The Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania (UDMR) qualifies as a small party in the Romanian multiparty system. It wins on average 6% of seats in the Romanian bicameral parliament, is the preferred coalition partner for the larger liberal and social democratic mainstream parties and was more than once a ‘king-maker’ during coalition bargaining. Regardless of its privileged bargaining position for government membership, the UDMR did not always target government offices. At times, having policy influence was sufficient for it to grant support to minority cabinets. Minority cabinets are a common phenomenon in Romania. They represent half of all democratic Romanian governments (15 out of 30) and ethnic minority groups had a significant role in their recurrence. Some ethnic minority groups never even considered an executive role. This contrasts with the temporary nature ascribed by similar small mainstream parties to their role as support partners. What is the rationale behind the different choice of coalition participation strategies, and is there sufficient evidence that we should consider these differences when anticipating minority government formation and survival?

In the field of coalition studies, it is now generally accepted that minority governments are rational outcomes under certain conditions (Strøm Reference Strøm1984, Reference Strøm1990). The commonality of this type of cabinet has been regularly noted and analysed (Bassi Reference Bassi2017; Field Reference Field2016; Green-Pedersen Reference Green-Pedersen2001). These studies investigated why non-governmental parties would still offer legislative support without access to offices and cabinet authority. Thus far, the general conclusion is that policy influence is at the core of their motivations (Bassi Reference Bassi2017; Hix and Noury Reference Hix and Noury2016). However, under strongly formalized agreements, non-cabinet parties may also get junior positions in the administration in exchange for their support (Bale and Bergman Reference Bale and Bergman2006b). Through an in-depth within-case study of Romanian minority governments (1990–2018) and their support partners, we aim to contribute to previous research by systematically investigating the different types of pay-offs that support parties try to gain under minority governments.

Our main argument is that support party pay-offs under minority governments depend on the party type of the support partner. Parties are known to be either policy-, office- or vote-seeking (Müller and Strøm Reference Müller and Strøm1999). In contrast to mainstream parties, ethno-regional parties (Field Reference Field2016; Heller Reference Heller2002; Meguid Reference Meguid2008), as a specific type of the broader category of niche parties (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2006; Meguid Reference Meguid2005), are known to concentrate on group-specific policy benefits. The results of our empirical analysis support this argument and challenge the widespread understanding that all support parties are mostly policy-seeking (Strøm Reference Strøm1984, Reference Strøm1990).

This article continues as follows. The theoretical framework covers the advances in the study of minority cabinet formation and the formalization of legislative support through written support agreements. Based on this, we develop our theoretical expectations of the variance in parties’ pay-off demands in exchange for giving support to minority cabinets. In the second part, we introduce the mixed-methods research design and explain the utility of the Romanian case. Afterwards, we compare the content of support agreements based on a newly compiled data set on 10 support agreements. Moreover, we compare two types of support party relationships under two minority cabinets and trace the stealthier negotiations for support through elite interviews. We argue that the combination of this with the original, previously unavailable data allows us precious insights into party competition and coalition bargaining under minority governments. We conclude with an overall discussion of the empirical results.

The rationality of minority cabinets

Due to the special relationship of confidence between the legislature and the government in parliamentary democracies, a cabinet can only survive if it is – directly or indirectly – supported by a majority of deputies (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1999). This is the reason why minority governments have conventionally been seen as phenomena of political crises and instability (Taylor and Herman Reference Taylor and Herman1971). The traditional approaches on government formation focused on office-seeking political actors and assumed that the formation of minority governments is irrational (Gamson Reference Gamson1961; Riker Reference Riker1962). This approach was, however, criticized as policy-blind by later generations of researchers (Axelrod Reference Axelrod1970; de Swaan Reference de Swaan1973). However, Ian Budge and Hans Keman (Reference Budge and Keman1993: 47) argue that the position of the government is weaker where it commands only a minority of seats, ‘but it is not by any means untenable’.

Since the seminal contributions of Kaare Strøm (Reference Strøm1984, Reference Strøm1990), it has become increasingly accepted that the formation of minority governments can be a rational decision for political actors. He argues that forming minority cabinets can be a rational choice if opposition parties can exert influence on policymaking from the opposition – for example, through strong parliamentary committees. Catherine Moury and Jorge Fernandes (Reference Moury and Fernandes2018) show that opposition parties are indeed more successful in implementing their policy promises under minority than under majority cabinets. The institutionalist approach concentrated on the impact of investiture vote procedures (Bergman Reference Bergman1993) or strong government agenda-setting powers (Heller Reference Heller2001) to explain the formation of minority cabinets.

