IntroductionFootnote 1

For decades, scholars outside the field of African art history have either explicitly or implicitly questioned African art specialists’ use of sources and evidence. In 1984, historian Jan Vansina opened his book Art History in Africa with the assertion that “too many scholars in the field of ‘African art’ have been allergic to historical pursuits.”Footnote 2 Vansina demonstrates how Africanist art historians could better scrutinize sources and situate their studies of art within historical frames. Nine years later, historian William A. Hart echoed Vansina when he characterized Africanist art historians as “often highly selective and superficial in their use of historical documentation.”Footnote 3 Anthropologist Wyatt MacGaffey also critiqued art historians’ interpretations of meaning and their uses of sources in 2013, when he wrote, “It is a basic scholarly responsibility to provide some evidential basis for imputed meanings or to admit that they are speculative.”Footnote 4 Africanist art historians have long acknowledged that few specific details accompany many of the objects they study, and they have long relied on indirect evidence to situate objects in time and place. But as Vansina, Hart, and MacGaffey observe, interpretations of art and its past or present contexts have often rested on glossed-over speculations rather than irrefutable information.

Our adoption of computational methods to study arts identified as Senufo – one of the most celebrated styles of so-called historical or traditional African arts since the early twentieth century – has led us to reevaluate sources, examine the nature of evidence, and reflect on the subjectivity inherent in knowledge production in productive ways.Footnote 5 Mapping Senufo: Art, Evidence, and the Production of Knowledge – an in-progress, collaborative, born-digital publication – began with an effort to map geographic locations linked to objects labeled as Senufo. We thought a relative abundance of field-based documentation from the nineteenth century to the present for the corpus would allow us to determine locations, plot points, and identify patterns. As we started to build a map, we recognized that the quality and character of recorded information vary, and certain details that seemed specific eluded verification. Questions about the field-based data we gathered abounded. Consequently, we reconfigured the project to highlight the subjective nature of field-based documentation. We now aim to underscore possibilities and limitations that such information affords art enthusiasts and other curious people who seek to know about local agency or specific histories.

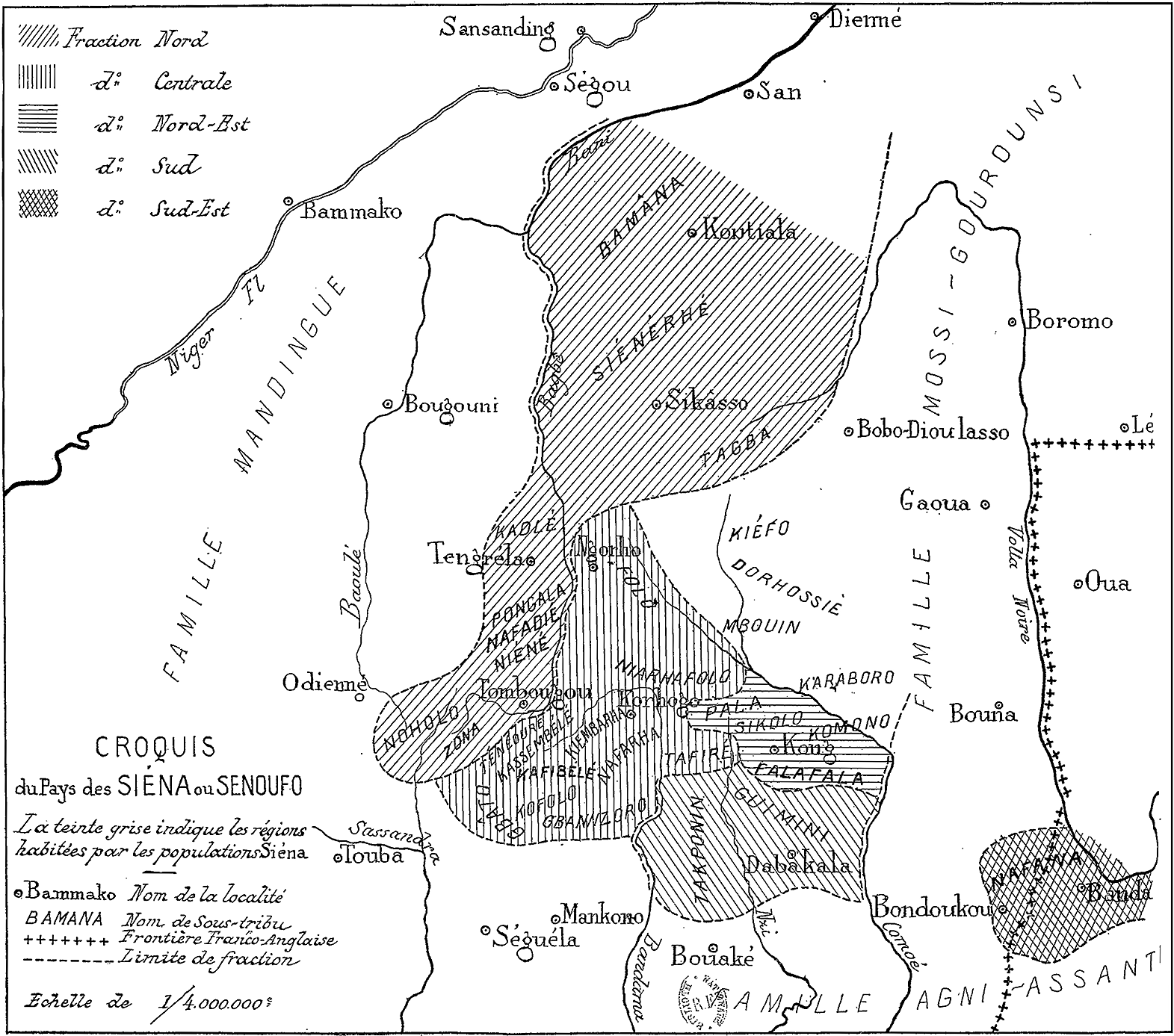

The term Senufo and variants of it appeared in French publications by the end of the nineteenth century. In an 1887 issue of the French journal Revue d’ethnographie, a Dr. Tautain used a variant of the term Senufo. Tautain refers to “Sénéfo” farmers and town leaders. He also mentions other groups. He notes distinctions among groups as well as intermingling.Footnote 6 During the first decade of the twentieth century, French colonial administrator Maurice Delafosse attempted to define and delimit Senufo as a discrete group with its own characteristics and geography.Footnote 7 In an article that Delafosse published in two installments, the colonial administrator focuses on populations he regards as “Siéna” or “Sénoufo” and characteristics of the group. The first installment of the article, published in 1908, includes a map illustrating the extent of a so-called Senufo country (Fig. 1). The shape and scope of the geographic area Delafosse presented as Senufo endures to the present.Footnote 8 Yet scholars have also increasingly examined the complex and heterogeneous nature of languages and identities in the same region.Footnote 9

Figure 1. Sketch of the country of the Siéna or Senufo. From Delafosse, “Le peuple siéna ou sénoufo,” pl. 1.

The area Delafosse designated as Senufo extends across the present-day borders of Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Mali. Throughout this article we refer to the area as the three-corner region.Footnote 10 We recognize our references to the three-corner region are at times anachronistic. The phrase nevertheless designates a geographic area without insisting on its connection to a singular cultural or ethnic group.

Senufo as a term exists, and throughout the twentieth century, it was applied to a corpus of objects from West Africa that entered European and North American art collections. But understandings of the term and its meanings vary from person to person and context to context. Once we realize Mapping Senufo as a digital monograph, the publication will offer a model for accentuating and investigating divergent ways of knowing through digital research and publication methods. The project joins theories about the construction of identities and politics of knowledge production with actual research and publication practice.Footnote 11 It also reflects our commitment to taking seriously the long-established understanding that a marker of identity, like the labeling of an art style or knowledge itself, is historically constituted, fluid, and positional. The open-access, multimodal publication that the Mapping Senufo team will produce will exemplify the contingent nature of identities, art-style labeling, and knowledge production. It will also harness the interactivity of digital environments to make explicit readers’ active participation in knowledge construction.

