Introduction

The frequently discussed academic–practice gap (i.e., the divergence between research findings and organizational practices; Bartunek & Rynes, Reference Bartunek and Rynes2014; Rogelberg et al., Reference Rogelberg, King and Alonso2022; Tkachenko et al., Reference Tkachenko, Hahn and Peterson2017) within industrial-organizational (I-O) psychology and other business disciplines is an ever-pervasive issue that limits the utility of research for solving pressing organizational issues. For the field of I-O psychology to overcome the academic–practice gap and have a positive impact on society, we (i.e., I-O psychology academics and practitioners) argue that I-O psychologists must do a better job collaborating with diverse stakeholders who can provide immense value to and also benefit from our research. Specifically, we advocate for an increase in a particular form of collaboration—engaged scholarship—which represents a method of collaborative research that involves seeking and incorporating multiple stakeholder perspectives into the design of research on complex problems (Van de Ven, Reference Van de Ven2007). These stakeholders can provide unique insights during the research process, thus enhancing the collective understanding of the issues at hand and the quality and relevance of the research. This group can include researchers from other disciplines, practitioners who are working with organizations, frontline managers of the target population, and leaders of the organizations being studied. A diverse research team can help ensure adoption of the project, sponsorship of initiatives, representation of unique perspectives or connection to the problem, and availability of resources. The primary goal of this article is to continue the conversation about the potential benefits of engaged scholarship for not only maintaining but also enhancing the relevance of I-O psychology to society. In doing so, we also aim to provide two additional noteworthy contributions to this discussion.

First, this article provides an empirical snapshot of the current prevalence of inclusive collaborations by quantifying nonacademic authorship of articles across a range of different I-O psychology-related journals. The number of nonacademic authors of journal articles provides a quantifiable indicator that other stakeholders are involved in the production of research and addresses a feature of the academic–practice gap not addressed in many past conceptual articles (Bartunek & Rynes, Reference Bartunek and Rynes2014). Second, throughout this article, we provide an integrated perspective from both practitioners and academics on the academic–practice gap within I-O psychology and the role that collaborations can have in reducing it. The often-unheard voice of practitioners is critical as nearly every paper written on the gap has been produced by academics (Geimer et al., Reference Geimer, Landers and Solberg2020; Kaufman, Reference Kaufman2022; Rotolo & Allen, Reference Rotolo and Allen2022; Van de Ven, Reference Van de Ven2007; but see Vosburgh, Reference Vosburgh2022). Although many useful insights have been derived from such articles, we believe an integrated perspective that includes practitioners is vital to include in these conversations (see Lawler & Benson, Reference Lawler and Benson2022). Practitioners can foster meaningful advances to I-O psychology research and practice via engaged scholarship and can provide new insights into how to best address I-O psychology’s academic–practice gap, especially through collaborative research. Although numerous recommendations on how to reduce the academic–practice gap have been made, many of these focus on building experiences that allow individuals to succeed in both roles (e.g., organizational sabbaticals for academics), which is impractical. Our paper outlines how academics and practitioners can work together to incorporate the principles of engaged scholarship into the research process through hard-won advice from the collaborative research experiences of our authors, who include both I-O academics and practitioners.

In sum, our goals of this paper are to (a) provide initial empirical evidence on the status of research collaborations within the field of I-O psychology; (b) provide firsthand insights (based on the rich and unique experiences of many of the authors of this paper) about the benefits of engaged scholarship to I-O psychology, how to encourage its practice, and guidelines for instilling engaged scholarship throughout the research process; and (c) offer a call to action consisting of practical recommendations for reducing the academic–practice gap and enhancing the relevance of I-O psychology to society via engaged scholarship. In doing so, we hope this article helps advance our understanding of the I-O academic–practice gap and how to close it, promotes a fruitful conversation about research collaborations, and inspires action on how to ensure the relevance of I-O psychology to society.

The academic–practice gap

An important goal of our profession is the dissemination of research and evidence-based I-O best practices. Unfortunately, well-established and useful I-O research findings are often not translated into practice (Simsek et al., Reference Simsek, Li and Huang2022) for various reasons (e.g., lack of reward, lack of access, see below for details). In other cases, I-O research findings are not directly applicable to actual organizational problems and/or needs. This decades-long problem of the academic–practice gap persists for a myriad of reasons (Rynes, Reference Rynes and Kozlowski2012) and is not unique to our field (e.g., ecology, see Bertuol-Garcia et al., Reference Bertuol-Garcia, Morsello and El-Hani2018; social work, see Steens et al., Reference Steens, Van Regenmortel and Hermans2018; education, see Rycroft-Smith, Reference Rycroft-Smith2022; accounting, see Blochm et al., Reference Blochm, Kleinman and Peterson2017).

When examining why practical implications of evidence-based research (typically included at the end of journal articles) are so infrequently transferred from academia into practice, many reasons on both I-O academic and practitioner sides exist. Practitioners cite that, often, practical implications of research are too broad (i.e., stated too generally to be useful; Bleijenbergh et al., Reference Bleijenbergh, van Mierlo and Bondarouk2021), hard to interpret (Keiser & Leiner, Reference Keiser and Leiner2009), or irrelevant (Nicolai & Seidl, Reference Nicolai and Seidl2010), whereas academics state that practitioners rarely read academic journals (Rogelberg et al., Reference Rogelberg, King and Alonso2022) or that the “knowing–doing gap” (i.e., challenges in translating knowledge into tangible actions) is at play (Pfeffer & Sutton, Reference Pfeffer and Sutton2000). Additionally, many practitioners favor reaching out to other practitioners for practical issues (Rynes et al., Reference Rynes, Colbert and Brown2002), and scientific jargon paired with a lack of access to peer-reviewed articles often creates a barrier between academics and practitioners (Simón & Ferreiro, Reference Simón and Ferreiro2018). These barriers in our own field are important to address for us to effectively convey the benefits of I-O psychology to society. Part of our training as I-O psychologists is to think creatively to investigate and understand work phenomena, overcome barriers, and develop practical solutions. Engaged scholarship is a creative approach for overcoming some of these hurdles via a collaborative research process that allows for the co-production of knowledge that is beneficial for all parties involved.

Empirical evidence for collaboration

To set the stage for our discussion, we first sought to determine the current state of research collaborations within I-O psychology. One way we as a field can evaluate the current status of academic–practitioner collaboration is to examine how frequently I-O publications contain authors from nonacademic backgrounds. Although this method does not address all kinds of collaboration, it does provide a tangible metric for the level of collaborations between practitioners and academics. To this end, we explore the frequency of academic–practitioner collaborations in various I-O journals during a recent 6-year period.

We examined the number of articles that included nonacademic authors within 14 I-O psychology-related journals from 2018 to 2023. This range focuses on the current state of the field and provides insights into the present status of research collaborations. This is also a period where there have been significant shifts in the workplace landscape that have attracted increased attention from I-O psychology researchers and practitioners. These include the rise of remote work (e.g., Perry et al., Reference Perry, Rubino and Hunter2018); advancements in AI and automation (e.g., Cascio & Montealegre, Reference Cascio and Montealegre2016; Chamorro-Premuzic et al., Reference Chamorro-Premuzic, Winsborough, Sherman and Hogan2016); demographic shifts toward a multigenerational workforce; the importance of diversity, equity, and inclusion in workplace culture (e.g., Myers, Reference Myers2016); and the expanding gig economy (e.g., Kuhn, Reference Kuhn2016). These challenges and opportunities can undoubtedly benefit from enhanced research collaborations, and so understanding the extent to which collaborations are helping to address pressing issues is especially useful.

