Pay inequality between men and women remains a salient societal issue. Research has shown that much of the pay gap can be attributed to sex segregation, which continues to permeate the workforce (i.e., women tend to populate different types of jobs compared with men; Bayard et al., Reference Bayard, Hellerstein, Neumark and Troske1999; Blau & Kahn, Reference Blau and Kahn2007; Ceci et al., Reference Ceci, Ginther, Kahn and Williams2014; Petersen & Morgan, Reference Petersen and Morgan1995). At the same time, it continues to be common for women to file claims of sex-based pay discrimination on the basis of pay gaps that exist between individual men and women who work in equivalent jobs.Footnote 1 In fact, the most common legal recourse for individual employees to demonstrate they are a victim of sex-based pay discrimination is for an individual to identify another employee who is, at a minimum, (a) of the opposite sex, (b) paid more, and (c) in an equivalent job (i.e., a comparator employee; Equal Employment Opportunity Commission [EEOC], 2000). That is, although an employer might ultimately defend a pay difference between an employee and an opposite-sex comparator employee as resulting from a variety of legitimate factors (e.g., seniority systems, merit systems), a pay discrimination case often begins with the plaintiff providing evidence of the existence of a better paid comparator employee. Providing sufficient evidence of a comparator is enough to create a presumption of discrimination (i.e., a prima facie case), requiring the employer to counter with evidence that the pay discrepancy is due to a legitimate distinction between the employees. Consequently, determining whether the jobs in question are truly equivalent is often a central issue in pay equality inquiries.

The topic of job equivalency is a deceptively complex one. Although some jobs are obviously not equivalent (e.g., a computer programmer versus a manager of a clothing department), the equivalency of many jobs is more ambiguous (e.g., a manager of a women’s clothing department vs. a manager of a men’s clothing department in the same store). Regardless of whether the focus is on comparing the work of employees who have the same or different job titles, it is necessary to establish whether any identified differences are meaningful enough to differentiate the work that is performed in terms of nonequivalence. Various legislative bodies, courts, and government agencies (e.g., the EEOC) have attempted to deal with the complexity of this issue by setting top-down standards for what makes two jobs equivalent (e.g., equal responsibility, skills, effort). However, for several reasons, these standards are not easy for organizations to apply. First, it can be challenging to understand what these standards mean in practice (e.g., what constitutes equal vs. unequal levels of responsibility). Second, the case law/legal precedent set by the courts (which does give concrete examples of how to apply these standards in practice) varies, can be contradictory across different jurisdictions (i.e., circuit courts), and can be difficult for organizations to access and interpret. Third, many states have recently adjusted their state-level equal pay laws, in some cases making current standards even more unclear (Miller, Reference Miller2018; Nagele-Piazza, Reference Nagele-Piazza2018). Finally, once these standards are understood, challenges arise in applying them on a broad scale (i.e., determining the equivalence of numerous jobs within an organization).

Previous work has been invaluable in summarizing equal pay employment legislation and (a limited amount of) case law (e.g., Coil & Rice, Reference Coil and Rice1993; Eisenberg, Reference Eisenberg2010; Sady et al., Reference Sady, Aamodt, Cohen, Hanvey and Sady2015). What is lacking, however, is guidance on how organizations can practically, proactively, and validly (from a statistical and psychometric standpoint) categorize jobs into equal pay bands in line with these legal standards. This paper contributes uniquely to the field not only by providing an expansive and updated summary of equal pay laws and regulations but also by integrating what we know about pay discrimination law with contemporary organizational research methods. That is, alongside our legal review, we describe methods that are commonly applied by industrial-organizational psychologists and human resource management specialists related to job analysis and job classification. In doing so, we focus on how modern job classification methods (based on job analysis methods) can be applied to the challenge of assessing and setting equal pay for equivalent work within today’s legal context. Although the general methods of job analysis and job classification have been used for decades as tried and true, bottom-up methods for systematically collecting information on jobs and subsequently categorizing jobs based on this information, they have not been interpreted, vetted, or modified in light of the (shifting) legal landscape related to pay equality. We provide the groundwork for this updated view of job analysis/job classification within an equal pay framework. Integrating the (legal) pay equality literature with the (methodological) job analysis/job classification literature allows both researchers and practitioners to engage in debate, discussion, and research surrounding the large-scale identification of equivalent jobs to facilitate fair and legal pay across the sexes. By positioning job analysis/job classification as a method that can meet this need, we also hope to initiate debate and dialogue on how the job analysis and job classification literature can remain current and continue to address real and unsolved problems within both organizations and society more broadly.

To begin this solution-focused conversation, we first review federal legislation related to equal pay across sex. We also describe legislative changes that are happening at the state level, paying special attention to the differences in seemingly similar vocabulary across legislation concerning whether jobs must be substantially equal, similar, or comparable (of a comparable character).Footnote 2 Importantly, we provide examples of how these laws are interpreted and applied to resolve specific issues in actual organizations. That is, we provide a sample of factors that have been used by the courts (over time and across different circuit courts and states) to differentiate jobs. We then discuss job analysis/job classification as a systematic method for determining the appropriate categorization of jobs and employees. Importantly, we discuss specific considerations that are necessary to adapt job analysis and job classification for the context of identifying pay discrimination. Finally, we discuss additional factors that are important to pay equality, such as how establishing a pay philosophy (i.e., a pay model) can increase the accuracy, fairness, and legal defensibility of pay decisions.

Compliance with pay discrimination laws

Several laws serve to hold employers accountable for fair pay across sex: the Equal Pay Act of 1963, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Executive Order 11246 (1965), and state-level equal pay laws.Footnote 3 Although we briefly cover the investigation and litigation stages mandated by these laws, our main focus is on the standards they set forth pertaining to the determination of equivalent jobs for the purpose of initially establishing the requirement of equal pay (i.e., the first phase in a pay discrimination trial; see Table 1 for summaries of how equivalent work is determined across these laws).

Table 1. Legal standards for plaintiffs to establish a prima facie case of pay discrimination

Equal Pay Act (EPA)

If a claim under the EPA goes to trial, it moves through three phases (Gutman et al., Reference Gutman, Koppes and Vodanovich2011; Vodanovich & Rupp, Reference Vodanovich and Ruppin press). In the first phase, an employee (the plaintiff) proves (i.e., makes a prima facie case) that they are underpaid compared with an employee of the opposite sex (the comparator) who performs work that is substantially equal. If a plaintiff meets this burden, the second phase requires the organization (the defendant) to make one of four affirmative defenses. That is, the organization must prove that although the jobs performed by the employees are substantially equal, the decision to pay the employees differently was based on seniority, merit, quality or quantity of work, or a factor other than sex (FOS).Footnote 4 Here, the defendant must provide sufficient proof that compensation decisions were based on the provided affirmative defense. Third, if the defendant succeeds in establishing an affirmative defense, the plaintiff must prove that the defense is pretext for sex-based pay decisions.

As stated above, the EPA uses the standard of substantially equal to compare jobs. Regardless of job title (29 C.F.R. § 1620.13, 2009), substantially equal jobs must have a common set of core work behaviorsFootnote 5 (“a significant portion of the tasks performed are the same”; EEOC Compliance Manual, 2000). If the jobs do have this common core of work behaviors, then the jobs should be assessed for whether they (in total) require substantially equal skill (e.g., experience, ability, training, education), effort (mental or physical exertion), and responsibility (accountability/supervisory responsibilities) and similar working conditions (narrowly referring to physical surroundings and hazards). The EEOC Compliance Manual notes that the working conditions requirement is less strict than the others are because it requires similar (as opposed to substantially equal) conditions. If any of these factors (core work behaviors, skills, effort, responsibility, or working conditions) differ meaningfully across the jobs, then the jobs are not substantially equal. Evidence that an employee from one job could easily replace the employee from another (i.e., the jobs are interchangeable) supports the notion that the jobs are substantially equal (Beck-Wilson v. Principi, 2006).

Compared with other standards (e.g., comparable, similar), substantially equal is generally viewed as strict, meaning fewer jobs would typically be grouped together under this standard compared with the comparable/similar standards. However, the actual strictness of this standard varies by jurisdiction (i.e., circuit court).Footnote 6 Eisenberg (Reference Eisenberg2010) reviewed 197 EPA circuit court cases through 2010, concluding that EPA precedent can be separated into two categories, “strict” and “pragmatic.” Courts that have applied the strict standard have required that jobs overlap very closely to be viewed as substantially equal. Indeed, whereas many courts have specified that the jobs need not be identical (e.g., Schultz v. American Can Co., 1970; Shultz v. Wheaton Glass Co., 1970), some courts have used stricter wording by stipulating that two jobs must have an overlap of identical core tasks (e.g., Cullen v. Ind. Univ. of Trs., 2003). This may only be possible for very standardized jobs such as assembly-line workers, and as such, the strict approach makes it challenging to compare manager and supervisory-level jobs. In contrast, courts that apply the pragmatic standard have allowed more flexibility in establishing that employees perform substantially equal work to a comparator. This has allowed, for example, supervisory jobs and jobs residing in different departments to be compared.