Digital humanities scholarship often emphasizes the iterative nature of research and foregrounds processes.Footnote 12 In this article, we examine our methods and explain how they inform the digital publication design the project team is developing. Our desire to plot geographic locations linked to objects led us to reassess different kinds of evidence. We are finding productive discrepancies between information furnished through historical sources and assumptions long shared by art historians, curators, dealers, collectors, and other enthusiasts. We are developing ways to attend to uneven collection, recording, suppression, and interpretation of evidence. We are embracing gaps and messiness instead of aiming to weave disparate details into a generalizing single story.Footnote 13 We are also encouraging reflection on the ways in which various individuals have asserted expertise through the production and codification of observations and assessments often viewed as facts. We posit that the form of a digital publication itself can bring processes of knowledge construction to the fore and unsettle expectations of a tidy, authoritative narrative account. As an alternate mode of scholarly publication, one that relies on the interactivity of the digital environment, Mapping Senufo in its final, version-of-record configuration will invite readers to enact our argument about the subjectivity and contingencies inherent in knowledge production.

The project requires us to reexamine familiar historical sources and to consider ever-changing approaches to intellectual inquiry. We are also working to identify and assess less familiar sources in order to rethink what we think we know, raise fresh queries, and point towards future avenues of study. Our approach coincides with the calls of historian David Newbury, who argues that historiography must remain central to historical analysis and that scholars of the past should return again and again to available sources and writing about them in order to re-evaluate understandings. He further asserts that scholars should resist selective histories and instead search for a range of perspectives, including assessments that come from their counterparts in other fields and disciplines.Footnote 14 For historians, including art historians, embrace of an historiographic approach requires willingness to set aside prior assumptions, and to accept that we may not know as much as we would like to know, or what we thought we knew. Newbury further makes clear that selective reading and reasoning in the telling of the past can translate into real political consequences with significant life-and-death outcomes.Footnote 15 The Rwandan case at the center of Newbury’s research may provide a particularly stark example of the political consequences of selective historical narratives, but it should also serve as a caution.

Reframing Research Questions

Mapping Senufo emerges from our prior work together on Senufo: Art and Identity in West Africa (2015), a major international exhibition organized by the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA). Gagliardi wrote the book Senufo Unbound: Dynamics of Art and Identity in West Africa (2014) that accompanied the exhibition.Footnote 16 Petridis, then curator of African art at the CMA, selected objects for the show and installed them to present Gagliardi’s thesis within a three-dimensional space.Footnote 17 Through Gagliardi’s book and the exhibition it informed, we deconstructed the term Senufo and its limited usefulness in providing an all-encompassing, definitive explanation for a category of art. We investigated the colonial context in which the term first appeared in French publications at the end of the nineteenth century. We examined how art connoisseurs and other enthusiasts applied the Senufo label to a growing number of objects from Africa arriving in Europe and North America in the early twentieth century. The project contributed to discussions about the constructed nature of identities, assumptions embedded in them, and the relevance of classifying or assessing arts within certain groups. The endeavor left us with unresolved questions about the specificity of individual objects, their trajectories, and firsthand knowledge about them. The questions became fodder for continued collaboration.

The Legacy of Robert Goldwater’s Senufo Sculpture from West Africa

The 1963 exhibition Senufo Sculpture from West Africa has served as a starting point for our second project. The exhibition and its companion publication of the same name consolidated understandings of Senufo arts based primarily on foreigners’ observations during the first half of the twentieth century, and the show and book have served as foundations for subsequent studies. When the exhibition opened in New York at the now-defunct Museum of Primitive Art (MPA) on 20 February 1963, it presented art enthusiasts with parameters for evaluating formal qualities of objects and classifying them as Senufo. The exhibition also marked the second time ever that the MPA or any art museum in North America or Europe devoted an exhibition to a single style of African art. Senufo Sculpture followed the MPA’s 1960 show Antelopes and Queens: Bambara Sculpture from the Western Sudan, its first exhibition dedicated to a single style of African art.

Robert Goldwater, who served as the MPA’s director when the exhibitions opened, published a book in conjunction with each show.Footnote 18 In the two books, Goldwater sought to examine the cultural contexts for arts he recognized respectively as Bambara, or Bamana – the latter term now more commonly used in English – and Senufo. Goldwater located populations he regarded as Bamana and the arts he attributed to them to a central area of present-day Mali, and a northern part of present-day Guinea. He located populations he considered as Senufo and the arts he attached to them in an adjacent area that extends across the three-corner region.

Goldwater opened his book Senufo Sculpture from West Africa with the phrase “the Senufo people” and seemed throughout the text to try to supply a comprehensive view of what he called “the Senufo.” His language subtly implies that each person and town identified, or identifying as Senufo, were nearly the same as all other people and towns regarded as Senufo.Footnote 19 He similarly attempted to describe “the Bambara” in the earlier book.Footnote 20 Goldwater’s approach reflects then-common assumptions about the African continent south of the Sahara, namely that the distribution of art styles coincided with the distribution of cultural or ethnic groups and that group characteristics superseded individual particularities.Footnote 21

Goldwater did not conduct his own research in West Africa and instead relied on other observers’ accounts to inform his analyses. While Goldwater supplied broad descriptions of Senufo and Bamana arts and cultures based on the sources he consulted, he also endeavored to account for specificities of place within the areas he recognized as Senufo and Bamana as well as the variable nature of sources he used to make place-based assessments. His attention to such details evinces a desire for more nuanced understandings of objects’ origins, as well as concern for the quality of evidence used to make a claim. A legend Goldwater reproduced in each publication indicates that an F next to a place-based attribution for an object designates “direct information from field collectors;” A refers to “indirect information and attributions by other collectors;” and S applies to “attributions on stylistic grounds by the Museum of Primitive Art.”Footnote 22

The attributions Goldwater printed in his books feature varying amounts of place-based data. The broadest attributions in Senufo Sculpture from West Africa identify objects with particular areas – northern, central, southern, southeastern, or western – within the larger three-corner region. At times, the designations link objects to certain districts within one of the areas in the larger region. On occasion, the assignments even locate objects to particular settlements. And in some cases, Goldwater’s attributions link an object with a particular “fraction,” or subgroup, of the larger Senufo group. For example, Goldwater offers “Central region, Korhogo district, Lataha village, Kiembara fraction” as specific information for a nearly four-foot-tall male figurative sculpture that politician and MPA founder Nelson A. Rockefeller acquired in 1958 and subsequently loaned to the museum (Fig. 2). An F next to the attribution indicates that it reflects “direct information from field collectors.” A note following the F reads, “collected by Emil Storrer,” thus suggesting that Storrer, then an art dealer based in Zurich, Switzerland, provided Goldwater with the information that Storrer had obtained during his own travels in northern Côte d’Ivoire.Footnote 23

Figure 2. Unrecorded maker. Male figure. Wood, h. 108 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1965 (1978.412.315). Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY.

As scholars know well, the ability to situate an object, or any other historical source, within a particular place and time makes historical analysis possible.Footnote 24 More precise information about when, where, why, how, and through what individual’s or organization’s actions a source came into being seems to portend the possibility for greater insight. Yet information that seems precise could actually reflect speculation disconnected with historical and geographic verities. When an object’s style is identified as Senufo, the label suggests but does not on its own confirm that the object is locatable to the three-corner region. The same label points at but does not prove that the work’s original maker, patron, or audience identified as Senufo.

Mapping Goldwater’s Place-Based Attributions

Goldwater’s geographic attributions for 132 of 161 objects illustrated in his book may appear to provide additional place-based details as well as suggest opportunities for more extensive investigations of individual objects and the history of each object. However, Goldwater’s assessments of distinct areas linked to particular objects and the rationale for his evaluations demand more attention.Footnote 25 In fact, an urge to investigate the sources Goldwater used, and to find independent, corroborating evidence for Goldwater’s place-based attributions, sparked our initial development of Mapping Senufo. We imagined using information from a number of different sources to create a multilayered map that would permit us to confirm or revise the geographic distribution of forms proposed by Goldwater.

At first glance, Goldwater’s indication that place-based attribution for the male figurative sculpture Rockefeller purchased from Storrer reflects “direct information from field collectors” could imply for some readers a reliability and completeness of information (Fig. 2). American art historian Anita J. Glaze’s subsequent enthusiasm for a photograph reportedly taken in the same locale hints at a possible impulse to uphold any observer’s field-based information as accurate and important. Yet the phrase field collector, in this context, could refer to any person who reportedly acquired an object from the three-corner region. The phrase does not specify a person’s interests, investments, or expertise in accurate documentation or the subject matter. And even if we accept reports that Storrer or any other foreigners viewed the male figurative sculpture in Lataha or photographed sculptures in the town, a location yields only a sliver of information and requires more investigation into the production, use, and circulation of the works at a particular moment.

