Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is one of the most frequently identified antimicrobial-resistant pathogens that cause skin and soft-tissue infections (SSTIs); it is associated with subsequent infections, high mortality rates, and increased healthcare costs. Reference Keene, Vavagiakis and Lee1 Recent increased clinical precautions across the nation have resulted in a decrease of invasive MRSA infections. Reference Peterson, Boehm and Beaumont2,Reference Marshall, Richards and Mcbryde3 However, further advances in screening methods need to be investigated to continue to decrease the burden of MRSA infections. Reference Dantes, Mu and Belflower4 Staphylococcus aureus is naturally present in the nares, axilla, groin, and skin of many people, with the nares being the most common site of colonization. Reference Mermel, Cartony, Covington, Maxey and Morse5 Data from previous studies note that 7% of patients Reference Jarvis, Jarvis and Chinn6 and 4.3%–15% of emergency healthcare workers in United States hospitals are colonized with MRSA. Reference Bisaga, Paquette, Sabatini and Lovell7,Reference Suffoletto, Cannon, Ilkhanipour and Yealy8 Nasal colonization with MRSA has been shown to be a risk factor for subsequent infection with the pathogen, Reference Davis, Stewart, Crouch, Florez and Hospenthal9 and the anterior nares are the source of MRSA infections in different sites in some patients. Reference Jinadatha, Hussain, Erickson, Villamaria, Copeland and Huber10

In 2007, VA hospitals nationwide implemented MRSA nasal screening by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in an effort to reduce healthcare-associated MRSA infections. Reference Jain, Kralovic and Evans11 Currently, nasal screening for MRSA is used as a means to prevent the spread of the pathogen in the hospital setting. Reference Jain, Kralovic and Evans11 Moreover, nasal screening for MRSA may also be a helpful tool in de-escalating antibiotic therapy in the treatment of infections in the hospital setting. Reference Radigan12 In an age of rising antibiotic resistance, the use of well-chosen antibiotics is of the utmost importance. Previous studies have shown nasal screening for MRSA to be of significant value for the prediction of respiratory tract cultures. Reference Tilahun, Faust, McCorstin and Ortegon13–Reference Hiett, Patel, Tate, Smulian and Kelly15 In this study, we aimed to help define the predictive value of MRSA nasal screening by PCR to guide the use of MRSA agents preceding results from subsequent wound and tissue cultures in the inpatient setting.

Methods

This single-site retrospective study was conducted at the Fargo VAHCS in Fargo, North Dakota. Veterans’ were included in the study group if they were male or female aged ≥18 years, had been admitted to the Fargo VA between January 2008 and June 2015, and had undergone nasal screening for MRSA by PCR (GeneXpert System, Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA) upon admission, along with culture of a secondary site within 30 days of admission. Secondary sites included wound and tissue sites. A wound culture was defined as a culture taken from superficial wounds such as abrasions, cuts, lacerations, ulcers, burns, or associated skin disease. A tissue culture was defined as a culture taken from a deep wound such as a surgical wound, bite wound, deep trauma, or any specimen that originated from deep tissue.

The following baseline data were collected: age, sex, ethnicity, geographic residence, immunosuppression factors, history of smoking or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, length of stay, history of positive MRSA colonization or infection within the past calendar year, and a history of a previous hospital admission within 30 days. Immunosuppression factors included previous kidney transplant, glomerulonephritis, asplenia, diabetes mellitus, malignancy, HIV or AIDS, diabetes, or hepatitis B, or C. This study was reviewed and approved by the University of South Dakota Institutional Review Board and the Fargo Veterans’ Affairs Health Care System (VAHCS) Research and Development Committee.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome for the study was concordance between MRSA nasal swab results and MRSA wound and tissue cultures determined by the McNemar test for positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV). Reference Lachenbruch16 The Bayes theorem was used to calculate positive likelihood ratio and negative likelihood ratio. Reference Donovan and Bayes’ Theorem17 Linear regressions were performed for all subanalyses. All analyses were conducted utilizing SPSS version 19 statistical software (IBM, Armonk, NY). Data were deemed significant at P < .05.

Results

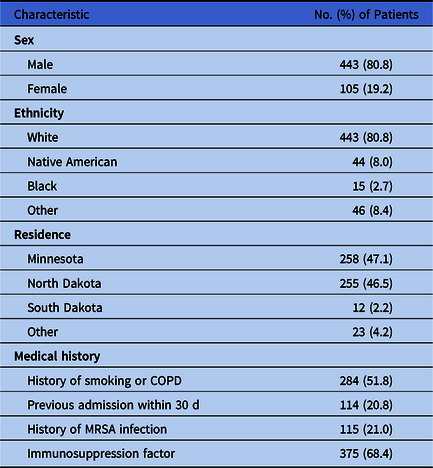

Of the 942 veterans reviewed, 548 met inclusion criteria. Those included were 80.8% male and 19.2% female; 80.8% were white, Native American (8.0%), black (2.7%), and other ethnicity (8.4%). Most study participants resided in Minnesota (47.1%) and North Dakota (46.5%), with the rest being from South Dakota (2.2%) and other locations (4.2%). Furthermore, 51.8% were smokers or had previously been diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD). Also, 20.8% of the participants had been admitted to the hospital within the previous 30 days, and 21.0% had a previous diagnosis of MRSA colonization or infection. In addition, 68.4% had an immunosuppression factor (see Table 1 for patient characteristic breakdowns).

