Research–practitioner-based leadership approaches

The breakthrough in research within the industrial sector was the Hawthorn studies conducted by Mayo (Reference Mayo1930). The researcher realized that workers were more productive when they were observed and felt they were of value to the organization. With Mayo's different perspective of workers and supporting the worker to be valued as a social aspect of production gave rise to the human relations movement. As part of the human relations movement was McGregor with his writing “The Human Side of Enterprise” in 1960. McGregor introduced his “Theory X and Theory Y” (McGregor, Reference McGregor1960, Reference McGregor2000; see also Burke, Reference Burke2011), which are concerned with two opposing views of employees: Theory X, in which employees dislike work and need direction and close, authoritarian supervision (Landis, Hill, & Harvey, Reference Landis, Hill and Harvey2014; McGregor, Reference McGregor2000); and Theory Y, in which employees are motived to work and serve the organization. Inspired by Maslow (Reference Maslow1943), McGregor took on a humanistic perspective toward employees and their work attitudes. He opined that people are motivated to reach higher potentials and satisfy their needs through work (Bobic & Davis, Reference Bobic and Davis2003). McGregor called for “humanism to shape the future of management” (Reference McGregor1960, p. 554; also see Pirson & Lawson, Reference Pirson and Lawson2010).

Parallel during the 1960s were the International Harvester Studies as building blocks in I-O psychologists’ work in manufacturing environments. Fleishman (Reference Fleishman1998) conducted surveys in the Harvester trucking company, which developed into pre- and post-training assessments of foremen's consideration of workers and being effective supervisors. Further studies resulted in recognizing that leadership quality is complex and differs from one individual supervisor to another. The conclusion was that leadership effectiveness depends on training outcomes, personality, and situations (situations describe the climate the foreman works in). Hence, these studies laid the foundation for studies on organizational climate and culture.

Continuing with McGregor's rather humanistic perspective, Argyris (Reference Argyris1957) viewed the treatment of employees as an essential aspect of the success of an organization. At first, his belief was that employees’ needs stood against organizational needs (Bonjean, Reference Bonjean1963). But with his “dedication to reducing injustice” (Argyris, Reference Argyris2003, p. 1178), he took on the notion that injustice was founded on workers not being heard, therefore errors were not uncovered, and actions were not taken to solve the immediate problem. Argyris viewed this as knowledge cycling in a single-loop learning process. The inclusion of assumptions into the loop of action and consequences evolves into double-loop learning (Argyris, Reference Argyris1999). The single-loop and double-loop learning concepts were fundamental in Argyris's organizational learning theory that he, together with Schön (Reference Argyris and Schön1989), investigated through participatory action research (Lewin, 1946/Reference Lewin2010; also see Kristiansen & Bloch-Poulsen, Reference Kristiansen and Bloch-Poulsen2017). One such research-consultative project was Lazes's Xerox case, where Argyris and Schön had workers and management collaborate, resulting in a change regarding how the company defined productivity—a move away from productivity-per-worker to organizational productivity (Argyris & Schön, Reference Argyris and Schön1989).

Out of organizational learning, Argyris and Schön paved the way to the learning organization that came to fruition through Senge's (Reference Seng1994) book, The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of The Learning Organization, which was first published in 1990. The five disciplines, or dimensions, of a learning organization are systems thinking, personal mastery, mental models, building shared vision, and team building. Even though Senge (Reference Seng1994) and Schein (Reference Schein1997) gave examples of success stories of major and well-known companies, gaps to the prominently research-based leadership concepts have been identified. Fillion, Koffi, Ekionea, and Booto (Reference Fillion, Koffi, Ekionea and Booto2015) viewed several outcomes of companies that claimed to be learning organizations and found that the majority have implemented changes, but either just a few of the five disciplines, or disciplines have been dealt with separately. Inclusion of five disciplines at all times calls for a systemic thinking, which is complex and takes time. The time aspect may have been why only a few manufacturing companies integrated organizational learning into their overall management systems.

Law and Chuah (Reference Law and Chuah2004) took the concept of the learning organization and developed a project-team–based learning framework that they named project-action learning (PAL). The premise of PAL is to progress through team learning processes that entail a performance goal, which conducted through a project, and a learning goal. Of interest are team performance and collective efficacy; with individuals, the interest is on self-efficacy (Bandura, Reference Bandura1982) and individual performance, which is evaluated by the individual him or herself, coworkers, and the experimenter or management.

