Flexible gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopes have been associated with patient infections and outbreaks, even when reprocessed correctly according to available manufacturer instructions.Reference Epstein, Hunter and Arwady 1 , Reference Wendorf, Kay and Baliga 2 It is now recognized that current reprocessing guidelines may not be sufficient and that additional research is needed to identify optimal practices for endoscope disinfection. One area of debate centers on the length of time a properly reprocessed flexible GI endoscope can be stored before use. Among subject experts there is no agreement regarding a safe maximum storage interval. The Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN) 2016 Guideline for Processing Flexible Endoscopes states that the collective evidence regarding the maximum safe storage time for processed endoscopes is inconclusive, and that a multidisciplinary team should establish a policy for its own institution.Reference Burlingame, Denholm and Link 3 In 2000, the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC) recommended an interval of 7 days before reprocessing.Reference Alvarado and Reichelderfer 4 A 2011 multisociety guideline on reprocessing flexible GI endoscopes (which was endorsed by these two professional societies in addition to the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, and several others) provided no recommendation, noting that reuse of endoscopes within 10–14 days of reprocessing appears to be safe, but that the data are insufficient to provide a maximum storage interval.Reference Petersen, Chennat and Cohen 5 This guideline recommended further research to better define this interval.

Several authors have attempted to clarify this question by evaluating storage times for reprocessed endoscopes. In 2015, a systematic review of the available evidence on this topic found that contamination rates of reprocessed endoscopes were low and pathogens were rare, suggesting that appropriately disinfected endoscopes could be stored for at least 7 days.Reference Schmelzer, Daniels and Hough 6 However, given the resource requirements and complexity of endoscope reprocessing, a substantial savings of labor and cost could be realized if a longer maximum storage interval were found to be safe. We performed a prospective study to assess the association between storage time and endoscope contamination in a pediatric GI procedural unit, with the goal of evaluating whether longer storage intervals result in meaningful scope contamination.

METHODS

We conducted this study in 2 phases. The first phase occurred in December 2013 and consisted of a cross-sectional evaluation of 9 GI endoscopes (6 gastroscopes, 2 duodenoscopes, and 1 colonoscope) that had been in storage for more than 7 days since reprocessing. Of the 9 endoscopes, 8 had been hanging in nonventilated cabinets and 1 gastroscope had been hanging in a ventilated cabinet. For each scope, we collected cultures from 3 different locations of the endoscope (ie, external surface of the hand piece and channel ports, external surface of the insertion tube, and internal channels). After a sterile field was set up, the endoscope was removed from the storage cabinet in a manner to minimize contamination and hung vertically from either an intravenous administration (i.v.) pole or the suspension arm of the endoscope cart. After donning sterile gown and gloves, a sterile swab moistened with sterile saline was placed into each channel port (suction, air/water, and biopsy) and rotated 5 times, then the swab was rolled over the surface of the hand piece and outside rim of the deflection control knob. The swab tip was then cut off using sterile scissors into a sterile tube with 1 mL sterile saline. Next, for the insertion tube culture, a sterile 3×3-cm gauze moistened with 5 mL sterile saline was wiped using a squeezing and twisting motion along the entire shaft of the scope and then rubbed 3 times over the distal tip before being placed into a sterile container with 50 mL sterile saline. Third, for the internal suction and air- or water-channel culture, the scope was placed onto the sterile field and 30–60 mL sterile saline was flushed through the suction channel port followed by 30–60 mL air. The effluent from the distal end of the insertion tube was collected into a sterile container. This procedure was repeated once with an additional 30–60 mL sterile saline and air through the air/water channel. This effluent was collected into the same sterile container as the effluent from the suction channel. Finally, a sterile disposable channel-cleaning brush was passed 3 times down the channels: 2 passes down the suction cylinder (1 straight on and another at a 45° angle) and the last pass down the instrument channel. Finally, the brush tip was cut with sterile scissors into the container holding the flush effluent.

The second phase of the study was performed from February through May 2014 and consisted of a prospective evaluation of endoscope contamination. The same 9 flexible endoscopes described above were removed from clinical use and underwent routine reprocessing, that is, manual cleaning followed by high-level disinfection with CIDEX OPA in an automated endoscope reprocessor (Custom Ultrasonics, Ivyland, PA). After reprocessing, the scopes were hung vertically in an unventilated cabinet and underwent the same culturing protocol outlined above at 1 week after reprocessing (without being used for patient care in the interim). After these cultures were collected, all scopes were then reprocessed again and hung for 2 weeks without use, after which time they were cultured again. We then repeated these reprocessing and culture procedures after 4 weeks, 6 weeks, and 8 weeks without use (with repeat reprocessing before each hanging cycle began).