While F, meaning “direct information from field collectors,” in Goldwater’s book may imply the most reliable sources for the author’s place-based assessments, the information Goldwater supplies under this banner does not appear solid when subject to further scrutiny. Furthermore, Goldwater relies on “direct information from field collectors” to make only 26 of the 132 placed-based attributions in the book. For the sources he used to make 21 of the 132 attributions, Goldwater assigns an A, signaling that some other collector provided place-based information for an object. Goldwater does not clearly name the sources for the assessments. In a few instances, he specifies details in conjunction with the designation that we have not yet been able to crosscheck. For example, Goldwater indicates that a staff in the collection of Paris’s Galerie Le Corneur-Roudillon in 1964 “belonged to King Babemba of Sikasso,” and was “collected in 1898,” the year that the French government seized control of the city of Sikasso in present-day Mali.Footnote 26 If the staff did indeed ever belong to the ruler of Sikasso, then the object would have singular historical significance. But we need to locate more information to substantiate this claim.

The rest of Goldwater’s place-based attributions depend on stylistic comparison, a method art historians and art enthusiasts employed throughout the twentieth century to find similar qualities among objects and then assign a geographic origin to the set.Footnote 27 The method has facilitated analysis of objects from around the world for which we have little, if any, specific documentation about their creation or use. It is also subjective and not infallible. With scant detail to assess objects Goldwater or his colleagues at the MPA labeled as Senufo, the museum’s staff used the method to identify 85 of 161 objects with a particular region, district, or smaller locale within the larger three-corner region. Goldwater occasionally identifies specific field-based information that served as a basis for a particular stylistic comparison. In one instance, he links two face masks with beak-like elongations to the northern region due to their formal similarities to a face mask that a man known as F.-H. Lem wrote he acquired in the Folona, an area in the southeastern part of present-day Mali (Fig. 3).Footnote 28 No other evidence appears to buttress the claim.

Figure 3. Unrecorded maker. Face mask comparable in form to an example that F.-H. Lem reportedly acquired in the Folona, an area in the southeastern part of present-day Mali. Wood, pigment, 40.6 × 15.2 × 8.9 cm. The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1969. Accession Number: 1978.412.365. Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY.

Goldwater’s sources for stylistic comparison vary significantly. He indicates that an unidentified collector attributed a pair of nearly four-feet-tall figurative sculptures to the northern region. Goldwater’s place-based designation also includes a question mark to suggest the pair may or may not be located more specifically to the San district within the northern region.Footnote 29 Based on stylistic comparison, someone at the MPA linked three other tall figurative sculptures of somewhat comparable height to the same region and possible district.Footnote 30 In other instances, Goldwater does not specify the bases for stylistic comparisons, thereby making it difficult to evaluate the credibility of the assertions. And Goldwater indicates no localized geographic attributions for another 29 of the 161 illustrated objects.

The few examples we have highlighted here show that Goldwater’s designations serve as starting points rather than end points for analysis. They also prompt us to consider whether recovery of details about who exactly made objects in the Senufo corpus or where, when, why, how, or for whom the makers did so will ever be possible. Available records may never lead to such disclosures. But we may strive to acknowledge unrecorded or otherwise unavailable specificities of individual objects and their histories when we write about the arts rather than presenting them with certainty that our sources cannot uphold. And we may sit with the partiality and incompleteness of any knowledge instead of trying to resolve all gaps.Footnote 31

With the aim of producing a multilayered map in mind, we gathered data from other observers of Senufo arts who linked individual objects with specific locales in their notes and publications. We also worked with members of the project team to create a relational database and plot points.Footnote 32 As we added points to the map, we noticed that they seemed to imply certainty. Yet for many of the points we plotted, we found we had more ambiguous than steadfast information for determining locations. The character of place-based information also varied from object to object. A place linked to an object could designate a reported location of documentation or reported site of acquisition. Or it could name a locale reportedly associated with the life or work of a person credited with making the object.Footnote 33 We sought methods to render the ambiguity visible to our readers. We also realized that we needed to take a closer look at our sources.

Reevaluating Sources

The variability and inconsistency of field-based data highlighted through our digital methods propelled us to reexamine the nature of our evidence and shift the project’s focus to a study of the quality and character of information about Senufo arts. One part of the ongoing effort returns us to Goldwater’s landmark study and the key he provided to distinguish among different types of place-based information. An examination of Goldwater’s evaluations and evidence he offers to support his assertions demonstrates the instability of information that art enthusiasts have often regarded as stable because it derives from an observer’s time in “the field.” As Vansina noted nearly four decades ago, observers’ statements vary in reliability.Footnote 34 With Mapping Senufo, we seek to demonstrate that scholars may present variability rather than attempt to resolve it. Study of Goldwater’s assessments also points at the need to return to familiar sources and uncover unfamiliar ones in order to refine and expand our knowledge about the arts and complex histories connected to the making, use, and circulation of objects in disparate times and places.

Looking Back at and Beyond a Photo from a Clearing in Lataha

Sources apparently from a town known as Lataha offer a case in point. Goldwater locates 21 of 161 objects published in Senufo Sculpture from West Africa to specific towns in the three-corner region. Two of the 21 objects he identifies with Lataha. Since the mid-twentieth century, art scholars, dealers, collectors and other art enthusiasts have connected Lataha with a number of significant sculptures in the Senufo corpus. Several authors have also referred to makers of sculptures linked to the town as the Master of Lataha or as the Master of Lataha I and Master of Lataha II.Footnote 35 A photograph published in July 1953 showing sculptures in a clearing among trees as well as other photographs that the French Catholic missionary Gabriel Clamens and his colleague Michel Convers presumably took during the same visit have at times been taken as evidence of some of the sculptures’ location in Lataha (Fig. 4).Footnote 36 But the name of the town has not always accompanied the photographs.

Figure 4. “Masques du porro sénoufo. (Photo: G. Clamens.)” From Clamens, “Notes d’ethnologie sénoufo,” 79, fig. 4. Courtesy of the Institut Fondamental d’Afrique Noire Cheikh Anta Diop, Dakar.

When Clamens’s photograph of sculptures in the clearing appeared in print in 1953, the missionary explained he decided not to reveal the name of the site where the men captured the image. Thirty years after Clamens published the photograph, the American scholar Glaze praised the missionary for the image as well as his prudence in not disclosing its exact location. She described the author as “perhaps the most able and conscientious of early sources on the Senufo.”Footnote 37 Based on a comparison of a single sculpture in the photograph with another sculpture linked to Lataha but not present in the image as well as her own research on Senufo arts, including extended fieldwork in northern Côte d’Ivoire, Glaze concludes that the sculpture may have come from a locale “near the Korhogo / Sinematiali axis, either Lataha itself or one of its sister villages such as Serijakaha or Warinyene.”Footnote 38 Glaze’s statement suggests that by 1983, art scholars and enthusiasts had not yet determined a location for the photograph. The connection of the photograph with Lataha seems to have become more fixed later in the decade, and in 1991, Clamens’s colleague Convers explicitly connected the photograph published in 1953 to Lataha.Footnote 39

Other evidence suggests foreigners regarded Lataha as a town that housed compelling sculptures in the early 1950s. The missionaries’ photograph published in 1953 does not show the male sculpture that Rockefeller acquired from Storrer (Fig. 2). In 1991, Convers linked the sculpture to Lataha.Footnote 40 Art enthusiast and self-published author Burkhard Gottschalk reinforces the idea of the sculpture’s connection to Lataha in a book on a movement known as Massa. Gottschalk also publishes a photograph of the sculpture standing between two other objects. He attributes the image to Louis Morla and asserts that Morla photographed the three objects in Lataha.Footnote 41 Storrer also reportedly traveled to the town at some point in the mid-twentieth century. In a 1 November 1957 letter addressed to Goldwater, who consulted with Rockefeller on the politician’s African art purchases as well as on acquisitions for the MPA, the Swiss art dealer notes that he had previously visited Lataha. Storrer further explains that he had seen the male figurative sculpture in the town but actually acquired it in Korhogo, a city located about ten miles south-southwest of Lataha. Storrer adds that he obtained the object at a time when people across the three-corner region and beyond sought to transform their practices as part of the movement often referred to as Massa.Footnote 42

In some places in the three-corner region, people who turned to Massa in the late 1940s and early 1950s discarded objects or replaced them with new ones.Footnote 43 However, the coincidence of the movement and acquisition of objects in northern Côte d’Ivoire does not prove that people in the area had discarded the acquired objects as a result of the movement.Footnote 44 A variety of other motivations or actions could have precipitated the objects’ transit from northern Côte d’Ivoire. Questions about the movement, the strength of its presence in Lataha, and its connection with objects that Storrer, the French Catholic missionaries, and other foreigners in northern Côte d’Ivoire documented or acquired demand attention. Additional uncertainty about the specific political, economic, and artistic contexts within Lataha and among towns in the area at the time also require consideration in order to gain greater historical understanding.

