Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) is associated with increased healthcare utilization, morbidity, and mortality in the United States. 1,Reference Lucado, Gould and Elixhauser2 In 2011, there were nearly 500,000 CDIs, and an estimated 107,600 of these began in the hospital, defined as hospital onset >3 calendar days after admission. Reference Bouwknegt, van Dorp and Kuijper3 In an effort to reduce CDI incidence, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) require hospitals to report hospital-onset (HO)-CDI rates. In addition to monitoring progress, HO-CDI rates are used to compare and rank hospitals for pay-for-performance reimbursements. 4

For such reimbursements, the CDC National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) uses a standardized infection ratio (SIR) to adjust HO-CDI rankings regarding interfacility differences among hospitals. 5 The risk adjustment calculation for HO-CDI includes community-onset CDI prevalence, CDI test type, facility size, and facility type. 6 However, the SIR does not account for patient-level risk factors that may contribute to CDI. Hospitals with seemingly high rates of HO-CDI may have patient populations with inherently higher risk of CDI, which is not accounted for in the risk adjustment. For meaningful hospital comparisons, it is important both to determine nonmodifiable patient-level characteristics associated with HO-CDI and to adjust for such risk factors in the SIR.

Important patient-level risk factors for CDI have been previously described in the literature, including the use of antibiotics, proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs), and H2 receptor blockers, all of which are modifiable targets for stewardship efforts based on inappropriate use. Reference Garey, Sethi, Yadav and DuPont7–Reference Eze, Balsells, Kyaw and Nair9 Multiple studies have also identified comorbid conditions, which are typically not preventable, as risk factors for CDI. Reference Eze, Balsells, Kyaw and Nair9–Reference Rodemann, Dubberke, Reske, Seo and Stone14 Furthermore, electronically available comorbidities captured by International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes were associated with HO-CDI at a single tertiary-care center. Reference Harris, Sbarra and Leekha15 Another study identified laboratory findings upon acute-care admission to be associated with HO-CDI, including elevated creatinine level, abnormal platelet level, and elevated leukocyte level. Reference Tabak, Johannes, Sun, Nunez and McDonald16 To our knowledge, no study has analyzed whether electronically available comorbidities together with laboratory values on admission are risk factors for HO-CDI in a multiple-hospital setting, and furthermore, no study has analyzed the effect of these additional variables on hospital SIRs.

In this study, we had 2 aims: (1) to evaluate whether patient comorbidities, as captured by ICD-10-CM discharge codes, and laboratory values obtained within 24 hours of admission are associated with HO-CDI across multiple institutions when controlling for age, antibiotic use, and antacid use and (2) to develop 2 methodologies that incorporate electronically available comorbidities into the SIR and determine whether the resultant SIRs, compared to the current SIR, change hospital ranking and improve risk adjustment for HO-CDI.

Methods

Study cohort and data source

We performed a retrospective cohort study among patients aged at least 18 years admitted to 1 of 3 hospitals in Maryland between January 1, 2016, and January 1, 2018. Hospital 1 is a 767-bed academic center; hospital 2 is a 170-bed community hospital; and hospital 3 is a 218-bed community hospital. Institutional review board approval was granted by the University of Maryland, Baltimore, with a waiver of informed consent. The cohort was assembled using University of Maryland Medical System’s central data repository, which contains both administrative and clinical data from electronic medical records. The information extracted from electronic medical records included age, gender, race, times of admission and discharge, laboratory testing results within 24 hours of admission, medication information, ICD-10-CM codes, C. difficile test collection time, and C. difficile test result if clinically indicated. Laboratory test results were extracted for hematocrit, hemoglobin, platelet count, leukocytes, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), bicarbonate, creatinine, glucose, sodium, and potassium. Data were validated in a manual comparison of the extracted data with the electronic medical record performed by at least 1 researcher on >1,500 key fields (eg, C. difficile test date and result, administrative data, laboratory results, and medication). The data within this repository for this study and for previous research studies had positive and negative predictive values >99%. Reference Harris, Jackson and Robinson17–Reference Harris, Fleming and Bromberg20

For SIR calculations, CDI LabID data were extracted from the NHSN for each hospital during the study period. To correctly capture the method and variables used by the CDC risk adjustment, we downloaded data for the following NHSN risk adjustment factors: test type, facility type, number of ICU beds, number of beds, community onset prevalence, medical school teaching status, and emergency department reporting.

