Crosby Hall, all that remains of the magnificent fifteenth-century Crosby Place, stands today in Cheyne Walk, a long way from its original location in commercial Bishopsgate. For all that it exhibits an air of authenticity, this is carefully crafted: little of the original building, which is largely hidden by the accretions of nineteenth- and twentieth-century restorations, has been left intact. Yet despite the substantial sums that have been invested in its renovation in recent years, its reputation as what Simon Thurley describes as ‘the most important surviving secular domestic medieval building in London’ is not widely known.Footnote 1 In the nineteenth century, however, it was renowned in precisely those terms: as one of the finest specimens of medieval domestic architecture in London and a rare survival of the Great Fire that had destroyed so much of the city's historic core. Despite the free hand that has been taken in restoring and improving the building since the nineteenth century, it is an extraordinary survival. Its continued existence, against the odds, into the twenty-first century has been dependent upon the building's historical resonances for both national and local history, and the opportunities it has offered for contemporaries to project onto it their own conceptions of the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, when it was in the heyday of its magnificence.Footnote 2

In the 1830s, Crosby Hall narrowly escaped destruction: as the result of a public campaign it was repaired, restored, and converted into a space to house the Metropolitan Literary and Scientific Institution. This particular history of an early preservation campaign presents the opportunity to analyse the emergence of a discourse of national heritage from the inherited tradition of eighteenth-century antiquarianism and to trace the networks that sustained proactive attempts to preserve the nation's monuments and antiquities. Since the later eighteenth century, there had been gathering awareness of and appreciation for the historic value as well as the aesthetic qualities of ‘architectural antiquities’. Antiquaries such as Richard Gough and John Carter documented such buildings in weighty antiquarian publications and used the pages of the Gentleman's Magazine to inveigh against modern depredations and innovations and to make the case for their preservation.Footnote 3 As early as the 1770s, calls were being made for the government to intervene in the preservation of historic buildings.Footnote 4 By the 1830s, such exhortation was becoming much more frequent, and the British government was compared unfavourably to France where a General Inspector of Historical Monuments had been appointed in 1830 and the Commission des monuments historiques would be created in 1837.Footnote 5 In 1832, for example, John Britton wrote to the Gentleman's Magazine calling for the creation of a society to be called ‘The Guardian of Antiquities’, the remit of which would be to guard against further damage and destruction of historic buildings and to assist legal authorities in their protection.Footnote 6 Such concerns were, in part, the motivation behind the founding of the British Archaeological Association in 1844, the purpose of which was summarized as the ‘discovery, illustration, and conservation of our ancient national monuments’.Footnote 7 They were also responsible for inspiring the actions of those who ensured the survival of Crosby Hall.

Histories of preservation movements and heritage, however, tend to start with John Ruskin or William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: while earlier antecedents are noted, they are seldom evaluated upon their own terms, but are rather seen as anticipatory precursors to the later movement.Footnote 8 Astrid Swenson's recent study The rise of heritage emphasizes the importance of the period 1830–70 for debates about the role of the state in the protection of the past; the establishment of history as academic discipline; the successful restoration of ‘lost’ historical monuments; and the emergence of a popular culture of heritage. But the main focus of her transnational study is on the latter part of her period and on national bodies. Specific examples of action taken on behalf of the preservation and restoration of buildings in the first half of the century are not discussed in any detail. Chris Miele's work on nineteenth-century preservationism identified a number of campaigns or groups formed to preserve buildings in the first half of the nineteenth century but their activities and their roots in eighteenth-century antiquarian sensibilities have never been studied.Footnote 9 Similarly, whilst the literature on antiquarianism, archaeology, and engagement with the past through material objects has increased rapidly in recent years, in terms of more specific studies of attitudes to restoration and preservation, the focus in the first half of the nineteenth century tends still to be upon the ecclesiastical fabric and a movement driven by piety and religious revival, rather than the fate of secular buildings whose value derived from their association with a national and domestic past.Footnote 10

The case of Crosby Hall highlights how the development of antiquarian and historical scholarship in the realm of domestic and secular antiquities from the eighteenth century onwards combined with narratives of national historical development, focusing upon the contributions of urban and commercial life to modern progress, to bring hitherto unregarded buildings into the limelight.Footnote 11 Its fate is indicative of a trend towards a more inclusive sense of the nation's architectural heritage than that of the eighteenth century which tended to focus upon the high profile buildings of church and state, and it reflects a growing interest in the historic fabric of London (and other cities) that can be evidenced in a wide range of publications devoted to London's buildings and to its history. It is important to remember, however, that Crosby Hall is a rare survival: most historic buildings which stood in the way of improvement and modernization were pulled down. Unsurprisingly, the campaigners of the 1830s and of the early twentieth century, when the Hall was threatened with demolition again, faced an uphill struggle in convincing a wider public of its value and in persuading them to pledge their financial support. The reasons for their success demand interrogation: the visibility of the Hall's location in the heart of the City of London, the tight network of activists, and the high profile of those whose support was solicited and lent for the campaign were all clearly critical. The agency of particular individuals, notably Maria Hackett, discussed below, was also crucial. But overall success hinged upon the Preservation Committee's timely representation of Crosby Hall as a building that was emblematic of London's history and their appeal to the period's burgeoning interest in the late medieval and Tudor era as one that was crucially formative in national life.

I

Crosby Hall has been a London landmark, ever since the wealthy wool merchant and grocer, Sir John Crosby, acquired the lease of a plot of land from the Italian merchant Cataneo Pinelli in 1466 to build himself a townhouse to rank with the urban residences of the aristocracy. Describing the house in Bishopsgate in 1598, John Stow observed that ‘This house he built of stone and timber, verie large and beautiful and the highest at the time in London.’Footnote 12 By the end of the seventeenth century, however, when publications descriptive of London started to increase, Crosby Place was no longer the distinguished residence it once was.Footnote 13 As early as the 1620s, it had reportedly become much decayed and repairs were ordered to be put in hand. By the 1640s, it was being used as a royalist prison. Although it escaped the Great Fire of 1666, a separate conflagration a few years later destroyed all but the Great Hall and the north wing (the rooms that would later be known as the Council Chamber and the Throne Room). Much of the original fabric was demolished and new houses were erected in its place to form Crosby Square. From 1672, the Great Hall was leased to a Presbyterian congregation for use as a meeting house, for which purpose a floor was inserted, splitting the space in two, with the downstairs retained as a warehouse. Meanwhile, the rooms in the north wing were separately leased and were used as a warehouse by the East India Company. In Ogilby and Morgan's map of 1677, the site was prosaically listed as the General Post Office.Footnote 14

