Professional ethics is a rarely considered subject in industrial-organizational (I-O) psychology, which might imply that it is not of much concern to the field. Yet, if you ask an I-O psychologist about the topic as I have many times, they will likely profess an interest and may even indicate how important ethics are. But for the profession qua profession there are numerous objective and historical indicators of benign neglect. These are some of them:

Among the 57 chapters comprising the four-volume Handbook of Industrial-Organizational Psychology (Dunnette & Hough, Reference Dunnette and Hough1992) there is not one concerned with ethics.

Historical analyses of the field include no mention of the topic (Cascio & Aguinas, Reference Cascio and Aguinis2008; Katzell & Austin, Reference Katzell and Austin1992; Koppes, Reference Koppes2007). Katzell and Austin (Reference Katzell and Austin1992) define the field as consisting of 38 topic areas, and ethical issues are not included.

A review of 29 I-O text books from the 1960s, ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s (Lefkowitz, Reference Lefkowitz2003, Reference Lefkowitz2017) reveals nothing more about the issue of professional ethics than six brief mentions of the existence of the American Psychological Association (2017) Ethics Code.

Integrity and ethics do emerge as competency areas for I-O psychologists in a job analysis, but they are viewed by only 2% and 7% of the survey sample, respectively, as among the most difficult or critical ones (Blakeney et al., Reference Blakeney, Broenen, Dyck, Frank, Glenn, Johnson and Mayo2002).

The annual Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology (SIOP) conference “Call for Proposals” did not include a category for ethical issues among the more than 40 listed until 2003. In recent years it has been included only under the rubric of “Consulting Practices/Ethical Issues”—implying its subsidiary and circumscribed status only in consulting activities, as though there were no ethical issues to be considered in in-house corporate employment, academe, research, publishing, administration, teaching, mentoring, and so on. The past five conferences (2015–2019) have had an average of approximately 12 ethics-related panels, posters, symposia, and so forth among the many hundreds of scheduled presentations and papers, and the number of attendees at those few sessions could readily fit around a modest-size conference table.

In a survey of I-O psychologists’ interests, ethics did not rank better than the middle of a list of several dozen content areas (Schneider & Smith, Reference Schneider and Smith1999; Waclawski & Church, Reference Waclawski and Church2000).

The overriding sentiment among SIOP members has long been against having an enforceable ethical code of our own (Lowman, Reference Lowman1993), and SIOP did not institute an ethics committee of any sort until recently, with the formation of the Committee for the Advancement of Professional Ethics (CAPE), which has an educative function only.

A search of prestigious representative I-O publications—Journal of Applied Psychology, Personnel Psychology, Journal of Business and Psychology, and Industrial-Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice (focal articles only)—for the most recent four calendar years, 2016–2019, revealed 26 (3.8%) of 677 articles that focused on some ethical or moral topic. But none of them concerned professional issues or problems for I-O psychologists.Footnote 1

In more than 100 years of existence there has been no systematic investigation of ethical issues faced by I-O psychologists until the one reported here.

On the other hand, some might take issue with the inference that we have been unconcerned. They can point to indicators that challenge that conclusion—especially in the realm of testing, employee selection, and assessment (e.g., Eyde et al., Reference Eyde, Robertson, Krug, Moreland, Robertson, Shewan, Harrison, Porch, Hammer and Primoff1993; International Taskforce on Assessment Center Guidelines, 2015; Lefkowitz & Lowman, Reference Lefkowitz, Lowman, Farr and Tippins2017). We do have an ethics case book in the field (Lowman et al. Reference Lowman, Lefkowitz, McIntyre and Tippins2006), some texts or other representations of ethical issues in I-O psychology (Lefkowitz, Reference Lefkowitz, Knapp, VandeCreek, Gottlieb and Handelsman2011, Reference Lefkowitz2017; Lowman & Cooper, Reference Lowman and Cooper2018), and recent publications—including one sponsored by SIOP—have focused on socially responsible and humanitarian issues (Carr et al., Reference Carr, MacLachlan and Furnham2012; Carr et al., Reference Carr, Thompson, Reichman, McWha-Herman, Marai, MacLachlan and Baguma2013; McWha-Herman et al., Reference McWha-Herman, Maynard and Berry2016; Olson-Buchanan et al., Reference Olson-Buchanan, Bryan and Thompson2013; Reichman, Reference Reichman2014). However, in addition to some illustrative and inspiring case studies, those treatises largely present normative advice (or encouragement) from a moral perspective—what might be characterized as general “recommended ethical best practices.” For example, one discusses “some specific issues and sources of ethical problems” in employee selection (Lefkowitz & Lowman Reference Lefkowitz, Lowman, Farr and Tippins2017, p. 587); another presents “information … on what are considered standard professional practices in this area” (International Taskforce on Assessment Center Guidelines, 2015, p. 1245). They are educative and prescriptive, some are inspirational, but they are not descriptive of extant ethical problems.

Therefore, regardless of whether or not one believes that I-O psychology has been insufficiently concerned about professional ethics, one thing seems irrefutable: there is a dearth of empirical information about what ethical challenges I-O psychologists actually experience.Footnote 2

Why the lack of study of ethical issues in I-O psychology?

I don’t know. Perhaps the answer is no more complicated than that I-O psychologists don’t find the topic particularly interesting (although ethics has held its own as a scholarly and applied focus for a few thousand years of recorded history). In fairness to ourselves, maybe we are simply representative of a broader socialization process and not remarkable in this regard. I have in mind the observation that across the sciences research ethics is often taught in ways that suggest to students “This is something we unfortunately must require you to do, so let’s get it over with as quickly as we can, and then we can move on to the important things” (Zigmond & Fischer, Reference Zigmond and Fischer2014, p. xviii). Perhaps that generalizes beyond the research domain and is true in I-O psychology as well.

Or maybe unethical behavior is not seen as a significant problem in I-O psychology because we believe ourselves to be rather ethical. That largely has been my subjective impression over the years and is supported by the meager anecdotal data that exist. For example, in responding to an APA ethics survey an I-O psychologist reported “When the context of our work has been explained to executives/managers relating to confidentiality/conflict of interest, etc., no one has ever challenged me or asked me to do something that would compromise the ethical standards of the APA” (Pope & Vetter, Reference Pope and Vetter1992, p. 398, emphasis in the original). However, in the absence of any systematic survey data, and in light of the importance of the topic, it would be a mistake to assume that that person’s experiences are universal, or even typical in the field.