Taking a small step back in time, beginning with the 1973 petroleum embargo and the oil crisis (Spector, Reference Spector2014), the American economy slowly lost its lead. Wondering how best to manage the declining economy, transactional leadership and Burn's (Reference Burns1978) transforming leadership received attention. In his attempt to put these theories into practice, Iacocca, the chief executive officer of the Chrysler auto company during the 1980s, was successful in saving Chrysler from bankruptcy and it became a profit-maker again (Spector, Reference Spector2014). Iacocca also achieved “high levels of employee morale, and had helped employees generate a sense of meaning in their work” (Spector, Reference Spector2014, p. 366), and he became an icon of how to lead an industry. However, in 1991, another financial crisis brought hardships and ultimately Iacocca was removed from Chrysler's leadership. Even though Anastakis (Reference Anastakis2007) has spoken highly of Iacocca for being a great entrepreneur, scholars claimed that Iacocca did not transform the organizational culture or get employees involved (Spector, Reference Spector2014). With regard to transformational leadership (Bass, Reference Bass1985), scholars asserted that Iacocca, with his appearance of self-sacrifice, was a charismatic rather than a transformational leader.

Transformational leadership originated in Burns's (Reference Burns1978) concept of transforming leadership, which Bass (Reference Bass1985) adopted into his concept of transformational and transactional leadership. Transformational leadership encompasses the dimensions of individual consideration, intellectual stimulation, inspirational motivation, and idealized influence (Avolio & Bass, Reference Avolio and Bass1991, Reference Avolio and Bass2004; Bass, Reference Bass1985). Avolio and Bass (Reference Avolio and Bass1991, Reference Avolio and Bass2004) took this concept to create a model that encompasses a wide array of leadership styles and called it the full-range leadership model; on the continuum spectrum are laissez-faire leadership at one end, transactional leadership in the middle, and transformational leadership at the other end of the spectrum. The Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire, MLQ-5X (Avolio & Bass, Reference Avolio and Bass2004), an instrument to measure leadership style, has been a popular tool (Antonakis, Reference Antonakis, Day and Antonakis2012; Antonakis, Avolio, & Sivasubramaniam, Reference Antonakis, Avolio and Sivasubramaniam2003) that has been applied in research on manufacturing environments (e.g., Gabers, Reference Gabers2016; Mesu & Sanders and van Riemsdijk Reference Mesu, Sanders and van Riemsdijk2015; Uçar, Eren, & Erzengin, Reference Uçar, Eren and Erzengin2012).

Again, economic circumstances played a big role in the manufacturing sector. The great recession took a toll for many companies and businesses in the late 2000s and early 2010s. To keep up with constant changes and still be successful in the automotive industry, Omar, Mears, Kurfess, and Kiggans (Reference Omar, Mears, Kurfess and Kiggans2011) showed through their research working with Renault and Mitsubishi in Born, Belgium, that organizational learning needs to involve the full range of employees and collaboration with other same industry companies, engineers, and academic institutions. The researchers’ influence led Clemson University to found the International Center for Automotive Research (CU-ICAR) that not only provides a comprehensive program that enables successful organizational learning in manufacture work environments but also promotes research in manufacturing education. CU-ICAR was founded in 2007, and today it offers one course in Manufacture Project Management, which includes “Management, leadership, socio-cultural and technical skills training for the successful management of an automotive development or research team” (Clemons University, 2019).

