The complexity and speed of an increasingly turbulent business environment (e.g., competitive pressure, M&A, expansion, cost reduction, technology, etc.) has contributed significant pressure on organizations by requiring more rapid and constant change than ever before. Some of the more disruptive changes for a company come from the external environment in which the organization operates. The magnitude of change in the current healthcare environment (e.g., regulatory, demographic, delivery and payment systems/technology, consolidation, etc.) is transforming America's healthcare industry and, in turn, has accelerated a pivot in Humana Inc.’s long-term strategy. Critical for Humana's success, now more than ever, is implementing a new integrated model of care (including rewarding providers for managing costs and delivering quality care), enhancing the consumer experience, and improving the well-being of the communities we serve. This is a major departure from traditional strategies found in the healthcare insurance industry, and Humana quickly recognized that this required significant changes for the company and its employees. The business need was to ensure the organization had the agility needed to quickly execute this strategic course change successfully. This required industrial and organizational (I-O) practitioners to develop and build robust and innovative change readiness and change management capabilities for Humana.

However, successfully managing change for large organizations has always been difficult, even under the best circumstances. In response, a number of change management models have evolved over the past 3 decades to help organizations manage change more effectively. One of the most popular of these approaches (Mento, Jones, & Dirndofer, Reference Mento, Jones and Dirndorfer2002) is Kotter's (Reference Kotter1996) eight-stage process, which addresses organizational change as a process that moves from one fixed state to another through a series of preplanned steps. Large numbers of organizations (including Humana) have adopted Kotter's model, or some variation of it, as their preferred methodology to manage change (Brisson-Banks, Reference Brisson-Banks2010). Despite the popularity of these models, practitioners have found that planned change models are often slow, static, best suitable for times of stability, and fail to consider critical issues such as the continuous need for employee flexibility (Hatch & Cunliffe, Reference Hatch and Cunliffe2006; Kanter, Reference Kanter1999). Over the years, we have experienced similar results with our large-scale change efforts and have identified a number of organizational barriers that often produce unintended consequences regarding planned change. These barriers include organizational culture (e.g., change-resistant culture), structure (e.g., size, distribution, spans, and layers), process (e.g., different change models, tools, and language), talent (e.g., inexperienced change practitioners), and focus (e.g., organization versus individual). As a result, we have found that facilitating organizational change with a planned change management model often fails to meet our stated objectives. Based on this experience, it was no surprise to us that a 2008 IBM study of more than 1,500 change practitioners and researchers found that only 41% of change projects met their objectives regarding time, budget, and quality (Jorgensen, Owen, & Neus, Reference Jorgensen, Owen and Neus2008). The remaining 59% missed at least one objective or failed completely. Perhaps the most important finding of this research was that a detailed analysis of the results showed that success of the change efforts depended largely on people, not on process or technology. As Wolf (Reference Wolf2011) asserts, “Models of planned change may no longer be sufficient to address the needs of today's organizations. The world no longer moves in incremental steps, but rather in significant leaps that call for new modes of effecting change” (pp. 20–21). In today's turbulent, fast-paced business environment, even Kotter has acknowledged that the change strategies that may have worked in the past are currently failing organizations (Kotter, Reference Kotter2012). For Humana, it was clear that if our organizational transformation was to succeed, we needed to complement our standard change practices with a new approach.

At the same time, several authors have suggested that organizational agility is imperative for organizations to remain competitive, profitable, and able to successfully execute on new initiatives (McKinsey, 2010; Project Management Institute, 2012). One required element of organizational agility is an agile workforce: a well-trained and flexible workforce that can adapt quickly and easily to new opportunities and market circumstances (Muduli, Reference Muduli2013). Muduli identified several common attributes of an agile workforce, which closely match the attributes of organizational agility reviewed in Charbonnier-Voirin (Reference Charbonnier-Voirin2011). These attributes include proactivity (the initiation of activities that have a positive effect on a changed environment) and adaptivity (changing or modifying oneself or their behavior to better fit in the new environment, which includes flexibility to pursue different tactics and to quickly change from one strategy to another). Collaboration, cooperation, knowledge sharing, and employee empowerment are also noted as hallmarks of an agile organization and agile individuals. All of these attributes are key elements of successful employee involvement in organizational change efforts.