The adverse consequences: What we don’t know and what we should do

What is the incidence and substance of unethical behavior among I-O psychologists or of ethical problems faced by I-O psychologists? How does that compare with other professions or fields of psychology? How does that compare with circumstances 20 years ago? As practicing psychologists, we know very little about the ethical problems we and our colleagues face in corporations, consulting firms, independent practice, academe, government agencies, and wherever else we work. Especially relevant to this study, how might the ethical challenges differ among those work domains? For example, do “in-house” I-O psychologists face more, and more intense, ethical issues than external consultants? How different are the sorts of ethical problems encountered currently by our graduate students or interns from those encountered when we seniors were training? We do not even know factually whether unethical behavior is a notable problem in I-O psychology or which topic areas or work domains might be particularly susceptible or problematic. The sorts of comparative questions posed above are almost never asked—maybe sometimes because the answers are assumed to be self-evident, but often, I believe, because we don’t have the means of addressing them (I will return to this point).

This article has two purposes that are responsive to the issues raised. The first is to present and analyze an extensive data set of self-reported ethical problems from professional I-O psychologists in their own words. To my knowledge this is the first such data in the history of I-O psychology. The second is theoretical and pertains to the study of unethical behavior generally, including professional ethics. It proposes to fill a conceptual deficiency in the way ethical situations are understood. This deficiency may be at least partially responsible for the paucity of research noted above, especially regarding the ability to meaningfully investigate comparative questions. (Perhaps that also contributes to our putative “disinterest.”) It is proposed that a structural point of view be added to existing perspectives by means of a taxonomy of five paradigmatic forms of ethical dilemma. The forms are defined independent of the specific manifest contents of such situations. As explained below, these relatively content-free descriptors provide the means for answering many of the comparative questions posed above. Data from the survey of I-O psychologists are used to provide an empirical test of whether the proposed taxonomy “works.” That is, can it be applied meaningfully and parsimoniously to better understand actual ethical problems?

Existing theoretical frameworks

This article focuses on the core construct of ethical dilemma, and it will be helpful to first place the notion in a broader theoretical context. The study of ethical issues can be segmented into four hierarchical levels of conceptual explanation. The most fundamental level consists of morality’s potential innate evolutionary bases. The inheritance of moral behavior is an active field of study in moral psychology (Doris et al., Reference Doris2010), but it is not without critics (Confer et al., Reference Confer, Easton, Fleischman, Goetz, Lewis, Periloux and Buss2010). Some believe that “it remains unclear whether, and in which sense, morality evolved” (Machery & Mallon, Reference Machery, Mallon and Doris2010, p. 4).

Whether inherited or not, there is rather widespread agreement in psychology and moral philosophy regarding what can be construed as a second theoretical level—the underlying value dimensions constituting what has been called the “domain of moral action” (DMA; Lefkowitz, Reference Lefkowitz2017, p. 111), including ethical behavior, thoughts and feelings about ethical behavior, and their antecedents and consequences. This includes normative ethical theories (deontological, consequentialist, or virtue based) and the moral emotions (Arrington, Reference Arrington1998; Prinz & Nicholls, Reference Prinz, Nichols and Doris2010). The three broad value dimensions are justice (concerned with criteria of fairness, impartiality, and universalizability of treatment); welfare (with criteria of beneficence, altruism, and harm avoidance; cf. Boyd, Reference Boyd and Puka1994; Frankena, Reference Frankena1973); and character, or virtue (MacIntyre, Reference MacIntyre2007).

Those metadimensions (justice, welfare, virtue) have been refined into various sets of more particular, yet still relatively abstract, ethical principles, like those contained in the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (American Psychological Association, 2017) and the Canadian Code of Ethics for Psychologists (Canadian Psychological Association, 2017). Principles such as beneficence; fairness and justice; fidelity; nonmaleficence; personal and professional integrity; respect for the autonomy, rights, and dignity of others; and responsibility to society constitute the third conceptual level. Although these are more precise than the metavalue dimensions that define the DMA, they are nevertheless still “General Principles” and “aspirational goals” representing the “highest ideals of psychology” (American Psychological Association, 2017, p. 2, emphases added).

The requisite role demands, job knowledge, skills, abilities, specific work functions, and context obviously vary greatly among different professions. Accordingly, the fourth conceptual level, consisting of the overt or manifest content of ethically challenging situations encountered within each field also differ. So each field produces its own largely idiosyncratic treatment of ethical considerations: For example, in medicine (Beauchamp & Childress, Reference Beauchamp and Childress1994; Cohen-Almagor, Reference Cohen-Almagor2000), business management (Schminke, Reference Schminke2010; Treviño & Nelson, Reference Treviño and Nelson2004), psychotherapy (Tjeltveit, Reference Tjeltveit1999), policing (Kleinig, Reference Kleinig1996; Skogan & Frydell, Reference Skogan and Frydl2004), statistics (Panter & Sterba, Reference Panter and Sterba2011), and anthropology (Cantwell et al., Reference Cantwell, Friedlander and Tramm2000)—to note just a few. Even within the single discipline of psychology, the variety of subfields and professional circumstances necessitates more than three dozen independent chapters (Knapp et al., Reference Knapp, VandeCreek, Gottlieb and Handelsman2012).

Consequently, both scholarship and the benefits of applied experience remain largely isolated within the metaphorical “silos” of each field. Each individual profession (and other entities such as public and private sector organizations) generates its own compilation of domain-specific “ethical problems,” “ethical issues,” “ethically troubling incidents,” “ethical situations,” or “ethical dilemmas” at the manifest level. These are often accompanied by the promulgation of formal ethics codes within each field (e.g., American Psychological Association, 2017; Canadian Psychological Association, 2017), by illustrative case books (Lowman et al., Reference Lowman, Lefkowitz, McIntyre and Tippins2006), and by supplementary explications of the codes (Bersoff, Reference Bersoff2008).

To summarize, the most commonly used conceptual frameworks for understanding moral behavior are innate evolutionary potentials, metavalue dimensions, normative ethical principles, and the overt ethical problems or dilemmas that represent their particular distinctive behavioral expression. The “conceptual deficiency” referred to earlier is the gap between the largely covert, abstract, and sometimes ambiguous nature of the first three conceptual levels and the fourth, which consists of their idiosyncratic overt manifestations characterized as ethical dilemmas in each of the domains of human activity.

