In an era of populism and extremism, promoting moderation and combating polarization in electoral politics has become increasingly urgent for established and developing democracies alike. Centripetal approaches to democratic development often advocate electoral reforms to foster political aggregation, multipolarity and moderation in societies divided by identity cleavages such as race, religion, language and region (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985, Reference Horowitz and Montville1991; Reilly Reference Reilly2001, Reference Reilly, Cordell and Wolff2016). Candidates who can attract widespread support alone or as part of broad-based multi-ethnic parties or coalitions are seen as the best way of avoiding the tendency towards outbidding and extremism inherent in polarized electoral politics and ethnically exclusive party systems (Rabushka and Shepsle Reference Rabushka and Shepsle1972).

While institutional strategies vary, a common centripetal aim is to incentivize politicians to seek and indeed require the votes of communities other than their own for their election and re-election. Such cross-ethnic vote-pooling stands in contrast to systems in which politicians can rely on merely the support of their own co-ethnics to secure victory. This matters for ethnic conflict: those who must appeal to a broad swathe of the electorate to win their seat are unlikely to alienate potential voters with mono-ethnic appeals, or to engage in sectarian rhetoric or policy proposals. Centrist and accommodative campaigns can be expected to lead to more centrist and accommodative government. Maintaining inter-ethnic harmony and avoiding ethnic polarization and outbidding thus starts at the ballot box.

Centripetalism is sometimes contrasted with consociational democracy, which prefers that voters support their own co-ethnic candidates and segmental parties, enabling leaders in power-sharing executives to negotiate directly on behalf of each group (Lijphart Reference Lijphart and Schreirer1990). But while consociationalism offers the foremost model of democratic peace-building in post-conflict situations, its preference for mono-ethnic parties built on ethnic block voting is a potential Achilles' heel. Numerous studies have found that ethnic voting harms democracy by turning elections into a quasi-census, thereby reducing electoral uncertainty, encouraging political patronage and inciting violence through ethnic outbidding, in which politicians from the same group compete via increasingly radical policies and rhetoric (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985; Houle Reference Houle2018; Rabushka and Shepsle Reference Rabushka and Shepsle1972). Democracy ideally works better with more competitive elections, cross-cutting cleavages and fluid ethnic identities (Chandra Reference Chandra2005; Lipset Reference Lipset1960).

Despite this, centripetal proposals for cross-ethnic voting have received only limited support. The idea of inducing cross-ethnic voting as a route to political and policy moderation is seen to suffer from a paucity of empirical cases and to rely on outlandish assumptions about the willingness of voters to cross the ethnic divide. This critique began with Arend Lijphart, who observed over a decade ago that centripetal ideas ‘do not seem to have sparked a great deal of assent or emulation’ (Lijphart Reference Lijphart2004: 99). Subsequent critiques focused not just on limited numbers of cases but also a claimed paucity of institutional levers: Brendan O'Leary, for instance, sees centripetalism as encapsulated in just ‘two approaches to electoral system design’, geographic distribution formula for presidents and alternative or ‘ranked-choice’ voting for parliaments (O'Leary Reference O'Leary, McEvoy and O'Leary2013: 19). Allison McCulloch, in a book-length comparative analysis, reflects a similar sentiment: ‘The universe of centripetal cases … is limited in scope’, making centripetalism ‘difficult to appraise because of an absence of cases that conform to its foundational design’ (McCulloch Reference McCulloch2014: 8, 30). Finally, all three critics see the majoritarian electoral systems favoured by some centripetalists as inherently hostile to minorities, advantaging the largest group and offering minorities merely the promise of influence rather than the kind of guaranteed representation afforded by proportional representation and consociational power-sharing.

Cross-ethnic voting

Much of the debate on centripetalism has focused on the utility of preferential electoral systems such as the alternative vote, which can encourage or at times require electors to express a preference for candidates from other ethnic groups (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985; Reilly Reference Reilly2001). Critics have expressed scepticism that voters in divided societies would be willing to cast a ballot, even as a secondary preference, for an ethnic rival (Coakley and Fraenkel Reference Coakley and Fraenkel2017; Lijphart Reference Lijphart2004; O'Leary Reference O'Leary, McEvoy and O'Leary2013). However, many other electoral systems can also promote cross-ethnic voting, and a burgeoning scholarly literature has documented the various ways in which leaders in multi-ethnic democracies under different electoral models attract voters across ethnic lines, ranging from cross-ethnic political and economic alliances to appeals based on their own or even their spouses’ multiple ethnic identities (Adida et al. Reference Adida, Combes, Lo and Verink2016). Studies of ethnic politics include numerous examples of politicians seeking and winning votes from groups beyond their own in situations of inter-ethnic war (Sri Lanka), rivalry (Nigeria), marginalization (Guyana), hierarchy (India) or polarity (Malaysia), often via cross-ethnic endorsements and pre-electoral coalitions (Arriola Reference Arriola2013; Chandra Reference Chandra2005; Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985; Posner Reference Posner2005).