Variable definitions

A patient was considered to be positive for HO-CDI if they had a positive C. difficile test collected >3 calendar days after hospital admission and no positive result within the previous 14 days (ie, the CDC NHSN definition of HO-CDI). 21 Patients admitted more than once during the study period were included as separate admissions and were controlled in the analysis. We mapped ICD-10-CM codes from electronic medical records to comorbidities in the Elixhauser comorbidity index, as outlined by Quan et al. Reference Quan, Sundararajan and Halfon22 Each patient was assigned 30 new binary variables, representing each individual comorbidity. For each patient, we also calculated an unweighted Elixhauser score, which was the sum total of their comorbidities with 1 point per comorbidity. For example, if a patient had 4 comorbid conditions, the patient would be assigned an Elixhauser score of 4. Reference Quan, Sundararajan and Halfon22,Reference Elixhauser, Steiner, Harris and Coffey23 The mean daily Elixhauser score in each hospital refers to the mean Elixhauser score of hospitalized patients per day in the study period. For example, if a patient with an Elixhauser score of 5 were hospitalized from January 1, 2016, to January 7, 2016, the patient would contribute 7 days of a score of an Elixhauser score of 5 in calculating the hospital mean.

Antibiotic, PPI, or H2 blocker use was defined as the patient having received at least 1 dose of the medication after hospital admission and before C. difficile test collection time for patients with HO-CDI or during the entire admission for patients without HO-CDI. Antibiotic use was analyzed in individual classes in the bivariate analysis. Nonsystemic antibiotic formulations (eg, intravitreal), oral vancomycin, and fidaxomicin were not considered antibiotic exposures in this study. Laboratory results were analyzed as binary variables (eg, normal or abnormal), representing whether the laboratory value fell within the thresholds reported by the hospital’s clinical laboratory for a given individual.

Regression analysis

Each hospital was analyzed individually in a regression analysis. Bivariate associations between HO-CDI and covariates were assessed using log-binomial regression. Multivariable models were computed with log-binomial regression using covariates with significant associations in the bivariate analysis (P < .10). We used 2 methods to build the multivariable models for each hospital: (1) a model in which the Elixhauser score was considered as a continuous predictor and (2) a model in which 30 individual Elixhauser comorbid conditions were included as binary predictors (and Elixhauser score was excluded). The models were fit using maximum likelihood with stepwise selection, and covariates were retained if they met the significance level of <.05.

SIR model development and comparison

Because comorbid conditions, as represented both by the Elixhauser score and by individual components, were deemed significant risk factors for HO-CDI in the present study, we sought to augment comorbidities to the current SIR to analyze whether this could improve HO-CDI risk adjustment for the patient case-mix variability among hospitals not fully represented by the current methodology. We did not analyze the effect of including laboratory values in the SIR because these were not strongly associated with HO-CDI in this study. For each of 3 risk adjustment methods, we calculated the hospital SIR by dividing the observed number of HO-CDI events by the predicted number of HO-CDI events. The following 3 methods were used to calculate the predicted number of HO-CDI events: (1) current CDC NHSN risk adjustment methodology; (2) current CDC NHSN methodology plus patient Elixhauser score; and (3) current CDC NHSN methodology plus patient individual Elixhauser comorbid conditions.

For method 1, we computed the predicted number of infections for each site using the current CDC NHSN model. 6 For each facility, we calculated the expected daily rate based on the CDC parameters and facility-level variables (eg, CDI community prevalence, CDI test type, number of ICU beds, total number of beds, presence of an emergency department, oncology hospital, general hospital, and teaching hospital). 6 The resulting value was multiplied by total CDI patient days for the given facility: the sum of all inpatient days for those without HO-CDI, and the sum of the time until HO-CDI in patients with HO-CDI.

