1. Introduction

The objective of this paper is to propose a new way of thinking about unmet need for health care which can in turn guide analysis of unmet need in terms of potential data sources and analytic approaches.

Unmet need for health care is a concern from many perspectives including individual (e.g., potential pain and disability), policymaking (i.e., planning health care to meet the needs of the population) and societal (e.g., informal care burdens, economic inactivity due to untreated health care needs). In addition, it is important to consider unmet need when determining the effects on demand and service costs of any changes in eligibility criteria, for example, when financial barriers to care are altered (Wren et al., Reference Wren, Connolly and Cunningham2015). Yet there has been relatively little analysis of unmet need for health care services in the European or wider international setting. It remains a challenge to pin down what types of unmet need can and should be addressed by health care policymakers, and how to go about identifying and quantifying unmet needs.

One difficulty in measuring unmet need accurately is the absence of universal agreement on how to define it. There has been some progress made in recent literature in teasing out alternative types of unmet need (Allin et al., Reference Allin, Grignon and Le Grand2010) making useful contributions to the way in which unmet need is conceptualised and analysed. As a next step, this paper considers what happens to unmet need (of different types) over time. By introducing a dynamic perspective, alternative trajectories for unmet needs are outlined and discussed with a view to improving the focus, and policy applicability, of empirical research in this field.

To set the context for re-thinking unmet need in health care, Sections 2 and 3 examine the complexity of the concept and existing methodologies for analysing unmet need for health care services. Section 4 introduces a dynamic perspective to the conceptualisation of unmet need, outlining three potential trajectories for unmet needs over time. Section 5 considers the practical implications of the revised way of thinking about unmet need, proposing new avenues for empirical analysis and Section 6 concludes.

2. Definitions: need and unmet need

There is no universally accepted definition of ‘unmet need’ and the term is used differently by different commentators. A useful starting point is consideration of the concept of need.

2.1 Defining need

Health care need is an elusive concept and one that has been subject to much discussion and debate (Acheson, Reference Acheson1978; Culyer and Wagstaff, Reference Culyer and Wagstaff1993; Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Young, Butow and Solomon2013). Need can be associated with an individual's level of ill-health, although this definition is often considered too narrow since it would likely exclude preventive care (Allin et al., Reference Allin, Masseria, Sorenson, Papanicolas and Mossialos2007) and also fails to consider whether the ill-health is amenable to health care. An alternative view relates health care need to capacity to benefit from health care. In this view, need is assumed to exist when there is an effective treatment (Gillam, Reference Gillam1992) or potential health gain (Culyer and Wagstaff, Reference Culyer and Wagstaff1993). There is some consensus that in principle, capacity to benefit is the more appropriate definition when considering need (Culyer and Wagstaff, Reference Culyer and Wagstaff1993). However, measuring need by level of ill-health is commonly used because of ease of measurement. Measures of health status are well developed and easily accessible, while measuring capacity to benefit is highly complex (Allin et al., Reference Allin, Masseria, Sorenson, Papanicolas and Mossialos2007).

2.2 Defining unmet need

Turning to unmet need, many definitions in the literature implicitly interpret need in terms of capacity to benefit from health care. Reeves et al. (Reference Reeves, McKee and Stuckler2015) defined unmet need as being unable to obtain care when people believed it to be medically necessary. Building on work from Carr and Wolfe (Reference Carr and Wolfe1976), a number of commentators have defined unmet need as the difference between services judged necessary to deal appropriately with health problems and the services actually received (Sanmartin et al., Reference Sanmartin, Houle, Tremblay and Berthelot2002; Pappa et al., Reference Pappa, Kontodimopoulos, Papadopoulos, Tountas and Niakas2013).

Allin et al. (Reference Allin, Grignon and Le Grand2010) more explicitly build on the literature on the definition of need, defining unmet need as arising when an individual does not receive an available and effective treatment that could have improved his/her health. While some unmet need is acceptable since resources are scarce, what is of concern is whether unmet need is inequitable or systematically related to socioeconomic or other personal characteristics. The authors further unpick the definition of unmet need by outlining five types:

(1) Unperceived unmet need: individuals are not aware of this unmet need.

(2) Subjective, chosen unmet need: individual perceives a need but chooses not to demand available health services.

(3) Subjective, not-chosen unmet need: individual perceives a need for, but does not receive, health care because of access barriers.

(4) Subjective, clinician-validated unmet need: individual perceives a need for and accesses health care, but does not receive treatment that a clinician judges is appropriate (e.g., treatment of a primary care complaint at an emergency department rather than in an ambulatory care setting).

(5) Subjective unmet expectations: individual perceives a need for and accesses health care, but does not perceive the treatment to be suitable.