Thus Malaysia for many years saw the Barisan Nasional, a ruling coalition dominated by ethnic Malays, engage in selective vote-pooling with the country's Chinese and Indian minorities, particularly in urban areas (Horowitz Reference Horowitz and Montville1991). Similarly, in Mauritius, despite a Hindu majority, communal parties have consistently been able to win elections by standing candidates from rival groups (Selway Reference Selway2015: 166–174). In recent Indonesian elections, ‘candidates avoided any negative appeals against particular ethnic groups. Moreover, it was common for candidates to visit, get endorsed by, and appeal to ethnic groups they did not belong to’ (Fox Reference Fox2018: 1202). Cross-ethnic voting has also been a mainstay of Indian elections, due to the historical dominance of the Congress Party as well as explicit strategies by smaller parties to build ties with non-core voters (Devasher Reference Devasher2019). In Kenya, Nigeria and Ghana, ‘since the return to multiparty politics across the region in the early 1990s, not only have incumbents sought re-election with the support of politicians from multiple groups, but cross-ethnic endorsements among opposition politicians have also occurred in over one-third of national elections; half of those alliances have resulted in executive alternation’ (Arriola et al. Reference Arriola, Choi and Gichohi2017). In Guyana and Sri Lanka, breakthrough 2015 presidential elections saw the winning candidate succeed in part due to endorsements from leaders of the minority Indo-Guyanese and Tamil communities, respectively.

It is true that in deeply divided societies, inter-ethnic appeals and compromise can be costly to parties who attempt them (Hulsey Reference Hulsey2010: 1140). But once the universe of cases is opened up to include less divided ‘plural’ societies, cross-ethnic voting becomes much less rare than critics contend, and in some cases almost routine. After all, most democracies are multi-ethnic, and cross-ethnic appeals are a relatively common electoral strategy in many of them. Particularly under plurality or majority electoral systems which constrain candidature, ‘catch-all’ campaigns are often fundamental for any party or candidate attempting to build a broad constituency and win government (Stojanović and Strijbis Reference Stojanović and Strijbis2019). As long as electorates are ethnically heterogeneous – for example, by virtue of their demarcation, or as a consequence of the office being chosen at a state-wide or nationwide level (such as for elected senators, governors or presidents) – then ‘cross-racial mobilization’ becomes a viable and sometimes essential campaign strategy (Alamillo and Collingwood Reference Alamillo and Collingwood2017). Once mobilized in this way, pan-ethnic coalitions become a more politically viable route to policy moderation than mono-ethnic appeals (Horowitz Reference Horowitz and Montville1991: 472).

To take a well-known recent example, Barack Obama's victories in the 2008 and 2012 US presidential elections were reliant on cross-racial appeals not just to white and black voters, but also (and most consequentially) to Latino voters. As someone both African-American and bi-racial, growing up in Hawaii and Indonesia, cross-racial appeals were a credible and in many ways essential electoral strategy for Obama. But it was his courting of the Latino vote – via campaign appeals and micro-targeting as well as Spanish-language websites and advertising – that delivered electoral victory. In 2012, for instance, ‘the margin Latinos provided to Obama exceeded the overall margin he won by, suggesting that if the Latino vote had not been mobilized, Obama would have lost’ (Collingwood et al. Reference Collingwood, Barreto and Garcia-Rios2014: 635). Following Hilary Clinton's failure in 2016, we are likely to see Democrats return to a cross-racial strategy for future presidential elections as demographic changes make cross-racial mobilization ‘the future of American politics’ (Collingwood Reference CollingwoodForthcoming).

Cross-voting can also be controversial. In Indonesia in 2016, the Chinese Christian governor of Jakarta, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (better known as Ahok) was accused of blasphemy after saying that people should not vote for a candidate based on religious beliefs, and that Muslims could be represented by non-Muslims. An edited video of these remarks was used to suggest Ahok was insulting the Qu'ran, triggering violent street protests and his arrest and imprisonment. Cross-ethnic voting has also proved controversial at Bosnia's tripartite presidential elections in which voters choose between a Bosniak, Croat and Serb representative. Croat candidate Zeljko Komšić has repeatedly found success by running under a multi-ethnic party label and appealing not just to Croat but also to Bosniak voters, fuelling debate about the legitimacy of such ‘cross-over voting’, and whether Komšić-supporting Bosniaks were voting strategically or simply expressing a preference for a nation-building moderate (Kasapović Reference Kasapović2016).

In sum, strategies of inter-ethnic vote-seeking, cross-racial mobilization and cross-ethnic voting are far more common than is acknowledged in some of the aforementioned critiques of centripetalism. Likewise, as this article will show, there are numerous electoral innovations in multi-ethnic states which require or encourage politicians to seek votes from a range of social groups as part of their quest for election and re-election. Far from being rare, institutional incentives for cross-ethnic voting actually turn out to be surprisingly common. This is important, as centripetal theory suggests that by ‘making moderation pay’, such cross-ethnic incentives should lead to improved inter-ethnic relations and more accommodative policy offerings (Horowitz Reference Horowitz and Montville1991).

Strong, moderate, weak and anti-centripetalism

Given the ongoing debate on institutional design in ethnically divided societies, it is important to expand and also refine the scope of cases under which centripetal electoral competition can occur. One way to do this is to focus on the extent to which cross-ethnic voting is encouraged and enabled via the electoral system. The following discussion and accompanying tables present an initial classification of such cases, based around a three-way division between strong, moderate and weak centripetalism. Ideally, this would be buttressed by behavioural data showing the extent to which such cross-ethnic voting occurs in practice. For now, however, I focus on structural aspects of the electoral system only.

Strong centripetalism requires three things of an electoral system: encouragement for multi-ethnic political parties, incentives for reciprocal vote-pooling between ethnic groups, and the avoidance of formalized or corporate criteria of ethnic identity. Indonesia (discussed in the case study below) is probably the best example of such a system amongst contemporary democracies. There, a panoply of representative institutions encompassing the presidency, parliament and political parties feature mutually reinforcing electoral incentives for multi-ethnic politics. Kenya and Nigeria have also used some of these devices, such as cross-national party laws and distribution requirements, with less success, while similar strongly centripetal proposals such as Uganda's ‘constituency pooling’ model have yet to be implemented (Bogaards Reference Bogaards2003). Other forms of strong centripetalism feature exhaustive preferential voting with a majority threshold, such as the alternative vote with compulsory allocation of preferences. This is the system used for most elections in Australia – the most ethnically diverse society in the OECD on some measures, and one of the few Western democracies to avoid the upsurge of populist politics in recent years, but an unlikely model for divided societies (Reilly Reference Reilly2018).

