Antibiotic-resistant organisms (AROs) present a major infection control threat for patients in hospitals, and they increase the risk of serious healthcare-associated infections. Hospital environmental surfaces can become contaminated with AROs and may contribute to ARO transmission, either directly or via the hands or clothing of healthcare personnel (HCP). Reference Boyce1–Reference Mitchell, Spencer and Edmiston5 Contact precautions (gowns and gloves) have been an essential component of infection prevention practices to limit transmission of AROs. Reference Muto, Jernigan and Ostrowsky6 However, there has been debate regarding whether contact precautions are effective in reducing ARO transmission. Reference Morgan, Murthy and Munoz-Price7–Reference Rubin, Samore and Harris9

The relationships among environmental contamination, HCP cross contamination, and ARO transmission are difficult to study. Previous studies have demonstrated that contaminated hospital surfaces can contribute to the spread of nosocomial infections. Reference Chen, Knelson and Gergen10–Reference Huang, Datta and Platt12 Other studies have demonstrated ARO transfer from infected patients or contaminated surfaces to the hands and clothing of HCP. Reference Hayden, Blom, Lyle, Moore and Weinstein13–Reference Kwon, Burnham and Reske17 However, few studies have focused on the relationship between contaminated surfaces in patient rooms and the risk of HCP cross contamination outside patient rooms. Reference Duckro, Blom, Lyle, Weinstein and Hayden18

Additional studies that examine the associations between environmental surface contamination, HCP cross contamination and ARO transmission patterns, and the impact of contact isolation practices on these associations, are needed to better inform policies and procedures for the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and to reduce ARO transmission and healthcare-associated infections (HAIs). Surrogate markers, such as fluorescent powder (FP) and MS2, a nonpathogenic bacteriophage, are unique tools for studying ARO transmission and cross contamination in hospitals. Reference Alhmidi, Koganti, Tomas, Cadnum, Jencson and Donskey19,Reference Koganti, Alhmidi, Tomas, Cadnum, Jencson and Donskey20 Fluorescent powder and MS2 have been used to study HCP self-contamination while donning/doffing PPE Reference Kwon, Burnham and Reske17,Reference Casanova, Alfano-Sobsey, Rutala, Weber and Sobsey21,Reference Bell, Smoot, Patterson, Smalligan and Jordan22 and the effectiveness of hospital cleaning procedures. Reference Fattorini, Ceriale and Nante23–Reference Hung, Chang and Cheng25

The aim of this prospective cohort study was to assess ARO transmission and cross contamination patterns in real-world hospital settings using 2 surrogate markers (FP and MS2 bacteriophage) and selective bacterial cultures.

Methods

This study was conducted in a general medicine ward, a medical intensive care unit (ICU), and an emergency department (ED) at a 1,260-bed tertiary-care academic hospital in St Louis, Missouri. Patients aged ≥18 years hospitalized between September 16, 2015, and February 9, 2016, as well as HCP caring for the enrolled patients were eligible for inclusion. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Washington University Human Research Protection Office. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or a legally authorized representative. Participating HCP provided verbal consent prior to study participation.

Patient enrollment

Two patients on contact precautions for vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) were enrolled for each patient not on contact precautions. At enrollment, each patient’s room was scanned for fluorescence using an ultraviolet (UV) light. If fluorescence was detected, the area was wiped clean before surrogate marker application. For patients on contact precautions, flocked swab collection kits (ESwab, Copan Diagnostics, Murietta, CA) were used to collect swabs from each of the surfaces targeted for surrogate marker application and to collect nasal, axilla, inguinal, and stool or rectal swabs from each patient. Baseline patient and environmental samples were determined using selective bacterial culture.

Surrogate marker application

In each patient room, 4 high-touch surfaces were selected for surrogate marker application: the front of the patient’s gown, the top of each bed rail, and the bedside table or computer mouse. Fluorescent powder (0.02 g, Glo Germ, Moab, UT) was applied to each surface using a brush applicator. MS2 bacteriophage (1:10 dilution of commercially available stock solution in viral transport medium, 1.0 × 108 PFU/mL per site, Reference Kwon, Burnham and Reske17 ZeptoMetrix, Buffalo, NY) was applied using an atomizer (Teleflex, Morrisville, NC).