Importantly, there is significant variation in the way minority governments work. Observing Danish cabinet politics, Erik Damgaard (Reference Damgaard1969) distinguishes between minority cabinets with a ‘more or less permanent’ partner in parliament and cabinets which cannot rely on permanent partners but form ad hoc coalitions. This has important implications for government stability (Warwick Reference Warwick1994) and policymaking (Christiansen and Pedersen Reference Christiansen and Pedersen2014). Simon Otjes and Tom Louwerse (Reference Otjes and Louwerse2014) argue that strongly formalized legislative coalitions can lead to less cooperation with other non-cabinet parties than under majority governments. Further, Philip Manow (Reference Manow2008) finds that policy outcomes (e.g. environmental protection) can be explained better by investigating the role of support parties, and Bonnie Field (Reference Field2016) shows that minority cabinets supported by regional parties are a successful arrangement in the Spanish multilevel system.

Considering the importance of understanding how minority cabinets work in practice, it is surprising to see how little research has covered the support agreements or support party benefits (see, for an exception, Bale and Bergman Reference Bale and Bergman2006a, Reference Bale and Bergman2006b) they rely on. In parallel, scholars have increasingly acknowledged the importance of the text of coalition agreements for the life of cabinets (e.g. Bäck et al. Reference Bäck, Müller and Nyblade2017; Klüver and Bäck Reference Klüver and BäckForthcoming; Moury Reference Moury2013; Müller et al. Reference Müller, Bergman, Strøm, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008). In this study, we aim to analyse the content of explicit support agreements using similar tools and explain the variance among support parties’ demands.

The role of support party agreements and support party benefits

The concepts of support agreements and support parties are intertwined. Studies that employ them assume an intrinsic link between them. And yet, so far, there is very little research on the variation among the agreements. This is partly due to the fact that the concept of support agreements is hard to define (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1999) and fairly disputed among scholars (see Thesen Reference Thesen2016). G. Bingham Powell (Reference Powell1994) states that support agreements can vary significantly between ‘informal understandings’ and extensive written agreements including policy deals. The existence of a written support agreement is used as an indicator of a ‘narrow definition’ of a support party's relationship (Bäck and Bergman Reference Bäck, Bergman and Pierre2015: 213; Warwick Reference Warwick1994: 31–32). A ‘broad definition’ includes implicit agreements such as those based on secret cooperation or agreements without direct pay-offs for the support party and can be identified by announcements or party behaviour (for example, by voting in line with the government or by abstaining) that directly helps a minority cabinet to survive (see also Bergman Reference Bergman1995: 29).

Strøm (Reference Strøm1990) uses the narrow definition for his influential study of minority governments. His definition of formal minority governments is based on two factors: ‘it [the agreement] was negotiated prior to the formation of the government, and takes the form of an explicit, comprehensive, and more than short-term commitment to the policies as well as the survival of the government’ (Strøm Reference Strøm1990: 62). If there is an explicit written support agreement that is available to the public, Tim Bale and Torbjörn Bergman (Reference Bale and Bergman2006a) argue that this form of ‘contract parliamentarianism’ commits the parties for more than a short period or one policy deal.

But what do support parties stand to gain from their status? The role of support parties may appear unrewarding. Parties back the cabinet in all major votes and ensure its survival, but do not gain any important or influential ministerial positions. Bale and Bergman (Reference Bale and Bergman2006b) reduce green parties who support minority cabinets in Sweden and New Zealand to the status of ‘captives’. However, a study by Hanne Narud and Henry Valen (Reference Narud, Valen, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008) demonstrates that members of a coalition government often see a decline in electoral support in the next general election, and Heike Klüver and Jae-Jae Spoon (Reference Klüver and Spoon2017) highlight that junior coalition partners especially must expect severe electoral losses. Taking this into account, the role of a support party becomes more appealing. Gunnar Thesen (Reference Thesen2016) reveals that, in contrast to government members, being a support party does not affect Danish parties’ electoral success negatively, and David Fortunato and James Adams (Reference Fortunato and Adams2015) argue that remaining outside government coalitions, especially for niche parties, translates into maintaining their ideological image and keeping their reputation. Hence, parties that are not first and foremost office-seeking have strong incentives to become support parties.

Niche parties form a broad category and are expected to behave differently from mainstream parties when it comes to party competition and government formation (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2006; Meguid Reference Meguid2008; Wagner Reference Wagner2012). It is claimed that they are less interested in public office and more keen on influencing policies in their specific area of interest. In light of new evidence, we can further refine our understanding of this composite category. Ethno-regional parties are a special type of niche parties (Meguid Reference Meguid2008). Lieven de Winter (Reference de Winter, de Winter and Tursan1998) claims that the electorate of ethno-regional parties is substantially divided on the socioeconomic policy dimension, explaining why these parties tend not to compete on these issues. Field (Reference Field2016) argues that the different goals of Spanish regional parties allow minority cabinets to work at the national level. William Heller (Reference Heller2002) explains that regional parties are willing to support minority governments in exchange for ‘transfers of policy-making authority’ for their groups (or regions). This behaviour by ethno-regional parties is linked to the expectations of their more heterogeneous electorate (de Winter Reference de Winter, de Winter and Tursan1998).