Journals were selected as a representative sample of important I-O psychology journals across varying levels of prestige (see Highhouse et al., Reference Highhouse, Zickar and Melick2020) and impact. Journals were also selected to represent a mixture of empirical, review or conceptual, and popular press article types (see Carton & Mouricou, Reference Carton and Mouricou2017 for a conceptually similar approach and rationale). Note that it is not possible to examine every journal and that the exclusion of any particular journal in this analysis is not meant to imply that it is not important or relevant. At some point, the scope of analysis needed to be limited, and thus we opted to limit our review to 14 key journals that would be of interest to either academics and/or practitioners. Of these journals, nine were primarily empirical (International Journal of Selection and Assessment [IJSA], Journal of Applied Psychology [JAP], Journal of Business and Psychology [JBP], Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology [JOOP], Organizational Research Methods [ORM], Personnel Assessment and Decisions [PAD], Personnel Psychology [PP], Work & Stress [WS], Journal of Occupational Health Psychology [JOHP]), three were primarily review or conceptual (Industrial and Organizational Psychology [IOP], Organizational Psychology Review [OPR], Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior [AROPOB]) and two were popular press, practitioner-oriented sources (Harvard Business Review [HBR], MIT Sloan Management Review [MITSMR]).

Different article types (i.e., empirical, conceptual, review, popular press) were included for comparative purposes to determine if different kinds of outlets include differing numbers of nonacademic authors compared to others. We recognize and acknowledge that some of the journals considered primarily empirical do occasionally contain nonempirical articles. This distinction in journal types is mainly to distinguish these journals from those that are clearly review or conceptual and practitioner oriented and is not meant to imply that the journals we considered “primarily empirical” contain exclusively empirical articles (hence use of the term “primarily”). Moreover, the inclusion of multiple article types helps ensure that different forms of collaboration are represented (e.g., articles reporting research that was empirically conducted, articles summarizing the current state of research in a given area, articles making a research-based conceptual argument, and so forth). In conclusion, the journals selected for inclusion were not necessarily meant to be exhaustive but instead representative of some of the most interesting and applicable journals to I-O psychology.

To determine the number of articles with nonacademic authors, the first, second, and third authors of this focal article first reviewed all articles within each journal and coded the number of articles that listed at least one nonacademic author affiliation. We chose to treat this as a binary variable rather than focusing on the number of nonacademic authors per se, because collaborations are not contingent on the number of stakeholders engaged in collaborative research. That is, if one article has one nonacademic author and another has three, both can still be indicative of collaboration. A nonacademic author was defined as an individual whose primary affiliation was not an academic university (i.e., their affiliation was a company, government agency, or some other nonuniversity entity). Ambiguous cases were reviewed by the three authors who completed the coding and resolved via consensus discussions. Several unique article types were not included in our review (e.g., editorials, list of awardees, reviewer acknowledgments, book reviews, errata, corrigenda) due to misalignment with the goal of this analysis and potential to misrepresent results. A few journals required additional consideration about what article types to review and include. For example, HBR and MITSMR have many different section types, with only some of them being relevant to the current study. Given this, we only examined the articles in the “Features” section of HBR and the “Research Feature” and “Research Highlight” sections of MITSMR because these were best aligned with the goal of the current study. Likewise, although IOP contains both focal articles and commentaries, we choose to examine only the focal articles for this study. Based on these considerations, a total of 2,771 articles were identified, reviewed, and coded across 14 different journals from 2018 to 2023.