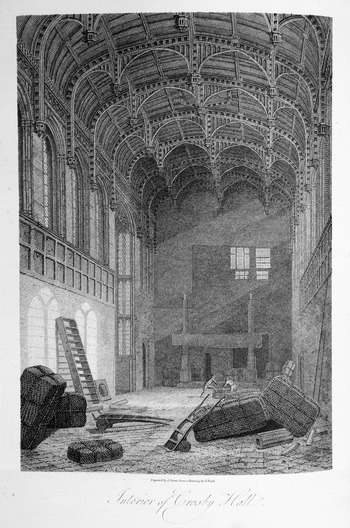

Ignominious decline through neglect and misuse continued throughout the eighteenth century. In William Maitland's History of London (1739) the ‘spacious, lofty and magnificent edifice’ was tellingly referred to in the past tense as having ‘anciently stood’ in Crosby Square. By 1766, it was simply commemorated as ‘a very large house, built by Sir John Crosby, grocer and woolman, called Crosby Place’.Footnote 15 By 1769, the Presbyterians had left, only to be replaced by a congregation of Rellyanists, followers of the Universalist preacher, James Relly. After his death in 1778, the lease passed to a firm of packers, Holmes and Hall, who inserted a second floor into the Great Hall (see Figure 1). As one of the nineteenth-century campaigners was to note with regret, ‘its magnificent roof [was left] in a mere lumber garret; the ante-room ceiling and Council Chamber floor were broken through for their machinery, and the octangular bay window served for a counting house’ (see Figure 2.)Footnote 16 Little surprise then that those topographers and antiquaries who bothered to update Stow passed over Crosby Square, as the surrounding area was then known, without reference to the house or to Sir John Crosby himself.Footnote 17

Fig. 1. Interior of Crosby Hall showing the inserted floor from the Penny Magazine, 48 (Dec. 1832), p. 385, reproduced by kind permission of Special Collections, University of Leicester.

Fig. 2. The interior of the great bay window from Robert Wilkinson, Londina illustrata (London, 1819), reproduced by kind permission of Special Collections, University of Leicester.

The shift in taste towards the picturesque in the later eighteenth century and the growing popularity of antiquarian and topographical publications, however, opened the way for a re-evaluation. The irregularity, asymmetry, and curious detail associated with gothic and vernacular architecture acquired aesthetic appeal in its own right, enhanced by the imaginative associations and meditative potential inherent in the age and decay of these buildings. Crosby Hall began to attract increased attention, first from topographical artists and, a generation later, from architects of an antiquarian persuasion.Footnote 18 Thomas Pennant was the first to identify the building as a historical curiosity, rather than simply repeating Stow's description. In Of London, first published in 1790, he observed that ‘the hall, miscalled Richard III's chapel, is still very entire; a beautiful gothic building with a bow-window on one side; the roof is timber, and much to be admired’.Footnote 19 The description was illustrated with an engraving of the exterior of the Great Hall by one of the leading antiquarian draughtsmen of the day and gothic enthusiast, John Carter. Pennant's lack of expertise in architectural or gothic antiquities betrayed itself here in his typically perfunctory summary, but his description highlighted three features which would be elaborated upon in much more detail in succeeding years: the association with Richard III, the bow window (or oriel window as it would commonly be referred to in the nineteenth century), and the ornate timber roof in the Great Hall.Footnote 20 Some account of London (the original laconic title was expanded upon in later editions) was a resounding success, and was followed by five subsequent editions and abridged versions. Meanwhile its content was shamelessly plundered and reproduced in the texts of other less compendious volumes aimed at the growing numbers of visitors to London. The publication coincided with a growing fashion for extra-illustration: publishers responded to this trend by commissioning engravings and etchings of scenes, streets, and buildings in London with which collectors might illustrate their volumes, amongst which Crosby Hall regularly featured as a subject.Footnote 21

Storer and Grieg provided the first extended description of Crosby Hall, accompanied by a series of detailed engravings in Select views of London (1804); this was swiftly followed by James Pellar Malcolm's description in Londinium redivivum (1802–7).Footnote 22 Between these two publications, Edward Pugh, writing as David Hughson, included a short and derivative description of the Hall in his 1806 volume on London. Their descriptions have much in common, but would appear to have been written independently. Storer and Grieg and Malcolm were all antiquarian draughtsmen: Malcolm worked extensively for John Nichols, drawing and engraving architectural antiquities for the Gentleman's Magazine and the History of Leicestershire, and Storer was one of the many highly skilled engravers employed by John Britton for his architectural series, including the Cathedral antiquities and Beauties of England and Wales. He also published independently under his own name, including his series of Cathedral antiquities, Select views, and the Antiquarian and topographical cabinet.Footnote 23 Both Storer and Grieg and Malcolm recorded the damage and depredation that had been inflicted – the insertion of additional floors; the losses to the north and south ends of the hall through fire; the injuries sustained by the plasterwork and carved woodwork. They sought also to recreate a sense of the building's original appearance by representing it without the inserted floors in the accompanying engravings (although Storer added some bales and ladders to his representation of the interior of the Hall in a blend of contemporary verisimilitude and antiquarian reconstruction: see Figure 3). Both publications provided much more precise description of the bow window – now referred to as the oriel window – noting the clustered pillars, the depressed arch, and the ornate tracery.Footnote 24 Equally, the carved timber roof was now the focus of detailed attention:

Of the Hall, the first thing which naturally attracts the eye is the roof: this is decorated with a profusion of ornament almost unparalleled, yet disposed with so much taste as not to seem crowded. It is vaulted, forming a sort of flat-pointed arch, which is divided into eight principal compartments by ribs springing from corbels of an octagon form. These compartments, or larger arches, are composed of four smaller ones, from the springs of which depend beautiful drops of pendants, elaborately pierced and carved in a similar manner to those of the roof of Henry the Seventh's chapel at Westminster. The whole of this roof is of oak, and is painted of a stone colour. It is extremely well preserved. The arching of the high slender windows has a general conformity to the roof, and in fact the same conformity is admirably observed throughout the whole building.Footnote 25

Fig. 3. Interior of Crosby Hall from James Storer and John Grieg, Select views of London and its environs (2 vols., London, 1804).

