Introduction

A well-performing health workforce – one that is available, competent, responsive and productive – is essential for health systems to serve population needs effectively and improve health worldwide [World Health Organization (WHO), 2007a]. However, in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) health improvements are being hindered by provider shortages, skill mix imbalances, inequitable distribution, suboptimal work environments and a weak knowledge base to improve the situation (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Evans, Anand, Boufford, Brown, Chowdhury, Cueto, Dare, Dussault and Elzinga2004). Improving performance of the health workforce has been identified as a key strategy to accelerate progress on many Sustainable Development Goals (WHO, 2017a).

One strategy that has been devised to address this problem is the design of contracts with performance-based incentives (PBIs), defined as the transfer of money or other material rewards conditional on taking a measurable action or achieving a predetermined performance target (Eichler and Levine, Reference Eichler and Levine2009). Over the past two decades, PBIs have been an increasingly popular management tool used by health sector managers to improve health services delivery in LMICs (Meessen et al., Reference Meessen, Soucat and Sekabaraga2011), where salary levels are often inadequate to attract, retain and motivate the health workforce (Henderson and Tulloch, Reference Henderson and Tulloch2008; Willis-Shattuck et al., Reference Willis-Shattuck, Bidwell, Thomas, Wyness, Blaauw and Ditlopo2008). As incentive payments are directly linked to measured performance, supply side PBIs can be used by managers – in addition to other performance management tools such as training and guidelines – to try and influence specific actions of health care providers (Eichler and Levine, Reference Eichler and Levine2009). Notably, since 2008, the Health Results Innovation Trust Fund has invested US$ 420 million to PBI projects globally, while the International Development Association added another US$ 2.4 billion to these funds (World Bank, 2014). As a result of these large investments, supply-side PBIs have been implemented and scaled up in many countries, especially in Africa (Fritsche et al., Reference Fritsche, Soeters and Meessen2014).

Several studies and evaluations have been conducted to assess these interventions, providing evidence that PBIs have had positive effects (Kandpal, Reference Kandpal2017) – for example, increased rates of institutional deliveries and provision of neonatal services were reported in Rwanda (Basinga et al., Reference Basinga, Gertler, Binagwaho, Soucat, Sturdy and Vermeersch2010). However, a recent study in the same country found that PBIs improved efficiency but not equitable access to health services (Lannes et al., Reference Lannes, Meessen, Soucat and Basinga2016), while unintended negative consequences were documented in another study, including the manipulation of reports to maximise results and neglect of important activities not incentivised (Kalk et al., Reference Kalk, Paul and Grabosch2010). Evidence from other countries in Africa suggests that poorly designed PBI schemes may have additional negative implications for the health system (Paul et al., Reference Paul, Albert, Bisala, Bodson, Bonnet, Bossyns, Colombo, De Brouwere, Dumont, Eclou, Gyselinck, Hane, Marchal, Meloni, Noirhomme, Noterman, Ooms, Samb, Ssengooba, Touré, Turcotte-Tremblay, Van Belle, Vinard and Ridde2018); for example, a study in Tanzania found that perceptions about unfairness in the distribution of financial bonuses reversed the motivational effect of PBI schemes (Chimhutu et al., Reference Chimhutu, Songstad, Tjomsland, Mrisho and Moland2016). Where PBIs have been successful, the role of health managers as well as community leadership was found to be central to improving performance (Mabuchi et al., Reference Mabuchi, Sesan and Bennett2018).

Despite these insights, knowledge gaps remain in our understanding of factors that may promote or hinder successful PBI scheme implementation. It is well recognised that a careful consideration of context is crucial to the success of PBI schemes, as in any other health intervention (Ssengooba et al., Reference Ssengooba, McPake and Palmer2012; Olafsdottir et al., Reference Olafsdottir, Mayumana, Mashasi, Njau, Mamdani, Patouillard, Binyaruka, Abdulla and Borghi2014). However, a recent systematic review found that only few evaluations explored in-depth the influence of contextual variables (Renmans et al., Reference Renmans, Holvoet, Orach and Criel2016a). The same review also found that the majority of PBI studies were conducted in African countries, with little attention to other contexts of implementation. Lastly, most reviewed studies focussed on health care workers, but views and experiences of local managers have rarely been incorporated. In particular, we noted a dearth of evidence from Asian countries and regions such as China, India, Pakistan and the Greater Mekong Subregion – whose large and growing populations are in urgent need of more well-trained and motivated health care professionals. We propose that important insights about the appropriateness and design of performance management tools – including PBI schemes – could be gained from managers based in Asian countries, owing to the unique socio-cultural factors and health systems constrains in several Asian LMICs (Dieleman et al., Reference Dieleman, Cuong, Anh and Martineau2003; Henderson and Tulloch, Reference Henderson and Tulloch2008; Grundy et al., Reference Grundy, Khut, Oum, Annear and Ky2009; Connell, Reference Connell2010; Hafeez et al., Reference Hafeez, Mohamud, Shiekh, Shah and Jooma2011; Tao et al., Reference Tao, Zhao, Jiang, Ma, Wan, Ma and Xu2013; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Duke, Wuliji, Smith, Phuong and San2016; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Liu, Sun, Yip, Wagstaff and Meng2016).