Results and discussion

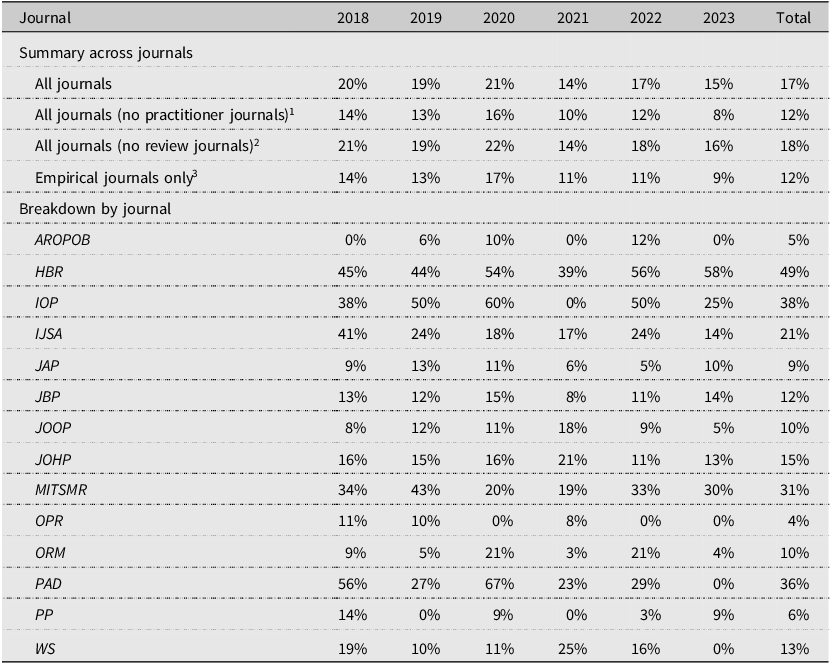

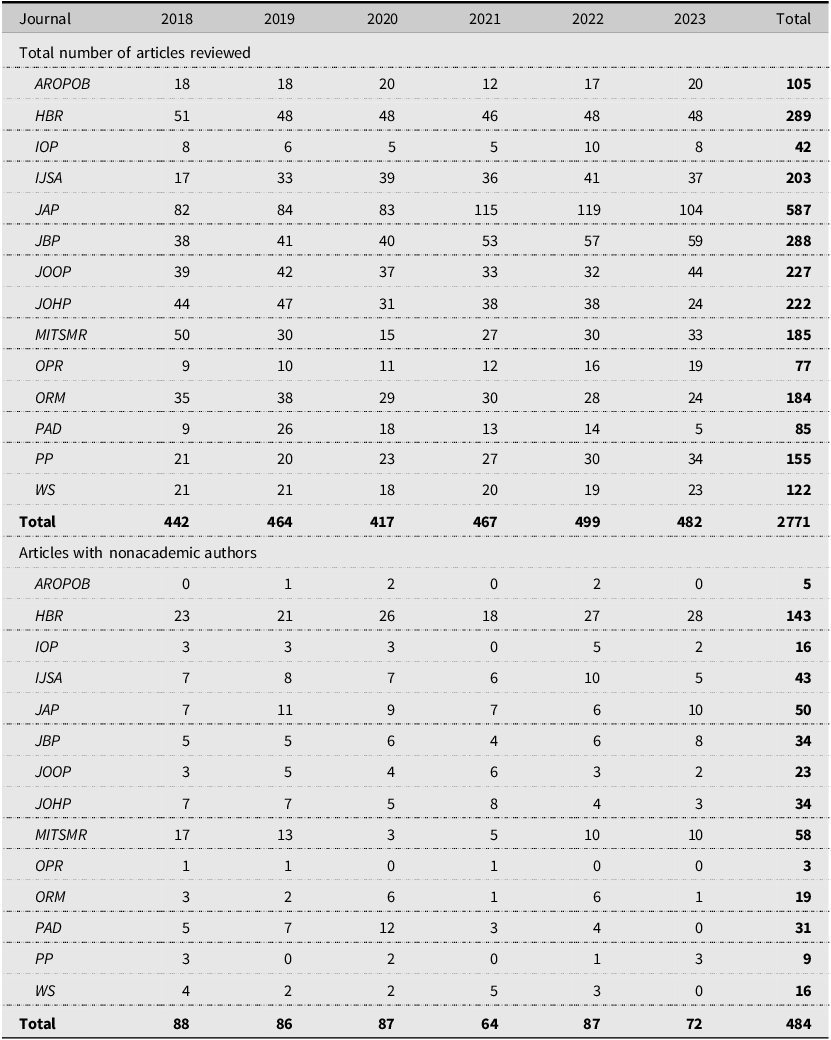

The results of this review are summarized in Table 1 (which reports percentages) and Table 2 (which reports counts to help better contextualize the findings). Across all 2,771 articles for the 14 journals reviewed from 2018 to 2023, 17% (484 out of 2,771) contained at least one nonacademic author (note that we can only state the number of nonacademic authors and are unable to infer details about the categorization of these nonacademics, such as whether they are an I-O or non-I-O practitioner). As Table 1 and 2 indicate, these results varied considerably by journal. For example, the journal with the highest percentage of nonacademic authors was HBR, a practitioner-oriented journal (49%; 143 out of 289), and IOP, a conceptual journal aimed at both academics and practitioners (38%; 16 out of 42). PAD, a primarily empirical journal, had the third highest percentage of nonacademic authors (36%; 31 out of 85). The journals with the lowest percentage of nonacademic authors were OPR (4%; 3 out of 77), AROPOB (5%; 5 out of 105), and PP (6%; 9 out of 155), with the first two being review journals and the latter being primarily empirical. When examining only the primarily empirical academic journals (n = 9), the percentage of articles with at least one nonacademic author slightly decreased to 12% (259 out of 2073); though, as seen in Table 1, most of this decrease is driven by the exclusion of the practitioner-oriented journals, not the conceptual and review journals.

Table 1. Percent of Articles From Industrial-Organizational Psychology Journals With at Least One Nonacademic Author

Note. 1Did not include HBR or MITSMR. 2Did not include AROPOB, IOP, or OPR. 3Did not include HBR, MITSMR, AROPOB, IOP, or OPR. AROPOB = Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, HBR = Harvard Business Review, IOP = Industrial and Organizational Psychology, IJSA = International Journal of Selection and Assessment, JAP = Journal of Applied Psychology, JBP = Journal of Business and Psychology, JOOP = Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, JOHP = Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, MITSMR – Massachusetts Institute of Technology Sloan Management Review, OPR = Organizational Psychology Review, ORM = Organizational Research Methods, PAD = Personnel Assessment and Decisions, PP = Personnel Psychology, WS = Work and Stress. Only articles in the “Features” section of HBR, articles in the “Research Features” and “Research Highlights” sections of MITSMR, and focal articles within IOP were reviewed and coded. Several other article types (e.g., editorials, book reviews) were also excluded across journals due to not aligning with the goal of this study. Percentages are rounded for ease of interpretation. The percentages were computed based on the counts of articles. Due to rounding, the percentages in this table may not average to the total percentage values listed in the top rows and column on the far right.

Table 2. Count of Articles From Industrial-Organizational Psychology Journals With at Least One Nonacademic Author

Note. AROPOB = Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, HBR = Harvard Business Review, IOP = Industrial and Organizational Psychology, IJSA = International Journal of Selection and Assessment, JAP = Journal of Applied Psychology, JBP = Journal of Business and Psychology, JOOP = Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, JOHP = Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, MITSMR – Massachusetts Institute of Technology Sloan Management Review, OPR = Organizational Psychology Review, ORM = Organizational Research Methods, PAD = Personnel Assessment and Decisions, PP = Personnel Psychology, WS = Work and Stress.

Overall, from the 14 journals examined, nearly one in five articles (17%) showed evidence of research collaboration through nonacademic authorship, though this is closer to 1 in 10 when practitioner and review journals are excluded (12%). It should again be acknowledged that these results vary considerably across journals and, as noted below, likely represent an optimistic estimate. Not too surprisingly, the practitioner-oriented journals (e.g., HBR and MITSMR), and those that explicitly target both audiences (e.g., IOP) or emphasize practical significance (e.g., PAD), tended to have the most articles with nonacademic authors. Conversely, the review-based journals (e.g., OPR), as well as I-O psychology’s “flagship” journals (e.g., JAP, PP) had the lowest number of nonacademic authors.Footnote 1

One limitation of this analysis is that the quality and depth of collaborations cannot be directly determined from the present results. For example, although APA guidelines state that all coauthors must have made a significant scientific contribution to the work (American Psychological Association, 2020), a nonacademic author might be listed only because they provided data access. Such a situation would not align with the goal of collaborative research, which views organizations as more than mere data collections sites, and nor would it necessarily align with APA authorship guidelines (though this latter issue is beyond our control). Determining and verifying the level of collaboration for each article would likely require a much more comprehensive analysis and a different research design. Nonetheless, for purposes of this review, we generally assumed that all authors listed for an article were involved in the research process to some extent (which we view as a reasonable assumption) and that the presence of academic and nonacademic authors for a given article is indicative of some form of research collaboration.

It should also be acknowledged that the percentage of nonacademic authors may be overestimated as many of them could be new graduates who conducted the research while still students. That is, when the project was completed, the students were not affiliated with a university and therefore listed a different affiliation despite the research being conducted in the past while at an academic institution.

Last, we acknowledge that we only examined 14 possible journals for this analysis. Although we attempted to select a wide range of journals with different emphases and impact, it might be beneficial for future research to examine a wider range of journals (though we expect the results will largely align with what is reported here). In sum, based on the above considerations, 17% may be an optimistic estimate of the prevalence of collaborations.

Depending on one’s perspective, the results of this analysis may either be encouraging or discouraging. For instance, some might cite this as evidence that I-O psychology does a good enough job of incorporating nonacademics into the research process (notwithstanding the limitations noted above), whereas others might say this shows the field can do better with respect to collaborative research. We take the position that the field of I-O psychology can do better and, as noted throughout this paper, take the stance that increased efforts to engage in research collaborations (which would be reflected by an increased number of nonacademic authors across I-O psychology journals) will ideally yield more relevant and useful research. It is our hope that the results reported here can provide some useful initial insights about the status of collaborations within I-O psychology, inform both present and future discussions about the current state of research collaborations, and serve as a motivator for I-O psychologists to practice engaged scholarship and thus conduct more collaborative and inclusive research. To further support our stance of a need to increase research collaborations within the field of I-O psychology, we now discuss the concept of engaged scholarship in greater detail.

Defining engaged scholarship

Engaged scholarship has been defined as “a participative form of research for obtaining the different perspectives of key stakeholders (e.g., researchers, users, clients, sponsors, practitioners) in studying complex problems” (Van de Ven, Reference Van de Ven2007, p. 9). As noted in this definition, many different types of stakeholders exist, and the involvement of these various stakeholders is dependent on the context and topic of the research project. Similar overlapping research approaches include “action research,” “mode 2 research,” “process consultation,” “partnered research,” and “community-based participatory research” (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Bonaccio, Jetha, Winkler, Birch and Gignac2023; Guerci et al., Reference Guerci, Radaelli and Shani2019; Heracleous, Reference Heracleous2022; Martin, Reference Martin2010). Although there are subtle differences in the assumptions and methodologies underlying these approaches, at their core is a view that research conducted as partnerships between academics, practitioners, and other stakeholders can yield more rigorous and relevant outcomes than research conducted by any of these parties alone.