By contrast, my second category of moderate centripetalism – cases which encourage but do not necessarily require cross-ethnic voting – contains a larger and more diverse range of recent experiments which may offer broader potential as a model for emulation. Moderately centripetal systems display some but not all of the criteria by which we assessed strong centripetalism. For instance, they may encourage vote-pooling and multi-ethnic parties, but breach the fluidity criteria by formally specifying group identity, as in Burundi's party law, which requires ethnically balanced lists. Or they may retain group fluidity and vote-pooling but do nothing to develop multi-ethnic parties, as in Papua New Guinea's use of ‘limited’ preferential voting. Other kinds of moderate centripetalism are nested within broader consociational settlements, as in Northern Ireland's single transferable vote. In all cases, however, the cross-voting incentives which do exist are real and consequential for ethnic politics.

My final category, weak centripetalism, typically features more tokenistic efforts at promoting cross-ethnic voting and multi-ethnic parties in quasi-democratic or electoral authoritarian regimes. While this category is also very broad, a common pattern is that in most cases the cross-ethnic incentives that do exist in the electoral system are overwhelmed by broader realities of the regime type in which electoral competition takes place, be it corporate confessionalism (Lebanon), single-party dominance (Singapore) or clientelistic familial patronage (the Philippines). In each of these cases, part of the electoral system creates genuine cross-voting opportunities, but these are too limited to impact substantively on broader ethnic relations. A subcategory includes what Matthijs Bogaards (Reference Bogaards2019) calls ‘uni-directional vote-pooling’, in which minorities are chosen on a cross-ethnic basis by all voters but without the reciprocity inherent in more genuine vote-pooling models.

The following index discusses each of these classifications in turn, including instances of each type cited in the literature and an extended case study of one or more key exemplars. There is also a final residual category, non-centripetal systems, which preclude cross-ethnic voting altogether by formalizing ethnic criteria and restricting both voting and candidature to the same group. These are typically seats reserved for ethnic minorities, particularly indigenous groups, as in New Zealand's Maori reserved seats or Taiwan's reservations for aboriginal voters.

Strong centripetalism

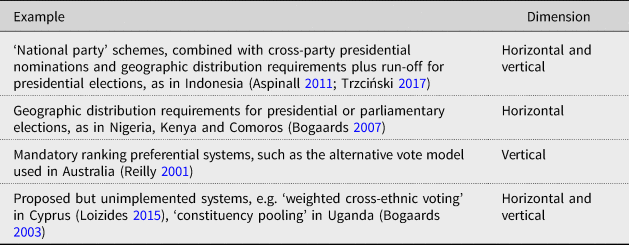

As noted above, cross-ethnic voting is not unusual, and indeed is a common aspect of elections in most plural societies, particularly those in which electorates are large and heterogeneous and candidature is restrained – as in many majoritarian democracies. However, some cases go further and make cross-ethnic voting not just an appealing political strategy but a mandatory aspect of electoral competition. These strongly centripetal systems tend to have both ‘horizontal’ and ‘vertical’ dimensions (see Table 1). Horizontally, aggregation can take place across a state's territorial spread, in the form of nationalized political parties, ethno-regional vote distribution rules or requirements for concurrent pluralities in multiple districts. Alternatively, cross-ethnic voting can also be achieved vertically within single-member electorates, via preferential balloting, majority run-offs or at-large plurality voting. Some cases, such as Indonesia, combine both horizontal and vertical dimensions, providing perhaps the most comprehensive assortment of centripetal incentives amongst contemporary democracies, as discussed in the case study below.

Table 1. Cases of Strong Centripetalism

Case study: Indonesia

Indonesia's political evolution since the fall of the Suharto regime and its return to democracy in 1999 offers one of the most comprehensive examples of centripetalism as a strategy of institutional design and represents arguably the most significant case of multi-ethnic democratization since the end of the Cold War. Its institutional architecture features a plethora of democratically elected offices at the national and subnational level which vary in details but adhere to an overarching pan-ethnic, cross-voting stratagem designed to promote a national, pan-ethnic identity across the vast Indonesian archipelago stretching over 3,000 miles and 17,000 islands. While aspects of Indonesian democracy such as the ongoing presence of religious parties and proportional voting are closer to the consociational model, many of Indonesia's electoral institutions are explicitly centripetal (Trzciński Reference Trzciński2017). These include an executive president both nominated and elected on an explicitly aggregative basis; cross-national organizational requirements for political parties which make most locally based parties unviable; a territorial structure which proliferates and in some cases divides potential ethnic powerbases; and semi-majority run-off electoral laws for regional governors.

Reflecting the country's founding precepts as a multi-ethnic and multireligious nation, this package of centripetal institutions was adopted at the height of Indonesia's democratic transition (1998–2001), when ‘politicization of ethnicity occurred with sometimes startling speed and ferocity’ (Aspinall Reference Aspinall2011: 293). Fears of ethno-religious mobilization and secessionism revived widespread elite concerns – present as long as Indonesia has existed as a nation – about separatism, centre–periphery relations, and tensions within Islam. Since then, Indonesia has enjoyed over two decades of continuous democracy and large-scale ethnic peace. How was this achieved?

