On March 13, 1963, the Australian Women's Weekly published a Letter Box submission entitled “Teacher Objected to Muu-Muu.”Footnote 1 Letter Box was constructed as a space for readers of the Weekly to share their observations and concerns, but contributions were generally not in response to the editorial content of the magazine; instead, they focused on aspects of individuals’ own lived experiences. The Weekly had, from its inception in 1933, encouraged submissions from readers. As the premier issue had declared: “The womenfolk of Australia are invited to regard this paper as their own exclusive medium, through which they may express their ideas and thoughts—critical, constructive, humorous, and otherwise.”Footnote 2 Through both their submissions and their subscriptions, Australian women took up the call.Footnote 3

By the late 1940s, the magazine was reaching more than one in three households in the country,Footnote 4 and it remained tremendously popular during the decades that followed, boasting the largest per capita circulation of any women's magazine in the world.Footnote 5 It was therefore a given that any contribution to the Weekly was widely read.

Some letters, however, received attention that went above and beyond the norm. “Teacher Objected to Muu-Muu” was one of these. It went as follows:

During a hot stretch of Queensland summer, with a forecast temperature of 92 degrees, I sent my little eight-year-old girl to school dressed in a neat spotted and fringed muu-muu. Her teacher, in front of a class of 57, quickly took her to task, saying that a Grade 5 girl should have more sense than to wear a muu-muu to school. But isn't it a more sensible type of clothing for the climate?Footnote 6

After her daughter was reprimanded about the spotted (polka-dot) muumuu, this mother was not content to confer with the teacher about standards of appropriate school dress. Rather, she asked for advice from a larger group of fellow women, not simply by chatting at the school gate, but by submitting a letter to the nation's most popular magazine. Her letter struck such a chord with readers that many submitted responses. A sampling, representing a range of opinions, appeared in one of the following issues, with the heading “School Muu-Muu.” A teacher voiced her disapproval of the letter writer, saying that she “would censure any child in [her] class who came to school in questionably fashionable dress.” Other readers agreed, asserting variously that “discipline must be adhered to and no exception made for ‘Mother's special little girl,’” and “school uniforms are out of place at the beach and muu-muus likewise have their own time and place.” But just as many sided with the original writer, calling the teacher in question “old-fashioned” or implying that she was cruel. One mother admitted that during heat waves she had been “tempted to send [her] children to school in muu-muus but [had] been deterred at the thought of the teacher's remarks.” She offered what she saw as a “most practical solution”: “a modified muu-muu-type uniform in a cool color or stripe.”Footnote 7

At the time these letters were written in the early 1960s, many Australian publicFootnote 8 schools lacked mandatory or detailed dress codes.Footnote 9 But schoolchildren's dress did not go entirely unregulated. In Queensland, for example, regulations dating back to the late nineteenth century stipulated that “children must come to school respectably clothed and clean.”Footnote 10 On the surface, this was a simple prescription. And yet it pointed to codes of respectability, however obscure or unelaborated, that had to be observed. When the Queensland mother described her daughter's muumuu as “neat,” she called to mind a tidy house, a well-ordered house; when she used the word “sensible,” she conveyed prudence and propriety. In asking her question about the muumuu, this mother was working to negotiate the values that words such as these communicated.

Taking up these matters of mothering, appropriate clothing, and mass-market magazines, we advance three connected arguments in this paper. First, we assert that over the course of the middle decades of the twentieth century, the Australian Women's Weekly contributed to the development of the uniformed schoolchild as a cultural trope by increasingly representing young people as properly dressed for school only if they wore “regulation” or mandated clothing. Related to this, we note that the Weekly’s coverage over this period increasingly depicted generically uniformed children—differentiated by gender and age—rather than drawing attention to the distinctions between different uniforms for different schools.

Our second argument ties the trope of the properly dressed schoolchild to associated representations of the school mother working to produce or procure the school uniform and to arrange and manage the uniformed child. We contend that the magazine portrayed this work as part of a project to draw the mother into a respectable and ostensibly “Australian” community.

The third argument is about understanding mass-market women's magazines as a significant historical source on matters of schooling. Mass-market magazines in general, and the Australian Women's Weekly in particular, have been quite extensively used in social and cultural histories but scarcely employed in Australian histories of education. In this paper, we identify various meanings (rectitude, practicality, modernness, egalitarianism) that a social and cultural agent outside the school historically attached to the school uniform. We seek to document how this agent—the Australian Women's Weekly—assembled, mediated, and exchanged ideas about the normative school mother and child.

Our emphasis is thus not on disciplinary practices or policy-making, but rather on the cultural reification of the uniformed bodyFootnote 11 as a recognizable representation of the schoolchild, schooling in general, and the practice of mothering, inasmuch as the mother was represented, directly and indirectly, as effortfully and purposefully clothing the child for school. Before we discuss the use and value of the Weekly, we first turn to a brief history of uniforms in Australia and a survey of the international literature on the history of school dress in order to background the paper in a specific Australian history of school clothing and to clarify the meaning of the key term school uniform.

Daphne Meadmore and Colin Symes note that in Australia “uniforms were not uniformly introduced into schools; rather, their introduction occurred in a piecemeal way, garment by garment.”Footnote 12 This began during the late nineteenth century when some private schools and public secondary schools, seeking to convey their identity and exclusivity, instituted requirements that students wear sets of clothing modeled on those found in comparable British schools. By the 1930s, designs had converged into some typical forms. Basic elements were collared shirts, ties, blazers, and V-neck pullovers. Shoes came in black or brown leather, and hats included wool caps, straw boaters, and rounded Panamas. Girls often wore pleated, sleeveless tunic dresses over blouses, and boys wore shorts or long trousers, depending on their age and the time of year. A restricted palette of colors applied, largely featuring white, gray, blue, tan or brown, black, green, and/or red. Patterns commonly consisted of straight lines in the form of stripes, checks, tartans, or plaids (spots, or polka dots, were not seen).