This paper suggests that the gap can be bridged meaningfully by inserting an additional conceptual level between the existing third and fourth levels, consisting of the form or structure of ethical dilemmas. Those terms are defined, here, as in common usage. Form refers to “the visible shape or configuration of something,” or the “style, design, and arrangement in an artistic work as distinct from its content” (Oxford English Dictionary, n.d.-a). Structure refers to “the arrangement of and relations between the parts or elements of something complex” or “the quality of being organized” (Oxford English Dictionary, n.d.-b). Thus, as applied to this area, the form or structure of an ethical dilemma would consist of the social, psychological, and contextual elements comprising it and the relationship(s) among them. Those parts or elements are commonly: motives (self-interest, ambition, empathy); cognitions (anticipation of actions by others, expected consequences); emotions (shame, pride); values (nonmaleficence, justice); duties (familial or professional fiduciary responsibilities); or stressors (physical or emotional threat, cognitive overload). They often exist in combination: for example, a justifiable set of duties may imply certain motives that also reflect particular values and cognitions. The critical point, elaborated below, is that these are generic structural features of ethical dilemmas not specific to any field, profession, organization, institution, or other sphere of human activity. Thus they can be used to conduct meaningful research involving the aggregation and/or comparison of findings across such domains.

Ethical dilemmas

Definition and distinguishing attributes of ethical dilemmas

The notion of ethical dilemma has been a core construct in moral philosophy at least since Socrates’s consideration of “justice” in Book I of Plato’s Republic (McConnell, Reference McConnell2018) through Sartre’s (Reference Sartre1957) description of a young Frenchman during World War II, torn between leaving to join the Free French resistance against the Nazis or staying home to care for his elderly mother.

McConnell goes on to observe that “debates about moral dilemmas have been extensive during the last six decades. These debates go to the heart of moral theory” (§10). For example, some “opponents” of moral dilemmas believe that “an adequate moral theory should not allow for the possibility of genuine moral dilemmas” (§3) because the ostensibly conflicting actions can always be shown to be hierarchically ordered, with one prevailing over the other—even if that is not intuitively evident to the actor. Conversely, “proponents” call attention to symmetrical cases in which the same moral precept leads to conflicting obligations or to situations in which whatever choice is made one can anticipate experiencing remorse and guilt or regret.Footnote 3

Other issues concern the differences between certain types of dilemmas: (a) epistemic conflicts (the actor does not know which of the conflicting precepts takes precedence) and ontological conflicts (neither precept can be overridden by the other), (b) self-imposed moral dilemmas (such as by having made conflicting promises) versus dilemmas imposed on a person by the world (e.g., role-related obligations), or (c) obligation dilemmas (more than one feasible action is morally obligatory) versus prohibition dilemmas (all feasible actions are morally forbidden). These considerations are offered briefly to reflect the range of scholarship to which the focal construct has been subjected; but they extend beyond our requirements here.

The question “What is an ethical dilemma? can be disaggregated into “What makes a problem ‘ethical’ in nature?” and “what makes it a ‘dilemma?’” With respect to the first, Wittmer (Reference Wittmer and Cooper2001) concluded that “an ethical situation is taken to be essentially one in which ethical dimensions are relevant and deserve consideration in making some choice that will have significant impact on others” (p. 483). That is, there are three elements: a choice situation that invokes ethical/moral principles and which has substantial consequences for some people.

With regard to the second question, a dilemma is defined as “a usually undesirable or unpleasant choice” or “a situation involving such a choice”; “broadly: predicament” (Merriam-Webster Unabridged Dictionary, n.d.). The dictionary entry goes on to note that “what is distressing or painful about a dilemma is having to make a choice one does not want to make.” Although the Merriam-Webster dictionary does not contain an entry for “ethical dilemma,” the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy notes that the crucial feature of a moral dilemma as generally construed in philosophy is conflict. According to McConnell (Reference McConnell2018, §2), “The agent is required to do each of two (or more) actions; the agent can do each of the actions, but the agent cannot do both (or all) of the actions. The agent thus seems condemned to moral failure; no matter what she does, she will do something wrong (or fail to do something that she ought to do).”

In defining a construct such as ethical dilemma and the misbehavior for which it may be responsible, it is necessary to distinguish it from two very similar kinds of misbehavior with which it is often conflated. These are so similar that they may be construed as “boundary conditions” of the construct of ethical dilemma. They are incivility or rudeness and corruption, and their distinctions from ethical dilemmas may not be easily made in practice.

Differentiation from incivility

As noted by Prinz (Reference Prinz and Sinnott-Armstrong2008) and McConnell (Reference McConnell2018), the common understanding of ethical dilemmas in philosophy concerns potential conflicts among moral norms. Those moral norms are distinct from social (nonmoral) norms of conventional behavior (Prinz & Nichols, Reference Prinz, Nichols and Doris2010; cf. Legros & Cislaghi, Reference Legros and Cislaghi2020, for a review of the social-norms literature). Scholars “have often had difficulty … differentiating norm-violating behavior that can be clearly thought of as unethical or immoral, from behavior that fails to conform with social expectations and so is unconventional, rude, and perhaps even antisocial and hostile, but that does not sink to the level of being immoral or egregiously harmful” (Lefkowitz, Reference Lefkowitz, Cooper and Burke2009, p. 61). This has sometimes been referred to as “nuisance behavior” (Lewis, Reference Lewis, Thomas and Hersen2004); in this paper it is characterized as rudeness or incivility. The use, here, is commensurate with how it is defined by scholars in the area to refer to “interpersonal mistreatment” and “low intensity deviant behavior with ambiguous attempt to harm the target, in violation of … norms for mutual respect” (Lim & Cortina, Reference Lim and Cortina2005, p. 483) or as “rude, condescending, and ostracizing acts that violate … norms of respect” (Cortina et al., Reference Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Magley and Nelson2017, p. 299). Such behavior differs from aggression in lacking “unambiguous intentions and expectations to harm the target” (Lim & Cortina, Reference Lim and Cortina2005, p. 483). As an illustration, imagine that you are alone in an elevator, late for an appointment, impatiently waiting for the doors to close; just as the doors start to shut someone comes running down the hallway breathlessly shouting “hold the elevator, please, hold the door!” You might very well experience a dilemma whether to be rude or late. But most would not consider it a moral or ethical dilemma.

Differentiation from corruption

Implicit in the discussion of ethical dilemmas is the presumption that the person experiencing such a predicament is motivated, to some nontrivial degree, by justice/caring/virtuous motives to avoid causing harm and/or to abide by ethical norms and principles—in short, to do the right thing. (Hence the predicament or dilemma.) So in that sense, unethical behavior represents an ethical “failure.” One might succumb due to the greater salience of egoistic-asocial motives, external pressures, being prevented by circumstances from acting ethically, and/or other situational impediments. This view is in keeping with recent motivational perspectives such as Nisan’s (Reference Nisan and Wren1990, Reference Nisan, Kurtines and Gewirtz1991) model of moral balance or a licensing effect for ethical transgressions (Mullen & Monin, Reference Mullen and Monin2016), and the theory of self-concept maintenance (Mazar et al., Reference Mazar, Amir and Ariely2008), which is based on “the premise that most people typically value honesty, believe themselves to be moral and are motivated to maintain that self-concept” (Lefkowitz, Reference Lefkowitz2017, p. 162; also cf. Abeler et al., Reference Abeler, Nosenzo and Raymond2019).