These categorisations are useful in highlighting unmet need as a complex, multi-dimensional concept that may require alternative approaches to identifying and analysing different aspects of the concept. This key point is taken up and advanced further in Section 4 where a dynamic perspective on unmet need is adopted.

3. Background: methods for analysing unmet need

Different methods have been applied to analyse unmet need in the context of existing definitions and categorisations of unmet need. Much of the early work assessed unmet need through utilisation models for specific conditions using clinical examinations (Carr and Wolfe, Reference Carr and Wolfe1976). More recently, analysis has distinguished between clinical and subjective approaches (Allin et al., Reference Allin, Grignon and Le Grand2010). The former relies on a clinical assessment of whether an individual did not receive appropriate care while the latter relies on individuals' subjective assessments that they have not received the care that they need.

Allin et al. (Reference Allin, Grignon and Le Grand2010) and Cavalieri (Reference Cavalieri2013) identify a number of reasons for why subjective measures of unmet need may be superior to clinical measures in assessing unmet need. First, subjective measures are more amenable to applied research (e.g., standardised questions on unmet needs are included in many periodically conducted national health care surveys). Second, subjective assessment of unmet need is consistent with an assumption that the patient is the best judge of his/her health status and of whether he/she has received appropriate health care. However, subjective measures are also associated with shortcomings, for example, neglecting unperceived (but clinically relevant) unmet health needs (Cavalieri, Reference Cavalieri2013).

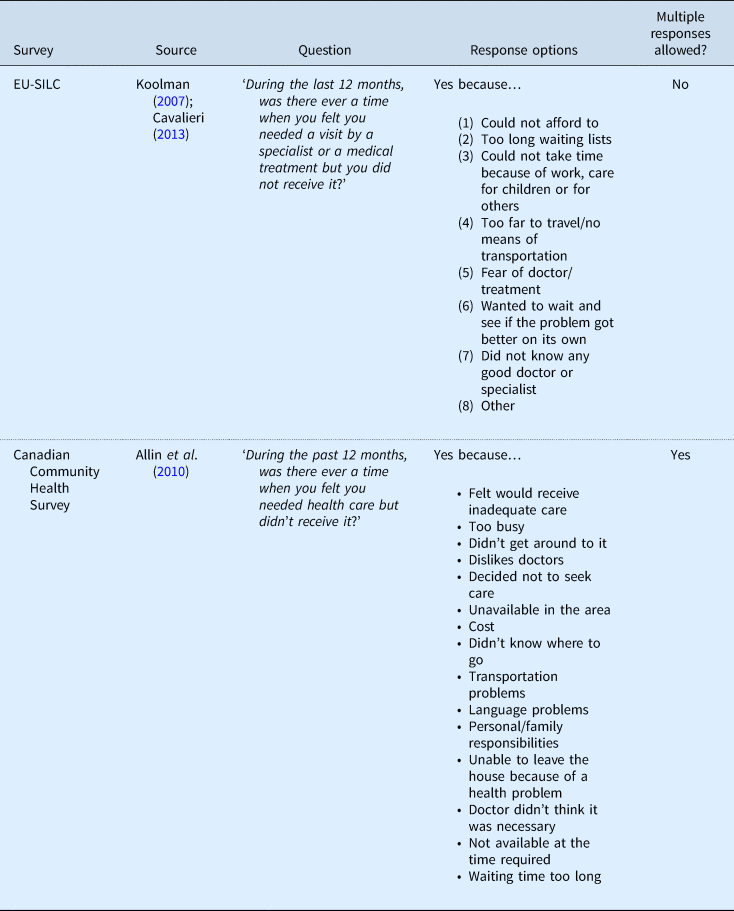

Much of the research on unmet need has adopted general survey questions to provide an overview of the extent and potential causes of self-perceived unmet health care needs (e.g., Allin et al., Reference Allin, Grignon and Le Grand2010; Washington et al., Reference Washington, Bean-Mayberry, Riopelle and Yano2011; Pappa et al., Reference Pappa, Kontodimopoulos, Papadopoulos, Tountas and Niakas2013). There are similarities in the types of questions, and in the response options, across these surveys. For example, Table 1 outlines the questions and responses used in the Canadian Community Health Survey and in the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) instrument.

Table 1. Sample of survey questions on unmet need

An alternative approach to measuring unmet need uses survey data to identify those with a need for health care based on their health status and subsequently examines their use of health care services (Alonso et al., Reference Alonso, Orfila, Ruigomez, Ferrer and Anto1997; Vlachantoni et al., Reference Vlachantoni, Shaw, Willis, Evandrou, Falkingham and Luff2011). Vlachantoni et al. (Reference Vlachantoni, Shaw, Willis, Evandrou, Falkingham and Luff2011) used a number of UK-based surveys to identify respondents who had difficulty in performing activities of daily living. A person was defined as having unmet need for social care when they had one/more of these difficulties but did not receive help (formal or informal) with specific tasks. While potentially informative, caution is required in interpreting results which equate self-reported poor health status to need for health care (Collins and Klein, Reference Collins and Klein1980) without considering the range of factors contributing to health care need and subsequent demand for health care, discussed in more detail below.

