I. Introduction

Twenty years after the publication of ‘International Norm Dynamics and Political Change’, Finnemore and Sikkink’s norms life cycle model (1998) continues to be a mandatory point of reference for theoretical (McKeown Reference McKeown2009, Bloomfield Reference Bloomfield2016; Wylie Reference Wylie2016; Nuñez-Mietz and García Iommi Reference Nuñez-Mietz and García Iommi2017) and empirical (Bailey Reference Bailey2008, Segerlund Reference Segerlund2010; Fisk and Ramos Reference Fisk and Ramos2014; Davies et al. Reference Davies, Kamradt-Scott and Rushton2015; Jose Reference Jose2016) scholarship on norm change. Pioneer Constructivists like Finnemore and Sikkink successfully demonstrated the causal impact of norms at a time when rationalist and materialist approaches dominated International Relations (IR) theory. In recent years, the success of this and other early Constructivist contributions has encouraged scholars to address some of their limitations, highlighting the centrality of norm contestation in the study of norms (Wiener Reference Wiener2008, Reference Wiener2014; Sandholtz Reference Sandholtz2007, Reference Sandholtz2008; Krook and True Reference Krook and True2010). On the basis of this literature, I identify and correct the limitations of the norms life cycle model (NLCM). Specifically, I reconceptualise the norm internalisation stage of the model.

In brief, the NLCM describes the life cycle of norms as a three-stage process: 1) norm emergence 2) norm cascade and 3) norm internalisation (Finnemore and Sikkink Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998: 895–6). The model relies on an understanding of norms as social facts in the Durkheimian tradition, which privileges the international ideational structure over process and the role of agents (Ruggie Reference Ruggie1998: 858). Because of this epistemological choice, the NLCM underplays the inherently contested nature of norms. Still the NLCM remains a powerful heuristic device. Furthermore, while not sufficiently explored theoretically or empirically, contestation is compatible with the first two stages of the model.Footnote 1 It is only in the internalisation stage, when enacting the norm becomes a matter of routine, that the model becomes problematic. Moreover, Finnemore and Sikkink erase contestation from the internalisation stage by definition. Indeed, they conceptualise norm internalisation as the stage at the extreme of a norm cascade where norms ‘are no longer a matter of broad public debate’ (1998: 895) and ‘achieve a “taken-for-granted” quality that makes conformance to the norm almost automatic’ (1998: 904). Footnote 2

If Finnemore and Sikkink’s description of what happens at the extreme of the norm cascade is inaccurate, what does happen instead? Building on Wiener’s theory of contestation (Reference Wiener2014), I reconceptualise norm internalisation as the phase at the extreme of the norm cascade in which inherently contested norms simultaneously enjoy formal validity, social recognition, and cultural validation among stakeholders.Footnote 3 This Dynamic Norm Internalisation stage recognises the dual nature of norms as structured and structuring (Wiener Reference Wiener2004: 19; Wiener Reference Wiener2008: 38). In other words, norms influence the behaviour of actors and actors’ practices endow norms with meaning, validity, and legitimacy. Indeed, the meaning of a norm only becomes apparent in context (meaning-in-use) (Wiener and Puetter 2009) and it is actors’ practices that endow them with validity and legitimacy (Wiener Reference Wiener2014). If stakeholders enjoy institutionalised and regular access to contestation in relation to a norm – what Wiener calls contestedness (2014) – they can generate validity and legitimacy for a shared understanding of said norm. If said meaning comes to simultaneously enjoy formal validity, social recognition and cultural validation (internalisation) this endows the norm with high structuring power.

The Dynamic Norm Internalisation stage is thus where the dual nature of norms most clearly manifests itself. This facilitates its analysis. Moreover, because first- and second-generation Constructivism focus on the structuring and structured nature of norms respectively, underplaying the other dimension of norms in the process, theorising the interplay between both dimensions in this stage creates a conceptual interface where scholars from both traditions can meet and collaborate.

