Central-line–associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) remain an important target for quality improvement efforts given their impact on patients and healthcare institutions. CLABSIs in pediatric patients are associated with an increased hospital length of stay of 19 days and a cost of US$16,000–$69,000 per event.Reference Goudie, Dynan, Brady and Rettiganti1,Reference Wilson, Rafferty, Deeter, Comito and Hollenbeak2 CLABSI infection rates serve as metrics for hospital rankings and reimbursement negotiations.Reference Dudeck, Weiner and Allen-Bridson3

In 2001, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement introduced the concept of a “bundle”: a set of evidence-based interventions that, when implemented together, improve patient outcomes when compared with individually implemented interventions.4 Central venous catheter (CVC) maintenance bundles are associated with decreased CLABSI rates in children.Reference Choi, Chang and Hanauer5-Reference Costello, Morrow, Graham, Potter-Bynoe, Sandora and Laussen13 Bundle elements include discussing the CVC need daily, limiting CVC entries, disinfecting needleless connectors, changing the CVC dressing every 7 days, and replacing needleless connectors and administration sets per hospital policy.Reference Marschall, Mermel and Fakih14-16 Furuya et alReference Furuya, Dick, Perencevich, Pogorzelska, Goldmann and Stone17 demonstrated ICUs that monitored bundle adherence and maintained ≥95% compliance had significantly lower CLABSI rates. In pediatric patients, attaining high adherence with a CVC maintenance bundle presents a continued challenge.Reference Duffy, Rodgers, Shever and Hockenberry6,Reference Rinke, Chen and Bundy12,Reference Affolter, Huskins, Moss, Kuhn, Gedeit and Rice18,Reference Fisher, Cochran and Provost19 Previously published studies have not described sustained CVC maintenance bundle reliability in a children’s hospital.

Kamishibai cards (K-cards) are tools that provide scripting for interactions between clinicians and auditors. The concept originated as a form of storytelling in Japanese Buddhist temples, and Toyota has used it as a management tool for auditing.Reference Iwao20 K-cards minimize differences between auditors in style and attention to detail; this standardization reduces variability in outcomes for audits conducted by different people. Jurecko et alReference Jurecko21 reported an association between hospital K-card use and increased bundle adherence. Shea et alReference Shea, Smith, Koffarnus, Knobloch and Safdar22 found K-card interactions beneficial for reminding unit leaders and frontline nurses about bundle elements. Many institutions have adopted K-cards for monitoring adherence for healthcare-associated infection prevention, but published data demonstrating the impact on outcomes are limited.

The aims of this quality improvement (QI) initiative were to implement hospital-wide CVC K-card audits and to evaluate their impact on maintenance bundle reliability and CLABSI rates.

Methods

Setting and population

This QI initiative was implemented at a 415-bed academic pediatric hospital with 25,000 annual inpatient admissions. The intervention was implemented in 4 intensive care units, 1 intermediate care unit, 3 medical units, 2 oncology units, 1 cardiology unit, and 3 surgical units. The infection prevention and control (IPC) program at this institution includes 7 infection preventionists, a data analyst, and 2 physician medical directors. Each inpatient unit has a unit-based nurse with protected time for infection prevention activities. All inpatients with a CVC in place for ≥1 day(s) between November 1, 2017, and October 31, 2018, were eligible for inclusion. Inpatients with only dialysis and/or pheresis catheters were excluded because bedside nurses who participated in K-card rounds are not responsible for the daily maintenance of these specialized catheters. Results are reported using Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) version 2.0 guidelines as a framework.Reference Ogrinc, Davies, Goodman, Batalden, Davidoff and Stevens23