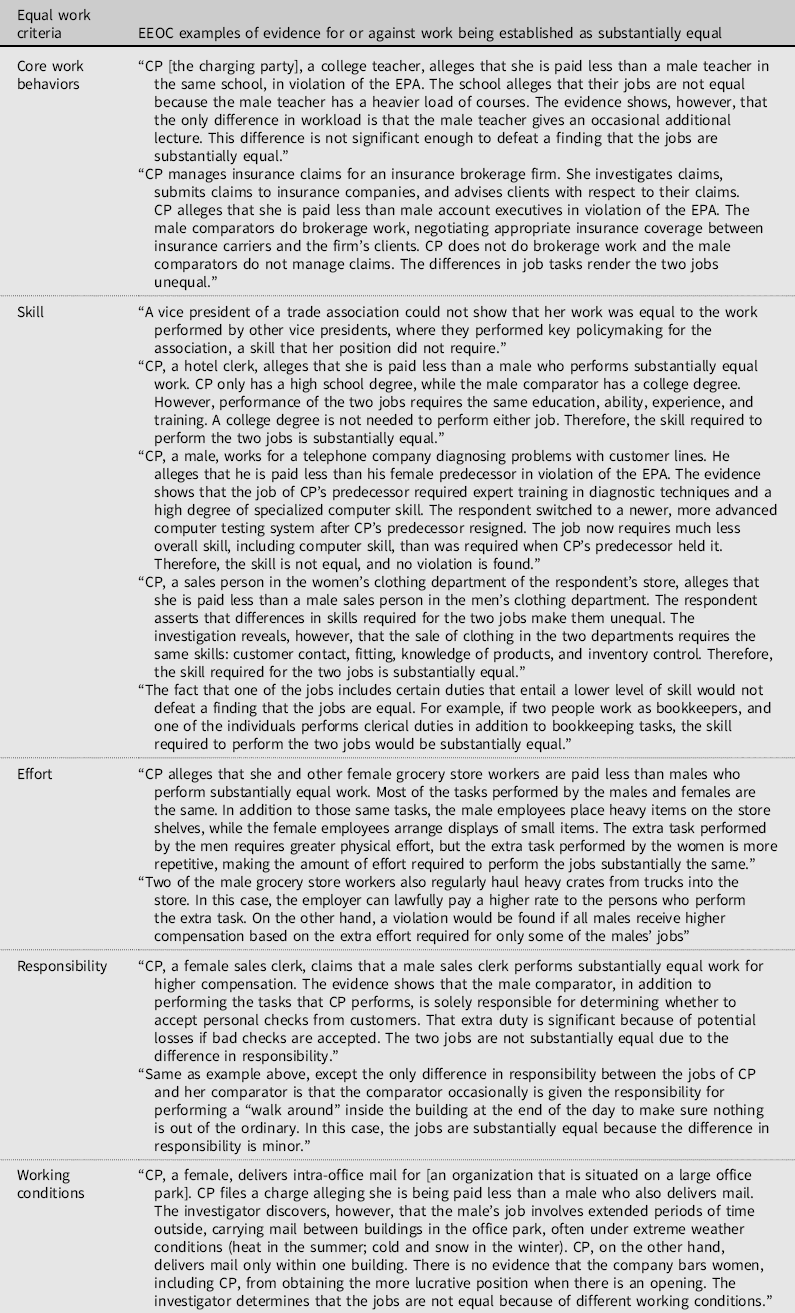

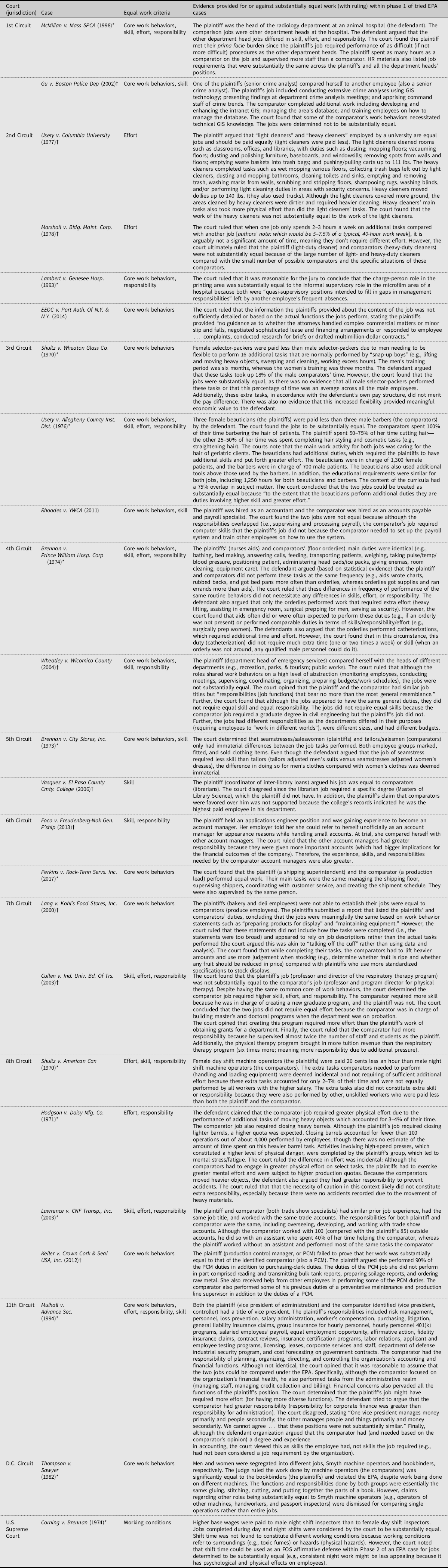

Tables 2 and 3 provide examples of substantially equal work. The examples in Table 2 come from the compensation discrimination section of the EEOC Compliance Manual, which details how much overlap work behaviors must have to demonstrate a common core of work behaviors and the types of additional skills, responsibility, effort, and working conditions that can differentiate jobs. Table 3 provides example precedent that has been set by the circuit courts. It provides an indication of which sorts of jobs have been determined to be (non)equivalent based on the same factors (i.e., overlap of work behaviors, skill, responsibility, effort, and working conditions). Notably, just because a specific work behavior (or multiple work behaviors) has been determined as differentiating two jobs in one case does not mean it will automatically differentiate all jobs that differ on this work behavior. The concept of equal work is legally defined through the specific context (Brennan v. City Stores, 1973). For example, Brennan v. Prince William Hospital Corp. (1974) noted that in some medical contexts (e.g., specific nursing homes), catherization is required more frequently and is more difficult than in other contexts (e.g., other hospital units).

Table 2. Examples of substantially equal work under the EPA provided in the EEOC Compliance Manual (Section 10–Compensation Discrimination)

Table 3. Case law establishing substantially equal work under the EPA

Note. * = precedent summarized clarifies what makes two jobs equal. † = precedent summarized clarifies what makes two jobs unequal.

Examining trends in EPA rulings over time, Eisenberg (Reference Eisenberg2010) concluded that many courts have increasingly ruled that the comparator jobs identified by plaintiffs are not meeting the substantially equal standard, making it challenging for employees to successfully prove sex-based pay discrimination. However, the EPA is not the only statute under which pay discrimination claims can be made, and other laws have been viewed as imposing somewhat different standards (allowing for broader across-job comparisons), such as Title VII.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

There is a wider variety of potentially tenable scenarios that could be litigated under Title VII compared with the EPA, as not all Title VII scenarios require the direct comparison of jobs (EEOC Compliance Manual, 2000). Indeed, the Supreme Court in County of Washington v. Gunther (1981) ruled that Title VII claims are not bound by the substantially equal work standard of the EPA. However, the most common Title VII pay discrimination scenario begins like an EPA case, with an employee comparing themselves to another employee of the opposite sex (EEOC Compliance Manual, 2000). Multiple circuit courts have established that the prima facie burden in such a scenario is the same as under the EPA: proof that the work performed by the two employees is substantially equal (EEOC v. Maricopa County Comm. College Dist., 1984; Korte v. Diemer, 1990; Tenkku v. Normany Bank, 2003; Tomka v. Seiler Corp., 1995). However, the majority of circuit courts have opined that Title VII cases should instead follow the McDonnell-Burdine disparate treatment process when comparing these employees (Gutman et al., Reference Gutman, Koppes and Vodanovich2011). This means that, to begin a pay discrimination case under Title VII, instead of using a substantially equal standard to compare the work performed, the comparison is whether the employees being compared are similarly situated, which many courts have acknowledged to be more lenient than the substantially equal standard (e.g., Miranda v. B. B. Cash Grocery Store, Inc., 1992; Sims-Fingers v. City of Indianapolis, 2007).

In the first phase of a McDonnell-Burdine disparate treatment scenario, plaintiffs must meet their prima facie burden, for which McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green (1973) originally established four criteria (Gutman et al., Reference Gutman, Koppes and Vodanovich2011). Niwayama v. Texas Tech University (2014) specifies how these rules apply to the compensation context: the plaintiff “(1) is a member of a protected class; (2) was qualified for the position she sought or held; (3) suffered an adverse employment action [e.g., plaintiff was underpaid]; and (4) was treated less favorably than another similarly situated employee outside the protected group.” Thus, according to the fourth criteria, plaintiffs must demonstrate that they are (or were) similarly situated to an opposite sex comparator who is (was) treated better than they are (were). In the second phase, the defendant must articulate a reason for the different treatment between these two similarly situated employees.Footnote 7 Finally, the third phase consists of the plaintiffs showing that the reason articulated by the defendant for the pay difference is pretext for discrimination (Tex. Dep’t of Cmty. Affairs v. Burdine, 1981).