Against this background, this paper reports findings from a study which aimed to investigate – from the perspective of senior health sector managers – prospects for the introduction of PBIs in their settings. Qualitative research for this project was conducted in Cambodia, China and Pakistan to complement the existing stock of knowledge, mainly based on experiences in Africa, with perspectives from three Asian countries characterised by different health systems, administrations and cultural backgrounds.

Conceptual framework

A meaningful examination of the suitability of PBIs requires engagement with the theoretical assumptions underpinning this type of intervention. As Renmans et al. (Reference Renmans, Paul and Dujardin2016b) pointed out, PBIs can be understood through the lens of the principal – agent relation, a classic problem in economics which focuses on issues resulting from the delegation of authority and responsibility (Stiglitz, Reference Stiglitz1989). In the health sector, this problem can be seen as one involving the manager of a health programme (who acts as a ‘principal’ and sets forth goals and performance targets) and health providers (who act as ‘agents’ of the principal and are responsible for meeting the targets). The principal relies on the actions of the agent to achieve a desired outcome, but the agent may have differing needs and wishes (or ‘utility functions’) to the principal. As a result of this tension, the agent cannot be relied upon to act entirely in the way desired by the principal. Providers often benefit from greater knowledge about the local context and activities, resulting in information asymmetry that allows the agent to evade supervision and execute a personal agenda. To address this problem, the principal can design a compensation system (a contract) with financial or other material rewards, which motivates agents to behave in the principal’s interest, even when they cannot fully monitor what an agent is doing.

Yet, evidence from the social sciences has questioned the assumption that financial gains alone are a strong motivation to produce more and better outcomes, demonstrating the multi-faceted nature of reward systems. For example, distinctions have been made between intrinsic and extrinsic sources of motivation (Ryan and Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2000; Gagné and Deci, Reference Gagné and Deci2005; Paul and Renmans, Reference Paul and Renmans2018); in the context of frontline health care providers, the latter would stem from rewards or sanctions coming from an external source and the former would be driven, in part, by the satisfaction derived from providing care to patients. The literature has also highlighted the importance of other non-material rewards (Paul and Robinson, Reference Paul and Robinson2007), which may include social motivation (peer-pressure and recognition from the community or co-workers) and internal motivation (including moral and intrinsic). Thus, both principals and agents, in reality, do not always function as actors motivated only by self-interest and material rewards (Cuevas-Rodriguez et al., Reference Cuevas-Rodríguez, Gomez-Mejia and Wiseman2012), as the paradigm of the ‘homo economicus’ would imply.

Furthermore, meaningful implementation of schemes based on financial incentives requires a local system of institutions, organisational structures and capacities which can enable both principals and agents to act in accordance with the stipulated performance contract. In practice, however, the ideal set of conditions for optimal programme implementation is difficult to achieve, especially in LMICs. For example, the presence of multiple principals – who may have conflicting goals, needs and demands – is likely to dilute the impact of incentives compared to situations in which there is a single principal (Shapiro, Reference Shapiro2005; Renmans et al., Reference Renmans, Paul and Dujardin2016b); in LMICs, where providers often work on multiple programmes funded by different donors, this is a common situation. Other contextual factors – such as weak local accountability mechanisms, limited bureaucratic capacities, gaps in information systems and wider issues of organisational culture – have also been shown to affect the implementation of PBIs (Paul et al., Reference Paul, Albert, Bisala, Bodson, Bonnet, Bossyns, Colombo, De Brouwere, Dumont, Eclou, Gyselinck, Hane, Marchal, Meloni, Noirhomme, Noterman, Ooms, Samb, Ssengooba, Touré, Turcotte-Tremblay, Van Belle, Vinard and Ridde2018).