Along similar lines, we reason that regional parties (Field Reference Field2016), as well as ethnic minority parties (Bird Reference Bird2014), are especially successful in defending their groups’ interests under national minority governments – in the form of, for example, more group authority, more public spending that benefits their group, or other policy pay-offs for their group. Similar qualifiers apply to both categories despite potential differences between them. For the scope of this study, we have therefore used the concepts ethno-regional, ethnic and regional interchangeably.

Support relationships between minority governments and ethno-regional parties are thus beneficial for both partners: the ethno-regional support party and the minority cabinet. Therefore, and in line with Strøm's (Reference Strøm1984) assumption on the rationality of staying outside government, it might not be feasible for ethno-regional parties to enter government in the first place as this could constrain the choice-set available to them, leaving the pursuit of policy accommodation as the only viable option. While the ethno-regional party is satisfied with securing authority and financial support for its specific group, it is less involved in national legislations and has little interest in office positions.

However, minority governments do not only form support agreements with ethno-regional parties, but also have support agreements with mainstream parties. Under these circumstances, they form a legislative coalition with a non-cabinet party that directly competes with the cabinet parties on the same policy dimensions, and over future voters and offices. Based on the fact that they compete for the same voters on the same dimension, we assume that mainstream parties behave differently from ethno-regional parties in the role of support parties. Firstly, we expect these parties to concentrate more on ‘classical’ policy dimensions – such as economic or foreign policies – since most voters at the national level care about these issues and these are the fundamental dimensions on which mainstream parties win votes. Secondly, we know that support parties also try to achieve junior positions in the administration or parliament in exchange for their support of minority cabinets (Bale and Bergman Reference Bale and Bergman2006a). In line with previous literature on party behaviour and party goals (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2006; Müller and Strøm Reference Müller and Strøm1999), we assume this to be especially true for mainstream support parties. Based on these previous findings, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis:

Ethno-regional parties are mostly interested in securing group-focused policies in exchange for their support of the minority cabinet, while mainstream support parties are more likely to compete along classical policy dimensions and claim office pay-offs.

Data and methodology

This study is a mixed-methods research that combines text analysis of the content of 10 explicit support agreements with two case studies of two specific minority cabinets each signing support agreements with mainstream and ethnic minority groups at the same time. For the purpose of this study, we follow Bale and Bergman (Reference Bale and Bergman2006a) and define an explicit support agreement as the long-term cooperation between the cabinet and the support party based on a written agreement with pay-offs for the support partner in exchange for government support. Moreover, the existence and the major bargaining results of the agreement must have been made public (though the whole agreement need not have been published). In contrast, the concept of implicit support agreements is looser and includes cooperation between the cabinet and a support party which is based on a non-written agreement. This type of agreement can be identified either by a public announcement by the parties or by party behaviour (for example voting in favour of a motion of confidence). The choice to concentrate on explicit support agreements not only allows us to analyse in a comparative way what policy pay-offs support parties aim to gain (through the text of support agreements) but also makes it possible to compare directly the efforts and pay-offs of mainstream parties with those of ethno-regional parties for two example governments. For more information on the ‘behind closed doors’ bargaining for minority cabinet formation and maintenance, we rely on seven semi-structured elite interviews with the prime minister of a minority cabinet and the top negotiators for the analysed legislative agreements, members of the cabinets or high-ranking party leaders. Public statements made by other cabinet members relevant to this debate are also considered.