4. Re-thinking unmet need

Taking into account the available methods for analysing unmet need, this section considers why more clarification is needed on its definition. After all, in subjective assessments of unmet need, varying proportions of survey respondents in a number of different countries provide responses to questions on unmet need (e.g., Chaupain-Guillot and Guillot, Reference Chaupain-Guillot and Guillot2015). Furthermore, respondents are able to indicate the primary reasons for those unmet needs. However, there are concerns that there are inconsistencies in the way in which the questions are interpreted (Connolly and Wren, Reference Connolly and Wren2017). It is also difficult to determine what should be the appropriate policy response without more information on what has happened to the unmet needs over time. Extrapolating from a representative survey to a population, what does it really mean to say that X% of a population have had an unmet need for, say, general practitioner care in the last 12 months? How serious are those unmet needs? Do those needs remain unmet? It is hard to believe that in each of those cases the need remains unmet, that no health care has been made available since the need arose and that all of those people have untreated illnesses. It is more likely that over time some of them have recovered without needing treatment, others have sought emergency treatment, others are living in pain and discomfort for ongoing chronic complaints, others have been assessed and are on waiting lists and so on. Without knowing what happens to a stated unmet need over time, it is difficult to know how best to respond to it (if at all in the case of needs that disappear).

On the other hand, methods that are based on clinical assessments of whether or not individuals received appropriate care also miss important information on how needs are dealt with over time. Perhaps a need for health care was perceived by the individual but they chose not to seek care, or they sought care and are on a waiting list, or they are waiting to see if the problem gets better before seeking care, etc.

Thus, one of the challenges in examining unmet need using existing approaches concerns the limited scope for translating research findings into policy recommendations. In most cases, unmet needs are examined at one point in time without consideration for how long those needs remain unmet. It is entirely possible that a need identified as unmet at one point in time may resolve itself without any health care intervention, or, if left unmet, may worsen, or may be addressed and resolved at a later date. Analysis taken at one point in time cannot distinguish between these (and other potential) scenarios and yet the scale and nature of unmet need, and appropriate policy response, may be different in each case. For example, in their study of unmet need in Canada, Sanmartin et al. (Reference Sanmartin, Houle, Tremblay and Berthelot2002) acknowledge that their survey question is unable to distinguish between non-use at any time and non-use in a timely manner thereby restricting the scope for making policy recommendations.

This section re-thinks unmet need from a dynamic perspective, considering what happens to unmet needs over time and proposes three alternative trajectories for unmet need. By considering what happens to unmet needs, we can in turn identify new ways of getting more information on the nature and scale of unmet need in a health care system, which can ultimately help to identify appropriate policy responses.

4.1 Distinction between need and demand

As a first step to re-thinking unmet need, the categories presented by Allin et al. (Reference Allin, Grignon and Le Grand2010) remind us that needs for health care are not the same as demand for, or use of, health care.

A number of theoretical models focus on the concept of health care demand (e.g., Grossman, Reference Grossman1972) including need for health care as one, but only one, of the determinants of demand. One of the most frequently adopted models is Andersen's behavioural model of health services use (Andersen and Newman, Reference Andersen and Newman1973; Aday and Andersen, Reference Aday and Andersen1974; Andersen, Reference Andersen1978; Andersen, Reference Andersen1995, Reference Andersen2008) which considers how peoples' use of health services is a function of their need for care and a host of other factors including individual and health system characteristics (Andersen, Reference Andersen1995) (Figure 1). Thus, the model can be useful for teasing out factors that drive demand for health care, identifying why a need for health care may, or may not, be translated into an associated demand for (i.e., request to use) health services.

Figure 1. Andersen's behavioural model of health services use (phase 4).

4.2 What happens to needs?

The distinction between need and demand/request to use helps us to think about unmet need in a different way. For a health care provider to respond to a given need (i.e., to assess, treat or refer), the need must first be converted into a demand for health care. Needs that are perceived but not presented to a health care provider (for whatever reason) remain under the radar of, and cannot be addressed by, the health care system.

Thus, re-thinking unmet need raises a core concern: what happens to a given need? This core question is broken down into two parts for ease of presentation:

(A) Does a given need get converted into a demand?

(B) What happens to that need over time (i.e., if not converted into demand, what happens to that need; if converted into demand, what happens to that need)?