HCP enrollment and observations

Following surrogate marker application, trained study coordinators observed each patient room for 2–4 hours from the hallway. During this period, HCP hand hygiene (HH) compliance at room entry and exit, defined as the use of alcohol hand rub or soap and water, were recorded, and the first 3 surfaces that each HCP touched after exiting the room were flagged for later assessment. Also, 3–4 HCP who entered the room during the observation period were recruited for study participation.

Sample collection

After the first visit to a patient’s room, participating HCP had their hands, face and hair, and clothing scanned with a UV light to identify areas of fluorescence. For patients on contact precautions, UV scanning was performed after the HCP had removed PPE. HCP were assessed only once, even if they visited the room multiple times. At the end of the observation period, the patient’s room, the first 3 surfaces that each participating HCP had touched after exiting the room, and 4 additional locations on the study ward (ie, medication cabinet, door handles, nurse’s station, and elevator buttons) were scanned for fluorescence.

Areas that fluoresced were photographed and trained study coordinators collected surface samples using a viral transport collection kit (Quidel, San Diego, CA). Additional samples were collected from the 4 locations on the study ward and from each participating HCP hands and gloves, face (ie, periorbital, nasal, and oral areas), and sleeve and wrist. These samples were tested for the presence of MS2.

If the patient was on contact precautions, flocked swab collection kits were used to collect additional samples from each area where fluorescence was observed and from the 4 selected locations on the study ward. One pooled sample was also collected from the face, hands, and wrists of each participating HCP. These swabs were submitted for selective bacterial culture.

After sample collection, the surfaces where the surrogate markers had been applied and any areas where fluorescence was observed were wiped clean to prevent further transmission of FP and MS2. Each patient room was used only once to further minimize the possibility of residual marker from a previous patient.

Bacterial culture

Swabs collected to identify MS2 contamination had RNA extracted from the transport medium using the QIAamp viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). Real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to detect MS2 bacteriophage using the Cepheid Smart Cycler (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA).

Swabs associated with patients on contact precautions were cultured for VRE, MRSA, and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). Swabs were plated to CHROMID VRE chromogenic medium (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étiole, France) to select for VRE; on Spectra MRSA chromogenic agar (Remel, Lenexa, KS) to select for MRSA; and on 5% sheep’s blood agar (Hardy Diagnostics, Santa Maria, CA) to recover MSSA. All swabs were also inoculated to 6.5% NaCl broth (Hardy Diagnostics) as an enrichment method to recover VRE, MRSA, and MSSA if these did not grow on the primary plated media. When growth was observed, 4 colonies of each type of organism were subcultured and identified using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) using VITEK MS. Reference Manji, Bythrow and Branda26–Reference McElvania TeKippe and Burnham28 After bacterial identification was confirmed, phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibly testing and repetitive sequence-based PCR (repPCR) were performed. Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) typing was performed on all S. aureus isolates. Reference El Feghaly, Stamm, Fritz and Burnham29,Reference Fritz, Hogan and Singh30

Statistical analysis

Patterns in the location and type of surrogate marker detections were evaluated qualitatively. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals and the χ2 or Fisher exact test were used to characterize associations between predictor and outcome variables. Predictor variables included patient contact isolation status and type of HCP. Outcome variables included FP, MS2, and VRE, MRSA, or MSSA detections in patient rooms, on HCP, and/or on surfaces touched by HCP. The use of HH by HCP at room entry and exit were assessed as both predictor and outcome variables. Two measures of HCP HH compliance were examined: (1) HH at the first room visit by participating HCP and (2) HH over all room visits by all HCP. The first measure was used to determine the association between HH and surrogate marker detections, and the second provided a more complete picture of HH practices overall. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 24.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Results