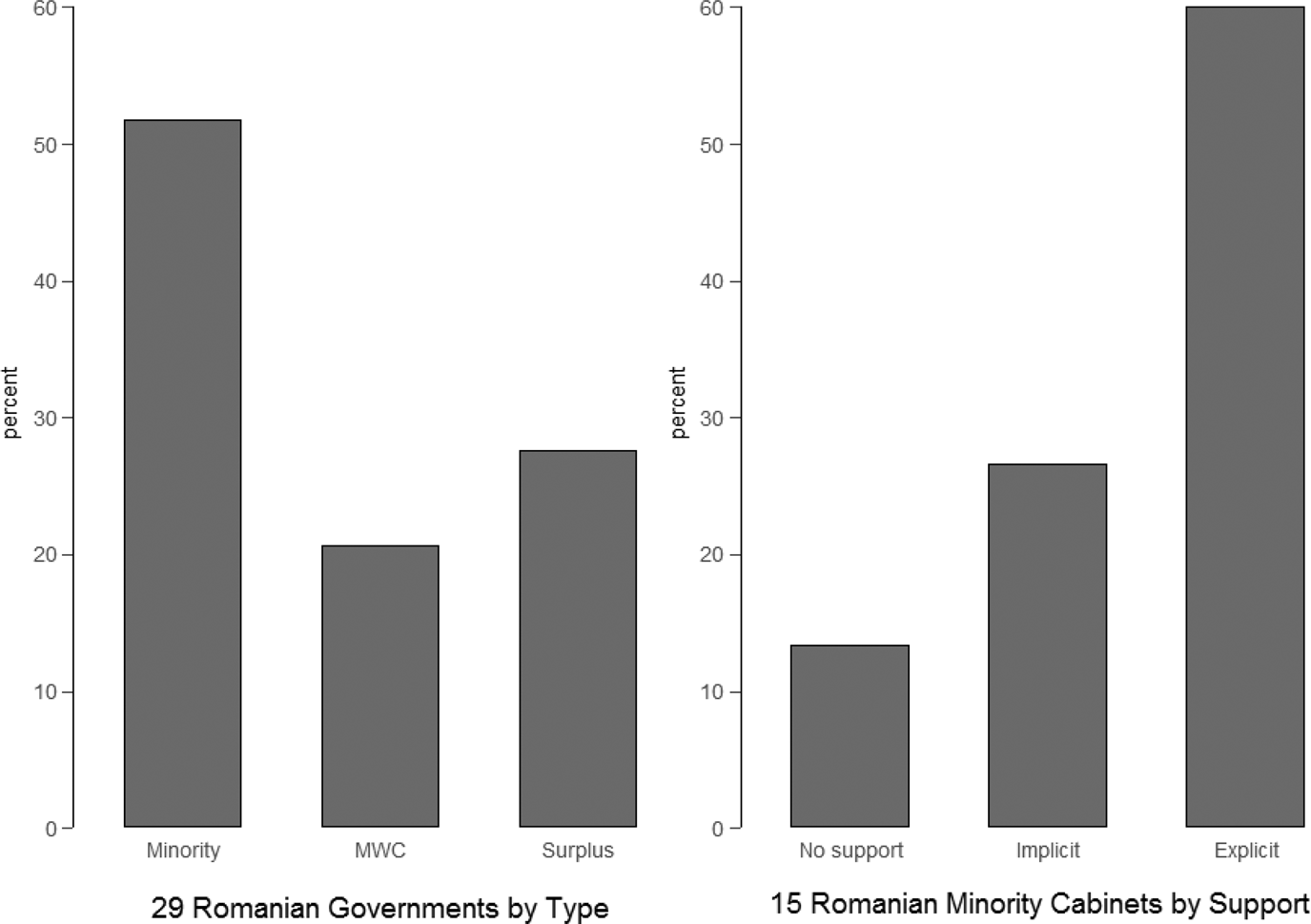

Fifteen of 29 Romanian political cabinets have formed as minority governments (see Figure 1).Footnote 1 This is more than half of the total number of political cabinets formed in Romania, after the first free elections of 1990 and up to 2018. Six other governments have been minimum winning (20%) and eight have been oversized or surplus coalitions (26.6%). Compared with the European average, Romania ranks in the top tier in the distribution of minority cabinets (Bassi Reference Bassi2017). However, while there has been ample research on minority cabinets in Sweden (e.g. Bäck and Bergman Reference Bäck, Bergman and Pierre2015), Denmark (e.g. Christiansen and Pedersen Reference Christiansen and Pedersen2014; Green-Pedersen Reference Green-Pedersen2001), Norway (e.g. Strøm Reference Strøm1990), Spain (Field Reference Field2016) and New Zealand (Bale and Dann Reference Bale and Dann2002), Romania has gained very little scholarly attention (see for an exception Chiva Reference Chiva, Rasch, Martin and Cheibub2015).

Figure 1. Romanian Governments by Type

This is puzzling, since the Romanian case of a post-communist democracy provides a rich and in-depth understanding of the phenomenon of minority governance. As the number of minority governments in democratic regimes has risen over the last century, this endeavour becomes increasingly relevant. The case of Romania offers not only a high number of minority cabinets but also a rather high number of explicit and written support agreements (see Figure 1).

In the following, we analyse 10 explicit support arrangements under nine minority governments. In this count, the same agreement was used by two different cabinets, and two cabinets had negotiated two explicit agreements with two different parliamentary groups. The other six minority cabinets functioned on implicit agreements or did not have agreements at all. The variance we observe in the type of support parties under minority cabinets makes Romania a suitable example for studying support party behaviour.

Moreover, studying Romania gives us the chance to investigate the actual influence of ethnic minority representatives and to contribute to the larger call for awareness of the vital importance of ethnic minority rights in Central and Eastern Europe (Chiva Reference Chiva2006). While scholars previously claimed that they underperform in representing their ethnic groups (Cârstocea Reference Cârstocea2013; Protsyk and Matichescu Reference Protsyk and Matichescu2010), our analysis charts the explicit actions of ethnic minority representatives on behalf of their groups, based on the assumption that a large part of their bargaining strategy with the minority cabinet is to ensure benefits and policy pay-offs for their electorate in exchange for legislative support (e.g. Bird Reference Bird2014). Our study empirically tests these claims.

As stated above, for the purpose of this study we concentrate on explicit or written agreements. We break down the specificities of the agreement according to length, policy content, office distribution and functioning mechanisms. A residual category entitled ‘ceremonial text’ amasses text used for introductory remarks related to the general context in which the contract was signed and miscellanea. We differentiated between the percentages of words dedicated to each category. This analysis breakdown converges with previous research projects related to coalition agreements (Bergman and Müller Reference Bergman and MüllerForthcoming; Müller and Strøm Reference Müller and Strøm2003). The authors performed the coding manually and relied on the native Romanian-language skills of one of them. The limited size of the texts instructed the preference for human coding, which is generally considered superior for the validity of the measurement (see e.g. Klüver Reference Klüver2009). We use ‘quasi-sentences’ as the unit of analysis (Klingemann et al. Reference Klingemann2006).