To date, typical survey questions on unmet need appear to focus on needs that are perceived but not translated into demand, captured in Part A above. This is illustrated in the response options to the question on unmet need in the EU-SILC instrument (Table 1). The response options (with the exception of ‘other’ and ‘waiting lists were too long’) each assume that need was not converted into demand. In other words, the person did not present the need to any health care provider because they could not afford to, could not take time off work, fear of doctor/treatment, waiting to see if problem got better or they did not know any good doctor/specialist. Interpretation of the response option ‘waiting lists were too long’ is ambiguous: the survey respondent could interpret this in terms of perceived waiting lists (i.e., he/she did not seek medical attention because of perceived long waiting lists, in this case need is not converted into demand), or objective experience of waiting lists (i.e., he/she tried to access care but found waiting lists to be too long, in this case need was converted into demand).

However, when an individual indicates that they did not seek medical attention (i.e., need was not converted to demand) for a perceived health care need, this begs the question: what happens to that need over time? Does the problem get ‘better on its own’ (EU-SILC, Eurostat, 2016), does it worsen, diminish or stay the same?

Where the problem persists or worsens, it is reasonable to expect that in many cases the individual will, at some point in the future, present to a health care provider (e.g., a stomach pain that ends up as an emergency appendectomy; a chest infection that develops into pneumonia, etc.). Thus, a core stumbling block in the definitions and much of the empirical analysis of unmet need to date is the (implicit) absence of a dynamic perspective. Where unmet needs are measured at one point in time, the longer-term consequences of what happens to those various needs are not considered and yet this information is important for quantifying and responding to unmet need in a health care system.

4.3 Re-thinking unmet need: introducing a dynamic perspective

4.3.1 Alternative trajectories of unmet need

Taking a longer time perspective requires us to examine in more detail the types of perceived needs that (a) remain completely under the radar of the health care system over time, or (b) are presented now, or at a later date, for attention from a health care provider. By considering what ultimately happens to perceived needs, three different trajectories can be identified for unmet needs. These are described in detail in the next section: (1) non-use at any time; (2) delayed (and/or diverted use); (3) sub-optimal use.

4.3.2 Underlying assumptions

Before expanding on the proposed trajectories of unmet need, this section sets out some core assumptions to this discussion. First, in line with the approach of Allin et al. (Reference Allin, Grignon and Le Grand2010), the focus is on perceived rather than unperceived needs. While unperceived needs are important to address, these fall into the well-established field of preventive health care; policies required to increase people's awareness of their own health problems will most likely include public health education, promotion and screening programmes.

Second, in line with the literature on unmet need, need is defined in terms of capacity to benefit from health care. This ensures the focus is on needs that are amenable to health care and that the individual can benefit from the relevant health care intervention.

Third, a given level of medical technology is assumed. In practice, medical technology is continually advancing and this expands the range of conditions that are amenable to health care over time. However, for most health systems, it is reasonable to assume that there is a time lag between advances in technology and expansion of conditions that can be treated (e.g., due to budget constraints, licensing processes for new drugs/procedures, training requirements, etc.). In the short-medium term, it is assumed that there is a limit on the needs that are amenable to health care given current technologies. This makes it easier to quantify unmet needs in the absence of moving targets of what can be considered needs that are amenable to health care.

Fourth, the focus is on health care systems that are governed by widely acceptable principles, for example, in terms of equity (e.g., equal access to health care) and health care integration (i.e., health care system seeks to deliver care at the most appropriate time, in the most appropriate setting).