In total, 25 patients were enrolled: 10 in the medicine ward, 10 in the ICU, and 5 in the ED. Among them, 17 patients (68%) were on contact precautions for VRE (n = 12), MRSA (n = 4), or VRE and MRSA (n = 1). In addition, 77 HCP participated in the study: half (n = 40, 52%) were nurses (n = 35), nurse practitioners (n = 3), or student nurses (n = 2). Other participating HCP included physicians (n = 16, 21%), patient care technicians (n = 9, 12%), respiratory therapists (n = 4, 5%), radiology technicians (n = 2, 3%), dieticians (n = 2, 3%), 1 pharmacist (1%), a pharmacy student, an infection preventionist, and a unit secretary.

Fluorescent powder detections

In 20 patient rooms (80%), fluorescence was detected on at least 1 site outside the areas where FP had been applied, most commonly on the computer keyboard (n = 15), the counter (n = 7), or the door handle (n = 5). In 3 cases, fluorescence was also detected in the study ward, at the nurses’ station (n = 2) or on the medication cabinet (n = 1). Moreover, fluorescence was detected on 26 HCP (34%): on their body, hands, or clothing (n = 23) and/or on a surface they touched after exiting the patient’s room (n = 10). Examples of FP detections are shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Examples of fluorescent powder (FP) detections observed in this study.

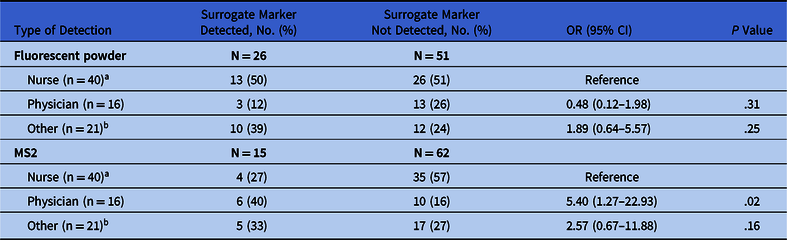

The HCP caring for patients on contact precautions had significantly fewer FP detections, on themselves and/or on the surfaces they touched, than HCP caring for patients not on precautions (19% vs 70%; P < .001) (Table 1). We found no significant difference in the rates of FP detection among different types of HCP (Table 2).

Table 1. Fluorescent Powder and MS2 Detections on Participating Healthcare Personnel (HCP) and Surfaces Touched by Participating HCP After Exiting the Patient’s Room, by Patient Isolation Status

Note. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

a Fisher’s exact test was used for comparisons due to small cell sizes.

b Defined as the visualization of fluorescence when the HCP or surface was scanned with a handheld UV light.

c Includes HCP hands, sleeves/wrist, gloves, face, and clothing.

d Environmental surfaces touched by HCP after leaving the patient room.

e Defined as the detection of MS2 on a swab collected from the HCP or surface via real-time reverse-transcriptase PCR.

Table 2. Fluorescent Powder and MS2 Detections on Participating Healthcare Personnel (HCP) and/or Surfaces Touched by HCP Type

Note. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

a Includes nurse practitioners and student nurses.

b Includes patient care technicians, respiratory therapists, radiology techs, dieticians, pharmacist, pharmacy student, infection prevention technician, and unit secretary.

MS2 detections

MS2 was detected in 9 patient rooms (36%), most commonly on the computer (n = 4) and, outside 1 room, on a medication cabinet. Moreover, 15 HCP (19%) had MS2 detections, either on their body or clothing (n = 10) and/or on surfaces touched after exiting a patient room (n = 6), most commonly the door handle (n = 3). Also, 1 HCP had MS2 identified on 2 sites on the body or clothing, and 1 HCP had MS2 identified on 2 touched surfaces.

In general, MS2 was recovered less frequently on HCP and/or surfaces touched by HCP caring for patients on contact precautions than on HCP caring for patients not on precautions, but these differences did not reach statistical significance (Table 1). MS2 was more often detected on physicians than on nurses (40% vs 27%; P = .02) (Table 2).