Despite this trend, the proliferation of uniforms by midcentury was quite limited, for generally speaking, public primary schools had not followed suit (and secondary schooling was still in the process of becoming universal). The clothing worn by children attending their local public school at this time typically did not match. Hats were not widespread and, notwithstanding the existence of leather “school shoes” (the footwear marketed as appropriate for school), it was not uncommon through the 1950s for children to go to school barefoot, especially in warmer areas, and especially if they were not wealthy.

Only by the 1980s and 1990s did school uniforms become overwhelmingly adopted and worn across Australia in every type of school. Styles varied: many institutions brought in items such as sweatshirts, polo shirts, and sunhats; others retained or instituted more traditional items, such as blazers, ties, and boaters. Nonetheless, by century's end, in the vast majority of schools across the country, students now dressed in the same prescribed garments as their fellow classmates.

Jennifer Craik identifies three main national school uniform traditions: the British Public school style (influential in former British colonies like Australia), a more explicit military dress (seen, for example, in Japan), and the ecclesiastical/hygienic smock (Argentina).Footnote 13 Some countries, such as Korea, have histories of nationally identical uniforms,Footnote 14 whereas in countries such as Australia and Britain, uniforms have been used to distinguish between schools, especially at the secondary school level.Footnote 15 The US has traditionally been an exemplary nonuniform nation, but since the 1980s has witnessed a marked growth in the adoption of dress codes and uniform policies.Footnote 16 Defining the terms, Brian McVeigh proposes a semi porous boundary line between a dress code and a uniform that relies on the degree of explicit external regulation and codification: dress codes specify what may or may not be worn, whereas uniform codes insist on what must be worn.Footnote 17

Internationally, the scholarly literature of school uniform history is sparse, thinly spread across the history of education and the history of clothing. There are, however, some shared points of interest, notably in the gendered social relations embedded in uniforms. For example, some of the literature notes a masculinist lineage of uniforms, descended from military attire and physical training.Footnote 18 Historians of girls’ schooling have remarked on the function of uniforms in implementing a girls’ curriculum of docility and self-effacement, sometimes at odds with the lessons in other areas of school life.Footnote 19 Uniforms can also be viewed through the lens of student resistance, notably in the context of postwar girls’ teen culture.Footnote 20 This paper is a cultural history, examining school uniforms in popular representation. In paying particular attention to the visual and tactile, we share some ground with the growing body of work in the history of education on images and materialities.Footnote 21 Some of the most interesting analysis of school uniforms in this field comes from Inés Dussel, who has written extensively about the white smock introduced about 1910 into Argentine public schools. The smock became nationally iconic, wrapped up, as she notes, in discourses of hygiene, morality, egalitarianism, and thrift.Footnote 22 Dussel writes that she has been “confronted with … arguments about the triviality of [school uniforms]. … Don't we have more pressing things to be concerned about? Isn't it frivolous to talk about clothes when schools are faced with enormous challenges?” Dussel answers her own question by arguing that uniforms are an important element of the cultural history of schooling, and also that “the life of schools is made of many of these ‘inconsequential things’ that have far more influence on the way teachers and students perceive themselves and relate to others than might be presumed by the space given to them by educational research.”Footnote 23

In this spirit, we argue that apparent inconsequentiality—a description that could apply equally to school uniforms and women's magazines—can mask real cultural power. Writing in the 1970s, Elaine Thompson claimed, “The Australian Women's Weekly generates a picture of the world, of women, of society, which is projected week after week to a huge part of the Australian population.”Footnote 24 This magazine is not just a useful historical source of illustrative content—one of any number of publications that we could have chosen to study—but has its own substantial historical significance as a social and cultural agent.Footnote 25 The Australian Women's Weekly, for many decades the best-selling periodical in the country, served as a formidable authority, trading particularly in the routine and the domestic. Significantly, and unlike many women's magazines in other countries, the Weekly was widely read not only by women but also men,Footnote 26 albeit generally purchased by women. At the risk of oversimplifying this rich and complex historical source, the “Australian woman” conventionally represented by the magazine's writers and illustrators during its first fifty years was a current or future “housewife” and mother with an almost universal set of core characteristics, including whiteness, heterosexuality, and native English-speaking—as Susan Sheridan points out in her standard history of the magazine.Footnote 27 This was reinforced by the regular inclusion of stories or correspondence from or about those who were outside such bounds, including “migrants,” Aboriginal people, and—in different ways—Hollywood movie stars and the British royal family.Footnote 28 The school uniform content was consistent with this normative presentation and with the magazine's didactic house style.

One of our aims in this paper is to explore an aspect of the labor and identity of the twentieth-century housewife-mother that has hitherto been relatively little remarked upon in the literature—her school-related labor. In doing so, we build on some previous work in which we examined the Weekly's dissemination of advice about how mothers should support their children's schooling (preparing healthy school lunches, washing clothes, reading aloud, physchological nurture), arguing that schools comprise an important, yet under recognized, site for the making of twentieth-century motherhood.Footnote 29

In advancing this feminist analysis, we note that Australian school uniforms were conventionally differentiated by gender in appearance and purpose, as others have pointed out and as our investigation of the Weekly demonstrates (even though not necessarily more differentiated than other clothing for young people). This is certainly an important element of any study of uniforms. Our main contribution to a gendered reading of uniforms, however, is to consider their significance as representations of maternal competence. In common with Dussel, we find uniforms to be significant in their ubiquity, but in this paper we focus our attention not on the child in the school so much as the child in the family or the child in public—and indeed the imagined or ideal child, produced and managed by her mother.

Content about school uniforms appeared frequently and regularly in the Australian Women's Weekly, with particular intensity in January and February at the beginning of each school year. An interest in what children and young people wore to school can be seen as part of the magazine's ongoing engagement with its putative readership: married women who were mothers and who bore the main responsibility for the smooth running of their households. The muumuu letters described above were part of a larger “debate” about the utility and worth of school uniforms conducted through the magazine's pages from its foundation in the 1930s until the early 1980s.Footnote 30

For the research project upon which this paper is based, we identified and tracked the Weekly's coverage of uniforms through systematically collecting and reading its copy across a full range of content, both text and images, including covers, editorials, advertisements, expert advice, letters, fiction, sewing patterns, and cartoons. In particular, we note the significance of advertising copy in the effective resolution by the late 1970ss of the Weekly's manufactured debate on school uniforms in favor of the uniformed child. This paper offers a cultural account of the adoption of uniforms as standard practice in Australian schools during the middle decades of the twentieth century.