Even though the business sector recuperated from the recession and advanced successfully by applying leadership theories, the U.S. manufacturing industry has faced strong competition over the last few decades because products have been produced more cheaply in some foreign countries. Those remaining manufacturing industries in the U.S. have faced downsizing and/other challenges. U.S. businesses have also become more service-oriented, which had been predicted by Drucker (Reference Drucker2001). A need for a changed management or leadership style in the manufacturing environment arose. Strategies were identified that were needed for desired workflow, customer satisfaction, and worker satisfaction, which suggested the application of transformational leadership. Transformational leadership has the capacity to achieve “best possible organizational performance” (García-Morales, Jiménez-Barrionuevo, & Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez, Reference García-Morales, Jiménez-Barrionuevo and Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez2012, p. 1040; Palmer, Reference Palmer2016). Even though there are studies with encouraging outcomes that can be applied to manufacturing companies (e.g., Fusch & Fusch, Reference Fusch and Fusch2015; Kurtessis, Eisenberger, Ford, Buffardi, Stewart, & Adis, Reference Kurtessis, Eisenberger, Ford, Buffardi, Stewart and Adis2015; Shunlong & Weiming, Reference Shunlong and Weiming2012; Steensma, Reference Steensma2010; Wayne, Shore, & Liden, Reference Wayne, Shore and Liden2017; Woehl, Reference Woehl2011; Yaghoubipoor, Tee, & Ahmed, Reference Yaghoubipoor, Tee and Ahmed2013), the implementation of the transformational leadership style has proven cumbersome. This may be due to applications of leadership theories not complementing product processes well. There seems to be a continued search for a holistic leadership concept that can handle all needs of a production company and also be competitively successful (Baker, Reference Baker2003; Moccia, Reference Moccia2016; Sanders, Reference Sanders2013).

Management-based leadership approaches

During the industrialization of the late 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, companies were operated by owners who exploited workers for the benefit of personal gains (Pearson, Reference Pearson2009). A slight shift away from autocratic leadership (Chiang, Reference Chiang2012; Gastil, Reference Gastil1994; Lewin, Lippitt, & White, Reference Lewin, Lippitt and White1939; Morse & Reimer, Reference Morse and Reimer1956) or authoritarian leadership (Wang & Guan, Reference Wang and Guan2018) began with the founding of the Wharton Business School of the University of Pennsylvania in 1881 (Grachev & Rakitsky, Reference Grachev and Rakitsky2013). Much of its teachings were geared toward motivating employees with the goal to maximize profit, whereby a good relationship with employees was a core tenet.

The era arose in which work efficiency was the primary focus, especially when Taylor (Reference Taylor1911) introduced scientific management in 1903 (Grachev & Rakitsky, Reference Grachev and Rakitsky2013). At first, Taylor addressed in particular engineering managers for efficient shop management. However, he came to disapprove of how workers suffered under the attempts to minimize labor costs, as well as punishment by coworkers if a worker tried to exceed productivity. He sought for a way to be fair to workers while also improving productivity and increasing profits. Studying time spent and details of production workflow, Taylor calculated a piece-rate system with a standard set just below the minimum of attainable production, which was then the production norm for a daily wage. He also laid thereby the foundation of systems thinking, in which workers are an integral part, along with rational analysis, a form of systemic-based science of managing production facilities (Grachev & Rakitsky, Reference Grachev and Rakitsky2013). Taylor, hence, also paved the road for scientific work organizations. Taylorism became a popular trend long into the 20th century.

In the 1950s, however, American industries were shaken up due to manufacturing innovation in Japan. Japanese production was economically struggling (Knouse, Carson, Carson, & Heady, Reference Knouse, Carson, Carson and Heady2009) due to the devastations of World War II. Americans assisted in rebuilding Japan; among those was Deming (Reference Deming1986), who put more attention on product quality rather than quantity. He also believed that everyone in the manufacturing company was responsible for making incremental improvements. His approach brought Toyota its major breakthrough in early 1960s (Knouse et al., Reference Knouse, Carson, Carson and Heady2009). By the 1970s, Japanese cars were of high quality and fuel-efficient, which alarmed the U.S. car industry. Many then took a good look at Deming's principles of quality—later constructed as Deming management model—where one of Deming's principles is to integrate leadership (Anderson, Rungtusanatham, & Schroeder, Reference Anderson, Rungtusanatham and Schroeder1994; Douglas & Fredendall, Reference Douglas and Fredendall2004; Knouse et al., Reference Knouse, Carson, Carson and Heady2009).