To complement our planned change approaches as well as build organizational agility, we proposed focusing on individual agility by equipping our employees with the skills to proactively identify and implement change when needed. After all, successful organizational change depends on persuading hundreds (or thousands) of individuals to think differently. In fact, research has found a positive relationship between individual behavioral change and organizational change outcomes (Robertson, Roberts, & Porras, Reference Robertson, Roberts and Porras1993). Our goal was to help employees better understand and manage their own reactions to change by providing them with a simple approach that was both easy to remember and practice.

We would be remiss to address agility and change without focusing on the stress that is often associated with change. Research has suggested that workplace stress is responsible for at least 120,000 deaths per year and between 5% and 8% of annual healthcare costs in the United States (Goh, Pfeffer, & Zenios, Reference Goh, Pfeffer and Zenios2016). In addition, the American Institute of Stress reports that workplace stress carries a price tag for US industry estimated at over $300 billion annually as a result of accidents, absenteeism, employee turnover, workers’ compensation awards, and diminished productivity. Resilience enables individuals to recover after experiencing stressful life events, such as significant change, adversity, and hardship (Warner & April, Reference Warner and April2012). In the study of stress, trauma, setbacks, and challenges, resilience has emerged as a key differentiator between those who “bounce back” and those who do not. In fact, one of the hallmarks of highly resilient individuals is the ability to emerge from setbacks stronger than before the challenging event or situation (Coutu, Reference Coutu2002; Reivich, Seligman, & McBride, Reference Reivich, Seligman and McBride2011; Seligman, Reference Seligman2011). In response, organizations and the people who lead them have focused on improving their personal resilience. In a recent study of over 470 North American companies, McCann, Selsky, and Lee (Reference McCann, Selsky and Lee2009) found that companies with greater levels of organizational agility and resilience were more competitive and profitable, even in highly turbulent environments. These researchers also concluded that “Pursuing agility without investing in resiliency is risky because it creates fragility—unsupported exposure to surprises and shocks” (McCann et al., Reference McCann, Selsky and Lee2009, p. 45).

Having implemented traditional change management methodology with varied success, we saw an opportunity to develop individual change readiness skills in our workforce. To achieve this, we designed, developed, and deployed a change readiness program that would assist our employees to view change as positive, identify and act on opportunities to change, and manage change in a personally healthy way. The resulting program (FIT for Change™; FIT = Feel, Innovate, Take Action) was deployed using multiple channels including a 4-hour classroom experience, virtual facilitated web sessions, and as a self-directed learning experience. In our approach to build this program, we solicited input from our employees via focus groups. One of the most important things we learned from this exercise was employees’ expressed desire to know where they stood in terms of their own agility and resilience so they could focus on their own improvement. In response, we developed and validated a change readiness assessment of individual agility and resilience. We believed this would supplement the learning program by providing employees feedback they could use for development planning, and we could use this information to assess change in employees’ readiness. Our goal was to minimize the reliance on traditional change management approaches, reduce disruption brought on by change, and create a supportive environment where workers proactively look for opportunities to improve because they have the skills to deal with change in a positive manner. If organizations add a focus on building the skills of agility and resilience at the individual level, workforces will be more effective at implementing change initiatives. More importantly, a workforce skilled at practicing agility is more likely to initiate change (as the environment indicates) in order to remain effective, making change a natural part of organizational operations. In the sections below, we define the change readiness assessment in detail, outline several potential antecedents and correlates of the assessment constructs that were used in its validation and that have implications for managing change, discuss the validation procedures and results, present the results of its initial application, and discuss the implications of our work.

Definitions, Correlates, and Criterion

As a novel approach to change management, no existing scales were found that matched the current definitions of resilience and agility. Therefore, design of the research was focused on validating new measures. Potential antecedents, or correlates, and consequences of agility and resilience are discussed and used for validation support. These are also discussed as potential components of the measurement instrument for use in practice to provide guidance for individuals’ development and their knowledge of potential outcomes. Note, however, that the research design used does not provide clear support for causation.