“Sloppy Sue Is Taboo”: Origins of a “Debate” about School Uniforms

From its beginnings in the early 1930s, the Weekly featured content on school wear. There were “back-to-school” advertisements for “Regulation Tunics” and ties “in all required school colours.”Footnote 31 The “Fashion Service” section offered mail-order sewing patterns for items such as “the correct style” for a school blazer (see Figures 1 and 2).Footnote 32 The language of these advertisements emphasized a need for compliance and exactitude when outfitting children for school. The message was that proper school dress was a matter of conformity—of uniformity. More than this, the message was that the uniform-wearing schoolchild was the “correct” schoolchild, and this was nearly always visibly gendered, even where the items, such as the girls’ and boys’ blazers in Figures 1 and 2, looked very similar.

Figures 1 and 2. Idealized schoolchildren in advertisements for sewing patterns. (Australian Women's Weekly, Aug. 12, 1933, 31, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page4604621; and June 13, 1936, 58, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page4614041.)

Whether despite or because of such messages, opinions on school uniforms began to appear in readers’ letters within the magazine's first few years of publication. A woman from Sydney observed:

News comes from London that mothers are objecting to the use of standardised school uniforms for schoolgirls on the grounds that the uniforms are ugly and lead to unnecessary expense. As a result many important girls’ schools are relaxing their regulations regarding dress.

In Australia, almost all the important private and many of the public girls’ schools make the wearing of a standard uniform compulsory. Is this really necessary? Should not each girl have an opportunity of developing her individuality even during school years?Footnote 33

A woman from Queensland took the opposite view:

To my mind, one of the needed reforms is a compulsory uniform for State school girls. Secondary schools and colleges have a regulation uniform, so why not a State school uniform? … When I think of the many ill-clad State school girls there are, not through lack of money but through lack of taste, I think the time has come to make a State school uniform a compulsory matter.Footnote 34

This was the effective beginning of what would eventually become a perennial back-and-forth about school uniforms. The magazine would come to frame opinions on school dress in debate terms—“for and against”—and describe the topic as “evergreen” for its enduring nature. Many points would be made along the way, but in this initial exchange some of the basic themes were already present: On the one hand, there was a complaint about the appearance of uniforms, an objection to their cost, a preference for fewer rules regarding school dress, and a concern about whether uniforms might prevent students, especially girls, from expressing their individuality; on the other hand, there was a belief that school uniforms represented a trend that should be more widely followed, a preference for the look of uniforms, and a feeling that many people lacked good judgment when it came to choosing appropriate attire for school. Significantly, the illustrative examples called up by correspondents were usually female: the young or maturing bodies of girls and the guidance and labor of mothers made up a significant element of the uniform “debate” throughout the decades.

To substantiate her views, the letter writer from Sydney referred to “news” coming from London. Britain was the source of Australia's school uniform archetypes, and it continued to exert a strong influence.Footnote 35 The United States, on the other hand, was a place of modernity and teen culture, both desirable and alarming. When it came to school dress, the Weekly framed the United States as a place where students wore “what they pleased.” A 1944 article, “U.S. Dress Designers Fight ‘Sloppy Sue’ Craze,” served as a cautionary tale. The subtitle—“Campaign to Wean Schoolgirls from Current Cult of Untidiness”—alluded to the problem. The piece opened with the premise that “American schools do not use school uniforms.” Rather than encouraging girls’ “interest in clothes,” which the article implied would have been a different and salutary outcome, the lack of regulation had instead led to shows of nonchalance, such as unpolished shoes, shapeless sweaters and skirts, and messy hair. The article was accompanied by photographs of American students that documented various examples: There were high school girls wearing the large (unaltered) jackets of boys who had gone off to war. There was a crowd of young women in oversized sweaters, some with rolled-up sleeves for “an extra touch of anti-glamor.” There were schoolgirls whose penchant for “odd dressing” had resulted in wearing knee pants, not to mention the occasional bow tie, and there were others who wore men's shirts untucked over rolled-up jeans. Instead of wearing traditionally feminine clothing tailored to their bodies, these “young misses” were flouting gendered norms of dress, opting for menswear with bulky and/or shortened silhouettes, or, in cases in which an item was meant for females, obscuring the “shape” by wearing it “several sizes too large.” Clothes manufacturers had reportedly responded to this trend with “horror” and were rolling out a national campaign bearing the slogan “Sloppy Sue Is Taboo.”Footnote 36

The Weekly compared the situation in America with that in Australia in a section sub headed, “Neatness Is Preferred Here.” It began by noting that “school uniforms, though not compulsory with rationing difficulties, are still worn by most High School girls.” The “headmistress of a large girls’ school” was cited as making the point that “the wearing of uniforms had precluded any development of such a cult as the ‘Sloppy Sue.’” Elaborating, she allowed that there were nonetheless “small fashion trends”: “Some would manage to tilt their hats, however conservative in style.”Footnote 37 But it seemed the loose state of school dress in the US had, for the time being, answered any observations that some of the “important schools” in the UK had relaxed their dress requirements. The message was that, if there was scope for “individuality” in Australia, as the letter writer from Sydney had put it, it should be limited to the tilt of one's Panama.

The Sara Quads Go to School

Children appeared regularly in the pages of the Weekly during the 1930s and 1940s, not only in advertisements for clothing, food, medicine, and other household items, but also in articles on topics such as health and parenting. But in addition to this, the Weekly showed other children—not children in the abstract, not the unnamed tykes in drawings, paintings, and photographs whose purpose was illustrative, nor those referred to generally in the magazine's copy, but rather specific, actual children whose noteworthy status derived from their very birth.