Inspired by Deming's continuous improvement approach, Japanese companies developed a model known as Kaizen (Imai, Reference Imai1986). Fundamentally, Kaizen is about efficiency of time management of operation flows (e.g., Carnerud, Jaca, & Bäckström, Reference Carnerud, Jaca and Bäckström2018; Marin-Garcia, Juarez-Tarraga, & Santandreu-Mascarell, Reference Marin-Garcia, Juarez-Tarraga and Santandreu-Mascarell2018). Some U.S. companies have recently implemented Kaizen (e.g., Stahl, Reference Stahl2013), though more in the sense of a production process rather than in today's Japanese companies as a work/life philosophy (Macpherson, Lockhart, Kavan, & Iaquinto, Reference Macpherson, Lockhart, Kavan and Iaquinto2018). For the most part in respect to U.S. management principles, Deming's quality improvement ideology has been associated with total quality management (TQM); however, he was not recognized as the founder of TQM (Martínez-Lorente, Reference Martínez-Lorente1998).

Total quality management was a popular topic in the 1980s and 1990s due to the fact that Japanese production took a strong economic lead, and U.S. companies were trying to figure out how to regain that lead. TQM refers to quality control (Feigenbaum, Reference Feigenbaum1983) needed to produce outstanding products and customer services. TQM is essentially about constantly checking and adjusting strategies and processes to improve effectiveness and productivity to suit customer demands, uphold customer satisfaction, and remain competitive in the business world (Kosicek et al., Reference Kosicek, Soni, Sandbothe and Slack2012; Mallur, Hiregoudar, & Soragaon, Reference Mallur, Hiregoudar and Soragaon2012). Key aspects for successful TQM are top management commitment, employee involvement, customer focus, information technology (IT), improved production planning and control, employee performance recognition system, management vision and mission, and supplier quality management (Aich, Muduli, Onik, & Kim, Reference Aich, Muduli, Onik and Kim2018; Mallur et al., Reference Mallur, Hiregoudar and Soragaon2012; Kothari, Shrimali, & Pradhan, Reference Kothari, Shrimali and Pradhan2017), whereby IT may play the essential role in success in product and productivity for small- and medium-sized companies (Aich et al., Reference Aich, Muduli, Onik and Kim2018). One can recognize that some of the key factors may not have a strong reliance on leadership style, such as production planning and control, recognition system, and IT; it may appear as if manufacturing businesses have further factors to consider besides leadership style and its effects.

Since the 1980s, another management philosophy became popular, leader-member-exchange leadership (LMX) (Dansereau, Graen, & Haga, Reference Dansereau, Graen and Haga1975). Founded on social exchange theory (Thibaut & Kelley, Reference Thibaut and Kelley1959) and equity theory (Adams, Reference Adams1963), LMX has a stronger focus on employees as team members than TQM has. The supervisor forms a working relationship built on trust, and both parties share responsibilities and decision-making (Dansereau, Graen, & Haga, Reference Dansereau, Graen and Haga1975). It was found that workers’ sense of responsibility and duty stand in relation with organizational citizen behavior (Organ, Reference Organ1988, Reference Organ1997); these determine the degree of being dedicated to and reciprocating in ways that favor both their supervisors and the company (Han, Sears, & Zhang, Reference Han, Sears and Zhang2018). Interactions are at the core of LMX, specifically superior–subordinate interactions, and therefore LMX been viewed as a process approach, one that is also represented in transactional leadership. The interactions between superiors and subordinates, the supervisor's expectations, and contingent rewards for jobs performed are all part of transactional leadership (van Breukelen, Schyns, & Le Blanc, Reference van Breukelen, Schyns and Le Blanc2006). However, it has been shown that LMX can also be of benefit with transformational leadership (Shunlong & Weiming, Reference Shunlong and Weiming2012).

Continuing with the historical view of manufacturing in the U.S., much emphasis has been on lean production starting at the beginning of the 21st century (Krafcik, Reference Krafcik1988). The term lean manufacturing was used by Krafcik in his search for high performance in productivity when discussing competitive manufacturing research. In this context, the car manufacturing company Toyota in the 1990s became famous for its production system and world-leading levels of efficiency (Chiarini, Baccarani, & Mascherpa, Reference Chiarini, Baccarani and Mascherpa2018); its U.S. car sales had resulting successes. Even though there has not been a consensus on the definition of lean production (Pettersen, Reference Pettersen2009), the general understanding of lean manufacturing is simplifying and standardizing work procedures to achieve high quality and productivity by reducing or even eliminating waste in production time and cost (Mehta & Shah, Reference Mehta and Shah2005). Because lean manufacturing might not be possible in some cases, company leaders began looking at types of teamwork and employee issues in order to increase production. A way to compensate for this has been to integrate LMX (Dansereau et al., Reference Dansereau, Graen and Haga1975) because this approach takes employees into consideration as members of a team.