Intervention

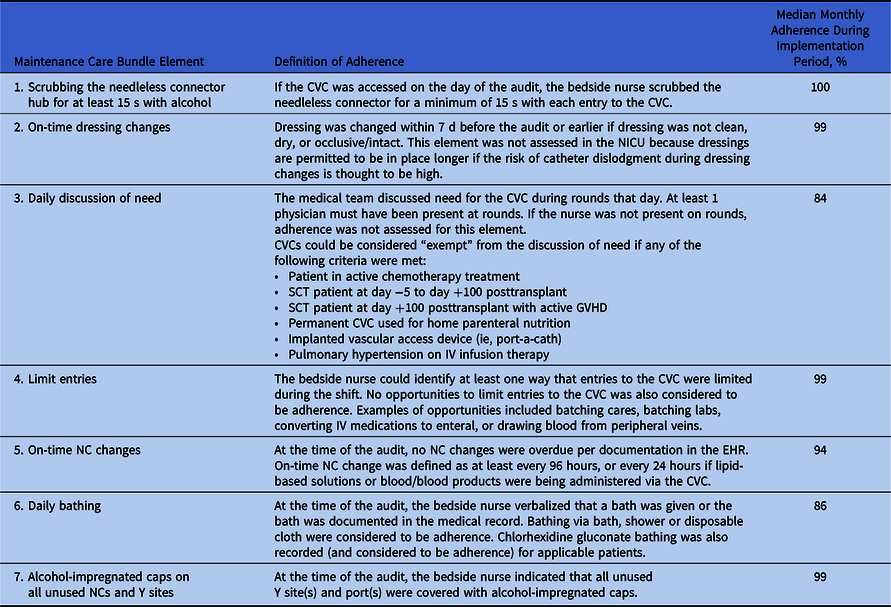

Infection preventionists developed a CVC K-card with interdisciplinary input (Supplemental Fig. 1 online). Because maintenance bundle reliability is the main driver of CLABSI reduction in pediatric ICUs, these elements were the focus of the card.Reference Miller, Griswold and Harris7 The card was based on CLABSI prevention recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and other expert groups.Reference Marschall, Mermel and Fakih14,16,Reference Mermel, Allon and Bouza24,Reference Bell and O’Grady25 K-card audits assessed the following elements: (1) scrubbing the needleless connector hub for at least 15 seconds; (2) on-time dressing changes; (3) daily discussion of need for the CVC; (4) respondent identification of at least 1 way they limited CVC entries during their shift; (5) on-time needleless connector changes; (6) daily bathing; and (7) presence of alcohol-impregnated caps on all unused ports. Operational definitions for these elements are shown in Table 1. Before the introduction of K-cards, unit-based nurses conducted adherence monitoring using self-report audit tools, and maintenance bundle adherence averaged 94% in the 12 months prior to K-card implementation.

Fig. 1. Kamishibai card (K-card) central venous catheter (CVC) maintenance bundle overall reliability during implementation period.

Table 1. Kamishibai Card (K-Card) Maintenance Bundle Elements and Adherence

Note. CVC, central venous catheter; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; SCT, stem cell transplant; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; IV, intravenous; NC, needleless connector.

Using plan–do–study–act (PDSA) methodology, a 1-month pilot of the tool to assess feasibility and guide refinement was conducted in June 2017 in the cardiac intensive care unit (CICU), the solid-organ transplant unit, and a surgical unit. Following the pilot, feedback was obtained from stakeholders and a measurement plan was developed. On November 1, 2017, audits were expanded to all inpatient units.

Data collection

K-card audits were performed by an infection preventionist and a unit-based nursing leader. A convenience sampling approach was used to select the patients to be audited. Using the card as a guide, the auditors asked the bedside nurse a standardized series of questions and recorded feedback about the tool and general CVC maintenance. Bedside nurses reported their adherence with 5 of the bundle elements, and K-card auditors obtained information about adherence with on-time dressing and needleless connector changes through review of the electronic health record (EHR).

Audit data were recorded in REDCapReference Harris, Taylor, Thielke, Payne, Gonzalez and Conde26 and included adherence to bundle elements; the patient’s medical record number and date of birth; CVC information including the type, number of lumens, and number of days since insertion; patient receipt of parenteral nutrition, lipid-based products, or blood products in the previous 24 hours; reason(s) for nonadherence with bundle elements; and comments from the bedside nurse. Demographic data (including sex, race, ethnicity, and dates of hospital admission) for audited patients were collected retrospectively from the enterprise data warehouse (EDW).

Units with >0.3 CVC days per patient day were defined as high risk, and those with ≤0.3 CVC days per patient day were defined as low risk. High-risk areas required at least 20 audits per month, while low-risk areas required at least 10 audits per month.