Much of the essence of engaged scholarship can be captured by the following quote from Van de Ven (Reference Van de Ven, Bartunek and McKenzie2018b) who stated:

Instead of viewing organizations and clients as data collection sites and funding sources, an engaged scholar views them as a learning workplace (idea factory) where practitioners and scholars co-produce knowledge on important questions and issues by testing alternative ideas and different views of a common problem. (p. 123)

Such partnerships can be initiated with differing motivations and/or goals by either a stakeholder (e.g., a leader trying to solve an organizational problem) or a researcher (e.g., an academic or practitioner interested in conducting research on the most pressing problems within organizations), which can be mutually beneficial for all stakeholders. For example, practitioners can conduct more applicable and relevant research within organizations full of employees facing real problems and can find realistic solutions that truly help them, whereas academics can have the opportunity to expand on theory in a real-world setting and publish the findings. More importantly, all parties can benefit from the resulting enhanced rigor and power that stems from collaborative research, thus improving the practical importance and utility of it. Although there are challenges to practicing engaged scholarship and engaging in successful collaborations (see below), there are success stories and guidelines available to academics, practitioners, and any other stakeholder interested in conducting collaborative research (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Bonaccio, Jetha, Winkler, Birch and Gignac2023; Heracleous, Reference Heracleous2022; Lapierre et al., Reference Lapierre, Matthews, Eby, Truxillo, Johnson and Major2018; Lawler & Benson, Reference Lawler and Benson2022; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Levenson and Crossley2015).

In the next section, we more explicitly highlight some of the advantages of engaged scholarship to the field of I-O psychology. Although we assert that this collaborative form of research will advance the impact of I-O psychology, to ensure a fair consideration of the approach, we also note some challenges and potential limitations of engaged scholarship.

Benefits and challenges of engaged scholarship

Benefits of engaged scholarship

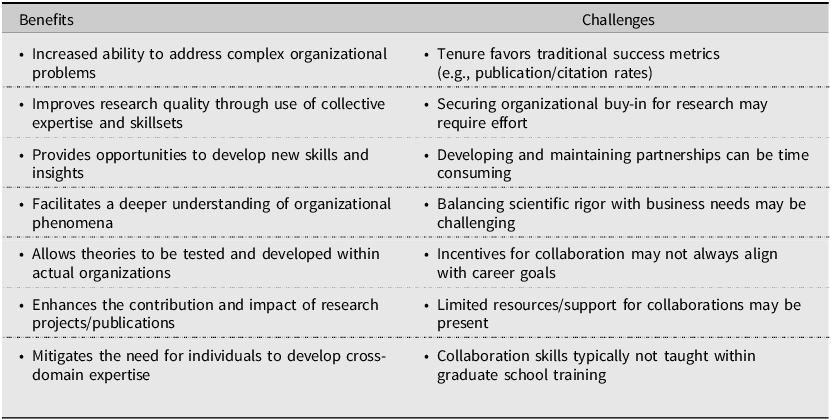

There are various benefits of collaborative research like engaged scholarship (see Table 3 for a summary of the benefits and challenges). For example, Rynes et al. (Reference Rynes, McNatt and Bretz1999) found that research conducted by academics within organizations was associated with higher citation rates compared to research conducted outside of organizations. In a similar vein, Baldridge et al. (Reference Baldridge, Floyd and Markóczy2004) found journal articles with higher citation rates tended to also be viewed as more practically relevant (as judged by consultants, executives, and HR professionals). Moreover, other research found that involving key stakeholders in data analysis led to higher quality projects and thus argued that stakeholder involvement can more effectively meet the needs of research projects and an organization’s stakeholders (Prell et al., Reference Prell, Hubacek, Quinn and Reed2008).

Table 3. Summary of the Benefits and Challenges of Engaged Scholarship

Beyond some of the initial empirical research on the topic of engaged scholarship, there are also compelling conceptual reasons as to why it can be beneficial. For example, many problems faced within the organizational sciences are very complex and unlikely to be solved without involving multiple perspectives. That is, without engaged scholarship, it is more difficult to identify and solve organizational problems because only one stakeholder group (e.g., academics) is involved throughout the research process (Van de Ven, Reference Van de Ven2007). A lack of these various perspectives may also lead to asking the wrong questions and proposing unworkable solutions. One of the key benefits of engaged scholarship is that it increases the diversity of the perspectives (e.g., akin to how good teams function) represented throughout the research process (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Bonaccio, Jetha, Winkler, Birch and Gignac2023). This depth of knowledge can thus increase the relevance of the research and the likelihood of addressing some of I-O psychology’s most challenging research topics (see Banks et al., Reference Banks, Pollack, Bochantin, Kirkman, Whelpley and O’Boyle2016; Mullins & Olson-Buchanan, Reference Mullins and Olson-Buchanan2023).

Moreover, engaged scholarship enables the collaborative utilization of the I-O knowledge base and the collective insights of the collaborative research team (which includes all stakeholders) to solve practical problems while also creating opportunities to develop new theoretical insights. As noted above, researchers work with a variety of diverse stakeholders (e.g., employees, managers, leaders, consultants, engineers, product managers, unions, committees) to understand and solve problems facing organizations (e.g., increased turnover during onboarding). This approach allows for a deeper understanding of problems the organization is facing, the boundary conditions, and the most realistic solutions. The collaborative research team can use insights from academics who have deep expertise in the topic area and practitioners who have leverage inside of the organization to ensure the project is moving forward and that the organization is aligned and bought in. For example, practitioners could include input from managers and HR representatives who understand the workforce being studied and/or union representatives to ensure employee protections and who have legal insight into any compliance, legality, and confidentiality concerns. The team can then design research according to their related knowledge areas (e.g., onboarding and attrition). In doing so, they may at times draw from theory (e.g., attraction-selection-attrition theory, person–job fit, unfolding model of turnover) and/or empirical findings to provide a starting point for helping solve an organizational problem. In other instances, researchers work on developing, testing, and validating interventions, assessments, and products (e.g., HR technology products) whereby the data collected could inform theory development (i.e., grounded theory; Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2015), and including more stakeholders in these research processes can result in more usable and valid outcomes, because more practicality is built into the research process from day one. Thus, this participative model can provide a fruitful path toward more practical applications of I-O research.

It is impractical for either academics or practitioners to learn the necessary skills and take the time needed to be successful alone in closing the academic–practice gap by producing more relevant and impactful research. The collaborative nature of engaged scholarship may be more realistic and effective, however, because it allows multiple parties to remain experts in their own area and work together without necessarily needing to develop expertise in other new domains. This team-based approach makes engaged scholarship a particularly effective way to address the academic–practice gap and can help address some of the limitations in other approaches for reducing the gap that have been suggested (e.g., developing cross-domain expertise). Although there are no doubt benefits to engaged scholarship, there are also challenges to adopting this approach.