The first democratically chosen presidents, Abdurrahman Wahid (1999–2001) and Megawati Sukarnoputri (2001–4), both saw ethno-regional political parties as a particular danger which would ‘tear at the fabric of the nation and lead to secession’ (Hillman Reference Hillman2012: 424). These fears were based on widely held readings of Indonesian history, particularly the failed democratic experience of the 1950s, which featured political violence, separatism, deadlock and fragmentation. In response, a package of centripetal changes was adopted via a strategy of incremental institutional reform (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2013). Parties were required to demonstrate a cross-regional organizational network and achieve a minimal level of support to compete at elections, by having branches spread across most provinces, as well as the districts or municipalities within these provinces – making minority inclusion a function of political party candidature. These rules have been progressively tightened at each election, to the point where today parties must have chapters and permanent offices in all 34 provinces, and at least 75% of the municipalities and 50% of the subdistricts within them. This requires parties to open and maintain thousands of branches across the country.Footnote 1 Over this same period, the bar for election was also raised by reducing overall district magnitude to between 3 and 10 seats per district – increasing the effective electoral threshold for a seat to almost 20% – and a national threshold (now 4%) introduced to limit splinter parties.

Presidential elections follow a similar centripetal path. When direct presidential elections were introduced in 2004 it was decided that coalitions of these cross-national parties should control the nomination of candidates for Indonesia's presidency, bridging ethnic and regional divisions and differing approaches to the role of Islam in politics. The election itself requires successful candidates to demonstrate both vertical and horizontal legitimacy by attaining both a nationwide majority and at least 20% of the vote in over half of Indonesia's 34 provinces to avoid a run-off election. These constitutionally enshrined provisions, as with the party laws, aim to ensure that any successful candidate will command broad support across a large and diverse country: ‘While a majority winner will almost certainly achieve this, the requirement prevents a ticket whose support is solid in highly populated Java and minimal elsewhere from winning an election in the first round’ (Reynolds et al. Reference Reynolds, Reilly and Ellis2005: 69).

Although often criticized for being a block on competitors and deterrent to new entrants, in terms of democratic stability, these rules have succeeded to a degree which seemed unlikely when they were introduced. By making all parties outside Aceh putatively national in scope, Indonesia's party system has ‘proved remarkably adept at encouraging cross-ethnic bargaining and in minimizing the role of ethnicity in politics’ (Aspinall Reference Aspinall2011: 311).Footnote 2 All winning presidents to date have easily surmounted the geographic distribution requirement, while the run-off provision has only been consequential in the first direct presidential election in 2004, which featured a lower entry threshold for candidates to nominate. In 2009, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono won a landslide first round victory with 61% of the vote. Five years later, in 2014, Joko Widodo won a first-round victory with 53%, a feat he repeated with a similar majority in 2019.

While attributing direct causality is difficult, it is also notable that the more moderate presidential candidate has triumphed over sometimes much more extreme opponents in every election to date, greatly aiding the consolidation of Indonesian democracy. As pragmatic, moderate Muslims, Yudhoyono and Widodo each campaigned on policy rather than identity lines, and easily gained the broad support required for their election victory. Yudhoyono was dubbed the ‘moderating president’ (Aspinall et al. Reference Aspinall, Mietzner, Tomsa, Aspinall, Mietzner and Tomsa2015), while Widodo's focus on outer-island development saw him dominate the votes from these same regions, as well as winning almost all religious minority voters – objectives promoted by the centripetal electoral laws. As a result, both presidents were able to defeat hard-line former generals Wiranto (who opposed Yudhoyono in 2009) and Probowo (who ran against Widodo in 2014 and 2019), either of whom might have won under a different electoral system.

In sum, Indonesia's centripetal political engineering appears to have helped stabilize democracy and avert a widely predicted descent into ethnic conflict. As one country expert observed:

How is it that Indonesia has defied so many predictions early in its transition and become a country where ethnicity seems to have such limited impact on political life? … The first [answer], and most relevant for comparative studies of ethnic politics, is institutional design … A suite of institutional reforms implemented relatively early in Indonesia's democratic transition conspired to undercut the role that ethnicity would play in national political life and to tame the ethnic passions that had been so powerfully unleashed. (Aspinall Reference Aspinall2011: 290)

Indonesia thus stands as a (neglected) example of what David Lublin (Reference Lublin2014) calls ‘electoral rules designed to limit ethnoregional parties’, albeit mostly via political party rules and candidature limitations rather than electoral systems per se. More importantly, for the purposes of this article, it offers a range of incentives for cross-ethnic voting at multiple levels of government – gubernatorial, legislative and presidential – making it perhaps the clearest example of centripetal political engineering in the democratic world today.

Moderate centripetalism

An alternative centripetal approach is to mandate inclusion of all significant ethnic groups, both minorities and majorities alike, directly on party lists for elections. If candidates from all salient groups are included in similar proportions within broader pan-ethnic parties, then it follows that all voters, regardless of their ethnicity, must choose on a basis other than co-ethnic identification when casting their vote. Undermining ethnic voting in this way is not ideal as it involves a formal assignation of ethnic identity, but it can also de-politicize ethnic cleavages and, depending on the specific design adopted, encourage inter-ethnic moderation and cross-ethnic dialogue as well. The key centripetal insight – that voters will, if compelled to vote for members of communities other than their own, tend to promote moderates and reject hardliners and extremists from other groups – is thus particularly relevant to such schemes.