The manuscript contributes to the study of norms in three ways. First, it recognises and theorises the role of contestation at the extreme of the norm cascade and beyond. This reinvigorates the NLCM and renders it useful to a broader group of scholars. Furthermore, it fosters a dialogue between first- and second-generation Constructivists. Second, the manuscript differentiates between norm legitimacy and its purported effect (compliance), which Finnemore and Sikkink’s conceptualisation of internalisation conflated. In this way, it increases the analytical power of the model. Finally, the manuscript explicitly addresses the question of norm change after internalisation. Contestation after internalisation can reinforce the validity and legitimacy of the internalised norm or it can lead to the loss of the norm’s formal validity, social recognition and/or cultural validation – that is, to norm regression. The manuscript further explains that norm regression, which sooner or later is likely to occur, can take the form of obsolescence, modification, or replacement. This last form of regression overlaps with norm emergence, making the model truly cyclical.Footnote 4

The remainder of the article is organised in five sections. First, the article briefly introduces first- and second-generation Constructivist perspectives on norm change. This provides the necessary background to discuss and reconceptualise norm internalisation. Second, it analyses Finnemore and Sikkink’s definition of norm internalisation and introduces the proposed reconceptualisation as well as the regression stage. To do so it relies on examples of human rights norms. Specifically it references the gender equality norm, the rights of climate refugees, the ban on child labour, and the right to self-determination. Third, it empirically demonstrates the usefulness of the proposed conceptualisation by assessing its descriptive power vis-à-vis that of the original definition in the case of the norm that prohibits torture. Fourth, it explores how further engagement with the contestation literature could contribute to enhancing the first two stages of the NLCM. Indeed, while norm contestation is compatible and even anticipated in these stages, its role remains underdeveloped. Finally, the conclusion reflects on how Dynamic Norm Internalisation improves the NLCM in light of the case study and on the broader implications of the argument.

II. First- and second-generation perspectives on norm contestation

Since the early 1990s, Constructivism has brought the study of norms to the forefront of IR theory. A ‘first wave’ of Constructivist norm studies (Wunderlich Reference Wunderlich, Muller and Wunderlich2013: 23, 26; Cortell and Davis Reference Cortell and Davis2000: 66) focused on demonstrating the structuring power of norms and on explaining norm diffusion (Nadelmann Reference Nadelmann1990; Haas Reference Haas1992; Klotz Reference Klotz1995; Checkel Reference Checkel1997; Katzenstein Reference Katzenstein1996; Price Reference Price1998; Tannenwald Reference Tannenwald1999; Risse, Ropp and Sikkink Reference Risse, Ropp and Sikkink1999). In doing so, they treated norms as fixed entities (Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2010), thereby underplaying their constructed nature. Furthermore, they privileged successful norms (Carpenter Reference Carpenter2007) and favoured linear and progressive narratives of norm diffusion where enlightened transnational (Western) elites educate backward states (Epstein Reference Epstein2012). A second wave of Constructivist scholarship challenged this characterisation, arguing that norms are elusive and fluid (Van Kersbergen and Werbeek Reference Van Kersbergen and Verbeek2007). Accordingly, norms can and will change over time (Krook and True Reference Krook and True2010: 104; Sandholtz Reference Sandholtz2008: 101–31). These scholars also emphasised the prevalence of contestation and conflict over convergence (Acharya Reference Acharya2004, Reference Acharya2013; Wiener Reference Wiener2008).

However, there are critical differences amongst Constructivists who study norm contestation. First-generation Constructivists focus on the structural power of socially constituted norms in a community with a given identity. For them contestation is relevant insofar as it can undermine or strengthen norm robustness – that is, the validity and facticity of norms (Sandholtz and Stiles Reference Sandholtz and Stiles2009; Deitelhoff and Zimmermann Reference Deitelhoff and Zimmermann2013; Bower Reference Bower2016; Zimmermann et al. 2018; Müller and Wunderlich Reference Müller and Wunderlich2018). In this sense, they share the epistemology of first-wave scholars. In turn, second-generation Constructivists adopt a critical perspective. They focus on access to contestation and on how practices of contestation change norms. They do so not to understand the effect of contestation on norm robustness but to elucidate how conflict affects norm change (Wiener 2018: 40–2). Accordingly, while scholars in both traditions seek to further our understanding of the interplay between norms and contestation practices, they approach their work in a manner that rarely intersects.