4.3.3 Non-use

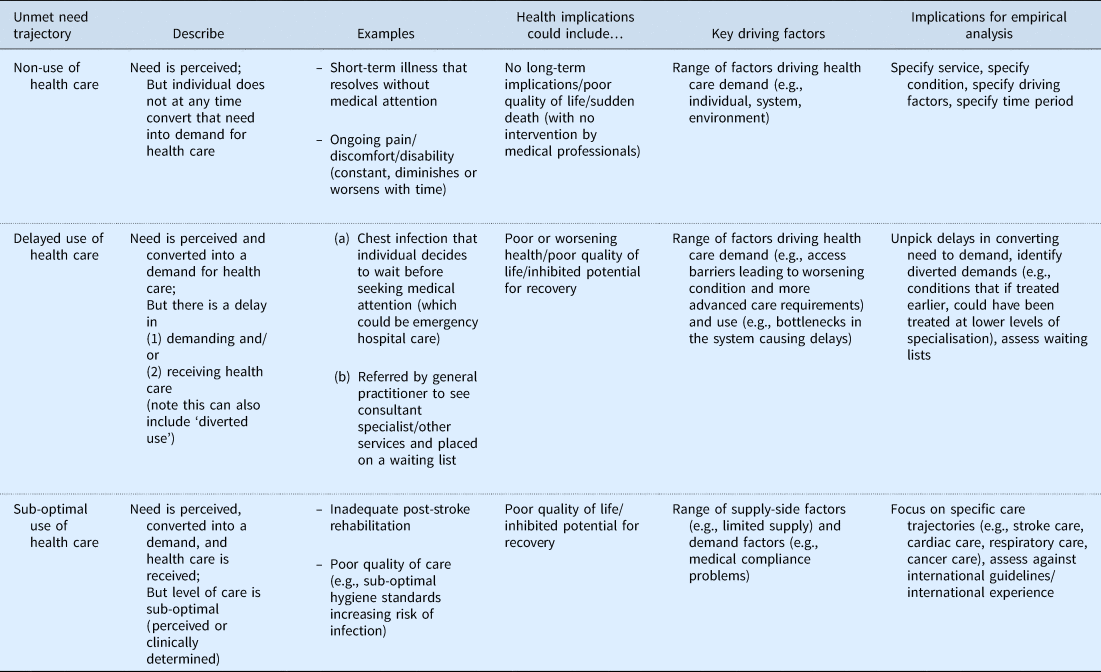

Table 2 summarises the three proposed trajectories of unmet needs. Non-use refers to a scenario where a need is perceived, but the individual does not at any time convert that need into a demand for health care. Note how this differs from existing survey analysis which focuses on non-use at one point in time or specified time period (e.g., last 12 months).

– It is easy to think of examples of perceived needs that are amenable to health care but which never come to the attention of a health care provider such as minor complaints that disappear with time (e.g., back pain, mild viruses, etc.). Other minor complaints that do not disappear but which do not worsen may just be ‘put up with’ and managed by over-the-counter medicines (e.g., infrequent migraines). There may be other complaints that worsen rather than diminish with time but still do not get presented to a health care provider. For example, elderly people living with disabilities and needs for social care but factors such as perceived inadequate supply, lack of transport, etc., may prevent the individuals from seeking out the services. Using data from England, Vlachantoni et al. (Reference Vlachantoni, Shaw, Willis, Evandrou, Falkingham and Luff2011) found that more than 60% of respondents who reported difficulties with dressing and bathing did not receive any kind of support (at least during the time period covered by the study).

– The long-term implications of these unmet needs depend on the nature of the condition. Unpicking in more detail the types of conditions that remain under the radar of the health care system over time is central to developing appropriate policy responses. Moreover, the extent to which there are people living with ongoing pain and disability that are not picked up by the health care system has important social and economic implications (e.g., informal care burden, economic activity, social involvement).

Table 2. Trajectories of unmet need

4.3.4 Delayed use

Delayed use refers to a scenario where a need is perceived and converted into a demand for health care, but there is delay in receiving care. The delay can occur at either or both of the following times:

(a) delay in demanding health care (e.g., the person waits to see if the problem gets better before seeking care);

(b) delay in receiving care (e.g., service availability is limited and the patient is placed on a waiting list).

This trajectory can also encompass examples of ‘diverted’ use, whereby an individual has a perceived need that could be appropriately treated, for example, in a primary care setting, but because of delay in seeking or receiving care, the need increases and ultimately requires a more advanced level of health care.

Delayed care is expected to have a detrimental effect on health and quality of life with the impact varying by condition, patient characteristics and length of delay. It is also possible that delayed care could inhibit a patient's potential capacity to benefit from a given medical intervention. Koopmanschap et al. (Reference Koopmanschap, Brouwer, Hakkaart-van Roijen and van Exel2005) identify a number of ways in which waiting times may adversely impact on a patient's health status. For example, a patient's health may deteriorate while waiting but the health loss is reversible; alternatively, the wait time may not only affect health while waiting but also impact on treatment efficacy (Koopmanschap et al., Reference Koopmanschap, Brouwer, Hakkaart-van Roijen and van Exel2005).

Priorities for research into delayed care include unpicking the reasons for delays in seeking care (and for what conditions) and in this context also examining patterns of diverted demand, for example, drawing on the literature on avoidable hospitalisations whereby patients presenting to acute emergency departments with ambulatory care-sensitive conditions may represent cases of diverted demand (e.g. Nolan, Reference Nolan2011). Analysis of waiting lists and determining thresholds for acceptable waiting times for different conditions and patient characteristics would further contribute to the analysis of delayed demand.

4.3.5 Sub-optimal use

Sub-optimal use refers to a scenario where a need is perceived and converted into a demand, and health care is received, but the care is sub-optimal in some way. This trajectory ties in closely with categories 4 and 5 identified by Allin et al. (Reference Allin, Grignon and Le Grand2010) whereby the judgement about the quality of the care can be subjective (type 5) or clinically validated (type 4).

