (grant no. RCS 11–222 to Krein).

Potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Saint has received fees for serving on advisory boards for Doximity and Jvion. Dr. Meddings has received honoraria for lectures and teaching related to prevention and value-based purchasing policies involving catheter-associated urinary tract infection and hospital-acquired pressure ulcers. She has also received honoraria from RAND Corporation/AHRQ for preparation of an AHRQ chapter update on the prevention of catheter-associated UTI. Dr. Trautner has received honoraria for speaking from Baylor Scott & White, Texas A&M Health Sciences Center. She has provided consultation for Zambon Pharmaceuticals and Lasergen. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2016.279