These publications were followed by an article in volume iv of John Britton's influential Architectural antiquities. Britton's account had little to add in terms of descriptive analysis although it did provide a valuable (if sometimes inaccurate) ground plan of the building, before the later alterations. The very fact, however, that the Hall was included in Britton's series is in itself indicative of its developing reputation as a particularly noteworthy example of gothic architecture, a reputation which was reflected in the increasingly detailed attention given to it in other publications on London's antiquities. In 1818, it was the subject of eight plates in Wilkinson's Londina illustrata, engraved from drawings by Frederick Nash. By 1825, A. C. Pugin was referencing the windows, corbels, and roof of Crosby Hall in his Examples of gothic architecture,Footnote 26 while Thomas Allen described it at some length in volume iii of his History and antiquities of London, Westminster and Southwark published in 1828.Footnote 27 Crosby Hall's significance as a specimen of domestic gothic architecture was now firmly established and was already being used as a model by architects such as William Wilkins.Footnote 28 There were consequences, however, to this re-evaluation: the removal by Strickland Freeman (the freeholder) of the stonework and ornamental ceiling from the Council Chamber in 1816 to decorate the dairy at his seat in Buckinghamshire was a serious loss.Footnote 29 Further desecration was suffered as individuals helped themselves to quatrefoils and other ornaments, whose potential value had been greatly increased with the romantic fashion for gothic antiquities as objects for collection and interior decor.Footnote 30 Notably, ornaments from the Council Chamber ended up in the possession of the dealer, Charles Yarnold, from whom they passed into the collection of L. N. Cottingham.Footnote 31

II

In 1829, the lease held by the packing firm Holmes and Hall fell in, and the Freeman family who owned the freehold, having stripped so many of the fittings from the Council Chamber already, advertised the property on a building lease in 1831. The assumption was that the near-derelict hall and related buildings would be demolished to make way for a new development. Unexpectedly, however, its potential destruction provoked dismay and protest: the campaigning antiquary E. J. Carlos wrote an article for the Gentleman's Magazine in December of that year, drawing attention to both its architectural glories and its threatened destruction.Footnote 32 Concern was felt particularly acutely amongst the neighbouring families of Crosby Square and on 8 May 1832 a public meeting was held at the City of London Tavern to establish what was best to be done. The outcome was the establishment of a Preservation Committee to raise a sum sufficient to purchase the lease and to carry out essential repairs in order to save the building. At this stage, it was as yet undecided for what practical purpose it was being saved, beyond the fact that it was of national historic importance and of both aesthetic and antiquarian value.

The initial public meeting was spearheaded by the Capper family of Crosby Square and their family friends: George Capper (a merchant), his nephews Samuel James and John Capper, and Samuel James's brother-in-law, the pottery manufacturer W. T. Copeland, alderman of Bishopsgate ward and later lord mayor of London, who chaired the meeting. Absent from the public meeting, and also subsequent meetings of the committee, was the half-sister of Samuel James and John Capper, Maria Hackett, a redoubtable woman with strong religious, philanthropic, and historical interests who was a driving force behind the campaign from the very beginning and would later play a pivotal role bringing the project to completion.Footnote 33

Hackett's role as a woman is unusual, particularly given the level of financial investment that she committed to the project (see below) and highlights another aspect of women's active engagement with the past in the nineteenth century, as well as the potential for their informal participation in the associations of civil society.Footnote 34 She had a particular interest in the antiquities of London from the Roman era to the present day, corresponding with other antiquaries on Roman, Saxon, and gothic antiquities and in the contribution of women to national life through history.Footnote 35 She is best known today, however, as the ‘Chorister's Friend’ and as a patron of music.Footnote 36 For much of her adult life, she campaigned for the better treatment of choirboys, doing so in terms which were based upon legal issues of rights and the proper use of charitable bequests, rather than simply benevolent sympathy for maltreated boys. Starting with St Paul's, where her nephew was a chorister, Hackett researched the endowments of cathedral choirs and the terms upon which choir schools had been established, highlighting how far cathedral chapters across the country had allowed the original intentions of the benefactors to fall into desuetude.Footnote 37 Hackett's religious faith was clearly the inspirational force in this activity, but hers was a faith that was also imbued with national pride and was closely identified with her own awareness of national history: her Brief account of cathedral and collegiate schools was presented as a contribution to the history of the ‘national church’, to further the ends of the ‘national religion’, and to promote the cause of ‘national education’ [my italics]. Her intervention in the cause of choristers, which originally sprang from close familial connections, was also an intervention in matters of public concern in which she claimed an interest by virtue of her English nationality rather than her sex.Footnote 38 Similarly, her support for Crosby Hall was inspired by personal familiarity with the building, but also her strongly held belief in its importance for the history of London in particular and the nation at large. Possibly, she saw her own activities as part of that tradition of feminine agency in London's history of which she was herself a student.

The Crosby Hall Preservation Committee included Alderman Copeland and the Cappers, and others of their neighbours, but also numbered many leading figures from amongst the architects and antiquaries of the day, including Edward Blore, John Britton, J. C. Buckler, E. J. Carlos, William Etty, Edward Hawkins, A. J. Kempe, John Bowyer Nichols (editor of the Gentleman's Magazine), John Rickman, Anthony Salvin, and William Twopeny.Footnote 39 Several of these individuals, notably Blore, Britton, Carlos, Kempe, and Nichols (as well as Maria Hackett), had already been involved together in recent campaigns on behalf of the restoration of Peterborough Cathedral and for the preservation of the Lady Chapel at St Saviour's Southwark, threatened by new London Bridge, while Etty was a key figure in the preservation of the city walls at York.Footnote 40 A number of members were also regular contributors to John Bowyer Nichols's Gentleman's Magazine, the leading print forum for antiquarian information of the day. The social profile of the Preservation Committee is thus illustrative of the closely knit social and antiquarian networks of the day. Other members of the committee provided valuable ballast and credibility: Maria Hackett would later observe that the support of Sir Robert Inglis and Lord Nugent at the meeting had been crucial to its success. Their presence, she claimed, had given a sanction and éclat to the proceedings and saved the initiative to rescue ‘an old tumble down place that would be much better out of the way’ from being laughed out of court.Footnote 41

A subcommittee negotiated with Williams Freeman and secured the lease of the hall and vaults for £60 with the option of taking the house in Bishopsgate and the Council Chamber in 1836 for a further £90 pa. The committee were particularly anxious to secure the lease of the Council Chamber and the houses at no. 32 and 33 Bishopsgate Street as without these properties it would have been impossible to ensure convenient access to the building. From the start, it was intended that the building should be restored for some practical purpose connected with ‘science, literature and the arts’ and should in the longer term be self-financing. It was not an option simply to preserve the Hall as a picturesque ruin in the centre of commercial London: the restored Hall would have to generate income to cover its expenses. The initial idea was that annual expenditure might be defrayed by converting the Council Chamber to a commercial reading room or library and that the Bishopsgate property might be let as a whole to a bookseller who could use the ground floor as a warehouse, and who would, conveniently, be able to take responsibility for the Hall (which could be hired out for concerts, lectures, and other events) and the library and the collection of annual subscriptions in return for the ‘certain advantages which would result to him in the way of his business’.Footnote 42 Other uses were mooted such as devoting the Hall to a museum of national antiquities, and particularly those that were then regularly being uncovered in London as a consequence of construction work. This proposal was never seriously entertained, but is significant for highlighting the wider agenda of a number of the friends of Crosby Hall who were campaigning for better recognition and protection of domestic antiquities.Footnote 43

In 1833, the Preservation Committee convened in optimistic spirit, confident that the ‘liberality of the public’ would enable them to accomplish their undertaking. In their first report, they stated their aims and objectives:

It is by no means the intention of the Committee to inflict such a reparation on the venerable fabric, as would destroy its character, and give it the appearance of a modern building. It will be their first care to arrest the progress of innovation and decay, by the repair of the external roof, and the removal of all modern and incongruous additions, while every fragment of the original structure will be held sacred. They will afterwards replace such portions of the ornamental carving as have been removed or lost; and will glaze the windows in a style corresponding with the age and character of the edifice, should the amount of subscriptions enable them to carry their designs fully into effect.Footnote 44

The surveyor's report submitted to the Preservation Committee in 1833 must have made sobering reading. The windows and the roof in particular were in need of substantial repair, and the inserted floors and wainscot panelling had to be removed, quite apart from restoring glazing and anything else. The Council Chamber was in an even worse condition with very little of the interior furnishings left intact, the floor in a dire state, and the walls and windows in urgent need of repair and reconstruction.Footnote 45

The first stage was to repair the Great Hall and remove the temporary floors, restoring it to its original admired proportions. The architect Edward Blore agreed to provide his services gratis and Francis Ruddle, who had been employed on restorations at Westminster Abbey and Peterborough Cathedral, was engaged to oversee the building works. The Preservation Committee were fortunate to have secured Blore as architect: having started life as an antiquarian draughtsman he was, by 1832, well established as a leading specialist in gothic architecture, and one whose services were highly sought after.Footnote 46 No doubt he regarded working on Crosby Hall as an opportunity to extend his expertise through close analysis of the building as well as to enhance his own reputation through an act of public spirited benevolence. Another early fillip was received in October 1833 when the fashionable stained glass artist, Thomas Willement, who had recently worked with Blore on Goodrich Court in Herefordshire, responded to one of the fundraising circulars by offering to contribute the glass and glazing for the oriel window.Footnote 47 Clearly, as with Blore, this gave him an opportunity to raise his own profile, but Willement's generosity was also a valuable piece of publicity in its own right and constituted an additional public endorsement of the importance of the project. More prosaically, the suggestion inspired the Preservation Committee to write to the other subscribers inviting them to contribute their own armorial bearings to ornament the windows as a testimony to their own philanthropy.Footnote 48

Maria Hackett's own recollection of the restoration process provides an interesting insight into the practical problems encountered – familiar enough to anyone today who takes on the task of restoring a historic building – and the difficulties of relying upon voluntary contributions and fundraising. The Preservation Committee's efforts met with only limited success: they raised in total around £750, far less than the amounts that contemporary campaigns for buildings such as St Saviour's Southwark, York Minster, Peterborough Cathedral, or even York city walls were raising.Footnote 49 The campaigns to raise money for St Saviour's, York Minster, and Peterborough Cathedral could draw on long traditions of charitable giving for ecclesiastical construction or refurbishment, exploiting the language of piety and religious duty to encourage donations; moreover, cathedrals were amongst the earliest buildings to be identified as part of the nation's heritage.Footnote 50 The success of the York city walls campaign, however, was principally due to the close association of the walls with the city's civic identity and growing awareness that their demolition would be detrimental both to the city's reputation and to its capacity to attract visitors, who were becoming increasingly important to the York economy.Footnote 51

Despite their best endeavours (to be discussed further below), the committee failed to secure major contributions from either wealthy individuals from the City, whom they had evidently hoped might be touched by the building's connections to London's commercial history, or from the various Livery Companies to which Crosby Hall could claim a connection through its owners and tenants. This was a period of increased interest in the history of guilds and of the Livery Companies, driven in part, as their historian William Herbert noted, by anxiety around the ‘Commission for Inquiring into Municipal Corporations’.Footnote 52 This new historical awareness did not, however, extend to sympathy for Crosby Hall. Only the Grocer's Company could be prevailed upon to recognize their connection with Sir John Crosby, a former warden of the Company, with a donation of £100. Nor were the members of the Preservation Committee entirely without blame for this financial shortfall, the minutes clearly indicating that certain individuals failed to pay their own subscriptions.Footnote 53

Meanwhile, plans to put the Hall to more profitable use had failed to secure its long-term future. The intention, as we have seen, had been to equip the internal spaces so that they could be let as shops or as business premises while it was envisaged that the Great Hall should function as a lecture hall or concert room. In this sense, the campaign was very timely as it was the expanding world of educational, musical, and literary activities in 1830s London that made such ‘repurposing’ of the Hall a feasible proposition. In 1834, the Society of Choral Harmonists paid £50 for the use of the hall on six evenings in April, May, and June, but negotiations to transfer the lease of the Hall to the Society fell through, possibly because of the Preservation Committee's insistence upon a commitment from the Harmonists to maintain the Hall's ‘ancient character’ and to carry on with the restoration under the guidance of an architect.Footnote 54 Another sub-committee was appointed to deal with the lord mayor, the master of the Mercers Company and members of the Gresham Committee about the possibility of relocating the Gresham lectures from the Royal Exchange to Crosby Hall.Footnote 55 Given the Hall's proximity to Gresham's own house in Bishopsgate, this was thought to be a particularly appropriate solution. It was certainly always Maria Hackett's favourite option and she wrote a number of memoranda arguing the case for the relocation;Footnote 56 however, although there was clearly some interest from the Gresham Committee, no firm commitments were ever made.

The consequence was that by 1835, the committee's funds were exhausted. The exterior of the Great Hall had been repaired, the roof reinstated, and the stonework of the oriel window had been restored but the Hall was not yet ready for occupation. Moreover, nothing had been done about the Throne Room and the Council Chamber which were still in a state of ‘hopeless dilapidation’.Footnote 57 The contracts for repairs had already amounted to £738, accounting for almost all the sum raised by the committee, and the entire remodelling and restoration was estimated to cost around £3,000. The committee, Hackett was to recollect, felt disappointed and disgusted at the apathy of their fellow citizens and no prospect of any ‘desirable appropriation’. When they discovered that their liabilities exceeded the funds at their disposal they determined upon resigning the lease – at which point Hackett offered to assume the lease herself.Footnote 58