The most current approach to work performance and efficiency as well as product quality in the manufacturing industry is Six Sigma. Six Sigma is based on the use of statistical methods to calculate variation in processing; one then reduces variations in processing to arrive at improved operation and capacity, as well as lower operation costs (Murumkar & Teli, Reference Murumkar and Teli2019). Six Sigma arose from the TQM approach, specifically with the aim of continuous improvement. Lean Six Sigma combines the framework from lean manufacturing, making use of reduction of waste, defects, and process variations and the outcomes of increased quality, cost effectiveness, and customer satisfaction (Albliwi, Antony, & Lim, Reference Albliwi, Antony and Lim2015).

Six Sigma and lean manufacturing, despite their advanced applications of technology and customer focus, are still production process approaches and are set relatively equivalent to TQM. As product process approaches, they are in need of management philosophies or leadership paradigms to complete overall organizational progress and sustainability (Moccia, Reference Moccia2016; Sanders, Reference Sanders2013). There has been ambiguity due to difficulties in translating theory into practice, especially in regard to a clear approach to TQM, and its relation “with the bottom line” (Soltani, Lai, Javadeen, & Gholipour, Reference Soltani, Lai, Javadeen and Gholipour2008). In addition, due to high competitiveness with cheaper production and sales of goods in the global market, it appears the first focus of quality management in manufacturing today is centered on technology and customer satisfaction, even when discussing creativity (Zimon, Reference Zimon2015). The component of human-resources management within quality management appears to have taken a relatively low priority. It seems still much the case in regard to “human resource focus … [that] the empirical literature is silent with respect to any new or overlooked aspects” (Baker, Reference Baker2003, pp. 170, 175). Taking an employee-centered orientation has occurred mostly in relation to work place health (e.g., Anger, Reference Anger2015; Geldart, Smith, Shannon, & Lohfeld, Reference Geldart, Smith, Shannon and Lohfeld2010; Rampasso, Anholon, Gonçalves Quelhas, & Filho, Reference Rampasso, Anholon, Gonçalves Quelhas and Filho2017; Wang, Liu, Yu, Wu, Chang, & Wang, Reference Wang, Liu, Yu, Wu, Chang and Wang2017; Zoller, Reference Zoller2004) and safety culture (e.g., Abellon & Wilder, Reference Abellon and Wilder2014; Beus, Reference Beus2010; Burke, Sarpy, Tesluk, & Smith-Crowe, Reference Burke, Sarpy, Tesluk and Smith-Crowe2002; Ghahramani & Khalkhali, Reference Ghahramani and Khalkhali2015; Lundell & Marcham, Reference Lundell and Marcham2018; Oliver, Cheyne, Tomas, & Cox, Reference Oliver, Cheyne, Tomas and Cox2002). In establishing a safety culture, Lundell and Marcham (Reference Lundell and Marcham2018) state that transformational leadership may be most effective.

There may be a need for a refreshed view of the human side (McGregor, Reference McGregor1960; Moccia, Reference Moccia2016) in manufacturing, and it appears there is a search by manufacturing companies for a solution that is all inclusive, perhaps a multidisciplinary approach (Wilson, Reference Wilson1998; see also Johannessen, Olsen, & Olaisen, Reference Johannessen, Olsen and Olaisen2005). In the search for a holistic management philosophy, Gutierrez-Gutierrez, Barrales-Molina, and Hale (Reference Gutierrez, Barrales-Molina and Hale2018) worked toward a framework that unites knowledge from various disciplines in order to merge approaches, with particular consideration of human resources quality management in regard to new product development. Their model outlines that training, empowerment, and teamwork constitute the foundation of HR-related quality management practices; these establish the foundation of learning orientation and knowledge integration, where both combined with strategic flexibility lead to new product development. They stress the importance of organizational learning (Argote, Reference Argote2011; Argyris, Reference Argyris2004; Schön & Argyris, Reference Schön and Argyris1978, Reference Schön and Argyris1996) for a company's innovation potential and progress. This and others’ search for a holistic management philosophy may be the reason, or is recommendable for production companies to integrate transformational leadership as the “soft factor” and means to success into a holistic quality management approach (Moccia, Reference Moccia2016, p. 229).