To find proof for the first (prima facie) phase, EEOC investigators examine whether employees are similarly situated based on (a) job similarity and (b) other objective factors (EEOC Compliance Manual, 2000). Job similarity refers to whether the jobs “generally involve similar tasks [i.e., a common core of tasks], require similar skill, effort, and responsibility, working conditions, and are similarly complex or difficult.” The manual gives minimum objective qualifications (e.g., a required certification) as an example of other objective factors. Historically, Title VII’s prima facie requirements were not meant to be burdensome for plaintiffs, as it is meant only to remove the most obvious or common nondiscriminatory explanations for a difference in treatment between two employees (Tex. Dep’t of Cmty. Affairs v. Burdine, 1981). The EEOC Compliance Manual (2000) therefore describes job similarity under Title VII’s similarly situated standard as more relaxed than the EPA’s substantially equal requirement.

Courts have varied in their interpretation of similarly situated (both across jurisdictions and over time). Some courts have tended to employ a very narrow definition, requiring almost identical comparators, whereas others have allowed comparators to vary more widely (Lidge, Reference Lidge2002). Courts have also varied in the type of factors they consider when determining whether a plaintiff and a comparator are similarly situated. Common themes across various circuit courts are that similarly situated employees work under the same supervisor and that employees have the same job functions, responsibilities, or titles. For example, whereas the 11th Circuit Court found that a plaintiff established a prima facie by establishing job similarity to higher paid, opposite sex comparators in Miranda v. B. B. Cash Grocery Store, Inc. (1992), other courts have considered additional factors. This is illustrated by Warren v. Solo Cup Co. (2008), where the 7th Circuit determined that two employees were not similarly situated because the company paid the male employee more based on superior education and computer skills, even though these factors were not specified as necessary for the job.

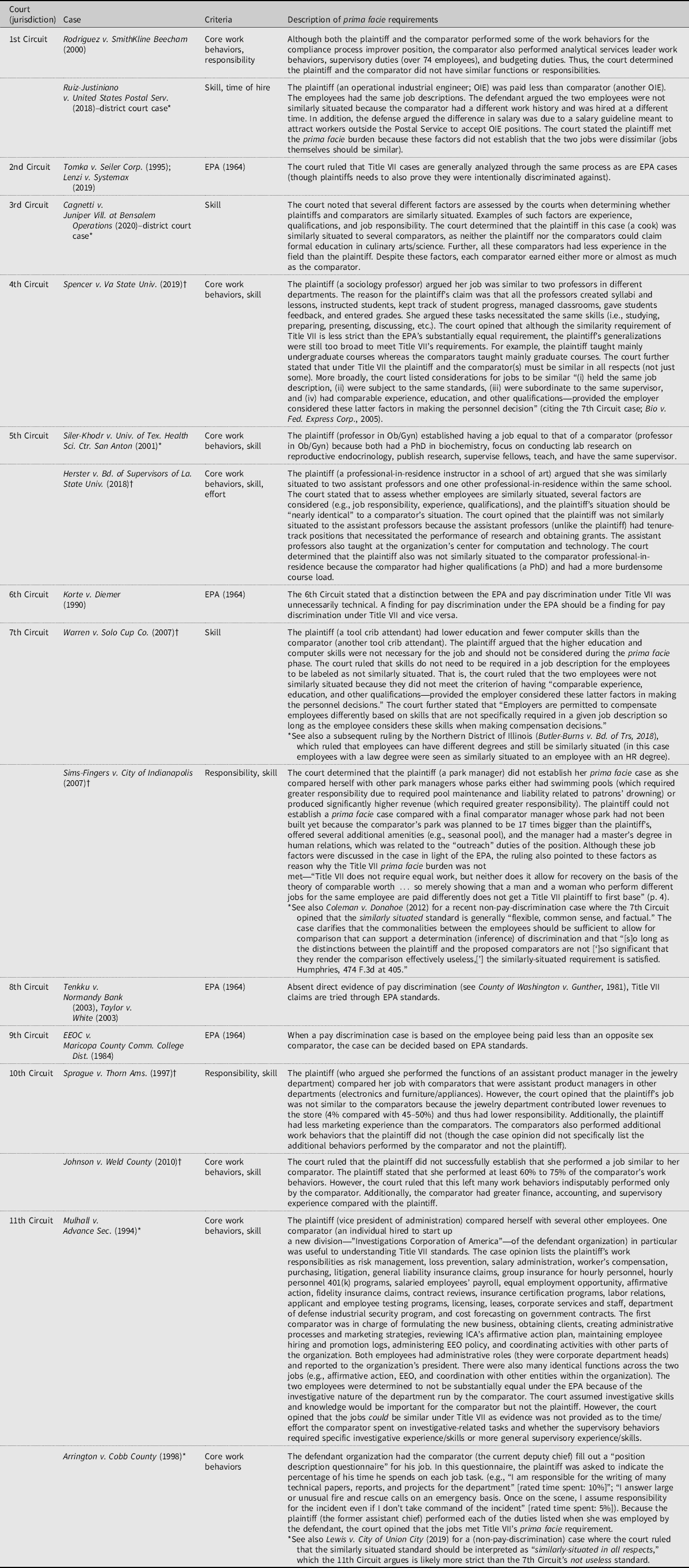

Additionally, the courts have varied in the criteria used to rule on whether employees are similarly situated depending on the context of the case. For example, precedent from the 6th Circuit notes that working under a different supervisor should only make employees not similarly situated if having a different supervisor holds reasonable relevance to the employees’ claim (e.g., in this context, the employee’s compensation; Bobo v. UPS, 2012). Table 4 provides a sample of pay discrimination rulings that illustrate what has been considered an appropriate comparator under the similarly situated standard under Title VII. We also point out cases where a circuit court has opined that a Title VII pay discrimination case should follow EPA (as opposed to McDonnell-Burdine) standards when the comparison of two or more employees is used to infer pay discrimination. Although the similarly situated employee standard of Title VII can include more criteria than the substantially equal work standard of the EPA, when describing methods for comparing employees and jobs later in this paper, we focus on the job similarity component of similarly situated (i.e., similar skill, effort, responsibility, working conditions, and complexity).

Table 4. Case law establishing similarly situated under Title VII pay discrimination cases

Executive Order 11246 (EO 11246)

The Federal Equal Pay Act and Title VII processes we describe above are typically initiated by an employee complaint. However, for organizations that are federal contractors or subcontractors, there are additional requirements as stipulated by Executive Order 11246. Specifically, the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP) proactively audits federal (sub)contractors using practices aligned with Title VII (OFCCP Directive, 2018). If the OFCCP determines that sex discrimination exists in an organization’s wages, it has the power to autonomously negotiate conciliation, requiring the organization to compensate employees that are discriminated against and ultimately revoke that organization’s ability to contract with the government if this conciliation fails. This process is particularly important to understand because the percentage of financial agreements that the OFCCP has secured that is related to pay discrimination has grown from 19% in the fiscal year of 2014 to 44% in 2017 (Colosimo et al., Reference Colosimo, Aamodt, Bayless and Patrick2018), suggesting this agency’s increased commitment to addressing wage discrimination. In the fiscal years of 2019 and 2020, the OFCCP announced several large settlements with major corporations that centered on pay discrimination ($7 million with Dell, just under $10 million with Goldman Sachs, $5 million with Intel Corp., and $9.8 million with JP Morgan Chase; Bachman & Krems, Reference Bachman and Krems2020; OFCCP, 2020).

The OFCCP has provided a directive wherein it describes its process for conducting pay audits (OFCCP, 2018). An OFCCP audit begins with the collection of data from the organization. Next, the OFCCP identifies pay analysis groups consisting of employees who are similarly situated for the purposes of the pay analysis. The OFCCP provides a definition for similarly situated employees as “those who would be expected to be paid the same based on: (a) job similarity (e.g., tasks performed, skills required, effort, responsibility, working conditions and complexity); and (b) other objective factors such as minimum qualifications or certifications.” Although this is similar to the EEOC’s definition of similarly situated (EEOC Compliance Manual, 2000), the OFCCP directive also notes that pay analysis groups may combine employees in different jobs or job categories, using statistical controls to ensure that workers are similarly situated. Then, a statistical model is used to examine whether sex predicts pay across this group of employees. Additional variables are added to the statistical model as controls (e.g., seniority) to ensure that the pay difference is only attributed to employees who are similarly situated. We discuss additional details on the manner in which these analyses are carried out below.

Because the OFCCP proactively audits organizations, there is no documented case law that allows us to examine examples of which jobs/employees do or do not meet the standard of similarly situated. However, Directive 2018-08 notes that the OFCCP will use an organization’s own job structure. This “assumes that the structure provided is reasonable, that the OFCCP can verify the structure as reflected in the contractor compensation policies, if necessary, and that the analytical groupings are of sufficient size to conduct a meaningful systemic statistical analysis” (OFCCP, 2018). Therefore, a job structure should reflect a reasonable categorization of jobs, based on documented evidence of job similarity.