Challenges to engaged scholarship

An unfortunate reality of engaged scholarship is its rarity and difficulty as a career path for many in our field. For I-O academics, systemic incentive issues such as tenure criteria with a focus on the quantity of academic journal publications, citations, and impact factors prevent many faculty from conducting more engaged research due to the perceived compounding opportunity costs to their career (Aguinis et al., Reference Aguinis, Cummings, Ramani and Cummings2020). Indeed, prior to conducting the research, it may take multiple years to develop a trusting relationship with an organization and the stakeholders needed for a specific engaged research project. Though this assumption about the time-consuming nature of these projects can discourage some from ever collaborating in the first place, it is important to recognize that when conducting collaborative research projects, these don’t have to be extremely large or time consuming. Unfortunately, especially prior to tenure, most faculty focus on what they believe are “safe bets” for yielding publication in top tier journals, and they continue with approaches that are in widespread use, despite preliminary evidence on the benefits to engaged scholarship noted above (e.g., accumulating more citations). Academics who work outside the boundaries of traditional academia are in the minority, a theme present throughout the history of I-O psychology (Lawler & Benson, Reference Lawler and Benson2022). Thus, most graduate students and researchers with a desire to do more applied or collaborative research may have fewer resources to draw upon to expand their research (Lawler & Benson, Reference Lawler and Benson2022). For example, creating opportunities for collaborative research projects through networking and marketing is necessary for lead generation (Lemoine, Reference Lemoine2023), and understanding what kind of research is relevant and interesting to organizations (Lawler & Benson, Reference Lawler and Benson2022) and how to identify issues of joint interest is crucial (Lemoine, Reference Lemoine2023). Although collaborative research projects don’t require more time than traditional research, some academics may worry that time spent on these activities could pose career-related challenges and distract from activities perceived as more crucial (or “collaboration costs,” see Banks et al., Reference Banks, Pollack, Bochantin, Kirkman, Whelpley and O’Boyle2016). However, this should not dissuade academics from trying to conduct collaborative research. I-O psychology is a form of applied psychology, and it is I-O psychologists’ responsibility to help examine and address the most pressing needs and concerns within organizations and among their members.

Challenges also exist for I-O practitioners wanting to engage in collaborative research. Whether a practitioner is in house or not, they must get the organization to understand the value of collaborative research and agree to it. Convincing an organization to allocate the time and effort needed for a collaborative research project is a notable challenge. Organizations may be hesitant to engage in collaborative research due to concerns of legality issues, confidentiality requirements, a lack of time and resources, or to save face; however, with true collaboration (and not just data collecting), the organization will care as much about the project as the researcher. Some organizations might view the research as proprietary and may not want it to be available for public dissemination (Van De Ven, Reference Van de Ven2018a). Practitioners must know how to navigate the legal landscape that coincides with conducting collaborative research or be able to add a stakeholder to the team who has a valuable perspective on these issues. There is an entire skillset not usually taught in graduate school that can make practitioners more successful at getting buy-in for collaborative research projects, such as networking to identify stakeholders within the organization who have the most leverage to get approval for projects and being able to tie the collaborative research project to the strategic plan of the organization to drive value for their existing goals. Thus, practitioners and others on the research team (e.g. academics and other stakeholders) must work in tandem to explore the needs of the organization and to identify problems of shared importance (Lemoine, Reference Lemoine2023). The ability to overcome these barriers by leveraging the collective skill set of the collaborative research team is, however, one of the key benefits of engaged scholarship.

Furthermore, after a practitioner successfully gets an organization to agree to engage in collaborative research, and an academic manages to counteract the collaboration costs associated with this research approach, there may still be challenges to overcome. Creating successful collaborative research teams can be challenging (Amabile et al., Reference Amabile, Patterson, Mueller, Wojcik, Odomirok, Marsh and Kramer2001). This difficulty, however, does not imply an inability to harness insights from our own field’s research to overcome this obstacle. A 4-year study on cross-profession collaborative teams revealed the same recommendations that help any heterogeneous team work effectively together (Hackman, Reference Hackman1991) also apply to collaborative research teams (Amabile et al., Reference Amabile, Patterson, Mueller, Wojcik, Odomirok, Marsh and Kramer2001, See Van de Ven, Reference Van de Ven2018a for a summary of recommendations). We feel that if we are expecting people outside the field of I-O to utilize our research findings to improve organizations and teams, we should do so ourselves.

During the research process, collaborative research may be further challenged by the need to balance our scientific integrity while making necessary compromises to meet organizational and strategic goals in a timely manner. In fact, such conflict of interests might pose a challenge to the seamless collaboration between industry and academia in the realm of I-O psychology research. Academics are likely to prioritize the pursuit of scientific knowledge and publication in prestigious journals due to career incentives, whereas industry partners are primarily driven by practical applications and organizational outcomes. The potential for financial or personal interests to influence research outcomes can undermine the credibility and objectivity of collaborative efforts. When anyone involved is swayed by financial considerations or personal motivations, the integrity of the research process is jeopardized. Such influences could lead to biased interpretations or selective reporting of results, all of which compromise the reliability and impartiality of the findings. Striking a delicate balance between academic rigor and the practical needs of the industry is essential. Transparent communication, clear guidelines on ethical considerations (which are abundant in our field, see Banks et al., Reference Banks, Knapp, Lin, Sanders and Grand2022), and a shared commitment to maintaining the integrity of the research process are imperative to mitigate conflicts of interest and foster productive and trustworthy collaborations in I-O psychology research. Fortunately, there are many guidelines available for how to participate in engaged scholarship (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Bonaccio, Jetha, Winkler, Birch and Gignac2023; Heracleous, Reference Heracleous2022; Lapierre et al., Reference Lapierre, Matthews, Eby, Truxillo, Johnson and Major2018; Lawler & Benson, Reference Lawler and Benson2022; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Levenson and Crossley2015). Moreover, the various stories of successful collaborations by I-O psychologists (including many of the authors of this paper) demonstrate that these challenges are not insurmountable.

In summary, we believe the benefits of collaboration make it well worth the effort. Collaborative research in I-O psychology has the potential to yield richer insights, innovative solutions, and a more comprehensive understanding of complex organizational and personnel issues. The synergy achieved through interdisciplinary perspectives and collective expertise often produces outcomes that surpass what individual efforts could achieve. In essence, the benefits of collaboration—enriched knowledge, practical applications, and broader societal impact—outweigh the potential costs and inherent challenges in engaged scholarship initiatives.

Instilling engaged scholarship into the research process

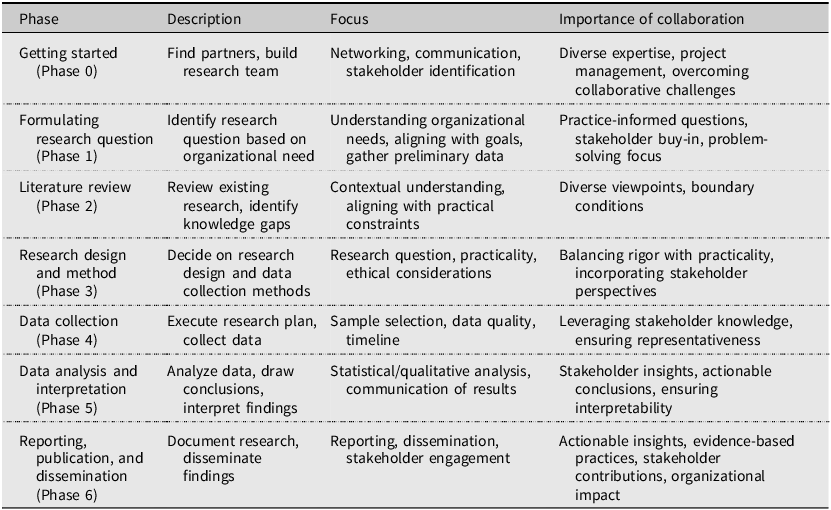

We next present recommendations for enhancing engaged scholarship across the various phases of the research process, offering examples from both industrial (I-side) and organizational (O-side) psychology research (see Table 4 for a summary of recommendations). The following examples come from both previous literature and the expertise of many of the authors of this paper, who have spent their careers conducting engaged scholarship to varying degrees. There are no shortcuts to doing engaged scholarship; we must each find our own authentic style and ways of getting engaged, developing understanding, collaboratively forming our questions, persuading partners to join projects, and ultimately getting things done. Although we know that the barriers to engaged scholarship mentioned above are still pertinent, these examples aim to illustrate how principles of engaged scholarship and collaboration can be seamlessly integrated into the entire research process, ensuring academic rigor and practical applicability, and thus enhancing the overall value and impact of I-O psychology.