The specific design options which can encourage or even compel such cross-ethnic voting include the imposition of ethnic quotas within party lists for most (Burundi) or a sizeable minority (Nepal) of elected seats; balancing the composition of the legislature by appointing ‘best losers’ among designated ethnic candidates from those lists (e.g. Burundi again, as well as Mauritius); or nesting ethnic quotas within gender quota systems (Burundi, Afghanistan and Djibouti).Footnote 3 Such different approaches each require the electorate to choose between competing parties offering different policies but with the same balance of ethnicities on their ticket. Such centripetal characteristics are, however, undercut by the way such systems enshrine and formalize group rights and ethnic identity in law, as illustrated in the following case studies of Burundi and Nepal.Footnote 4

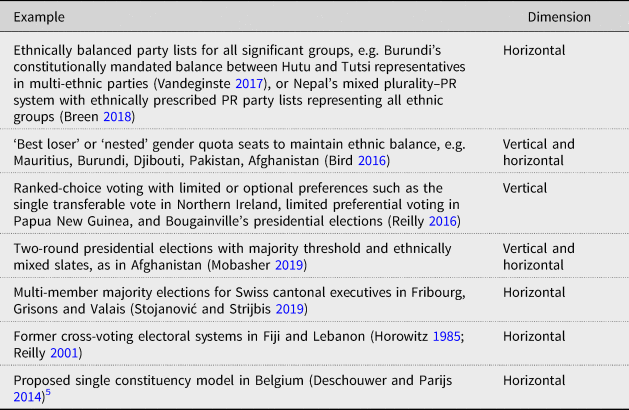

These and forms of moderate centripetalism discussed in the scholarly literature are illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2. Cases of Moderate Centripetalism

Case studies: Burundi and Nepal

Post-conflict constitutional settlements in Burundi and Nepal are good examples of what Stefan Wolff (Reference Wolff, Brown and Langer2012) has called ‘complex power sharing’, whereby multiple institutional approaches are combined within a framework of territorial self-governance. Both settlements were designed ostensibly to be more consociational than centripetal, with ethnic groups forming the building blocks of parliament. However, both states have constitutionally enshrined centripetalism by combining ethnic quotas with multi-ethnic political parties, making cross-ethnic voting central to both electoral and parliamentary politics and offering the promise of bridge-building across group distinctions both within parliament and in the electorate as a whole.

Despite recent setbacks, Burundi has been justly celebrated as a successful example of constitutional engineering (Reyntjens Reference Reyntjens and Kuperman2015; Vandeginste Reference Vandeginste, McCulloch and McGarry2017). Following the failure of repeated attempts to democratize a minority-dominated government and military, culminating in the 1993 civil war and genocide, the 2000 Arusha peace accords introduced a wide-ranging reform package aimed at managing relations between the Hutu majority and Tutsi minority. As part of this settlement, ethnic ratios in parliament were constitutionally fixed and multi-ethnic parties were prescribed in law. While the reality of ethnicity as the core cleavage in Burundi society was thus acknowledged, it was also undermined by constitutionally mandated cross-ethnic voting both for general elections and also within the parliament.

The key cross-voting mechanism is contained in Burundi's closed list system of proportional representation, which includes a constitutional requirement that of every three candidates on a party list, one must be of an alternate ethnicity than the two others. In practice, this means that predominantly Hutu parties must include one Tutsi candidate at every third position on their list, and vice versa for predominantly Tutsi parties. Given the differences in size between the two communities, this makes the likely outcome of a general election more or less in line with the 60% Hutu/40% Tutsi ratio for parliamentary representation imposed in the 2005 constitution. Corrections to any deviations from this ratio are made by the Electoral Commission co-opting losing candidates to ensure that overall ethnic balance is maintained. (A third group, the Twa, also have guaranteed representation, with three co-opted members in both chambers of parliament).

The result of this structure is that while voters can choose between more predominantly Tutsi or Hutu parties, they cannot choose between ethnically exclusive parties. This pushes voters and candidates alike to make political judgements and alignments on policy, personal ties or some other basis than ethnic ratios, which are effectively fixed. As one country expert notes, ‘this system adds an important centripetal dimension to ethnic power-sharing in Burundi. Parties need to attract candidates and voters across the ethnic divide and party officials are automatically involved in inter-ethnic exchange and dialogue’ (Vandeginste Reference Vandeginste, McCulloch and McGarry2017: 178). While the requirement for multi-ethnic electoral lists was a key point of contestation during the transition and the constitution-building process, it appears to have become accepted and fostered a depoliticization of ethnicity in Burundian politics (Raffoul Reference Raffoul2020). The government has recently sought to move away from many of the power-sharing provisions agreed at Arusha with a new constitution, but has not altered the voting rules.

A similar approach to institutional design can be found in Nepal's 2006 peace deal and subsequent constitutional reforms. In part due to its extraordinary terrain, Nepal has over 100 ethnic groups – none of them a majority – spread across its southern lowlands and throughout its mountain valleys. A 10-year guerrilla war waged by Maoists and other left-wing parties for a people's republic intersected with the gruesome internecine 2001 murder of most of the royal family, creating the possibility of a transition to a more inclusive and democratic multiparty republic in Nepal than its monarchical predecessors. These earlier governments had been dominated by the hill elite groups such as the Brahmins and Chhetris, despite such groups making up less than a third of the overall population, with low-caste and marginalized groups – who formed the support base for the Maoist armed struggle – traditionally receiving almost no representation despite comprising over a fifth of the population.

This changed in 2008 when, under the terms of a peace deal and with the assistance of the United Nations and other international organizations, a Constituent Assembly was elected representing the full diversity of Nepalese society, with over half the body reserved for minority, lower-caste or backwards regions and at least a third women, another major change from the past (Vollan Reference Vollan2011). To achieve this, most seats were elected on a nationwide basis by proportional representation, with parties compelled to produce party lists which reflected the communal composition of Nepalese society. However, this highly inclusive model also made reaching agreement on a new constitution exceptionally difficult. After multiple extensions the Assembly was dissolved in May 2012, ending four years of drafting without an actual draft constitution (Reilly Reference Reilly2014).