For method 2, we augmented the existing parameters from the current CDC model with the Elixhauser score. The daily CDI rate was calculated using facility-level information from the CDC NHSN parameter estimates. 6 We included the log of this CDC daily rate as a predictor along with Elixhauser score in a Poisson regression model including all 3 hospitals. Poisson was chosen because the CDC expected rate was based on person-time analysis. For each site, we calculated all patient rate events per day using the given parameter estimates obtained. Patient daily rates were multiplied by the patient’s length of stay or time until positive CDI result. We summed all patient daily rates to obtain the expected HO-CDI events per facility.

For method 3, we used the same methodology as outlined for method 2, but individual comorbid conditions were candidate predictor variables in place of the Elixhauser score. To select the individual comorbid conditions variables for inclusion, we used stepwise regression with a significance level of <.05 as the minimum requirement for entry and retention in the model.

Facility SIRs from methods 2 and 3, in which comorbidities were included in the risk adjustments, were compared with SIRs obtained using the CDC methodology (method 1). Percentage changes in SIRs calculated from method 1 to methods 2 and 3 were recorded. An SIR >1 indicates that the hospital reported a higher number of HO-CDI than expected, whereas an SIR <1 indicates that the hospital reported a lower number of HO-CDI than expected. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Regression results

At hospital 1, 48,057 patient admissions met the inclusion criteria during the study period; among them, 314 (0.65%) had an HO-CDI. At hospital 2, 41 (0.47%) of the 8,791 patients admissions had HO-CDI. At hospital 3, 75 of 29,136 patients (0.26%) had an HO-CDI. The characteristics of patients at the 3 hospitals are shown in Table 1. Hospital 2 had the highest mean Elixhauser score per admission, but hospital 1 had the greatest mean daily Elixhauser score (ie, mean Elixhauser score of inpatients per day). Hospital 1 also had the longest length of stay (or time prior to infection if HO-CDI was present) (Table 1). At each site, patients with HO-CDI were more likely to be older, to use antibiotics, and to use PPIs. Also, the mean Elixhauser score in patients with HO-CDI was significantly higher than in patients without HO-CDI (P < .001) (Table 2). In the bivariate analysis for each of the hospitals, age, antibiotic use, PPI use, H2 blocker use, Elixhauser score, and several individual comorbidities and laboratory values were significantly associated with HO-CDI at the P < .10 level.

Table 1. Selected Characteristics of Patients Admitted to Each of Three Hospitals Between January 1, 2016, and January 1, 2018

Note. SD, standard deviation.

a Refers to the mean Elixhauser score per admission.

b Refers to the mean Elixhauser score per day in the study period.

c Corresponds to the time in the hospital until infection with hospital-onset Clostridioides difficile infection, or the total length of stay otherwise.

Table 2. Characteristics of Patients Admitted to Three Hospitals Between January 1, 2016, and January 1, 2018, Stratified by HO-CDI Status

Note. HO-CDI, hospital-onset Clostridioides difficile infection; SD, standard deviation.

a P values are for t tests or χ Reference Lucado, Gould and Elixhauser2 tests as appropriate for continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