There were, for example, the Dionne Quintuplets of Canada (five identical sisters who were the world's first known surviving quintuplets), the Johnston Quadruplets, and the Miles Quadruplets (respectively, the first known surviving quadruplets in New Zealand and the UK). Born from 1934 to 1936, these “three famous baby families” came across visually as symbols of abundance during a time of scarcity. By juxtaposing photographs, the Weekly went so far as to parade them all together in the 1936 feature “Our Baby Show of Quads & Quins.”Footnote 38

In August of 1950, Australia witnessed its own multiple-birth phenomenon. Over the space of a few days in the coastal town of Bellingen, New South Wales, Betty Sara gave birth to two girls and two boys: Alison, Judith, Mark, and Phillip. Frank Packer, owner of the Consolidated Press, the publisher of the Weekly, sent a team of people to negotiate an exclusive sixteen-year contract with the Saras. Betty would prove to be a bonus for the Consolidated Press. London-born, she had always been told how much she resembled Princess Elizabeth.Footnote 39 She even had a variant of her name. It was as if Elizabeth was simultaneously living an alternate antipodean life as a middle-class housewife with new baby quadruplets (and a four-year-old to boot). And she had just signed a deal with the Weekly.

The year 1950 marked more than a new decade—the last wartime rationing in Australia had ended just weeks before the Sara quadruplets were born.Footnote 40 Previous to this, the magazine had operated during periods of depression, war, and austerity. Political content and war coverage had become central to the publication.Footnote 41 But a new editor, Esmé Fenston, had taken charge of the magazine in June, and she was helping to shift the publication toward more lighthearted features focused on prosperity, domesticity, and celebrity.Footnote 42 In the Sara family, all three of these elements came together. The Saras—white, Anglo, suburban, industrious, productive—seemed to personify the ideal Weekly family. The quads themselves—numerous and thriving—were ready-made symbols of modern Australian childhood. The magazine would oversee and disseminate every image and every story about these children, as well as every advertisement featuring them. The plan was that every issue featuring the quadruplets would be a bestseller.Footnote 43 Every time they appeared in the Weekly, they would do so not as anonymously rendered children but as celebrity children—Australia's children—imputing a powerful desirability to any consumer item, child-rearing technique, or quotidian activity featured on the page and, explicitly or implicitly, valorizing the mother ostensibly making the choices.

In the first feature about the family, the Sara quadruplets’ mother was quoted on how she intended to raise the children:

Betty Sara is planning already how she will dress them when they are running round.

“I like little girls in crisp gingham frocks in summer and tailored coats with velvet collars in winter. … I think little boys look nicest in tailored pants and blue or white shirts.”

If the Sara family follows its present intention of remaining in Bellingen the children will start school at the Bellingen State School.

The boys will then go on to their father's old school, Sydney Grammar. Mrs. Sara fancies a grammar school for the girls when they are older.Footnote 44

This conversation was reported as having taken place three days after the birth of the last quadruplet, when the babies and their mother were still in the hospital. Yet the article did not suggest that matters of health and recovery were foremost on Betty's mind. Instead, it had her dispensing opinions on tailored children's clothing and preferences for schools. The piece acknowledged that when it came time, the four children would probably first attend the local state school. In this case, that was Bellingen Central School, which, in addition to the primary years, offered a partial secondary education, culminating with the Intermediate Certificate. The minimum school-leaving age in New South Wales was fifteen at the time, and the Bellingen school provided students with the full education required by the state. But that did not suffice in the pages of the Weekly, at least not when it came to providing a sense of the future prospects of Australia's first quadruplets. The magazine made it clear that the family would need to relocate at some point in order to give the children a “grammar school” education.Footnote 45 The Weekly used the fact that Percy Sara had attended the prestigious Sydney Grammar School as the basis for indicating that the children would go on to such schools as well, giving the impression of a family legacy of educational privilege. Even at this brand-new stage of the quadruplets’ life, the magazine was portraying them in such a way as to compel readers’ aspirations for their own children.

Not surprisingly, advertisers did the same thing with the Sara siblings. A January 1952 full-page advertisement for Paddle children's shoes made it known that “The Sara Quads Are Wearing Paddle Shoes! Mrs. Sara, like most mothers, knows what's best for her babies. And in shoes, it's Paddle!”Footnote 46 When this ran in the Weekly, the quadruplets were seventeen months old. The Paddle illustration did indeed feature two boys and two girls who all fairly resembled one another and did not look unlike the Saras. These children, however, were well beyond their toddler years. They were meant to sell “school shoes,” the sensible leather children's shoes marketed in Australia at this back-to-school time of year. In the scene, the two boys are playing cricket and the two girls are spectating (see Figure 3). They are dressed to match but also to be distinguished by their gender. The boys are wearing gray shorts, white-collared shirts, and long gray socks with two red stripes. The girls are wearing gray, pleated tunic dresses atop light-green collared shirts. This scene takes place outside a school. It was clearly not purporting to be an actual image of the Sara quads—the very ad copy mentioned they were “babies.” Nonetheless, it conveyed a future for them. The implication was that they would eventually find themselves at school with students dressed uniformly in plain collared shirts, other items, and Paddle school shoes.

Figure 3. This 1952 advertisement featured fun-loving children wearing school uniforms. (Australian Women's Weekly, Jan. 23, 1952, 4, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page4387789.)

As previously anticipated, the young Saras started school in the small town where they were born. A July 1955 Weekly cover shows them standing in a row on their way to kindergarten for the first time (see Figure 4). It is a bright image: the various colors of the children's outfits stand out against the natural backdrop, and the blue-to-green-to-yellow of their tops makes a partial rainbow.Footnote 47 The accompanying three-page feature described the moment thus: “All dressed up in their new school clothes—blue-and-grey checked shirts for the boys and tartan skirts for the girls, with a yellow jumper for Alison and a green one for Judy.”Footnote 48 The girls were dressed in the same skirts, and the boys were dressed in the same outfits, but these were not uniforms. In accompanying photographs taken at the school, it was clear the Saras’ clothing did not match that of their peers. The quads’ appearance rather suggested a mother who, sewing their clothes at home, economized on the number of fabrics by duplicating items for her same-gender children.