State-level equal pay laws

Changes to state-level equal pay legislation have increased sharply in recent years (Nagele-Piazza, Reference Nagele-Piazza2018; Sheen, Reference Sheen2018), ranging from the banning of pay secrecy policies to limiting factor other than sex (FOS) defenses (e.g., allowing only FOS defenses that are job related).Footnote 8 Some states have updated their equal pay legislation by changing the terminology that is used to indicate which jobs should be compared. Indeed, many states have a history of using terminology that implies the comparison of a broader range of jobs in contrast to the federal EPA’s standard of substantially equal (Coil & Rice, Reference Coil and Rice1993). Specifically, 19 states reference comparable work/work of comparable character or similar/substantially similar work in their equal pay statues (Seyfarth, Reference Seyfarth2019). For some states, this terminology reflects a meaningful departure from the federal EPA standard of substantially equal work, whereas in other states, the difference in terminology appears to be surface level rather than a reflection of a meaningful difference in the underlying policy (see Table 5 provides select examples on exactly what may constitute equivalent jobs under states that use terms such as similar and comparable).

Table 5. Example state legislation, case law, and guidelines pertinent to comparison standards for pay discrimination

State-by-state examples

Alaska

Alaska’s equal pay legislation has long required work be paid equally when it is of comparable character. However, the Supreme Court of Alaska clarified that comparable character should be interpreted as the same as substantially equal (Alaska State Comm’n for Human Rights v. Department of Admin., 1990). That is, language indicating work of a comparable character versus substantially equal work is not thought to reflect an underlying difference in how jobs are compared under Alaska law.

Massachusetts

The Massachusetts Equal Pay Act (MEPA) has also required work be paid equally if it is comparable. Recently, the MEPA was amended, and the state’s attorney general published guidelines specifying how to interpret the MEPA’s comparable work standard (Office of the Attorney General, 2018). The MEPA defines comparable work as: “substantially similar skill, effort, and responsibility, and is performed under similar working conditions” (p. 5). However, unlike the standard set within Alaska, Massachusetts’s guidance specifies that comparable work is more inclusive (i.e., broader) than the federal EPA’s standard of substantially equal. It further gives examples of what jobs would and would not be considered similar (based on skill, effort, responsibility, and working conditions; see Table 5).

There are some other apparent differences between the federal EPA and MEPA. For example, under the MEPA, the term responsibility seems to encompass the job’s work behaviors themselves in addition to the amount of accountability the job holds. The Office of the Attorney General (2018) gives an example that sweeping floors may constitute a responsibility that differentiates two jobs, but not if the employee is only occasionally asked to sweep. In this way, responsibility is seemingly used in place of the federal EPA’s significant overlap in core work behaviors criterion. Additionally, unlike the federal EPA, the MEPA views the day or time of a shift as a working condition.

Oregon

The 2017 Oregon Equal Pay Act amendment requires equal pay for work of a comparable character, which “includes substantially similar knowledge, skill, effort, responsibility and working conditions” (Office of Secretary of State, 2018). A final rule published in 2018 by Oregon’s Office of Secretary of State gives examples of the types of factors considered in skill (e.g., ability, agility, creativity, experience), effort (e.g., physical/mental exertion, sustained activity, job task complexity), responsibility (e.g., accountability/discretion, significance of job tasks), and working conditions (e.g., time of day worked, physical surroundings, distractions, hazards). However, specific contextualized examples of these criteria are not given. Previous rulings in Oregon have explicitly noted that work of comparable character is a broader standard than both equal work and substantially similar work (Bureau of Labor & Industries v. Roseburg, 1985; Smith v. Bull Run School Dist., 1986).

California

California recently changed its terminology regarding the standard by which work should be evaluated. In 2015, the California Fair Pay Act (CFPA) set the standard as substantially similar as opposed to the previously used equal (Department of Industrial Relations, 2019). Additional guidelines for this law are listed by the California Commission on the Status of Women and Girls (2020). The CFPA lists criteria similar to those listed in the EPA (skill, effort, responsibility, working conditions, and a common core set of tasks). Differences in tasks argued to render jobs dissimilar should not be trivial, occasional, or comprise an unimportant amount of time from the employee. This guidance also gives specific examples for identifying (dis)similar jobs (see Table 5). Citations supporting these examples reference both federal EPA rulings as well as the OFCCP’s standard for similar work. Additionally, some of the specific examples given are similar to the examples given by the EEOC Compliance Manual for which jobs would be substantially equal under the EPA. Therefore, it remains unclear exactly how different California’s substantially similar work standard is from the substantially equal work standard, the work of a comparable character standard, or the similarly situated employee standard.

Summary

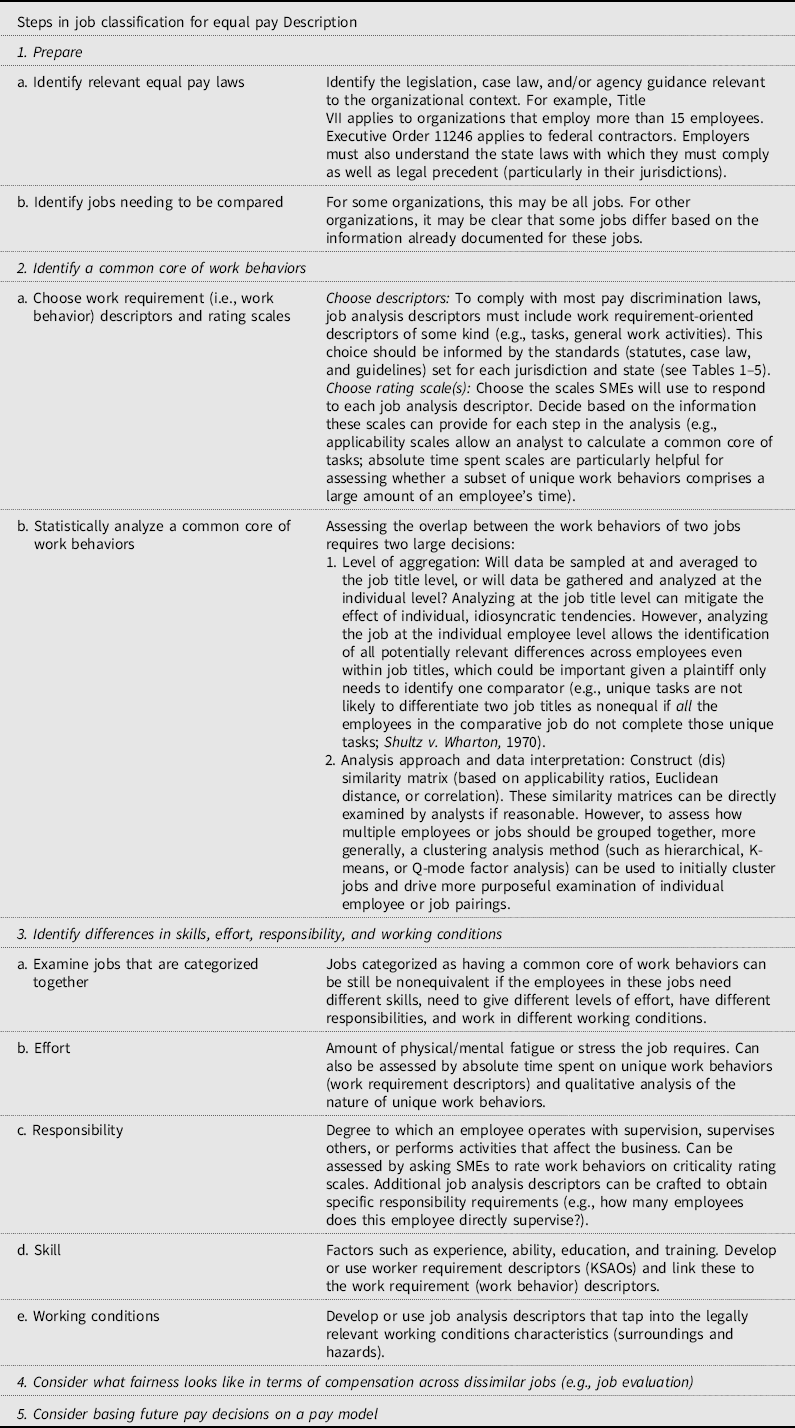

Overall, this summary of various federal and state statutes, as well as case law and compliance guidelines relevant to equal pay (see Tables 1–5), highlights the necessary considerations for identifying equivalent versus nonequivalent jobs according to varying legal standards and jurisdictions. To reiterate, our goal was not to provide an exhaustive review of every law and precedent that has relevance to pay discrimination, but rather to give a broad sample of the types of criteria that need to be considered when building and studying HR systems that accommodate pay equality.Footnote 9 With this information in mind, we next discuss the specific methodologies that can be used to systematically and reliably categorize numerous jobs within large organizations based upon both scientific and legal criteria. In the next section, informed by our legal review, we discuss how job analysis and job classification can be used to provide evidence of job (in)equality, (dis)similarity, or (non)comparability.