Therefore, this conceptualization distinguishes such ethical failings from so-called intentional unethical behavior, which is arguably better characterized as corruption. Although there has been considerable disagreement regarding the definition of corruption (cf. Ashforth et al., Reference Ashforth, Gioia, Robinson and Treviño2008; Dion, Reference Dion2010; Lefkowitz, Reference Lefkowitz, Cooper and Burke2009; Quinones, Reference Quinones2000), the misbehaviors referenced are invariably intentional and often planful. The distinction is illustrated by the difference between the likely ethical dilemma experienced by many midlevel engineers and technicians at VW who were directed to carry out the diesel exhaust subterfuge in comparison with the corruption of the senior people who designed, implemented, and maintained the worldwide strategy for some time. Corrupt actions may vary in degree—for example, from taking home from work (i.e., stealing) a small amount of office supplies to the actions of a Bernard Madoff who swindled his victims mercilessly.

A proposed taxonomy of ethical dilemmas

To illustrate the conceptual deficiency or “gap” referred to earlier, consider that at the theoretical level of normative ethical principles, the principle of “fairness and justice” implies virtually nothing substantive about any of the enormous number of situations or ethical dilemma(s) in which the principle may be invoked. It would be exceedingly useful if there were a meaningful and parsimonious group of generic situations that (a) accurately reflect the ethical principles; but (b) are more precisely defined than those abstract, sometimes ambiguous principles; yet are also (c) not idiosyncratically domain specific, as the manifest problems or dilemmas generally are. Such a scheme could provide a basis for meaningful analyses of ethical experiences across domains (of professions, organizations, demographic groups, age cohorts, etc.), even though the overt features of those experiences may have nothing in common, and/or over time—during which technological advances, social policies, and other changes give rise to new manifest ethical issues (cf. Lefkowitz, Reference Lefkowitz2006). The paradigmatic forms of ethical dilemmas presented here represent just such a scheme.

Origins

One of the most influential psychological theories of moral development in the late 20th century was Martin Hoffman’s (Reference Hoffman, Bornstein and Lamb1988, Reference Hoffman2000) empathy-based information-processing model of how children internalize society’s mores. Among the major components of the model are three ideal types of moral dilemma from which a child may, subject to appropriate rearing practices, develop what later scholarship refers to as moral emotions (Prinz & Nichols, Reference Prinz, Nichols and Doris2010). They are: (a) being an innocent bystander to someone else’s pain or distress; (b) being the cause, or potential cause, of harm to another; and (c) having to reconcile competing obligations to two or more persons.

Lefkowitz (Reference Lefkowitz2003, p. 129) indicated that these three general types of moral problems “seem sufficiently inclusive to provide the basis for expansion into a useful taxonomy of ethical challenges (including situations that may entail combinations of two or more of them).” He also added another paradigmatic situation not enumerated by Hoffman (who after all, was studying young children): (d) facing conflicting and relatively equally important personal values so that expressing one entails denying the other(s) expression. A fifth was subsequently included: (e) coercion—being pressured to violate ethical standards (Lefkowitz, Reference Lefkowitz2006, Reference Lefkowitz, Knapp, VandeCreek, Gottlieb and Handelsman2011).

Following Hoffman’s characterization of his three as “ideal types,” it is proposed that these represent five generic or paradigmatic structural forms of ethical dilemma; that is, they pertain to most, perhaps all, domains of potential ethical difficulties because they are essentially “content-free.”Footnote 4 They do not depend on the specifics of the particular ethical difficulty—other than the form(s) it takes, as specified below.

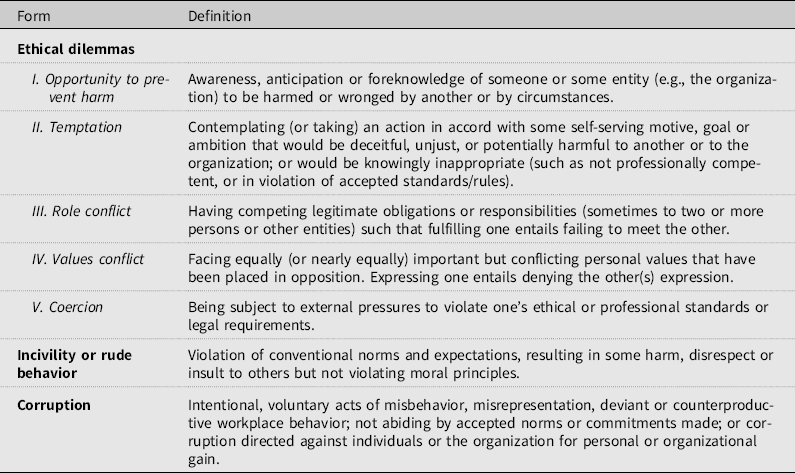

Table 1 presents definitions of the five paradigms of ethical dilemma as well as the external boundary conditions of rudeness or incivility, and corruption. The five forms of ethical dilemma are not mutually exclusive. The complicated nature of human interaction in complex social settings may be reflected in multidimensional dilemmas that involve more than one form. For example, the coercion to which the VW technicians were subjected probably also entailed values conflict and/or role conflict. This overlap does not imply a theoretical weakness or invalidation of the proposed categorization scheme.Footnote 5

Table 1. Five Structural Forms of Ethical Dilemma and Other Misbehavior

Note. Definitions include minor editing and elaboration of the a priori definitions, following initial coding of a random sample of replies from the current study.

Taxonomic evidentiary criteria

If this scheme is to be accepted as a useful addition to the understanding of ethical issues, what needs to be shown empirically is that (a) the five forms comprising the taxon of ethical dilemmas are exhaustive—that is, that all five are found in a sufficiently large sample of dilemmas; none are superfluous;Footnote 6 (b) the taxon is comprehensive—that is, that virtually all dilemmas may be represented by at least one of the forms; in other words, there are not a lot of “unclassifiable” dilemmas; and (c) dilemmas are distinguishable from manifestations of other constructs like superficially similar instances of incivility/rudeness and corruption. In other words, the essential question is “Does the taxonomy work?” What is required in order to attempt those three showings is a substantial number of actual ethical dilemmas. In addition, because in this investigation the dilemmas are elicited as personal narratives so that the forms are assessed subjectively, the coding of qualitative descriptions of ethical situations must be able to be done reliably.