Figures 4 and 5. The Sara quads go from being new kindergarteners (1955) to uniformly poised schoolchildren (1958). (Australian Women's Weekly, July 6, 1955, cover, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page4912055; and March 26, 1958, 48, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page4822550.)

In January of the following year, at the height of summer, the Sara family moved to the Sydney suburb of Punchbowl. The children started a new school, once again their local public primary school. The magazine described their progress in 1958 with the article “The Quads Are Growing Up,” noting that, at age seven, they were “now self-possessed schoolchildren.” The article was about a visit to a Sydney clothing shop. Like so many of the pieces about these children, this was essentially a staged photo opportunity. In this case, they were portrayed trying on regulation school outfits consisting of hats, blazers, and other items (see Figure 5).Footnote 49

The children had not begun attending a school with a compulsory uniform, but the Weekly nonetheless wished to give the impression that they had advanced to a new stage. In white-collared shirts and blazers, the girls in black and the boys in dark gray, the Sara quads no longer looked like their multicolored four-year-old selves on the way to kindergarten. Here, they appeared uniformed, and this was the magazine's way of visually fulfilling the hopes expressed at their birth: that the children would start out at the local school but then at some point, when they were a bit older, progress to schooling that was farther away, more selective, “better.” The quadruplets now looked like real-life versions of the uniformly dressed schoolchildren who had shown up in advertisements and elsewhere in the Weekly since the 1930s, and the aspirational message was that although it was fine for children to be dressed as individuals when they were just starting out at school, there came a time for them to advance to a level of superior education that required “self-possession,” conformity, and uniformity.

Debating Uniformity, Selling Uniformity

From the 1950s to the 1970s, the Weekly printed a series of readers’ letters on the topic of school dress. As previously noted, they had printed letters on the topic prior to this period, but now the letters appeared more frequently, amounting to more sustained coverage of the matter. These letters dealt with a variety of points and concerns, but they all focused on matters of regulation attire, and they accumulated to form an ongoing debate about the desirability of school uniforms. The letters were supplemented by a number of articles on uniform school dress. Many letters and stories framed such attire as beneficial, but occasionally one would be more negative or ambivalent in tone. Importantly, one side of this debate also featured in the Weekly’s advertisements during this period: even as the magazine facilitated an epistolary and journalistic conversation on school uniforms, it ran advertisements for the same by manufacturers of fabrics and ready-to-wear clothing. The Weekly created a space for debate on uniforms, but alongside it a space for selling uniforms.Footnote 50

By the 1950s, increasing numbers of students were wearing school uniforms. Many private schools and public secondary schools that had relaxed their rules on attire during the war because of clothes rationing—which in Australia ended in 1948—were now reinstating dress standards. Although most public primary schools did not have a tradition of uniforms, the Weekly printed a reader's letter in 1955 that gave voice to the impression that they too were moving in that direction:

In these days when color consultants stress the value of colorful surroundings, when color therapy is used and colorful clothes and dwellings are more in evidence than ever, is not the yearning of the powers-that-be to inflict school uniforms on State-run schools a backward step? Last Education Week, the junior school grouped for singing looked like a field of gay flowers. Next year if the suggestion of the school council is followed, we shall see regimented ranks of dull grey, and bad luck if your child looks ghastly in grey.Footnote 51

As the writer indicated, the adoption of a school uniform was a matter decided upon by a given principal, school council, and parent community. It was a local matter.Footnote 52 All the same, the writer had the sense that, by the mid-1950s, there were “powers-that-be” wishing to concertedly “inflict” uniforms on public school students in general. In saying that such a move would be a “backward step,” the writer was reminding readers that school uniforms in Australia were an artifact of the country's historic ties to Britain. Despite the fact that only a small minority of schoolchildren in nineteenth-century Australia had worn uniforms, such garments by the mid-twentieth century had come to serve as visual signifiers of traditional schooling, specifically the exclusive, fee-based model that had been imported a century prior from England.

Much content in the Weekly, however, took the opposite tack, emphasizing the modern nature of contemporary school uniforms. The 1958 piece “Uniform Revolution” sought to highlight how different compulsory school attire was at the turn of the century. There were references to “white frocks,” “leg-o’-mutton sleeves,” and bonnets with “tiers of starched frills.” The “first reaction” of modern mothers looking back at this was said to have been: “Think of the washing and ironing.”Footnote 53 Next to the article was a “back to school” advertisement for Joyce Non-Iron School Blouses (see Figure 6).Footnote 54

Figure 6. A photograph of schoolgirls at the turn of the century juxtaposed with an advertisement for new noniron school blouses (1958). (Australian Women's Weekly, Jan. 22, 1958, 29, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page4819849.)

Companies were now marketing their school clothing using easy-care language as well as modern-sounding trade names meant to set their fabrics apart: “Cesarine for school wear” was “Cesarised-shrunk,” giving “the required cotton-crisp freshness”; “Fasco” was “Actil-shrunk” and set “the fashion in school clothes.”Footnote 55 Ads such as these aimed to counter the impression that school uniforms required the elaborate maintenance of prior decades. Modern proprietary industrial garments were advertised to appeal not so much to the young people who would be wearing them as to the contemporary, efficient housewife who would, presumably, purchase and care for them.