The numbers in the literature say a lot

When typing in a general search in an online library that has 52 databases, the numbers can provide some insights. The search with “manufactur” (entailing both “manufacture” and “manufacturing”) returned 175,024 results and “manufactur AND leadership” 7,017 results in journal articles, books, dissertations, reports, newspapers, and a few blogs, including articles in foreign languages. The search with “production-line” returned 506,755 results (mostly on strategies dealing with, for instance, reduction of waste). These huge numbers (175,024 pertaining to manufacturing and 506,755 pertaining to production-line) show there is an enormous interest in the subject of manufacturing. A closer look reveals that most literature is in the form of books.

Reducing the search to only journal articles, “production line” returned 28,702 results. The search of “production line” in psychology-related journals returned only 414 results, though not all articles have the focus on manufacturing/production-line workers; of the 414 results, 284 pertained to “production line AND transformational leadership.” This shows that there is an increasing interest in transformational leadership in manufacturing research and/or companies. The sources from which many articles could be retrieved were from the Journal of Applied Psychology, Journal of Managerial Psychology, and, astonishingly, from the Applied Ergonomics journal.

When viewing the sources of journal articles on transformational leadership pertaining to manufacturing environments, some were associated with engineering. Therefore, a search in databases of engineering was conducted. It was found that the Journal of Cleaner Production had the most articles referring to leadership; the majority of articles were published within the last two years. Other journals in which one finds a few articles on leadership are Engineering Management Journal (returned 13 results), Journal of Management in Engineering (returned 11 results), Leadership and Management (returned two results). Other journals were retrieved, such Journal of Applied Mechanical Engineering, Global Journal of Engineering Science and Research Management, and International Journal of Project Management and Safety Science; however, these articles were not accessible without membership to those journals. The numbers indicate engineers’ growing interest in leadership topics, particularly in transformational leadership, even though leadership goes beyond engineers’ training and field of expertise. Engineers are gradually taking on more leadership roles (Perry, Hunter, Currall, & Frauenheim, Reference Perry, Hunter, Currall and Frauenheim2017), and more engineers are publishing on leadership in engineering-related journals. Engineers see themselves compelled to do this because “… global mobility and competition resulting from increasingly transnational economies demand that North American engineers lead cross-cultural, inter-disciplinary teams and respond to a range of stakeholder concerns [and] merging technical and humanistic aspects of engineering is rooted in the idea of professional service” (Rottmann, Sacks, & Reeve, Reference Rottmann, Sacks and Reeve2015, p. 3). The thought comes to mind that the manufacturing sector has circled back to the times of scientific management (Grachev & Rakitsky, Reference Grachev and Rakitsky2013) that took place in the early 20th century. Perhaps a new Taylorism (Taylor, Reference Taylor1911) mentality is needed for those trained in psychology, particularly I-O psychologists.

