Crossref Citations

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref.

Samroodh, Mohammed

Anwar, Imran

Ahmad, Alam

Akhtar, Samreen

Bino, Ermal

and

Ali, Mohammed Ashraf

2022.

The Indirect Effect of Job Resources on Employees’ Intention to Stay: A Serial Mediation Model with Psychological Capital and Work–Life Balance as the Mediators.

Sustainability,

Vol. 15,

Issue. 1,

p.

551.

Andersone, Nelda

Nardelli, Giulia

Ipsen, Christine

and

Edwards, Kasper

2022.

Exploring Managerial Job Demands and Resources in Transition to Distance Management: A Qualitative Danish Case Study.

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health,

Vol. 20,

Issue. 1,

p.

69.

Günther, Niklas

Hauff, Sven

and

Gubernator, Philip

2022.

The joint role of HRM and leadership for teleworker well-being: An analysis during the COVID-19 pandemic.

German Journal of Human Resource Management: Zeitschrift für Personalforschung,

Vol. 36,

Issue. 3,

p.

353.

Jeske, Debora

and

Calvard, Thomas Stephen

2022.

Handbook of Research on Challenges for Human Resource Management in the COVID-19 Era.

p.

403.

Şimşek Demirbağ, Kübra

and

Demirbağ, Orkun

2022.

Who said there is no place like home? Extending the link between quantitative job demands and life satisfaction: a moderated mediation model.

Personnel Review,

Vol. 51,

Issue. 8,

p.

1922.

Jeske, Debora

2022.

Remote workers' experiences with electronic monitoring during Covid-19: implications and recommendations.

International Journal of Workplace Health Management,

Vol. 15,

Issue. 3,

p.

393.

Tapani, Annukka

Sinkkonen, Merja

Sjöblom, Kirsi

Vangrieken, Katrien

and

Mäkikangas, Anne

2022.

Experiences of Relatedness during Enforced Remote Work among Employees in Higher Education.

Challenges,

Vol. 13,

Issue. 2,

p.

55.

Park, Ju Won

Park, Seejeen

and

Cho, Yoon Jik

2023.

More isn’t always better: exploring the curvilinear effects of telework.

International Public Management Journal,

Vol. 26,

Issue. 5,

p.

744.

Wang, Qifan

Khan, Sajjad Nawaz

Sajjad, Muhammad

Sarki, Irshad Hussain

and

Yaseen, Muhammad Noman

2023.

Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Work-Related Strains and Work Engagement among Job Demand–Resource Model and Success.

Sustainability,

Vol. 15,

Issue. 5,

p.

4454.

Lenz, Lena

Hattke, Fabian

Kalucza, Janne

and

Redlbacher, Friederike

2023.

Virtual Work as a Job Demand? Work Behaviors of Public Servants during Covid-19.

Public Performance & Management Review,

Vol. 46,

Issue. 6,

p.

1382.

Li, Gang

Zheng, Qiqi

and

Xia, Mengyao

2023.

How do human resource practices help employees alleviate stress in enforced remote work during lockdown?.

International Journal of Manpower,

Vol. 44,

Issue. 2,

p.

354.

Demerouti, Evangelia

and

Bakker, Arnold B.

2023.

Job demands-resources theory in times of crises: New propositions.

Organizational Psychology Review,

Vol. 13,

Issue. 3,

p.

209.

Kwia, Josiah

2023.

Organizational Behavior.

p.

1.

Buonomo, Ilaria

Ferrara, Bruna

Pansini, Martina

and

Benevene, Paula

2023.

Job Satisfaction and Perceived Structural Support in Remote Working Conditions—The Role of a Sense of Community at Work.

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health,

Vol. 20,

Issue. 13,

p.

6205.

AL, Begüm

2023.

Culture, Motivation, and Performance: Remote and Workplace Dynamics in Organizations.

OPUS Journal of Society Research,

AlZgool, Mahmoud

AlMaamari, Qais

Mozammel, Soleman

Ali, Hyder

and

Imroz, Sohel M.

2023.