A set of some two-dozen images from the clearing, many of them unpublished, includes the photograph the missionary Clamens published in July 1953. The photographs seem to relate to the same moment and hint at happenings in the clearing when Clamens and his colleague Convers visited it with a camera.Footnote 45 Images in the set show sculptures standing in a line within a restricted space. As Gagliardi has addressed elsewhere, the images differ from other photographs of objects tossed into heaps within wide-open spaces from northern Côte d’Ivoire taken around the same time.Footnote 46 Observers, including Clamens and Convers, have more directly linked the latter photos to Massa.Footnote 47 While Clamens refers to Massa in his 1953 article, he limits his discussion of it to the first part of the article. He refers to the images from the clearing only in the second part of the article, which he does not explicitly link to Massa. The visual and textual mismatches suggest that the events in the clearing differed at least in some ways from the events related to the disposal of objects as a result of Massa.

We may never be able to recover accounts from everyone who gathered in the clearing when the missionaries captured photographs of sculptures standing there, but we can still show that a number of people contributed to what happened there. One photograph in the missionaries’ set shows Convers in the center of the frame, towering over the aligned sculptures. A fuller account of events that unfolded in Lataha on a single day and over time would identify the other men in the images as well as assess why a group of sculptures standing in Lataha but not in another town in northern Côte d’Ivoire attracted the attention of a number of foreigners, including the Swiss art dealer and the two French Catholic missionaries. Mapping Senufo will make visible absences in documentation we have consulted and highlight untold stories we do not yet have evidence to elucidate in detail.