All specimens were cultured for bacteria and fungi using standard microbiologic techniques. The sample spun in a vortexer for 30 seconds. A pair of plates (5% sheep’s blood agar plate and Sabouraud dextrose agar plate, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes NJ) was cultured with 0.1 mL or 0.01 mL of sample. The blood agar plate was incubated for 48 hours at 35°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere and the Sabouraud dextrose agar was incubated for 5 days at 30°C in air. At the end of the incubation, the number of each type of colony was counted and each colony type was identified using standard methods in the clinical laboratory. A priori, we defined a clinically relevant level of contamination as >100 CFU/mL.Reference Alfa, Sepehri, Olson and Wald 7 The Wilcoxon rank-sum exact test was used to compare the distribution of storage intervals between scopes with positive and negative cultures from phase 1 of the study. The Boston Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board reviewed the protocol and deemed it to be exempt because it did not involve human subjects.

RESULTS

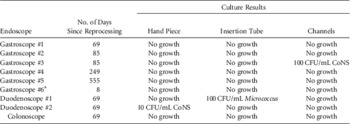

In phase 1 of the study, the endoscopes had been hanging unused for a median of 69 days (range, 8–555 days) since reprocessing. Of the 27 cultures, 3 (11.1%) collected from these endoscopes were positive, all at ≤100 CFU/mL. Table 1 displays the details of these culture results. The only organisms recovered from the scopes were bacteria that are considered common commensals of skin (coagulase-negative Staphylococcus and Micrococcus). There was no statistical difference in the median storage interval between scopes with positive cultures (69 days) and those with negative cultures (77 days, P=.82).

TABLE 1 Culture Results From Stored Flexible GI Endoscopes

NOTE. CoNS, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus.

a Had been stored in ventilated cabinet.

In phase 2 of the study, 7 of 131 cultures (5.3%) were positive, all at ≤100 CFU/mL. Table 2 displays the details of these cultures. Of the 5 different organisms that were recovered from endoscopes at varying storage intervals, 4 of these were bacteria that are typically considered non-pathogenic commensals of either skin or the upper respiratory tract. A single culture from the channels of 1 colonoscope grew 10 CFU/mL of Candida albicans after 14 days of hanging. No enteric gram-negative bacteria were recovered from any endoscope at any time.

TABLE 2 Prospective Cultures of Gastrointestinal Endoscopes After Reprocessing and StorageFootnote a

NOTE. CoNS, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus.

a Unless noted otherwise, each of the 9 endoscopes had 3 cultures submitted (hand piece, insertion tube, and channels) at each time point.

b Culture from gastroscope #2 channels were not submitted because of inadvertent contamination during sample collection.

c Cultures from duodenoscope #1 were not collected because the scope was pulled for clinical use before day 56.

DISCUSSION

Flexible endoscopes can remain persistently contaminated despite reprocessing according to guidelines.Reference Ofstead, Wetzler and Doyle 8 The combination of the complex design of the instruments and the number and detailed nature of the steps required to correctly reprocess them creates a risk of potential inadequate disinfection.Reference Bourdon 9 Employees responsible for endoscope reprocessing have reported feeling pressure to complete the work quickly to facilitate clinical workflow, further complicating the problem.Reference Ofstead, Wetzler, Snyder and Horton 10

In this context, efforts to simplify the process or reduce the frequency at which endoscope reprocessing is required could reduce the labor and time invested. Whether properly reprocessed endoscopes could be stored for longer intervals before use remains an open question. In this study, we found that contamination rates remained low even at storage intervals up to 8 weeks after reprocessing, and when cultures were positive, they nearly all represented low-virulence commensal bacteria in low colony counts. Previous studies assessing contamination rates of endoscopes have found similarly low rates of contamination over shorter storage intervals. Rejchrt et alReference Rejchrt, Cermak, Pavlatova, McKova and Bures 11 assessed scope contamination after 5 days of storage and found that only 4 of 135 cultures were positive; bacteria were only isolated from external surfaces and all of the organisms were skin flora (coagulase-negative staphylococci and Corynebacterium). Riley et alReference Riley, Beanland and Bos 12 collected cultures from 1 colonoscope at 1 week after reprocessing and only 2 of 15 cultures were positive (coagulase-negative staphylococcus and Micrococcus, at 1 CFU each). Vergis et alReference Vergis, Thomson, Pieroni and Dhalla 13 evaluated 7 GI endoscopes at 1 week after reprocessing, and only 1 scope culture was positive but at a higher colony count (coagulase-negative Staphylococcus at 700 CFU/mL).