Job analysis and classification for identifying jobs that require equal pay

Job classification refers to a bottom-up method for categorizing jobs into groups (Morgeson et al., Reference Morgeson, Brannick and Levine2019). This method relies on the judgement of subject matter experts (SMEs) on the jobs in question (e.g., current employees, supervisors, job analysts). The simplest job classification strategy is to ask subject matter experts to holistically decide how similar an entire job is to another job. A more systematic strategy categorizes jobs based on the information gathered during a job analysis, where work and worker characteristics are identified such as work requirements (i.e., work behaviors such as job tasks or duties), worker requirements (i.e., knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics [KSAOs]), and/or work contexts (e.g., social and physical variables that influence and contextualize work; Morgeson & Dierdorff, Reference Morgeson, Dierdorff and Zedeck2011). These characteristics can be assessed by asking SMEs to rate job analysis descriptors (i.e., items that contain work or worker characteristics) on scales such as applicability, importance, frequency, absolute or relative time spent, level required, and criticality (Gael [Reference Gael1983] suggests using applicability, importance, criticality, and time spent when applying job analysis to job classification). These ratings can then be compared through the judgements of experts or more systematically by applying statistical methods to categorize jobs that have rating profiles that are similar (e.g., using clustering-based methods to identify jobs where SMEs have largely endorsed [and endorsed to the same extent] the same job analysis descriptors).

Interestingly, the holistic ratings of similarity between pairs of jobs (i.e., where SMEs are simply asked to determine how similar two jobs are) and statistical clustering methods (i.e., where jobs are grouped based on similarity of SME ratings across various job analysis descriptors) can result in the same general classifications of jobs (Sackett et al., Reference Sackett, Cornelius and Carron1981). Yet ratings capturing the extent to which SMEs generally believe two jobs are equivalent do not provide evidence of the specific common and differentiating characteristics between jobs, which is needed to establish job equivalence within a legal context. For example, in the 3rd Circuit EPA case Shultz v. Wheaton (1970), the organization attempted to argue that male selector-packers needed to be more flexible than female selector-packers to perform extra work, which comprised 16 additional tasks. The court noted that the average percentage of time that male selector-packers spent on these extra tasks was not provided. Furthermore, the court determined that there was no evidence that all male selector-packers performed or, in fact, needed to be available to perform these extra tasks, concluding that the difference between male and female selector-packers was artificial. Other courts have similarly noted a lack of evidence concerning the amount of time comparators spent performing additional tasks and whether all the comparators actually performed these additional tasks (Hodgson v. Daisy Mfg. Co., 1971; see EEOC v. Port Auth. of N.Y. and N.J., 2014 for an example where the plaintiffs failed to provide sufficient information regarding actual job content to demonstrate jobs were substantially equal).

These rulings demonstrate the need for systematic, documented evidence of the work employees complete (in addition to other job-related characteristics such as the skills required by a job). Job analysis and job classification can provide such a basis for organizations to systematically determine which jobs are (non)equivalent.

Although the human resource management literature notes the usefulness of job classification for developing pay systems (e.g., Harvey, Reference Harvey1986), it has not yet considered or integrated the legal criteria for pay discrimination into job analysis or job classification methods. That is, it has not specifically considered what needs to be done to make job analysis and job classification relevant to determining substantially equal work, similar work, or work of comparable character. Job analysis and job classification should be considered in light of these legal standards because these methods can be completed in several different ways (and can apply different rules for interpretation; Morgeson et al., Reference Morgeson, Brannick and Levine2019), many of which would not be helpful for determining pay discrimination.

Using job analysis and job classification to categorize equivalent jobs

As we discuss above, the EPA, Title VII, EO 11246, and many state-level equal pay statutes refer or allude to (a) a common core of work behaviors across the jobs and (b) the skills, effort, or responsibilities the jobs require or working conditions under which the jobs are performed. Thus, we can use these criteria to build a general job analysis and job classification procedure for identifying equivalent jobs. Specifically, we discuss below how job analysis/job classification descriptors, rating scales, and analytic approaches can be used to assess each of these criteria.

Although we suggest a general approach that is appropriate for the pay equality context, organizations should customize their approach (e.g., their job analysis descriptors, response scales, and decision rules for interpreting job classification results) based on the specific laws, precedent, and regulations to which they are accountable (as well as their specific organizational context). We also note that the statistical analyses we suggest below (e.g., cluster analysis) are not required to successfully defend two jobs as being nonequivalent, though several courts have demonstrated an interest in basic statistics such as the percentage of overlap of work behaviors across two jobs (see Tables 3 and 4). That being said, the approach we present allows for the systematic, proactive categorization of numerous jobs, which would likely improve an organization’s ability to not only defend itself when legally challenged but also mitigate the risk of legal challenge by increasing the fairness of pay systems.

Identifying a common core of work behaviors

Choosing work requirement descriptors (tasks vs. generalized work activities)

A common core of work behaviors across jobs can be assessed using work requirement job analysis descriptors. However, work requirements can be crafted at different levels of abstraction (tasks vs. generalized work activities). Therefore, it is important to consider which level of abstraction is appropriate.

In the job analysis literature, tasks describe relatively specific work behaviors (Morgeson & Dierdorff, Reference Morgeson, Dierdorff and Zedeck2011). These tasks are generally thought to provide adequate specificity if they refer to a complete task and if breaking the task down further would result in a description of individual movements (Morgeson et al., Reference Morgeson, Brannick and Levine2019). For example, statements along the lines of “turn on register” and “call customer to register” would likely be too specific to be helpful or practical. Appropriate task descriptions have been described by Fine and colleagues as including several elements: the action being completed (i.e., an action verb), the object of the task, and the output or goal of the task (Fine & Cronshaw, Reference Fine and Cronshaw1999; Fine & Getkate, Reference Fine and Getkate1995).

Potential additional elements include what sources of information employees use or what tools or equipment the employees use. However, there is even variance in abstraction among task statements. Inductively developed task inventories for a specific job allow the greatest opportunity for a low level of abstraction (Morgeson et al., Reference Morgeson, Brannick and Levine2019). That is, job analysts can write tasks for individual jobs with great specificity based on data that are gathered from observations, interviews, and/or previously developed job materials. These can be compared with the often more abstract tasks that have been included in established/off-the-shelf job analysis inventories. Examples of more abstract tasks can be found within the O*NET system (www.onetonline.org). As with off-the-shelf measures, these tasks are necessarily more general than the tasks that are typically developed via local job analyses. For example, the tasks that O*NET lists for lawyers apply across multiple areas (e.g., criminal law, patent law) and work contexts (e.g., across different types of firms).

In contrast to tasks, generalized work activities describe work behaviors at a moderate or medium level of abstraction (Gibson, Reference Gibson, Wilson, Bennett, Gibson and Alliger2012).Footnote 10 Research using the work dimension analysis technique has developed a pool of items (generalized work activity descriptors) that, when assessed in combination, are thought to describe a wide variety of jobs. Gibson (Reference Gibson, Wilson, Bennett, Gibson and Alliger2012) gives examples of the difference between typical task inventory descriptors and generalized work activity descriptors. A task descriptor might be “visually inspect newly cut diamonds for flaws without magnification aids,” whereas an example of the same work behavior represented as a generalized work activity is “see small details of close objects” (p. 216). These generalized work activity items can be analyzed in their own right or aggregated into dimensions with even greater abstraction (e.g., “use sight and visual information” or “getting information,” p. 216), depending on the intended use of the data. Several validated, generalized work activity analysis tools exist, each with different strengths and weaknesses and even varying levels of descriptor abstraction (e.g., Position Analysis Questionnaire, McCormick et al., Reference McCormick, Jeanneret and Mecham1972; Job Element Inventory, Cornelius & Hakel, 1978; O*Net GWAs; Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Mumford, Borman, Jeanneret, Fleishman, Levin, Campion, Mayfield, Morgeson, Pearlman, Gowing, Lancaster, Silver and Dye2001).

When choosing the level of abstraction for work requirement descriptors (i.e., work behaviors), organizations should consider three major factors, which we discuss in turn below: (a) allowance for jobs to be compared, (b) consistency with applicable case law, and (c) feasibility for the organization.

Do the descriptors allow for comparisons across jobs of interest?

In order to statistically categorize jobs, data are needed on all of the jobs that are being compared. In other words, SMEs across all of the jobs of interest must rate the same set of job analysis descriptors. Although using task descriptors (the lowest level of abstraction) gives the job analyst a concrete, specific picture of the work employees complete, it narrows the number of jobs that can be simultaneously compared. To conduct a job classification analysis, the tasks that are developed for all of the jobs that are being assessed need to be combined into one job analysis survey. If very specific job tasks have been developed for many jobs, combining all of these tasks together would likely result in an impractically lengthy survey. Further, the more specific the work requirement descriptors, the less likely any specific descriptor would apply to multiple jobs or employees and the more likely that SMEs from different jobs filling out one job analysis survey would indicate many tasks as being irrelevant.

In contrast, assessing general work activities allows for the identification of similarities across a wider variety of jobs without demanding that SMEs fill out excessively long surveys. Following our example above, more jobs require employees to “see small details of close objects” rather than to “visually inspect newly cut diamonds for flaws without magnification aids.” Therefore, a wider variety of jobs would be grouped together during a job classification with more abstract descriptors. However, too high a level of abstraction will preclude the courts from understanding the behaviors required by different jobs. Thus, determining the appropriate level of abstraction is crucial.