Table 4. Summary of Recommendations for Integrating Engaged Scholarship Throughout the Research Process

Phase 0: getting started

This stage of the research process involves finding organizational partners and assembling a collaborative research team. Networking strategies vary from passive approaches, such as writing for nonacademic audiences on relevant topics to attract potential partners (Pagel & Westerfelhaus, Reference Pagel and Westerfelhaus2005), to more direct methods like reaching out to identified individuals within companies (Lemoine, Reference Lemoine2023). Utilizing university resources, such as alumni associations or business school executive programs, can facilitate introductions.

Once potential partners are identified, outreach begins. Lemoine (Reference Lemoine2023) exemplifies a successful approach where he introduces himself as a professor studying employee behavior, seeking collaborations to address organizational issues. This initial contact focuses on understanding the organization’s challenges and finding opportunities for collaboration rather than presenting a specific research question upfront.

Building relationships with stakeholders who bring diverse expertise is crucial for enhancing the research project. These stakeholders, including high-level executives (Bleijenbergh et al., Reference Bleijenbergh, van Mierlo and Bondarouk2021; Van de Ven, Reference Van de Ven2007), provide valuable contextual insights, diverse skill sets, and access to resources. For instance, involving a Human Resource Information Systems expert ensures alignment with organizational data practices and identifies potential data gaps or errors.

Successful engagement in this phase requires various skills, including adapting communication styles between academia and business, mastering project management and consulting skills like scoping projects and managing stakeholder buy-in, and fostering collaborative relationships. Learning from diverse perspectives within the team mitigates collaboration challenges (Banks et al., Reference Banks, Pollack, Bochantin, Kirkman, Whelpley and O’Boyle2016), overcomes barriers, and enhances the prospects of successful research collaborations.

Phase 1: formulating the research question (and/or hypothesis)

This stage involves identifying a specific area of interest that arises from a need within the organization or applied setting. The research question will guide each phase of the process, influencing the choice of method, data collection, analysis, and resulting implications for practice. To succeed at engaged scholarship, researchers must invest time and energy in understanding the work and lives of those impacted by the research by interviewing, listening, and observing to identify organizational needs (Bleijenbergh et al., Reference Bleijenbergh, van Mierlo and Bondarouk2021; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Bonaccio, Jetha, Winkler, Birch and Gignac2023). This requires formative research within the organization, spending time on site learning about the culture, employees, and real-world problems. Involving employees and leaders in problem identification enhances buy-in and relevance, which is crucial for long-term commitment and investment (Bleijenbergh et al., Reference Bleijenbergh, van Mierlo and Bondarouk2021; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Bonaccio, Jetha, Winkler, Birch and Gignac2023). Researchers and stakeholders collaboratively identify a mutually important problem and generate research questions, focusing on practical issues integrated into a clear, focused research question or hypothesis.

In this process, researchers should seek to understand the realities of the work performed in the organization to add the most value. Aligning with the organization can involve assisting with strategic initiatives, enhancing the organizational brand, reducing turnover, improving safety and well-being, or bringing higher efficacy and rigor to existing processes. This requires authentic connections with people, asking questions during informal times like worksite tours, and attending events like trade association conferences. Techniques like work shadowing, focus groups, analyzing organizational data, and needs assessments help identify the organization’s pain points.

Although theoretical and technical inquiries lay the foundation for problem-solving, it is crucial to identify questions reflecting practical realities and challenges within the organization. For example, an academic with expertise in leadership can work with the organization to understand their leadership issues, potentially incorporating leadership theory into an experimental intervention. In personnel selection, academics might explore conditions enhancing a machine learning algorithm’s predictive precision, whereas practitioners may compare predictive precision between conventional methods and advanced algorithms, considering factors like training data scarcity and candidate pool variations. Additionally, in validating the job demands-resources theory (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007), academics might focus on distinctly identifying demands and resources, while practitioners may explore how these factors are perceived differently by workers and how managers can leverage this knowledge to improve employee well-being and productivity. Thus, developing a research project of mutual interest and benefit is essential.

Phase 2: literature review

This phase of the research process involves understanding the organizational context, goals, and constraints; reviewing prior studies; pinpointing knowledge gaps; and leveraging existing findings. It guides the study trajectory and helps formulate hypotheses or predictions. Before commencing research, it is crucial to review existing literature in the field, such as research articles, and within the organization, such as strategic plans and other union and company materials. In some cases, it is necessary to start the literature review earlier in the research process to be informed about the industry in question prior to networking for collaboration leads. Engaged scholarship can enhance this literature review phase by focusing on literature that meets both academic and practical standards, and by incorporating diverse collaborator viewpoints to better understand boundary conditions and organizational context. If a study relies on past research that didn’t consider practical constraints in real work settings, its findings may hold significance only under unrealistic assumptions, limiting their practicality. For instance, job candidates may display different attitudes toward job opportunities depending on the socio-economic environment (e.g., economic recession, unemployment benefits). By incorporating insights from relevant stakeholders on the context of personnel selection decision making, literature that accounts for these crucial contexts can be selectively reviewed for a study.

In another scenario, a school district may aim to reduce teacher burnout, which is theoretically defined by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and diminished personal accomplishment (Maslach & Jackson, Reference Maslach and Jackson1981). Workers experiencing burnout might still perform highly due to dedication, commitment, loyalty, or fear of job loss. Therefore, it might be more reasonable to focus on emotional exhaustion and depersonalization as primary indicators of burnout rather than compromised performance to assess workers’ burnout experience in certain contexts. Diverse viewpoints are crucial in identifying these unique contexts and should be reflected in the literature review for a study.

Phase 3: research design and method

This stage involves deciding on the research design (e.g., experimental, quasi-experimental, or observational) and the specific methods and tools for data collection. Decisions on design and methods will be guided by the research question and practicality, and include determining sample size, participant selection criteria, and ethical considerations. Researchers, rather than stakeholders, often dominate these decisions due to their expertise in rigorous design and methods, potentially overlooking real-world constraints that should influence the design. Organizational collaborators provide crucial perspectives to evaluate designs for practicality, augmenting the study’s rigor and acceptance (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Bonaccio, Jetha, Winkler, Birch and Gignac2023; Van de Ven, Reference Van de Ven2018a).

For instance, research might emphasize the technical validity of selection tests without considering their practicality or relevance in real workplace settings. A highly valid test might be too time consuming or complex for fast-paced hiring processes. Stakeholder perspectives can highlight the importance of practicality, incorporating variables like psychological acceptability and various costs (e.g., test development and training) into personnel selection research. In another scenario, an intervention study on a critical organizational issue (e.g., mistreatment) might emphasize a randomized control trial approach, but a stepped-wedge or multiple baseline design could be considered. These designs allow everyone in the organization to benefit from the intervention while maintaining experimental rigor. Decisions regarding who receives the intervention and the program’s design in terms of modality, frequency, and duration can be made through discussions between researchers and organizational collaborators (Bleijenbergh et al., Reference Bleijenbergh, van Mierlo and Bondarouk2021).

Unexpected organizational constraints, such as key stakeholder turnover, company mergers, global pandemics, and union management issues, must also be managed. This messiness is the reality of working in applied settings. Preliminary conversations about potential future disruptions, establishing protocols for handling them, maintaining effective communication, documenting changes, and accounting for them in the analysis and interpretation can help ensure the success of the collaborative research project.