Few studies have assessed longer storage intervals. Brock et alReference Brock, Steed, Freeman, Garry, Malpas and Cotton 14 evaluated 10 stored GI endoscopes by culturing the channels (but not the surface) at days 7, 14, and 21 (without reprocessing after each culturing step).Reference Brock, Steed, Freeman, Garry, Malpas and Cotton 14 They found a higher overall contamination rate of 29.2% (28 of 96 cultures), and 12 of 24 cultures collected on day 21 were positive. However, only 4 isolates during the study were judged to be pathogens; 1 of these was from day 21 and was Candida parapsilosis at a concentration of 1 CFU/mL. They concluded that a storage time of 21 days is likely safe. Ingram et alReference Ingram, Gaines, Kite, Morgan, Spurling and Winsett 15 cultured 4 colonoscopes at intervals ranging from 3 to 56 days and found no medically significant growth at any of the time points studied.

The efficacy of endoscope disinfection can be assessed using several methods, including both culture and nonculture techniques (eg, bioburden assays, adenosine triphosphate [ATP] bioluminescence, or quantitative polymerase chain reaction).Reference Shin and Kim 16 Several studies have suggested that the sensitivity and specificity of ATP bioluminescence are too low to recommend its use for monitoring reprocessing of endoscopes.Reference Hansen, Benner, Hilgenhoner, Leisebein, Brauksiepe and Popp 17 , Reference Batailler, Saviuc, Picot-Gueraud, Bosson and Mallaret 18 While US guidelines do not currently recommend routine culturing of endoscopes, in 2015 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offered a protocol for obtaining cultures from duodenoscopes for facilities that wish to implement periodic microbiologic monitoring. 19 A consensus has not been reached regarding the level of contamination that requires intervention. For our study, we chose to define clinically relevant contamination as >100 CFU/mL as recommended in a prior study in which only 2 of 383 scope channel cultures (0.5%) collected over a 7-month period grew bacteria in concentrations higher than this benchmark.Reference Alfa, Sepehri, Olson and Wald 7 However, other authors have used alternate cutoffs for alerts or action, often ranging from 5 to 25 CFU.Reference Heeg 20 – Reference Saviuc, Picot-Gueraud and Shum Cheong Sing 22 The CDC surveillance protocol suggests that any quantity (≥1 CFU) of high-concern organism (including enteric Gram negative bacteria, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and Enterococcus) warrants repeat reprocessing and investigation of potential reprocessing breaches. 23 For low-concern microbes (eg, coagulase-negative staphylococci, Bacillus species, and diphtheroids), the CDC protocol states that <10 CFU typically does not require intervention, whereas interpretation of ≥10 CFU of low-concern organisms should be considered in the context of typical culture results at the facility. 23

Our study has several strengths, including evaluation of longer storage intervals than prior published studies, the inclusion of cultures from both internal and external endoscope components, and a protocol that required reprocessing after every culture collection to minimize the potential for contamination related to handling the scopes during culturing. We are also aware of several limitations. The lower limits of sensitivity for the cultures have not been determined. We evaluated a small number of endoscopes because the equipment was needed for clinical work. In addition, because all scopes were reprocessed using a single model of automated endoscope reprocessor, the results may not be generalizable to other reprocessing methods. Finally, our study was not designed to address microbial contamination of endoscopes after reprocessing failures.

In conclusion, we found that only 5% of properly reprocessed and stored flexible GI endoscopes showed evidence of contamination over intervals of up to 8 weeks after reprocessing, and when contamination was detectable, it was nearly always with low-concern organisms and always at colony counts ≤100 CFU/mL. These data suggest that a safe storage interval for endoscopes may be longer than currently recommended in available guidelines. Additional efforts are warranted to define an approach to endoscope storage that optimizes both patient safety and the workload associated with management of these complicated devices.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support. No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Potential conflicts of interest. Alexander J. McAdam reports being a Scientific Advisory Board Member for Bacterioscan and having received honorarium as an editor for the American Society for Microbiology, neither related to the current work. All other authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.