Japan, the leading non-Western liberal democracy, is routinely denounced with regard to immigration: every policy in this area seems to draw international scrutiny, if not outright criticism. Much the same happened during the Great Recession of the late 2000s, when Japan's government announced an initiative to fund the voluntary repatriation to Latin America of unemployed Latin American workers of Japanese descent and their families. The 2009 announcement stirred considerable controversy. Major media outlets worldwide, including the New York Times and Time, reported that Japan was paying foreign migrants to ‘go home’. For many observers, ‘the plan came as a shock’ and was seen as ‘baffling’, ‘cold-hearted’ and ultimately a ‘disgrace’ (Tabuchi Reference Tabuchi2009; see also Arudou Reference Arudou2009; Masters Reference Masters2009). It epitomized what is often regarded as ‘Japan's at best illiberal immigration policies’ (Cortazzi Reference Cortazzi2015).

Notwithstanding the specifics of the Japanese case, in the larger context the initiative was hardly exceptional. After the global economic downturn, other liberal democracies introduced similar programmes for unemployed migrant workers (McCabe et al. Reference McCabe2009). Even if relatively unknown, ‘state-induced returns’ (Koch Reference Koch2014) of foreign migrants – dubbed by some as ‘soft deportation’ (Kalir Reference Kalir, Vathi and King2017; Leerkes et al. Reference Leerkes, van Os and Boersema2017) – have become a common feature of global migration. The recession resurrected measures that had been implemented decades earlier in Western Europe in the aftermath of the 1973 oil shock (Black et al. Reference Black, Collyer and Somerville2011). European states were the first to launch non-coercive, financially assisted repatriation of their foreign workers. Over time, such schemes embraced various categories of irregular migrants. Under the auspices of the International Organization for Migration (IOM), they spread to other parts of the world. In 2009 – the year Japan's proposal made the headlines – 32,000 assisted repatriations occurred worldwide. After reaching nearly 100,000 in 2016, the programmes expanded to involve more than 100 sending states (IOM 2018).Footnote 1

Despite this rapid advance, however, assisted repatriation remains understudied as a political phenomenon. The issue has mainly been tackled from a bottom-up perspective that centres on migrants’ experience. This article, in contrast, redirects the focus to the issue of state policy and raises key state-centric questions: Why has assisted repatriation become so popular? What motivates states to implement such measures – that is, what are the conceptual underpinnings of this policy? In addressing these questions, the article makes two contributions. First, it provides an overview of assisted repatriation from its inception in the 1970s to the present by demarcating five phases in the conduct of this policy. Second, it explains the phenomenon's conceptual roots and the reasons for its expansion. Contrary to the conventional view that associates this growing practice with the neoliberal marketization of belonging, I argue that assisted repatriation is better conceptualized as a subset of immigration control policies rooted in the liberal ideals that imbue the institutional orders of liberal democracies. Short of defusing all tensions in liberal theory and practice, from the state's perspective, these post-arrival measures are more attuned to migrants’ rights and hence provide a palatable alternative to the forcible management of unwanted migrants. This argument is developed using primary and secondary sources in multiple languages, including data sets from Freedom House (2000–18) and the IOM (2000–18). I substantiate my contention with evidence from the case of Japan, which is an underexplored newcomer to this policy. The article concludes with recommendations for further research on the causal pathways of this phenomenon.

Assisted repatriation: an overview

In recent decades, governments worldwide have begun to promote assisted repatriation of their hosted migrants. Such programmes are designed to provide financial, administrative, logistical and, at times, additional reintegration support to those who ‘volunteer’ to return to their country of origin (Kuschminder Reference Kuschminder2017). According to Richard Black et al. (Reference Black, Collyer and Somerville2011), these schemes target four categories of migrants: (1) those with valid residence; (2) illegal residents and failed asylum seekers who are not yet subject to removal; (3) unauthorized migrants subject to removal, including rejected asylees; and (4) asylees whose claims are pending. The extent of support provided varies across implementing states, but participants generally receive help in obtaining travel documents and counselling before departure, as well as airfare and cash allowances in the transportation stage. When programmes have an added reintegration component, returnees receive extra support, such as vocational training, job placement and housing support in the home country (Kuschminder Reference Kuschminder2017).

National governments are responsible for the development of their assisted repatriation programmes, but they are increasingly implemented in cooperation with the IOM. Using its expertise and transnational network, the IOM works with non-governmental partners to enact what is known as assisted voluntary return and reintegration (AVRR). When it does not administer such projects, state authorities responsible for immigration enforcement are usually the implementers. Examples are the French Ministry of the Interior's Office for Immigration and Integration and the UK's Home Office (EMN 2015). Over the past decades, assisted repatriation has evolved in stages. Although their boundaries are not sharp, we can delineate five phases of this phenomenon.

The 1970s: supporting foreign workers

Full-fledged, financially assisted repatriations were introduced in Western Europe during the post-1973 economic recession (Black et al. Reference Black, Collyer and Somerville2011; Gubert Reference Gubert and Lucas2014). With declining labour demand and rising anti-immigrant sentiment, several states offered support to foreign workers who agreed to leave (Brücker et al. Reference Brücker, Boeri, Hanson and McCormick2002; Stalker Reference Stalker2002). The Netherlands, for instance, ratified its Reintegration of Emigrant Manpower and Promotion of Local Opportunities for Development scheme in 1974 (Black et al. Reference Black, Collyer and Somerville2011; Gubert Reference Gubert and Lucas2014). France started a similar programme in 1977: the Aide au Retour (Help to Return) provided 10,000 francs (approx. €1,500) and travel expenses to non-European Community migrant workers willing to exit France's social security system and return home. In 1975, German states initiated voluntary returns for their guest workers, and in 1983, under the Act to Promote the Preparedness of Foreign Workers to Return, two repatriation schemes were enacted at the federal level. The first reimbursed returnees’ social security contributions; the second provided 10,500 marks (approx. €5,350) per adult and 1,500 marks per child to assist in their return. Although the impact of these ‘golden handshake’ schemes was arguably limited (Black et al. Reference Black, Collyer and Somerville2011; Gubert Reference Gubert and Lucas2014; Hollifield Reference Hollifield1992; Webber Reference Webber2011; Widner Reference Widner1980), the idea of assisting returns did not lose its appeal for policymakers and was soon extended to embrace another category of migrants.