Yet, first- and second-generation Constructivists share an understanding of norms as both structured and structuring. Furthermore, their contributions are also complementary. On the basis of their complementarities, I reconceptualise norm internalisation and create a conceptual interface where scholars in both traditions can collaborate.

The most comprehensive theorisation of norm contestation is Antje Wiener’s Theory of Contestation (2014). The author explains that norms acquire a specific meaning only when they are applied – what she calls meaning-in-use (Wiener and Puetter 2009: 2, 5; Wiener Reference Wiener2008: 4). This makes context critical to understanding norms. Because there are persistent national and regional differences that shape the way norms are interpreted (Wiener Reference Wiener2014: 5), Wiener argues that to assess the validity of a norm we must consider its formal validity and social recognition, as first-generation Constructivists do, but also its cultural validation (Wiener Reference Wiener2017a). Accordingly, in her theory Wiener establishes three segments on the cycle of norm validation i.e., formal validation, social recognition (or habitual validation) and cultural validation (Wiener Reference Wiener2014: 7). The formal validity of a norm refers to the basic framework of reference for interpreting and implementing norms. It is created by legal language, for example in the form of treaties, as a result of international negotiations. Legalisation endows norms with authority because modern societies perceive the law as legitimate (Kratochwil Reference Kratochwil1989: 15, 95–129). In turn, a norm’s social recognition entails social interactions enacting and validating specific meanings of the legal rule. GroupsFootnote 5 develop social reference frameworks through repeated interactions. These provide guidance for the implementation and interpretation of norms, rules and principles, which grants them social recognition (Wiener Reference Wiener2008: 4). Finally, cultural validation entails legitimising the contextualised meaning of a norm across different regions and cultures.Footnote 6 Norms are highly contested when individual norm-users, such as public servants and judges, actually implement the norm (Wiener Reference Wiener2014: 19 and 29–30; Wiener Reference Wiener2008: 4–7). This makes norm convergence exceedingly difficult.Footnote 7

Nonetheless, contestation does not necessarily lead to conflict. Whether contestation culminates in conflict or consensus over the meaning and validity of norms depends on how international actors conduct normative encounters (Wiener Reference Wiener2017b: 114). Specifically, contestation can lead to consensus if normative encounters take the form of an inclusive, regular, and institutionalised dialogue between stakeholders. This is what Wiener calls contestedness (2014: 3).Footnote 8 To assess contestedness, we must evaluate the degree to which stakeholders are free to implement a norm (reactive contestation) and to change the meaning of the norm ‘through purposeful and normative ‘pro-action’ (proactive contestation) in all stages of norm implementation with reference to all forms of norm validation (Wiener Reference Wiener2017c: 7).

Drawing from Owen and Tully, Wiener relies on the quod omnes tangit principle (what touches all must be approved by all) to further argue that the practices of all stakeholders should count (2018: 3). The legitimacy of norms depends on access to contestation in relation to all three practices of validation for all those the norm governs. Still access to contestation is not equally available to stakeholders and it must be generated to ensure fair and successful global governance. In the absence of access to contestation for all stakeholders unavoidable contestation will likely lead to conflict (Wiener Reference Wiener2014: 30). Thus, the structuring power of norms over global governance partially depends on the degree to which those individuals affected by a norm can debate its meaning and proper implementation, compromise, and reach consensus (Wiener Reference Wiener2014: 30).

The likelihood of conflict or consensus as a result of contestation also depends on the type of contestation that takes place. Deitelhoff and Zimmermann explain that contestation around the application of norms (applicatory contestation) brings clarity, specifying when and how specific norms apply (2013: 1). This process often strengthens the norm. In contrast, contestation over the validity of a norm (validity or justificatory contestation) ‘questions the norm as’ and can, over time, weaken it (Deitelhoff and Zimmermann Reference Deitelhoff and Zimmermann2013: 1). Accordingly, applicatory contestation is likely to reassert the validity of a norm. In contrast, justificatory contestation can undermine it over time.