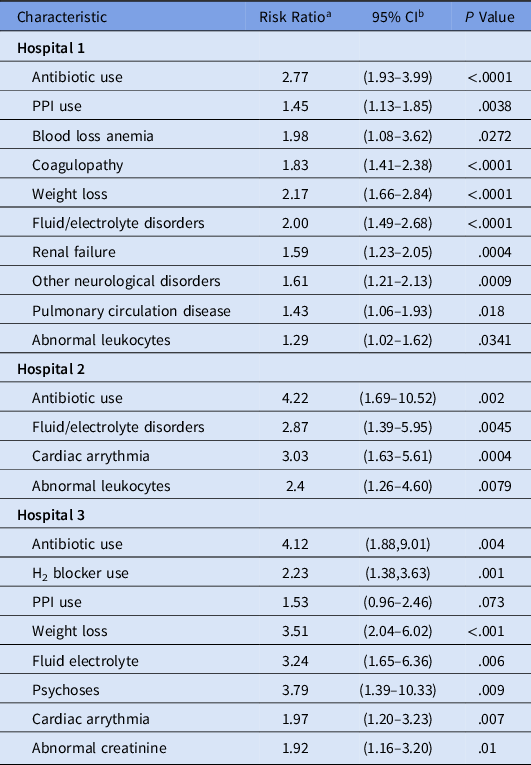

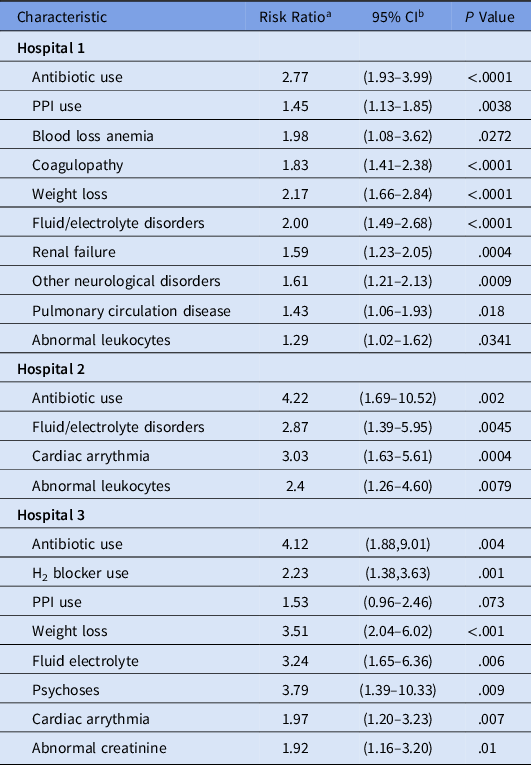

The results for the hospital-specific multivariable log-binomial regression models are shown in Table 3. At hospital 1, Elixhauser score and abnormal leukocyte level were significant risk factors for HO-CDI when controlling for age, antibiotic use, and antacid therapy. At hospital 2, Elixhauser score and hospital-admission abnormal leukocyte level were significant risk factors for HO-CDI after controlling for confounders. At hospital 3, Elixhauser score and abnormal creatinine level were factors associated with HO-CDI. Table 4 presents the regression analysis results when individual comorbid conditions were assessed in place of the Elixhauser score. Fluid and electrolyte disorders were significant risk factor at all 3 hospitals, whereas cardiac arrhythmia was a significant risk factors at 2 facilities. Abnormal leukocyte level remained significant at hospitals 1 and 2, whereas abnormal creatinine level was a significant risk factor for HO-CDI at hospital 3.

Table 3. Multivariable Regression Models of HO-CDI with Elixhauser Score

Note. HO-CDI, hospital-onset Clostridioides difficile infection; CI, confidence interval; PPI, proton pump inhibitor. Covariates assessed include age, gender, antibiotic use, PPI use, H2 blocker use, abnormal laboratory results on admission (hematocrit, hemoglobin, platelets count, leukocyte level, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), bicarbonate, creatinine, glucose, sodium, and potassium), and Elixhauser score.

a Risk ratio estimates were obtained using log-binomial regression.

b Wald 95% CIs.

Table 4. Multivariable Regression Models of HO-CDI with Individual Comorbid Conditions

Note. HO-CDI, hospital-onset Clostridioides difficile infection; CI, confidence interval; PPI, proton-pump inhibitor. Covariates assessed include age, gender, antibiotic use, PPI use, H2 blocker use, abnormal laboratory results on admission (hematocrit, hemoglobin, platelets count, leukocytes, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), bicarbonate, creatinine, glucose, sodium, and potassium), and Elixhauser score.

a Risk ratio estimates were obtained using log-binomial regression.

b Wald 95% CIs.

SIR model results

When incorporated with the CDC’s facility-level risk adjustment in method 2, Elixhauser score was a statistically significant factor, with a resultant risk ratio of 1.19 (P < .001). In method 3, several comorbid conditions were statistically significant when added to the facility-level adjustment: complicated hypertension (RR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.42–0.89), neurologic complications (RR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.08–1.73), chronic pulmonary disease (RR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.06–1.61), renal failure (RR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.36–2.16), lymphoma (RR, 3.25; 95% CI, 2.26–4.68), coagulopathy (RR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.18–1.79), weight loss, (RR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.24–1.97), fluid/electrolyte disorders (RR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.53–2.44), blood loss anemia (RR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.17–3.30), and depression (RR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.57–1.00).