The 1980s: supporting asylum seekers

Throughout the 1980s, several European countries developed assisted repatriation programmes that targeted asylum seekers, thereby conflating policies for labour and humanitarian migrants (Noll Reference Noll1999). In 1979, Germany enacted the Reintegration and Emigration Programme for Asylum Seekers in Germany (REAG) (Schneider and Kreienbrink Reference Schneider and Kreienbrink2010). Belgium implemented a similar scheme in 1984, the Return and Emigration of Asylum Seekers ex-Belgium (REAB), for failed asylees, undocumented migrants who had not applied for asylum, and those who had abandoned their asylum claims (Fedasil 2009). The Return and Emigration of Aliens from the Netherlands programme was launched in 1991 for both undocumented and legal migrants who wished to return (Beltman Reference Beltman and Vonk2012). The same year, France launched its Aide au Retour Volontaire scheme for rejected asylees and foreign illegal residents (Gubert Reference Gubert and Lucas2014). At that time, assisted repatriation programmes offered limited support, such as travel expenses and pre-departure counselling, and were used as a ‘social instrument that created opportunities for migrants to return under better circumstances’ (Lietaert et al. Reference Lietaert, Broekaert and Derluyn2017: 972; Vandevoordt Reference Vandevoordt2017). In the 1990s, however, states began to use such schemes more overtly as a tool of migration management.

The 1990s–2000s: managing irregular migration

The demise of the bipolar world order led to a spike in migratory flows, which resulted in new approaches to security (Doty Reference Doty1998; Weiner Reference Weiner1996) and placed migration policy high on national agendas (Bloch and Schuster Reference Bloch and Schuster2005; Lindstrøm Reference Lindstrøm2005). Europe worked harder to accelerate the removal of irregular migrants whose countries of origin were deemed safe, and the number of assisted return schemes grew to more than 20 in 2004. By 2009, they had been mainstreamed into EU policy, with member states agreeing to promote the voluntary repatriation of illegal migrants (European Parliament and the Council 2008). Simultaneously, governments began to augment their schemes with reintegration funds. For example, in 2002 Germany combined its REAG scheme with the 1989 Government Assisted Repatriation Programme (GARP), offering post-return aid of up to €500 (Schneider and Kreienbrink Reference Schneider and Kreienbrink2010). In the 2000s, Belgium supplemented its REAB scheme with reintegration support of up to €1,750 (Fedasil 2009). In this phase, the policy's rationale shifted ‘from facilitating return to proactively convincing or inducing people to return through providing financial incentives’ (Vandevoordt Reference Vandevoordt2017: 1913; emphasis in original), and the practice began to spread beyond Europe to countries such as Australia and South Africa.

2008–2009: supporting foreign workers – revival

In the wake of the 2008 global recession, in a move reminiscent of the post-1973 economic slowdown, several states revived assisted repatriation for their foreign workers who were experiencing difficulties with employment. Most notably, the Japanese government implemented its first programme, which targeted co-ethnic workers from Latin America (Nikkeijin). The Repatriation Support Project for Unemployed Nikkeijin offered ¥300,000 (approx. $3,000) to a returnee and ¥200,000 to each dependant for airfare (Arudou Reference Arudou2015). Spain enacted the Programa de Abono anticipado de Prestación a Extranjeros (APRE, Programme for Early Payment of Unemployment Benefits to Foreigners), which offered unemployed non-EU migrants one-way tickets and unemployment benefits of up to €8,100 (McCabe et al. Reference McCabe2009; Plewa Reference Plewa2009). Also, the Czech Republic sanctioned assisted repatriation to prevent unemployed non-EU migrants from entering the underground economy. The scheme covered transport, temporary accommodation and a return allowance of up to €850 (McCabe et al. Reference McCabe2009). Notwithstanding this resurgence of assisted repatriation to facilitate returns, states have progressed on a path towards more effective use of projects actively to induce the repatriation of unwanted migrants.