1907–1909 German Inner-African Research Expedition

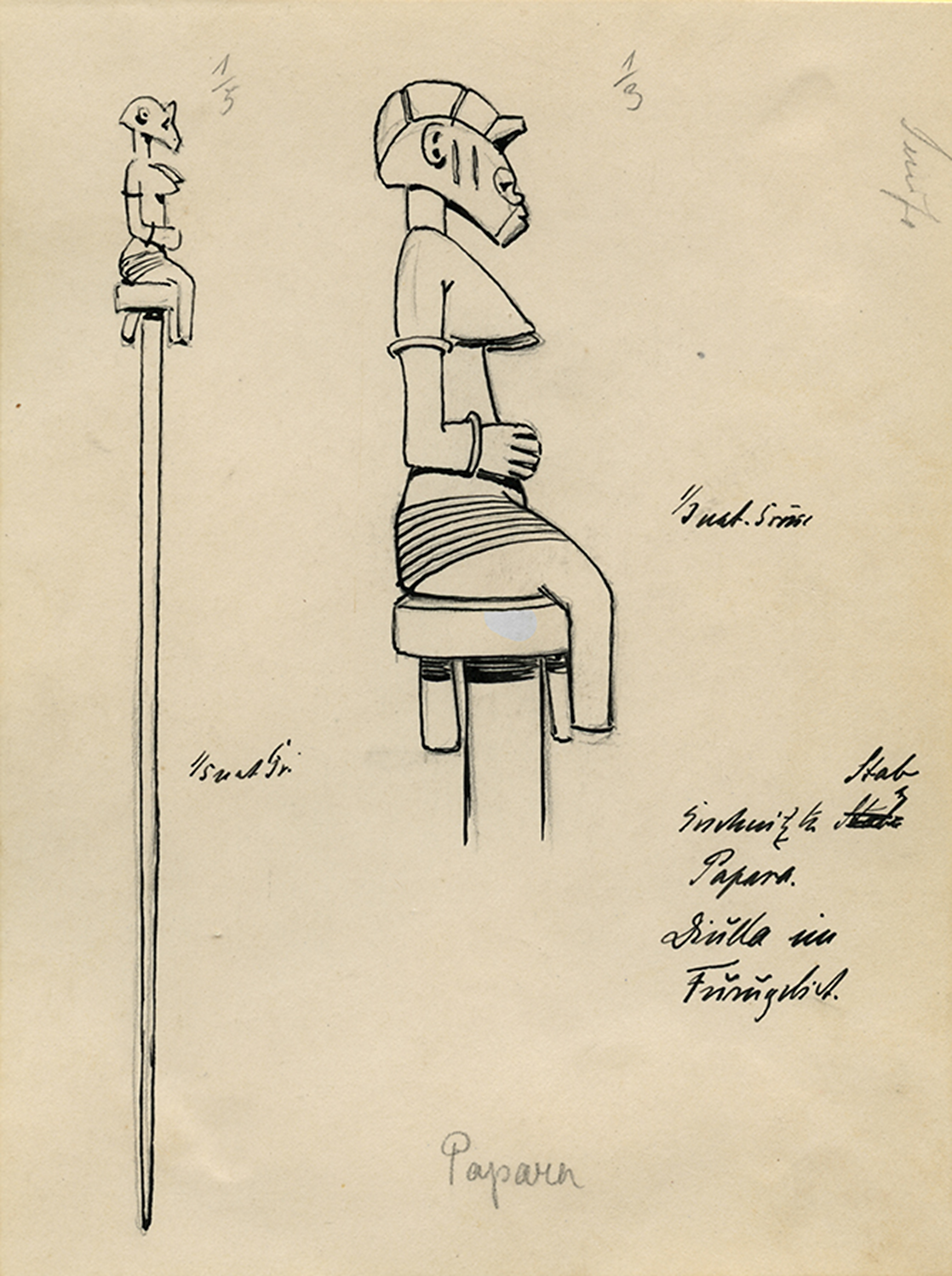

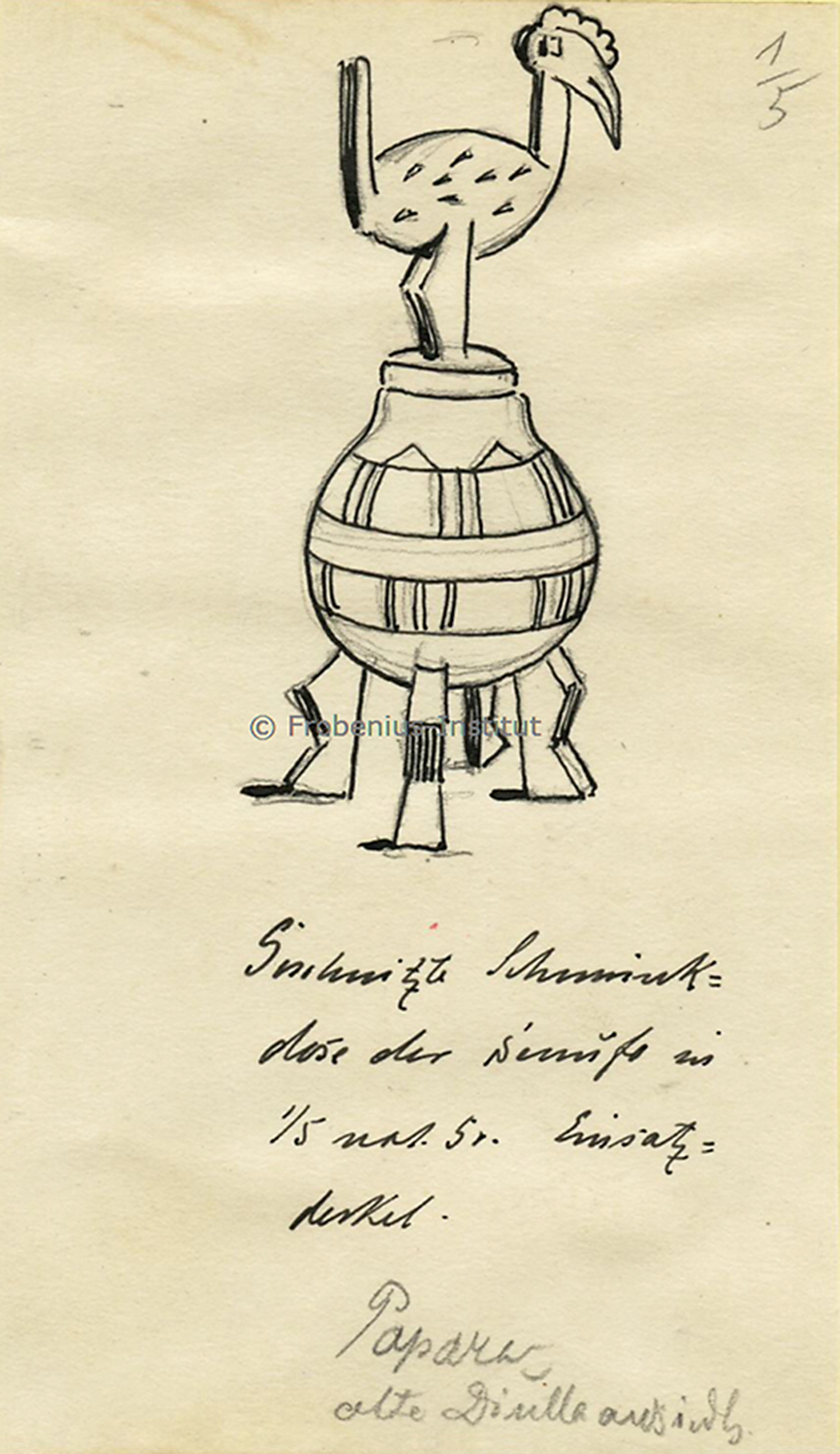

Records from the German Inner-African Research Expedition [Deutsche Inner-Afrikanische Forschungs-Expedition] that German traveler, collector, and ethnologist Leo Frobenius led through West Africa from 1907–1909 provide additional depth to our knowledge of arts from the three-corner region. Few European or North American scholars who have published on three-corner-region arts have examined documents from the early-twentieth-century expedition, a mission that is contemporaneous with Delafosse’s efforts to define the parameters of a Senufo country. When we compare information that members of Frobenius’s team recorded with other writings about communities and arts regarded as Senufo, we find unanticipated resonances and discrepancies. Notes and images identified with the 1907–1909 expedition currently reside at the Frobenius-Institut für kulturanthropologische Forschung an der Goethe-Universität in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Several illustrations in the collection depict objects that formally resemble works Goldwater included in his 1963 show.Footnote 48 For example, one drawing presents a staff topped with a seated female figure (Fig. 5). An annotation in darker ink on the illustration reads, “Papara. Diulla [Jula] in area of Furru [probably Fourou, Mali].” Senufo written more lightly on the paper’s edge suggests a different label. A gloss accompanying another drawing of a lidded vessel reads, “Carved paint box of the Senufo in 1/5 of actual size. Insert cover.” The note links the object to “the Senufo” (Fig. 6). Yet lighter writing in pencil offers, “Papara – old Diulla settlement,” suggesting the vessel may also have some connection to a “Diulla,” probably Jula, neighborhood. The annotations on the two images appear to deliver conflicting information about the objects’ status as Senufo or Jula.Footnote 49 Documentation related to the 1907–1909 expedition also suggests that members of the team already had ideas about the kinds of objects that constituted Senufo arts. The finding captures our attention because it undermines the idea that Europeans began defining parameters of a Senufo style or recognizing objects as Senufo in the 1930s.Footnote 50 When French colonial administrator Delafosse published the two installments of his article on populations he classified as Senufo in 1908 and 1909, he included a few hand-drawn illustrations of objects that do not fit within understandings of a style that art enthusiasts regarded as a core Senufo style later in the twentieth century. But in a notebook from the early-twentieth-century expedition signed by engineer Reinhard Hugershoff, the member of Frobenius’s team indicates he expected to see certain forms in places he regarded as Senufo. The engineer explains, “Wooden masks I have not discovered anywhere in the area, at least not such as are really identifiable as Senuffo-works.” The statement suggests that Hugershoff had previously seen actual wooden face masks or helmet masks that someone had designated as Senufo or images of such objects. Hugershoff continues, “On the other hand, one finds rattles for the circumcision festivities (wosamba) with horsehead-like carving, and flanges [probably heddle pulleys] from the looms with original heads.” Thus, at least some of Hugershoff’s findings seemed to correspond with what he imagined he would see.

Figure 5. Illustration of a wooden staff with “Papara. Diulla [Jula] in area of Furru [probably Fourou, Mali]” written in an annotation. Ink drawing on paper possibly by Reinhard Hugershoff, 12.7 × 16.8 cm. Frobenius-Institut für kulturanthropologische Forschung an der Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt am Main, KBA 10416.

Figure 6. Illustration of a lidded container with annotations that read “Carved paint box of the Senufo in 1/5 of actual size. Insert cover” and “Papara – old Diulla settlement.” Ink drawing on paper possibly by Leo Frobenius; 7.7 × 12.7 cm. Frobenius-Institut für kulturanthropologische Forschung an der Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt am Main, KBA 04237.

As we have seen, some illustrations of objects from the expedition match later twentieth-century ideas about a core Senufo style even if classificatory terms on the drawings raise the possibility of different attributions. The information from the early-twentieth-century expedition further intrigues when we consider that members of the expedition apparently did not travel to Korhogo, the city that Delafosse and many subsequent observers have regarded as the center of Senufo-ness. Hugershoff does note geographic differences in the production of objects. He writes, “The native carpentry and woodcraft, in the whole northern part of the region and in Sikasso, is quite primitive, even though now and again original forms make an appearance.” He adds, “In general, a development of woodcarving is unmistakable towards the south, compare the small wooden figures and pot-like lidded vessels with figures, to the south of Furu [Fourou].”Footnote 51 Hugershoff may or may not have had the previously mentioned vessel in mind when he referred in his notebook to pot-like lidded vessels with figures to the south of Fourou. We are finding that our examinations of additional documentation complicate rather than corroborate prior knowledge of Senufo-labeled arts.

Scales of Analysis

Our study of notes and drawings from the 1907–1909 expedition has further led us to assert that the concept of scale offers a useful frame for thinking about historical analysis as well as the disparate perspectives and fragmentary evidence upon which analysis relies. Art historians as well as scholars situated within other disciplines often think in terms of scale. Focused primarily on the concept of scale in the making and experience of art and architecture, especially in Inca contexts, art historian Andrew James Hamilton emphasizes scale as relational and not absolute. He further underscores the relative and subjective dimensions of the concept.Footnote 52

Scale shapes thinking about digital humanities. In an essay on productive possibilities for joining computational approaches with art-historical inquiry, art and architectural historian Paul Jaskot argues that “digital methods favor large scalable questions that require big data.”Footnote 53 Jaskot focuses on what he calls the “scale of evidence” and highlights potential in study of “thousands or even millions” of images or other records.Footnote 54 Computers certainly enable scholars to analyze enormous numbers of records. The approach hinges on construction of databases, an intellectual activity too often viewed as mere data entry.Footnote 55 But the idea that “big data” are a requirement for significant computational analysis in the humanities or in any other area of inquiry unsettles given longstanding disparities in the recording and digitization of information. Fields of inquiry as well as institutions that historically have benefitted from greater resources may have more “big data” sets ripe for digital analysis. If scholars insist on “big data” as a prerequisite for digital scholarship, then they risk promoting and exacerbating power-based inequalities at odds with conceptions of digital humanities as a means for addressing structural problems and democratizing knowledge production.Footnote 56

When we began working on Mapping Senufo, we estimated that we might locate hundreds of Senufo-labeled objects with specific place-based information attached to them. Members of the project team devoted significant thought and energy during the first several years of the project’s development to creation of a relational database. Digital scholarship specialists Joanna Mundy and Sara Palmer worked with us to design a database for the project that accommodates geographic data linked to objects as well as other details we have sought to organize and trace.Footnote 57 Uncertainties that became apparent as members of the team worked on building the database and analyzing the first large set of data entered into it plunged us into discussions of evidence at the micro rather than macro level.Footnote 58 Thus, our use of computational methods led us away from “big data.”

As we continue to work on Mapping Senufo, we have found the cartographic concept of scale especially helpful for assessing different approaches to understanding cultural and historical phenomena. In How to Lie with Maps, geographer Mark Monmonier examines how key elements of maps – scale, projection, and symbolization – serve as sources for misinterpretation.Footnote 59 A cartographic scale shows the size of a feature on a map compared to the feature’s actual size on earth. A map with a larger scale created on a single sheet of paper covers a smaller proportion of the Earth’s surface than a map with smaller scale produced on the same size paper does. Consequently, a map’s scale makes possible or denies a cartographer’s inclusion of certain details in a geographic rendering.

