Introduction

A number of countries are considering whether medical savings accounts (MSAs) are a viable way of financing health care. This is in large part due to Singapore’s apparent success in using these accounts in combination with other financing mechanisms to provide high-quality care at comparatively low cost. In recent years, MSAs have been discussed by policymakers and interest groups in Canada and some European countries, although they have not been introduced in any of these nations (Hurley et al., Reference Hurley, Guindon, Rynard and Morgan2008; Thomson et al., Reference Thorpe2010).

One reason for this interest is that MSAs have been promoted by prominent think tanks. For example, the Adam Smith Institute in the United Kingdom (UK) has called for a rapid move away from the National Health Service – a universal, tax-funded health system – to a system funded through individual MSAs (Worstall, Reference Worstall2013; Goldsworthy, Reference Goldsworthy2014). Although the argument was based on questionable cross-country comparisons and was light on detail of how such a scheme would work, the recommendation should not be ignored as the Institute is influential with the government that came to power in the 2015 general election in the UK. In the United States of America (USA), a widely circulated book published by the Brookings Institution lauded the Singaporean health system for providing ‘affordable excellence’ (Haseltine, Reference Haseltine2013), although this interpretation was subsequently challenged (McKee and Busse, Reference McKee and Busse2013). There are current Republican proposals to repeal the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, colloquially known as Obamacare, and to expand the use of MSAs in the USA (Lueck, Reference Lueck2015; Park and Biniek, Reference Park and Biniek2015).

MSAs allow individuals and/or households to withdraw money from earmarked funds to pay for eligible health-care costs; employers often also contribute to these personalized accounts. Enrollees therefore pool risks over time, although they do not pool risks across the wider population. The accounts are usually accompanied by out-of-pocket payments and a high-deductible insurance plan that covers catastrophic costs. In the USA, this combination is sometimes called ‘consumer-directed health care’ (Buchmueller, Reference Buchmueller2008). MSA plans can differ in terms of cost sharing (i.e. user charges), contribution and spending rules.

The key aims of MSAs include: (1) encouraging personal responsibility for health and health care; (2) increasing provider choice for patients; (3) enhancing financial protection; (4) improving efficiency; and (5) controlling health-care costs. The extent to which they achieve these goals is widely debated (Gramm, Reference Gramm1994; Hsiao, Reference Hsiao1995; Massaro and Wong, Reference Massaro and Wong1995; Pauly and Goodman, Reference Pauly and Goodman1995; Thorpe, Reference Thomson, Võrk, Habicht, Rooväli, Evetovits and Habicht1995; Dixon, Reference Dixon2002; Davis, Reference Davis2004; Lee and Zapert, Reference Lee and Zapert2005; McConnell, Reference McConnell2005; Robinson, Reference Robinson2005; Bloche, Reference Bloche2006, Reference Bloche2007; Buntin et al., Reference Buntin, Damberg, Haviland, Kapur, Lurie, McDevitt and Marquis2006; Remler and Glied, Reference Remler and Glied2006; Baicker et al., Reference Baicker, Dow and Wolfson2007; Woolhandler and Himmelstein, Reference Woolhandler and Himmelstein2007; Haseltine, Reference Haseltine2013; McKee and Busse, Reference McKee and Busse2013; Park, Reference Park2015).

This article provides a critical assessment of MSAs as a financing option for health care. We briefly outline the key features of existing MSA schemes, and review the evidence on the association of MSAs with efficiency, equity and financial protection.

MSA designs

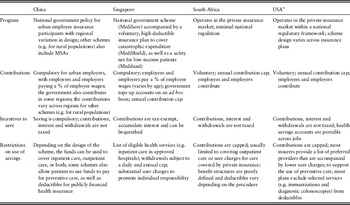

MSAs currently only play a significant role in the financing of health care in China, Singapore, South Africa and the USA (Table 1). In Singapore, Medisave is a compulsory MSA scheme launched in 1984 to limit government exposure to health-care costs. It is complemented by two other components: MediShield, a voluntary high-deductible, catastrophic insurance plan and the Medical Endowment Fund (Medifund), a safety net for poorer people. Medisave and Medishield are part of the Central Provident Fund, a government-managed savings scheme (Barr, Reference Barr2001; Hsiao, Reference Hsiao2001; Asher and Nandy, Reference Asher and Nandy2006; Asher et al., Reference Asher, Ramesh and Maresso2008). In recent years, other components aimed at high-income individuals, older people and long-term care recipients have been introduced.