Definitions and Criterion

Consistent with existing research on agility at the organizational level of analysis (Charbonnier-Voirin, Reference Charbonnier-Voirin2011; Muduli, Reference Muduli2013), agility at the individual level of analysis was defined as the skill to proactively create opportunities or overcome obstacles by rethinking or redefining typical approaches. Agility involves monitoring the current environment to anticipate change and responding in a timely and effective way when changing circumstances require it. Agility is a skill that can be developed, and agility takes effort on the part of the individual to monitor the environment and proactively make changes; both factors that can create stress for the individual. Existing theory and research suggests that agility is positively related to individuals’ stress (McCann et al., Reference McCann, Selsky and Lee2009).

Because fostering agility could increase stress, the change readiness program also sought to develop individual resilience to help offset this increase (Coutu, Reference Coutu2002; McCann et al., Reference McCann, Selsky and Lee2009, Reivich, Seligman, & McBride, Reference Reivich, Seligman and McBride2011; Seligman, Reference Seligman2011; Warner & April, Reference Warner and April2012). Resilience at the individual level of analysis has been defined as the emotional and psychological transition related to change (Bridges, Reference Bridges1980), responding effectively to either mitigate stress caused by the change, or managing or reducing increased stress. Resilience can take many forms, including cognitive (e.g., framing), emotional, or behavioral. Stress is proposed to be related to both agility and resilience, with agility positively related to stress and resilience negatively related to stress.

With organizational agility considered as a contributor to a company's success, it is reasonable that individual agility would be valued by the organization. Although for some, agility may be part of existing role requirements, such as those in top leadership positions, it is likely outside the explicit job scope for many positions. If individual agility is truly beneficial to the organization's performance (e.g., proactively making needed changes in response to the environment), then an individual's skill with agility could impact evaluation of his or her performance, even if it is not an explicit role requirement, functioning similar to organizational citizenship behavior (e.g., Borman & Motowidlo, Reference Borman, Motowidlo, Schmitt and Borman1993; Podsakoff, Whiting, Podsakoff, & Blume, Reference Podsakoff, Whiting, Podsakoff and Blume2009). Agility is proposed to be positively related to job performance.

Correlates

To create a more holistic approach to developing agility and resilience, the measurement instrument included potential antecedents or correlates. Although some variables are theoretical antecedents, their true relationship, for example to the resilience–stress relationship, may be covariate. The existing literature identifies several potential antecedents, sometimes attributed to both agility and resilience. In 7 of the 10 studies highlighted by Charbonnier-Voirin (Reference Charbonnier-Voirin2011), collaboration, cooperation, and/or work relationships were identified as characteristics of agility. Presumably, building collaborative relationships with others across an organization provides needed information to monitor the current environment, much of which is outside individuals’ day-to-day surroundings and fosters the effectiveness of making changes to policies, procedures, and practices (Charbonnier-Voirin, Reference Charbonnier-Voirin2011). Specifically, collaboration with others outside of one's own area of the organization may be an antecedent to agility, recognizing that collaboration may also be a covariate, with high agility leading to high collaboration. Cross-organizational collaboration is proposed to be positively related to agility.

Including potential antecedents for resilience is especially important, as resilience is a general tendency and, therefore, may be more difficult for an individual to change. Including possible antecedents provides individuals with additional areas for focused development, recognizing that the current research design does not support causation. With resilience defined as an individual's tendency to respond effectively to either mitigate stress caused by change or manage or reduce increased stress, there are many individual traits and behaviors that may serve as antecedents or correlates (American Psychological Association, 2016). There is extant evidence on the effectiveness of various behavioral and cognitive-emotional approaches, such as physical activity, social support, and mindfulness practices (Cohen-Katz, Wiley, Capuano, Baker, & Shapiro, Reference Cohen-Katz, Wiley, Capuano, Baker and Shapiro2004; Hunter & McCormick, Reference Hunter, McCormick and Newell2008; Schwartz & McCarthy, Reference Schwartz and McCarthy2007; Southwick & Charney, Reference Southwick and Charney2013), and the connection between social support and work-related stress and burnout is well supported (e.g., Etzion, Reference Etzion1984; Halbesleben, Reference Halbesleben2006). According to Warner and April (Reference Warner and April2012), the ability to both give and accept support was a core enabler of resilience. We focused on behavioral strategies relevant to the work environment that were commonly identified in resilience literature: the availability of social support (the degree to which one receives support from others and has strong social networks), individual renewal strategies (characterized by deliberate practices to renew energy depleted by stress, such as physical activity), and creating positive relationships (through respect, authenticity, and providing support to others).