Table 5 shows the results of the CDC NHSN SIR (method 1), the CDC NHSN method plus Elixhauser score (method 2), and the CDC NHSN method plus individual comorbidities (method 3). For the academic center (hospital 1), incorporating both Elixhauser score and individual comorbid conditions into the risk adjustment led to an increase in the number of predicted HO-CDI events and corresponding decreases in the SIRs of 2% and 7% for methods 2 and 3, respectively (Table 5). In contrast, SIRs for both community hospitals (hospitals 2 and 3) increased using both methods, meaning that incorporating comorbidities into the risk adjustment for hospitals 2 and 3 led to a decrease in the number of predicted HO-CDI events. Although including The Elixhauser score (method 2) did alter each facility’s SIR, the hospital ranking remained unchanged. Using method 3, the hospital rankings did change; hospital 2’s SIR increased by 12%, making it the hospital with the highest SIR (ie, the worst-performing hospital). Although it increased by 20%, hospital 3’s SIR remained the lowest of the 3 SIRs in method 3.

Table 5. HO-CDI Events Observed and Predicted by SIR Models Using CDC Risk Adjustment Model (Method 1) and Risk Adjustment Models Incorporating Elixhauser Score (Method 2) and Individual Comorbidities (Method 3) for the Study Period, January 1, 2016, to January 1, 2018

Note. HO-CDI, hospital-onset Clostridioides difficile infection; SIR, standardized infection ratio, CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

a Percentage change of the addition of Elixhauser score (method 2) to the CDC NHSN SIR (method 1).

b Percentage change of the addition of individual comorbidities (method 3) to the CDC NHSN SIR (method 1).

Discussion

In this study, Elixhauser score (or more comorbid conditions identified by discharge codes) was a factor associated with HO-CDI at multiple institutions when controlling for confounding variables such as age, antibiotic use, and antacid use. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have shown comorbidities to be important risk factors, and it provides further evidence that electronically available comorbidities are associated with HO-CDI. Reference Eze, Balsells, Kyaw and Nair9–Reference Harris, Sbarra and Leekha15

We developed 2 methodologies of calculating the SIR that take comorbid conditions into consideration: one with the Elixhauser score (method 2) and one method with individual Elixhauser comorbidities (method 3). Both new models adjust for comorbid conditions in addition to the hospital-level risk factors adjusted for in the current CDC NHSN model (eg, CDI community prevalence, CDI test type, ICU bed number, and hospital type). Both methodologies have high feasibility for risk adjustment because ICD-10-CM codes are standard across hospitals. Elixhauser score, which is a sum of patient comorbid conditions encoded by ICD-10-CM codes, may be much easier to incorporate into a large-scale summary measure for nationwide risk adjustment, whereas the individual comorbidities may provide more insight into specific conditions that are significantly associated with HO-CDI. In our analysis, we demonstrated that adding these patient-level comorbidities, both with Elixhauser score and individual comorbid conditions, consistently influenced the SIR; however, only method 3, which incorporated individual comorbid conditions, influenced the SIR-based hospital rankings.

In method 2, hospital 1’s SIR decreased, meaning that the additional risk adjustment for Elixhauser score caused that hospital’s predicted number of HO-CDI events to increase. This result is consistent with the data in Table 1, which shows patient comorbidity levels across facility. Although hospital 1 (academic) has a mean Elixhauser score across patient admissions of 3.47 (vs 3.80 for hospital 2), its mean daily Elixhauser score per day across admissions is the greatest of the 3 hospitals. Thus, the patients at hospital 1 with more comorbidities tended to stay longer. Conversely, hospital 2 (community) had the highest mean Elixhauser score, but its mean daily Elixhauser score was lower than that of hospital 1, which factors into hospital 2’s slight increase in SIR when comparing method 2 to the CDC NHSN method.

For method 3, the SIR for hospital 3 (community) increased by the largest amount after incorporating individual comorbid conditions. Table 1 displays how hospital 3 patients are less likely to have many of the comorbid conditions used as predictors in the model, which can account for the 20% increase in SIR. Furthermore, the rankings of hospital 1 and 2 changed with method 3: hospital 2 became the worst-performing hospital, whereas hospital 1’s SIR decreased. Compared to the other hospitals, hospital 2 (community) has a relatively lower rate of coagulopathy and lymphoma, and a higher rate of depression (which is inversely associated with HO-CDI). This community hospital has a less complex case mix, which is correctly captured in this model. Including a larger number of hospitals in future SIR modeling with inclusion of comorbidities may allow for more optimal parameter estimates for each of the individual comorbidities and thus may improve model accuracy.