The 2010s: managing irregular migration – expansion

In the 2010s, international migration emerged as one of the most divisive public policy issues in the developed world. To alleviate the pressure of heterogeneous migrant flows, states turned to multiple pay-to-go schemes enhanced by reintegration payouts that targeted specific categories of migrants. For example, as early as 2009, the UK supplemented its Voluntary Assisted Return and Reintegration programme with special packages for irregular migrants from Iraq, Afghanistan and Zimbabwe, and launched the Assisted Voluntary Return for Families and Children scheme (Black et al. Reference Black, Collyer and Somerville2011). Europe's 2015 migrant crisis expanded these national responses, despite the EU's call for ‘common standards’ (EMN 2016; European Commission 2017). Overwhelmed by the volume of asylees and unable to enforce the return of rejected applicants, European states adopted a mixture of policies that incentivized returns. For example, in 2017 Germany allocated a budget of €40 million to the StarthilfePlus (Start-Up Cash Plus) programme, which builds on the REAG/GARP scheme and provides a bonus of €1,200 to those who leave before receiving their asylum decision and €800 to those who forgo the right to appeal after rejection (BMI 2017). Germany also implemented a temporary programme, Dein Land. Deine Zukunft. Jetzt! (Your Country. Your Future. Now!), which offered reintegration aid of up to an additional €3,000 for housing in the returnee's home country (Hussein Reference Hussein2017). In 2018, Germany committed to financing jobs and training for returnees to Afghanistan, Nigeria, Tunisia and Iraq (InfoMigrants 2018). France and Austria also raised their return and reintegration benefits (Bulman Reference Bulman2016; Farand Reference Farand2017). In contrast, Sweden scrapped its policy of providing failed asylees a monthly cash benefit of 1,200 kronor (approx. $130) and housing, which triggered a push to enrol in its assisted repatriation scheme (Bengtsson Reference Bengtsson2016; Rogberg Reference Rogberg2017). In Belgium and the Netherlands, authorities induced assisted repatriation by disseminating information about the long procedure, lack of housing and poor living conditions (HLN 2016; Zandstra Reference Zandstra2015). The last decade has witnessed states’ vigorous efforts to induce assisted returns and such programmes’ growing variety and outreach, which have rendered the practice a global phenomenon (IOM 2011, 2016, 2017, 2018).Footnote 2

Summary

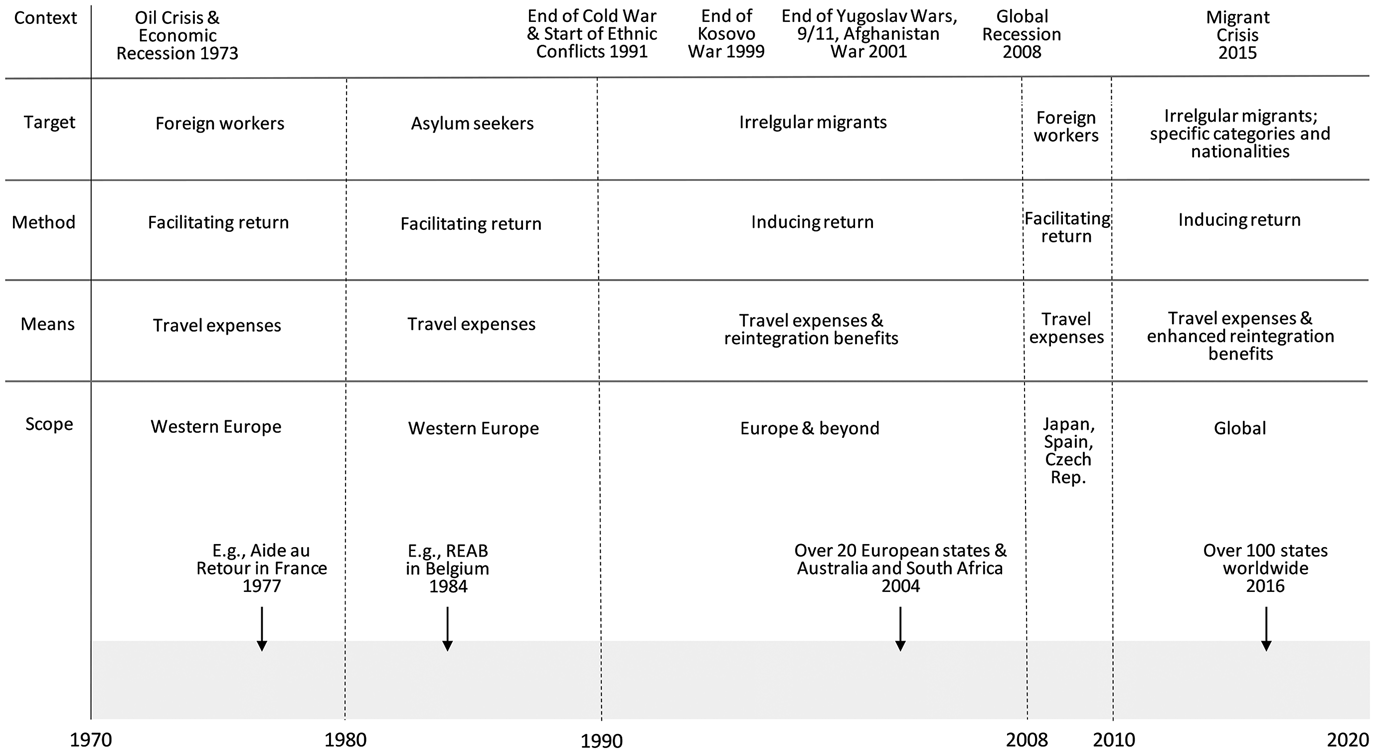

As a policy for coping with foreign residents, assisted repatriation has evolved over decades. From its beginnings as a way to facilitate the return of foreign workers during a period of economic stagnation in Western Europe, it has become an overt instrument for inducing the return of irregular migrants globally. The expansion of the policy's target recipients, methods and means of support, and geographic scope is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Evolution of Assisted Repatriation