Cotton-polyester blends had replaced natural fabrics such as voile and poplin. Items boasting “extra polyester” were sold at higher prices, with claims made about their durability. A 1966 advertisement for boys’ school clothing promised: “Your sons will look just as smart and wrinkle free after a long, hard school day as they did when they left this morning. If they're wearing 12½ oz. gaberdine Efco Toray Tetoron School Wear.”Footnote 56 The word “smart” was used in the British sense of being neat and well dressed, but its more American association with intelligence was not meant to be lost on readers. Other advertisements made the same kinds of connections between the well-groomed appearance of students and their potential for academic achievement. Tootal Tooform came in “all standard school colours” for the “smartest looking school uniforms.”Footnote 57 Caesar Fabrics, promoting girls’ school dresses, gave a snapshot of “The pen & pencil set … at their smartest in crisp, easycare Cesarine” and advised readers to “Join the smart set … ask for school uniforms of Cesarine.”Footnote 58 King Gee boys’ permanent press school clothes purported to solve challenges in both the classroom and the laundry room—they were “The answer to bad school marks … and stains and creases.”Footnote 59 Images and texts in these advertisements typically represented boys’ uniforms as tough and resistant and girls’ as neat and compliant.

In a move that suggested there were no boundaries to the regulating of school dress, even makers of undergarments began pitching their wares in these terms. Exacto Children's Wear sold Top-O’-The-Class Panties made “specially for school girls,” in “authentic school colors” and featuring “regulation leg length.”Footnote 60 Bonds advertised its girls’ briefs as getting “top marks for colour and comfort”: “And they come in school colours, too, to match your uniform! … Navy, Grey, Fawn, Bottle Green and Black.”Footnote 61 Bonds back-to-school briefs for boys were not only “top of the class,” but also worn by “the men of tomorrow.”Footnote 62

These advertisements worked to market the trope of the uniform-wearing schoolchild, not only to mothers whose children attended schools with compulsory attire but also those whose children did not. Although sewing patterns for homemade uniforms still appeared occasionally, there was an increasing emphasis over the period on advertisements for mass-produced clothing and its care. The Weekly complemented the ads with articles that did the same. The 1958 piece “Clothing Cues for the Classroom Set” made clear that it was the mother's job to ensure her school-going children were well groomed. This was framed as an accomplishment on the mother's part as well as an external sign of her adequacy: “Nearly every mother, of course, takes the greatest pride in making sure that her children are suitably ‘turned out’ for [the back-to-school] occasion.”Footnote 63 The article allowed that there were different circumstances in different households, but such things were not meant to detract from a mother's ability to send well-dressed children off to school. It was as if how one's children were “turned out” for school indicated how they would turn out in life.

Subsequent articles in the Weekly consolidated the message that proper school dress was tantamount to a school uniform. To dress children in something that was not a uniform was not acceptable. “Keeping the Uniforms in Order,” a 1969 back-to-school piece written by a mother, offered advice “to those who are facing the problems of school wardrobes for the first time.”Footnote 64 Nowhere did it acknowledge that school wardrobes might consist of something other than regulation attire. “School Gear—What to Buy,” a similar article from 1972 written by a schoolteacher, was divided into basic sections and began with “The Uniform.”Footnote 65

In the Weekly’s discourse of the uniformed schoolchild, America continued to be otherized as the place in which students dressed according to their own whims. A 1961 profile called “How a U.S. Girl, 15, Sees Us” began with the pull quote: “I took one look at your school uniforms and wanted to go back home!” The girl explained, “We don't wear uniforms back home and it took a bit of getting used to here.”Footnote 66 This view was underscored in a 1967 article on several of the teenaged participants in Science ’67, a television program covering the Summer Science School at the University of Sydney. This was the first year that the school had admitted non-Australians, and Nan Musgrove, the Weekly’s regular TV columnist, took it as an opportunity to focus a piece on three American attendees: Ellen, Nancy, and Cathy. These girls, aged sixteen and seventeen, had interests that, in addition to science, included philosophy, international relations, and flying Cessna aircrafts. Musgrove mentioned this, but her main concern was how they felt about topics such as “Australian Boys,” “Woman's Work” (“cleaning, cooking, baby-minding”), and “School Uniforms.” On the latter subject, the girls emphasized the importance of individual preference:

“At home we don't wear uniforms to school,” Cathy said, “and I'm glad.”

Nancy said it would save the daily chore of making a choice of what to wear, but she preferred that to uniforms.

I told them most Australians regarded uniforms as a leveller and garments that cut out competition among girls whose families had differing income levels.

Ellen thought that was rather bad thinking.

“If students are socially conscious about clothes and are forced to wear uniforms,” she said, “they will find other status symbols to fulfil their need.”

On the other hand, if they don't care about clothes it doesn't matter what they wear. It is all in the mind.”Footnote 67

Many Australian adolescents were taking their own stands against regulation attire in the pages of the magazine. Over the course of the 1960s, the magazine printed their letters as well as those from some of their peers in defense of compulsory school dress. This extended the debate on uniforms to include the opinions of high school students who wore them, at the same time that advertisers persisted in identifying mothers as the targets of information about the consumption and care of school dress.Footnote 68 Ross Holmes, in his letter “Why Have School Uniforms?,” wrote that uniforms were not only an affront to his individuality but also simply illogical: “Having to wear a hat, tie, blue shirt, and college-grey trousers, besides being unattractive, unfashionable, and uncomfortable, is (I feel) a denial of my personal freedom. In my primary school I did not wear [a] uniform, and if I attend university I will not be asked to wear it. So why is it that we secondary-school students are compelled to wear uniforms?”Footnote 69 John Boyd, in an unusually long letter (over two hundred words) entitled “Useless Uniforms,” accused headmasters and teachers of making “a fetish worship of conformity by forcing the young adults in their charge into largely unimaginative and often outdated uniforms” even as they “mouth[ed] platitudes urging students to think for themselves.”Footnote 70 The Weekly published several responses to Boyd in a subsequent issue: one from Marina Fusescu, who heartily agreed with Boyd and would “never understand why so much importance is placed on the wretched things”; one from Sue Hann, who, although she had shared Boyd's sentiments when a high school student herself, had now changed her mind after realizing the expense involved in maintaining a suitable wardrobe for her role as an office worker; and one from Margaret Henderson, who had heard from a friend in Ontario about the sartorially marked social groups in Canadian schools (the “‘in’ kids,” the “mediocre” ones, the “peasants,” the “rocks,” and the “greasers”) and had concluded, “At least in Australia we teenagers don't have to contend with such obvious snobbery. I think compulsory uniforms help to eliminate this sort of thing.”Footnote 71