Bacterial culture results

Of the patients on contact precautions, 12 (71%) had baseline swabs positive for the ARO for which the patient was placed on contact precautions. Also, 2 patients, 1 on precautions for MRSA and 1 for VRE, had swabs positive for both MRSA and VRE. One patient on precautions for VRE had baseline swabs positive for MSSA.

Moreover, 7 patients on contact precautions (41%) had 1 or more room surfaces with a positive baseline bacterial culture (Table 3). For 6 patients, the organism identified was the organism that triggered contact precautions; 2 patients had surfaces that were also positive for MSSA. The remaining patient, who was on precautions for VRE but had a baseline swab positive for MSSA, had baseline room surface swabs that were also positive for MSSA.

Table 3. Microbiologic Culture Results for the Patients on Contact Precautions and the Healthcare Personnel (HCP) Who Cared for These Patients

Note. VRE, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; NA, not applicable.

a MSSA is not an indication for contact precautions.

b Included nasal, axilla, inguinal skin, and stool or rectal swabs.

c For 12 patients, the identified organism matched the reason for contact precautions; 2 patients had swabs that were positive for both VRE and MRSA; 1 patient had swabs that were positive for only MSSA.

d Repetitive sequence-based PCR (repPCR) results were variable: samples from 1 patient were type B; samples from 4 patients were type C; samples from 2 patients were types B and C; samples from 1 patient were types A, B, and C; and samples from 1 patient were types A, D, E, and F.

e Samples from 4 patients were repetitive sequence-based PCR (repPCR) type B and staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) type IV. Samples from 1 patient were repPCR types E and G, SCCmec type III.

f Samples were repPCR types C and B, SCCmec type III.

g For 6 patients, the identified organism matched the reason for contact precautions; 1 patient had baseline room surface swabs that were positive for both MRSA and MSSA; and 1 patient had swabs that were positive for both VRE and MSSA. One patient had baseline room-surface swabs that were positive for only MSSA.

h Baseline room-surface samples from 2 patient rooms were all repPCR type C; samples from the third room were repPCR types D and F.

i Samples from 2 rooms were repPCR type B, SCCmec type IV. Samples from one room were repPCR types E and G, SCCmec type III.

j Samples from the first room were repPCR type B, SCCmec type III. Samples from the second room were repPCR type E, SCCmec type I. Samples from the third room were repPCR types B and D, SCCmec type III.

k Samples were repPCR types D and E.

l These samples were repPCR type A, SCCmec type I.

m One HCP had samples that were repPCR type A, SCCmec type III; 1 HCP had samples that were repPCR type B, SCCmec type III; 1 HCP had samples that were repPCR type E, SCCmec type I; 3 HCP had samples that were repPCR type F, SCCmec type III; 1 HCP had samples that were repPCR types A, C, and D, SCCmec type III; and 1 HCP had samples that were repPCR types E and D, SCCmec type III.

n Samples were repPCR type C.

o Two surfaces touched by the same HCP had samples that were positive for MSSA types H and A, SCCmec type III.

Among the swabs collected from surfaces where fluorescence was observed, only 2 had a positive bacterial culture (Table 3). One sample, from the foot of a bed, was positive for VRE. The other, from an elevator button, was positive for MSSA. Both were associated with the same patient, who had a baseline swab positive for VRE.

Of the 54 HCP who cared for a patient on contact precautions, 8 (15%) had a positive pooled swab, all of which were positive for MSSA (Table 3). These HCP had cared for 4 different patients, none of whom had a baseline swab positive for MSSA, but one of whom had a baseline room surface positive for MSSA.

Only 2 HCP (4%) who cared for a patient on contact precautions had a touched surface with a positive bacterial culture (Table 3). The first, a blood glucose monitor, was positive for VRE, although the HCP was positive for MSSA, and MRSA was identified in the patient’s room. The second, a door handle, was positive for MSSA and was touched by an HCP who was also positive for MSSA, although VRE was identified in the patient’s room.