In the end, it was not until November 2015 that a final constitution was adopted. Taking advantage of the chaos unleashed by an earthquake that had devastated parts of Kathmandu and other population centres earlier that year, the ruling parties diluted some of the communalism of previous drafts. Demands for identity-based provinces were rejected, and the major parties sought to wind back what many saw as a donor-driven agenda for minority inclusion in parliament (Ghale Reference Ghale, Thapa and Ramsbotham2017). However, the electoral laws continue to mandate the representation of both privileged as well as underprivileged groups, including the exact proportion of seats each party list must allocate to six ‘inclusion groups’ specified in the constitution: Dalit (13.8%), Adivasi Janajati (28.7%), Khas Arya (31.2%), Madeshi (15.3%), Tharu (6.6%) and Muslim (4.4%). These aim to collectively encompass every major ethnic, religious or caste group in Nepal, not just those that are considered underrepresented. For instance, ‘Khas Arya’, the largest category, includes Brahmin and other sociopolitically dominant groups. There are also quotas of candidates from minorities and backward regions, and for persons with disabilities, while 50% of the elected representatives within each group must be women. As a consequence, parties must now be broadly representative, in sharp contrast to the past, and voters must make their choice on a basis other than ethnicity for the party list aspect of elections at least, now comprising 110 of the 275 seats.

While relatively successful in terms of containing conflict and maintaining democracy, such a rigid allocation also creates major issues in how to verify and accept that candidates are indeed members of one of the allocated groups – that they are who they say they are. Rarely given much thought by scholars, in practice this aspect of formalized group quotas can be almost comically difficult: some Nepalese parties chose all-male candidate lists, despite the gender-balance requirement, while others claimed that their designated minority candidates actually hailed from multiple different groups, and should thus be counted more than once in determining a party's compliance with the law – creating more room on the list for non-minorities. Some able-bodied candidates attempted to pass themselves off as disabled, and so on (Pokharel and Rana Reference Pokharel and Rana2013).

Like Burundi, Nepal's success in addressing core pathologies of ethnic inclusion and exclusion thus entailed a formalization of identity which has costs as well as benefits. While offering a distinctive route towards broad-based representation, mandating cross-ethnic voting via group quotas can also be fraught with normative and operational problems. An under-appreciated element of such arrangements is the transaction costs and administrative burdens they entail, transferring decisions on identity claims to electoral management bodies rather than letting these be decided through the political process. These costs tend to be overlooked in the academic literature, where scholars are usually more interested in explaining an institution's origins or impacts than in examining how it can be administered (Reilly Reference Reilly2014).

Other kinds of electoral system design feature vertical rather than horizontal approaches to cross-ethnic voting. One example is the use of the limited preferential vote (LPV) in Papua New Guinea, which requires voters to express three preferences between candidates, rather than a single ordinal choice, with these rankings used to calculate the most broadly supported candidate if no one wins an absolute majority of the vote. A similar system encouraged cooperative campaigning behaviour in the country's pre-independence period (Reilly Reference Reilly1997), encouraging the system's adoption prior to the 2007 elections. More accommodative campaign patterns and reduction in election violence were repeated in the 2007 and 2012 elections, prompting the neighbouring Solomon Islands also to consider adopting LPV for future elections (Brent Reference Brent2017). Other variants of preferential voting in the Pacific islands include the reverse Borda count employed in Nauru and Fiji's brief experience with a ‘ticket vote’, often cited by critics of the model (Coakley and Fraenkel Reference Coakley and Fraenkel2017).

Elections in Papua New Guinea's autonomous island province of Bougainville (which voted for independence at a referendum in late 2019) have taken this model a step further, mixing both sectoral and preferential vote-pooling. Bougainville's autonomous elections since 2008 have included three seats reserved for ex-combatants and another three for women, all elected on a cross-communal basis. Although somewhat tokenistic, the fact that sectoral minorities are elected by a cross-section of voters, and require a majority of votes in the count to win their seat, is another centripetal measure which also serves to politicize multiple dimensions of identity and encourage fluidity. The preferential system used to choose the island's president has also encouraged a breadth of cross-island support, assisting the relatively moderate leader John Momis to triumph over separatists in 2010 and again in 2015 (Kolova Reference Kolova2016).

Ranked-choice voting systems have been found to have moderating influences in established democracies such as Australia and more recently the US (Reilly Reference Reilly2018), where the combination of a two-party system and single-member districts induces competing candidates to seek support from undecided voters in the centre of the political spectrum, thereby privileging political moderation over ideological partisanship. The first preferential vote count used to elect members of the US Congress, at the 2018 mid-term elections in Maine, saw a polarizing Republican achieve a narrow first-round plurality but lose the election after secondary preferences from independent voters were counted (Fried and Glover Reference Fried and Glover2018). Whether this kind of centralizing voter movement can occur under ranked-choice voting in deeply divided societies has been an ongoing debate within the scholarly literature (Coakley and Fraenkel Reference Coakley and Fraenkel2017; McCulloch Reference McCulloch2014).