What specific legal precedent informs the choice of work requirement descriptors?

The terms that are generally used in the legal literature to describe the common core of work behaviors do not clearly elucidate which level of abstraction is appropriate when choosing job analysis descriptors. Even though the EEOC Compliance Manual refers to a common core of tasks when describing federal EPA criteria, in the legal literature, it appears that tasks are often used synonymously with duties. In the same vein, the word responsibility is often used to describe the nature of work behaviors (i.e., how much responsibility a job task requires) rather than a specific level of abstraction for work behaviors (EEOC, 2000), whereas at other times it appears to be used as a synonym for work behaviors. Despite this ambiguity in terminology, the legal literature can still guide the choice of appropriate work requirement descriptors through the precedent set by specific cases.

As we discussed above, the circuit courts vary in how “strict” they are in comparing jobs under both Title VII and EPA standards, which is likely to have important implications for the levels of abstraction that each court finds appropriate. Case law can give examples of the appropriate level of abstraction for each legal standard (e.g., substantially equal, similarly situated) within each jurisdiction. For example, the DC Circuit Court ruled in Thompson v. Sawyer (1982) that bindery workers who worked on a Smyth sewing machine performed substantially equal work to bookbinders who worked on other bookbinding machines. The court noted that both bindery workers and bookbinders performed the common work behaviors of “gluing, stitching, cutting, and putting together the parts of a book.” Additionally, both jobs involved creating the inside of a book, folding signatures, cutting signatures, and making the cover and inside of the cover. The court gave the contrasting example that driving two machines may be very different if the machines are a truck versus a tugboat. This highlights just how much care must be placed on not only the level of abstraction used in developing descriptors but also on the specific context of the organization and jobs within it.

In a 2nd Circuit Court Case, EEOC v. Port Auth. Of N.Y. & N.J. (2014), the court found the descriptors that were used to be too broad and not sufficient for demonstrating whether the jobs of different attorneys were substantially equal. Instead, the court stated that it would want to see “whether the attorneys handled complex commercial matters or minor slip-and-falls, negotiated sophisticated lease and financing arrangements or responded to employee complaints, conducted research for briefs or drafted multimillion-dollar contracts.” This level of specificity would not be present in generalized work activities, nor would it be present in the tasks that are specified for lawyers on O*NET. Thus, differentiating lawyers under this 2nd Circuit Court standard would likely require a fairly specific, inductively built task inventory.

Overall, based on the relevant legislation, case law, and regulatory guidance within a jurisdiction, organizations might choose different levels of abstraction for their work requirement descriptors. However, the relevant laws are not an organization’s only concern when choosing this level of abstraction. For example, organizations that adopt a more abstract approach (or a more specific approach) may find that employees perceive there to be meaningful differences between jobs that are categorized as equivalent and deserving of the same pay (or that jobs are differentiated based on, in their opinion, criteria that are too specific to be meaningful). Either of these scenarios could potentially result in negative fairness perceptions (i.e., distributive injustice) that, in turn, can lead to negative employee job attitudes and behaviors (Rupp et al., Reference Rupp, Shao, Jones and Liao2014). Ultimately, organizations must carefully determine the level of abstraction most appropriate for their specific context.

Is the collection of optimal descriptor data across all jobs feasible?

Organizations should also consider how they can realistically assess jobs for equivalence. Inductively building job analysis descriptors that are unique to each job in a particular organization can be time consuming and expensive. Off-the-shelf tools for assessing generalized work activities are relatively inexpensive and easy for employees to complete (although they can be quite long). However, as mentioned above, organizations may not find the information that is collected using these off-the-shelf tools specific enough to document the criteria that can be reasonably used to differentiate jobs under the EPA, Title VII, EO 11246, or state-level equal pay laws. Thus, organizations must carefully weigh what is appropriate and feasible in their specific context. Some organizations may benefit from first conducting a job classification by using an established generalized work analysis survey. Next, task inventories with more specific task descriptors (developed at an appropriate level of abstraction for the context) could be inductively developed, given to employees within these broader groups, and used for a secondary job classification. This process would first allow for the identification of potentially equivalent jobs, which could then be investigated more thoroughly.

Choosing rating scales and ratings sources

Once appropriate descriptors are chosen to assess work behaviors, response scales must be chosen on which these descriptors can be rated by SMEs. These rating scales should be selected to ensure the resulting data can reveal whether two jobs share a common core of work behaviors. Within litigation contexts, evidence of such a common core has been presented in some cases via the percentage of behaviors that are the same or different across jobs (e.g., Johnson v. Weld County, 2010; Keller v. Crown Cork & Seal USA, Inc., 2012). This percentage of overlap can be proactively assessed across jobs by using applicability scales (e.g., 0 = this task does not apply to the job; 1 = this task applies to the job). Alternatively, evidence suggests that some courts may consider the percentage of time that employees spend on common or unique work behaviors (e.g., see case opinions of Shultz v. Wheaton Glass Co., 1970; Usery v. Allegheny County Institution Dist., 1976). This suggests that classifying jobs into groups based on the absolute time spent on different activities could also help to determine a common core of work behaviors.Footnote 11 However, other courts have instead explicitly used the amount of time that employees spend on extra work behaviors to evidence extra effort (rather than a noncommon core of behaviors; see below for discussion on evaluating effort of unique behaviors).

Other rating scales could also be used to assess the overlap of work behaviors between two jobs (e.g., importance, frequency). Although information from these scales could be used to statistically group employees, they do not translate to specific metrics that are mentioned in the court decisions that we have reviewed, and thus there appears to be less precedent to guide an organization’s interpretation of such analyses. Indeed, the 4th Circuit Court has even specifically opined that differences in how frequently two different employees perform the same routine behaviors does not indicate differences in skill, effort, or responsibility, determining that the two employees can still therefore perform substantially equal jobs (Brennan v. Prince William Hosp., 1974). This ruling could also have important implications for the careful use of time spent scales. That is, those who are interpreting time spent data might want to ensure that employees that are determined to differ in their core of work behaviors do not simply allocate different amounts time to the same routine tasks.

Legal precedent around particular scales should also be weighted alongside what is known about the statistical and psychometric properties of the various scales (see Duvernet et al., Reference DuVernet, Dierdorff and Wilson2015, for a discussion of interrater agreement, and both inter- and intrarater reliability of job analysis survey ratings) as well as potential biases they might create. For example, the ratings stemming from a number of different job analysis scales have been shown to be significantly correlated (cf. Sanchez & Levine, Reference Sanchez and Levine2012), meaning that although different in theory and practicality for communication purposes in a court setting, not all rating scales may be meaningfully different in terms of how employees actually use the scales to rate job analysis descriptors.

Finally, the sources of SME job analysis ratings should be considered in light of their benefits and drawbacks (Morgeson & Dierdorff, Reference Morgeson, Dierdorff and Zedeck2011). Job incumbents have the most intimate knowledge of the job in question. However, they may not sufficiently understand the goals of a job analysis or may be motivated to lower or inflate their ratings in order to “game the system” in a way that will ultimately favor themselves or their work unit. Supervisors might better understand the goals of a job analysis and be less motivated to inflate ratings but often have less detailed knowledge on the job as it is performed currently. Job analysts are best positioned to understand the goals of a job analysis and provide reliable ratings but also might not have the level of job knowledge necessary to provide accurate ratings. Not only are these vulnerabilities important to consider simply from the standpoint of wanting accurate job analysis information, but any scientific evidence pointing to bias or inaccuracy in a particular method could also be used to argue that a defendant organization’s expert testimony/methodology should be discredited in court or not admitted altogether (Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals Inc., 1993).

Statistically analyzing the common core of work behaviors

Once work requirement descriptors and rating scales are chosen and data collected from SMEs, statistical methods can be used to systematically assess the extent to which work behaviors are shared across jobs. This can inform an organization’s decision on whether the jobs of interest do or do not have a common core of work behaviors. Basic descriptive statistics can be used to analyze the similarity between any two jobs (e.g., the percentage of job tasks that are required by both jobs).Footnote 12 Such similarity indices can also serve as the basis for more complicated statistical analyses that simultaneously consider data pertaining to multiple jobs, such as cluster-analysis methods. Whereas the data analysis methods that are most familiar to organizational researchers tend to focus on relationships among variables, cluster analysis is object or person oriented (Woo et al., Reference Woo, Jebb, Tay and Parrigon2018) and thus focuses on similarities among people or jobs to derive clusters of people/jobs that are similar within a cluster and distinct between clusters.

Harvey (Reference Harvey1986) reviews cluster methods that are commonly used within job classification, dividing methods into descriptive and inferential approaches. Descriptive clustering methods group employees or jobs based on observations of the current data, whereas inferential clustering methods focus on the probabilities that a case (i.e., each employee or job) belongs in a group based on the likelihood that the differences and similarities among job groupings would be consistently found among the broader population of people or jobs.