Table 1 Key features of medical savings account (MSA) schemes

a This information relates to health savings accounts.

Source: adapted from Cylus and Thomson (Reference Cylus and Thomson2012).

China introduced compulsory MSAs for all urban employees in 1998 to try to increase the proportion of insured individuals, protect patients from impoverishment due to medical expenses, and enhance price competition in primary care to contain costs. The accounts are accompanied by a publicly financed risk-pooling fund that covers catastrophic medical expenses. In 2003, the government also introduced a government-managed, voluntary financing scheme for the rural Chinese population, and many counties now use a combination of MSAs and high-deductible catastrophic insurance to cover this population (Yip and Hsiao, Reference Yip and Hsiao1997; Lei and Lin, Reference Lei and Lin2009; Yip and Hsiao, Reference Yip and Hsiao2009). The administration of the rural scheme has been devolved to local governments.

In South Africa, voluntary MSAs were introduced in 1994 to limit financial risk for private insurers. Initially, insurers were allowed to design their own MSA plans. During the 2000s, regulation of MSAs was phased in to deter aggressive selection of healthy individuals, to minimize the exploitation of tax loopholes, and to reduce the threat to social solidarity (McLeod and McIntyre, Reference McLeod and McIntyre2008).

MSAs were introduced in the USA in 2003 and are generally known as health savings accounts (HSAs). HSAs are voluntary, employer-sponsored schemes that are often managed by private insurers or other financial institutions; they are also available for individual purchase. The aim of HSAs is to increase insurance coverage rates and to curb health expenditure growth. Between 2006 and 2010, the number of registered HSAs grew from 1.3 million to 8.4 million, corresponding to an increase from USD 873.4 million to USD 12.4 billion in HSA assets (Fronstin, Reference Fronstin2012). Individuals still have to pay for some health-care costs out-of-pocket, and there is no government-underwritten catastrophic coverage (Glied, Reference Glied2008). Health reimbursement accounts (HRAs) – another common type of consumer-directed health plan (CDHP) – were available before 2003. HRAs operate similarly to HSAs, but the former are not portable between employers and only employers can contribute to them. There is also no limit on how much employers can contribute each year to HRAs, and it is not required that the accounts be coupled with high-deductible insurance plans (Buchmueller, Reference Buchmueller2008).

How well do MSAs meet their stated goals?

This section reviews evidence on the effects of MSAs on efficiency, equity and financial protection. These dimensions have been the focus of empirical studies of MSAs to date. Two authors (O.J.W. and W.Y.) independently searched Cochrane, EconLit, MEDLINE, Scopus and ISI Web of Science databases for peer-reviewed, empirical studies written in Chinese or English that looked at the association between MSAs and one or more of these three outcomes (i.e. efficiency, equity and financial protection).

We searched titles and abstracts using the terms ‘consumer-directed health care’, ‘health savings account’, ‘medical savings account’ and the plural forms of these terms; we considered all literature published up until 24 September 2015, when the search was conducted. After removing duplicates and articles with no abstracts, both authors separately screened the abstracts/titles and reviewed the full texts of potentially relevant articles. Disagreements over article inclusions were resolved through discussions between the two authors.

We also hand searched the reference lists of selected articles and one author (W.Y.) searched the China National Knowledge Infrastructure database using the term ‘medical savings account’ (in Chinese). We identified other relevant peer-reviewed and gray literature from Google searches. Most of the available empirical evidence comes from the USA; we included studies of both HSAs and HRAs.