Phase 4: data collection

This step involves executing the research plan, collecting data, and ensuring the quality, integrity, security, and privacy of the gathered data (Bleijenbergh et al., Reference Bleijenbergh, van Mierlo and Bondarouk2021). Leveraging the diverse knowledge and connections of various stakeholders is crucial for choosing a representative sample, setting an effective data collection timeline, and accessing archival and other preexisting organizational data (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Bonaccio, Jetha, Winkler, Birch and Gignac2023). Researchers contribute methodological expertise and theoretical knowledge, whereas collaborating stakeholders provide invaluable insights into practical field nuances and contexts, collectively enhancing research rigor (Van de Ven, Reference Van de Ven2007).

Collaborating with knowledgeable stakeholders helps researchers design an optimal data collection timeline and select a representative sample. For instance, personnel selection researchers might prioritize the availability of research resources, potentially overlooking seasonal and cyclical factors that influence job candidate representativeness. Industries can experience shifts in applicant volumes and profiles due to recruitment cycles aligned with organizational needs. For example, retail sees a surge in holiday season applications, and academic cycles, especially during graduation periods, shape candidate demographics and skill sets, impacting the job market. These variations offer opportunities to explore candidate representativeness across different contexts.

In another scenario, researchers might lack a solid theoretical rationale for the interval between measurements in a repeated measure design study assessing organizational well-being intervention effectiveness. In contrast, stakeholders such as in-house I-O practitioners or HR representatives could provide compelling reasons for specific time intervals, considering factors like forthcoming organizational changes, worker busyness and availability throughout the year, turnover rates, and the overall volatility of the organizational phenomena of interest.

Phase 5: data analysis and interpretation

After collecting data, the next step involves analysis using suitable statistical or qualitative methods to draw conclusions, test hypotheses, and interpret findings. When researchers collaborate with stakeholders, data analysis and composing the results section often become the researcher’s main tasks (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Bonaccio, Jetha, Winkler, Birch and Gignac2023). This is unsurprising, given the need for meticulous attention to detail and expertise in complex statistical and mathematical modeling. However, involving stakeholders in these processes can be extremely beneficial (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Bonaccio, Jetha, Winkler, Birch and Gignac2023). Collaborating with stakeholders such as organizational leaders and frontline managers fosters a deeper understanding of result implications. Their contextual insights often reveal nuances not apparent from the data alone, ensuring accurate interpretation and communication of the results. Stakeholders’ insights into the practical implications of research outcomes initiate discussions on real-world applications, leading to actionable conclusions. Engaging stakeholders in the analysis also helps interpret findings, as their feedback and critique bolster research robustness, aligning results with practical experiences and expectations (Bleijenbergh et al., Reference Bleijenbergh, van Mierlo and Bondarouk2021; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Bonaccio, Jetha, Winkler, Birch and Gignac2023; Van de Ven, Reference Van de Ven, Bartunek and McKenzie2018b). Organizations with in-house analysts benefit directly from stakeholder perspectives, whereas those without can facilitate involvement by using accessible, user-friendly software and presenting results clearly to nontechnical audiences. Ensuring interpretability of analysis results is crucial, achieved by using plain language, user-friendly figures, tables, and detailed notes (Murphy, Reference Murphy2021; Voss & Lake, Reference Voss and Lake2020; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Highhouse, Brooks and Zhang2018). This is based on an iterative process of participatory interaction between researchers and stakeholders.

An exemplary instance is the ongoing collaboration in the Fire Service Organizational Culture of Safety project by the Center for Firefighter Injury Research and Safety Trends. Using “teach-back” sessions (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Allen, Shepler, Resick, Lee, Marinucci and Taylor2020), the project engaged firefighters and emergency medical services in validating results and generating new research questions, leading to iterative research with a scientific focus (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Resick, Allen, Davis and Taylor2024) and a practice-oriented perspective (Raposa et al., Reference Raposa, Mullin, Murray, Castro, Fisher, Gallogly, Davis, Resick, Lee, Allen and Taylor2023).

Phase 6: reporting, publication, and dissemination

This stage involves documenting the entire research process, findings, and interpretations, and sharing them with a broader readership. After conducting research, researchers typically write a research paper or report summarizing their work, which may be submitted for publication in academic journals or presented at conferences to share findings within the scientific community. This process is often regarded as a performance indicator for academics, leading them to focus on publishing as many studies as possible in high-impact journals (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Bonaccio, Jetha, Winkler, Birch and Gignac2023). However, this focus on publication as a performance indicator often overlooks stakeholders’ potential contributions (Simsek et al., Reference Simsek, Li and Huang2022). Stakeholder involvement is crucial for advancing evidence-based organizational practices in I-O psychology, improving organizational effectiveness, and enhancing worker quality of life.

For instance, the stakeholders that are closest to the issue can contribute greatly in outlining the practical implications of validity indexes in new personnel selection assessments, ensuring understanding of study findings, their applicability, and limitations in relevant contexts. Post publication, collaborative sessions involving stakeholders, workers, and researchers are vital for deriving actionable insights and establishing effective action plans, thereby ensuring research impacts workplace practices effectively. Additionally, researchers can disseminate implications via podcasts, blogs, vlogs, trade publications, and other nontraditional outlets. Emphasizing scientific rigor throughout is essential.

Moreover, researchers should recognize the diversity of research approaches beyond traditional I-O psychology methods. For example, in product development such as domains of HR technology (i.e., relevant to talent assessment or development, leadership development, etc.), researchers act as subject matter experts (SMEs), synthesizing evidence into actionable insights and product specifications. They collaborate closely with product teams to address key problems, gather requirements, and develop valuable solutions. Researchers also collaborate with product managers and engineers to define and measure objectives and key results, validating the effectiveness of new features or solutions through well-designed studies informed by academic insights on sampling methods, sample sizes, and assessment strategies. Flexibility and creativity in engaged scholarship can yield innovative research insights by exploring diverse collaborative approaches.

Call to action

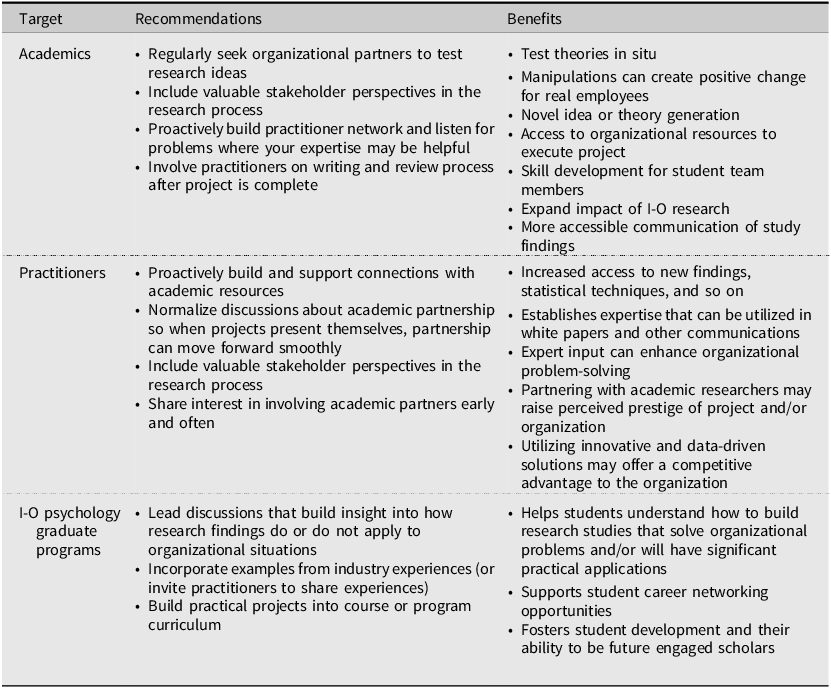

Research in I-O psychology and related disciplines has become increasingly theoretical and decreasingly relevant to practice (O’Boyle et al., Reference O’Boyle, Götz and Zivic2024; Rogelberg et al., Reference Rogelberg, King and Alonso2022). If we are truly an applied field, more of our work should have direct relevance to practice. Our call to action is for I-O academics, practitioners, and leaders of graduate programs, with the goal of reducing the academic–practice gap and enhancing the relevance of I-O psychology to society (see Table 5 for a summary of the call to action).