5. Implications for applied research

As discussed by Allin and Masseria (Reference Allin and Masseria2009), unmet need is multi-faceted and it is unlikely that a single indicator or method of measurement will capture all aspects of unmet need. The above proposals for re-thinking unmet need support this view. Different types of analyses (i.e., data sources, analytic techniques) have a role in teasing out the alternative trajectories of unmet need. This section considers some generic guidelines for future analyses of unmet need in a health care system.

5.1 Non-use and delayed use trajectories: first best research options

Much of the previous research on unmet need (especially that using survey data) identified an unmet need as occurring when there was a perceived need for health care but the health care was not received at a given point in time or specified time period. As discussed, very often these data do not give enough information to inform policy. Re-thinking unmet need from a dynamic perspective distinguishes needs that are never translated into demands for health care from those that are presented but with delays and/or diversions. This approach has implications for how unmet need is identified and quantified within a health care system.

Given the importance of the dynamic perspective in determining the likely trajectories (and implications) of different unmet needs, it is clear that more longitudinal research is needed in this area. Longitudinal studies that are specifically designed to track health care-seeking behaviours over time are best placed to distinguish between the non-use and delayed use trajectories. For example, the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA) collects data on individuals aged 50 and over until death (interviews are conducted with family members and friends of TILDA participants who have died since the study began). There has been some analysis of unmet need for community services in the last year of life using TILDA (May et al., Reference May, McGarrigle and Normand2017), but there is potential to extend the analysis to focus on need and utilisation patterns in the years up to and including the last year of life. Such studies could greatly contribute to the understanding of (a) the extent, nature and reasons behind needs that are never presented to the health care system (i.e., the ‘non-use’ trajectory), and (b) the extent, nature and reasons behind delays in the presentation and/or treatment of health care needs (i.e., the ‘delayed use’ trajectory).

In addition, many health care systems have the capacity to link datasets and this presents an opportunity to examine links between presentation of health care needs and subsequent treatment of those needs. For example, more studies could follow the approach of linking survey data on self-perceived needs with subsequent health care-seeking behaviour (e.g., utilisation data) such as that undertaken by Long et al. (Reference Long, King and Coughlin2005) and Ronksley et al. (Reference Ronksley, Sanmartin, Quan, Ravani, Tonelli, Manns and Hemmelgarn2013) to explore in more detail the patterns of delayed and diverted health care use. Long et al. (Reference Long, King and Coughlin2005) linked US survey data with Medicaid claims data to assess the relationship between unmet need for doctor care and prescription drugs and subsequent health care use (Long et al., Reference Long, King and Coughlin2005). Ronksley et al. (Reference Ronksley, Sanmartin, Quan, Ravani, Tonelli, Manns and Hemmelgarn2013) linked the Canadian Community Health Survey with hospitalisation data to see if self-reported unmet need is associated with hospital admissions.

5.2 Non-use and delayed use trajectories: second best research options

It is likely that cross-sectional survey data will continue to be a core resource for analysing unmet need at least in the short term in the absence of appropriate longitudinal studies in many countries. Given that the most commonly applied survey questions on unmet need fail to take a dynamic perspective, the available data from these surveys are not able to distinguish between needs that are never presented to a health care provider (for whatever reason) and needs that are ultimately presented to a health care provider following a delay (for whatever reason). Without further investigation of these two trajectories, the policy implications remain unclear. The reasons given for non-use and delayed use may in fact be relatively similar giving rise to similar policy responses (e.g., remove access barriers, increase supply, etc.), or perhaps some access barriers may be more applicable to non-use than to delayed use and vice versa. Moreover, policy responses may be different according to the number of cases of non-use or delayed use and the types of needs that are not being met in these trajectories.

Empirical analysis is needed to more accurately map and quantify the non-use and delayed use trajectories, to specifically focus on information that better informs the policy process. Adjustments to standard cross-sectional survey questions are suggested, along the lines of those outlined in Tables 3 and 4. It is important to note that any adjustments to cross-sectional survey questions that attempt to introduce a dynamic perspective will necessarily increase the level of complexity of those questions. The questions in Tables 3 and 4 have been prepared in the knowledge that existing questions on unmet need are typically included in large-scale well-established surveys where scope for adding new questions may be limited.