Table 1. Patient Characteristics

Note. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

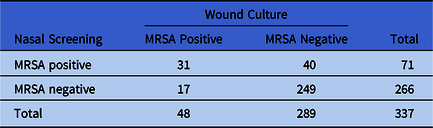

Of the 548 veterans who met our inclusion criteria, 337 had a culture of a wound and 211 had a culture of a tissue site. In total, 71 veterans (21.1%) in the wound-culture group and 41 (19.4%) in the tissue-culture group had a positive nasal swab for MRSA. Furthermore, 31 (9.2%) had both a nasal screening positive for MRSA and a wound culture positive for MRSA, whereas 21 (10.0%) had both a nasal screening positive for MRSA and a tissue culture positive for MRSA. Tables 2 and 3 show the results of nasal screening for MRSA compared with the results of tissue and wound cultures.

Table 2. 2×2 Table Results of Nasal Screening for MRSA Compared With Results of Wound Culture

Note. MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Table 3. Results of Nasal Screening for MRSA Compared With Results of Tissue Culture

Note. MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

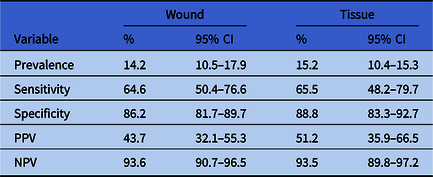

The sensitivities of MRSA nasal screening for detecting culture-proven MRSA were 64.6% and 65.5% for wound and tissue cultures, respectively, and the specificities were 86.2% and 88.8%, respectively. The PPVs were 43.7% for wound and 51.2% for tissue cultures and the NPVs were 93.6% for wound and 93.5% for tissue cultures (Table 4). The positive likelihood ratios were 4.7 for wound cultures and 5.9 for tissue cultures. The negative likelihood ratios were 0.4 for both wound and tissue cultures (Table 5).

Table 4. Prevalence, Sensitivity, Specificity, PPV, and NPV of Nasal Colonization With MRSA for Subsequent Wound or Tissue MRSA Infection

Note. PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Table 5. Likelihood Ratios of Nasal Colonization With MRSA for Subsequent Wound or Tissue MRSA Infection

Subanalyses were conducted using linear regression for medical history variables based on their ability to predict a positive MRSA culture swab. Results from this test indicate that patients with a history of MRSA colonization or infection are significant predictors of positive MRSA tests from both the nasal and tissue cultures (P < .05). Other statistical methods also confirmed these findings. The variables of history of smoking or COPD, previous admission within 30 days, and immunosuppression factors were not significant predictors of a positive MRSA culture swab.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the correlation between the MRSA results of nasal swab testing by PCR and of cultures of wound and tissue samples from veterans admitted to the Fargo VAHCS. The results show relatively low sensitivities and PPVs, demonstrating a limited diagnostic value of positive nasal swab for wound and tissue sites with MRSA. In addition, our calculated negative likelihood ratios of 0.4 offers moderate evidence against the presence of MRSA. According to the Bayes theorem and based on our study prevalence (15.2% for tissues and 14.2% for wounds), those who had a positive nasal screen for MRSA only had a moderately increased probability that their wound or tissue site was also colonized with MRSA (posttest probability of 41.2% for tissues and 50.2% for wounds). Reference Donovan and Bayes’ Theorem17

Because of the high NPVs (93.6% for wounds and 93.5% for tissues), these results indicate that there is reasonably high probability that the subsequent wound and tissue cultures will also be negative. This finding could be valuable for ruling out wound or tissue infection when the nose swab result is negative for MRSA and may help guide the clinician’s decision to hold or discontinue MRSA-active agents. By combining this study’s finding of high NPVs with an appreciable difference in turnaround times between the nasal swab and the culture in detecting MRSA (~70 minutes for nose swab versus 24–48 hours for wound/tissue culture), clinicians can avoid empirical use of MRSA-targeting agents 1–2 days before the final culture results are available. 18,19

Although this study did not investigate whether the MRSA-positive wound and tissue sites were colonized or infected, the study data support using the notion “negative MRSA nose swab indicates no MRSA coverage” as a strategy to avoid overuse of MRSA-targeting agents. The conclusion of this study agrees with the previously published studies analyzing nasal MRSA colonization and wound and tissue culture results. Reference Tilahun, Faust, McCorstin and Ortegon13–Reference Hiett, Patel, Tate, Smulian and Kelly15,Reference Johnson, Wright, Sheperd, Musher and Dang20–Reference Gunderson, Holleck, Chang, Merchant, Lin and Gupta22 In studies specifically analyzing SSTI site culture concordance with nasal swab results, the ability to use predictive values for ruling out MRSA infection have depended on the population size, pretest probability, and disease prevalence.

This study has several limitations. It was a retrospective review conducted at a single VA facility with a limited sample size. However, our findings suggest a strategy for antimicrobial stewardship, and they add to a limited body of research related to MRSA nasal tests and wound and tissue cultures. To confirm our findings in this area, larger prospective studies in different populations are warranted.

In conclusion, the findings of this retrospective study suggest that, in cases of wound or tissue samples for which culture results are pending, a negative MRSA nasal swab can be a valuable indicator for withholding or discontinuing MRSA-active agents.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ashley Carver, Kari Fischer, and Gregory Wieland for their assistance with the chart reviews for this study. These findings are the result of work supported with resources and use of facilities at the Fargo Veterans’ Affairs Health Care System. The contents do not represent the views of the US Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.