Hackett's account of the events to the clergyman and antiquary, Thomas Hugo, emphasized that she took on the lease of the Council Chamber and Throne Room of the property as well as the Hall and their repairs were ‘my own unaided work’.Footnote 59 As a later chronicler of Crosby Hall observed, ‘she aroused the sleeping energies of some of the antiquarians of that day’.Footnote 60 Indeed, Hackett's leading role in the preservation campaign was always discreetly recognized at the time (in suitably anonymized terms) by the architects, antiquaries, and other well-wishers whom she rigorously kept up to the mark. Hackett was very much hands-on in her approach to the restoration, dealing directly with the architect Edward Lushington Blackburn (who had replaced Blore) and the builder, Mr Rudder, providing Blackburn, who was succeeded in turn by John Davies, with detailed instructions and regular requests for meetings to report on progress. As well as taking on the liabilities and costs of the original Preservation Committee, which the restoration fund had failed to cover, she invested significant sums of her own money (she later estimated nearly £3,000) into converting the Hall, and restoring and adapting the Council Chamber and Throne Room into usable premises which might then be let.Footnote 61 Although she did so in the expectation that there would be a future financial return from letting the space on a commercial basis to the Gresham Society or a similar body, it was nonetheless an extraordinary financial investment for a single and only moderately wealthy woman to make.Footnote 62 She was hampered by slow workmen and by problems in gaining possession of the premises in Bishopsgate Street which involved ‘painful altercations’ with the landlord, Williams Freeman. ‘Two or three claimants’, she complained, ‘appeared for various parts of the property at every point of the compass and were met with contradictory leases, ground plans, and awards.’ This incurred additional expenses and, more seriously, delays which led to the failure of the plan to lease the property to the Gresham Committee: when the Royal Exchange, where the lectures had been held, was burned down in 1838, Crosby Hall was still not in a fit state to host them and she lost the opportunity to arrange an immediate transfer.Footnote 63

For all her effort and commitment, Hackett encountered considerable problems and by 1842 she had been forced to sell out her interest for financial reasons, particularly given that the collapse of her pet Gresham project meant that the future use of the Hall was still uncertain. She was not receiving any rental income, despite optimistic projections, and she was also being charged for rates. Given her other philanthropic interests, the situation was not sustainable, and the lease was acquired by a committee of proprietors.Footnote 64 Although she was able to recoup some of her investment, she estimated that she had been left out of pocket by about £1,000.Footnote 65 She retained an interest in Crosby Hall for the rest of her life, however, and continued as one of the proprietors.Footnote 66 This body chiefly comprised residents of the Bishopsgate area but none of the original members of the Preservation Committee were included: that body had been a metropolitan elite of antiquaries, architects, and figures of social and political distinction and, according to Hackett's own rather tart recollection, would have nothing more to do with the Hall once the initial flurry of excitement over securing its preservation was over. But the local constituency of the proprietors listed in Hammon's pamphlet suggests the extent to which the cause of Crosby Hall had taken root amongst the neighbouring residents, who had come to appreciate its historic significance and its potential value as an amenity and as a focus for philanthropic activity.

The restoration was precisely that: the hall was ‘restored’ to what the committee of the 1840s (advised by the architect Blackburn) believed a late fifteenth-century hall would have looked like.Footnote 67 The roof of the Great Hall was one of the few elements that was original: the oriel window aside, the other windows had been reconstructed and reglazed and ornamented with the arms of subscribers and the city companies, the floor had been relaid, the walls of the Throne Room and Council Chamber had been rebuilt, and a papier maché ceiling modelled upon the original was inserted in the Council Chamber where the second oriel window had also been reconstructed.Footnote 68 A new stone facade was erected facing the church of Great St Helens and an entirely new front was built on Bishopsgate Street in the style of ‘timber houses of the period’ (see Figure 4).Footnote 69 In terms of interior furnishings, Hackett had purchased the fittings that had been used at Westminster Abbey for the coronation of Queen Victoria in 1837 at a knock down price of £10. This secured for her 20 yards of ‘Crimson Drugget with a deep yellow fringe and many yards of hemp matting’.Footnote 70 A minstrel's gallery, a raised dais, and a service screen were introduced into the Great Hall, in keeping with the accepted model of fifteenth-century halls, but with the very nineteenth-century addition of an arched recess for an organ and raised seating, installed for musical performances. The completed restoration was formally opened on 27 July 1842 by Alderman Copeland with a public dinner ‘served in the old English style’.Footnote 71

Fig. 4. The Bishopsgate Street facade, reproduced by kind permission of Historic England.

III

From the very start, Crosby Hall was presented as a building which concerned the national interest, on behalf of which it behove the public, particularly the public of London, to exert themselves, reflecting as it did on such important aspects of the city's history and the mercantile success that lay behind its current prosperity. Interest in London's past and its historical appearance was, moreover, becoming more widespread and disseminated through a range of media: historical novels, historical maps, periodical articles, topographical and antiquarian texts, panoramas, theatre and history paintings.Footnote 72 The city's rapid growth and the disappearance of so much of its earlier fabric meant that rare pre-Fire survivals, such as Crosby Hall, were the more to be appreciated, both as a visible index of the progress of modern urban society and as historical curiosities. Nonetheless, the case for preserving an ancient and decayed building, which was serving no practical function, presented considerable challenges. Unlike the campaigns to save or restore churches, where supporters could take the inherent value of the building for granted and draw upon reserves of piety and the language of the alliance of church and state in order to bolster their arguments for the preservation of the physical fabric of the church, a secular building such as Crosby Hall could claim no such special purpose and had no automatic right to consideration.Footnote 73

The significance of Crosby Hall for national history and its inherent public interest underpinned the publicity campaign that the committee launched within weeks of being first established. Its supporters identified it as yet another monument imperilled due to the absence of appropriate legislation: Alfred Kempe appealed to the generosity of the public, made necessary, he said, by the government's continued failure to contribute to the preservation of ‘public national monuments’.Footnote 74 E. J. Carlos, the most forthright critic of modern depredations on architectural antiquities of the day, wrote a series of articles for the Gentleman's Magazine which were later gathered together as a small octavo volume, with undeniably poor quality woodcuts, published by John Bowyer Nichols and sold at the relatively modest price of one shilling. Carlos described Crosby Hall as ‘A building so distinguished, though locally situated in the metropolis, belongs to the kingdom at large, and not only to the kingdom but to the world.’Footnote 75

Articles on Crosby Hall soon started to appear in the new range of cheap periodicals which were emerging in the 1830s aimed at a different more popular market, such as the Penny Magazine, Saturday Magazine, and the Mirror of Literature, Amusement and Instruction, whose weekly numbers sold for 2d.Footnote 76 The rhetoric of national importance and the Hall's role in England's history was repeated, but with a different nuance that endowed it with relevance to the wider community of Londoners: thus, the Penny Magazine represented it not as the private property of single wealthy landowner, but as part of the ‘public inheritance’ of the population at large, as tangible evidence of the diversified wealth generated by the labours of successive generations.Footnote 77

Further histories and architectural studies followed in the 1830s and 1840s and the Preservation Committee itself published regular summaries of the history of the building and its significance in its appeals for further subscriptions. In 1836, Maria Hackett launched a competition for the best historical and graphic illustrations of the Priory Church of St Helen, Gresham College, and Crosby Hall for which praemia to the value of 100 guineas were to be awarded. This competition was not so much an exercise in raising funds as raising the profile of the building and demonstrating its historical importance.Footnote 78 Committee members such as the antiquary John Britton, the writer Charles Crowden Clarke, and the musician Vincent Novello were pressed by Maria Hackett into giving public lectures at the Hall.Footnote 79 Whilst the intended audience and readership varied, these ventures all insisted on the national importance of Crosby Hall and the inherent interest of its historical associations: these may be summarized as the Hall as an example of medieval domestic architecture, illustrative of ‘olden time’; the Hall's associations with historical characters, particularly Richard III and Shakespeare; and the Hall's significance as a symbol London's commercial history and the success of its mercantile class.