Assisted repatriation as a political phenomenon

Although increasingly widespread, assisted repatriation remains underexplored as a political phenomenon. Efforts have largely been geared towards understanding what motivates migrants to accept repatriation offers. The consensus is that the decision is highly complex. For instance, Khalid Koser and Katie Kuschminder (Reference Koser and Kuschminder2015) find that conditions in the destination country are the key factor, whereas Black et al. (Reference Black, Koser and Munk2004) identify pull factors in home countries as more important than push factors. According to Anne Strand et al. (Reference Strand2008), the desire to avoid forced deportation drives migrants’ decision to repatriate voluntarily. To further complicate the matter, Jan-Paul Brekke (Reference Brekke2015) has established that the likelihood of accepting assisted repatriation depends on characteristics such as gender, age, family status and the country of origin. Marie-Laurence Flahaux (Reference Flahaux2017), in contrast, argues that this depends on the migrant's prospects of future mobility. Scholars have also assessed the sustainability of assisted repatriation, particularly in a European context (DeBono Reference DeBono2016; Hammond Reference Hammond and Fiddian-Qasmiyeh2014; Scalettaris and Gubert Reference Scalettaris and Gubert2019). Such research tends to examine country-specific schemes, including those of Norway, Belgium and the UK (Lietaert Reference Lietaert2017; Oeppen and Majidi Reference Oeppen and Majidi2015; Strand et al. Reference Strand2016). Some have questioned the voluntary nature of financially induced returns (Blitz et al. Reference Blitz, Sales and Marzano2005; Dünnwald Reference Dünnwald, Geiger and Pécoud2013; Webber Reference Webber2011), while others debate the ethical basis of such policies (Gerver Reference Gerver2017). Finally, effort has been made to examine the role of civil (Kalir Reference Kalir, Vathi and King2017; Vandevoordt Reference Vandevoordt2017) and intergovernmental (Ashutosh and Mountz Reference Ashutosh and Mountz2011; Koch Reference Koch2014; Webber Reference Webber2011) actors in assisted repatriation.

Less analytical attention has been paid to what motivates states’ behaviour. Early on, the use of assisted repatriation was attributed to humanitarian and pragmatic considerations. For instance, Black et al. (Reference Black, Collyer and Somerville2011: 3) assert that pay-to-go schemes appeal to states because ‘they are cheaper and more humane than forced returns, [… and] therefore economically, politically, and morally more palatable’. Although not unsound, such claims do not identify the deep conceptual roots of this policy. Given the financial nature of the transaction involved, it is tempting to see this phenomenon as deriving from the notion of a ‘neoliberal political economy of belonging’, which is manifested by the growing marketization of the state-migrant relationship (Mavelli Reference Mavelli2018). Barak Kalir (Reference Kalir, Vathi and King2017) promotes such reasoning. Drawing on research on a civil society's experience in Spain, his account rests on the following premises: assisted repatriation is driven by the economic rationale of migrant selection rooted in market logic; migrants’ decisions lack voluntarism because the idea of ‘“voluntary return” springs from the trope of neoliberalism, which champions rational and free choice’; and states incorporate civil society organizations into ‘the state logic and its neoliberal ideology’ to turn migrant returns from below into ‘soft deportation’, while the IOM legitimizes them from above to promote states’ ‘neoliberal’ agendas (see also Ashutosh and Mountz Reference Ashutosh and Mountz2011; Georgi Reference Georgi, Geiger and Pécoud2010). In short, this view asserts that assisted repatriations’ instrumentality ‘reveals the deeper neoliberal ideological underpinnings of such programmes as part of the “migration apparatus”’ (Kalir Reference Kalir, Vathi and King2017: 56–57).

However insightful, this account must be approached with caution. Neoliberalism is a fuzzy concept that is hard to pin down – but even as delineated above, the alleged ‘neoliberal’ foundations of assisted repatriation are shaky. It is hard to see, for example, the logic of migrant selection as a distinctive neoliberal marker. Selectivity has been the core feature of modern migration regimes (de Haas et al. Reference De Haas, Natter and Vezzoli2018; Ellermann and Goenaga Reference Ellermann and Goenaga2019). Despite claiming a high moral ground, states pursue entry policies in line with their national interests and objectives. Even humanitarian admission, which by definition is meant to be immune to such logic, is primarily dictated by states’ self-interest (Gammeltoft-Hansen and Tan Reference Gammeltoft-Hansen and Tan2017). More fundamentally, the answer to the key question of the rationale and mechanisms of adopting an assisted repatriation policy remains elusive.

Accepting that assisted repatriation is based on the ‘logic that champions state sovereignty’ (Kalir Reference Kalir, Vathi and King2017: 57), I argue that it is better explained as a subset of immigration control policies rooted in the liberal outlook on individual rights imbued in liberal democracies. Certainly, the question of liberal governance of migrants in liberal democracies is complex and contentious, both in theory and, even more so, in practice. Some suggest that the natural extension of the liberal logic premised on the universality of human rights is open borders (Carens Reference Carens1987). Yet border control is real – even in the world's most open states. Phillip Cole (Reference Cole2000) argues that a fully liberal immigration policy is merely an aspirational ideal. With the asymmetry between entry and exit, limits on in-migration mean that liberalism ‘comes to an end at the national border’, and hence ‘there is no strategy of membership control that can be consistent with central liberal principles’ (Cole Reference Cole2000: 13, 193). Consequently, what constitutes access to and membership in a contemporary liberal state is vigorously debated (Adamson et al. Reference Adamson, Triadafilopoulos and Zolberg2011; Chauvin and Garcés-Mascareñas Reference Chauvin and Garcés-Mascareñas2014; Kiwan Reference Kiwan2005; Thomas Reference Thomas2002).Footnote 3 What complicates this debate is that national migration management is driven by multiple, often contradictory, forces seeking different goals (Boswell Reference Boswell2007; Boswell and Geddes Reference Boswell and Geddes2010; Freeman Reference Freeman1995; Hampshire Reference Hampshire2013; Hollifield Reference Hollifield2004; Kalicki Reference Kalicki2019a, Reference Kalicki2019b; Menz Reference Menz2009; Paul Reference Paul2015; Perlmutter Reference Perlmutter1996), which contributes to the liberal democratic state's general incoherence on immigration affairs.

