Lefkowitz (Reference Lefkowitz2021) developed a taxonomy to address the nuances of the ethical dilemmas that industrial-organizational (I-O) psychologists face due to factors such as changes over time in technology, economy, and other transitions giving rise to novel ethical issues. This structural approach enables comparisons of the ethical dilemmas across various professions, organizations, demographic groups, and so on. To complement this “content-free” structural aspect of ethical dilemmas, we propose that a systematic approach should be developed to help I-O psychologists make ethical decisions. The goal of this commentary is to initiate the dialog of developing a structural approach to ethical decision making in I-O psychology.

Therefore, in this commentary, we first review the New Zealand Psychologists Board’s (NZPB) competence-based ethical training, which seeks to unify different practices of psychology by first providing psychologists with an understanding of the fundamental purpose of the ethical codes and subsequently implementing them in unique situations successfully (NZBP, 2002). Then, we outline a six-step, ethical decision-making model prescribed to use the competencies efficiently. Next, we use the ethical dilemma presented in Lefkowitz’s (Reference Lefkowitz2021) paper (see Appendix A) to provide a template with examples of how the decision-making model can be implemented. Finally, we suggest practical implications and future research to test this approach empirically in the I-O psychology field.

Competence-based ethical training

The New Zealand Psychologists’ Code of Ethics presents ethical codes as an umbrella, acknowledging that no code can be exhaustive in its coverage. These codes serve as a document for the subsequent development of behavioral expectations for different areas of psychology (Sinclair, Reference Sinclair1998). Competence-based ethical training is consistent with these objectives and focuses on the psychologists’ ability to apply the general knowledge and skills of ethical issues in the real world, with competencies as criteria for evaluating learners (Falender & Shafranske, Reference Falender and Shafranske2004; Seymour et al., Reference Sey, mour, Nairn and Austin2004). This approach helps operationalize ethical competencies and assess individuals’ ability to know and apply rules in a consistent fashion.

The NZPB has developed nine core competencies, and the competence-based model explicitly draws upon the principles that are based on these competencies (NZPB, 2018). Moreover, the knowledge and skills that are required for these competencies are outlined in detail to help students understand how psychologists can develop them. For example, competence in communication encompasses the knowledge of techniques for dissemination of findings and the skills to gather relevant information, build rapport, and effective communication of outcomes. Overall, psychologists receive training on and assessment of these competencies and are expected to use them to systematically solve ethical dilemmas. The next section outlines the ethical decision-making model (NZPB, 2002) that enables psychologists to use these competencies systematically.