An observer working at a larger scale may cover less geographic area in a study but document more specific details about particular places and individual people operating within them. By contrast, a person working at a smaller scale may cover more geographic area and see broader features. Each scale facilitates understanding of geographic space, but disparate concerns require maps at different scales to generate productive insights. A map reader must remain attentive to each map’s scale in order to calibrate questions with regard to each particular scale and to consider different maps, and thus their divergent scales, in relation to each other. Historians and other scholars have debated the relative merits of splitters and lumpers, terms that refer respectively to thinkers who work at larger and smaller scales.Footnote 60 We have found that framing discussion in terms of scales of analysis instead of in terms of splitters and lumpers enables one to see more clearly how various perspectives reveal different aspects of the same phenomenon and thus interrelate rather than compete with each other.

A comparison of illustrations and notes produced as part of the 1907–1909 expedition with Gagliardi’s field-based research nearly a century later demonstrates how observers may operate at different scales and how findings may vary as a result.Footnote 61 Communities identified as Senufo and referenced in the notes from 1907–1909 are located a few hundred miles west of the communities of western Burkina Faso where Gagliardi based her own research. Each set of data shows how the term Senufo is applied to certain arts that Goldwater and other twentieth-century art enthusiasts have not commonly labeled as Senufo. Each observer also sought differing amounts of detail depending on the observer’s scale of analysis.

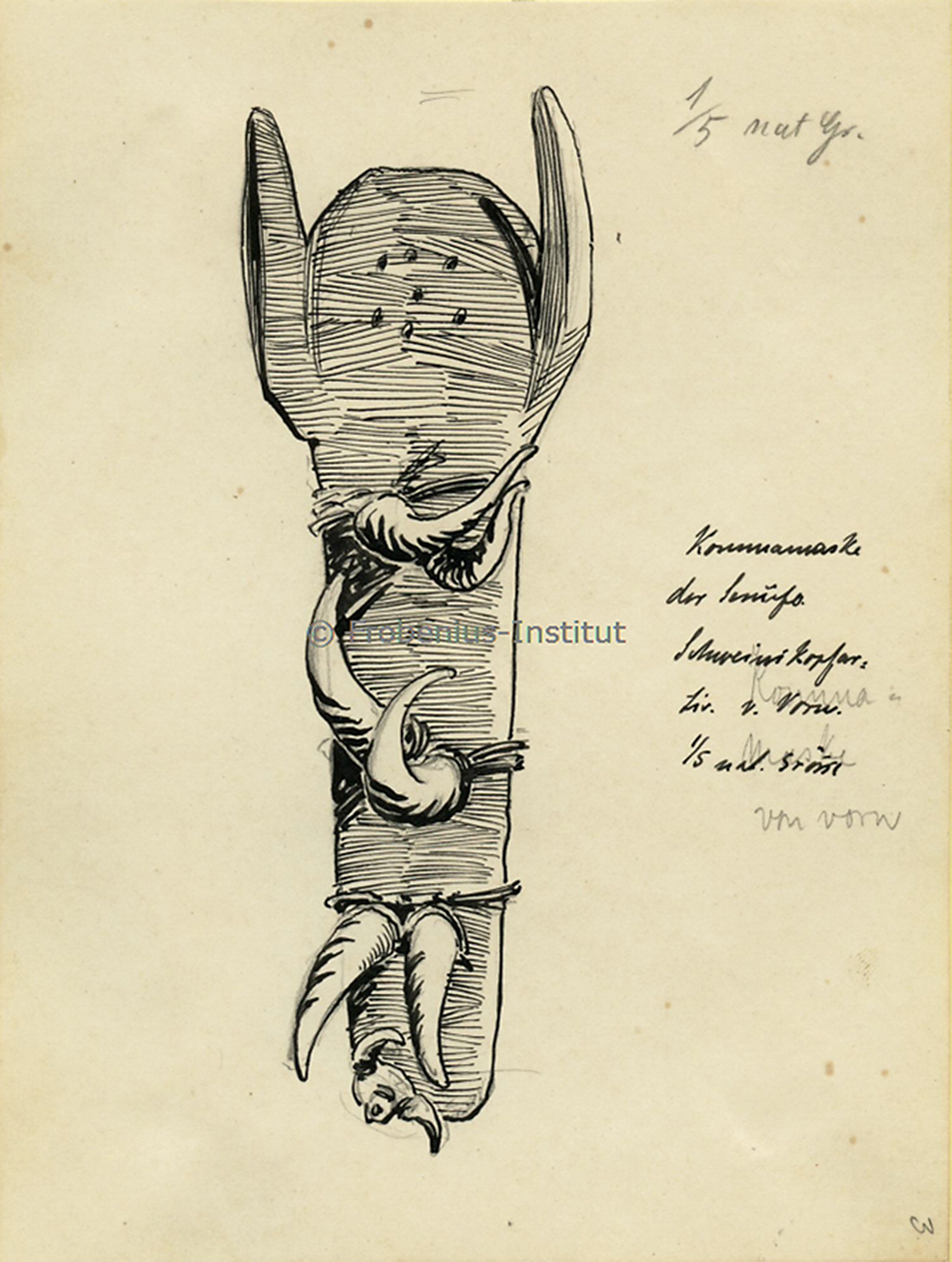

An illustration from the early-twentieth-century expedition shows a helmet mask. A handwritten gloss accompanying the image describes the object as “Mask of Komma of the Senufo, Pig’s Head” (Fig. 7). Komma [Koma], likely another name for Komo, designates a power association in and beyond the three-corner region. Power associations work to effect change in people’s lives through the association leaders’ guarded knowledge of potent matter and intangible energies. The organizations’ leaders heal, but they also have the capacity to cause harm. Power associations have served as the great patrons for the arts in western West Africa since at least the nineteenth century, when European travelers began collecting and documenting the organizations’ arts. The organizations invest in and maintain accumulative sculptures and installations, and they stage vibrant performances.Footnote 62

Figure 7. Illustration of a helmet mask with an annotation that reads “Mask of Komma [probably Komo] of the Senufo, Pig’s Head.” Ink drawing on paper by an unidentified artist; 12.7 × 16.7 cm. Frobenius-Institut für kulturanthropologische Forschung an der Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt am Main, KBA 10183.

When Goldwater organized Antelopes and Queens: Bambara Sculpture from the Western Sudan at the MPA in 1960, he included in the show arts attributed to Komo and other similar organizations, including Kono. Other scholars and art enthusiasts at the time identified Komo, Kono, and other power associations as distinctly Bamana or Mande institutions, with Mande serving as an umbrella term for a larger group that includes the Bamana group but not the Senufo group. The scholars and art enthusiasts considered Komo and Kono helmet masks as Bamana, a category of arts they viewed as separate from arts they labeled as Senufo. But the gloss accompanying the drawing of a Komo helmet mask from the 1907–1909 expedition links the object to “the Senufo.”

Hugershoff’s notebook entitled “The Senufo” makes additional references to Komo and Kono.Footnote 63 Even if notes from the expedition specify that Komo’s presence in Senufo communities was rare, Hugerhoff’s writings signal that communities Europeans regarded as Senufo in the early twentieth century did at times support the organization. Other sources from the late nineteenth century to the present refer to Komo and other power associations in communities that observers recognized as Senufo, thus further indicating that clear-cut characterizations of the organizations as specific to Bamana or Mande cultural or ethnic groups separate from a Senufo cultural or ethnic group are difficult to maintain.Footnote 64 A chapter of Mapping Senufo devoted to the 1907–1909 expedition will include information about Komo and Kono to show that the associations have at times fallen within the Senufo rubric.

While European and North American observers have noted the existence of power associations in the three-corner region and recorded information about their activities for more than a century, we unfortunately have few detailed histories specific to particular locales. But lack of documentation does not necessarily signal the unimportance of local-level histories to the communities that have supported or continue to support the organizations. A return to earlier sources and explications in an effort to recover details requires careful attention to the scales of analysis each observer or researcher employed. A particular observer’s scale of analysis could not match a contemporary researcher’s scale of analysis, and a contemporary researcher may never be able to access records to make possible recovery of exact details of local agency or examination of specific local histories. Still, we can look for references to specific individuals or histories, however cursory references may be, and we can develop language in our presentations to acknowledge the considerable gaps between what we would like to know and what sources we have consulted allow us to know. As we develop Mapping Senufo, we are working to recognize such local-level histories even if we have not yet been able to uncover details and to develop language that foregrounds knowledge gaps rather than glossing over them.