Within a pay equality context, the question becomes whether a descriptive or inferential approach is more useful for determining which jobs can be grouped together by virtue of sharing a common core of work behaviors. The EEOC Compliance Manual (2000) defines this common core as “a significant portion of tasks”; however, the phrase appears to refer not to statistical significance but rather to whether the proportion of overlap in the work behaviors performed (or perhaps even the amount of time employees spend on the same work behaviors) is large enough to be considered meaningful by a court (see Tables 2, 3, and 4). It can be argued that descriptive methods are more appropriate for job classification in this context because they allow for the categorization of available/current employees or jobs within a specific organization (rather than drawing inferences about differences among job classes in a general population).Footnote 13 Therefore, we focus on methods without a significance test.

Clustering methods begin by constructing an employee × employee (or job × job) matrix of similarity or dissimilarity, where each pair of employees (jobs) is represented by a number that symbolizes similarity or dissimilarity between the two employees (or jobs; Aldenderfer & Blashfield, Reference Aldenderfer and Blashfield1984). There are two important factors to consider when constructing and analyzing this matrix: (a) how data are aggregated and (b) the analytic and interpretive approach that is applied.

Data aggregation

Although job analysis ratings from individual employees can be analyzed, it is common to treat employees within the same job title as equivalent for the purpose of pay equality analyses (Sady & Aamodt, Reference Sady, Aamodt, Morris and Dunleavy2017). Therefore, the organization might choose to average data from employees within a job title and then conduct analyses on similarity among different titles. Additionally, organizations that find it impractical to gather this volume of data from all incumbents may instead employ a sampling approach where a smaller sample of employees’ scores is averaged to represent all the employees in a job title. When sampling is used, care should be taken that the sample is representative of the relevant employee population in terms of employee characteristics (e.g., demographics, experience; Landy & Vasey, Reference Landy and Vasey1991) and work contexts (e.g., location, work shift, etc.).

Job analysis ratings by an individual employee will represent both characteristics of their jobs and person-specific information about the individual’s work assignments and their perceptions of those requirements. Other individual differences, such as difference in response tendencies, may exist as well, which can introduce measurement error (Cranny & Doherty, Reference Cranny and Doherty1988). Averaging across all respondents within the same job title can provide more reliable data at the title level. However, this can also obscure real differences in the jobs performed by these individuals, leaving untested the assumption that all employees working under the same job title are performing equivalent jobs (see Strah, & Rupp, Reference Strah and Ruppin press). Aggregation that obscures real differences between the jobs of employees within the same job title can be problematic for organizations because potential plaintiffs only need to identify one (opposite sex) comparator who performs equivalent work but is paid more to launch a pay discrimination case.

The choice of aggregation approach should be aligned with the goal of the analysis. If the goal is to determine what job titles can be considered equivalent, then data from multiple incumbents within each title can be averaged prior to analysis so that each data point represents a distinct job. However, if job titles are extremely varied, or if there is a question regarding whether individuals who work under the title are truly working equivalent jobs, then a person-level analysis would be preferred.

If data are to be averaged, it is important to assess within-job agreement and interrater reliability (Duvernet et al., Reference DuVernet, Dierdorff and Wilson2015; Lindell & Brandt, Reference Lindell and Brandt1999), as low agreement and reliability can compromise any statistical analysis that is performed on job analysis data. If agreement is low, an individual-level analysis may be more appropriate. Alternatively, the statistical methods described below could be applied to employees within a single title to identify multiple subgroups, which could then be treated as distinct jobs in subsequent analyses. Further, all job analysis tools that are used should have sufficient intrarater reliability (assessed though repeated items in the same survey or repeated administrations of the same survey). Dierdorff and Wilson (Reference Dierdorff and Wilson2003) provide average reported (inter- and intrarater) reliabilities of job analysis ratings across different data sources, scale types, job analysis descriptor numbers, and number of raters.

Analysis approach and data interpretation

When clustering binary variables (e.g., applicability scales; 0 = I do not complete this task; 1 = I complete this task as a part of my job), a similarity matrix can be constructed using the frequencies of the number of work behaviors on which employees overlap (Řezanková & Everitt, Reference Řezanková and Everitt2009). As an example, consider a scenario where the results of a job analysis survey show that two employees (employee A and employee B) indicate that they perform 20 of the same tasks (both rate tasks as “1”) and do not perform 30 of the same tasks (both rate these tasks as “0”). Next, employee A endorses performing 10 tasks that employee B does not perform (employee A rates these tasks as “1,” whereas employee B rates these tasks as ‘0’), and employee B endorses performing 10 tasks that employee A does not perform (employee A rates these tasks as “0,” whereas employee B rates these tasks as “1”). In this example, the frequency of overlap between employee A’s tasks and employee B’s tasks can be calculated as a frequency ratio of symmetric variables—(20 + 30)/(20 + 30 + 10 + 10)—which results in a 71% overlap. It can also be calculated as a frequency ratio of asymmetric variables, known as the Jaccard coefficient, or (20)/(20 + 10 + 10), which results in a 50% overlap. In this second example (asymmetric), behaviors that both employees indicate are not relevant to their job (rated as “0”) are not included in the equation, which aligns with what most might assume this frequency index represents. That is, theoretically, there could be an almost unlimited number of work behaviors that any two employees do not perform, and including all these irrelevant behaviors would inflate all the numbers in the similarity matrix.

When the item/descriptors are work behaviors that are rated on nonbinary scales such as time spent (absolute or relative), frequency, or importance, (dis)similarity is often operationalized using Euclidean distance (the square root of the sum of squared differences on each task; Aldenderfer & Blashfield, Reference Aldenderfer and Blashfield1984). An alternate measure of similarity is the correlation between the ratings made about two jobs. This is not a typical correlation, which quantifies the linear relationship in the pattern of responses to two variables across multiple observations. Instead, the data matrix is flipped on its side, and the correlations represent the degree of relationships between the responses made about two jobs across multiple items. An important distinction between Euclidean distance and correlation is that correlation only captures the similarity of the pattern of responses and ignores differences in elevation (e.g., if one observation tends to have higher ratings across all work behaviors). In contrast, distance measures capture both pattern and elevation. Garwood et al. (Reference Garwood, Anderson and Greengart1991) suggest that correlation and distance measures are sensitive to different types of job similarity, so it can be useful to use both approaches and compare results. We note that unlike the percentage of overlap in work behaviors we described above, operationalizing (dis)similarity between employees or jobs using Euclidean distances or correlations does not always provide clear and easy-to-communicate answers within a litigation context. That is, the values that represent the (dis)similarity between two jobs when Euclidean distances and correlations are used are not as intuitively meaningful as the more straightforward percentage of overlap.

These similarity matrices give a preliminary indication of whether employees share a common core of work behaviors. For example, if two employees perform almost all of the same behaviors, this would suggest that the employees have a common core of work behaviors (see Tables 2, 3, and 4 for examples of the extent to which work behaviors might need to overlap for jobs to be considered equivalent). Perusal of this matrix allows analysts to individually assess the overlap of work behaviors between each pair of employees (or jobs). However, examining an entire similarity matrix can be challenging if many employees (or jobs) are included. Thus, it can be beneficial to group similar employees (or jobs) together and evaluate similarity across employee or job groups (i.e., clusters) rather than across individual employees or jobs.

Cluster analysis seeks to model the underlying categorical structure of a collection of jobs or employees, group similar employees/jobs together into clusters, and reveal the hierarchical structure of employee/job clusters and differences among them. This broader picture of the structure of jobs is helpful in the design of compensation systems, ensuring that job classifications are aligned with the empirical similarities and distinctions among these jobs. Cluster analysis can also be used to evaluate whether an organization’s classification system is similar to the one that emerges inductively, confirming or challenging whether the current classification system is appropriately differentiating jobs.

Several approaches to clustering objects have been developed, each with advantages and disadvantages (Harvey, Reference Harvey1986). In a hierarchical cluster analysis, cases are grouped with other cases that are closest to them in the similarity matrix (Aldenderfer & Blashfield, Reference Aldenderfer and Blashfield1984). Clusters are built in a sequential fashion—at each stage, the two most similar individual employees/jobs or groups of employees/jobs are combined, and this repeats until all cases are in one large group (the reverse is also possible where the analysis starts with one large group and each step parses apart subgroups that are the least similar from each other within the larger group). The results can be summarized in an intuitive graphical display, the dendrogram, depicting the employees/jobs comprising each cluster along with the similarity of objects within and between clusters (see Figure 1). The benefit of this clustering technique is that it does not require the predetermination of a specific number of groups that might not fit the natural groupings of the data (Huang, Reference Huang1998). Instead, it allows the researchers to simultaneously inspect the composition of clusters at different levels of generality (e.g., you can easily see how a general class is divided into subgroups). This flexibility is also a disadvantage in that hierarchical analysis does not provide definitive groupings of employees that have a specific amount of overlap. Several statistical measures have been developed to aid in determining the number of clusters (e.g., the change in within-cluster variance, or the between-to-within cluster ratio; Milligan & Cooper, Reference Milligan and Cooper1985), but it ultimately comes down to the judgement of the analyst.