The total policy content was disentangled into structural, economic, social, foreign affairs and group-specific policies. We based our categories on the Manifesto Project (MARPOR) (Volkens et al. Reference Volkens, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel and Weßels2018). The reduced size of the texts, the scope of our research and case-specific considerations permitted us to limit the seven policy domains of the MARPOR to five. Based on the case-specific qualities of a post-communist state-building process, we decided to merge the ‘democracy’ and ‘party system’ MARPOR domains in a category titled ‘structural policies’. The ‘structural’ category measures the percentage of words addressing the intertwined issues related to general national administration (democratization, constitutional and electoral reform, party system). The ‘economic’ variable addresses the percentage of words related to budget allocation, fiscal and monetary issues and taxes. It also includes policies targeting specific economic groups such as farmers. The ‘social’ dimension measures the percentage of words addressing issues such as health and education expansion, civil rights and values and merges the MARPOR ‘welfare and quality of life’ and ‘fabric of society’ categories. This merging has no effect on the purpose of our study. The ‘foreign affairs’ variable covers the percentage of words addressing issues related to international relations and includes references to EU integration and post-accession conditionality and NATO accession. The ‘group-specific’ variable measures the percentage of words addressing the needs of ethnic minorities. Table 1 gives an overview of the categories.

Table 1. Content Categories in Support Agreements

In the second part of the empirical analysis, we study actual policy influence and support party behaviour. For this purpose, we select support agreements under two minority cabinets and analyse the behaviour of support parties. There are different strategies to select cases for a small-n analysis after analysing a larger number of observations. Hanna Bäck and Patrick Dumont (Reference Bäck and Dumont2007) argue in favour of case selection based on a large-n analysis. More concretely, they support the analysis of cases that are located at (or close to) the regression line in order to shed light on the causal mechanisms (see also Bäck et al. Reference Bäck, Meier and Persson2009; Gerring Reference Gerring2007). Our descriptive analysis does not allow a close application of this analysis due to the lack of sufficient cases, but we can select support agreements that fit the idea of predicted cases and still offer important variance on our main independent variable (support party type).

We increase the internal validity of our study by selecting cases that hold important confounding variables constant: the minority cabinets of Năstase I (2000–3) and Ponta I (2012). Both cabinets signed two support agreements each: one with a mainstream party and one with an ethnic minority group. Hence, the behaviour of the mainstream and ethnic minority parties can be directly compared without accounting for confounding variables such as time effects or the composition of the legislative party.

We are interested in the legal enactment of the content of the agreements as well as the existence of legislative initiatives regardless of their outcomes. We look at the content of the law, where this was the case, and identified its initiators. The outcomes are qualitatively interpreted. In addition, elite interviews with cabinet members and party leaders who witnessed the intricacies and negotiations of support for minority cabinets shed new light on how support parties differ in their behaviour. In particular, the experience of one former prime minister who was at the helm of a formal minority coalition cabinet provided key insights on the general type of requests made by minority groups beyond the written agreement and the negotiations for their support. Such insights are also used in the comparative discussion.

The pay-offs to legislative support parties under Romanian minority cabinets

In this section, we provide a short insight into the Romanian party system to introduce the main actors and provide a better understanding of the results of the empirical analysis below.

Main actors in Romanian politics

The Romanian party system came through the initial fragmentation of the early 1990s and can be considered relatively institutionalized, compared with the regional averages (Enyedi and Casal Bértoa Reference Enyedi and Bértoa2018). Parties themselves separated along the indicators of institutionalization or increased personalization (Coman Reference Coman2015; Soare and Gherghina Reference Soare and Gherghina2017) and became more predictable in their alliance building and rebuilding behaviour (Anghel Reference Anghel2017, Reference Anghel2018; Brett Reference Brett2015; Bucur et al. Reference Bucur, Cheibub, Martin, Rasch, Elster, Gargarella, Naresh and Rasch2018; Chiru Reference Chiru2015). Three decades after the transition to democracy, we can identify the main players in party politics with more clarity and identify institutionally driven patterns of behaviour similar to or diverging from those identified in studies of traditional democracies.

The main actors in the Romanian party system that survived the test of time are the Social Democrat Party (PSD), the National Liberal Party (PNL) and the Democratic Hungarian Union of Romania (UDMR). Their general fulfilment of institutionalization criteria (see Harmel et al. Reference Harmel, Svåsand and Mjelde2018) allows us to anticipate their persistence in Romanian politics (Anghel Reference Anghel, Harmel and Svåsand2019). Another party which largely fulfilled the criteria of an institutionalized party before merging with the PNL in 2015 was the Liberal Democratic Party (PDL). Through executive and legislative collaborations with non-institutionalized or ad hoc mainstream parties, these main actors were at the core of minority cabinets and engaged in formal and informal government support arrangements. Their patterns of engagement under minority governments and their effect on cabinet stability and policy outputs are the focus of this study.