Efficiency

It is suggested that MSAs, like user charges, can enhance efficiency and, potentially, control health-care costs by reducing the use of low-value treatments. Analyses of selected employer-sponsored plans in the USA, however, have suggested that HSAs discourage the use of both low- and high-value treatments (Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Greene and Hibbard2008; Parente et al., Reference Parente, Feldman and Chen2008; Hardie et al., Reference Hardie, Lo Sasso, Shah and Levin2010; Buntin et al., Reference Buntin, Haviland, McDevitt and Sood2011; Charlton et al., Reference Charlton, Levy, High, Schneider and Brooks2011). One study (Greene et al., Reference Greene, Hibbard, Dixon and Tusler2008) observed that enrollment in CDHPs did not greatly influence the use of generic medicines. Instead, enrollees in high-deductible CDHPs were two to three times more likely to discontinue pharmacologic treatment in two of five drug classes – anti-hypertensive and lipid-lowering medicines – than were enrollees with other types of coverage (Greene et al., Reference Greene, Hibbard, Dixon and Tusler2008). Another study showed that enrollment in CDHPs with HSAs was associated with reduced adherence to medicines among patients with four out of five selected chronic conditions (Fronstin et al., Reference Fronstin, Sepúlveda and Roebuck2013a).

Researchers have generally concluded that individuals who switch from traditional insurance plans to CDHPs tend to spend less on health care during the first one to three years after the switch compared to those who stay in traditional plans (Parente et al., Reference Parente, Feldman and Christianson2004a; Lo Sasso et al., Reference Lo Sasso, Rice, Gabel and Whitmore2010; Buntin et al., Reference Buntin, Haviland, McDevitt and Sood2011; Charlton et al., Reference Charlton, Levy, High, Schneider and Brooks2011). This effect appears to be more pronounced for those who enroll in CDHPs with higher deductibles (Haviland et al., Reference Haviland, Sood, McDevitt and Marquis2011). For example, an analysis of spending patterns over three years among 76,310 employees at small and mid sized firms – 22,587 of whom enrolled in HSAs during that time – found that HSA enrollees spent, on average, between 5% and 7% less per year in total than non-HSA enrollees, controlling for confounders; much of the observed reduction in overall spending occurred during the first year of enrollment (Lo Sasso et al., Reference Lo Sasso, Rice, Gabel and Whitmore2010). Another study showed that, on average, CDHP enrollees spent less overall over three years of follow-up than did enrollees in a preferred provider organisation (PPO), controlling for enrollee characteristics; CDHP enrollees, however, spent more than enrollees in a health maintenance organisation (HMO). The authors noted that these results were ‘not consistent across different types of medical expenditures, and there [were] differences by employer vs employee payment’ (Parente et al., Reference Parente, Feldman and Christianson2004a).

Yet, if MSAs deter the use of effective, high-value treatment where the benefits might not be immediate or obvious to patients (e.g. preventive care like cancer screening), this could raise health expenditure over time. One study observed that enrollees in a CDHP had both fewer prescriptions filled (0.26 per enrollee per year) and fewer office visits to physicians (0.85 per enrollee per year) after four years than did enrollees in a PPO, but the former group also had slightly more emergency department visits after four years (0.018 per enrollee per year) (Fronstin et al., Reference Fronstin, Sepúlveda and Roebuck2013b). Another study similarly found that enrollees in a CDHP had, on average, fewer physician visits and fewer prescriptions filled than did enrollees in a PPO or a HMO during the study period; CDHP enrollees also routinely paid less out-of-pocket than did enrollees in the PPO (Parente et al., Reference Parente, Feldman and Christianson2004a). However the CDHP cohort had a larger growth in hospital costs and admission rates between 2000 and 2002 than did enrollees in either the PPO or the HMO, with a sharp rise in hospital expenditure in the third year of follow-up among CDHP enrollees. The authors suggested that enrollment in a CDHP might have made the patients more price conscious and led them to forego care until they fell ill and needed to be hospitalized, but acknowledged it was not possible to attribute causality based on the study data (Parente et al., Reference Parente, Feldman and Christianson2004a).

Such findings are in line with evidence from the RAND Health Insurance Experiment, which suggested that most patients are unable to distinguish consistently between high- and low-value treatments (Newhouse, Reference Newhouse1993). Not all US studies, however, have found that enrollment in CDHPs reduces the use of preventive care, probably because such care is often exempt from out-of-pocket payments (Rowe et al., Reference Rowe, Brown-Stevenson, Downey and Newhouse2008; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Bargman, Pederson, Wilson, Garrett, Plocher and Ailiff2008; Cress and Zimmer, Reference Cress and Zimmer2011). Others have also found that educating HSA enrollees about the possible savings from choosing cheaper generic drugs instead of more expensive brand-name drugs is associated with greater use of the former (Sedjo and Cox, Reference Sedjo and Cox2009). Beyond such measures, it is unclear whether MSA plans can be designed in ways that consistently discourage the use of low-value care and not high-value care.