In consideration of these points, we designed a conceptual framework integrating two analytical domains (Figure 1). First, we aimed to explore in practice the fundamental assumptions of PBIs, with particular attention to the value of monetary vs non-monetary incentives and other sources of health worker motivation. Second, we examined practical challenges related to the design or implementation of PBIs, including the extent to which local institutions have systems in place to monitor performance and provide fair distribution of incentives. Based on insights from previous studies (Paul et al., Reference Paul, Albert, Bisala, Bodson, Bonnet, Bossyns, Colombo, De Brouwere, Dumont, Eclou, Gyselinck, Hane, Marchal, Meloni, Noirhomme, Noterman, Ooms, Samb, Ssengooba, Touré, Turcotte-Tremblay, Van Belle, Vinard and Ridde2018), we summarised and grouped the variety of design and implementation challenges into four inter-linked categories, as illustrated in the rectangular boxes in Figure 1: (1) the availability of sufficient resources to deliver relevant health services by agents (and thus meet the performance targets); (2) a well-functioning monitoring systems to link performance with rewards; (3) organisational and cultural norms that support merit and fair performance management; and (4) sufficient authority of principals to dispense rewards based on performance information.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework summarising the theoretical basis of performance-based incentives and elements that are critical for appropriate design and implementation.

Details of our methodology and our criteria for country and interviewee selection are provided in the next sections.

Methods

Study setting

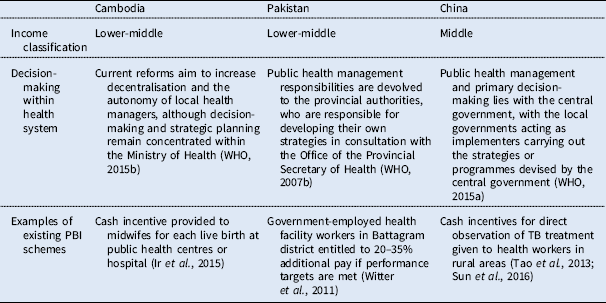

Three Asian LMICs were purposively selected from among those where the research team had strong relationships from ongoing work, to act as case studies representing diversity in terms of GNI per capita (US$ 1140 in Cambodia, US$ 8260 in China and US$ 1510 in Pakistan) (The World Bank, 2016), the availability of human resources for health (as indicated by nursing and midwifery personnel: 1/1000 in Cambodia, 1.7/1000 in China and 0.6/1000 in Pakistan) (WHO, 2017b), as well as different administrative systems. A summary of each country’s income-level and extent of health system decentralisation, along with examples of PBI schemes implemented is provided in Table 1. In Pakistan, health services strategic planning and delivery are devolved to the provinces, whereas in Cambodia there is an ongoing move towards decentralisation and in China there is a greater degree of centralisation of decision-making (WHO, 2007b, 2015a). In all three study countries, different types of PBI schemes have been implemented, scaled-up and are likely to be expanded in the near future (see e.g. Witter et al., Reference Witter, Zulfiqur, Javeed, Khan and Bari2011; Tao et al., Reference Tao, Zhao, Jiang, Ma, Wan, Ma and Xu2013; Matsuoka et al., Reference Matsuoka, Obara, Nagai, Murakami and Chan Lon2014; Ir et al., Reference Ir, Korachais, Chheng, Horemans, Van Damme and Meessen2015; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Liu, Sun, Yip, Wagstaff and Meng2016).

Table 1. Overview of country characteristics

Note: PBI=performance-based incentive.

Data collection

Data collection for this study involved semi-structured qualitative interviews with senior managers (principals) responsible for resource allocation and performance management in publicly and privately funded health programmes, implemented in numerous primary health facilities or in charge of large tertiary health facilities. We decided to focus on this group because perspectives of managers can be very important for success and ownership of PBI schemes, but are rarely studied in LMICs (Olafsdottir et al., Reference Olafsdottir, Mayumana, Mashasi, Njau, Mamdani, Patouillard, Binyaruka, Abdulla and Borghi2014; Paul et al., Reference Paul, Sossouhounto and Eclou2014; Paul et al., Reference Paul, Albert, Bisala, Bodson, Bonnet, Bossyns, Colombo, De Brouwere, Dumont, Eclou, Gyselinck, Hane, Marchal, Meloni, Noirhomme, Noterman, Ooms, Samb, Ssengooba, Touré, Turcotte-Tremblay, Van Belle, Vinard and Ridde2018). Given the prospective nature of this research project and our primary focus on pre-implementation issues, we only include participants who had not yet been involved directly in PBI schemes and thus could provide more neutral, unbiased views on the questions under investigation.