Table 3. Proposed survey questions on delayed and non-use of health care

Table 4. Optional additional survey questions on delayed and non-use of health care

The focus of the questions in Table 3 is on the trajectories of unmet need that are most amenable to a cross-sectional survey setting, namely, delays in seeking care [i.e., part (1) of the ‘delayed use’ trajectory], and non-use of health care (for a specified time period). This acknowledges that other sources of data will be more appropriate for unpicking the other types of unmet need [e.g., waiting list data can be analysed to explore delays in receiving care (i.e., part (2) of the ‘delayed use’ trajectory)]. By narrowing the focus of these surveys to specific aspects of unmet need, the aim is to increase the policy relevance of the findings. The questions are revised with a view to distinguish between needs that have not been presented to a health care provider and those that are presented, but with some form of delay. Thus, more information is required on the service being sought, the conditions being presented/not presented and the trajectory of the need over a specified time period.

Questions in Table 3 that are highlighted in bold are proposed as core questions while those in regular font would provide useful, but possibly not essential, additional information. As a first step, even using questions 1 and 6 could be considered in the next iteration of a large survey such as EU-SILC to examine the distinction between non-use and delayed demand (within a specified time period).

It is important to note that these proposed revisions are in draft form and as with all new survey questions these would need to be piloted.

There are also some limitations to these survey questions that require further attention:

– The questions are aimed at distinguishing between delays in seeking care [i.e., part (1) of the ‘delayed use’ trajectory], and non-use of health care (for a specified time period). Ideally, these questions would more accurately capture the distinction between delayed demand and non-use at any time. These questions are framed to suit existing cross-sectional surveys on unmet need such as EU-SILC, where the reference time period is typically one year (i.e., ‘During the last year, was there…’). Longer time periods could be considered but problems of recall would inhibit this approach. Alternative survey instruments might be able to capture longer time periods [e.g., post-death interviews with relatives of deceased patients as used in the field of palliative care (Brick et al., Reference Brick, Normand, O'Hara and Smith2015)]. However, as discussed, the most appropriate methods to capture the dynamic nature of unmet need are longitudinal studies, ideally with links to administrative data on utilisation.

– Even with a reference time period of one year, recall may be problematic. Studies on accuracy of self-reported utilisation find evidence of under-reporting for recall periods longer than 12 months, and the optimal recall period for routine doctor visits is estimated to be six months or less, with longer periods, up to 12 months for less frequently used health care services (e.g., hospital admissions) (Bhandari and Wagner, Reference Bhandari and Wagner2006). Moreover, the drawback to shortening the time period to, for example, six weeks, would give less opportunity for finding out how long someone might delay seeking care and could over-estimate ‘non-use’ cases.

– Whatever the time period, an individual may experience more than one case where a need is not met within that time period, or where there is a delay in the need being presented to a health care provider. This is currently not allowed for in the proposed questions in Tables 3 and 4. Where space permits, future survey questions could allow for more than one episode of non-use or delay in seeking care.

– While the focus of the proposed (and existing) survey questions is on use of health care services, it is important to remember that use of health care is a process indicator, a means to improving health status. This distinction is captured in the study by Alonso et al. (Reference Alonso, Orfila, Ruigomez, Ferrer and Anto1997) which examined the impact of unmet need on subsequent mortality among older people in Spain.

5.3 Delayed use and sub-optimal care trajectories: other research options

Re-thinking unmet need with a dynamic perspective points to additional sources of information that may not previously have been considered as relevant for analysis of unmet need. Analysis of avoidable hospitalisations, unplanned use of emergency hospital services for ambulatory-sensitive conditions, and prolonged hospitalisations can capture elements of diverted use of health care, while examination of waiting lists can help to quantify the extent of delayed use.

Identifying sub-optimal care is challenging given the variations in treatment protocols for different conditions within and across health care systems. One option is to assess care delivered against internationally agreed, evidence-based standards, where these are available. Recent examination of the quality of care available to stroke survivors in the Irish health care system when compared with international best practice finds important shortfalls in care, with negative implications for quality of life and independence (Wren et al., Reference Wren, Gillespie, Crichton, Smith, Kearns, Parkin, Hickey, Horgan and Wiley2014).

6. Discussion and conclusions

Available literature on unmet need shows this to be a complex concept with varying definitions. Taking the lead from Allin et al. (Reference Allin, Grignon and Le Grand2010), analysis of unmet need requires different approaches to examine the nature and extent of unmet need in a health care system. Introducing a dynamic perspective takes the discussion further by considering three alternative trajectories of unmet needs: non-use, delayed use, sub-optimal use. From this dynamic perspective, it is expected that much of what is labelled as ‘unmet need’ in current discussions of health care utilisation is in fact, delayed or diverted use given that existing measures are more likely to pick up on needs for care that have not yet been dealt with rather than true non-use. This clarity is not merely a matter of semantics but helps to focus attention on the reasons for, characteristics of, and scale of delays in seeking and delivering appropriate health care to those who need it. Delays can be seriously detrimental to people's well-being and can also lead to more, and more expensive, health care being required. Research that more clearly examines delayed health care use has the potential to be more informative for policymakers than research that conflates non-use with delayed use.