Another issue is that once individuals with an accompanying insurance plan have met the deductible, additional health care is usually covered at no extra charge by the insurer. Thus, even if MSAs discourage the use of low-cost, low-value health care, they are less likely to influence the use of costly health care over which these enrollees have limited control (Monheit, Reference Monheit2003; Stanton and Rutherford, Reference Stanton and Rutherford2006).

MSAs are also unlikely to have a significant effect on health-care costs where they are voluntary, because low-income individuals and families, who account for a disproportionate share of health spending, have been shown to be less likely to enroll and/or contribute to their accounts (Parente et al., Reference Parente, Feldman and Christianson2004a, Reference Parente, Feldman and Christianson2004b; Minicozzi, Reference Minicozzi2006; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Lo Sasso and Nandam2013; Helmchen et al., Reference Helmchen, Brown, Lurie and Lo Sasso2015). Several studies have suggested that MSAs and CDHPs tend to attract healthier, lower-risk, younger, higher-income and/or better-educated patients (Fowles et al., Reference Fowles, Kind, Braun and Bertko2004; Lo Sasso et al., Reference Lo Sasso, Shah and Frogner2004; Tollen et al., Reference Tollen, Ross and Poor2004; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Hibbard, Murray, Teutsch and Berger2006; Lo Sasso et al., Reference Lo Sasso, Rice, Gabel and Whitmore2010; Charlton et al., Reference Charlton, Levy, High, Schneider and Brooks2011), although not all analyses show that MSA enrollees are, on average, younger or healthier than non-MSA enrollees (Parente et al., Reference Parente, Feldman and Christianson2004b; Minicozzi, Reference Minicozzi2006). The demographics and health status of MSA enrollees are likely to depend in part on plan design and the incentives offered to enrollees by individual MSA providers.

Proponents of MSAs claim that they enhance consumer choice and encourage price competition if rational and informed consumers actively search for the cheapest care, assuming constant quality (i.e. active purchasing). In one study, enrollees in low-deductible CDHPs reported being more likely than enrollees in other plans to start using health-care information when seeking care, such as looking at drug costs from the previous year and comparing quality information from different hospitals (Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Greene and Hibbard2008). However, an interview-based study showed that only around half of the 458 adult interviewees – all of whom had recently enrolled in a CDHP with a deductible – were aware they had a deductible, while fewer than 7% knew which medical services were subject to or exempt from the deductible (Reed et al., Reference Reed, Graetz, Wang, Fung, Newhouse and Hsu2009). Low awareness of such information is likely to impede MSA enrollees from engaging in active purchasing. One analysis also suggested that a large proportion of primary-care clinicians were not prepared, at the time of the study, to provide information to patients enrolled in HSAs about the costs of various medical services, including radiologic tests (54% of sampled clinicians reported being ‘ready’ or ‘very ready’; 95% CI: 50–59%), specialist visits (38%; 95% CI: 33–42%) and hospitalizations (33%; 95% CI: 29–37%) (Mallya et al., Reference Mallya, Pollack and Polsky2008); more than two-thirds of the 528 respondents, however, felt ready to give advice to patients about the costs of laboratory tests, office visits and medications.

Several articles have highlighted how difficult it is for patients to obtain price and quality information about health-care services in the USA (Reinhardt, Reference Reed, Benedetti, Brand, Newhouse and Hsu2006; Muhlestein et al., Reference Muhlestein, Wilks and Richter2013), while interviews with health policy experts in South Africa found little price competition after the introduction of MSAs (Jost, Reference Jost2005). In South Africa, MSAs have instead shifted the focus of private insurers away from the active purchasing of more efficient, better-quality health care and towards risk selection and shifting costs onto policy holders to keep premiums low (McLeod and McIntyre, Reference McLeod and McIntyre2008). In China, where a large proportion of health care is financed through out-of-pocket payments, it is common for doctors to ask patients during consultations whether they have funds available in their MSAs. This may lead some doctors to over-prescribe medicines and diagnostic tests to those with large surpluses in their accounts (Xue and Zhao, Reference Xue and Zhao2007; Sheng and Hou, Reference Sheng and Hou2011). Overall, more research is needed to determine whether it is feasible for institutions to collect and disseminate easy-to-understand price and quality data to patients in countries where MSAs are available. It would also be important to see whether patients can use such information effectively when purchasing health care.