Openness to experience, one of the “big five” personality dimensions (e.g., McCrae & John, Reference McCrae and John1992), has been related to stress or related constructs, such as burnout (e.g., Alarcon, Eschleman & Bowling, Reference Alarcon, Eschleman and Bowling2009; Baer & Oldham, Reference Baer and Oldham2006). Williams, Rau, Cribbet, and Gunn (Reference Williams, Rau, Cribbet and Gunn2009) found a relationship between openness to experience and stress regulation, such that individuals high in openness to experience have greater stress resilience. These results seem to indicate the individuals high in openness to experiences have greater receptivity to their environment. This trait presumably predisposes them to view change as less of a threat, thus creating less stress when change does occur.

Methods, Results, and Application

Because many of the scales contained new items or were new measures, a multistep approach was taken for measurement instrument development. The instrument's psychometric properties were tested with an initial sample, adjusted, and cross-validated with a second dataset.

Initial Measurement Development

The initial sample was limited to employees exempt from the Fair Labor Standard Act (Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938), which is the population for whom the measurement instrument and related change readiness program were developed. A random sample of 1,659 employees was invited to participate via an email invitation, utilizing a third-party survey service provider. The questionnaire was described as being for research purposes only. Complete questionnaires were received from 784 respondents (47% response rate). Demographic representation of the respondents was similar to the population from which the sample was drawn (e.g., tenure, age, gender). Of the 784 respondents, 221 (28.2%) supervised at least one employee. Additional demographics are not provided to protect confidentiality of company information.

The questionnaire consisted of 46 items, which were intended to assess seven dimensions:

-

1. Agility (fourteen items)

-

2. Resilience (nine items)

-

3. Individual renewal (three items; behavioral actions)

-

4. Collaboration (eight items; collaboration outside of one's own team or department)

-

5. Creating positive relationships (four items; support provided to others)

-

6. Openness to experience (three items)

-

7. Social support (five items; support received from others)

Participants were instructed to “Please use the rating scale below to indicate how accurately each statement describes you. Describe yourself as you generally are now, not as you wish to be. Describe yourself honestly, knowing that your responses will be kept confidential. Please read each statement carefully, and then select the response that best fits you.” Responses to each item were on a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = very inaccurate, 2 = inaccurate, 3 = neither accurate nor inaccurate, 4 = accurate, 5 = very accurate).

The scales for agility and resilience were created for our change readiness assessment. Consistent with the definition of agility, the 14-item scale included two subscales (five items related to monitoring the environment and anticipating need for change, and nine items related to proactively acting and initiating change). A scale for individual renewal (the extent to which one takes action, such as taking breaks from work to stay energized and reduce stress, relevant to the work context) was also created. Although the term “individual renewal” may be new, the concept is not (American Psychological Association, 2016). There are existing measures for collaboration; however, they did not align with the current definition (collaboration with others outside of one's own team or department), and therefore, a scale was also developed. Openness to new experience, social support, and creating positive relationships scales were adapted from existing measures (Barrera, Sandler & Ramsay, Reference Barrera, Sandler and Ramsay1981; Goldberg et al., Reference Goldberg, Johnson, Eber, Hogan, Ashton, Cloninger and Gough2006; International Personality Item Pool, n.d.; Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, Reference Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet and Farley1988), with adjustments made for use in a workplace context.