Nevertheless, liberal developments in migration policy are, overall, on the rise (de Haas et al. Reference De Haas, Natter and Vezzoli2018; Helbling and Kalkum Reference Helbling and Kalkum2018). Although assisted repatriation is a regulatory instrument, I argue that its growth is congruent with this general trend. From the state's perspective, this policy mitigates the pressing need for border control in the world's democracies in a manner consistent with a demand for the application of rights-based liberal measures (Cornelius et al. Reference Cornelius2004; Hollifield Reference Hollifield1992, Reference Hollifield2004). Its liberal disposition is evidenced by the degree of choice extended by a more powerful state to a resident non-member: in exchange for financial compensation, the non-citizen may forgo her claim to residence in the state's territory. The two parties can implicitly agree to trade their self-serving and competing notions of liberty – which, at least symbolically, enables the state to achieve its policy objectives without actively violating its commitment to basic liberal principles.Footnote 4 In practice, this is fostered by the institutional logic of the liberal democratic polity.

If this reasoning is correct, this phenomenon should be particularly prevalent in states committed to individual liberties. This is, indeed, the case. As shown earlier, this policy was initiated in and, for a long time, confined to Western Europe before spreading outwards with the help of the IOM, whose stated mission is to ‘enhance the humane and orderly management of migration and the effective respect for the human rights of migrants’. According to Freedom House's classification of countries in terms of the ‘real-world rights and freedoms enjoyed by individuals’, which includes the protection of human rights, the practice was exclusive to ‘free’ states (liberal democracies) until 2001. The IOM's data on state-assisted voluntary returns correlated with Freedom House's rankings reveal that semi-liberal and illiberal states – classified as ‘partially free’ and ‘not free’, respectively – have only come on board in recent years (Figure 2). Yet despite a more than decade-long ‘decline in global freedom’ that has resulted in a global predominance of non-liberal states (Freedom House 2019),Footnote 5 close to half of all states that used assisted repatriation in 2017 were liberal democracies (followed by semi-liberal states). Of Freedom House's top 10% of the world's freest countries (20 states), all but two pursued this policy that year with the IOM's support.Footnote 6

Figure 2. Assisted Repatriations by Country Status, 2000–17

However, this hardly tells the full story. Most non-liberal states repatriate only tiny numbers of migrants through financial inducements. There are a few notable exceptions, such as Turkey, Niger, Morocco, Djibouti and Yemen. If we consider the actual numbers of assisted returns, the picture is clearer and even more compelling. When the policy evolved into an instrument for inducing returns in the post-Cold War turmoil, the numbers skyrocketed. Germany alone voluntarily repatriated more than 270,000 migrants in 1998 (versus 35,000 forcible removals). This number declined in Europe to about 75,000 in 2000 (68,000 for Germany alone), after which it plateaued (IOM 2004). Despite their gradual expansion to non-liberal regimes, in 2017 ‘free’ states were still responsible for nearly three-quarters of all assisted repatriations (Figure 3). In that year, the top 10% of them conducted about 60% of all assisted repatriations that involved the IOM. But even this fails to capture the full magnitude of the phenomenon. Institutionally functional democracies often manage assisted repatriation without the IOM's support, thereby rendering the proportion even more in their favour. To illustrate, over 8,400 migrants were returned voluntarily from Sweden in 2016 via the Swedish Migration Agency (versus 1,400 forced returns; Migrationsverket 2018), while IOM-assisted returns amounted in that year to 11.Footnote 7 This is, of course, not to ignore the fact that assisted repatriations also occur in non-liberal states; yet it is highly revealing that even though the vast majority of unwanted migrants are hosted by non-liberal regimes (Munck Reference Munck2008), the practice of assisting their return through financial incentives has been disproportionally associated with politically open states.

Figure 3. Assisted Repatriations by Numbers, 2000–17

This finding is highly indicative but not conclusive; we do not know whether free states are guided by the logic anchored in migrant rights or resorting to neoliberal tactics. This only becomes apparent when we take a closer look at the assumptions and rationales that inform the two accounts. The central premise of the neoliberal perspective is that in the market-driven selection of migrants, ‘the lack of real choice is […] a key ingredient to the success’ of assisted repatriation programmes; that is, the migrant's acceptance of the repatriation offer effectively ‘rests on there being no other choice’ (Webber Reference Webber2011, cited in Kalir Reference Kalir, Vathi and King2017: 66) than ‘an expected forced deportation’. In contrast, the liberal account does not reach an absolute conclusion on this matter, because it recognizes that assisted repatriation has served different goals and targets migrants with both legal and illegalized status. This is consistent with findings that migrants’ decisions are variable, complex, and induced by incentives and disincentives. The studies cited above reveal that they consider diverse factors, and a threat of forcible expulsion, if present, is often not critical. For example, legal migrants often apply for assisted repatriation despite being under no direct or implied threat of forcible removal. Consider that before 1982, about 60,000 employed Portuguese and Spanish workers and their families renounced their residency and working rights in France to become beneficiaries of the Aide au Retour scheme (Plewa Reference Plewa2009). More recently, 7,000 foreign workers applied, and 5,400 were approved, for Spain's ‘fully voluntary’ APRE programme as of May 2010; that is, during its initial 19 months of operation. Although this constituted only a small portion of potentially eligible applicants, the government considered the programme a ‘success’ (Papademetriou et al. Reference Papademetriou2010: 109–110; Plewa Reference Plewa2012). Regardless of how success is conceptualized and measured, what is important here is that many such schemes advanced the recipients’ choice – a point I will return to in my discussion of Japan's Latin American workers.