Equity and financial protection

MSAs allow enrollees to spread the financial risk of ill health over time. They do not, however, ensure that people will have enough savings to pay for large, unexpected health-care bills, nor do they foster social solidarity (Jost, Reference Jost2007). In 2011, Medisave withdrawals and Medishield claims only accounted for about 5.5% and 2.1% of national health expenditure in Singapore, respectively (Singapore Ministry of Health, 2013), with most health care paid for out-of-pocket. One study suggested that HSA enrollees in the USA who paid for their own accounts – with no employer contributions – were significantly more likely to report financial burdens than enrollees with only employer contributions (17.3% vs 11.9%, p<0.05) (Reed et al., Reference Reinhardt2012).

In Singapore and China, the use of earned income to finance MSAs discriminates against retired, unemployed, disabled and chronically ill people (Jost, Reference Jost2007). A US study found that employees with chronic illnesses were more likely than other employees to deplete their HSA savings and to spend more on their deductibles (Parente et al., Reference Parente, Christianson and Feldman2007). Another analysis observed that enrollment in CDHPs was associated with a similar reduction in beneficial care among both vulnerable and non-vulnerable patient groups (Haviland et al., Reference Haviland, Sood, McDevitt and Marquis2011). The authors posited that this might impact the health of low-income and chronically ill patients more than the health of non-vulnerable groups (Haviland et al., Reference Haviland, Sood, McDevitt and Marquis2011).

Yip and Hsiao (Reference Yip and Hsiao2009) modeled the financial protection offered by first-dollar coverage plans and MSAs in rural Chinese regions based on household data. They determined that first-dollar plans were more likely to limit impoverishment due to medical expenses than MSAs coupled with high-deductible catastrophic coverage: the empirical model suggested that first-dollar plans would lower the poverty headcount by 6.1–6.8%, whereas joint MSAs/catastrophic insurance would lower the headcount by 3.5–3.9%. These calculations were based on a poverty line of USD 1.08 per person per day. The authors attributed this finding to the fact that MSA funds could not be spent on outpatient care, which was the main source of impoverishment for chronically ill people in the study regions. Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Zhao, Cai, Yamada and Yamada2002) showed that the introduction of MSAs as part of employee health insurance in Zhenjiang, China, increased the use of outpatient health care among lower socioeconomic groups, although Yi et al. (Reference Yi, Maynard, Liu, Xiong and Lin2005) concluded that the Zhenjiang pilot model of health care financing was regressive. Data from the first year of the Jiujiang and Zhenjiang pilot studies suggested the reform shifted the financial burden from the healthy to the sick (Yip and Hsiao, Reference Yip and Hsiao1997). Those patients who exhausted the funds in their MSAs had to pay a deductible corresponding to 5% of their wages before insurance would begin to cover additional costs (Yip and Hsiao, Reference Yip and Hsiao1997). Pei (Reference Pei2008), Liu and Chen (Reference Liu and Chen2013) and Xia (Reference Xia2014) have all found that, because of the lack of risk pooling across individuals, Chinese patients with substantial health needs tend to deplete their MSAs, while young and healthy patients tend to keep large, unused surpluses in their accounts.

Tax exemptions and subsidies for MSAs in the USA and Singapore often benefit wealthier people disproportionately, especially when provided at the marginal rate of taxation so that individuals in higher tax brackets receive greater tax relief. Even if tax exemptions were provided at a standard rate, they would not benefit those who do not pay taxes, including unemployed people, non-working dependants and individuals with earnings below the tax threshold (Glied and Remler, Reference Glied and Remler2005; Hoffman and Tolbert, Reference Hoffman and Tolbert2006; Minicozzi, Reference Minicozzi2006).