Initial Measurement Model

The initial sample was randomly divided into two datasets, each consisting of 392 respondents. Using the first dataset, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to examine the psychometric properties of the instrument (Brown, Reference Brown2006; Van Prooijen & Van der Kloot, Reference Van Prooijen and Van der Kloot2001). Data were analyzed by the method of principal-components analysis with varimax rotation. Initial results indicated a latent structure consisting of nine components, partially corresponding to the intended seven. Two of the components comprised items from various scales and, therefore, were removed from the model. Results also indicated the need for improvement, with some items having unsatisfactorily low loadings on the intended component (e.g., less than .50) and/or high cross-loadings on different components (e.g., greater than .35). Additionally, Cronbach's alpha estimates of internal reliability were performed for each component to assist in scale adjustment. The subscales for agility were not supported, with items either loading together or loading on one of the two components that were removed. The remaining seven components aligned with the proposed measurement model. After making adjustments, the measure consisted of 33 items. Internal reliability for each scale was above .70.

Using the remaining 392 responses from the initial sample, factor analysis was repeated to confirm results of the adjusted model. The analysis resulted in the same seven-factor solution with all items loading similar to the initial, adjusted model. The analysis accounted for 63.0% of the total variance, and item factor loadings were .50 or above on the intended scale, with no cross-loadings of greater than .35. Internal reliability estimates for each scale were above .70. Table 1 includes the final scales and corresponding item factor loadings. Table 2 includes the mean, standard deviation, and internal reliability of each scale, along with correlations.

Table 1. Factor Loadings for All Measures in Final Model

Table 2. Means, Standard Deviations, Correlations, and Internal Reliability

Note: All rs > .10, p. < .05. Figures in parentheses are internal reliability estimates, n = 392.

Measurement Model Cross-Validation

The cross-validation sample consisted of 715 participants from the change readiness program for which the instrument was developed. These data were collected over a 4-month period commencing after completion of the initial measurement model development. Instructions to the participants were similar to the initial sample except that the questionnaire was described as being for the change readiness program and participants were provided individual results reports. The sample demographics were similar to the larger population (e.g., similar tenure, age, gender) with the exception that there was greater representation of people leaders, with 77.5% of participants supervising at least one employee.

Factor analysis was conducted to confirm results of the initial measurement model. The analysis resulted in the same seven-factor solution with all item loadings confirming the measurement model. One agility item had a factor loading below the desirable level of .50 but with acceptable loadings across other factors. The analysis accounted for 59.1% of the total variance, and internal reliability estimates for each scale were above .71. Results were similar to those shown in Tables 1 and 2. For the cross-validation sample, age (correlation) and gender (mean difference) were not significantly related to agility or resilience (p < .05).

Criterion Analysis

Stress data were available on 347 of the initial sample participants. The stress data were collected approximately 3 months prior to data collection for the current study, within the general timeframe for which stress data are considered accurate (making it relevant for the initial sample participants but not for the cross-validation sample). Stress was assessed by a one-item measure adopted from the American Psychological Association (e.g., American Psychological Association, 2016): “On a scale of 1 to 10 where 1 means you have ‘little or no stress’ and 10 means you have ‘a great deal of stress,’ how would you rate your average levels of stress during the past month?”

As proposed, resilience was negatively correlated with stress (r = –.20, p < .05); however, agility was not significantly related to stress (r = .02, p > .05). This finding supports the premise that resilience can help an individual function efficiently under the stress of a change (Bridges, Reference Bridges1980; Charbonnier-Voirin, Reference Charbonnier-Voirin2011; Muduli, Reference Muduli2013), noting that the current evidence is only correlational. Results did not support the proposed relationship of agility to stress. It is possible that the effort involved in monitoring the current environment and initiating change (Charbonnier-Voirin, Reference Charbonnier-Voirin2011) does not increase stress, which is contrary to extant literature on the relationship between change and stress. However, it was noted that, when resilience is high (i.e., top third on the resilience scale), agility was significantly related to stress (r = .23, p > .05). For purely exploratory purposes, an analysis was conducted to test for an interaction effect between agility and resilience. If agility and resilience are both related to change, with one increasing the related stress and the other decreasing it, it is reasonable that they may interact.