Among samples that were positive for VRE, 6 strain types were identified by repPCR. The most common, type C, was associated with 8 patients, 3 of whom were also positive for type B. Among these, 2 patients had VRE type C identified in both patient and room-surface samples. Another patient had multiple VRE types (A, D, E, F) identified in patient and room-surface samples.

Among samples that were positive for S. aureus, 9 strain types were identified by repPCR (3 among MRSA samples and 8 among MSSA samples); 4 strain types were identified by SCCmec typing. Also, 4 of the 5 patients who were positive for MRSA and 2 of the 3 patients with room surfaces positive for MRSA had the same strain typing (repPCR B, SCCmec IV). Among 8 HCP who were positive for MSSA, 7 had the same SCCmec type (III). Of these samples, 3 were repPCR type F; the others had diverse repPCR typing.

HCP hand hygiene observations

Both measures of HCP HH compliance yielded similar estimates. HH compliance was lower at room entry than at room exit. Only 18% of HCP performed HH at room entry (14 of 77 first visits by participating HCP and 54 of 298 total HCP visits), and 52% performed HH at room exit (40 of 77 first visits and 54 of 290 total visits).

The HCP HH compliance at room entry did not differ by patient isolation status (Table 4). However, compliance at room exit was better among the HCP caring for patients on contact precautions than among HCP caring for patients not on precautions: 61% versus 30% first room visits (P = .02) and 58% versus 37% all room visits (P < .01). We observed no differences in HH compliance at first room visit for nurses versus physicians or other HCP (Table 5). However, when considering all room visits, nurses were more likely than other nonphysician HCP to perform HH at room entry (25% vs 8%; P < .01) and were more likely than physicians to perform HH at room exit (59% vs 43%; P = .03).

Table 4. Healthcare Personnel (HCP) Observations Where Hand Hygiene Was Performed, at First Room Entry/Exit and All Room Entries/Exits, by Patient Isolation Status

Note. OR, odds ratio; CU, confidence interval.

a The Fisher exact test was used for comparisons due to small cell sizes.

b 8 room-exit observations were missing because room exit could not be observed.

Table 5. Healthcare Personnel (HCP) Hand Hygiene Observations, at First Room Entry/Exit and All Room Entries/Exits, by HCP Type

Note. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

a Includes student nurses and nurse practitioners.

b Includes patient care technicians, respiratory therapists, radiology techs, dieticians, pharmacist, pharmacy student, infection prevention technician, and unit secretary.

c 8 room-exit observations were missing because room exit could not be observed.

The association between HCP HH and surrogate marker detections is shown in Table 6. Although few associations were observed between either HH measure and surrogate marker detections, HCP who performed HH immediately after the first room exit and before being swabbed were less likely than HCP who did not perform HH at room exit to have fluorescence detected (20% vs 49%; P = .008).

Table 6. Association Between Hand Hygiene Performance at Room Exit and Detection of Fluorescence and MS2 on Healthcare Personnel (HCP) and on Environmental Surfaces Touched by HCP

Note. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

In this study, the transfer of both FP and MS2 were observed both inside and outside patient rooms, on participating HCP, and on surfaces touched by HCP after exiting patient rooms. Transfer of FP occurred more frequently than the transfer of MS2, and positive bacterial cultures were even less frequent.

Although few studies have utilized both FP and MS2 as surrogate markers, some have also reported higher rates of FP compared to MS2 detections. Reference Kwon, Burnham and Reske17,Reference Casanova, Erukunuakpor and Kraft31 Others have reported similar detection rates Reference Alhmidi, Koganti, Tomas, Cadnum, Jencson and Donskey19,Reference Tomas, Kundrapu and Thota32 or more frequent MS2 detections. Reference Casanova, Alfano-Sobsey, Rutala, Weber and Sobsey21 This lack of agreement may indicate that neither marker performs significantly better than the other, or it may be related to differences in the means of detection (visual versus swabs). However, the 2 markers are thought to model different types of contamination: FP may model gross bacterial contamination and MS2 may simulate viral contamination events. Reference Casanova, Alfano-Sobsey, Rutala, Weber and Sobsey21 Therefore, different detection rates may be reasonable. More data are needed to determine which surrogate markers are better models for the study of ARO transmission.