The picture is less clear regarding irregular migrants. In this case, the neoliberal outlook seemingly gains more currency. However, the liberal view also recognizes that irregular migrants, ranging from rejected asylees to visa overstayers and from victims of trafficking to illegal entrants, may indeed be subject to forced deportation. The unanswered question is why a liberal democratic state would seek to employ ‘soft deportation’ to remove unauthorized migrants rather than exercise its constitutive prerogative on the use of force. Unlike its neoliberal counterpart, the liberal approach provides an answer. As Matthew Gibney and Randall Hansen (Reference Gibney and Hansen2003) note, border control involves the capacities ‘to block the entry of individuals to a state, and to secure the return of those who have entered’, both of which ‘sit uneasily with liberal principles’. Yet it is ‘forcible expulsion from the national territory’ that is most problematic, as it ‘requires bringing the full powers of the state to bear against an individual’. This ‘cruel power’ is ‘the state's ultimate and most naked form of immigration control’, which ‘goes directly to the heart of concerns raised by liberalism, democracy and human rights’ (Gibney and Hansen Reference Gibney and Hansen2003: 1; Gibney Reference Gibney2008: 147). Thus, although not deemed illegitimate (Gibney Reference Gibney2013), deportation is ‘incompatible with the modern liberal state based on respect for human rights’ (Gibney Reference Gibney2008: 147; see also Ellermann Reference Ellermann2010; Lenard Reference Lenard2015). From this perspective, voluntary repatriation, ‘in which individuals are encouraged – often through a combination of carrot and stick measures – to return to their countries of origin’ (Gibney and Hansen Reference Gibney and Hansen2003: 2–3), emerges as an alternative post-arrival measure that does not blatantly contravene the liberal state's bedrock values in the effort to maintain border integrity through operation of the immigration control system.

I am far from suggesting that unilateral deportation is becoming an obsolete practice; an alternative does not equal replacement. Violence is constitutive of the state's sovereignty and its last word; liberal states retain every power to guard their borders through the enforcement of immigration laws. They may increasingly strive to assist irregular migrants in order to render their returns consensual, but as migrants’ unauthorized presence grows, so may the threat of forcible removals. Put simply, regardless of how contentious the practice may be, a liberal state ‘needs deportation’ because it ‘furthers the myth’ of its capacity to manage unlawful migrants (Gibney and Hansen Reference Gibney and Hansen2003: 15). A statement by Thomas de Maizière, Germany's federal minister of the interior, in the midst of Europe's migration crisis captures it well. Announcing Germany's intention to increase the voluntary return of those with ‘no right to stay’ through StarthilfePlus, he stated: ‘I appeal to insight and reason: for all those who do not have prospects in Germany, the voluntary departure from a deportation represents the better way. If the possibility of a voluntary return is not used, only the instrument of deportation remains. For only with consistent application of the law can the functioning of our asylum system be ensured’ (BMI 2017).

However, the problem of forcible expulsion from liberal democracies is not merely ideational. Unlike the neoliberal view, the liberal perspective identifies factors that motivate a state's adoption of assisted repatriation. It accepts that the rise of international human rights norms has been consequential for the conduct of state affairs (Finnemore and Sikkink Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998; Risse and Sikkink Reference Risse, Sikkink and Risse1999), including immigration affairs (Jacobson Reference Jacobson1996; Soysal Reference Soysal1994). In practice, however, reluctance to use forced deportation is a function of the internal institutional features of a liberal democratic polity which translate the rights of a state's non-citizen residents into concrete action. The first is associated with the judicial power to limit forcible removals: as Christian Joppke (Reference Joppke1998) explains, by invoking the human rights of foreign residents, domestic courts impose the principle of ‘self-limited sovereignty’ (see also Joppke Reference Joppke2001). The second is the state–public relationship regarding coercive immigration measures – ‘the fickle and unstable nature of public opinion’ during the policy process (Gibney and Hansen Reference Gibney and Hansen2003: 2). Antje Ellermann (Reference Ellermann2006, Reference Ellermann2009) argues that even if the public is supportive of strict legislative safeguards, it may be uncomfortable with the expulsion of resident aliens at the policy implementation stage. The third feature is the increased political and legal advocacy of civil society actors on behalf of foreigners with residential ties to the host society (Ambrosini and van der Leun Reference Ambrosini and van der Leun2015; Hadj Abdou and Rosenberger Reference Abdou L and Rosenberger2019). Immigration authorities in liberal democracies are constrained by these realities: formal authority notwithstanding, their capacity to invoke forcible deportation is inhibited.

Evidence from Japan

Can we trace the logic of assisted repatriation presented above and demonstrate its conditions of formation? I will use an illustrative example. The underexplored case of Japan is particularly suitable here. Although Japan is the most liberal non-Western democracy,Footnote 8 it is not popularly associated with liberal migration management practices. For instance, the Japanese state has been accused of ‘iron-fisted treatment’ of its irregular foreign residents (Fritz Reference Fritz2019). Nevertheless, the country is a latecomer to assisted repatriation. Indeed, the last decade of Japan's conduct constitutes a microcosm of this policy's evolution in a magnified manner, and hence offers a wealth of data. It highlights its practical iterations and conceptual underpinnings. Since the relevant scholarship remains Western-centric, focusing almost exclusively on Europe, a case study of Japan also yields illuminating theoretical insights into research on the expansion of this phenomenon in liberal democracies. My examination draws on public and government sources, which include data obtained through personal interviews and correspondence with Japanese policymakers and policy insiders.