Fortunately, such a dataset is available. A survey had been conducted in 2009 to obtain real-world narratives of ethical situations experienced by a large, perhaps representative, sample of I-O psychologists and to document examples of ethical issues from various areas of I-O practice. To my knowledge, no such empirical data existed at the time.Footnote 7 That the source of the dilemmas is from I-O psychology is likely of considerable relevance to readers of this journal, but it is of no distinctive value with respect to the theoretical research question regarding the forms of ethical dilemmas and their usefulness. Any sufficiently large set of ethical dilemmas from another population—or better still, a heterogeneous combination of populations—could serve as a means of investigating the evidentiary criteria.

Method

Participants and procedure

Following university IRB approval, an e-mail inviting anonymous participation in an online survey was sent to U.S.-based active members and fellows of SIOP (American Psychological Association Division 14), excluding retirees, international and associate members, and student affiliates, in the fall of 2009; n = 2,524.Footnote 8 They were asked to link to the survey and respond to the demographic items even if they had no ethical situation(s) to report, in hopes of maximizing the representativeness of the sample. Replies were received from 661 (26.2% response rate.) By way of comparison, an earlier mailed ethics survey of APA members (Pope & Vetter, Reference Pope and Vetter1992) with stamped return envelopes yielded a more favorable return rate of 51%. However, unlike this survey, that one purposefully omitted demographic items and respondents were tasked with describing incidents only “in a few words” (p. 398). Even those authors report that return rates “of 15% [have] tended to be the range of all surveys that request actual incidents regarding problems of ethics” (p. 398). Moreover, a contemporary SIOP employment survey had a comparable response rate of 29.1% (Khanna & Medsker, Reference Khanna and Medsker2010), and a more recent one yielded 24.0% (Poteet et al., Reference Poteet, Parker, Herman, DuVernet and Conley2017).

Although 248 (37.5%) of the respondents indicated that they had recently (i.e., “within the past few years,” as specified) experienced an ethical situation, only 228 (34.5%) described one or more such, for a total of 292 incidents. That is, almost 10% of the SIOP population reported experiencing or observing at least one ethical situation, and 9% offered descriptions.

The responding sample is described in Table 2. Of the 656 respondents who indicated their sex, 56.4% are men and 43.6% women. An appropriate comparison with the SIOP population from 2009 is not possible, as SIOP did not require reporting of sex and fewer than 60% of the members and Fellows voluntarily reported it (L. Nader, personal communication, June 11, 2018). But among those who did report it, the distribution is virtually the same as for this sample: 55.9% men and 44.1% women. Among the 657 who reported their highest degree, 99.5% held a doctorate (0.5% held a master’s), which is comparable to 2,510 (99.4%) for the population at the time (L. Nader, personal communication, June 11, 2018). Seventy-nine percent held a doctorate in I-O psychology, and the median number of years since degree is between 11 and 20. Of all respondents 51 (7.7%) are Fellows; that is in comparison with 279 (11.05%) of the SIOP population at the time.

Table 2. Demographic Description of the Survey Sample

Note. Of the total, 228 reported one or more narrative descriptions of an ethical situation.

a Total respondents.

The survey questionnaire

Respondents were first asked to reply to five closed-ended demographic items, indicating their sex, highest academic degree, its field, number of years since degree, and SIOP membership status. Those having had no recent experience with an ethical situation were instructed to submit the survey at that point. Otherwise, they responded to four questions concerning up to two situations: Question 1: a five-alternative item describing one’s role in the situation (e.g., “I was the person actually faced with the ethical issue”; “I was not directly involved, but was able to observe or otherwise be aware of the situation”); Question 2: five options indicating in what capacity they were primarily functioning at the time (practitioner, academic, researcher, administrator/mgr., other); Question 3: an open-ended description of the situation; and Question 4: an open-ended explanation of why they consider the situation “ethical” in nature.Footnote 9

Content analysis of descriptions of the ethical situations

Content analysis has been characterized as a “flexible methodology [that] … employs a wide range of analytic techniques” (White & Marsh, Reference White and Marsh2006, p. 22) and has been used in many fields of research, including organizational scholarship (Pratt, Reference Pratt2009). This study deductively employs a priori coding schemes and modest (ordinal) quantitative analyses of the qualitative responses. This entails “establish[ing] a set of categories and then count[ing] the number of instances that fall into each category. The crucial requirement is that the categories are sufficiently precise to enable different coders to arrive at the same results when the same body of material … is examined” (Silverman, Reference Silverman2015, p. 116).

Respondents’ replies to Question 3 were analyzed: “Please describe the situation in some detail. What led up to the situation? What transpired: For example, what resources were brought to bear? How did it conclude: For example, was the issue resolved satisfactorily?” Replies to Question 4 (“What about the situation, in particular, leads you to define it as ethical in nature?”) elicited primarily elaborations of replies to Question 3, and so were incorporated in coding Question 3; they were not considered/coded separately. The coding scheme assessed four attributes of each narrative, as follows.