In each country, three to five health sector managers working in vertical programmes, such as HIV and tuberculosis, as well as hospitals and primary health care were purposively selected as the ‘seed’ group for initial interviews. Following interviews with the first group, snowball sampling was used to identify additional interviewees with the aim of achieving saturation in the analysis of the research domains in the conceptual framework. Interviews were conducted both in the capital cities and at least one provincial city in each country. Overall, 13, 10 and nine interviews were conducted in Pakistan, China and Cambodia, respectively (Table 2). The 32 health sector managers interviewed consisted of 14 government health department officials, two technical advisors to high level government policymakers on performance management, eight tertiary government hospital managers and eight non-profit health service delivery organisation representatives.

Table 2. Summary of interviews conducted

Following informed consent, semi-structured interviews lasting between 30 and 90 minutes were conducted face-to-face in English or the local language according to the interviewee’s preference. Interviews were conducted by researchers (M.S.K., M.L. and S.W.) with expertise in qualitative methods, all of whom had worked in the countries and were familiar with the local context. Based on the set of concepts discussed above, a semi-structured interview guide was used to explore managers’ perceptions about the suitability of PBIs in the country or the organisational context where the interviewee worked in. Interview schedules were tailored to the specific expertise each participant could bring. Interviewees were given space to express their own opinions and ideas, and in many cases, their responses shaped the flow of the interviews. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim, with the exception of four instances when the participants preferred extensive handwritten notes.

Analysis

We used a combination of deductive and inductive thematic analysis, based on an interpretive approach (Rice and Ezzy, Reference Rice and Ezzy1999). In order to organise the data and identify salient themes, we coded each anonymised transcript line by line. A preliminary coding frame was devised by I.R. comprising the broad themes described in the conceptual framework and additional sub-themes emerging from the data. The themes were independently reviewed by M.S.K. to ensure agreement on the coding frame. M.S.K. and I.R. compared initial categories with subsequent codes to refine the analytical framework, until all the data were sorted in line with the constant comparison technique (Glaser and Strauss, Reference Glaser and Strauss1967). In the presentation of results, themes and sub-themes are illustrated with excerpts from the interviews.

Ethical approval was granted by the National University of Singapore research ethics committee and written informed consent was provided by each interviewee.

Results

Taken together, our results illustrate many potential limitations in the applicability of PBIs within the institutions and cultural contexts they worked in. Many health sector managers (principals) believed that health care providers are not always primarily driven by monetary rewards and that non-monetary rewards – such as recognition from direct supervisors, career development and greater involvement in decisionmaking – could have a greater influence on performance. They also highlighted several factors related to the design and implementation of PBIs that they felt would influence the impact of PBIs on provider performance, as we will detail in the sections below. Following the structure of our conceptual framework, we first present interviewees’ perspectives about issues related to the theoretical foundations of PBIs as a means to improve performance and then we present findings related to the design or implementation of PBIs. Our key findings in relation to the conceptual framework presented in Figure 1 are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3. Summary of assumptions and contextual requirements underlying use of performance-based incentives (PBIs) and examples of how these were not fully met in our study settings

Issues raised with respect to the theoretical basis of PBIs (agents are primarily motivated by financial rewards)

Incentives that serve other interests, including gains in social status and professional development, may matter to providers more than monetary rewards

Diverse respondents – including private sector primary health services managers in Pakistan, private hospital managers and government public health officials in China and an international non-governmental organisation manager in Cambodia – explained that an incentive system based solely on monetary gains would be ineffective in their context as providers have additional concerns and expectations. Particularly in Cambodia and Pakistan, actions that could strengthen or weaken the reputation of agents within their community – such as feedback of patients on social media outlets – were seen as more important than incentive payments (Cambodia – 1, 3, 4 and Pakistan – 2, 8, 11). Other respondents believed that non-monetary rewards that contribute to professional development or improve work experience – including career advancement through promotion, training opportunities and access to safer work environments – may be more effective motivators than small financial incentives. For example, one manager in China explained:

‘At the end of June, we will have an annual conference in Nanchang, about 1700 doctors will participate in the conference. For the best ones, we will cover their fees for participating in the conference, including transportation, registration, and accommodation (…) Additionally, we will select the best research papers. We will reward them with a certificate of best paper. Sometimes we will give them a monetary prize, but it is very rare. Usually we will just give them recognition and moral encouragement’ (China – 1).