Measures

The primary process measures were (1) adherence with all bundle elements and (2) adherence with each individual bundle element. Overall reliability was assessed using an “all-or-nothing” approach; if any element was not performed, the entire audit was considered nonadherent, as recommended by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement.27 To ensure accuracy, data were reviewed and cleaned monthly prior to analysis. Audit data were shared with units each month during established infection prevention committee meetings.

The primary outcome was the institution-wide CLABSI rate per 1,000 CVC days using National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) definitions.28 Our preimplementation period was November 1, 2016, to October 31, 2017, and the implementation period was November 1, 2017, to October 31, 2018. No new products or CVC policies were introduced during the implementation period. To monitor whether changes were sustained, we also defined a postimplementation “sustainability” period of November 2018–September 2019.

Analysis

Quantitative analysis

Characteristics of audited CVCs and patients were summarized using descriptive statistics. Maintenance bundle reliability was calculated monthly and expressed as a proportion. Change in reliability from the initial to final month of the implementation period was compared using χ2 tests. CLABSI rates were displayed using statistical process control charts. The change in CLABSI rate between the 12-month preimplementation period and the implementation period was assessed using Poisson regression. Analyses were performed using Stata version 13.1 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) and SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Qualitative analysis

Interviews and free-text responses from nurses were recorded and deidentified. Data were independently coded and analyzed by 2 team members (J.A.O. and J.A.C.) using established grounded-theory methods.Reference Pope, Van Royen and Baker29 Themes were generated through the constant comparison method, where new responses are compared with prior data and categories are continually developed. Initial codes were identified by line-by-line coding. These codes were placed into larger categories, ideas, and concepts. Intermediate concept codes were ultimately categorized into major themes. Saturation was reached when no new themes emerged with subsequent transcription analysis. Investigators discussed and resolved all discrepancies in concept categorization and themes.

Ethical considerations

Because this was a quality improvement initiative, our institutional review board did not review this project.

Results

Intervention modifications

Based on feedback from clinicians, the K-card was modified in February 2018 for the element regarding discussion of CVC need. During rounds, providers could indicate that a CVC was “exempt” from discussion of need if the patient met certain diagnostic criteria (Table 1).