-

1. Paradigmatic form of dilemma or other misbehavior

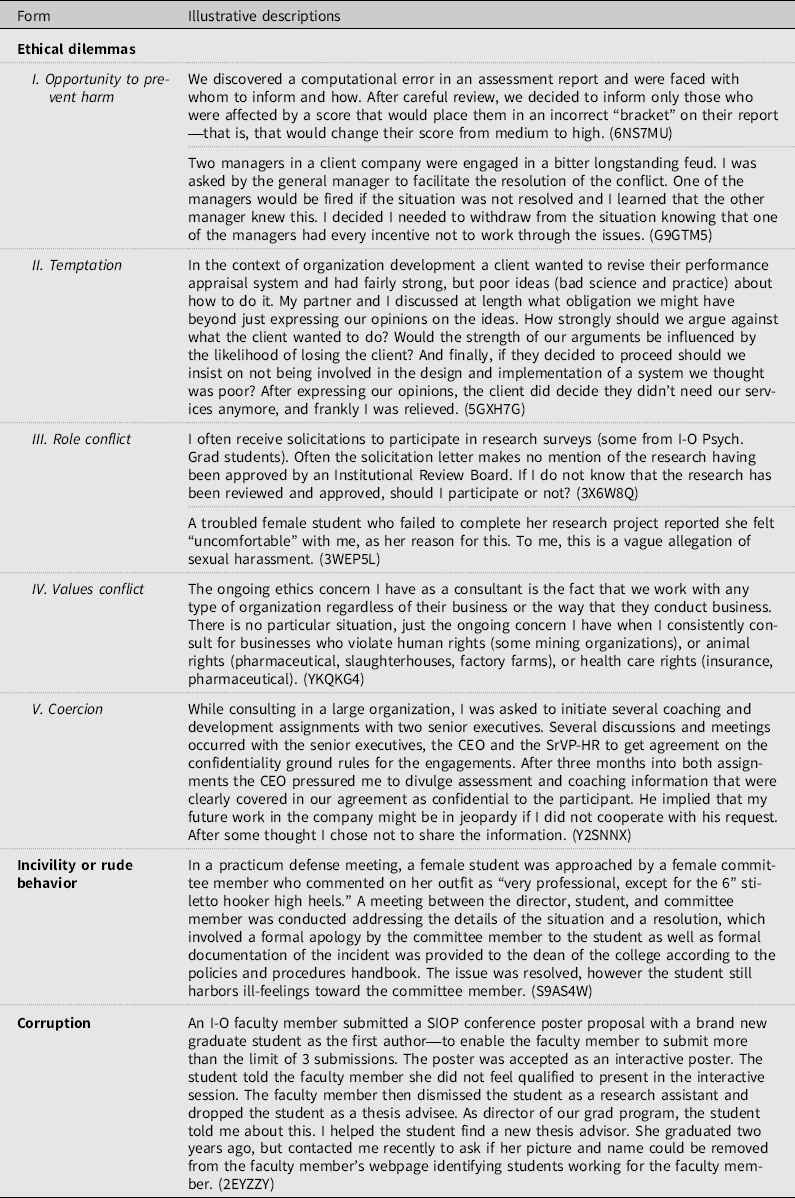

The seven categories of nonnormative behavior discussed earlier and presented in Table 1 comprise the major coding categories for this analysis. Given that the five paradigmatic forms of ethical dilemma are not mutually exclusive, up to two forms were coded for each reply, if warranted. Table 3 presents a few illustrative verbatim replies to Question 3 for each of the categories.

Table 3. Sample Responses Representing the Forms of Dilemma or Misbehavior

Note. Some of the narratives were scored for two categories (see text). Alphanumeric strings are unique case identifiers.

A few replies communicated an unambiguous understanding of an ethical situation in which a proper course of action was clear to the respondent, with no substantial impediments, and the intention to do the right thing was expressed, without hesitation, doubt, or ambivalence. In other words, phenomenologically there was no “dilemma” experienced or corruption contemplated. In addition, a few replies were merely general descriptions of inappropriate, unethical or unlawful situations that putatively existed, without any personal involvement noted. In other words, again, no dilemma was reported. For both of these types of responses an eighth coding category, labeled “Ethical Clarity,” was added to the seven shown in Table 1.

-

2. Work domains in which ethical situations occur

In contrast to the generic structure of ethical dilemmas represented by the five paradigms, and the general categories of incivility and corruption, it is obviously of some interest to learn in which particular areas of the I-O psychology field ethical problems might be most prevalent. A coding scheme of 32 areas (plus “other, not specified, or not interpretable”) was used (cf., Results, Table 4). The categories were derived from available sources: I-O psychology text books, education and training guidelines in I-O Psychology (Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1999a, 1999b), typical organizational human resource systems (Buckley, et al., Reference Buckley, Beu, Frink, Howard, Berkson, Mobbs and Ferris2001), and the topic categories for submission of presentations at SIOP’s annual conferences. Provision was made for coding up to two domains per situation, if warranted.

Table 4. Overall Findings

Note. Missing responses not included in calculating category percentages.

aMissing data not counted. bPercentage of distribution for the five dilemmas only. cSituations from academe not considered.

Most (n = 26) of the coding categories refer to practice areas that might exist in any organization; three refer specifically to aspects of work in academe (Nos. 22–24), and three refer to professional consulting issues concerning clients, colleagues, or competitors (Nos. 29–31). For any reply that was coded 29, 30, or 31, an attempt was made to also code a practice area, if possible. No provision was made for noting public sector (government) employment, and very few such instances were apparent from the narratives.

3. Ethical issues from management/human resource administration

Much of the scholarship in administrative, managerial, and business ethics is theoretical and/or philosophical in nature (e.g., Cooper, Reference Cooper2001; Schminke, Reference Schminke2010) or presents idiosyncratic, elaborated case studies (e.g., Ferrell et al., Reference Ferrell, Fraedrich and Ferrell2002; Petrick & Quinn, Reference Petrick and Quinn1997)—which are not particularly helpful as a source (or comparison) for empirical experiences. However, there have been a number of studies that are potentially useful. Gaumnitz and Lere (Reference Gaumnitz and Lere2002) identified common ethical issues from the contents of 15 codes of ethics from professional business organizations; Wiley (Reference Wiley2000) performed a similar analysis with respect to professional codes of ethics in human resources (HR); and Wooten (Reference Wooten2001) surveyed the ethical codes of five professional associations in relation to five general ethical dilemmas in eight areas of human resource management (HRM). Treviño and Nelson (Reference Treviño and Nelson2004) also present some common ethical problems for managers. Scoring the reported situations with 13 coding categories based on these insights facilitates direct comparisons with the world of business/HRM (cf., Results, Table 4). Situations from academe are not commensurable with the business domain, so narratives solely from the academic domain (n = 91) were not coded on this attribute.

Although the HRM coding categories seemed conceptually clear, they proved to be problematic in use because some of them are very broad, encompassing a wide variation in manifest content; some of the categories overlap or seem redundant in practice; and some are highly interrelated.

-

4. Resolution of the situation

The original coding scheme for describing the favorableness of each ethical situation’s resolution used a five-point scale in response to the prompt embedded in Question 3: “Was the issue resolved satisfactorily?” Initial trials at coding (see below) revealed that it was extremely difficult to differentiate a satisfactory from a partially or mostly satisfactory resolution and an unsatisfactory from a largely unsatisfactory resolution. Consequently, the coding was condensed to a three-point scale: 1 = “Positive. Resolved satisfactorily or mostly satisfactorily,” 2 = “Mixed or uncertain resolution,” 3 = “Negative. Not resolved satisfactorily (or at all).” In addition, 9 = “Could not code (extent of resolution not mentioned or issue not yet resolved).”

Reliability of content coding

Although most of the coding categories are close to the level of the manifest content of the reported narratives (thus requiring little inference), as indicated above by Silverman (Reference Silverman2015) it should be demonstrated that the categories are sufficiently clear to yield consistent coding. (The four coding schemes were comprised initially of a total of 60 scoring possibilities; that was reduced to 58 with the condensation of the scale for coding the resolution of the situation.)

In accord with traditional frame-of-reference training (Bernardin & Buckley, Reference Bernardin and Buckley1981), the author and an experienced I-O psychologist practitioner with an interest in ethical issues met to discuss the rating categories. For initial training, seven respondents were chosen at random and their narratives were coded independently on up to six variables by both coders (up to two forms of ethical misbehavior, up to two practice areas, the Mgt/HRA issue, and the resolution). The coders agreed on 27 of 32 ratings (84.4% consistency). The coding scheme was again discussed in general and the disagreements were reevaluated to the point of agreement. Also, at this time, the coding scale for resolution was condensed from five to three.