The for-and-against exchange on school uniforms continued into the first half of the 1970s, both in the teen section and the magazine's main pages. In an array of points that largely overlapped with many of those made previously, the garments were said, on the one hand, to foster a sense of social cohesion and school belonging and present a homogenous group to the publicFootnote 72 and, on the other hand, to be senselessly tradition-bound, overly pricey, and subject to stereotyping.Footnote 73 The final Letter Box back-and-forth appeared in 1975, with two submissions in favor and two against.Footnote 74 These were written in response to an article entitled “Are School Uniforms Really Necessary?,” which pointed out, rather unnecessarily, that “opinions [were] divided.” Much of the piece featured experts (educational administrators, psychologists, and university faculty members) laying out the standard arguments for and against. But it also referenced a “ruling” by the New South Wales Education Department that students could not be forced to wear uniforms in the state's public schools. The department's spokesman made it clear that school uniforms were “not compulsory.” And yet even he felt the need to touch on both sides of the debate, noting that “the principal may find them desirable.” In turn, the article quoted the president of the Federation of Parents and Citizens of New South Wales as stating, “If the principal finds a uniform desirable, then parents and students should have a chance to discuss if and what it will be.” She explained, “The Federation has no policy on whether uniforms are necessary or not. … All we are concerned about is that the children are not penalized if they don't wear the uniform.”Footnote 75

Although many primary schools by the 1970s had opted for items of standardized clothing for students, not all families in such schools were conforming to the standards. This reality was reflected in a 1977 advertisement by the boys’ school wear company King Gee. The ad took up a full two pages and bore the heading, “King Gee school wear beats the pants off anything else” (see Figure 7). It showed sixteen schoolboys in a variety of scenes. The majority of the boys are in King Gee garments—collared shirts and trousers or shorts in the traditional colors of gray, blue, brown, khaki, and white—along with conventional black leather “school shoes.” Those in the minority are from families that have declined to follow any school dress regulations—these boys are wearing jeans, T-shirts or sweatshirts, and running shoes. The scenes have a pattern: where four boys are running, the King Gee boys are ahead of the jeans-wearing boys; where boys are climbing a cannon, one King Gee-clad boy is helping another find his footing, while a jeans-wearing boy hangs off the end; where boys are playing ball, two King Gee boys are at the front, ready to catch the ball, while a boy in jeans is positioned hopelessly behind them; and, finally, where two boys are wrestling on the ground, the King Gee boy is sitting on top of the other one. Mandating uniforms may not have been allowable in public schools but it was perfectly fine in advertisements. As King Gee put it, “You're sick of high prices for uniforms, right? So you send him to school in ordinary clothes, right? Wrong.”Footnote 76

Figure 7. A two-page advertisement showing schoolboys in uniforms outperforming those in jeans. (Australian Women's Weekly, Jan. 26, 1977, 60–61, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article55475895.)

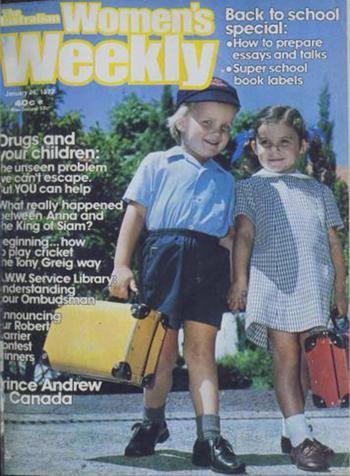

In the end, the Weekly made clear its own stance on school dress through a series of annual back-to-school covers that ran in late January from 1974 to 1981.Footnote 77 The covers effectively presented a visual resolution to the magazine's long-running debate on school wear, and through them the Weekly communicated an unequivocal position in favor of uniform attire. The magazine previously had run covers of children on the way to school—recall the 1955 cover of the Sara quads walking to kindergarten. Another especially notable one was a 1954 illustration called “School Bus” by the magazine's longtime lead artist, William Edwin Pidgeon.Footnote 78 It featured a bus interior dominated by a number of gleefully unruly young students. The children's clothing evokes the chaos of their behavior, their dress ranging from striped T-shirts and Tweedledee beanies to the traditional uniform of blazer, tie, and designated school cap. To the extent that the reader was meant to imagine the backstory of these cartoonish kids, the implication was that they either attended all kinds of different schools or showed up to the same school dressed in all kinds of different ways.

By the 1970s, however, the Weekly had narrowed its depictions of schoolchildren into a particular trope. In a series of back-to-school covers that began in 1974, not only did each child wear a uniform, each one wore specific regulation-style outfits, all predominantly blue in color.Footnote 79 These covers did not offer pictures of diversely dressed children, nor of children variously adhering and not adhering to a dress code. Rather, they presented images of children dressed correspondingly, all of a piece, both within each cover and across the series from year to year. All the girls were shown in blue and white, most in checked or plaid dresses. The boys were even more alike in light-blue collared shirts and gray or dark blue shorts. With these blue-clad schoolchildren, the Weekly offered its readership a vision of what Australian students were supposed to look like, with the implication that this was a vision made possible by Australian mothers.