The six-step ethical decision-making model

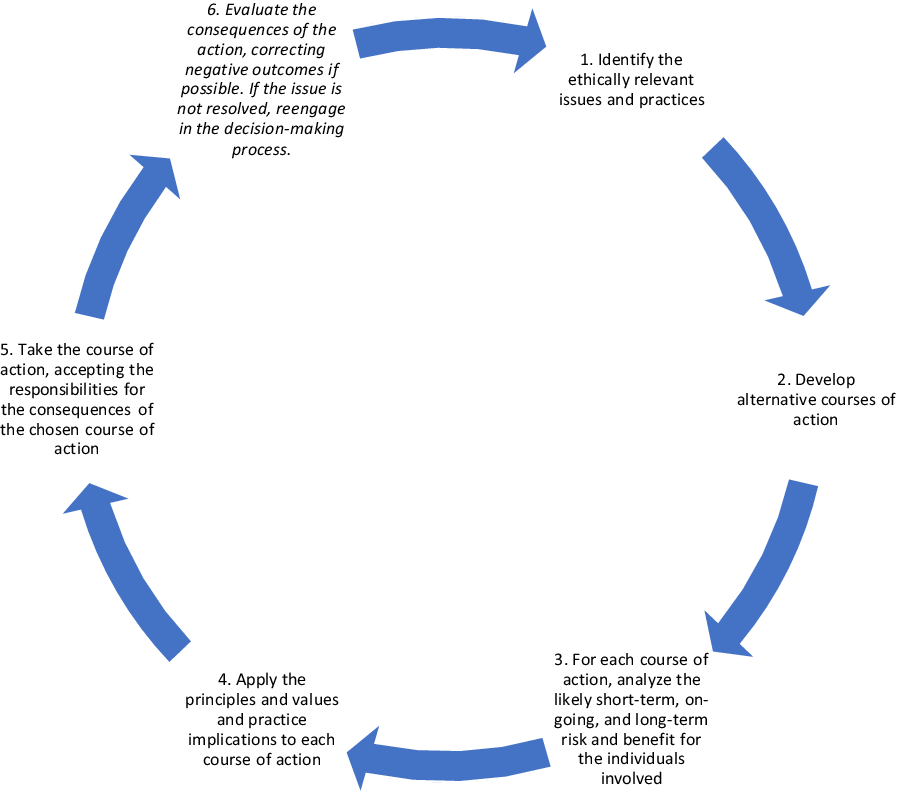

The ethical decision-making model is an educational framework that promotes the understanding of ethical dilemmas as well as a working tool that facilitates ethical decision making (Lincoln & Holmes, Reference Lincoln and Holmes2010; Lindsay, Reference Lindsay, Leach, Stevens, Lindsay, Ferrero and Korkut2012). We acknowledge that there are various ethical decision-making models that are based on the APA ethical code of conduct (e.g., Gottlieb, Reference Gottlieb1993); however, the NZPB’s six-step ethical decision-making model (Figure 1) is consistent with the competence-based training in that it emphasizes the understanding of the fundamental meaning of the codes and identification of issues that may include conflicting principles or interests rather than simply deciding what constitutes obedience to the existing rules.

Figure 1. The six-step ethical decision-making model (New Zealand Psychologists Board, 2002)

It is important to note that a linear approach to solving an ethical issue can sometimes fail to account for unique differences within culture, groups, and organizations (du Preez & Goedeke, Reference du Preez, Goedeke, Rucklidge, Feather, Robertson and New Zealand Psychological2016). Therefore, as demonstrated in Figure 1, we emphasize a nonlinear approach when using this model. When adapting this model to I-O psychology, we reiterate the importance of gathering all the necessary information at step 1 and revisiting this step to ensure that an informed decision is being made. Also, it is critical to account for personal and organizational constraints and code of practice at different workplaces. Although the model provides useful practice-based guidance on how psychologists may manage ethical dilemmas, being aware of factors that may limit the proper use of it (such as limited time or incomplete information) is important.

Ethical decision-making template

Table 1 demonstrates how the six steps in the decision-making model can be applied to a real-life scenario (Appendix A) and help individuals practice competency-based ethical decision making in I-O psychology. In this template, we first outline the issue and list the individuals who could potentially be affected by the decision. Next, we outline the competencies that could be used to analyze the issue. The goal is not to provide an exhaustive list of competencies but to provide an initial list of potential competencies that practitioners could use when brainstorming ideas. Then, we provide a few examples of how the issue can be analyzed and list the subsequent course of actions and the associated benefits, risks, and practice implications. A comprehensive list of all the potential outcomes can help practitioners make prudent and holistic decisions.

Table 1. The Six-Step Ethical Decision-Making Process Template

It is important to note that ethical codes cannot cover every possible situation that may arise, and sometimes ethical standards may conflict with each other, with law, or with organizational guidelines (Nagy, Reference Nagy and Nagy2010). For these reasons, ethical decision-making processes are essential for guiding practitioners on how they may prioritize principles and come to ethically sound decisions. When faced with an ethical dilemma, a psychologist should consider the principles on which the code of ethics is based and the competencies they have developed. Understanding the value and practice implication of each principle thoroughly will allow the psychologist to think through the conflicts that have led to the ethical dilemma and help arrive at an ethically sound decision.

Practical implications

We recommend that practitioners identify the specific competencies that can help them understand ethical dilemmas and efficiently apply solutions using the knowledge and skills that they have developed. Practitioners can use the template provided in this paper to outline a comprehensive overview of the ethical dilemma and use their fundamental understanding of the ethical codes and competencies to brainstorm all the benefits and potential risks of different courses of action. When considering a course of action, it is important to be aware of personal biases, assumptions, and limitations. This awareness can help practitioners listen to clients without judgement and have more clarity in ethical dilemmas. Additionally, the awareness of the limitations of one’s own understanding and competence can prompt practitioners to consult with colleagues and supervisors early on and help resolve any issue that may occur due to conflicts of interest (Thompson & Thompson, Reference Thompson, Thompson, Thompson and Thompson2008).

Future research

Future studies should identify the competencies that are required for ethical decision-making processes in I-O psychology. These competencies can be adapted from the ones developed by the New Zealand Psychologists’ Board and/or O*NET (NZPB, 2018; O*NET, 2018). The knowledge and skills that are required to develop these competencies should be validated to eventually be used as an assessment of a practitioner’s ability to apply them and resolve ethical dilemmas. We suggest using Lefkowitz’s (Reference Lefkowitz2021) approach of recruiting I-O psychologists and using content-validation processes to develop the competencies that are required to make ethically sound decisions.