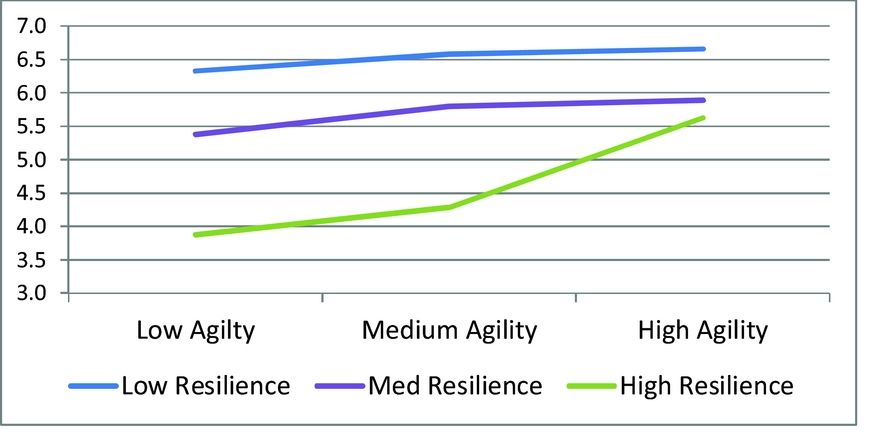

Main effects are shown in Table 3. Contrary to the correlation analysis, both resilience (b = –1.30, p < .05) and agility (b = 0.64, p < .05) predicted stress when entered together in the regression analysis. As noted in Table 4, the interaction effect (b = 0.16, p < .05) was significant beyond the main effect of resilience (b = –1.92, p < .05) but was not significant when both resilience and agility were entered on the first step of the model, prior to entering the interaction. Although not fully supported by these analyses, Figure 1 shows the nature of the interaction effect: When resilience is practiced at a high level, there is a relationship between agility and stress; when resilience is low, stress is high regardless of the agility level. Although this analysis was exploratory and requires additional research, these findings imply that resilience on its own is an important focus for practitioners and even of greater importance under conditions of high agility and change.

Table 3. Main Effects for Resilience and Agility Predicting Stress

F = 10.58; Adjusted R2 = .06.

Table 4. Interaction Effects for Resilience and Agility Predicting Stress

F = 10.75; adjusted R2 = .06.

Figure 1. Stress (y axis) by agility × resilience interaction.

Standardized supervisor performance ratings were available on 674 of the cross-validation sample participants. Performance ratings were collected throughout the year as a routine business practice. The performance ratings had significant, negative skewness (–.311) and range restriction, with a low frequency of ratings on the low end of the performance scale. Therefore, analysis included only above average performance and average performance ratings, creating a dichotomous variable. (No descriptive information is provided to protect confidentiality of company information.) As proposed, there was a significant difference in agility for above average performance (M = 67th percentile, SD = 24.24%) and average performance (M = 62nd percentile, SD = 26.39%); t (672) = –2.408, p = .01. (Note: In practice, agility scores are reported in percentile using initial sample as normative database.) Resilience was not significantly related to performance, as expected. We have replicated these results multiple times, including an analysis using the initial development sample (not shown). Agility has been described as critical to business success and of growing importance to leaders. These results suggest that, within Humana, supervisors, either implicitly or explicitly, consider agility in evaluating performance.

Correlate Analysis

Using data from the initial sample, as proposed, agility was positively related to collaboration (r = .54, p < .05), and resilience was positively related to social support (r = .42, p < .05), individual renewal (r = .28, p < .05), creating positive relationships (r = .56, p < .05), and openness to new experience (r = .56, p < .05). However, review of Table 2 shows that all of the measures were correlated. First, this can be interpreted as consistent with literature that has sometimes attributed common characteristics to both agility and resilience, as highlighted by McCann et al. (Reference McCann, Selsky and Lee2009). Alternatively, the findings may be attributable to all variables being measured via a single administration, self-report instrument, resulting in common method variance artificially inflating the relationships (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003).

The true nature of the relationships may be a mix of these factors. To help clarify, stepwise regression was conducted on both resilience and agility, allowing all variables to enter the equation. Agility was predicted by collaboration (b = 0.47, p < .05) and resilience (b = 0.39, p < .05); F = 229.58, adjusted R2 = .39. Resilience was predicted by creating positive relationships (b = 0.32, p <.05), openness to new experience (b = 0.31, p < .05), agility (b = 0.22, p < .05), individual renewal (b = 0.08, p < .05), and social support (b = 0.05, p <.05); F = 163.64, adjusted R2 = .51. These analyses were repeated with the cross-validation sample. Findings were consistent, except that individual renewal and social support did not enter in the regression equation for predicting resilience. These findings are also consistent with the literature and proposed relationships.