Similarly, one informant in Pakistan was in favour of social recognition and ‘film award’ style ceremonies (Pakistan – 7), adding that failure of managers to publicly acknowledge deserving providers can lead to demotivation. Our results also indicated that non-monetary rewards were perceived by some decision-makers in Pakistan and Cambodia as being more sustainable than PBIs, with PBIs associated with short term gains that are truncated when the financial incentive funding source dries up.

Effective management of human resources and alignment of values between supervisors and employees can be more important than financial incentives

Participants in each country (Pakistan – 1, 6, 8; Cambodia – 3, 4, 5; China – 7) felt strongly that performance could be improved without monetary incentives owing to sound management and supervision of human resources. Some respondents stressed that a good manager should be supportive, understand providers’ needs, and establish a constructive dialogue with them to agree on targets and approaches (Cambodia – 9, Pakistan – 2, 3). For example, a public-sector manager in Pakistan explained that better ownership of targets by providers can be achieved through a process of dialogue and feedback between those involved in the delivery of services:

‘Let us sit together. Let us see what you can actually achieve and what you need from us. Let me give you all those things. Certain things you will always not be able to give but then you negotiate. You come to a negotiated target… That’s how I think ownership comes in’ (Pakistan – 2).

By contrast, other respondents believed that penalties are necessary to improve performance where a sense of duty and governance structures are weak:

‘I gave you the example of Dr. xxx… she did some great work. She was really the stick. She really made the District TB Coordinators, she made the National Programme Officers, the District Health Officers work… So I think she was very instrumental…’ (Pakistan – 6).

‘In places where the governance is very good and people work in any case, stick may not be necessary. But in places where governance is an issue, stick has to be there. If there is only carrot then it will go to people who are influential and not necessarily deserving. In our case, people will not work if the stick is not there’ (Pakistan – 3).

A health sector manager (Cambodia – 4) further stated that they needed: ‘the carrot, the stick, and scissors’. The scissors, he explained, are needed to cut up contracts of poorly performing workers who have been retained in positions for which they are unqualified. This sentiment was shared by some interviewees in Pakistan (Pakistan – 6, Pakistan – 8, Pakistan – 13) and China:

‘(Low wage) does not influence their motivation or efficiency very much. For example, if they feel they are not paid well and don’t work hard, then they will get fired. So it does not have much direct influence’ (China – 2).

Finally, analysis of views of health sector managers in Cambodia and Pakistan revealed a belief that providers’ perception of the managers’ values and vision can have a large impact on their desire to work with them towards performance goals. Some respondents (Cambodia – 9, Pakistan – 2, 3) felt strongly that providers did not accept monetary incentives and performance goals blindly, but rather questioned values of the manager as well as the manager’s understanding of the local context and needs. Alignment of providers’ values with those of the payer or implementation manager were also considered important in China, but mismatches were perceived to be less prominent as respondents (China – 1, 3) felt that policies were generally considered reasonable by providers.

Issues raised with respect to PBI design and implementation

Lack of adequate resources and skills may prevent agents from achieving performance targets

Health sector managers in all countries suggested that failures to meet the targets set by the organisation (not linked to incentives) were often due to lack of adequate resources – including training, equipment and funds – rather than shortcomings in individual behaviour:

‘Is it because our doctors lack motivation? Or other factors? For example, we need to diagnose some patients, but the equipment for diagnosis is broken, which results in not achieving the targets. This is not caused by individual’s behaviour’ (China – 1).

‘So when we set policy targets, often what is ignored in Pakistan, from my experience of course, is that your capacity is not enhanced accordingly….’ (Pakistan – 2).

Specifically, managers in China (China – 1, 5, 9) expressed concerns with gaps in the infrastructure and the availability of essential equipment, whereas in Pakistan and Cambodia (Pakistan – 2, 3, 6, 12, 13; Cambodia – 3, 4, 9) a lack of skills was identified as a common barrier to the delivery of quality care.