As mentioned earlier, this model should be used with a nonlinear approach. Therefore, we suggest that competency-based training should be empirically tested against factors such as an organization’s culture, the individual’s tenure, the individual’s decision-making style, and so on to confirm its efficacy in various settings and for different individuals.

Conclusions

Competence-based ethical decision-making training can facilitate continual exposure to making decisions that are ethically sound. The goal of this paper was to initiate this dialog of developing a “content-free” structural framework to help I-O psychologists with the ethical decision-making process. We reviewed an existing model that was implemented by the New Zealand Psychologists’ Board and hope that this model will be adapted in the I-O psychology field and help practitioners commit to making decisions that improve the conditions of individuals, organizations, and society.

Lefkowitz (Reference Lefkowitz2021) developed a taxonomy to address the nuances of the ethical dilemmas that industrial-organizational (I-O) psychologists face due to factors such as changes over time in technology, economy, and other transitions giving rise to novel ethical issues. This structural approach enables comparisons of the ethical dilemmas across various professions, organizations, demographic groups, and so on. To complement this “content-free” structural aspect of ethical dilemmas, we propose that a systematic approach should be developed to help I-O psychologists make ethical decisions. The goal of this commentary is to initiate the dialog of developing a structural approach to ethical decision making in I-O psychology.

Therefore, in this commentary, we first review the New Zealand Psychologists Board’s (NZPB) competence-based ethical training, which seeks to unify different practices of psychology by first providing psychologists with an understanding of the fundamental purpose of the ethical codes and subsequently implementing them in unique situations successfully (NZBP, 2002). Then, we outline a six-step, ethical decision-making model prescribed to use the competencies efficiently. Next, we use the ethical dilemma presented in Lefkowitz’s (Reference Lefkowitz2021) paper (see Appendix A) to provide a template with examples of how the decision-making model can be implemented. Finally, we suggest practical implications and future research to test this approach empirically in the I-O psychology field.

Competence-based ethical training

The New Zealand Psychologists’ Code of Ethics presents ethical codes as an umbrella, acknowledging that no code can be exhaustive in its coverage. These codes serve as a document for the subsequent development of behavioral expectations for different areas of psychology (Sinclair, Reference Sinclair1998). Competence-based ethical training is consistent with these objectives and focuses on the psychologists’ ability to apply the general knowledge and skills of ethical issues in the real world, with competencies as criteria for evaluating learners (Falender & Shafranske, Reference Falender and Shafranske2004; Seymour et al., Reference Sey, mour, Nairn and Austin2004). This approach helps operationalize ethical competencies and assess individuals’ ability to know and apply rules in a consistent fashion.

The NZPB has developed nine core competencies, and the competence-based model explicitly draws upon the principles that are based on these competencies (NZPB, 2018). Moreover, the knowledge and skills that are required for these competencies are outlined in detail to help students understand how psychologists can develop them. For example, competence in communication encompasses the knowledge of techniques for dissemination of findings and the skills to gather relevant information, build rapport, and effective communication of outcomes. Overall, psychologists receive training on and assessment of these competencies and are expected to use them to systematically solve ethical dilemmas. The next section outlines the ethical decision-making model (NZPB, 2002) that enables psychologists to use these competencies systematically.

The six-step ethical decision-making model

The ethical decision-making model is an educational framework that promotes the understanding of ethical dilemmas as well as a working tool that facilitates ethical decision making (Lincoln & Holmes, Reference Lincoln and Holmes2010; Lindsay, Reference Lindsay, Leach, Stevens, Lindsay, Ferrero and Korkut2012). We acknowledge that there are various ethical decision-making models that are based on the APA ethical code of conduct (e.g., Gottlieb, Reference Gottlieb1993); however, the NZPB’s six-step ethical decision-making model (Figure 1) is consistent with the competence-based training in that it emphasizes the understanding of the fundamental meaning of the codes and identification of issues that may include conflicting principles or interests rather than simply deciding what constitutes obedience to the existing rules.