The descriptions of Crosby Hall did not simply identify it as a specimen of gothic architecture: as John Britton noted in Architectural antiquities, buildings like Crosby Hall were generally inferior to cathedrals in terms of the quality of the gothic architecture that they displayed, but they were of rather more interest in terms of their historical associations and as being illustrative of the domestic economy and the manners and customs of earlier periods.Footnote 80 The telling point is that Crosby Hall was being applauded as a specimen of domestic architecture, a category that only began to be conceptualized from a historical perspective in the early nineteenth century. Indeed, ‘domestic architecture’ was not a term that was used by eighteenth-century antiquaries: their focus was rather upon ecclesiastical and military structures and little, if any, attention was devoted to traditions of vernacular architecture.Footnote 81 By 1804, however, Storer and Grieg had identified Crosby Hall as one of London's ‘most elegant specimens of ancient domestic architecture’ and J. P. Malcolm discussed it in his historical sketch of ‘domestic architecture’ in the second edition of Anecdotes of London of 1810.Footnote 82

Smith, Storer, and Malcolm and their peers had identified a type of architecture which was otherwise almost entirely disregarded, chiefly as a result of their interest as antiquarian draughtsmen in the picturesque qualities of half-timbered buildings. Antiquaries and architects followed their lead some twenty years later: more widespread appreciation of domestic antiquities and domestic architecture became evident from the late 1820s and 1830s, with greater attention being given to the social, economic, and political contexts in which these buildings were erected. This development coincided with and contributed to the Victorian celebration of ‘olden time’ and of domesticity in general. The term ‘domestic’ became ubiquitous in antiquarian publications: histories of domesticity and domestic life appeared alongside studies of domestic architecture, which was valued precisely because it was illustrative of domestic manners and customs, or the ‘domestic economy’ of olden times.Footnote 83 The term ‘olden times’ was protean and non-specific and could be deployed with reference to any period from Roman Britain to the early eighteenth century: in the context of towns, it was generally associated with the late fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries, given that few buildings survived from earlier periods. Its architectural style was assumed to be gothic, but could encompass the Italianate influences of the later sixteenth and seventeenth centuries too. More generally, its usage carried connotations of nostalgia for a simpler era, in which there was greater social harmony: hence the constant association of olden time with communal activities engendering social harmony such as pageantry and feasting.Footnote 84

Amongst modern architectural historians, the Victorians’ interest in domestic architecture has generally been associated with a rediscovery of Elizabethan style and its deployment in country house architecture by such doyennes of the tudorbethan (or jacobethan) style as Edward Blore, William Burn, or Anthony Salvin.Footnote 85 This is not without reason, both in terms of the designs that were executed and the original buildings that the architects studied and sought to emulate. Publications such as Nash's Mansions of England in the olden time (1839) or Clarke's The domestic architecture of the reigns of Queen Elizabeth and James the First (1833) focused on gentry seats and houses of the nobility, chiefly from the late fifteenth, sixteenth, and early seventeenth centuries. However, it is important to remember that these architects also drew on urban examples for their designs and, just as there was an emerging canon of Elizabethan gentry houses featuring in antiquarian studies and architectural designs, there was equally a list of urban structures, such as Crosby Hall, the New Inn at Gloucester, or St Mary's Guildhall Coventry, which were regularly cited in discussions of domestic architecture of the late medieval and sixteenth-century style.Footnote 86 Antiquaries with an interest in urban history attached particular importance to these buildings, not only because they were illustrative of the manners and customs of past ages in their respective towns, but more specifically because the self-evident wealth and magnificence which they embodied were a testimony to the power, prosperity, and influence of towns and the mercantile elites of the past. According to the dominant whiggish narratives of the day, the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries saw the dissolution of the power of the feudal nobility, the establishment of domestic peace and stability, and the growth of commerce and manufactures: happy developments of which the domestic and civic architecture of the nation's historic towns was the visible evidence. Sir John Crosby's success as a wool merchant was a harbinger of London's nineteenth-century commercial prosperity and Crosby Hall, therefore, exemplified not only his personal riches, but also the increasing wealth and prosperity of London that derived from expanding trade and greater domestic stability. ‘Surely’, wrote the anonymous author writing on behalf of the Preservation Committee in 1832, ‘the affluent and high-minded citizens of the metropolis of the British empire, will not permit so proud a monument of civic splendour to fall to decay.’Footnote 87

As a rare exemplar of urban domestic architecture in London preceding the fire, Crosby Hall also offered an indication of what other palaces of the nobility and wealthy gentry might have looked like. The survival of the vaults allowed architectural antiquaries to reconstruct the original plan of the building. The architect Edward Blackburn suggested that it had originally been built as a double courted mansion, a style which was typical of the transition from houses built for defensive purposes to houses built for domestic comfort and display of wealth and status and which was characteristic of the later fifteenth century.Footnote 88 Crosby Hall was placed in a typology of halls or noble residences such as Penshurst, Eltham, and Haddon Hall, all of which conformed to a basic type of house built around a great hall, with a service passage covered by a minstrel's gallery and domestic offices at one end and private chambers at the other. Beyond this, Crosby's principal architectural attractions were the oriel window and the richly carved roof which had survived more or less intact. Architectural antiquaries were also fascinated by the fact that the Great Hall boasted both a louvre in the roof and an elaborate fireplace: it had been originally assumed that the introduction of the technology of chimneys and mural fireplaces obviated the need for the central fireplace and louvre of early great halls. The evidence of Crosby Hall indicated that both mural and central fireplaces existed simultaneously and was therefore of considerable interest for historians of domestic architecture.Footnote 89

Thus, Crosby Hall was promoted as an exemplar of domestic architecture, of ‘scientific’ value for the modern architect and a specimen of the ‘pure and refined’ taste of earlier times from which the public at large could benefit.Footnote 90 It was for this reason that architects such as Blore, Salvin, Blackburn, and Davies were willing to be involved in its restoration and why the recently established Royal Institute of British Architects offered the Soane medallion for an essay on the reconstruction of Crosby Place in 1841: a competition that was won by John Woody Papworth's ‘Memoir of Crosby Place’.Footnote 91