Furthermore, HSAs attract a triple tax benefit in the USA: the contributions are tax-deductible, the earned interest is tax-free and the withdrawals to pay for approved medical costs are tax-free. HSAs are marketed as effective savings vehicles to help people pay for health-care costs at older ages, as long as the savings are not used until retirement (Fronstin, Reference Fronstin2014); after age 65, HSA funds can be used to pay for non-medical expenses, without penalty, although ordinary taxes still apply. Such savings, however, would be more likely to benefit those individuals who are wealthy or healthy enough not to need the savings to cover out-of-pocket costs, including insurance premiums, before retirement. For example, one study estimated that a 55-year-old couple setting up an HSA in 2008 would need to accumulate between USD 511,000 and USD 1 million by the age of 65 to have a 90% chance of having enough savings to cover these expenses in retirement, assuming premiums and other out-of-pocket costs do not rise faster than adjustments for inflation (Fronstin, Reference Fronstin2014).

Discussion

Country experiences with MSAs indicate the schemes have generally been inefficient and inequitable and have not provided adequate financial protection. The impact of the schemes on long-term health-care costs is unclear. The lack of interpersonal risk pooling in MSAs is a key limitation.

In China, the mismatch between MSA funds and health-care demand led to a total MSA surplus of RMB 323 billion in 2014 (USD 50.5 billion based on the average exchange rate for that year), which was equal to the combined value of all publicly financed health insurance premiums (Xinhua News, 2015). Some Chinese cities are experimenting with ways of making better use of MSA funds. In 2009, Zhenjiang City separated MSAs into two accounts. The main account can be used to pay for most types of care, including outpatient, inpatient, preventive and long-term care; previously, it could only be used for outpatient care. All funds above RMB 3000 (USD 469) are saved in the secondary account, which can also be used to pay for the health care of family members (Xinhua News, 2009). Since 2009, the Zhenjiang model has been adopted by a growing number of cities in China. In Chengdu City, for example, MSA participants can now use funds to pay for private health insurance premiums (Sichuan News, 2015). Other cities, including Dalian, Shanghai, Shenyang and Zhongshan, are piloting similar initiatives (Xinhua News, 2015).

Yet, MSAs continue to be suggested as appropriate financing options in other countries, often by policymakers in finance ministries (Thomson et al., Reference Thorpe2010). This may be because savings are so commonly used to finance pensions, and people seem to extrapolate from pensions to health. However, unlike the more predictable need for income replacement during retirement, ill health is characterized by a high degree of uncertainty, which means that individual savings alone cannot provide adequate financial protection for everyone faced with health-care expenses. It is also possible that the lobbying activities of stakeholders help bring MSAs to the forefront of political discussions. Banks and other companies offering financial services may have strong motives to encourage MSAs given the fees involved, while other individuals and groups may be ideologically driven to endorse individual accounts instead of options with mandatory risk pooling across individuals.

Some of the weaknesses of MSAs could be addressed by coupling MSAs with supply-side measures, like rewarding low-cost providers to correct price competition failures. If MSAs are to be adopted, it will also be important to foster an economic and regulatory environment that is conducive to market-oriented plans. Prerequisites for the viability and sustainability of MSAs include a high income per capita, a national culture of saving and personal responsibility for health, and a well-functioning and transparent regulatory environment, both in the health sector and in the financial services sector (Nichols et al., Reference Nichols, Prescott and Phua1997; Chia and Tsui, Reference Chia and Tsui2005).

Finally, this review has shown how MSAs are often coupled with high-deductible plans, both of which can take a variety of forms. It is not possible, with the evidence available, to draw firm conclusions about whether MSAs can ameliorate the problems associated with high-deductible plans. This is an area where more research is needed, although findings may be difficult to interpret given differences in context, such as the presence of other safety nets, as in Singapore. It is likely, however, that systems with greater complexity, where patients draw on multiple plans, will leave more people to fall through the net. This is supported by findings cited earlier that indicate a social gradient in MSA take up and that show how few people fully understand the deductibles associated with plans in which they are already enrolled.

Despite the recent fervor over MSAs, the case that so-called consumer-directed solutions achieve their objectives remains unproven.

Acknowledgments

No sources of funding were used to prepare this manuscript. The authors have no conflicts of interest that are relevant to the content of this article.