Table 5. Summary of Call to Action and Recommendations for Increasing Engaged Scholarship

Academic recommendations

We recommend that I-O academics seek opportunities to collaborate with I-O practitioners and other stakeholders on projects that solve existing organizational problems while contributing to the scientific knowledge base of the field. This will require academics to acquire new skills and strategies, as well as a different mindset. Although current approaches (e.g., using department subject pools or online panels) are producing publication success, true partnerships can allow access to organizational data, organizational resources needed for the project (with or without having to write research grants), and experimentation where meaningful variables can be manipulated. This type of collaborative research can allow for a more complete understanding of organizational phenomena from which new theory can emerge and for more rigorous tests of existing theory, all while having a direct positive impact on organizations and people. Partnering requires flexibility and a willingness to get off campus and into the field, especially when finding valuable stakeholders to incorporate into the research process. It means sitting down with I-O practitioners and other stakeholders to listen to their challenges and problems, and then developing research strategies that solve the organization’s problem while generating publishable data. The methods might range from conducting surveys to helping develop, implement, and evaluate interventions and randomized field experiments.

Additionally, academics can proactively involve students in collaborative projects to provide a unique experiential learning opportunity. This enriches academic research and prepares the next generation of I-O psychologists with practical insights and skills. Furthermore, fostering interdisciplinary collaborations with experts from non-I-O fields can bring fresh perspectives and innovative approaches to problem-solving, expanding the impact of I-O psychology beyond its traditional boundaries. Last, academics are uniquely positioned to advocate for major I-O journals to encourage more practical research papers and academic technical reports. Specifically, academics can work to invite I-O practitioners as reviewers to evaluate the practical implications of scientific manuscripts, thus enhancing the practical relevance of academic work. These additional recommendations underscore the importance of dynamic, hands-on engagement for academics, ensuring their work not only advances theoretical understanding but also directly contributes to real-world organizational challenges.

Practitioner recommendations

I-O practitioners must stay up to date with emerging research and resources through their own efforts or by partnering with an academic who can share their knowledge. It is easy to fall behind with the research literature once it is no longer required for graduate studies and university library access is lost. The SIOP Research Gateway is a great resource, but this only works well for those who have the time to conduct literature reviews and identify resources. For the many who do not have the time for reading research, partnering with an academic can also be a great way to keep up the flow of research information. Collaborating with researchers via engaged scholarship can be another way to tap into recent research that can benefit the organization or specific project.

Additionally, practitioners must maintain their statistical skills. A number of important key performance indicators (KPIs) can be tracked with simple descriptive statistics, and although those in industry may hone precise skills in churning out sophisticated Excel files or building PowerBI dashboards, inferential skills may fall out of practice. Thus, collaboration where researchers can provide statistical techniques necessary for key projects, and industry collaborators can contribute expertise in knowing what organizations may expect regarding descriptive characteristics and visualizations is needed.

The above points rest on the assumption that an I-O psychologist working in industry who wishes to collaborate has ample academic connections with expertise in various areas to call upon whenever a collaboration opportunity exists. The truth is, much like the advice to I-O academics, these partnerships can take time to nurture. It takes time to determine if the project is a good fit to invite outside collaborators to and if the project, in turn, is a good fit for the researcher’s needs. Investing in these working relationships before there is need can help facilitate collaboration when an appropriate project is identified. For example, practitioners can share the types of projects one’s company is working on with local graduate programs to see if there is a mutual interest, and they can also share a high-level list of current projects on a platform like linkedin to help interested researchers see what types of topics are available.

Graduate program recommendations

We recommend that I-O graduate programs place more emphasis on how research findings can be applied to organizations. Many programs do a wonderful job of supporting their students to have careers as academics, practitioners, or somewhere in between. For some academics though, it can be inherently easier to teach students a more academically focused set of skills. Reading and discussing academic journal articles during graduate seminars is a critical part of I-O education. More effort, however, can be made to discuss how research findings apply to organizations (or in some cases why they do not), as well as other favorite topics such as study design and statistical analysis nuances. Academics with industry experience can bring valuable examples to their classrooms so students both understand research best practices and the messiness of applying them to real organizations. Alumni and other practitioners can be invited regularly as guest speakers both to the broader department colloquia or as experts on topics particular to individual classes. Even students keen to enter academia may benefit from applied experience as a means to increase their social network and better understand how to build research that helps answer meaningful organizational challenges.

We also recommend that I-O graduate students get hands-on collaborative research opportunities and applied projects. Graduate programs can help students focus on practical applications by assigning both research and applied projects across their courses. Research proposals written for classes can be leveraged into executable studies and publications, but carving out time for practical skills is essential too. For example, faculty with ongoing collaborative industry projects can invite students to gain experience, and some programs may even offer practicum credits for applied work to support both skill development and degree progress for students. Supervising field or applied work through a formal course offering can be one way to help ensure faculty have dedicated time to work collaboratively and include students in these important developmental activities. If an opportunity to involve students in a collaborative applied project doesn’t exist, university or department problems could be used. Specifically, students could be asked to propose a selection process for vetting interested undergraduates to join their research lab or to evaluate an existing graduate student mentorship program. Students can consider how their recommendations may differ based on creating a deliverable for their client (the department) versus using this field opportunity as a way to collect data for a publishable project.

In sum, we hope this call to action serves as a catalyst for I-O academics, practitioners, and graduate programs to find more ways to better realize the potential of research collaborations in general and engaged scholarship in particular. I-O psychologists can have a tremendous impact on the world of work and when academic researchers collaborate with practitioners, there can be more powerful results ready for immediate application in organizations.

Conclusion

Although I-O psychology research has the potential to shape the future of work in many ways, the impact that it will have is contingent on its ability to address issues relevant to organizations and society. This vision of the future of I-O psychology is not necessarily new but corresponds to a growing and increasingly louder call for I-O psychology to address the academic–practice gap and “move to the next level of meaningful social impact.” (Mullins & Olson-Buchanan, Reference Mullins and Olson-Buchanan2023, p. 485). As noted throughout this paper, we believe inclusive collaborations in general, and engaged scholarship in particular, are ways to help move I-O psychology closer to this ideal. Will engaged scholarship be easy? It depends! Doing something new is rarely easy at first, but not doing something because it is too hard is not a compelling reason for inaction. Will engaged scholarship guarantee I-O psychology’s relevance? No, but stepping outside our perspective and idiosyncratic interpretation of the world and working with others who possess unique viewpoints can incrementally move us in a positive direction. One could potentially criticize our discussion as yet another attempt to address the academic–practice gap that will ultimately not yield any success. Although the persistence of this gap might induce skepticism about further calls to action, it is our perspective that ideas and discussions are not empty but are necessary prerequisites for change. Thus, the persistence of the academic–practice gap is the very reason we need to keep having conversations about what can be done about it. For I-O psychology to stay vibrant and realize its full potential, we collectively need to leverage the power of broader collaborations.