Following this same logic, two-round run-off systems can also have centripetal effects for both voters and candidates (Sartori Reference Sartori1997). Because such elections create incentives for diverse interests to coalesce behind qualifying candidates in the second round, moderate candidates who have more coalitional appeal than their extremist counterparts are advantaged. André Blais and co-authors (Reference Blais, Laslier, Laurent, Sauger and Van der Straeten2007), after arranging several experimental elections, concluded that extremist candidates have a 0% chance of winning under majority run-off. However, while run-offs can be instrumental to developing trans-ethnic coalitions and governments, these are often more coalitions of convenience, in Donald Horowitz's (Reference Horowitz1985: 366–368) phrase, than longer-term commitments. For this very reason, presidential run-offs in ethnically divided societies often feature additional coalitional incentives, such as Afghanistan's dual vice-presidential model which encourages tri-ethnic tickets to appeal across the country's main ethnic groups, or the kind of presidential nomination rules found in Indonesia and elsewhere which require intending candidates to assemble sizeable pre-electoral coalitions (Mobasher Reference Mobasher and Ratuva2019).

Weak centripetalism

A third and less successful approach to encouraging cross-ethnic voting could be called weak or quasi-centripetalism (see Table 3). Rather than attempting to subvert ethnic mobilization, as in Indonesia, or depoliticize it by representing a country's entire identity spectrum, as in Burundi and Nepal, quasi-centripetal approaches focus on guaranteeing representation to specific ethnic minorities within broader majority-dominated bodies. Electors in Singapore's multi-member group representation constituencies (GRCs), for instance, cast a block vote for a team of four to six candidates, at least one of whom must be an ethnic minority – an arrangement which necessitates a limited degree of cross-ethnic voting, as voters have no option but to choose between competing candidate lists. Three-fifths of GRCs must elect at least one Malay candidate, with an Indian or ‘other’ minority in the remaining two-fifths. Introduced by the long-governing People's Action Party in order to sandbag their parliamentary majority (as the plurality party wins every GRC seat), these rules saw the election of 16 minority representatives in the 89-seat parliament at the most recent election, based on centripetal ambitions ‘to minimize candidate-based voting on ethnicity, gender or other traits … this prevents the politicization of local or ethnic issues. To be electable, parties have to be inclusive, and focus on crosscutting issues to appeal to the wide-spectrum of voters in the multi-member constituencies’ (Tan Reference Tan2013: 635).

Table 3. Examples of Weak Centripetalism (Limited Cross-ethnic Voting)

The Philippines’ party list system, introduced in the 1987 constitution as a way of increasing minority and sectoral representation in Congress, also contains limited cross-ethnic incentives. Comprising up to one-fifth of all lower house seats, these national list seats were originally reserved for ‘marginalized groups’ such as youth, labour, the urban poor, farmers, fishermen and women, with any group receiving at least 2% of the vote winning a seat, and each group limited to a maximum of three seats. In 2013, however, eligibility was expanded to include parties not organized along sectoral group lines but which could nonetheless claim ‘a track record in representing the marginalized and underrepresented sectors’ (Torres-Pilapil Reference Torres-Pilapil2015: 86). Again, as these parties are chosen by all voters nationwide, a limited degree of cross-communal voting is inherent in this approach to representing marginalized interests. At the same time, ‘it has also partially ghettoized those interests’ (Hicken Reference Hicken, Slater, Kuhonta and Vu2008: 95), with mainstream politicians increasingly colonizing the party list and using it as an alternative route to enter Congress.

Other examples include the ‘geometric mean’ system used to determine who wins the seat reserved for the French-speaking minority in the Swiss canton of Berne, which provides a degree of cross-ethnic voting but also encourages candidates to focus more on their own ethnic group, as well as the range of ‘unidirectional vote-pooling’ mechanisms discussed below.

Case study: uni-directional vote-pooling

In a final and arguably least effective quasi-centripetal category, representatives of minority communities need to appeal cross-ethnically for votes, but without an equivalent incentive for ethnic majorities to appeal to minorities (Bogaards Reference Bogaards2019). Examples include Lebanon's reformed electoral system, Jordan's reserved seats for Christian, Chechens and Circassian minorities,Footnote 7 and even, some would argue, the Croat seats in Bosnia's tripartite presidency mentioned earlier. Needing to appeal to the mass of the electorate presents particular challenges for minority candidates whose legitimacy depends on their ability to be a voice for their own community. If this link is diluted, minority representatives can be seen as at best inauthentic representatives, and at worse as stooges or sell-outs to the majority.

The 2017 revision of Lebanon's electoral system, which allocates all seats in advance to specific ‘confessional groups’ from the Muslim and Christian communities, is a case in point. Previously, with every voter able to vote for all seats in a district, candidates from smaller confessions would often be elected on the votes of other communities. The constitutional over-representation of Christians made this a particular issue for their minority Orthodox confessions, many of whom were elected predominantly by Muslim voters, so a new proportional system was adopted to make it more likely that parliamentarians be elected by their own co-religionists, rather than voters from different sects. Unsurprisingly, this is also an effect of rewarding candidates who cater to the concerns of their own religious communities rather than the broader electorate. However, a corresponding shift to printed ballot papers in which cross-sectarian party slates are presented means that Lebanon's new proportional system, like its formerly majoritarian variant, continues to encourage if not require a degree of cross-sectarian vote-pooling.Footnote 8

India's long experience with reserved seats for so-called ‘scheduled castes and tribes’ offers some insights into the authenticity issue. These date to the colonial period, when ‘separate electorates’ were reserved for specific communities such as Muslims, and elected solely by members of that specific community – thus, only Muslims could vote for Muslim candidates in the reserved Muslim constituencies. This shifted after independence, when seats reserved specifically for religious minorities were abolished. Today, all electors vote in seats designated for specific groups, such as those for officially scheduled castes (basically, the former ‘untouchables’) and indigenous ‘tribes’ – making cross-ethnic voting an important aspect of these elections, although this applies more to scheduled castes (who are widely spread and thus do not form a majority in any electorate) than scheduled tribes (who concentrate in peripheral regions and thus form a majority in many reserved electorates). While some have claimed India as an unlikely case of consociationalism (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1996), the extent of vote-pooling required in Indian scheduled caste elections clearly manifests centripetal properties. Whether this is normatively desirable for the representation of structurally under-privileged groups is another question: in needing to appeal to all electors, scheduled caste politicians are frequently accused of being unresponsive to their core community or of being token representatives (Jensenius Reference Jensenius2015b).