The magazine's description of its 1974 back-to-school cover, the first in the series, referred to the featured “cover family”: two sisters and one brother—Lisa, Nicole, and Richard McDonald—who lived in the wealthy Sydney suburb of Mosman. The image of these children, smiling and forward-looking in their impeccable school wear, set the aspirational tone of the series. Contained inside this issue was a brief item entitled “Poll on School Uniforms.” If the McDonald cover children represented the idealization of school-uniform wearing, the poll by Morgan Gallup served as the substantiation of the practice. The “Australia-wide survey” of more than eighteen hundred people asked, “In your opinion, should all children at school wear uniforms, or what they like?” On average, seven out of ten responded in favor of uniforms, but support was higher among women compared to men, and those over age twenty compared to teenagers. Those least in favor of uniforms were said to be recent immigrants: “non-electors, mostly of European origin.” The message was clear—the native-born Australian women who were indicated in the very title of the magazine were those most in favor of school uniforms.Footnote 80

It was the 1977 cover in this back-to-school series that was arguably the apotheosis of the Weekly’s representations of the child dressed for school. It showed a boy and girl holding hands, he in a blue shirt, shorts, and cap, and she in a blue-and-white-checked dress and blue hair ribbons (see Figure 8). Editor-in-chief Ita Buttrose wrote in the issue's editorial, “I hope you'll forgive a mother's pride but that's my son, Ben, on the cover this week, and I think he looks absolutely fantastic. He's with his cousin, Rebecca—my niece—so the aunt in me feels pretty good too.”Footnote 81 Buttrose had started out at the magazine in the 1950s as a teenaged copy editor. By 1977, she was editor-in-chief not only of the Weekly but also of Cleo, a magazine for young women that she had launched in 1972. Her influence over Australian culture was so great that it would soon become the subject of a rock song called “Ita,” which included the lyrics:

Figure 8. The editor-in-chief's son and niece ready for school. (Australian Women's Weekly, Jan. 26, 1977, cover, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page5848335.)

In putting her son on the cover, Buttrose was building upon decades of advertisements and illustrations showing the well-turned-out schoolchild (the two-page King Gee spread was included in the same issue). Ben appeared to be setting out on his very first day of school—his smile was full of baby teeth. His mother took the opportunity to comment not on his emotional readiness, or his understanding of school, but on his appearance: he looked “absolutely fantastic.”

Conclusion

From its foundation in the 1930s through to the 1980s, the Weekly sought to generate popular interest in the question of how the Australian schoolgirl and schoolboy should be dressed. The mother who initiated the muumuu correspondence discussed at the beginning of this article eschewed the word uniform in favor of the more general word clothing—after all, if her daughter had attended a school with mandatory dress, the question of the muumuu would not have arisen. Readers would have realized this, but some of those who responded used the word uniform nonetheless. Tellingly, they did so in different ways. One contrasted a school uniform with a muumuu; another suggested a “muu-muu-type uniform.” For one, the word seemed to mean a compulsory school outfit; for the other, it meant the clothing that an individual child wore to school. The appearance of both usages in the same conversation suggests a variety of meanings and practices across Australia related to the clothed body of the midcentury schoolchild, and points to the lack of absolute rules in the majority of schooling jurisdictions.

If children could not be forced to wear school uniforms, if public schools were not actually allowed to make such attire compulsory, even if the principal wished to, upon what basis could a nonuniformed child be seen as in the wrong? This was the question of the spotted muumuu. The answer could be found in the very publication to which the mother of the muumuu-wearing schoolgirl had appealed, the Australian Women's Weekly—in the back-to-school advertisements and accompanying articles that for decades had made “regulation” school dress seem like the only correct option.

In a study of Cleo magazine, Megan Le Masurier observes that “the response of the ‘ordinary’ reader” cannot be “assumed as readable from the text.”Footnote 83 In this spirit, this article is not a social history of readers’ responses. We do not have systematic data about how the magazine's readers interpreted, acted on, objected to, or even scoffed at the Weekly's images and stories about school dress. Rather, this article is a cultural history underpinned by a belief in the power of public discourse. We argue that the magazine used the range of its content—providing textual and visual reinforcement of a powerful cultural trope of the proper and desirable Australian schoolchild as uniformed—to manufacture, moderate, and, in the end, resolve a national “debate” on the subject of school uniforms in their gendered forms.

Considering the pros and cons of uniform policies made a comfortable controversy for the Weekly: contentious enough for lively and ongoing exchanges but not so difficult or confronting that it would fail to appeal to the mass market. The 1974 opinion poll was a moment in which the magazine explicitly positioned itself as a cultural agent and authority on the matter. More often, the Weekly addressed and monetized school wear through a loose and cumulative aggregation of different kinds of copy: letters, advertisements, columns, and reporting. Visual imagery was perhaps the most important element in all of this. By the 1970s, full-color photographs of happy, uniformed children became a staple of the magazine's coverage of schooling. These images contained a messaging power that related to—even as it far outweighed—that of the ancillary for-and-against exchanges of readers, offering some insight into the increasing acceptance of school uniforms during the period.

An examination of this magazine also makes more visible the incorporation of mothers into the gendered labor of schooling—and the influence of the school in shaping their lives, work, and consciousness. Mothers, from Betty Sara to the various authors of the muumuu correspondence, experienced the domain of school clothing as a particular field of expertise: through their shopping, laundering, and outfitting, they made judgments and expressed options. At least, this is how they appeared in the pages of the magazine. The Weekly represented uniformity as a hallmark of a good and proper education, and the uniform-wearing student as having the ease and confidence of the one more likely to succeed. Behind every appropriately dressed child, the magazine seemed to suggest, was a savvy and competent mother.

The Australian Women's Weekly mainly represented school uniforms as something that schoolchildren (and their mothers) had in common, despite the Australian practice of using details such as crests or colors to differentiate between schools. The magazine was a publication about cultural majority, about belonging: it indicated that the students of Australia were achieving an advisable middle path between the stuffy traditions of Britain and the permissive individualism of America. And, therefore, although the distinctive uniforms of particular elite schools were sometimes featured or evoked, by the 1970s it was the more generic look being adopted by public primary schools that received more emphasis in the magazine's representations of the Australian student. The magazine had seen fit to frame the school uniform as a modern set of garments, made of easy-care fabrics meant to appeal to the presumed contemporary outlook and labor-saving priorities of the “housewife” reader. The emphasis was on a universal look, rather than on the differences between schools. The uniformed schoolchild thus became an embodied expression of Australia's egalitarian values. The Weekly rendered uniformed schooling as not only desirable, connected directly or indirectly to the sartorial history of exclusive or selective schooling, but also as obtainable and maintainable. As Buttrose's expression of motherly pride suggested, dressing one's child in, for example, a blue “regulation” outfit was a way of enacting the values of this women's magazine—and thereby entering its collective world.