Nevertheless, justificatory contestation is not enough to erode the validity of a norm. Contestation weakens norms when there are no sanctions in response to it (Haas Reference Haas1990; Olsen Reference Olsen2001; Panke and Petersohn Reference Panke and Petersohn2011). Indeed, it is the absence of condemnation and not the challenges themselves that weaken norms. Accordingly, the validity of a contested norm will remain intact if stakeholders reject justificatory contestation efforts (Zimmermann et al. Reference Zimmermann, Deitelhoff and Lesch2017: 10).

Because norms are inherently contentious, all norms, including norms that enjoy high validity, can be contested and plausibly die (McKeown Reference McKeown2009). However, norms don’t just disappear. Percy and Sandholtz explain that because norms are resilient they are more liable to be become obsolete, modified, or replaced than to disappear (2017: 13–15). Norms obsolescence takes place because of ‘broader systemic changes in which an entire social system or domain of behavior disappears’ (Percy and Sandholtz Reference Percy and Sandholtz2017: 16). In this case, norms no longer influence global affairs because the context in which they operate ceases to exist. Examples of obsolete norms include the norm prohibiting unrestricted submarine warfare and the norms governing cross-border communications by telegraph (Percy and Sandholtz Reference Percy and Sandholtz2017: 16). A norm might also undergo significant modifications that weaken its validity. Norms constantly change. They become broader, narrower, more (or less) qualified by exceptions as a result of applicatory contestation. Contestation of an internalised norm can lead to change because, for example, the material and ideational context in which the norm exists undergoes deep transformations. This is exemplified by the norm against mercenary use (Percy and Sandholtz Reference Percy and Sandholtz2017: 17). Finally, norms can also be replaced. If a norm ceases to regulate a specific conduct, for example as a result of justificatory contestation, another norm will replace it. Percy and Sandholtz explain that as stakeholders abandon the old norm, ‘a replacement norm is being advocated and supported’ (2017: 18). This is the case of the prohibition of wartime plundering (Percy and Sandholtz Reference Percy and Sandholtz2017: 18).

III. Dynamic norm internalisation

The NLCM describes norms’ impact on international politics as a three-stage process (Finnemore and Sikkink Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998: 895–6). In the first stage, emergence, norm entrepreneurs attempt to persuade states to adopt a new norm. When a critical mass of states adopts the new norm (tipping point), the second stage, norm cascade, begins. In this stage socialisation leads enough states and enough critical states to endorse the new norm. This redefines appropriate behaviour for some relevant subset of states. At the extreme of the norm cascade, norms are internalised.

In the NLCM, if and when norms reach the internalisation stage, they ‘acquire a taken-for-granted quality and are no longer a matter of broad public debate’ (Finnemore and Sikkink Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998: 895). Finnemore and Sikkink explicitly describe internalised norms as ‘naturalized’ norms (Finnemore and Sikkink Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998: 904). This renders them static. The authors also privilege norm convergence over contestation. Indeed, in their discussion of norm internalisation Finnemore and Sikkink highlight the ‘‘‘isomorphism’’ among states and societies’ (1998: 905). This statement is at odds with recent scholarship, which argues that contestation actually prevails over convergence in multiple areas of global governance (Bailey Reference Bailey2008; Wiener Reference Wiener2008; Lantis Reference Lantis2011; Bob Reference Bob2012; Acharya Reference Acharya2013).

Internalisation is a product of habit and institutionalisation (Finnemore and Sikkink Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998: 904–5), in which lawyers, professionals, and bureaucrats serve as agents of gradual normative and political convergence. Their agency, however, is limited because in the internalisation stage agents do not engage with the norm in a generative capacity. Instead, they ensure conformity. In this sense, internalisation seems at odds with the rest of the model. Indeed, norm emergence and norm cascade focus on the practices of agents, notably norm entrepreneurs and transnational advocacy networks.