The SIR ranking is an important metric for hospital reimbursements. 5,6 Hospitals ranked in the bottom 25% (ie, hospitals with the highest SIRs) of all hospitals receive a 1% payment reduction from CMS, so it is essential to produce a risk adjustment model for interhospital comparisons that consider both hospital and patient-level differences to best represent a facility’s CDI prevention efforts. 4 Notably, rankings did not change when the Elixhauser score was included in the risk adjustment (method 2); however, our analysis included only 3 hospitals. The SIRs did change, however, with absolute changes of 0.02 to 0.16, which would likely cause ranking alterations if more hospitals had been included in the analysis. Our analysis suggests that the Elixhauser score and individual comorbidities can possibly capture some of the nonmodifiable case mix among hospitals not fully represented by the facility variables in the CDC NHSN model alone, which might allow for more fair hospital comparison and reimbursement.

In our regression analysis, no single laboratory value on admission was a significant factor associated with HO-CDI across all 3 hospitals. Abnormal leukocyte level at hospital admission was a risk factor in 2 hospitals, and abnormal creatinine level was a risk factor in 1 hospital. Abnormal leukocyte level may be a surrogate indicator for underlying infection in patients having an increased risk of antibiotic exposure, which had a strong association in each of the models. Likewise, abnormal creatinine level is correlated with other features that may have had stronger significance, including renal failure or a higher Elixhauser score, or sepsis, possibly represented by an abnormal leukocyte level. In a previous study, laboratory values within 24 hours of admission were risk factors for HO-CDI, including leukocyte level >11,000 mm Reference Bouwknegt, van Dorp and Kuijper3 and creatinine level > 2.0 mg/dL, but these researchers did not include antibiotic therapy and comorbid conditions as candidate predictors for their model. Reference Tabak, Johannes, Sun, Nunez and McDonald16 Further investigations regarding whether laboratory values on admission are associated with HO-CDI should be conducted.

The main limitation of the present study is that it was performed at 3 hospitals in Baltimore, Maryland, which limits comparisons among SIR rankings. Additionally, laboratory results within 24 hours of admission were analyzed as binary variables; although this eases the interpretation of the test results, we lost information using this method. Furthermore, not all patients had laboratory testing performed within 24 hours of admission. Another potential limitation is that the unweighted Elixhauser score was used for analysis. We chose to use an unweighted score because it is simple for hospitals to understand and apply. However, weighted Elixhauser comorbidity indices also exist, although they have only been validated for predicting mortality, not HO-CDI. Future study is warranted to evaluate whether developing a weighted score specific to HO-CDI could further improve model performance. Reference van Walraven, Austin, Jennings, Quan and Forster24–Reference Moore, White, Washington, Coenen and Elixhauser26 Lastly, criticisms of the use of ICD-10-CM codes in research include the underreporting of patient comorbidities when compared with the medical record and that they could reflect codes that maximize reimbursement. Reference Quan, Parsons and Ghali27–Reference Leal and Laupland29 However, several validation studies have demonstrated high specificities (98%–100%) when comparing comorbidities captured in administrative electronic databases to manual chart review, which refutes the suggestion that there is a misrepresentation of patient conditions for reimbursement purposes. Reference Leal and Laupland29,Reference Quan, Li and Duncan Saunders30

We have confirmed the work of previous studies that electronically available comorbid conditions are important risk factors for HO-CDI. We have illustrated how using patient-level comorbidities in addition to facility-level factors alters the SIR for HO-CDI and could potentially be added to the current CDC NHSN risk adjustment to better account for nonmodifiable patient-level risk factors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yuan Wang for database maintenance and abstraction. The opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Financial support

This project was partially supported by from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant no. R01HS022291) and by the NIAID, US Department of Health and Human Services (grant no. 5K24AI079040). Additionally, this project was supported in part by the Proposed Research Initiated by Students and Mentors (PRISM) Program, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Office of Student Research, and by Grants for Emerging Researchers/Clinicians Mentorship, Infectious Disease Society of America.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.