Statements about power associations in the notes from the 1907–1909 expedition we have consulted are often broad. For example, the writer of one notebook, probably Hugershoff, asserts that “Kono … is the first well-preserved secret association…It is considered weaker than the [Nya] society. But that is not to say that it is older or younger than this institution.”Footnote 65 Based on the comments the author committed to paper, we cannot know if the statement reflects information he gathered from people in the three-corner region about distinct association chapters in a single location or the institutions in a particular area or the institutions more generally. While we search for additional details to help us better understand the assertion, we view the statement as a clue that when combined with other information, may direct us to greater insight in the future.

Other documentation from the expedition yields specific instead of general information that we will highlight in Mapping Senufo. Drawings of power association houses include glosses with place names (Figs. 8 and 9). We can imagine that the illustrator, again probably Hugershoff, appears to have seen a Kono house similar to one shown in a drawing located to the town of “Kadjoro” (probably Katiolo) in July 1908, and another Kono house similar to the one shown in another drawing located to the town of “Lubugule” (probably Lobougoula) during the same month.Footnote 66 Unfortunately, documentation from the expedition we have consulted provides no information about who the leaders of the Kono chapters in “Kadjoro” and “Lubugule” were in July 1908, how they acquired their knowledge, or who their collaborators, rivals, or clients were. In order to recover local agency, we would need records from a local community member or another observer who worked within a larger scale of analysis and documented more details within a more confined geographic area. We would then need to assess the information within specific local economic, interpersonal, and political contexts.

Figure 8. “Konohütte zu Kadjoro [Kono Hut of Kadjoro],” shown at 2.5 meters in height and classified as Senufo in the Frobenius-Institut database. Ink drawing on paper by Reinhard Hugershoff, dated probably 1908; 21.5 × 15 cm. Frobenius-Institut für kulturanthropologische Forschung an der Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt am Main, EBA-B 00232.

Figure 9. “Kono zu Lubugule [Kono of Lobougoula],” described as 3 meters in diameter and classified as Senufo in the Frobenius-Institut database. Ink drawing on paper by Reinhard Hugershoff, dated probably 1908; 21.5 × 15 cm. Frobenius-Institut für kulturanthropologische Forschung an der Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt am Main, EBA-B 00233.

Older and more recent accounts of power associations lead us to infer that between 1907 and 1909, the specificity of individual chapters of the organizations and their leaders mattered. Since 2004, Gagliardi has spent nearly 22 months in western Burkina Faso, where she has interviewed power association leaders and other specialists. Her field-based research shows that power association leaders compete for status and authority and that they leverage the arts to distinguish themselves from their colleagues and competitors. Within a town and from town to town, specialists compete with each other for clients and prestige. An action one specialist considers aggressive, another may consider defensive.

People Gagliardi interviewed frequently described contests between or among specialists. Several people explicitly recalled the deadly August 1986 contest between two men who had worked together closely in conjunction with a Komo chapter in the town of Sokouraba. People said the close collaboration led to jealousy because one man earned a reputation that surpassed that of the other. Armed with knowledge of his colleague’s skill, the man of lesser renown reportedly hurled an invisible missile at his more distinguished colleague. The Komo leader of greater fame died, but, before he did, he reportedly retaliated with another lethal invisible missile. His former collaborator-turned-rival also died. The smaller scale of analysis prevalent in documentation from the 1907–1909 expedition does not permit us to pinpoint such exact stories people may have told at the time. Perhaps the early-twentieth-century documenters on Frobenius’s team did not find such particulars important. But the absence may not mean the details were unimportant to people in and around “Kadjoro,” “Lubugule,” or the other towns visited by at least one member of the expedition team. In Mapping Senufo, we will urge readers to consider how observers may at times overlook details they are not primed to see as significant.

Documentation from the 1907–1909 expedition allows only a few glimpses into the knowledge and activities of power association leaders. However, certain information in the early-twentieth-century records resonate with reports of other observers. For example, notes from the German team hint at knowledge of plants promoted by power associations. In a section of notes dedicated to the Nya power association, the author, probably Hugershoff, indicates that the organization, by which he may mean each chapter, maintains “three pouches filled with medicines.”Footnote 67 He explains that a person who joins Nya, “receives some of the medicinal content of the pouches, which allegedly consists of crushed, pulverized tree bark.”Footnote 68 He also highlights the medicine’s protective and poisonous qualities.Footnote 69

Nya, like Komo and Kono, continues to exist in western West Africa, including but not only in communities regarded as Senufo, and knowledge of plants remains important to the organizations’ activities. When French photographer Agnès Pataux visited a Nya specialist in Mali in 2006, she photographed him with three bags. Pataux interviewed a Nya leader in another town the following year. He referred to three bags filled with objects created from the roots of certain trees.Footnote 70 Indeed, plant knowledge has appeared for more than a century as a central feature of power associations in documentation of the organizations’ activities.Footnote 71 Power association leaders develop expert knowledge of plants, and vegetal matter constitutes some of the most important material incorporated into their objects.

Members of the German expedition in the early twentieth century and Gagliardi, who conducted research in a different area almost a century later, appear to have relied on different scales of analysis. Scholars operating at the same moment may also favor different scales. The collaborative nature of our project has forced the two of us to grapple with our different proclivities toward emphasizing broad views or specific details in our solo studies and presentations of African arts. In addition, our intellectual partnership has required us to wrestle with our disparate intellectual genealogies, professional investments, and personal attachments. We repeatedly find that we must negotiate our different points of view and understandings as we develop the project. The experience further contributes to our recognition that any knowledge is partial and contingent.

Our efforts to bring together our own overlapping, but at times, conflicting, perspectives within a single publication have led us to realize through experience that no single position captures a full view and that we cannot always reconcile our disparate viewpoints. The realizations have ceased to exist merely as theoretical statements about the partiality of any knowledge production. We have had to think about how to manifest our divergent understandings in our research and writing practices. Our different emphases also inform our intentions to reimagine the form of a born-digital scholarly publication designed to engage scholars, as well as broader audiences. We seek to create a publication that through its very form argues against a single, narrative account of what Senufo arts are or what they mean.

Reimagining a Digital Monograph

In the final form of Mapping Senufo, we will aim to direct readers to various firsthand accounts and lead them to arrive at their own conclusions. We will invite readers to look closely at extant evidence as well as details the sources provide, silences the documents elide, and questions they evoke. For instance, an interactive section of Mapping Senufo that the project team is currently designing will further remind readers that photographs are not neutral documents. They and metadata about them present partial accounts (Figs. 10 and 11).Footnote 72

Figure 10. Mark Addison Smith. Page showing a possible design that combines hand-rendered text with images created after photographs in the Michel Convers photographic collection now at the musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac in Paris, from Mood Boards + Design Experiments for Mapping Senufo, 31 January 2020.

Figure 11. Mark Addison Smith. Page showing a hand-rendered drawing after a photograph from the Michel Convers photographic collection now at the musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac in Paris, from Mood Boards + Design Experiments for Mapping Senufo, 31 January 2020.

A digital monograph creates opportunities to demonstrate the contradictory nature of select observers’ documentation and other enthusiasts’ analyses of arts identified as Senufo through interactive features. Our goal is to show and investigate fragmentary and divergent details instead of weaving together disparate perspectives and information in order to present a singular, authoritative view. Our vision departs from common practices for realizing scholarly monographs.Footnote 73 Rather than attempt to account for every perspective past and present as if such an approach were even possible, we will focus on people who have repeatedly garnered recognition for contributing to the shaping of the corpus or knowledge about it. The records we have are lopsided. Unfortunately, many Europeans and North Americans who traveled to the three-corner region in the twentieth century and wrote about Senufo arts did not record the names of specific people in the area with whom they interacted. European and North American names dominate many publications and records. Yet the people whose names do not appear on paper were still integral to shaping the corpus and stories told about it. We will thus seek to draw attention to lost voices and perspectives.