Furthermore, in the NLCM, conformance to internalised norms is almost automatic (Finnemore and Sikkink Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998: 904). In this way, Finnemore and Sikkink’s conceptualisation of norm internalisation conflates norm validity and compliance to it. This is of limited analytical usefulness.Footnote 9 Assessing the structuring power of norms at the extreme of the norm cascade requires that we differentiate actors’ relation with the norm (the validity and legitimacy of the norm from the perspective of stakeholders) from their behaviour (compliance). In this way, we can empirically establish the impact of the former on the latter.

Finally, while the NLCM does not claim that internalisation is the last stage in the life cycle of norms, it does not provide the conceptual tools to think about norm change beyond internalisation either. The fact that there is no discussion of what might happen after internalisation makes it the de facto final stage of the life cycle of norms. This unwittingly validates the notion that NLCM embodies the kind of bias towards linear and progressive narratives of norm change in early Constructivist literature that has come under criticism in the past decade (Krook and True Reference Krook and True2010; Epstein Reference Epstein2012).

In sum, internalisation as conceptualised in the NLCM undermines its usefulness for scholars who take contestation seriously. Yet the notion of norm internalisation is not incompatible with the contestation literature. In essence, norm internalisation captures high norm validity among stakeholders. Validity endows norms with structuring power, including an increase in the likelihood of compliance. Both first- and second-generation Constructivists would agree on this point. Furthermore, the contributions of both traditions are critical to overcoming the limitations of the NLCM.

First and foremost, Wiener’s distinction between formal validity, social recognition, and cultural validation adds necessary complexity to the study of norm internalisation. Cultural validation, in particular, is a previously missing (Wiener Reference Wiener2017a: 15) yet indispensable dimension of norm validity. The idea of ‘norm adjacency’ (Finnemore and Sikkink Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998) speaks to the importance of cultural difference in the diffusion of norms, but only as a parameter. Cultural validation, in contrast, emphasises local agency in interpreting and thus creating the norm. For Wiener and other second-generation Constructivists (Acharya Reference Acharya2004) understanding practices of cultural validation is necessary to understand how norms gain legitimacy (Wiener Reference Wiener2017a: 15, fn 57). Second, this literature forces us to acknowledge that internalised norms are still contested. The NLCM suggests that internalised norms are uncontested and stable. This is incorrect. Because norms are intersubjective, they are inherently contentious. Moreover, in a world of enduring cultural differences, they are likely to be contested. For this reason, the ‘taken-for grantedness’ of internalised norms is an unstable, if powerful, state. This demands the explicit recognition that internalisation is not a final stage in the life cycle of norms. Finally, the contestation literature also insinuates that contestation is necessary for internalisation. Applicatory contestation can foster the validity of a norm. In turn, regular and institutionalised access to contestation (contestedness) enables dialogue and thus compromise and consensus over the meaning and validity of norms. This endows norms with legitimacy.

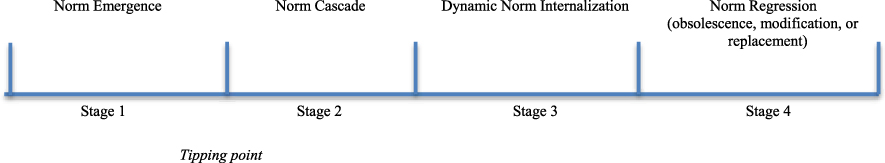

In line with these arguments, I reconceptualise norm internalisation as the phase at the extreme of the norm cascade in which inherently contested norms simultaneously enjoy formal validity, social recognition, and cultural validation among stakeholders. In this Dynamic Norm Internalisation stage norms enjoy the highest possible validity and legitimacy. This is the result of compromise or even consensus around a prevailing understanding of a norm in a particular context. In turn, internalisation increases the structuring power of norms, including the likelihood of compliance. Not all norms will become internalised and those that do are unlikely to remain internalised.Footnote 10 Accordingly, I incorporate a fourth stage in their life cycle: Norm Regression. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1: Modified Norms Life Cycle