Liberal immigration measures gain traction slowly in Japan. Like its European counterparts, albeit 30 years later, Japan offered to support the return of foreign workers during the economic slowdown of the late 2000s; as noted above, in 2009 it initiated the assisted repatriation scheme for Latin American workers of Japanese descent and their families. The programme was implemented by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare against the backdrop of deteriorating conditions for Nikkei workers, such as growing unemployment and unstable living conditions. Fearing the rise of crime (including organized crime), the security-minded Ministry of Justice (MOJ), which controls immigration, endorsed the scheme and supported its operation.Footnote 9 However, these workers and their families, whose legal presence in Japan was secured by renewable residential visas, were not at risk of forcible expulsion. Nonetheless, from the population of approximately 350,000 documented Nikkei Brazilians and Peruvians, of whom an estimated 140,000 became unemployed (McCabe et al. Reference McCabe2009), 21,675 applicants had been approved for assisted repatriation by the programme's end in March 2010 (MHLW 2010). That is, an estimated 15% of the eligible migrants, or about 6% of the total Nikkei population, embraced the Japanese state's offer. Many Nikkei workers left on their own, while most chose to remain in Japan. These numbers can be interpreted in different ways, but the main point here is that participation in the programme was optional. From the state authorities’ perspective, the return of unemployed Nikkei workers could only be enforced by promoting and facilitating voluntary departure in line with a ‘humanitarian point of view’.Footnote 10 Ironically, the widespread condemnation of Japan's government came after it extended the more liberal return measure to foreign workers who had been admitted based on racial preference (Kalicki Reference Kalicki2019b).Footnote 11

As in Europe, Japan's policy has evolved into a more overt tool for inducing the return of irregular migrants. Intended to ‘drastically reduce the number of illegal foreign residents’, in 2004 the revised immigration law established a departure order system (ISA, n.d.). This allowed migrants who had overstayed their visas to leave Japan voluntarily without detention and with the prohibited re-entry period reduced to just one year. Inadvertently, however, the transition was a consequence of a crackdown on visa overstayers announced by Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi in 2006. That year, immigration officials arrested a Filipino couple who had used forged passports to enter Japan in the early 1990s. The case caused a public outcry when, in 2009, the couple were deported to the Philippines and left their daughter, who had been born and raised in Japan, behind. Because only the couple's minor daughter was granted, by Justice Minister Eisuke Mori, special permission to stay, this raised human rights questions about forced child separation (Amnesty International 2009; Japan Times 2009).

However, the major impetus to enact the policy came after the 2010 forcible execution of one of 24,000 deportation orders issued that year, which resulted in the death of a Ghanaian national who had been a long-term undocumented resident. The case attracted wide attention in the national media, heightened public awareness, and triggered organized responses from Japan's human rights groups (Johnson Reference Johnson2014; Kawakami and McNeill Reference Kawakami and McNeill2011). Various migration NGOs, including the Asian People's Friendship Society and the Solidarity Network with Migrants Japan, ‘used the case to address the problem surrounding forced deportation’ in their governmental advocacy.Footnote 12 They lobbied Diet members and petitioned related ministries, including senior bureaucrats such as Shoko Sasaki, who later became the first commissioner of the newly established Immigration Services Agency. The efforts of Japan's civil society, contrary to the implications of the neoliberal view, were directly pitted against those of the state.

Moreover, the 2010 incident triggered lengthy legal battles. Sending a strong signal to the government, the Tokyo District Court ruled in March 2014 that immigration officers had subjected the deportee to excessive – ‘unfair and unlawful’ – use of force and were responsible for his death. The ruling was widely hailed as ‘a landmark because it was the first time that a court [in Japan] had ordered immigration officials to pay damages for the death of a foreigner due to mistreatment’ (Fackler Reference Fackler2014). At the same time, the influential Japan Federation of Bar Associations pressed the government to limit forcible removals to the ‘absolute minimum’ and make legislative changes that would protect the human rights of deportees.Footnote 13 In November 2014, it submitted a written opinion to the MOJ that urged the government, among other things, to specify in the law that ‘deportation enforced in a physical manner should be avoided to the extent possible’, and that the standards and methods of ‘conducting deportations should be set so as not to excessively restrict human rights’. The association demanded that in the case of ‘those who are averse to being sent back to their home country, the law should avoid the situation where such persons are subjected to immediate deportation, after the issuance of a written deportation order’, without being offered the means and time to reach external contacts or seek counsel. It stressed, furthermore, that Japan's ‘state should provide a detailed training programme regarding international human rights law and international human rights standards’ for officials ‘who may be required to restrict the physical freedom of persons in the deportation procedures’ (JFBA 2014). Although the initial legal ruling was reversed by the Tokyo High Court in January 2016 (Osaki Reference Osaki2016), the 2010 deportation and events that ensued set an important precedent and raised awareness in this area for large numbers of people in the government.