In contrast to surrogate markers, bacterial culture may identify actual ARO transmission events. This study focused on 2 AROs that routinely trigger contact precautions, MRSA and VRE, as well as MSSA. Although MSSA does not routinely trigger contact precautions, it is a clinically relevant pathogen that causes significant morbidity in hospitalized patients. Reference Thomsen, Kadari and Soper33,Reference Hassoun, Linden and Friedman34 The greater frequency of surrogate marker detections as compared to ARO detections may suggest that FP and MS2 overrepresent the likelihood of ARO transmission. Previous studies using MS2 to model the spread of Clostridioides difficile spores have also reported more frequent MS2 detections versus bacterial detections on HCP skin and clothing. Reference Alhmidi, Koganti, Tomas, Cadnum, Jencson and Donskey19,Reference Alhmidi, John and Mana35 However, in our study, both surrogate markers were present in all of the patient rooms, and only 7 rooms had surfaces positive for VRE, MRSA, or MSSA at baseline. Therefore, the lower rate of positive bacterial cultures was not unexpected.

In this study, both surrogate markers were identified less frequently among HCP caring for patients on contact precautions versus HCP caring for patients not on contact precautions, although the difference only reached significance for FP. We also observed that HCP caring for patients on contact precautions more frequently performed HH at room exit and that HCP who performed HH had fewer FP detections. Previous studies have also reported an association between contact precautions and HH compliance Reference Bearman, Marra and Sessler36,Reference Harris, Pineles and Belton37 and between HH and fewer MS2 detections on the hands of HCP. Reference Sassi, Sifuentes and Koenig38,Reference Julian, Leckie and Boehm39 These findings suggest that both contact precautions and HH play an important role in preventing the spread of AROs, and they provide additional data to support the role of contact precautions in preventing ARO transmission.

Although we found no significant differences in the rate of FP detections among different types of HCP, MS2 was more frequently detected among physicians than among nurses. This observation may also be related to HH because nurses were more likely than physicians to perform HH at room exit. As in prior studies, Reference Mastrandrea, Soto-Aladro, Brouqui and Barrat40 observed HCP HH compliance was low. However, differences in HH compliance by HCP job category suggest that a role exists for interventions promoting HH among all HCP.

A key strength of this study is the use of multiple surrogate markers and bacterial cultures, which helps to generate a more complete model of pathogen transmission. Other strengths include the real-world hospital setting and detailed HCP observations. This study also had several limitations. The small sample size may have limited the statistical power to detect differences in surrogate marker detections. This study also only included patients on contact precautions for VRE and MRSA, and we only tested for VRE, MRSA, and MSSA. Therefore, it is unclear how our findings would translate to other AROs, such as C. difficile and multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria. Finally, despite detailed HCP observations, it was not always possible to observe HH that occurred inside patient rooms when the door was closed. Therefore, we may have underestimated HCP HH compliance; however, our internal, routine HH observations indicate that HH compliance among hospital staff is less than ideal overall.

Despite these limitations, this study demonstrated transfer of both FP and MS2 beyond the initial areas of contamination inside patient rooms. Our findings suggest that both surrogate markers may be useful tools for studying ARO transmission. Larger studies using surrogate markers to assess ARO transmission and HCP cross-contamination are warranted, especially those focusing on the impact of contact precautions on ARO transmission.

Acknowledgments

The study team acknowledges the assistance and support of the nursing and staff members at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in this project.

Financial support

This study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (grant no. 3U54CK000162-05S1). The fluorescent powder used in this study was donated by the Glo Germ Company (Moab, UT). Glo Germ did not play a role in the development of the study design or result interpretation. Dr Kwon is also supported by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH grant no. UL1TR000448, subaward KL2TR000450) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant no. 1K23AI137321-01A1).

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article.