Abusive Supervision and Individual, Organizational Citizenship Behaviour: Exploring the Mediating Effect of Employee Well-Being in the Hospitality Sector.

Sustainability,

Vol. 15,

Issue. 4,

p.

2903.

Chowhan, James

and

Pike, Kelly

2023.

Workload, work–life interface, stress, job satisfaction and job performance: a job demand–resource model study during COVID-19.

International Journal of Manpower,

Vol. 44,

Issue. 4,

p.

653.

Bhattcharjee, Amitabh

Chakraborty, Shreyashi

and

Elembilassery, Varun

2024.

Enforced work-from-home and its impact on psychological conditions: a qualitative investigation in India.

Journal of Asia Business Studies,

Vol. 18,

Issue. 5,

p.

1408.

Wei, Zuolin

Xia, Bocheng

Jiang, Lingli

Zhu, Huaiyi

Li, Lingyan

Wang, Lin

Zhao, Jun

Fan, Ruoxin

Wang, Peng

and

Huang, Mingjin

2024.

Factors affecting occupational burnout in medical staff: a path analysis based on the job demands-resources perspective.

Frontiers in Psychiatry,

Vol. 15,

Issue. ,

Schellaert, Maaike

and

Derous, Eva

2024.

Retirement decisions in times of COVID-19: the role of telework, ICT-related strain and social support on older workers’ intentions to continue working.

Personnel Review,

Vol. 53,

Issue. 8,

p.

1950.

Rudolph etal. (Reference Rudolph, Allan, Clark, Hertel, Hirschi, Kunze, Shockley, Shoss, Sonnentag and Zacher2021) highlight 10 areas of industrial-organizational (I-O) psychology that are relevant to the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on work. They also briefly describe the prototypical media headlines that highlight these different topics. Indeed, since the beginning of the pandemic, many popular press articles have been written on how managers and organizations should handle and address a multitude of changes brought on by COVID-19. Although these articles offer a host of practical recommendations, they often lack a theoretical foundation that would provide decision makers with greater understanding of why certain recommendations might be effective. Without an explanation of why recommendations might work, managers might feel uncertain as to which recommendations to try, and if they find that a recommendation does not apply to their context, they might dismiss the suggestions completely. The current work extends etal.’s focal article by focusing on telecommuting and the job demands-resources (JD-R) model (Demerouti etal., Reference Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner and Schaufeli2001), using job demands and resources to provide a framework that underlies the many recommendations provided for managers and organizations during COVID-19. By providing this framework, we hope to empower decision makers to better adapt existing recommendations to their unique work contexts in order to maintain employee well-being and performance while telecommuting.

Telecommuting during COVID-19 and the JD-R model

Previous research has demonstrated that telecommuting can positively affect employee well-being when it provides employees with greater flexibility, reduces the stress and time costs of commuting, increases employee productivity, and allows employees to better balance their home and work lives (for a review of the benefits of telecommuting, see Mann & Holdsworth, Reference Mann and Holdsworth2003). However, telecommuting can also result in a greater intensification of work and a decreased ability to “switch off” from work (Felstead & Henseke, Reference Felstead and Henseke2017), and evidence for beneficial outcomes tends to come from individuals who chose to telecommute and were able to effectively create work–life boundaries (e.g., Greer & Payne, Reference Greer and Payne2014; Montreuil & Lippel, Reference Montreuil and Lippel2003). In contrast, the COVID-19 crisis did not give employees the choice to telecommute; rather, it triggered a forced transition to telecommuting for many. The volatility and uncertainty caused by this pandemic has engendered enormous strain for workers, with one survey finding that 69% of workers regard COVID-19 as the most significant stressor in the entirety of their careers (Ginger, 2020). It has rapidly changed the workplace environment by blurring the boundaries between work and home life, subsequently exacerbating work–family conflict and jeopardizing work–life balance for many employees (Knight etal., Reference Knight, Parker and Keller2020). This multipronged threat has also heightened employees’ social isolation, making it increasingly difficult for them to access instrumental and emotional support from coworkers and organizational leaders.