Consistent with the liberal logic, mounting legal proceedings and civil society pressures had lasting repercussions for the conduct of Japan's immigration apparatus. As a Justice Ministry official explained it to me, the implications of the deportee's death while in state custody prompted immigration authorities to ‘refrain [from] forcible deportation’. Indeed, in the aftermath of the incident, no foreigners were forcibly expelled for nearly three years (Asahi Shimbun 2018). As the official further explained, ‘the Japanese government can enforce unilateral deportation’, even if migrants take legal action against the immigration authorities, ‘but in reality it is difficult for the Japanese government to deport migrants if they sue in court from the point of view of human rights’. As such, according to the official, bureaucrats usually wait until a court case has been concluded and judgment on the person's residential status has been passed.Footnote 14

In that context, the Japanese authorities turned to assisted repatriation as ‘one method to make [unauthorized migrants] return home’. The policy targets those who disregard a deportation order and sue for its cancellation or apply instead for refugee status.Footnote 15 As I was told by the ministry official, since legal proceedings are lengthy and the verdict uncertain, immigration officials ‘select migrants who will possibly change their minds’ about staying in Japan and use ‘financial support to promote their voluntary return’.Footnote 16 In short, the efforts are aimed at ‘deportation evaders’ who seek to remain in Japan at any cost (MOJ 2019). Modelled on Europe's experience and implemented in cooperation with the IOM in 2013, the programme seeks to ‘persuade’ and ‘encourage’ them to leave (MOJ 2018a; see also MOJ 2013, 2018c). The liberal underpinnings of this border control initiative are apparent, in that it is carried out by the MOJ's upgraded Immigration Services Agency (formerly the Immigration Bureau) as the main stakeholder, in line with the IOM's goal of promoting migrants’ humane return and human rights.Footnote 17 The agency's Enforcement Division is in charge of the assisted repatriation of illegal residents, and, aided by the agency's Adjudication Division, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ International Safety and Security Cooperation Division oversees the voluntary return of victims of trafficking.Footnote 18 Although these post-arrival measures are still in their infancy, assisted repatriations have increased from year to year, exceeding 100 overall in 2017 (IOM 2018). This number is modest because, according to the immigration official I spoke with, most foreign migrants simply accept their deportation orders and return home through private means.Footnote 19

Paradoxically, as Japanese authorities seek to induce voluntary returns, the imperative of effective border control steers their actions in an illiberal direction. When their cautious stance on the forcible removal of irregular migrants became publicly known after Japan resumed unilateral deportations, many unauthorized residents, including rejected asylum claimants, refused to be expelled. As a result, in 2018 the MOJ issued a directive that permits the prolonged detention of visa overstayers. This has resulted in a sharp increase in the number of long-term detainees (Asahi Shimbun 2018; Kishitsu Reference Kishitsu2018) and led to incidents of death under detention (Mainichi Shimbun 2019). The practice came under fire from numerous NGOs, human rights advocacy networks, lawyers’ associations, churches, academics and journalists, who accused it of violating human rights and the dignity of irregular migrants (Asahi Shimbun 2019; SMJ 2019). In turn, this significantly heightened public ‘awareness of human rights issues at detention centers’ in Japan (Mainichi Shimbun 2019). In response to this criticism, a senior immigration official admitted that ‘the most effective method to decrease the number of long-term detainees is deportation’ (Asahi Shimbun 2018).

Like other liberal states, Japan has not ceased in its efforts to remove undocumented migrants unilaterally when deemed necessary (MOJ 2018b).Footnote 20 Indeed, given that 43% of deportation evaders have allegedly committed crimes in Japan, Shoko Sasaki, the country's top immigration executive, declared publicly that Japan is ‘obliged to deport’ them (cited in Fritz Reference Fritz2019). In this context, the most recent focus of civil society's advocacy is on the detention of unauthorized migrants – but, as the insider affirmed to me, in practice the issue of ‘detention and deportation cannot be separated’Footnote 21 (see also SMJ 2019). To sum up, the Japanese state's timid attempts at more liberal conduct have collided with the mundane, if not harsh, reality of immigration enforcement on the ground and, subsequently, with the promoters of more humane treatment of irregular foreign residents. This well illustrates the persistent inconsistencies in migration management in liberal democracies. Nonetheless, these dynamics offer revealing insights into the state's logic of assisted repatriation.

Conclusion

Contrary to the conventional view that associates assisted repatriation with neoliberal tactics, I argue that a liberal thread runs through this policy. This multifaceted phenomenon is better conceptualized as a subset of immigration control policies rooted in the growing commitment to migrant rights. Although assisted repatriation falls short of defusing all tensions in liberal theory and practice, conceptually, from the state's perspective, under more favourable conditions repatriation is more closely aligned with the values and institutions of a liberal democratic polity than the alternative: forcible management of unwanted migrants. It is this quality that has increased the policy's appeal for policymakers in liberal democracies worldwide, including Japan.

This study takes one step forward in identifying the conceptual underpinnings of assisted repatriation in liberal democracies without committing to an irrefutable causal relationship. Realities on the ground are often more complex than the principle of parsimony dictates, as evidenced by migrants’ complicated stories. Similarly, states’ decisions to implement assisted repatriation may involve many factors, including external pressures and pragmatic considerations. More research is needed to uncover the role of these determinants, and to that end I propose the following lines of inquiry. The first concerns the cross-national variation among liberal states in the application of this policy. For example, as reported by the IOM, the US does not use assisted repatriation, and the number in Canada has dropped from 2,000 in 2013 to zero. With border control increasingly politicized, this raises questions as to why some liberal democracies are more eager than others to employ state-induced returns, and why some of them are more reliant on the IOM. The second issue specifically concerns Japan. I have offered preliminary findings here, but it would be instructive to observe the expansion of the Japanese policy and establish conclusively its primary driver. Lastly, there remains an intriguing question regarding the use of liberal return schemes in authoritarian states. We can speculate that the growth of this phenomenon in the last decade can be attributed to global-institutionalist incentives or pressure from world opinion, but this issue warrants a separate inquiry.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 91st Canadian Political Science Association Annual Conference, 4 June 2019, University of British Columbia. The author thanks Isabelle Cote for her valuable feedback on the initial draft and Chuah Yong Li for his helpful research assistance. The author is also grateful to the four anonymous reviewers of this journal for their constructive comments and suggestions.