In addition to these parties, there is another significant actor in the legislative majority building process in Romania that has so far been ignored by mainstream research. This is the National Minority Caucus (NMC) in the Chamber of Deputies. For the purpose of this study, the NMC has also been examined and analysed in a similar way to parties. The behaviour of this united and consistent group of politicians is not unlike that of a united, disciplined and institutionalized party. National minorities, according to Romanian law, are considered to be those groups of persons of a nationality other than Romanian who have legally constituted organizations, become members of the Council of National Minorities, a consultative governmental body, and have a representative in the parliament, following elections. The Council has constantly expanded its number from 13 organizations in 1990 to 19 since 2000. Throughout the analysed period, the number of minority representatives in the NMC has also fluctuated along similar numbers. Their voting is cohesive, they participate in official and informal consultations for government formation and policymaking as one unified group, and they have an elected leader and sign coalition and legislative support agreements as a single integrated assembly. On several occasions, the votes they had in the Chamber of Deputies have made the difference between one coalition outcome and another. Equally, the constant implicit and explicit legislative collaboration of all governments with the NMC has increased its visibility and substantiated its role as a unitary political actor without ever being included in the cabinet. Former cabinet members and one prime minister testified that a representative of the NMC was present for coalition meetings, starting in 2010.

Other parties that qualify as mainstream parties and are dealt with in this study are the Romanian National Unity Party (PUNR), the Greater Romania Party (PRM) and the National Union for Romania's Progress (UNPR). Let us now break down the principal differences between the numerous support agreements signed between these main actors in Romanian politics.

The content of explicit support agreements

In this part of the study we analyse and compare the content of explicit support agreements in Romania. There have been nine minority cabinets with explicit support agreements. From among these, two cabinets signed two different support agreements (Năstase I and Ponta I) and two cabinets worked on the same scheme of support with the NMC (Boc IV and Ungureanu). The length of the support agreements varies from 3,527 words (the Năstase government's agreement with the UDMR in 2003) to only 162 words (Ponta's agreement with the UNPR in 2012).

The visualization of a comparative analysis of the content of formal support agreements in Figure 2 confirms previously held beliefs that policy is the main driver behind such deals. Of the 10 agreements identified, seven had more than 50% of the body of the text allocated to policy deals. Offices such as junior ministerial posts have not been claimed by the UDMR or the NMC, but only by mainstream parties such as the PUNR, the PRM or the PNL. This is the first evidence that ethno-regional parties are more focused on policy deals than office positions. The inclusion of some functioning mechanisms also played an important role for the governments and the support parties as they have significant shares in all agreements. Similarly to previous claims made in the case of coalition agreements, these mechanisms ensure the administration of the cabinet and the cabinet's relation to a support party and enhance stability.

Figure 2. Content Comparison of All Formal Support Agreements

Note: Agreements with ethno-regional parties highlighted.

Going a level deeper into the categorization of the content of the policy deals, we can identify varying degrees of interest in policy areas across all documents (see Figure 3). Economic policies are covered by all support agreements, but there is some significant variation. The largest proportion of economic policies can be observed for policy deals between the Năstase government and the PNL in 2000 (around 60% of the policy content dealt with economic policies) and the Ponta cabinet with the UNPR in 2011 (68% of the policy deals were about economic policies). This is in line with the theoretical expectations as both support parties can be clearly identified as actors with a focus on the socioeconomic policy dimension.

Figure 3. Content Analysis within Policy Deals

Note: Agreements with ethno-regional parties highlighted.

Another factor that stands out is the focus on group-specific policies in all support agreements signed by the UDMR and by the NMC. The reason that the proportion of group-specific policy deals appears rather small in the 2011 agreement with the Boc government is that this support agreement with the NMC was part of the official coalition agreement between the three coalition partners. Hence, it covered not only the support deals but all coalition deals.

The observation of a strong group policy focus in deals with the ethnic minority parties pointed to a further difference between mainstream and ethnic party types along policy interests (see Figure 4). This led us to observe that there was a significant difference in overall concerns for group-specific policies for minority representatives (around 55% of the policy deals). The finding supports our main argument: ethnic minority parties try to ensure group benefits from the government but care less about national legislation.

Figure 4. Party Types and Policy Deals in Support Agreements

Case comparisons: evidence from support parties under two minority cabinets

From among our universe of cases, we selected two minority cabinets that benefited from the formal support of both a mainstream party and an ethnic minority party through written support agreements. These are Năstase I and Ponta I. The content of all four support agreements (see above) shows the expected distribution: the agreements with the mainstream parties (PNL and UNPR) concentrate considerably more on economic policy issues (33% and 42% respectively) than the agreements with the ethno-regional support parties (UDMR 8.5% and NMC 28%), while the ethno-regional parties focused in their agreements on group-specific policies (36%).