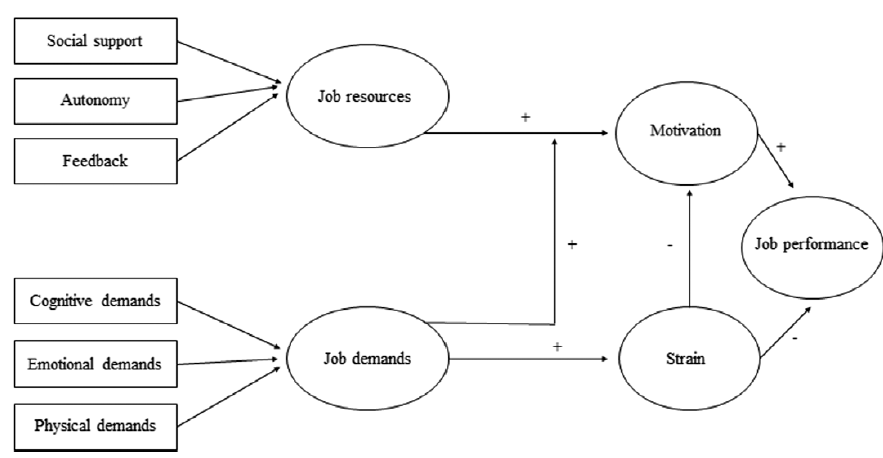

Organizational psychologists have identified employee well-being as a vital work outcome, one that is highly influenced by individual and organizational factors such as feedback, autonomy, and emotional demands. These characteristics of individuals and their jobs are often grouped into two broad categories, namely job demands and resources, which are associated with employee motivation and strain and ultimately contribute to job performance (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2017; see Figure 1). The literature’s current conceptualization of the JD-R model (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2017) also incorporates personal resources, as well as actions that employees take based on their job demands and resources (e.g., job crafting, self-undermining). However, in this paper we specifically focus on job demands and resources in an attempt to highlight the role of managers and organizational leaders. Job demands refer to the physical, social, or organizational characteristics of the work itself (e.g., role overload, ambiguity, time pressure) that require prolonged physical and/or mental effort by employees and are subsequently associated with significant decrements in employee health and performance over time. Job resources (e.g., job control, supervisor support, feedback) are the physical, psychological, social, or organizational facets of work that help galvanize employees toward achieving work goals and reduce the physiological and psychological consequences of heightened job demands. In the following sections, we discuss a comprehensive (but nonexhaustive) list of job demands and resources, adapted from Bakker and Demerouti (Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007) and Xanthopoulou etal. (Reference Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Demerouti and Schaufeli2007), to help provide a clearer framework of how organizations and their leaders can improve telecommuter well-being. Each demand and resource is outlined in addition to how it is influenced by telecommuting and examples of how organizations can adjust these demands and resources. These examples are not necessarily one-size-fits-all solutions; rather, organizations should apply what they know about their employees and needs in order to adapt and create practices that work for them.

Figure 1. Adapted JD-R Model and Employee Well-Being.

Note. Adapted from Bakker & Demerouti (Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2017).

Reducing job demands

A reduction in job demands might sound daunting to an organization that is focused now, more than ever, on preserving the bottom line. However, reducing job demands does not mean lowering quality or production standards—in fact, reducing unnecessary cognitive, emotional, and physical job demands should improve employee well-being and therefore positively affect organizational outcomes.