A well-functioning monitoring and evaluation system is crucial to enable performance management; however, reliable and unbiased information is often lacking

Health sector managers in all three countries (Pakistan – 3, 11, 12; China – 10; Cambodia – 3) noted that a well-functioning information system and other monitoring exercises can serve as effective and sustainable performance management tool by itself. As one manager in Pakistan, who strongly associated PBIs with a risk of early truncation owing to dependence on external funding, explained:

‘I do not think that only incentives are a good way to improve performance, especially in a country such as Pakistan. When the donor will go, incentives will go away too. There should be a sustainable solution through motivation… I am strongly against this incentive based system. Government should improve the monitoring mechanism at the district level and they should be accountable’ (Pakistan – 11).

Informants also pointed out that, in order to make accurate judgements on performance, monitoring systems must be useful, information must be reported to the principal accurately and the principal must then fairly use that information as the basis of calculation of rewards. However, many health sector managers noted that reliable assessments of provider performance are often lacking, when information systems are not available at a cost that is feasible for their context, preventing effective implementation of PBI schemes. The information gap was related to both incomplete record keeping and deliberate falsification of records to inflate progress towards targets.

‘His record keeping is not complete [and] if he is writing lies (in the records) even that is not proper so how can I use this information?’ (Pakistan- – 7).

Finally, it was stressed that the way in which performance is tracked and rewarded should be simple and clear for providers to understand. Yet, concerns with the complexity of remuneration schemes emerged. For example, one informant in Cambodia noted:

‘45% of health workers’ pay is made up from various different allowances. They get it in one lump, but they don’t know what these are for. It’s incredibly complicated to try and work out these tiny sums of money’ (Cambodia – 11).

Meritocracy is not always at work in organisations, limiting the extent to which PBIs can be implemented

While managers recognised the importance of monitoring and evaluation systems, some of them cautioned that the lack of meritocracy in the work place may limit the effectiveness of monitoring systems as performance management tools (Cambodia – 2, Pakistan – 3, 12). For example, managers in Pakistan and Cambodia explained that providers are often being rewarded on the basis of factors other than performance, such as political affiliations, family ties or seniority, as the following quotations illustrate:

‘You need a whole reform of public administration, performance based, from a patronage system moving to a more meritocratic system’ (Cambodia – 2).

‘… performance appraisal will be because of political issues, context, and political background. As you know, governance is an issue… those who have not worked for the whole year also have good appraisal and get the same appraisal as the ones who have worked well round the year…’ (Pakistan – 3).

‘I have noticed this in a lot of cases, when somebody stayed there for a long time we don’t really fire that person. We condone a lot of non-achieving of targets because somebody has been there for a long time’ (Pakistan – 2).

Concentration of power and decision-making in some settings may limit ability of health facility managers to action rewards or penalties

Hierarchies, concentration of power or contractual obligations were seen as additional barriers to implement a fair and effective performance management system (Pakistan – 3,12; Cambodia – 4; China – 2):

‘If the director of that hospital wants to discipline any of the people working there they have to get permission from the MOH in Phnom Penh…’ (Cambodia – 4).

‘It’s a little bit hard to improve their motivation or working efficiently, because it depends on the national policies. You cannot just [decide to] give more stipend to TB doctors’ (China – 2).

Although Pakistan implemented a Devolution Plan in 2011 (WHO, 2017a), which led to decentralisation of public health management responsibilities from national entities to the provinces, some respondents noted that authority for performance management has not been devolved enough. At the district level, which comes under provincial authority, a manager who has worked in the public and NGO sectors highlighted that concentration of power constitutes a barrier to implementation of performance management schemes.

‘Unfortunately, for the DHOs (government district health officers), they did not have so many powers for decision-making. For example, they can make decisions about transferring individuals across the facilities, but performance – for example saying that she’s not performing – is not with the DHO’ (Pakistan – 3).

Discussion

This study investigated – from the perspective of senior health sector managers responsible for decisions on human resources and resource allocation – factors apart from or in addition to financial incentives that could encourage better health care provider performance within the health systems contexts and institutions of three countries in Asia.