While Finnemore and Sikkink focus on social recognition, I argue that a norm at the extreme of the cascade stage possesses not just social recognition, but also formal validity and cultural validation.Footnote 11 Indeed, these are irreducible dimensions of norm validity. Consider the case of a norm that enjoys formal validity but lacks cultural validation. That is the case of gender equality as enshrined in the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). With 189 state parties, CEDAW is the most ratified human rights treaty. This firmly establishes the formal validity of the gender equality norm. However, it is also the human rights treaty with most reservations, which speaks to the absence of agreement over the contextualised meaning of gender equality across different cultures. In other words, an overwhelming majority of states supports the norm in principle but they disagree on its actual scope. This situation led to compromises in the language of the treaty as well as the aforementioned reservations (Freeman Reference Freeman2009: 6) and continues to permeate the diffusion and implementation of the norm around the world (Zwingel Reference Zwingel, Caglar, Prügl and Zwingel2013). Indeed, CEDAW’s lack of cultural validation helps explain its uneven implementation (Krook and True Reference Krook and True2010: 112) in spite of its legal status. This observation substantiates the expectation that validity across all three dimensions is necessary for the high level of structuring power expected from internalised norms. Furthermore, in a world of enduring cultural differences, the challenges to generate cultural validation for the gender equality norm are significant.

Cultural validation is not, however, sufficient to generate the ‘taken for granted’ appearance and high compliance we associate with internalised norms. Formal validity is equally relevant to the internalisation of a norm. Consider the case of the rights of climate refugees. Notwithstanding the increasing recognition that these rights do exist, as the Global Compact on Refugees illustrate (UN General Assembly 2018), this norm lacks formal validity. The rights of refugees are clearly established in the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugee (Refugee Convention). Furthermore, the interpretation of the definition of refugee in the Refugee Convention has evolved through time to reflect developments regarding ‘the meaning of persecution and the bases on which human beings inflict severe harm on others’ (McAdam Reference McAdam2009: 579). This has led, for example, to establishing a rationale for the recognition of socioeconomic refugees (Foster Reference Foster2007). Yet the current legal frameworks, including the jurisprudence and scholarly work on the rights of refugees, do not provide the necessary basis to establish the formal validity of climate refugees’ rights (Cournil Reference Cournil, Mayer and Crépeau2017). In their absence, the validity and legitimacy of the norm are not well established. This negatively impacts its structuring power.

Social recognition is just as significant as cultural validation and formal validity. Consider the case of a norm that is endowed with formal validity but lacks social recognition – that is, the norm is legally binding but relevant actors do not invoke when assessing what constitutes appropriate behaviour. The ban on child labour illustrates this dynamic. The 1989 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) codifies children’s right to be free from commercial exploitation (CRC Article 32). Yet since the 1970s grass-roots movements of working children and youth have contested the child labour ban norm, claiming the ‘right to work’ and striving for better working conditions (Liebel Reference Liebel, Hanson and Nieuwenhuys2012). The challenge of working children to the child labour ban norm fundamentally undermines its validity and legitimacy. In their interactions and self-advocacy, these stakeholders purposefully deny the child labour ban norm social recognition and enact instead alternative norms. This weakens the legitimacy of the norm and also negatively affects its structuring power.

The proposed conceptualisation of internalisation creates different expectations regarding the critical actors in this stage, their motivations, and the mechanisms underlying norm internalisation and regression. I summarise these expectations in Table 1. Lawyers, professionals and bureaucrats can help endow a norm with formal validity, social recognition, and cultural validation but so can a myriad of other actors. For example, negotiators have privileged access during the negotiation stage of the norm where formal validity begins.Footnote 12 Alternatively, judges play a critical role in interpreting norms and constructing their meaning-in-use. In turn, social recognition depends on groups, which vary from norm to norm and cannot be defined a priori. Finally, all norm implementers can contribute to endowing norms with cultural validation. Depending on the norm, this process includes only a select few, as in the case of the prohibition of nuclear weapons, or hundreds of thousands of implementers, as in the case of human rights.