An additional 10 respondents were picked at random requiring 40 judgments that were made independently. The two coders agreed on 37 of the 40 (92.5%); moreover, two of the three discrepancies were from the problematic Mgt/HRA issues. Thus the level of agreement for the two critical dimensions of ethical dilemma or misbehavior (seven categories) and practice area/work setting (32 categories) was 95% (19 of 20). Although it has long been known that percentage of agreement statistics can be inflated by chance agreement (Cohen, Reference Cohen1960; Goodman & Kruskal, Reference Goodman and Kruskal1954; Scott, Reference Scott1955) that is not an issue with these data. The upper limit of Cohen’s (Reference Cohen1960) coefficient of agreement is 1.00, “occurring when (and only when) there is perfect agreement between the judges” (p. 41). That is in fact approached in this instance. Therefore, the remaining replies were scored individually by the author.Footnote 10

Results

Representativeness

An issue regarding representativeness of the sample might be raised. Is the study sample representative of the SIOP membership? However, no such claim of representativeness is offered because it is not relevant to the theoretical purpose of the study—assessing the utility of the taxonomy—nor to the goal of obtaining a first-ever sample of ethical incidents from this population.Footnote 11

On the other hand, a legitimate concern might be expressed concerning the representativeness of the 292 reported ethical situations, not the 228 respondents--i.e., whether the sample of dilemmas provides an adequate basis for evaluating the taxonomy. (For example, if one or more of the forms of dilemma are not represented among the incidents, it might reflect an inadequate sampling of situations rather than a problem with the specification of forms.) Unfortunately, that is an unanswerable question, as the population of manifest ethical dilemmas is unknown, unspecifiable, and probably enormous. But notwithstanding its lack of theoretical relevance, sample representativeness arguably might be taken as an imperfect marker or indicator of situation representativeness. (Although I would not press the point strongly.) That is why, following an earlier precedent (Pope & Vetter, Reference Pope and Vetter1992), respondents were asked to link to the survey and answer the demographic items even if they had no ethical situation to report.

In any event, there is nothing to suggest that the respondents are not typical of the SIOP membership at the time, although somewhat fewer of them were fellows. Their level of education was identical; the field of degree (91% in psychology and 79% in I-O psychology) seems representative, and as noted earlier the response rate to the survey was highly similar to those of other voluntary SIOP surveys—both at the time and more recently. Moreover, the male/female ratio (.56/.44) was the same as for those who voluntarily reported that information to SIOP.

Findings regarding the experience of ethical dilemmas

Table 4 summarizes the data and yields the following observations:

-

1. The narratives largely reflect these I-O psychologists’ first-hand experiences with ethical situations. In 83.9% of the situations, the respondent was directly involved in some way, and in almost half (47.9%), the respondent was the person actually faced with the ethical issue.

-

2. Not unexpectedly, more than half of the situations (55.8%) occurred while in the role of practitioner. However, there are no baseline data of which I am aware that would show whether ethical situations are disproportionately more common in professional practice than in other work roles.

-

3. Coercion was by far the most frequently represented among the five forms of ethical dilemma (37.3%), often in conjunction with another. It represented 26.5% of all seven categories of misbehavior. Intentionally corrupt acts—not herein considered “dilemmas”—were equally frequent (26.5%), in part because they often occur in combination with coercion. (Typically, intentionally corrupt actions by one person causing a coercive dilemma for some other[s].)

-

4. Very few incidents were coded as “incivility or rudeness.” Because respondents had been prompted to report ethical situations, this finding suggests that they effectively differentiate unethical behavior from rudeness. (Or perhaps ethical dilemmas merely are more salient and memorable than instances of incivility.)

-

5. Ethical situations apparently may be encountered in a wide variety of work areas: 23 of the 33 work domains (including “other”) were involved. However, just four domains (not counting “other”) were involved in 42.3% of the situations. (Note that some situations involve more than one work domain.)

-

6. Eight work domains most fraught with ethical challenges were, in rank order, academic research/publication, individual assessment, client issues in consulting, academic supervising of students, rank-and-file staffing, academic teaching and administration, attitude/climate surveys, and managerial development/coaching—accounting for 68.7% of the total.

-

7. The most fraught areas from a managerial/HR perspective were maintaining confidentiality, honesty and integrity, and obligation to the profession or colleagues. This is commensurate with the HR literature noted earlier.

-

8. It is unsettling to find that fewer than one third (30.6%) of the situations were apparently resolved positively—about the same as those resolved negatively (31.7%). A slightly larger proportion was of mixed/uncertain resolution or not yet resolved (37.7%).

Individual differences in the experience of ethical dilemmas

These analyses are exploratory. No research questions were posed, and the author is not aware of any data suggesting significant differences between demographic subgroups of professionals in their experience or observation of ethical dilemmas. In any event, with so many scoring categories the within-cell frequencies of many cross-tabulations are too small for meaningful statistical analyses. Where analyses were feasible they generally indicated uniformity (results not shown). That is, there were no significant differences between male and female respondents in the role they played in the ethical situations reported, the capacity in which they were functioning at the time, the form of dilemma or misbehavior noted, nor favorability of resolution. However, men were more likely than were women to have been working as administrator/manager: 13.4% vs. 5.4%. There also were no significant differences as a function of seniority (years since highest degree) or SIOP membership status (member vs. fellow). However, those whose degree is in I-O psychology (n = 262) were more likely to report situations involving some coercion than were all other respondents combined (n = 70, χ2 = 19.37, df = 8, p = .013). An interpretation of that finding remains to be elucidated.

Summary and conclusions

Based on the three evidentiary test criteria posed the taxonomy appears to work. It was exhaustive in that all five forms were represented in the sample of 292 ethical situations; none of the structural forms was empirically moot. Second, the taxonomy proved comprehensive in that the forms (along with the categories of incivility and corruption) were able to account for virtually all of the manifest situations presented. Only 10 (3.0%) of the situations reported were “uninterpretable” with respect to their form, and that reflected ambiguous or inadequate descriptions, not necessarily a lack of comprehensiveness of the taxonomy. Third, ethical dilemmas appear to be distinguishable from rudeness/incivility. Only eight (2.6%) of the situations offered by respondents in response to a request to describe “an ethical situation or situations” were deemed to be mere rudeness. “Intentional unethical behavior” or corruption, proved to be a salient and distinctive form of situation—albeit not meeting the definition of ethical dilemma followed here. However, corrupt acts by one person sometimes gave rise to a dilemma for others.

Because one purpose of the study was to obtain real-life narratives, that response mode led to a requisite assessment of coding reliability. Subjective coding of a sample of respondent narratives using the seven categories was demonstrably reliable. However, in future surveys respondents can be asked to characterize the structure of their ethical dilemmas directly, using closed-ended formats, thus obviating the need for subjective coding.Footnote 12 The construct validity and theoretical usefulness of the structural forms of dilemmas ought to be independent of any particular response format.