Năstase I (28 December 2000–19 July 2003): supported by the PNL and the UDMR

The Năstase cabinet lasted for 903 days, the longest-serving executive in post-communist Romanian history. It was a minority coalition cabinet formed around the main communist successor party, the PDSR (Pop-Eleches Reference Pop-Eleches2008). More importantly, it benefited from the initial legislative support of the PNL and the UDMR. A high-ranking member of the PDSR leadership at the time explained the process of deciding in favour of a minority government:

The PSD focused on developing an alliance aiming at parliamentary support that would allow us to govern alone. … The need to govern alone after the win in the elections was also driven by a pressure from below, from the party members in the territory, who did not want to share power now that they could have it all to themselves [after four years of opposition]. Only if finding support through a parliamentary coalition failed, the second option of a coalition government would have been considered.Footnote 2

A comparative analysis of the content of the agreements struck with the PNL and the UDMR, their impact and perceived utility by the political elites, identifies important contrasts in how the two supporters were perceived and what their interests were. The support agreement signed by the PNL with the PDSR was a pact of ‘non-aggression’. It meant that the PNL would not introduce a motion of no-confidence against the minority government as long as the cabinet continued a democratization agenda and economic improvements. In our interview, a member of the PNL leadership argued that it was meant as a contribution to ensure government stability during the dire economic situation of the early 2000s as well as keeping xenophobic parties out of power. The deal thus signed between the PDSR and the PNL, the principal party that symbolized the reborn opposition, was heavily criticized in the liberal media and within the PNL. It was not long before the PNL showed its discontent with the PDSR's lack of initiative to implement any of the economic, constitutional or electoral reforms agreed upon in the signed protocol.

Another interviewed member of the PNL leadership at the time admitted that there had also been an underground deal struck between the PNL and the PSD regarding offices still held by the PNL as outgoing members of the government: ‘The PSD was supposed to keep our men [at different levels of state administration]. We gave them a list. It was in fact a mistake, as we disclosed all our men on a silver platter. After we withdrew from the agreement, they eliminated all of them.’Footnote 3

The first working meeting between the PDSR and the PNL came three months after the agreement was signed. The PDSR was uncomfortable at the pressure exercised by the PNL for resources to be distributed their way. Upon seeing the state budget allocations of 2001, the PNL decided not to support the PDSR any longer and announced its return to active opposition.

The UDMR, on the other hand, was satisfied with the way its partnership with the PDSR was going. Negotiations for the support of the UDMR continued on a yearly basis throughout the life of the UDMR cabinet. A privileged witness from the PSD leadership, present during negotiations, remembers:

We were not worried that UDMR wanted positions in the cabinet. … What they were looking for now was some legitimacy within the community, i.e. more rights for minorities. Thus, they accepted this support scheme for the government and aimed at rights within the territory. In February 2001, a three-day ‘marathon meeting’ was held … The demands for minority rights of every county representative were heard.Footnote 4

The activity of the joint working group in the parliament was also appreciated by UDMR chairman Marko Bela, who made public statements that the UDMR had greater effectiveness as a support party. The budget that was not supported by the PNL was fast accepted by the UDMR, who admitted to receiving all the funds that it had requested.

The fact that the PDSR depended on the support of the UDMR made it complacent regarding the agenda put forward by the representatives of the Hungarian minority. A member of the PSD leadership remembers:

The protocol we agreed upon was followed step by step. In the first year, almost all issues in the agreement had been dealt with. Every Sunday, [the parties’ leadership] would meet. On Mondays, the issues they decided upon were discussed within the two parties so that within the same week problems could be solved through the parliament.Footnote 5

From the UDMR side, another witness explained the strength of the legislative coalition:

We know that coalitions die because they are built on informal ties. In 2000–4, even if we were not in government, we wanted the [legislative] coalition to work. We looked constantly to our political program and we wanted to see things done in our benefit.Footnote 6

The disciplined, steadfast negotiations between the PSD and the UDMR continued throughout the life of the single party minority cabinet Năstase II, with comparable outcomes. On 19 February 2003, a new agreement was signed between the PSD and the UDMR, renewing their promises of support for another year.Footnote 7 Important pledges were made by the PSD regarding its support for graduate studies in Hungarian at the Babeș Bolyai University in Cluj and a Hungarian television channel in Târgu Mureș. The resources allocated to the Hungarian minority also grew by a third in 2001 compared with 2000 and doubled in 2003 compared with 2002 (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Increase in Minority Resource Allocation

Ponta I (7 May 2012–9 December 2012): supported by the UNPR and the national minorities

The Ponta I cabinet was composed of the PSD, the PNL and the PC who had formed the Social Liberal Union political alliance (USL). The cabinet also received the support of the UNPR and the NMC, with which two separate agreements were signed. The small size of the agreements reflects the fast-forward process of formation of the Ponta I cabinet following a successful motion of no-confidence against the Ungureanu cabinet. The UNPR had in fact been a coalition member in the outgoing Ungureanu cabinet and the NMC had been supporting that same government composition for the previous three years. Both the UNPR and the NMC conditioned their support for the new Ponta cabinet on the immediate reversal of the austerity measures that previous governments had introduced. Salaries and pensions started to be increased by the Ponta government a week after assuming office. The UNPR also asked for the introduction of a solidarity tax on wealth and a revision of the electoral law, which were never enforced.