Cognitive demands

Although a certain degree of cognitive demands are inherent in any job, there can be additional cognitive demands placed on employees during COVID-19 that are not directly task related. For example, transitioning to telecommuting may create some role ambiguity and conflict if employees are unsure about how to adapt to the decreased boundaries between work and life or have increasing caretaking demands at home. Employees may also be thinking about their personal and loved ones’ health during COVID-19 as well as their job security during these precarious times. There are all stressors that may increase employees’ cognitive demands and make it harder for them to focus on their job tasks. One way that organizations and managers can help reduce employees’ cognitive demands during this time is by maintaining transparency and reducing role ambiguity and conflict. Both role ambiguity, defined as a lack of information or unclear information about a given worker’s job or expectations, and role conflict, defined as an individual’s experience of incompatible demands from the different roles they have (e.g., employee and parent), have been consistently associated with decreased job satisfaction and commitment, as well as increased mental health issues (e.g., depression, anxiety; Fisher & Gitelson, Reference Fisher and Gitelson1983; Tubre & Collins, Reference Tubre and Collins2000). As a result, it is important for managers to be as transparent and clear as possible when communicating with their teams about how project timelines, priorities, and tasks may be affected during this time. For example, managers can make clear what projects and tasks are most critical during each meeting so that employees are cognizant of what they should be focusing on—and what tasks they can potentially delay if they have other responsibilities come up at home. Managers should also set expectations on how team members will keep each other updated (e.g., virtual meetings versus emails, frequency of contact) and how the team plans to adjust to potential changes.

Emotional demands

Employees are likely also experiencing many emotions during this time; however, they may feel pressure to only present positive emotions at work (e.g., during virtual meetings) in order to create a good impression or a positive work environment for others. Research has demonstrated that emotions often spill over work–life boundaries (e.g., Sanz-Vergel etal., Reference Sanz-Vergel, Rodríguez-Muñoz, Bakker and Demerouti2012), and when telecommuting, it may become even harder to prevent this spillover as the boundaries between work and life are blurred. Employees may engage in surface acting (i.e., displaying a fake emotion without changing the felt emotion) in an attempt to hide some of their negative emotions, but this acting can lead to increased stress, work withdrawal, and burnout (Grandey, Reference Grandey2003). In addition to creating negative effects for the individual, hiding these emotions can create the false impression that everyone is doing fine and can further isolate employees who feel like they are struggling. However, research has also shown how a climate of authenticity (i.e., acceptance and respect for individuals’ felt emotions) can buffer some of these negative outcomes (Grandey etal., Reference Grandey, Foo, Groth and Goodwin2012). Managers and coworkers can regularly check in on a personal level, encouraging each other to express their authentic emotions instead of simply focusing on tasks that need to be completed. Managers can also help set an example by discussing some of their authentic emotions and how they have been coping in order to normalize these conversations and destigmatize mental well-being issues so that their employees feel comfortable seeking help if needed.

Physical demands

Telecommuters also may not have as many natural breaks built into the day (e.g., walking to a meeting, chatting with coworkers). This is an important concern because employees will be more likely to burn out if they are constantly working, and breaks have been shown to help reduce stress and increase work engagement (Hu etal., Reference Hu, Chen and Cheng2016; Kühnel etal., Reference Kühnel, Zacher, De Bloom and Bledow2017). To compensate for this lack of built-in breaks, managers should encourage their employees to be intentional about taking breaks throughout the workday and avoid scheduling multiple back-to-back meetings. In addition, now that employees have fewer boundaries between work and home, managers should remind their team members that they do not need to expand their work hours and work during nonwork hours (e.g., early morning, late evening) because this can have negative effects on employees’ recovery processes, resulting in worse mood and increased cortisol levels (Dettmers etal., Reference Dettmers, Vahle-Hinz, Bamberg, Friedrich and Keller2016). Managers should also be cognizant of when they send work emails and avoid sending them during nonwork hours, instead delaying the email or using a service that allows for scheduled emails. This can help relieve pressure from employees to feel like they constantly need to be working now that they are telecommuting.

Increasing job resources

Job resources do not need to cost organizations much money, if they cost anything at all, but increasing these resources can have dramatic payoffs in terms of employee well-being and mental health. This section expands on the resources of social support, autonomy, and feedback.