While a strength of this study is that it adds to the limited literature investigating perspectives of decisionmakers responsible for implementing performance management interventions in LMICs, we recognise that our findings are based solely on the perspective of health sector managers and additional investigation of views of health care providers for triangulation would be useful. In addition, qualitative evaluations of factors associated with the success or failure of PBI schemes in these contexts – although challenging and resource-intensive to conduct – would also provide important information about whether perceptions of health sector managers are in line with actual behaviour of providers. In Cambodia, for example, there is some evidence that the introduction of a financial incentive for midwives to promote institutional deliveries at public health centres and hospitals contributed to a significant reduction in maternal mortality (Ir et al., Reference Ir, Korachais, Chheng, Horemans, Van Damme and Meessen2015). Yet, in all study countries, gaps remain in our understanding of what matters, and why, in the design and implementation of such interventions and this is certainly an important area for future research. We should also note we cannot say with certainty that saturation was achieved, given the complexity of the health sectors in the study countries and the multiplicity of actors involved.

Despite these limitations, our findings provide novel insights about the theoretical assumptions underpinning financial incentives in the health sector as well as potential challenges which should be given consideration when designing and implementing PBI schemes, as summarised in Table 2. First, as described earlier, PBIs are based on the premise that providers respond rationally to, and are primarily driven by, monetary rewards (Laffont and Martimort Reference Laffont and Martimort2009; Cuevas-Rodriguez et al., Reference Cuevas-Rodríguez, Gomez-Mejia and Wiseman2012; Renmans et al., Reference Renmans, Paul and Dujardin2016b; Paul and Renmans, Reference Paul and Renmans2018). However, there was a consistent view among managers from different countries, settings and seniority that monetary incentives alone may not be optimal drivers of performance, although alternative rewards favoured – such as recognition from direct supervisors and career development support – varied between settings and interviewees. In relation to the social science and public health literature on incentives, this finding not only reiterates that materialistic sources of motivation apart from monetary rewards and non-materialistic sources of motivation play an important role, but also indicates that the balance between different sources of motivation is context specific. Consistent with views held by managers in our study settings, the important role of non-monetary incentives in influencing performance, including cultural and community values, has been demonstrated in other LMICs (Dieleman et al., Reference Dieleman, Cuong, Anh and Martineau2003; Mathauer and Imoff, Reference Mathauer and Imhoff2006; Chimhutu et al., Reference Chimhutu, Songstad, Tjomsland, Mrisho and Moland2016) and is in line with literature and conceptual frameworks on health care provider motivation (Deci and Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan1985; Franco et al., Reference Franco, Bennett and Kanfer2002; Paul and Robinson, Reference Paul and Robinson2007); these alternative rewards include gains in social or professional status, receiving recognition of performance in front of colleagues or the wider community, and benefiting from career advancement opportunities. Failing to appreciate the value placed on monetary and non-monetary rewards in different cultural and social settings could hinder the success of a performance management programme; a study of PBIs to support rehabilitation of the health care system following the 2005 earthquake in Pakistan illustrates this (Witter et al., Reference Witter, Zulfiqur, Javeed, Khan and Bari2011).

Furthermore, a striking theme that emerged from some interviews, particularly in Pakistan, was that managers believed that providers’ motivation to perform is influenced by perceptions about the source of funding and how closely the principal’s objectives aligned with the agent’s values. Another example of these factors coming together can be found in the case of female polio immunisation workers in Pakistan, where threats to safety and socio-cultural barriers to participation in polio vaccination campaigns-related to beliefs that these were driven by devious foreign interests – can outweigh utility gained by small incentive payments (Closser and Jooma, Reference Closser and Jooma2013). In this respect, our findings could be interpreted in light of the work of Deci and Ryan, who found that agents undertake a cognitive evaluation of the reward, and if they perceive it to be a form of control by principals, the reward is not as effective at motivating them (Deci and Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan1985). In line with their self-determination theory (Deci and Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan2000), we suggest that the impact of PBIs on motivation of agents may be influenced not only by the amount of incentive payment but also the ‘goal content’, which in our study was related mainly to alignment of agents’ values with the principal’s perceived goals.

Second, our study provides novel insights into the range of contextual variables which may affect, in practice, design and implementation of PBI schemes. Importantly, the idea that performance towards specific work-related targets, rather than years of service or social networks, should be the basis on which rewards are determined, appeared to be inconsistent with cultural and organisational norms according to some interviewees; indeed, it was felt that it would be culturally inappropriate to impose penalties or provide lower rewards to people who had served the organisation for a long time even if their performance was suboptimal. This finding contributes knowledge to other studies which have also highlighted that local culture plays a large part in the conceptualisation of compensation norms (Yeganeh and Su, Reference Yeganeh and Su2011; Magrath and Nichter, Reference Magrath and Nichter2012; Closser, Reference Closser2015) and that perceived ‘fairness’ around who receives most incentive payments is an important determinant of PBI scheme success (Chimhutu et al., Reference Chimhutu, Songstad, Tjomsland, Mrisho and Moland2016).