Enacting the Argument

The interactivity of digital environments makes it possible to render readers active participants in their own knowledge construction and experience different modes of argumentation. As digital publication specialist and scholar of rhetoric Cheryl E. Ball asserts, multimodal formats support nonlinear arguments presented as “a persuasion, a juxtaposition of modal elements from which readers infer meaning.”Footnote 74 Readers of our digital monograph will isolate and investigate particular objects, people, places, and events integral to the ongoing recognition of a single corpus of art as Senufo and also create connections among elements. Through this process, readers will become authors of their own contingent understandings, enacting our argument that a category of art and knowledge about it are always circumstantial and incomplete.

As we currently conceive it, the final version of Mapping Senufo will feature image- and text-based sections that present readers with disparate, uneven, and often irreconcilable documentation from various observers who recorded information about Senufo arts in different places and at particular moments. It will demonstrate to readers the fragmentary nature of any record. For example, a reader who considers Goldwater’s analyses alongside documentation from the 1907–1909 expedition may see productive differences in thinking about Senufo arts and identity. When Goldwater published photographs of a staff topped with a seated female figure then in the collection of Eric Peters of New York, Goldwater attributed the object to the central region based on his evaluation of the object’s style (Fig. 12). Goldwater provided no other information to support the attribution.Footnote 75 He located two other staffs illustrated in his book on Senufo arts to the northern region and more specifically to the Sikasso district.Footnote 76 A look at illustrations from the 1907–1909 expedition that Goldwater does not clearly cite, thus suggesting he may never have consulted them, complicates Goldwater’s assessments of form as well as assumptions undergirding his conclusions. The early-twentieth-century drawings show staffs located to the Sikasso region. The forms in the illustrations appear quite different from the objects Goldwater identifies with Sikasso and its environs. The comparison may prompt a reader to interrogate evidence available for linking historical arts of Africa to more or less circumscribed geographic areas. Or it may generate other inquiries or determinations we cannot anticipate.

Figure 12. Unrecorded maker. Detail of staff. Wood, iron, reptile skin, h. 139 cm. Mercedes and David Serra Collection, Barcelona. Photo © Galeria David Serra.

Another reader may select a different point of entry into the monograph. A reader interested in sculptures linked to the town of Lataha might choose to follow a visual essay, clicking through a series of frames that combine images and minimal text to probe the extent of extant evidence as well as limitations of that evidence. Or a reader might decide to devote attention to a textual essay on the topic of mid-twentieth-century photographs of objects standing in a clearing, presumably in Lataha. The visual and textual essays will stand alone, but they will also cross-reference and complement each other. Other visual and textual essays in the digital monograph will address other objects, people, places, and events related to the construction of present-day knowledge of Senufo-labeled arts. Readers will pick and choose what to view and read, creating and revising their understandings as they make additional choices.

Performative, nonlinear modes of argumentation have featured in the generation and circulation of art-historical knowledge in Europe and North America since the late nineteenth century in the form of the slide lecture.Footnote 77 Art historian and digital humanist Alison Langmead reflects on the discipline’s history and argues that the “engaged performance rather than … recitation of a linear, written text” common to slide lectures “can find an easy home in, and a deep connection to, the world of digital interactivity.”Footnote 78 Digital technologies grant scholars opportunities to experiment with performative, nonlinear possibilities for producing and sharing knowledge. We are working with project team members to realize this potential.

In addition, the nonlinear, embodied mode of presentation we are developing in Mapping Senufo parallels aspects of knowledge transmission prevalent in the three-corner region. As Burkina-born scholar Ibrahim Traoré Banakourou explained, his elders in Burkina Faso and Mali instructed him in local knowledge.Footnote 79 Rather than articulating clear arguments at the outset of a lesson and supplying evidence to support their assertions, the elders often presented the younger learner with riddles, directed him to certain evidence, and allowed him to arrive at his own conclusions. The approaches to learning and knowing that Traoré described, like the publication design our project team is developing, encourages investigation. It also emphasizes the time-based and subjective nature of knowledge acquisition. As we continue to work on the design for Mapping Senufo, we remain committed to developing deeper understanding of forms of knowledge production and dissemination in the three-corner region and to drawing upon them in the digital monograph.

Expanding the Audience

The online accessibility of digital publications raises the possibility of engaging larger audiences. In their introduction to Debates in Digital Humanities 2019, Matthew K. Gold and Lauren F. Klein argue that current scholars positioned within the field of digital humanities endeavor to extend their intellectual work beyond the confines of the academy. Gold and Klein also insist upon an urgent need to marshal digital tools and methods in order to examine power structures in wide-ranging contexts and to involve broad publics in exchanges with scholars.Footnote 80 We similarly seek to identify and investigate power structures in the circulation of and knowledge about Senufo-labeled arts throughout the twentieth century, and we also aim to reach a variety of readers. We have already discussed the project with scholars based in universities and museums as well as with people in other positions in Africa, Europe, and North America.Footnote 81

Our ambitions to make knowledge about African arts and history accessible to diverse scholarly and non-scholarly audiences find precedent in exhibitions within the field of African art history. Exhibitions produced in the 1980s and 1990s nourished scholarship within the field and continue to serve as touchstones for analyses. The same exhibitions also demonstrated that groundbreaking intellectual work can captivate museum-going publics without specialized knowledge of a topic as well as endure for future scholarly engagement through publications created in conjunction with the shows.Footnote 82 As we develop Mapping Senufo, we return to models for public scholarship within and beyond our field. We also benefit from project team members who have not previously studied Senufo-labeled arts specifically or historical arts of Africa more generally and who caution us if we become mired in details that seem uninteresting or insignificant to curious but previously uninformed audiences.

Our aims further reflect separate, longstanding commitments to public scholarship and histories of knowledge production in public fora.Footnote 83 As a university-based scholar, Gagliardi has continually sought to develop ways of writing about her research that communicate nuanced information and complicated concepts in clear language comprehensible to academic and non-academic audiences. She eschews the notion that her first-year undergraduate students or any other non-specialist crowd cannot grasp subtleties or intricacies.Footnote 84 And in projects he pursues as a museum-based scholar and curator, Petridis installs objects within three-dimensional spaces as well as develops content about the works designed to attract general publics and offer informed insights. We bring the same concerns to the development of Mapping Senufo.

While our in-progress, born-digital publication project centers on a single corpus of art located to West Africa and knowledge about it, our efforts address a more fundamental and urgent present-day concern, namely how people evaluate evidence and present findings. We seek to assess the nature of evidence for making certain claims and to invite readers to think about how any of us knows what we know. The imperative to attend to the nature of evidence, whether verbal or visual, reflects more than academic pursuits.

As studies published by Stanford History Education Group in 2016 and 2019 show, students in American middle schools, high schools, and universities, including students at the nation’s top universities, lack the ability to distinguish credible information from unreliable assertions presented online.Footnote 85 The group implores action. While scholars must remain attentive to the sources we use and advance knowledge, we must also find alternate modes for presenting our findings to different publics if we want to try to address an alarming trend in how people assess information in the digital age. As the project team works on the design of Mapping Senufo, we endeavor to use digital tools and methods in order to help combat a problem proliferating in the digital realm. We are creating a born-digital, open-access scholarly publication to invite readers from within and beyond the academy to think more critically about how we know what we know.

Conclusion

While Vansina, Hart, and MacGaffey have asserted that studies of so-called historical or classical African arts have often lacked reliable data to support interpretations, scholars of African arts need not settle for speculation. Our efforts to use digital methods led us to reconsider familiar claims, parse disparate sources, and fracture all-encompassing accounts in ways we had not previously. As we worked with the project team to create a multilayered digital map and underlying relational database, we determined we needed to evaluate the quality and character of our data instead of confirming locations for which evidence about the places and their links to particular objects seemed vague. Possible conclusions that followed from the assignment of a place name to an object also varied in their potential to yield significant insights into the making, meaning, circulation, or use of an object. The at times overlapping and at times incongruous nature of our individual understandings further led the two of us and the entire project team to reflect on the subjectivity inherent in knowledge production as well as the different scales of analysis observers apply to their pursuits.

We concluded that the interactivity of digital environments offers novel opportunities to reimagine the form of a scholarly monograph using alternate modes of argumentation. Through the final, version-of-record instance of Mapping Senufo, we will demonstrate the subjective nature of knowledge. We will present underlying structures and reveal gaps. We will invite readers to investigate their own questions and arrive at their own conclusions. The form of the publication itself will manifest our argument. We are also working with the project team to design a born-digital, open-access publication that will engage broad audiences as well as respond to a pressing need to foster more robust skepticism about any claim and the evidence used to support it.