If the correlates to resilience are antecedents, their relationship to stress should be mediated. Each of the correlates (creating positive relationships, openness to new experience, individual renewal, and social support) had significant bivariate relationships to stress, ranging from r = –.13 to –.27, p < .05. When entered individually on regression analysis, after resilience, only individual renewal continued to have a significant relationship to stress (R2 = .09, resilience b = –0.13, individual renewal b = –0.23, p <.05), indicating that, if it is an antecedent, it also has a direct effect on stress.

Figure 2 summarizes the theoretical psychometric model guiding the instrument used in the change readiness program. These results indicate that individual agility, similar to organizational agility, is related to performance, while it also has a relationship to resilience and stress. Results indicate that a focus on agility without a focus on resilience could lead to negative impact on employees with increased stress levels and, ultimately, less than optimal results. Results also suggest that practitioners should focus on the antecedents or correlates that help build individual agility and resilience. It is suggested that, prior to use, practitioners test the validity of this model in their own organizations, just as the model will continue to be researched and refined for use in Humana.

Figure 2. Measurement instrument theoretical model for use in practice.

Incorporating the Assessment Into Program Design

Upon registering for the change readiness program, participants are sent a link to complete the agility/resilience assessment 3 weeks prior to their scheduled program date. Assessment administration and delivery of results are fully automated. Results are sent to participants 2 days prior to class and include a brief description of percentile ranks, a reminder that this is a self-assessment (how they evaluate their own actions and attitudes), and tips for interpretation and reflection. Individual scale results include a description of the scale and their scores presented as percentile rank. The percentile rank is represented as a circle on a line with a brief descriptor on each end. Each scale also includes behavioral descriptors regarding what “less” and “more” of the characteristic may look like (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Individual assessment report scale example.

Representing results this way was a lesson learned for us. We quickly found that people were reacting negatively to low percentile scores, and we were spending too much time explaining percentile ranks, self-assessment, and why individuals may be misinterpreting their own self-evaluations. Another important item we learned was to link the program design tightly to the assessment so that each program section addressed a portion of the assessment (e.g., concepts, tools, tips for improvement, etc.). Program facilitators review results early in the learning experience so that participants can understand their own results and focus on what they need to work on during the program. Participants are encouraged to share their results and insights with others, and we offer group results for intact teams. Our program evaluation results indicate that employees prefer attending the program as an intact team. It seems that group discussions are more candid and often lead to insights that allow employees to take action as a team.

Initial Organizational Impact

After developing a deployment and marketing strategy, we have delivered the change readiness program and assessment to over 1,200 employees. Our initial evaluation of the program has been encouraging. First, we have experienced very positive feedback and tremendous pull for the program across the enterprise. Second, test–retest results (after 3–4 months) have shown increased scores in nearly every assessment dimension. Finally, we have completed Level 3 evaluations (transfer of learning and behavioral change; Kirkpatrick & Kirkpatrick, Reference Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick2016) on a sample of employees (just over 300 with 107 respondents) 6 months post-program. Our results show over 70% agreement in applying learned concepts and navigating change more effectively, and 54% agreement when asked whether their team and/or customers have been positively impacted as a result of the program.

Discussion

A recent survey found that 91% of over 300 participating companies responded that they were experiencing significant change defined as M&A, significant restructuring, or senior leader transition (Corporate Executive Board, 2016), and our organization is certainly no different. This same study found that of the thousands of leaders surveyed, only about one-third of them were adapting quickly enough to keep pace with their shifting strategy and business goals. It is all too apparent that leaders today are faced with increased uncertainty as markets and industries encounter faster and more complex change than ever before. This environment demands a fundamental shift in how leaders manage change—one that requires a workforce equipped with the agility and resilience that leads to more positive responses to change. This research provides a psychometrically sound measure to assess employee agility and resilience. Practical uses of this measure include building self-awareness of one's own agility and resilience that can be used in HR training and interventions, particularly with individual change readiness.