The alternative trajectories highlight the importance of longitudinal research in this area, but also identify alternative data sources and analytic methods that can each contribute to unpicking unmet need in a given health care system. Nevertheless, this mode of re-thinking unmet need is not without its limitations and the following outlines some key complications.

Probably the biggest limitation concerns the challenge in distinguishing non-use from the other two categories. Ideally, to get at true non-use, an individual's self-reported unmet need should be followed from its inception to the end of that individual's life. In practical terms, it is more likely that unmet needs are considered over much shorter time periods. Therefore, analysis over a short time frame can only expect to pick up a temporary distinction between non-use and delayed use (i.e., some of those identified as being non-users, by whatever means, might in time be re-categorised as delayed users). While this is a drawback, the solution to the problem is to work on improving data sources and analytic techniques rather than ignoring the distinction between true non-use and delayed use in the underlying construct of unmet need. At the very least, the re-thinking of unmet need in this paper underlines the importance of specifying the time period over which non-use is examined, something that has not been consistently applied in the current literature.

Thus, while in theory the non-use trajectory is independent from the other two trajectories, in practice there may be overlaps between the three trajectories. This paper argues that what is important is to understand that there is a distinction between non-use and delayed use, that these are different things and describe different ways of interacting with the health care system, and that unless we strive to examine them, we cannot know if the policy responses required are the same or different. Similarly, it is not suggested that the delayed use and sub-optimal use trajectories are mutually exclusive. In some circumstances, it may be hard to distinguish the two trajectories, where the delay itself is the reason for sub-optimal care. For example, delayed rehabilitation following a stroke (a form of delayed care) is in itself regarded as sub-optimal care because in the case of stroke particularly, recovery can be inhibited by the delay (Bernhardt et al., Reference Bernhardt, Indredavik and Langhorne2013).

Second, within the category of non-use, there is a mixed bag of health complaints, some which disappear over time without formal medical intervention and others which have the potential to seriously impinge on a person's well-being. Are these distinctions important from a policy perspective? In principle, yes, because in broad terms the first group are not living with ill-health and do not, ex post, need health care (but had misperceptions about the need for care), while the second are living with ill-health and health care services should be available for them. In practice, it is more difficult to create appropriate access measures that can weed out necessary from unnecessary health care demand. For example, available evidence on out-of-pocket payments (i.e., paying for health care at the point of use) indicates that people are not always the best judges of what health care they need and that out-of-pocket payments can deter both effective and ineffective treatments (Shapiro et al., Reference Shapiro, Ware and Sherbourne1986). However, as above, despite these challenges, this is not a reason to avoid describing the complexity of the underlying construct of unmet need but rather to find out more about the characteristics of those who do not seek health care, for what types of complaints, and with what consequences.

Third, the focus on perceived needs requires further attention. There is evidence that individuals perceive needs in systematically different ways and this may have implications for interpretation of data and policy recommendations. For example, drawing on US survey data that include subjective and clinical measures of different health conditions, Choi and Cawley (Reference Choi and Cawley2018) found that respondents with higher levels of education were more accurate in reporting their health status than those with lower levels of education.

Fourth, the assumption that medical technologies are given is difficult to marry with a framework of unmet need that emphasises the importance of a dynamic perspective. This assumption could be relaxed if policymakers are interested in how the conversion of needs into demands for health care responds to changes in technologies.

Fifth, the assumption that need is defined in terms of capacity to benefit may not always hold. Where empirical analysis focuses on perceived needs without any clinical validation, those perceived needs may or may not be amenable to health care.

Lastly, the proposed framework for re-thinking unmet need does not change the fact that in any health care system, with limited health care resources, there will always be some level of unmet need. Even in a system with zero costs of accessing health care, with health care suppliers located in line with local needs, and with integration across the system ensuring appropriate care at the most appropriate level, there will likely be some unmet need. Such unmet need can arise from factors such as individual choices about utilisation or health complaints that are not amenable to current health care. Therefore, a central question for health care policymakers is what unmet needs can be addressed within current resource and medical technological constraints. In a related point, health care is a broad term that in some cultures encompasses interventions that in others are considered outside of the formal medical approach, giving another reason for why unmet need can vary from one country to another.

Overall, this paper offers a new way of thinking about unmet need for health care with a view to advancing understanding of unmet need in a health care system and guiding future empirical analysis to generate policy-relevant findings. In re-thinking unmet need, the importance of adopting a dynamic perspective is emphasised. By considering the simple question of what happens to a health care need, three unmet need trajectories are proposed. Different data sources and methods are required to unpick these trajectories, and proposals for empirical analysis of the trajectories have been made.