But it was also rich in other historical associations, and particularly in connection with Shakespeare and Richard III. Following Crosby's death in 1475, his widow had sold the leasehold of the property to Richard duke of Gloucester, and, according to Shakespeare, it was at Crosby Hall that as Richard III he had conspired to murder the princes in the Tower. In 1790, Thomas Pennant had been reticent on the subject, simply noting that Richard III had lodged at Crosby Hall, as Stow had also noted in the Survey of London: at this point, momentum had yet to build up behind the celebration of its Shakespearean connections. In the nineteenth century, it became an increasingly important aspect of the narrative that was being constructed around the Hall, overshadowing its origins as a merchant residence. By 1829, even before the Preservation Committee had begun its campaign, the Hall featured in the Mirror as number 11 in the series ‘Illustrations of Shakespeare’, accompanied by a small and rather crude woodcut (see Figure 5).Footnote 92 One of the early promotional pamphlets suggested that the Hall had even been the location for some of the earliest performances of Shakespeare's plays.Footnote 93 As a later writer on Crosby Hall explained, its ‘special attraction’ derived not simply from the fact that it had been a royal residence, but, ‘from the notice which it has on this account received from one, who has only to make a place the scene of his matchless impersonations in order to confer on it an immortality of interest’.Footnote 94 Carlos, writing in 1832, was sceptical about how much could really be known about Richard III's residence at Crosby Hall or of the Hall's role as a backdrop to the violent events of his reign,Footnote 95 but he was taken to task by the Penny Magazine for such pedantry, the latter citing the supposedly unequivocal authority of Thomas More that Richard really did plot the murderous deed in the Council Chamber.Footnote 96 For the Victorians, Crosby Hall seemed to offer a tangible point of contact with Shakespeare, which was all the more valuable as only sketchy details otherwise survived of his time in London. As John Wykeham Archer lamented in Vestiges of old London, ‘we have not a vestige whereby to distinguish the locality which produced the wondrous creations of Hamlet, Macbeth, Lear’.Footnote 97 Great, then, was the satisfaction when the antiquary Joseph Hunter finally established that Shakespeare had indeed lived in the parish, having identified his name in a 1598 subsidy roll, where Shakespeare paid a levy that was indicative of a substantial property.Footnote 98 Could he even have lived next door to Crosby Hall?

Fig. 5. Crosby Hall from Mirror of Literature Amusement and Instruction, 19 May 1829, p. 234, reproduced by kind permission of Special Collections, University of Leicester.

Richard III was far from being the only illustrious occupant of the Hall, however, and as the nineteenth century progressed, the property history of the Hall was gradually filled in and the roll call of distinguished personages associated with Crosby Hall expanded to include a number of other characters regarded by the Victorians as distinguished in the annals of history. In a splendid piece of historical irony, Thomas More, arch calumniator of Richard's posthumous reputation, was also associated with Crosby Hall. In the nineteenth century, it was believed that More might have acquired the lease as early as 1509 and held it until 1523 when he leased it in turn to his friend, the merchant Antonio Bonvisi.Footnote 99 More, it was assumed, retreated to Crosby Hall for leisure and study, entertaining Erasmus and other humanists – even the king – and he featured ever more prominently in historical notices.Footnote 100 At the ceremony to celebrate the laying of the foundation stone of the Council Chamber in 1836, the Hall was decorated with a picture depicting the interior in 1520 ‘when inhabited by Thomas More’, with More introducing Holbein to Henry VIII,Footnote 101 while the Council Chamber was hung with painted ‘tapestries’ depicting historical scenes, including More at work on the manuscript of Utopia.Footnote 102 It is questionable, however, whether More ever actually occupied the building himself: he never purchased the lease until 1523 from John Rest, who had in turned purchased it from Sir Bartholomew Reed (both of whom were prominent merchants and city men serving as mayor in 1523 and 1502–3 respectively). Six months later the lease had passed to Bonvisi.

Subsequent occupants included the merchants Germayne Cioll and George Bond, while Sir Thomas Gresham, who enjoyed a far higher reputation as merchant, a patron of the arts and sciences, and founder of the Royal Exchange, had lived in the same ward of Bishopsgate and was buried, like Sir John Crosby, in St Helen's Church which neighboured Crosby Hall. Gresham, suggested Charles Mackenzie, must have discussed his original idea for an Exchange (the source of so much of London's commercial wealth) based on the Amsterdam Bourse with Bonvisi, Cioll, and Bond at Crosby Hall.Footnote 103 A personal link with Crosby Hall was even established when it was realized that Gresham's niece had married Cioll later in the sixteenth century.Footnote 104 The Hall was being ever more closely entwined with the mercantile success of early modern London. In the early seventeenth century, Crosby Place (as it was then known) was the residence of foreign ambassadors, including the duc de Sully, which allowed its historians to claim for it a role as the backdrop to scenes of international diplomacy. Ownership of the lease had by this time passed to Sir John Spencer in 1594 who used Crosby Place as his mansion house during his mayoralty; from Spencer it descended to the Compton family and thence to the earls of Northampton. Whilst owned by the Spencer Comptons, it was the residence for a short period of time of the dowager countess of Pembroke, Mary Sidney, sister of Sir Philip Sidney, who was, as Thomas Hugo put it, ‘immortalised by Ben Jonson’. A tenuous link was thereby engineered not only with Mary Sidney herself, but also with her brother, renowned as the flower of English chivalry, and the Jacobean dramatist, whose reputation was also rising.Footnote 105 The Spencer Compton connection proved fruitful in another dimension too, as the Preservation Committee had secured the agreement of the marquess of Northampton, the descendant of the original Sir John, to join the Preservation Committee. Mackenzie, in his lecture given at the celebrations in 1836, was able to pay graceful tribute to the hospitality of Sir John Spencer as well as Sir John Crosby.Footnote 106

In addition to exploiting Crosby Hall's connections with familiar characters of English history, the supporters of Crosby Hall were also able to assimilate it into the narratives of merrie England and olden time as a scene of civic pageantry, mercantile hospitality, and good cheer. At a time of considerable debate over political reform and the social and political contribution of the middle classes, the narrative around Crosby Hall offered a riposte to those who, like Pugin or Disraeli, associated such charity and benevolent social relations with a rural, landowning class and with the traditions of the Roman Catholic church. It was of a piece with the liberal, whiggish historiography of the day that emphasized the specifically urban origins of modern Britain.Footnote 107 The very scale on which the house was built, argued Charles Mackenzie, afforded sufficient evidence that it had been designed for hospitality and that ‘[Crosby] possessed the spirit which in every age has actuated the merchant princes of this land’, that is the provision of hospitality and charity. The dimensions of the Great Hall bespoke ‘wealth, liberality, a frank spirit and a joyous heart’.Footnote 108 Similarly, Papworth described it as a monument of the ‘affluence and easy hospitality of the English merchant’,Footnote 109 while the Penny Magazine, with its distinctly middling readership, referred to the Great Hall as the ‘banqueting hall’, emphasizing its function as the site of communal feasting.Footnote 110