Our overall results suggest that individual resilience can mitigate the stress associated with the increased demand for agility. That finding alone could have a tremendous impact on a company's organizational health as well as its profitability. Additional research is needed to determine how to develop individual resilience, including incorporating mindfulness and other techniques and strategies, and how to assess the impact of these interventions on other business indicators such as a reduction in absenteeism or reduced resistance to change. Ultimately, longitudinal research is needed that links workforce agility with organizational profitability, effectiveness, and adaptability to rapid change.

Additional Lessons Learned

Developing measurement scales in an applied setting can present some unique challenges for practitioners. On one hand, it is always advantageous to validate an instrument with a sample from the target population. On the other hand, when trying to avoid the use of questionnaire data, which can lead to false conclusions (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003), it can be a challenge to access appropriate, criterion-type data for use in the validation analyses. For the current study, we were fortunate that stress data were available, and that they had been collected within a timeframe near enough to our study to make it valid. Performance ratings are an additional challenge. As with most corporate performance ratings, our data had range restrictions, with ratings skewed to the lower end of performance. To compensate, the ratings were converted to a dichotomous variable, removing the below-average ratings. These ratings are also collected throughout the year, which results in some ratings being “older” than others. Therefore, to build confidence in the conclusions, our analysis has been replicated multiple times as groups of employees take the assessment. One criteria variable likely available in most organizations is employee turnover, but that, of course, requires both a longitudinal study and theoretical relevance. With a little creativity and work, criterion-type data are likely available within practitioners’ organizations in one form or another. Recognizing that the data will often be less than perfect, any analysis plan should control for this by using techniques such as replication to ensure the findings are valid.

Some of the instrument's scales represent skills that can be directly developed, whereas others represent tendencies or dispositions used to create awareness and, possibly, the development of tactics to ensure these tendencies do not hamper effectiveness. In practice, making this distinction clear to program participants can be challenging. Employees sometimes react to the trait-type scales rather than accepting the assessment as feedback for self-awareness. To increase likelihood of acceptance of assessment results and effective development plans, a few considerations include the following:

-

1. Timing: Distributing assessment results far enough in advance of the change readiness class to allow initial reactions to subside but not so far in advance to allow misinterpretation of results to get ingrained or lead to ineffective action. Otherwise, we have found that some participants are fixated on their results rather than what they can do to change them. We have found that 2 business days is optimal.

-

2. Communication: Beginning with the individual feedback report, providing clear directions on what to do with the results and what not to do, and encouraging participants to wait until they attend the class before making any behavioral changes is critical.

-

3. Facilitation: The sensitive content of the change readiness program, including the assessment results, requires a unique facilitation skillset. Program participants often (and are encouraged to) relate what they are learning to personal change they experience in their daily lives, which can be a powerful personal and group experience. We have found that facilitators must be prepared to handle these responses effectively.

We have also discovered additional benefits of the assessment, beyond its initial objectives. Because the program (and assessment) has been delivered to a number of intact teams, which has been the preference of participants, we have found that leaders are interested in exploring their team's agility. This has interesting practical implications for organizations as a whole. Identifying business functions with higher agility levels can help influence corporate strategy by targeting strategic transformations for areas that may be primed to absorb change more quickly. In addition, the instrument may also serve as a needs assessment that allows organizations to identify groups with low agility and/or resilience, and who could benefit from additional training.

Today's business environment is increasingly unpredictable and ever changing. Organizations across all industries are experiencing mounting pressure to react quickly to changing customer demands, market conditions, or new technology. By building organizational agility, or what some researchers have referred to as “adaptive capacity” (McCann et al., Reference McCann, Selsky and Lee2009), organizations may be better equipped to manage or moderate change, volatility, and uncertainty. A critical component of any organizational strategy to build agility is shifting individuals from fear of change to excitement about new opportunities or expanding skills. Developing individual agility and resilience has the potential to complement current change management strategies to help organizations execute strategy and accelerate performance. Organizations that disrupt their environment without this capability may do so at their own risk.