Conclusion and recommendation

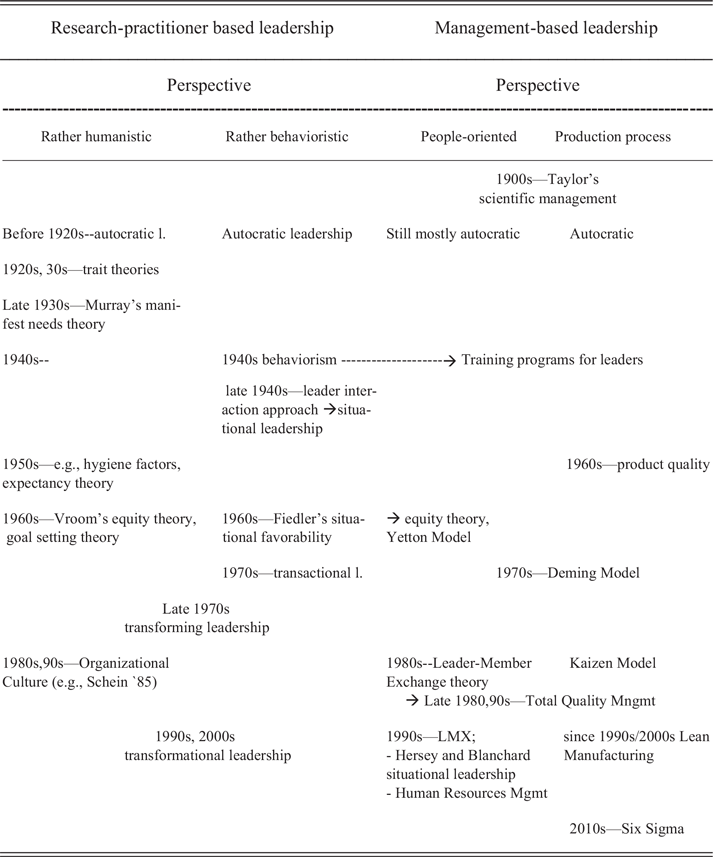

This literature review provided a general overview of the history and development of leading U.S. manufacturing companies becoming successful because psychological concepts were applied. The timetable of leadership theories adopted into U.S. manufacturing companies shows that many leadership studies were conducted in and applied to manufacturing environments up to the 1970s, followed by decades of transactional leadership having some impact as leadership style (see Table 1). Transformational leadership has made a slow entrance into manufacturing environments, but as a separate focus rather than as an integrated part of a whole manufacturing system. This timetable of leadership theories’ arising and being implemented into manufacturing environments corresponds with Burke's (Reference Burke2018) writing of the evolution of psychological organizational development. Burke explained that organizational development reflected economic events, especially economic growth, and then stagnated since the 1970s. Beginning with the 1990s and especially starting with the time of the recession around 2008, I-O psychologists followed the economic trend and geared strongly to the service-oriented market. This has contributed to a shift in interest of I-O psychologists to focus on the business sector and to neglect the manufacturing sector. In addition, many larger manufacturing companies have moved facilities to foreign countries. Most small- and medium-sized manufacturing companies are trying to survive the highly competitive economy and get by with the necessary leadership investment while focusing on productivity, workplace safety, and other requirements, such as those determined by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). They seem to not have resources to try to improve by applying insights from I-O psychology.

Table 1. Time Line of Leadership Theory Applied to U.S. Manufacturing

The manufacturing sector has been deserted by I-O psychologists and left to those with strong production process-oriented leadership; these have been the Kaizen model since the late 1980s, lean manufacturing with start up in the 1990s, and Six Sigma since the 2010s. Recently Balzer, Brodke, Kluse, and Zickar (Reference Balzer, Brodke, Kluse and Zickar2019) addressed this departure from manufacturing by stating, “… the industrial and occupational (I-O) psychology community has largely ignored the Lean research literature as well as ceded applied work in Lean to other organizational practitioners” (p. 215). They further write: “There is a dearth of evidence-based research by the field on the psychosocial aspects of Lean that would enrich the understanding of Lean, whether and why it works, and how best to implement it” (p. 216). This backs up some of the outcomes of this literature review and concluding claims.

Balzer et al. (Reference Balzer, Brodke, Kluse and Zickar2019) conducted a thorough literature search and review for I-O psychology content pertaining to Lean. Similar to our literature search, I-O psychology research has been extremely scarce. Balzer et al. also offer some possible explanations why I-O psychologists have ignored Lean. One explanation, and perhaps excuse, is that Lean may have been viewed as a fad, a transitional style, and not worth showing interest in. As another major deterrent, the researchers believe that Lean research does not reach the standard of I-O psychology and thus has not been included in I-O psychology journals; therefor, there is a lack of information on Lean among I-O psychology academicians, researchers, and practitioners. In regard to leadership, Balzer et al. state there is a need to study the relationship between leadership theories and practices as well as leadership and organizational effectiveness. We agree with their recommendation and add that there is a need to seek a holistic leadership approach that embraces all facets of a company. This echoes Gestalt theory, where all entities work together as one system; not one of the entities can be neglected, otherwise the whole system does not function smoothly.