Figure 1. The six-step ethical decision-making model (New Zealand Psychologists Board, 2002)

It is important to note that a linear approach to solving an ethical issue can sometimes fail to account for unique differences within culture, groups, and organizations (du Preez & Goedeke, Reference du Preez, Goedeke, Rucklidge, Feather, Robertson and New Zealand Psychological2016). Therefore, as demonstrated in Figure 1, we emphasize a nonlinear approach when using this model. When adapting this model to I-O psychology, we reiterate the importance of gathering all the necessary information at step 1 and revisiting this step to ensure that an informed decision is being made. Also, it is critical to account for personal and organizational constraints and code of practice at different workplaces. Although the model provides useful practice-based guidance on how psychologists may manage ethical dilemmas, being aware of factors that may limit the proper use of it (such as limited time or incomplete information) is important.

Ethical decision-making template

Table 1 demonstrates how the six steps in the decision-making model can be applied to a real-life scenario (Appendix A) and help individuals practice competency-based ethical decision making in I-O psychology. In this template, we first outline the issue and list the individuals who could potentially be affected by the decision. Next, we outline the competencies that could be used to analyze the issue. The goal is not to provide an exhaustive list of competencies but to provide an initial list of potential competencies that practitioners could use when brainstorming ideas. Then, we provide a few examples of how the issue can be analyzed and list the subsequent course of actions and the associated benefits, risks, and practice implications. A comprehensive list of all the potential outcomes can help practitioners make prudent and holistic decisions.

Table 1. The Six-Step Ethical Decision-Making Process Template

It is important to note that ethical codes cannot cover every possible situation that may arise, and sometimes ethical standards may conflict with each other, with law, or with organizational guidelines (Nagy, Reference Nagy and Nagy2010). For these reasons, ethical decision-making processes are essential for guiding practitioners on how they may prioritize principles and come to ethically sound decisions. When faced with an ethical dilemma, a psychologist should consider the principles on which the code of ethics is based and the competencies they have developed. Understanding the value and practice implication of each principle thoroughly will allow the psychologist to think through the conflicts that have led to the ethical dilemma and help arrive at an ethically sound decision.

Practical implications

We recommend that practitioners identify the specific competencies that can help them understand ethical dilemmas and efficiently apply solutions using the knowledge and skills that they have developed. Practitioners can use the template provided in this paper to outline a comprehensive overview of the ethical dilemma and use their fundamental understanding of the ethical codes and competencies to brainstorm all the benefits and potential risks of different courses of action. When considering a course of action, it is important to be aware of personal biases, assumptions, and limitations. This awareness can help practitioners listen to clients without judgement and have more clarity in ethical dilemmas. Additionally, the awareness of the limitations of one’s own understanding and competence can prompt practitioners to consult with colleagues and supervisors early on and help resolve any issue that may occur due to conflicts of interest (Thompson & Thompson, Reference Thompson, Thompson, Thompson and Thompson2008).

Future research

Future studies should identify the competencies that are required for ethical decision-making processes in I-O psychology. These competencies can be adapted from the ones developed by the New Zealand Psychologists’ Board and/or O*NET (NZPB, 2018; O*NET, 2018). The knowledge and skills that are required to develop these competencies should be validated to eventually be used as an assessment of a practitioner’s ability to apply them and resolve ethical dilemmas. We suggest using Lefkowitz’s (Reference Lefkowitz2021) approach of recruiting I-O psychologists and using content-validation processes to develop the competencies that are required to make ethically sound decisions.

As mentioned earlier, this model should be used with a nonlinear approach. Therefore, we suggest that competency-based training should be empirically tested against factors such as an organization’s culture, the individual’s tenure, the individual’s decision-making style, and so on to confirm its efficacy in various settings and for different individuals.

Conclusions

Competence-based ethical decision-making training can facilitate continual exposure to making decisions that are ethically sound. The goal of this paper was to initiate this dialog of developing a “content-free” structural framework to help I-O psychologists with the ethical decision-making process. We reviewed an existing model that was implemented by the New Zealand Psychologists’ Board and hope that this model will be adapted in the I-O psychology field and help practitioners commit to making decisions that improve the conditions of individuals, organizations, and society.

Appendix A Ethical dilemma

While consulting in a large organization, I was asked to initiate several coaching and development assignments with two senior executives. Several discussions and meetings occurred with the senior executives, the CEO, and the SrVP-HR to get agreement on the confidentiality ground rules for the engagements. After 3 months into both assignments, the CEO pressured me to divulge assessment and coaching information that was clearly covered in our agreement as confidential to the participant. He implied that my future work in the company might be in jeopardy if I did not cooperate with his request. After some thought, I chose not to share the information.

Source: Lefkowitz, J. (2021). Forms of ethical dilemmas in industrial-organizational psychology. Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice, 14(3), 297–319.