Figure 1. Dendrogram representing the results of a hierarchical cluster analysis

Unlike hierarchical clustering, K-means clustering starts with a specified number of clusters and sorts objects into these clusters based on their similarity (Euclidean distance) from the midpoint of each cluster. A disadvantage of this approach is that the analyst must specify the number of clusters in advance (Huang, Reference Huang1998). However, this limitation can be overcome by running the analysis with differing numbers of clusters and then choosing the best solution by applying the same criteria as in a hierarchical analysis. K-means clustering is more computationally efficient when there are many positions to be analyzed. Additionally, it provides a profile (centroid) for each cluster, which can be used to classify new positions not included in the original analysis.

Another clustering method is Q-mode factor analysis (Ross, Reference Ross1963). This differs from traditional factor analysis because it derives factors not from groups of similar variables but from groups of similar objects. The resulting factors can therefore be considered as clusters of employees or jobs that have a similar pattern of high and low ratings across work behaviors (Harvey, Reference Harvey1986). Employees/jobs that load highly on the same factor can be assumed to be similar from a statistical standpoint. An advantage of the Q-mode analysis is that it allows positions to load on multiple factors, unlike hierarchical analysis, which assigns an object to one and only one cluster. This allows the analysis to capture additional complexities in the structure of jobs, although it also comes with increased complexity in interpreting the results. An extension of this approach is two-mode factor analysis (Cornelius et al., Reference Cornelius, Hakel and Sackett1979), which simultaneously factors both tasks and employees (or jobs), yielding multiple clusters, each with a distinct profile of task factors.

Hierarchical and Q-mode clustering are both purely exploratory approaches and may yield job groupings that are inconsistent with the organization’s current system of job titles. On one hand, this is a way for organizations to scrutinize their current system of classifying jobs by comparing their current job structure to a structure that emerges inductively based on (and is interpreted in light of) relevant established legal criteria. At the same time, the organization would need to have a plan established to address any results showing classifications that differ from the existing structure. Technically speaking, another approach might be to employ the option within K-means analysis that allows for the seeding of categories with expected job profiles, making the approach somewhat more confirmatory than explanatory. However, using such an approach might also, to some extent, limit opportunities to find discrepancies in the current system (e.g., jobs that are not classified together but should be).

Given the strengths and weaknesses of each approach, there is no general preferred method for conducting a job classification analysis from a scientific standpoint (Harvey, Reference Harvey1986). Indeed, some researchers have suggested that if the same item descriptors are used, different statistical techniques will yield similar clustering results (Levine et al., Reference Levine, Thomas, Sistrunk and Gael1988). Others have suggested applying multiple methods (Garwood et al., Reference Garwood, Anderson and Greengart1991) or combinations of methods (Colihan & Burger, Reference Colihan and Burger1995) as appropriate depending on the particular sample and context. Additionally, a number of advances in cluster analysis from the machine-learning literature have become available in recent years (see e.g., Kassambara, Reference Kassambara2017). Although the utility of these newer methods has not yet been examined within the job analysis literature, they may provide additional tools to improve the accuracy of job classification.

Overall, these statistical techniques serve as a systematic first step in determining which jobs can be meaningfully categorized as demonstrating a common core of work behaviors. However, it is important to recognize that clustering methods focus on relative rather than absolute similarity. That is, clusters are formed because a the employees or jobs in a group are more similar to each other than they are to employees/jobs in other group. There is no guarantee that employees/jobs clustered together will be similar enough to be treated as equivalent by the court. Therefore, the results must be carefully examined and interpreted to ensure that jobs are categorized in a manner that is useful for determining fair and legally appropriate pay.

First, cluster analysis results should be carefully examined to determine whether groupings of employees/jobs (or, in a hierarchical analysis, at what point groupings of employees/jobs) are meaningful in terms of having a high overlap of work behaviors, as defined by the laws and precedent under which an organization is operating. The clustering analysis output provides a preliminary sense of where to begin investigating individual pairings (e.g., through an analyst’s direct appraisal of the similarity matrix or even the SME ratings of work behaviors for both jobs) to understand exactly how closely related employees/jobs are that are categorized within the same cluster. Legal precedent can direct attention to exactly how closely two employees/jobs should overlap in order to share a common core of work behaviors (based on indices such as the percentage of work behaviors that overlap or amount of time spent on the same work behaviors; see Tables 2, 3, and 4). Second, employees/jobs that have been categorized into separate groups but that still have a relatively high amount of overlap (or favorable Euclidean distance/high correlation) should be carefully reviewed. The individual job analysis descriptors that are rated differently across these two jobs should be double checked to ensure that the work behaviors represented in these descriptors (or differences in scale ratings) are not insubstantial in nature.

Importantly, there may only be one (or a small amount of) distinguishing work behavior(s) between two employees or jobs. However, these differences may still be meaningful enough to warrant a distinction of legally dissimilar or unequal. For example, two employees may share almost all of the same job tasks, but if the one additional task a comparator performs accounts for the majority of the comparator employee’s time, the defendant organization may have a convincing argument that the two employees perform nonequivalent jobs. Assessing both applicability and absolute time spent scales would allow organizations to assess the overlap of work behaviors across employees/jobs in both of these respects (percentage of work behaviors that overlap and the amount of time unique work behaviors comprise for employees). However, a qualitative analysis may still be necessary. Specifically, if SMEs feel that two jobs that have been grouped together are sufficiently different to warrant different pay, the specific descriptors that reflect the differences between the two jobs may need to be further clarified.

Identifying differences in skills, effort, responsibility, and working conditions

Once a common core of work behaviors has been established across two or more employees/jobs, organizations must assess whether the skills, effort, responsibility, or working conditions required make a job unique from a comparator job. Each of these criteria can be investigated using job analysis and (sometimes) job classification approaches.

Effort

Effort refers to the amount of physical or mental fatigue or stress that is required for work behaviors. Importantly, two jobs can still be equal if their different work behaviors require the same amount (but not necessarily the same kind) of effort (EEOC Compliance Manual, 2000). In Hodgson v. Brookhaven (1970), the 5th Circuit Court suggested standards for determining when additional work behaviors comprise extra effort: The work behaviors in the higher-paid job must (a) comprise extra effort, (b) require significant time for all of the employees who are classified as being in the higher-paid job, and (c) contribute economic value to the company that is aligned with the job’s pay differential. The first standard is somewhat confusing given its circular logic. However, insight might be gained from cases like Hodgson v. Daisy Mfg. Co. (1971), where the organization argued that male and female press operators did not perform substantially equal jobs because men exercised greater physical effort moving materials and closing large barrels. The 8th Circuit Court determined this did not comprise additional effort under the EPA in part because the effort of the female press push operators was balanced by higher production quotas for the women and the fact that the female workers had to operate machines that ran at high speeds (compromising their physical safety), which involved higher mental effort than the male workers. In order to detect this level of nuance, work requirement descriptors may need to be analyzed qualitatively in order to understand the (non)compensatory effort that is unique to one employee/job in a comparison pairing.

The second and third requirements set by Hodgson v. Brookhaven (1970) are clear and can be investigated by using different job analysis rating scales. The second standard requires that additional work behaviors comprise a significant amount of time (e.g., Schultz v. American Can [1970] found that additional tasks did not require additional effort under the EPA because they only comprised 2–7% of the employee’s time). Manson et al. (Reference Manson, Levine and Brannick2000) demonstrated how to modify a time spent scale to different job contexts by asking fire lieutenants the amount of time they spend working on a particular task (out of 24 hours) and asking police communications technicians how much time a task accounted for out of multiple days (to account for longer work cycles). Although McCormick (Reference McCormick1960) suggested that these types of absolute time spent scales would result in large amounts of error due to employees lacking precision in making such judgement, Manson et al. (Reference Manson, Levine and Brannick2000) reported that absolute scales show reasonable convergent validity with relative time spent scales (e.g., where SMEs are asked how much time they spend on tasks relative to other tasks; 1 = a great deal less, 7 = a great deal more; convergent validities .66–.91). Given the convergent validities and the direct applicability to the standards set through case law, absolute time spent scales may offer value to organizations within this context. Finally, the third standard relates to the financial value of the work behavior. Because many courts would consider this a measure of responsibility, we discuss this standard in further depth next.

Responsibility

A single work behavior can differentiate two jobs if it requires meaningful, additional responsibility. Responsibility refers to the degree to which an employee operates without supervision or supervises others or the extent to which the activities an employee performs affect the organization’s outcomes or business (EEOC Compliance Manual, 2000). Although an employee might not complete a work behavior often, strong consequences for completing it incorrectly would evidence high responsibility in that activity. Ratings of criticality can indicate how much any given work behavior will influence organizational outcomes. Criticality can be assessed for each job analysis descriptor by SME ratings of the consequences of performing the work behavior unsuccessfully (making a mistake) in terms of (a) physical harm to others (e.g., 1 = “no physical harm”; 7 = “physical harm resulting in death”) and (b) financial cost for the organization (e.g., 1 = “no financial loss”; 7 = “financial loss so severe that the organization would cease to exist”; Manson et al., Reference Manson, Levine and Brannick2000, p. 21). Manson et al. also include the negative effect on the employee’s individual performance evaluation (e.g., 1 = “no negative effect on the employee’s performance evaluation”; 7 = “termination of the employee’s employment”) in their assessment of criticality, though this is less relevant to responsibility as the term is used in the legal context.