IV

Despite the widespread acknowledgement of Crosby Hall's significance as the most important specimen of domestic architecture in the metropolis, its continued existence could not be taken for granted and there were no legal measures in place to ensure its preservation. The Crosby Hall Literary and Scientific Institution gave way to the Metropolitan Evening Classes in 1848. In 1857, there were rumours again that the proprietors intended to raze the property and redevelop the site into offices (it was at this point that Hackett corresponded with Thomas Hugo, the principal of the Metropolitan Evening Classes, to fill him in on the background history of Crosby Hall). While this threat never materialized, the lease was sold shortly afterwards and the Hall was converted, first into a wine merchant's warehouse, and later into a restaurant in 1868. As the promotional literature was at pains to point out, the banqueting hall had at last been restored to its ‘original purpose’.Footnote 111 The Freeman family sold the freehold of the Hall in 1871, having disposed of the rest of the Bishopsgate property by auction, to Messrs Gordon and Co., who continued to operate it as a restaurant. In 1907, it faced destruction once more as the property was sold to the Bank of India for demolition: the redevelopment of the area around Liverpool Street Station into a business district of offices and commercial premises could not accommodate such historical curiosities any longer. But the building's historical significance had by now been firmly established and its demolition could not go unchallenged. There were vociferous protests against the proposal from architects, antiquaries, and members of the civic elite. Even the king made it known that he hoped that the building could be saved.Footnote 112 In the end, it was dismantled and moved to its current location on Cheyne Walk where it was to become a hall of residence in Patrick Geddes's scheme for a revival of learning based around Thomas More's Chelsea residence.Footnote 113 With a 1920s Arts and Crafts addition, Crosby Hall enjoyed a new phase of its existence as part of the University of London, until it was purchased by its current owner, Christopher Moran, from the freeholder, Greater London Council, in 1988.Footnote 114 Moran has transformed it into a composite Tudor building, borrowing from favourite examples of sixteenth-century architecture such as Kirby Hall Northamptonshire, while the 1920s extension has been given a Jacobean makeover.

V

Crosby Hall exemplifies the qualities needed for a building to acquire sufficient value for it to be preserved in the face of urban improvement: aesthetic and age value were important, but the decay into which it had fallen by the turn of the century, and which first attracted antiquarian attention, was not essential for its continued appreciation as a picturesque structure. Rather, the crucial factors were the historical associations it provoked and the potential it offered to forge connections with the famous characters and events of national history. A comparison with another building in Bishopsgate, Sir Paul Pindar's house, sets Crosby Hall's unique combination of aesthetic and historic value into relief. Having largely escaped the fire, there were a number of other structures in the vicinity still surviving of a comparable age to Crosby Hall, of which Sir Paul Pindar's house came closest in terms of architectural merit.Footnote 115 Like Crosby Hall, it could also claim connection with a prominent merchant: Pindar had been successful in the Italian trade and in the eastern Mediterranean, serving as James I's ambassador to Constantinople.Footnote 116 J. T. Smith illustrated the house as an example of domestic architecture in the Antient topography of London (1815); Archer depicted it in a series of plates in Vestiges of old London and Thomas Hugo featured it in the first of his ‘Walks in the City’ for the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society.Footnote 117 However, despite Pindar's mercantile wealth and political importance, it was impossible to construct a narrative comparable to Crosby Hall's story: it lacked the density of associations with the monarchy and the civic elite of London and with famous historical figures with whom the nation as a whole could identify. As the Mirror noted, ‘Unlike the shattered bulwarks of an ancient fortress or the crumbling walls of some olden convent, this relic is interesting from its antiquity only; it has no striking events connected with its history to awaken any stronger feeling.’Footnote 118 It steadily deteriorated in condition and was demolished in 1890.

More broadly, the Crosby Hall campaign seems to have served as an inspiration for other ventures to save historic buildings: the publicity for the campaign to save St John's Gate, Clerkenwell, in 1845 (badly dilapidated and threatened by the Metropolitan Building Act) suggested that once restored it too might be used as a literary and scientific institution for the benefit of the inhabitants of Clerkenwell.Footnote 119 Around the same time, there was also a suggestion that members of the British Archaeological Association (BAA) should club together to buy Burgh Castle in Norfolk according to a model reminiscent of the committee of proprietors at Crosby Hall.Footnote 120 The antiquary and founder member of the BAA, Thomas Wright, seems to have been similarly inspired by the example of Crosby Hall as he drew attention to the ‘few interesting specimens of the ancient architecture of ancient London’ still in existence, but in danger of disappearance ‘unless rescued from the hands of the destroyer for some public object. Might they not’, he suggested, ‘be bought by the government, or by the city authorities, for museums, or for the meetings of learned societies?’Footnote 121

Overall, it could be argued that Crosby Hall survived only because of the determination of a single woman, Maria Hackett, who intervened once the enthusiasm of less committed architects and antiquaries had dissipated after the first flush of publicity and interest. This in itself constitutes a remarkable story of female endeavour in a domain that is generally depicted as an overwhelmingly masculine one in this period. But although Hackett and the other supporters of Crosby Hall were disappointed by their failure to win financial support and recognition from London's mercantile elite, through their constant efforts to celebrate and illustrate the history and importance of Crosby Hall they were successful in inscribing it in the wider perception of the metropolis’ and the nation's past.Footnote 122 This was essential for its long-term survival. Crosby Hall was saved because it was possible to elevate it above the local and particular so that it became the embodiment of a national narrative that combined the history of the monarchy and the capital's rise to commercial dominance with a celebration of the nation's literary heritage represented by Shakespeare and Jonson, and the traditions of Christian humanism represented by Thomas More.

Crucially, the history of Hackett and the Crosby Hall campaign itself became a part of that heritage. The fact that the lease had initially been taken by a committee and was reliant on the generosity of the public for the furtherance of its aims, rather than being dependent upon an individual benefactor or the obligations enjoined by religious faith, meant that by necessity a more inclusive language of public interest was adopted to promote its aims, and that the future use to which it would be put had to be justified in terms of wider social benefits as well as economic realities. The role played by Miss Hackett, who had ‘aroused the citizens’ to the enormity of the sacrilege, offered the additional attraction of a very particular brand of female heroism.Footnote 123 The protests of 1907/8 against the proposed demolition of the Hall emphasized the fact that it had originally been saved through public subscription and that there was therefore now an obligation to the public to ensure its future.Footnote 124 By this point, the memory of the recent campaign of the 1830s and 1840s meant that the same arguments that had been successfully rehearsed then could be prevailed upon again, but with added cogency, given that the Hall now also embodied the civic feeling and public spirit of that earlier generation. In terms of the longer history of the heritage movement, this successful harnessing of the philanthropic potential of civil society on behalf of architectural preservation is a noteworthy development as is the recognition of the building's increased public significance as a consequence of such communal engagement. These additional layers of meaning and value were, in 1908, critical factors in ensuring the building's (partial) physical survival in its new location in Chelsea.