In terms of the health system ‘readiness’, our study indicates that concentration of power and weaknesses in governance and information systems can leave PBI schemes at risk of breakdown at several stages: principals may not have performance information necessary (at reasonable cost) to determine which agents to reward; when performance information is available it may be ignored in favour of factors such as social ties or years of job experience when deciding on which agents to reward; finally, even when decisions to reward deserving agents are made on the basis of performance information, concentration of power can result in delays to, or overriding of, reward delivery. A breakdown at any of these stages means that performance of agents is not linked directly to monetary incentives, and the motivating impact of the potential to receive PBIs is hindered from acting as intended (Mathauer and Imhoff, Reference Mathauer and Imhoff2006). Notably, structures for governance and the collection of relevant information to support PBIs were considered essential in all settings, but found to be weak in Pakistan and Cambodia.

In addition, a critical consideration for the use of PBIs is concentration of power within the health system and at what level a system of rewards can be implemented. Ideally, PBIs should be implemented concurrently with reforms in health system financing that allow for greater autonomy at less central levels of government, providing more decision-making power to direct local managers as well as higher level of accountability (Basinga et al., Reference Basinga, Gertler, Binagwaho, Soucat, Sturdy and Vermeersch2010). Recognising these challenges, Cambodia is currently implementing reforms that increase administrative devolution. One example is the recent conversion of one quarter of Operational Districts and Provincial Hospitals to the status of Special Operating Agency. This is a new administrative approach which provides local health managers with greater autonomy in decisionmaking and more flexibility in budget allocation, including discretion over the allocation of funding for staff incentives through internal contracting arrangements (WHO, 2015b). As our study and others indicate (Mabuchi et al., Reference Mabuchi, Sesan and Bennett2018), empowerment of local managers is crucial to improving health workers performance.

Last but not least, some managers pointed to the lack of adequate infrastructure, resources or funds as important drivers of poor performance. Again, this finding resounds with studies in Cambodia and other LMICs, which found a strong correlation between basic income and performance, in addition to the well-known issue that low salary is a major barrier to attract and retain qualified health workers in the public sector (Henderson and Tulloch, Reference Henderson and Tulloch2008; Chhea et al., Reference Chhea, Warren and Manderson2010); as a number of previous studies documented, low salary levels can also encourage predatory practices, such as pilfering supplies from health facilities, charging informal fees or engaging in dual practice (Jan et al., Reference Jan, Bian, Jumpa, Meng, Nyazema, Prakongsai and Mills2005; Akwataghibe et al., Reference Akwataghibe, Samaranayake, Lemiere and Dieleman2013). In such contexts, the award of financial or other incentives may provide a temporary fix to the problem, but is not going to address the key structural drivers. Rather, policy reforms designed to provide an acceptable salary retribution at all levels in the health sector, from senior managers to community nurses, would constitute a more effective and long-term solution to improve health workers performance and the quality of care. If countries with limited finances for health sector development, such as Cambodia, will continue to experience high rates of economic growth as in recent years, there may be increasing prospects to support the health workforce with an acceptable level of regular retributions.

Conclusion

In many LMICs countries, basic salaries in the public sector are still inadequate to motivate health workers. In such contexts, PBIs often account for a significant fraction of the monthly salary (Khim, Reference Khim2016), and remain a popular approach to address wider structural gaps, with some evidence of positive outcomes. Yet, the introduction, design and implementation of health care provider performance management schemes requires careful consideration of the range of social, cultural and health system factors which may affect appropriateness of interventions and policy outcomes. Our study contributes new evidence on some of these critical issues – such as the relative importance of monetary and non-monetary rewards, the availability of objective information to determine reward allocation, and decision-making power held by health system managers; as described, these practical and theoretical issues may influence not only the successful functioning of PBI schemes in the study contexts and elsewhere, but also challenge fundamental assumptions about the value of financial incentives, and, ultimately, what drives human behaviour. Most strikingly, our study indicates that managers in our three study countries felt that that PBIs are not an adequate means to motivate health workers on their own, and therefore continued research on alternative approaches to improve performance of health care professionals remains an urgent need.

Acknowledgements

We our grateful to the interviewees for their participation in this study.