Quantitative results

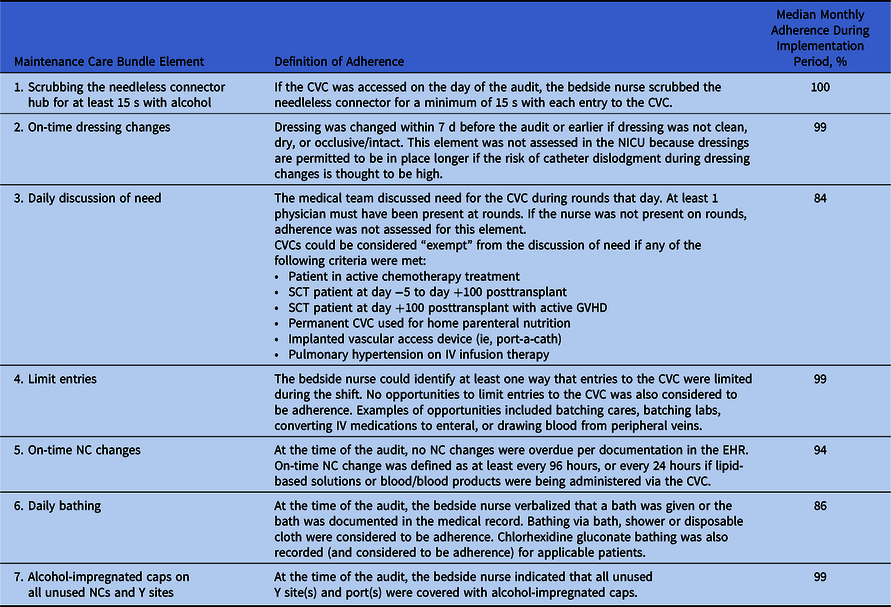

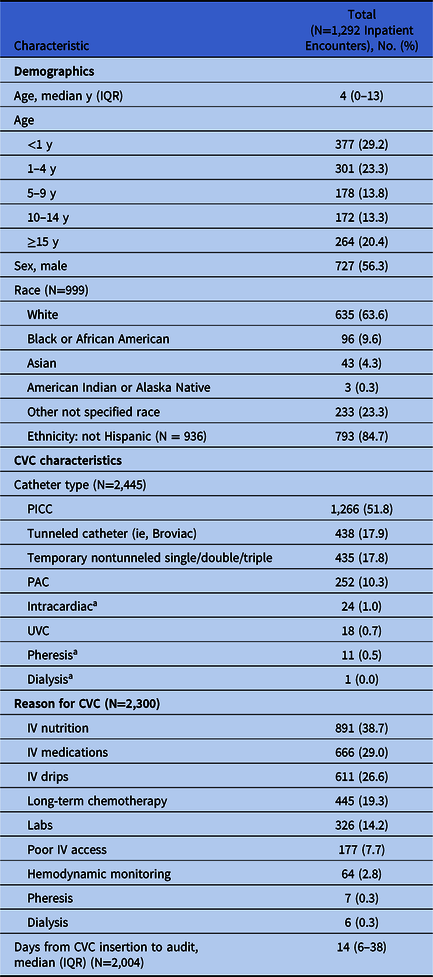

During the implementation period, 2,444 audits were performed on 1,096 patients, with an average of 204 audits per month. We removed 24 audits with missing or erroneous patient data and 99 audits with missing data for at least 1 bundle element, resulting in a final sample of 2,321 audits performed on 1,051 patients (1,292 inpatient encounters). The demographics of patients whose CVCs were audited and properties of audited CVCs are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Characteristics of Inpatient Encounters with Central Venous Catheter (CVC) Kamishibai Card (K-Card) Audits Performed Between November 1, 2017, and October 31, 2018

Note. IQR, interquartile range; PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter; PAC, implanted vascular access device; UVC, umbilical venous catheter; IV, intravenous.

a These patient encounters had an included CVC with an excluded CVC.

Figure 1 displays overall reliability for all 7 elements of the CVC maintenance bundle, which increased from 43% (80 of 188; 95% confidence interval [CI], 36%–50%) in November 2017 to 78% (183 of 235; 95% CI, 73%–83%) in October 2018 (P < .001). The most common nonadherent element was daily discussion of need for the CVC. However, reliability for this bundle element increased from 66% in November 2017 to 89% in October 2018 (P < .001). Reliability for all other individual elements either increased or stayed constant throughout the implementation period. Median monthly adherence by element during the implementation period is shown in Table 1. During our sustainability period of November 2018 to September 2019, the overall monthly reliability ranged from 73% to 81%.

Moreover, 78 CLABSIs occurred during the baseline period and 67 occurred during the implementation period. The hospital-wide CLABSI rate per 1,000 CVC days decreased from 1.35 during the baseline period to 1.17 during the implementation period, but this change was not statistically significant (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 0.87; 95% CI, 0.60–1.24; P = .41). The CLABSI standardized infection ratio (SIR) decreased by 18% during the implementation period from 1.1 to 0.9, but without statistical significance (95% CI, 0.7–1.2; P = .50). During the implementation period, the monthly CLABSI rate varied more above and below our center line, but the process never met criteria for being out of control. During the 11-month sustainability period, 50 CLABSIs were reported, and 8 of the final 9 monthly rates were below the center line, which indicates improvement in the process (Supplemental Fig. 2 online).

Monthly CVC utilization remained similar throughout the baseline and implementation period at 0.4 CVC days per patient day.