Another article that supports our claim recently has been published. Burke (Reference Burke2018) writes about the rise and fall of organizational development (OD), hence a very closely related theme as this article, addressing more I-O psychology practitioners. As one of the reasons for the fall of OD, Burke asserts that corporations are not driven by their own mission but by strategy, and then states it would be “best to beat if not destroy the competition” (Reference Burke2018, p. 196). This can be agreed upon; companies need to check frequently that all entities of the company align with the corporation's mission. With pressures to focus on production, some facets of the system may be neglected, causing disturbances in the long run. However, we disagree with Burke's recommendation “to beat if not destroy the competition.” The opposite appears more applicable. Just as teamwork within the company is beneficial, collaboration outside the company makes it strong, too. Hence, having a community orientation strengthens the company. For instance, companies become competitive in the sense of being economically robust; plus, being socially responsible elicits good reputation for the company, which in itself promotes the products or at least heightens desire to work for the company. Community-orientation may be a way of taking Burke's recommendation of “expanding their client base beyond the usual suspects—business-industry corporations” (Reference Burke2018, p. 196). With this kind of mindset, we recommend that I-O psychologists and students should work in collaboration with other education and training programs, professionals, and manufacturing companies. I-O psychology graduate students can complete internships in manufacturing environments to get an understanding of processes, work flows, influences of leadership, organizational culture and climate, exposure to environmental stressors, work languages, working with people of different population groups, and the gaps between production and administration, as well as production and organizational decision-making. Or students can complete internships with business consultants who are not trained in I-O psychology but advise, coach, and train on manufacturing matters based on their expertise or gained insights from working with manufacturing-related professionals. University professors can shadow manufacturing managers over the summer term and/or take a sabbatical to work part-time and conduct observations for the rest of the work days; these observations may lead to insights that would otherwise remain masked. I-O psychology practitioners and consultants can visit with consultants outside of the field to share insights or perhaps temporarily exchange jobs; they could have weekly meetings with article readings and discussions from journals of different professional fields. Overall, they can start forming collaborations with other professionals who work within or for manufacturing companies, gain as much insight as possible, and share those insights then with I-O psychology colleagues, practitioners, students, and conference participants.

I-O psychologists may be familiar with TQM and lean approaches, but they most likely do not know about manufacturing-related aspects, such as Kaizen. One must have a fundamental understanding of management and operation concepts of manufacturing environments to be able to assist with leadership concepts in manufacturing companies. To achieve this, colleges need to provide this foundation. Currently if a student wants to specialize in providing service to manufacturing companies, he or she would have to complete courses from business and engineering programs in addition to his or her I-O psychology program courses. Also, graduate I-O psychology programs generally offer courses that contain research–practitioner-based leadership approaches. What is needed are I-O psychology programs, perhaps also organizational management and similar programs, to integrate management-based leadership approaches so students have a foundation to understand people and product processes in manufacturing environments.

Burke (Reference Burke2018) also calls for “a voice for the field” (p. 203). We are planning to present excerpts from this practice forum at the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology (SIOP) conference in April 2020; this will include a think-tank activity to gather ideas from educators and practitioners regarding how to provide I-O psychologists with the means to be supportive to manufacturing companies. Guiding questions may be as follows: What is needed to provide graduate students with the knowledge/training to understand manufacturing operations, processes, and tangibles? What is needed to get graduate students and practitioners prepared to face the challenges manufacturing companies are confronted with? What is needed or what service can be offered (and by whom) so practitioners are equipped to provide quality services to manufacturing companies? How can one stimulate an increase in research pertaining to manufacturing environments? The outcome of the ideas and suggestions will be put together and shared with a SIOP forum or submitted for publication to reach a large readership. The goal is to adjust curricula, training, or services that are geared toward supporting manufacturing, particularly to small- and medium-sized manufacturing companies.

If more I-O psychologists and programs generate psychological knowledge and implementation strategies geared to manufacturing environments, perhaps more small- and medium-sized manufacturing businesses will arise, possibly making America a leading manufacturer power worldwide again. One may also consider the current politics and discussions regarding bringing manufacturing back to the U.S. Now is a good time to summon I-O psychologists to provide services and road maps for leadership that fit into a holistic concept of manufacturing environments.