Social support

Extensive research has demonstrated the positive effects of social relationships on mental and physical health (e.g., Cohen, Reference Cohen2004). Feeling a sense of support at work can have many benefits for workers, such as buffering the negative effects of work stress and work–family conflict (Etzion, Reference Etzion1984; Kossek etal., Reference Kossek, Pichler, Bodner and Hammer2011). Providing social support at work may be especially important during this time because employees may be more isolated from their normal sources of support (e.g., friends, family) or relationships with these sources may be shifting (e.g., increased amount of time spent with family or other housemates). Managers can set an understanding and empathetic tone by being flexible about their expectations for how their team will work together and accomplish tasks during this time. They can also hold regular virtual office hours or set an open-door policy so that team members have a way to reach out about any questions or concerns. In addition, as managers check in with employees, they can acknowledge that individual employees may be contending with these changes in different ways and work with them to develop a plan that takes caregiving or other home obligations into account such as flexible meeting times, shorter meetings, or even doing away with unnecessary meetings altogether. However, managers may not know what type of support their employees could benefit from, so they can use a needs analysis approach to discern what might be helpful. In this context, a needs analysis need not be formal or include statistics at all—a series of conversations with employees and/or an anonymous survey could shed light on what employees are struggling with and better inform managers as to which kinds of support would be most helpful.

Managers can also encourage social interactions among team members to maintain team cohesion and provide an additional sense of social support. As many employees will likely be dealing with a variety of challenges, it may be beneficial not only to process those experiences with others but also to help others realize they are not alone. Managers can block out time in virtual team meetings for employees who are comfortable with sharing to talk about their life updates; this may also increase empathy and understanding among team members about why another team member may be less responsive or attentive than usual.

Autonomy

The many demands of working and living during the COVID-19 pandemic can feel like a loss of control and autonomy. Although this may seem like an occasion for increased employee monitoring to ensure that employees are getting their work completed, these efforts may have a negative effect because they further reduce employees’ sense of autonomy. Instead, increasing employee autonomy can enable them to be more engaged and thus more productive (De Spiegelaere etal., Reference De Spiegelaere, Van Gyes and Van Hootegem2016). For example, for employees who may be preoccupied during typical working hours due to taking care of children or other family members, managers can brainstorm different ways to keep these employees engaged (e.g., recording and posting meetings, getting the employee’s thoughts before a meeting and sharing them with others if the employee is unable to attend). Managers can also suggest virtual “working meetings” where team members can independently set aside times to work on projects together outside of the regular check-in meetings if any employees need help setting a routine or maintaining accountability with others. This way, managers can provide a foundation for team members’ work schedules but ultimately allow the individuals to decide what works best for them.

Feedback

Although managers may not see their employees as often while they are telecommuting, it is important to still check in regularly and provide feedback on how their employees are doing. Due to the abrupt nature of this transition to telecommuting, employees may not be certain about whether they are performing in an adequate manner, especially because typical avenues for more informal feedback may be missing (e.g., discussing how a meeting went on the walk back from a conference room or the drive back from a client site). Providing feedback in an accurate but sensitive manner can alleviate some of these concerns as well as improve job satisfaction and performance (Demerouti etal., Reference Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner and Schaufeli2001; Kim & Hamner, Reference Kim and Hamner1976). In addition, this feedback can help clarify what tasks or projects employees should be prioritizing, especially given that they may have more limited resources now from increased responsibilities at home, fewer work–life boundaries, and so on. It is also important to ask for feedback from employees and inquire as to whether there is anything that the manager or organization could be doing better to aid employees during this time. This provides employees with a sense of voice (i.e., feeling like one has the opportunity to challenge or influence a process or outcome at work), which has been shown to have positive effects on employee engagement, commitment, and performance (e.g., Ng & Feldman, Reference Ng and Feldman2012).

Conclusion

Organizations, managers, and employees have likely been inundated with lists of suggestions on how to effectively adapt to telecommuting during the COVID-19 pandemic, but these lists are not always evidence based and may be difficult to navigate. Additionally, not all suggestions apply to each situation, and as a result it is helpful to understand not only what the recommendations are but also why a particular recommendation works. The JD-R model provides this why, enabling decision makers to better understand which recommendations may help them decrease the job demands and increase the job resources of their workplaces so that their employees can work more productively and maintain their personal well-being. Although the demands and resources provided here are not exhaustive, they attempt to clarify that current occupational stress theories like the JD-R model can cut through the noise to steer organizational leaders toward ideas that are rooted in decades of scholarship.