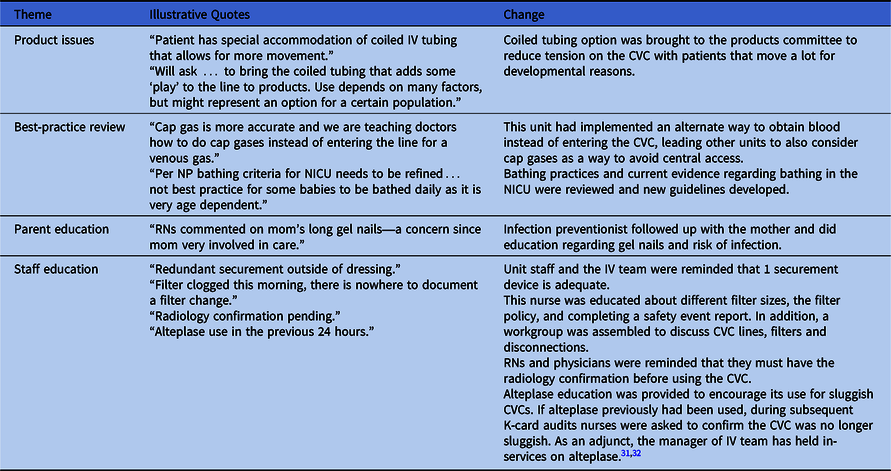

Qualitative results

During in-person conversations, nurses raised important practice and patient safety questions. We identified 4 themes from nurses’ comments at the bedside: product issues, best practice review, parent education, and staff education (Table 3). As a result of these findings, new products were tried, evidence-based reviews were conducted, and re-education of parents and staff occurred in real time.

Table 3. Qualitative Themes From Kamishibai Card (K-Card) Rounding and Associated Practices Changes

Note. CVC, central venous catheter; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; RN, registered nurse; NP, nurse practitioner; IV, intravenous;

Discussion

In our QI initiative, implementation of a standardized tool to monitor maintenance CVC care for pediatric patients increased overall reliability from 43% to 78%, and the hospital CLABSI rate trended lower after implementation. Hospitals have challenges achieving adherence to recommended maintenance care.Reference Rinke, Chen and Bundy12 Edwards et alReference Edwards, Herzig and Liu30 found that among pediatric intensive care units (PICUs) with CVC insertion and maintenance bundles, only 35% achieved ≥95% adherence over a 2-year period. Our intervention demonstrates that K-cards are a novel way to address this gap by reducing variability in audits and facilitating real-time education and dialogue with nurses about CVC maintenance in a nonthreatening environment. Hospital and unit-based leadership support enabled us to promote a culture of high reliability.

Identified opportunities for improvement included the daily discussion of need for a CVC and daily patient bathing. Barriers to daily discussion of CVC necessity included lack of provider engagement and lack of a clear guideline for this discussion. The intended goal was daily verbal acknowledgment of the CVC during rounds and a description of the need for central access. Providers argued that this discussion was unnecessary for patients who were on parenteral nutrition or who were long-term oncology patients undergoing chemotherapy through implanted ports. These patients were expected to have CVCs in place for a prolonged period, and daily discussion would extend rounds without offering a meaningful opportunity for intervention. In response to this feedback, exclusion criteria for the daily discussion were implemented in February 2018. Reliability for this element increased after this change, but it can be improved further.

Daily bathing for patients with a CVC remains another opportunity. Reported barriers to daily bathing included absence of review of bathing at hand-off or report, inconsistent bathing products across units, patient or parent preference not to bathe, and lack of knowledge regarding potential benefits of bathing for high-risk patient populations. Infection preventionists educated nurses during K-card rounding by sharing literature, by using role play to review how to address patient or parent preferences, and by obtaining alternative bathing products for particular patient populations. Our experience is consistent with the findings of Duffy et al,Reference Duffy, Rodgers, Shever and Hockenberry6 who demonstrated that the proportion of patients with documentation of a daily bath or shower increased from 30% to 70% after implementing a CVC bundle.

Our project has several limitations. We implemented a QI initiative at a large, freestanding, children’s hospital, and our experience may not be generalizable to other organizations with different patient populations. We did not attempt to account for the influence of other factors (eg, patient diagnoses, age, hospital census or staffing levels) that might affect adherence to the CVC maintenance bundle. Some bundle elements were not documented in the EHR, so adherence could not be validated by data review. Because this project was a QI initiative, it may have been underpowered to detect small differences in CLABSI rates after the intervention. The strengths of our study include prospective data collection, a long study period with many observations, and inclusion of qualitative data to describe providers’ experiences with the new process.

In summary, our QI initiative provides the first data assessing the impact of K-card rounding on outcome measures related to CLABSI prevention. We demonstrated that K-card rounding was feasible to implement and sustain in an academic pediatric hospital and was acceptable to providers. After implementation, our CVC maintenance bundle reliability increased significantly, accompanied by a trend towards a lower CLABSI rate.

Acknowledgments

None.

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2020.235