Beyond its policy requests, however, the UNPR negotiated for its inclusion in an electoral alliance with the PSD first – and the whole of the USL later – that guaranteed its otherwise improbable entrance into parliament in the upcoming legislative elections. It was also aiming to join the government that Ponta was going to form after the upcoming elections. The UNPR was indeed included in the Ponta II cabinet in December 2012. This office- and material-seeking behaviour of the UNPR was a constant of its alliance-building strategies. The UNPR had originated from a group of ‘unaffiliated’ parliamentarians who had left their party of origin and provided legislative support for the minority Boc II and III cabinets.Footnote 8 It was included officially in the Boc IV and Ungureanu minority cabinets after the informal group was registered as a party.

On the other hand, the NMC had a more direct interest in the allocation of resources and group-focused policies. In the support protocol, the NMC asked for the development of a government strategy to improve the situation of the Roma population and the adoption of a law regulating minority status. The ‘Strategy for the Integration of Romanian Citizens Belonging to the Roma Community’ was discussed throughout the years, only to be finally adopted in 2014. The law on the status of minorities, however, continues to be a point of contention. This particular piece of legislation has been halted in parliament commission debates since 2005, regardless of the constant demands of all minority representatives for some progress.

In addition, the NMC has a track record of supporting all types of governments, regardless of ideological positioning, without acquiring offices. Throughout its activity in the parliament, it aligned its votes with the victor of the day. It makes pragmatic switches from one political camp to the other in order to continually promote its group-focused interests. Prime Minister Ungureanu remembered how he lost the support of the NMC when it switched sides to support the Ponta I cabinet:

In view of the vote for the motion of no-confidence, I spoke with all government supporters. The NMC leader did not admit having alternative arrangements. But they did not believe our side could deliver on their policy requests any more. They knew the opposition had the first chance to form the following cabinet and chose strategically.Footnote 9

The role of the NMC in the fall of the Ungureanu government and the favourable vote received by Ponta was also acknowledged by another former ally of theirs, Prime Minister Boc. He stated after the vote that the ‘NMC stabbed the government in the back’; it could not have fallen otherwise (Mediafax 2012a). The motion received 235 votes (it only needed 231 to pass). The NMC had 17 votes at the time. The leader of the NMC, Varujan Pambuccian, declared that he was offered a ministerial portfolio in the Ponta cabinet, but he refused. Pambuccian stated that he was always offered a ministerial position to secure the group's loyalty but that ‘he is a good strategy man, and not a man for the administration’ (Mediafax 2012b).

Conclusion

This empirical study concentrates on the effect of party type on policy bargaining outcomes in support agreements and the actual behaviour of support parties under minority governments. Previous research has rarely focused on differences between support parties and consequently on how this affects their behaviour under minority governments.

The results of our two-part empirical analysis indicate that ethno-regional parties try to achieve more group-specific policies and are less interested than mainstream parties in securing office positions or policy pay-offs on the traditional socioeconomic dimension. We observe that, through their strategy of offering legislative support, minorities benefited from a constant increase in funding and attention to their specific needs. However, the implementation of some of the most important policy demands of minorities’ representatives is constantly halted by prioritizing the electoral concerns of mainstream parties. On the other hand, in exchange for their support, mainstream parties are more office- and vote-oriented and desire side payments such as junior positions in the administration or membership of future cabinets. Moreover, they want to influence economic and social policies since these are the policy dimensions they compete on.

Our results shed light on the relationship between minority governments and support parties. They are not only interesting for scholars of party competition and coalition governments, but also have important implications for scholars of ethnic minority parties and the substantive representation of ethnic minorities. We show that ethno-regional parties indeed defend their electorates’ interests, a conduct often doubted by previous research. While our in-depth within-case analysis offers strong internal validity, we are aware that the research on (support) party behaviour under minority governments would benefit greatly from a larger country selection and quantitative data analyses where different factors can be estimated. A study of differentiations of party types within the ‘ethno-regional’ category is a further avenue of research. A comparative investigation of the pay-offs for the same ethno-regional parties in government and outside would further refine these results.

Supplementary information

To view the supplementary information for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2019.11

Acknowledgements

We thank Hanna Bäck and David Willumsen as well as the participants of the panels on coalition cabinets at the ECPR General Conference 2018 and DVPW Congress 2018 for valued comments and suggestions. We thank Laurențiu Ștefan for sharing his access to some of the interviewed Romanian elites. We are especially grateful to the three reviewers whose suggestions strengthened this study. All errors remain our own.