Ethical issues in I-O psychology

Based on a response rate of 26.2%, and knowing that this was not a random sample of SIOP members, generalizing from these data regarding the overall incidence of ethical situations experienced by I-O psychologists is not warranted (although the response rate was within the expected range). If one assumes that none of those who failed to respond to the survey solicitation had experienced or observed an ethical situation “within the past few years” (thus were not sufficiently motivated to reply), those who did describe such represent almost 10% of the operational population. Is it truly the case that more than 90% of professional I-O psychologists had not encountered an ethical situation for a few years? If so, is that result to be expected? How does it compare with other fields? Is it the same as in the past? Should it be a source of comfort or alarm? Currently, there are no bases on which to make such normative/comparative judgments.

Some of the survey results seem surprising—both positively and disappointingly. One can be pleased to observe the low incidence (in 2009) of ethics reports regarding sexual harassment, legal employment issues, unfair discrimination in personnel actions, diversity and affirmative action, and organization downsizing.

On a cautionary note, we can hardly be sanguine that the most frequent reported form of ethical dilemma involves coercive behavior (37.3%; 26.5% of all nonnormative behavior). That is exacerbated by intentional corrupt behavior, also in 26.5% of the situations. From an HRA perspective, approximately two thirds of the situations involved challenges to maintaining confidentiality and honesty/integrity or fulfilling obligations to others or to professional standards. These were manifested mostly in dealing with pressures from consulting clients or senior managers, often in the context of individual assessment activities or surveys. It is also noteworthy that academe accounted for approximately 30% of the work domains coded—stemming from research and publication activities; supervising, advising, and mentoring students; and teaching and administrative duties.

Also it is disheartening to learn that less than one third of the situations were resolved satisfactorily or mostly satisfactorily.

The reader is invited to mull over what these findings might suggest, if anything, about the inferred issue debated at the outset, whether the field of I-O psychology is insufficiently concerned about professional ethics.

Theoretical contributions

This article noted that the understanding of unethical behavior can be conceptualized by levels of theoretical analysis and could be enhanced by incorporating an additional level, the structural form of an ethical dilemma. The resulting five hierarchical levels would now include: innate evolutionary bases; the metavalue dimensions of the DMA (justice, welfare, virtue); the derivative general ethical principles (beneficence, fidelity, etc.); five paradigmatic structural forms of dilemma; and the manifest ethical situations. Moreover, this study expanded the definition of ethical dilemmas typically used in philosophy—generally limited to the consideration of conflicts (McConnell, Reference McConnell2018)—to five paradigmatic forms and demonstrated that they can be distinguished from the similar constructs of incivility and corruption. Those five forms were sufficiently comprehensive—that is, no additional ones were needed to accommodate all of the reported situations.

The analysis incorporated a definition of unethical behavior (violation of moral norms) that differentiates it from incivility or rudeness (violation of social norms of conventional behavior). It defines ethical dilemmas as choice predicaments in which the protagonist has some nontrivial motivation to “do the right thing,” thus differentiating such dilemmas from intentional corruption. Therefore, unethical behavior, as an adverse outcome to a dilemma, can be thought of as an ethical “failure.” One might fail to surmount an ethical challenge because of (a) individual-difference attributes such as inadequate moral character, insufficient moral motivation or moral identity, inadequate self-controls, and so on (cf. Boyd, Reference Boyd and Puka1994; Kotabe & Hofmann, Reference Kotabe and Hofmann2015; Weaver, Reference Weaver2006); (b) social, including organizational, influences (cf. Burke & Cooper, Reference Burke and Cooper2009; Treviño et al., Reference Treviño, den Nieuwenboer and Kish-Gephart2014); and/or (c) because of aspects of the situation itself such as its moral intensity (Jones, Reference Jones1991), epistemic or ontological uncertainty (McConnell, Reference McConnell2018), or mundane qualities like time pressure.

The study of unethical behavior: Questions that now can be asked

Investigating the structural forms of ethical dilemmas will facilitate contributions to the study of comparative ethics (sometimes called descriptive ethics), which, broadly defined, focuses on ethical commensurability, or “the comparison of [different philosophical] traditions on the matters of how people ought to live their lives, whether [those] traditions have moralities and if so how similar and dissimilar they are” (Wong, Reference Wong2014, Introduction). In other words, such comparisons have heretofore focused only on underlying values and assumptions, beliefs, ethical principles, normative theory, norms, and practices. Using the “content-free” paradigmatic structural forms to classify ethical dilemmas provides another—more descriptive, yet still comparable—basis on which to explore “commensurability.” It enables cross-domain comparisons (of forms of dilemmas) that are not possible at the overt descriptive level because the manifest content of the ethical issues experienced are different in different occupations; professions and their subspecialties; organizations; national, cultural, or demographic groups; age cohorts; and so forth.

For example, one could answer questions such as whether the relative incidence of role-conflict dilemmas differ between corporate coaches and counselors in independent practice, or whether those who work in publicly owned companies experience a higher proportion of coercive dilemmas than do those in privately held [or nonprofit] organizations. What about those in professional practice in comparison with academics? Do they tend to experience different forms of ethical dilemmas? Do we face more coercive pressures in formal hierarchical organizations than in those with flatter structures? Are human resource managers exposed more frequently to role conflict than academic psychologists? Is job level associated with extent of self-serving temptations? Many more comparisons could be cited—some perhaps theoretically driven.

Using the paradigmatic forms will also facilitate longitudinal analyses, despite the fact that the manifest contents of ethical challenges change over time due to technological advances, social policies, economic circumstances, and other transitions that give rise to novel ethical issues. For example, when these survey data were collected in 2009, none of the respondents mentioned any ethical concerns regarding aspects of “big data” analytics, artificial intelligence, or facial recognition analysis, nor was sexual harassment a significant issue. It is likely that the 10-year replication of this survey (in progress) will yield such concerns—yet ethical situations in those domains are no less amenable to the comparative structural analysis described here, thus are commensurable. Similarly, this approach enables meaningful cohort analyses (e.g., how similar are the forms of dilemmas faced now by beginning practitioners to those faced by more senior people at a comparable stage of professional development?) and guidance for professional training (e.g., are there perennially frequent forms of dilemma that should be especially attended to in graduate school?).

Nevertheless, it will certainly remain of interest to researchers and practitioners within a given profession, organization, institution, or other defined population to learn more about the manifest nature (i.e., specific situational details) of endemic ethical challenges. The structural approach is meant to supplement and extend, not replace, content-based descriptions.