Will Kymlicka (Reference Kymlicka1995) argues that minority representatives chosen directly by their own minority is normatively superior to elections by an open and unconstrained voting public, as the need to appeal only to voters of the same minority creates a higher level of substantive representation. Empirical studies have confirmed that indigenous minorities at least are indeed happier with this kind of arrangement (Kroeber Reference Kroeber2017). This distinction also helps to clarify the limits of centripetalism. Particularly for indigenous communities, the legitimacy accorded to self-selection by a mono-ethnic electorate is superior to a model which trades off authenticity against breadth of voter representation. Such non-centripetal cases in which only members of the community itself can vote for their representatives include the seven Maori seats in New Zealand, the six Indigenous seats in Taiwan, the eight national minority seats in Croatia, and solitary seats for the Italian and Hungarian communities in Slovenia, each of which restrict elections to an ethnic subset of voters, using designations on the electoral roll.Footnote 9

Conclusion

Most analyses of electoral systems and ethnic representation focus on questions of proportionality (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1994) or how different electoral systems facilitate the ‘ethnification’ of politics (Huber Reference Huber2012). This article has taken a different approach, examining schemes which facilitate the inclusion of minorities (and in some cases, majorities as well) via cross-ethnic voting, and evaluating these according to how much vote-pooling ensues, from most (those requiring cross-ethnic vote-pooling) to least (those which preclude cross-ethnic voting entirely). In offering some much-needed conceptual refinement to discussions of centripetal institutions, this classification also expands the universe of cases which can be considered at least partly centripetal, such as those which make it mandatory for parties to present multi-ethnic candidate lists including all major groups, not just minorities, to the electorate. It also highlights the drawbacks inherent in such systems’ formalization of identity, which undermines broader centripetal goals of de-emphasising ethnic allegiances and allowing cross-cutting identities to emerge.

The distinction between ‘horizontal’ and ‘vertical’ centripetalism is another theoretical advance introduced in this article. Cases like Indonesia, Burundi and Nepal elect their party list representatives by proportional representation at a national level, requiring horizontal aggregation and campaign strategies. The same applies to the single transferable vote in Northern Ireland, although with much smaller districts. By contrast, in single-member contests, up to and including presidential elections, cross-ethnic voting occurs vertically – either through gradations of choice expressed for non co-ethnics under preferential voting; constrained candidature or coalition candidate balancing across heterogeneous plurality districts; or two-round run-offs widely used for presidential and gubernatorial elections. When both a president and vice-president are elected on one common slate, geographic balancing between presidential and vice-presidential candidates drawn from different regions offers the potential for combining this vertical model with a degree of horizontal vote-pooling as well. However, the utility of all of these models is greatly dependent on the ethnic demography of the electorate.

Less effective approaches include formal legal requirements to place ethnic minorities on party lists (rather than representatives of all relevant groups, as in Burundi and Nepal). Tokenism is a problem with many of these quasi-centripetal reforms. Singapore's GRCs are an example: because all parties must include minorities on their candidate lists, and everybody votes for all candidates, a limited degree of cross-ethnic voting is at one level inevitable. However, these and similar group-based reforms recently enacted for presidential elections (which reserve the ostensibly non-executive office for a Chinese, Malay or Indian on a rotating basis) are seen by many Singaporeans as compromising meritocracy through de facto affirmative action (Rodan Reference Rodan2018). The same critique could be applied to seat reservations for sectoral rather than minority ethnic representatives elected by such cross-voting systems, as is the case in the Philippines, whereby parties can claim a track record in representing ‘marginalized groups’, even if the representatives in question hail from elite families and privileged backgrounds (Torres-Pilapil Reference Torres-Pilapil2015).

A similar critique applies to the cases of scheduled caste elections in India and other forms of ‘uni-directional vote-pooling’ discussed earlier, which require minority candidates to appeal to the majority without an equivalent incentive for ethnic majorities to appeal to minorities. If seen as being elected predominantly by rival groups, representatives of all of these minority communities can suffer the potentially devastating critique of being labelled inauthentic representatives, as has happened to some Christian representatives in Lebanon. Even without this critique, the evidence from India, the longest-running example, suggests that simply reserving seats for underprivileged minorities has little if any substantive impact on their well-being (Jensenius Reference Jensenius2015a).

In sum, whether representatives are elected by all voters, or only a subset of co-ethnic voters, is a threshold issue not just for inter-ethnic relations but also in determining the impact of centripetal electoral reforms. This distinction also enables the construction of an alternative typology of electoral systems to more familiar indexes which rank electoral systems in terms of their proportionality (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1994) or their propensity to encourage a personal vote (Carey and Shugart Reference Carey and Shugart1995). The key to the various centripetal schemes discussed in this article is that even when offices are designated for specified minorities, they are chosen by all electors – members of the minority group as well as others – thus making some degree of cross-ethnic voting inevitable. Under such a typology, therefore, the key issue is not the proportionality of the system or the ability to vote for candidates versus parties, but rather how ethnically broad is the ‘selectorate’ (Bueno de Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno de Mesquita, Smith, Siverson and Morrow2003) – the group of voters who choose the representatives in question.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the anonymous reviewers whose suggestions greatly strengthened this piece.