Table 1. Modified Stages of Norms*

* Innovations to the NLCM are emphasised.

** Justificatory Contestation is a mechanism of norm emergence and efficacy considerations can motivate it – see Norm Replacement. I did not include it here because it is beyond the scope of this paper to modify the first two stages of the NLCM

Regarding actors’ motives, conformity remains relevant in relation to formal validity and social recognition. On the other hand, it is the need to implement the norm that prompts individual stakeholders to establish (or deny) cultural validation. In terms of dominant internalisation mechanisms, Finnemore and Sikkink highlight institutionalisation and habit. These mechanisms generate formal validity and social recognition respectively. In relation to cultural validation, I emphasise individual stakeholders day-to-day practices. These practices give meaning to the norm (meaning-in-use) in line with stakeholders’ pre-existing ‘normative baggage’ (Wiener Reference Wiener2008: 57). Among these practices, applicatory contestation is likely to play a prominent role because it helps define the scope of the norm. In addition to this, because the way individual stakeholders interpret the norm is likely to vary across national borders and regions, I argue that inter-national dialogue is also a dominant mechanism of cultural validation.Footnote 13 Indeed, it facilitates global consensus, or at least compromise, over the meaning and validity of the norm.

Finally, I identify regular and institutionalised access to contestation for stakeholders (contestedness) as an antecedent condition for internalisation. Such access is indispensable for diverse stakeholders to take ownership of the norm and endow it with validity and legitimacy.

Most importantly, I contend that internalised norms continue to be part of a public debate and subject to contestation. Whether contestation strengthens or undermines the internalised status of a norm depends on contestedness, the type of contestation that takes place, and the reaction of domestic and international audiences to contestation.

First, high contestednessFootnote 14 enables the dialogue necessary to generate compromise or even consensus over the meaning and validity of a norm.Footnote 15 The possibility to engage in applicatory contestation is, in turn, necessary to generate norm legitimacy. Hence, we would expect norm internalisation to be more frequent in areas of global governance where institutionalised and regular access to contestation is high.Footnote 16 In contrast, in areas with low contestedness, internalisation is improbable.

Contestedness is not exclusively a matter of the structural conditions that enable or impede access to contestation. The strategies that norm advocates utilise can also shape contestedness. When advocates rely on vertical mechanisms of norm change, such as education and shaming, over the promotion of dialogue between stakeholders they undermine the possibility of internalisation. Yet the literature on norm diffusion seems to favour these strategies (Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1999; Park Reference Park2005; Bob Reference Bob2012; Hadden and Jasny Reference Hadden and Jasny2017), both reflecting and reinforcing advocates’ preferred strategies. In contrast, recent theoretical developments, notably the concept of communicative entrepreneurs (Gonzalez Ocantos Reference Gonzalez Ocantos2018), emphasise the effectiveness of open-ended dialogue in the promotion of new norms. Horizontal mechanisms of norm change such as this are arguably better suited to generate consensus and compromise over the meaning and validity of norms than vertical mechanisms. Therefore, they are also more likely to lead to norm internalisation.Footnote 17

Finally, I must underscore that contestation will continue after internalisation because norms are inherently contested and the contexts in which they operate change. Therefore, contestedness is necessary for internalised norms to retain their legitimacy through stakeholders’ access to validation practices.

Second, applicatory contestation is likely to reaffirm the norm’s legitimacy while justificatory contestation can eventually lead to norm regression. Indeed, applicatory contestation facilitates compromise and consensus over the specific meaning and proper implementation of norms. Alternatively, justificatory contestation is more likely to generate conflict and prevent norm internalisation. Unchallenged justificatory contestation around an already internalised norm could lead to norm replacement. If stakeholders do not condemn the challenge to the norm, the norm’s social recognition weakens and the norm might regress. On the other hand, sanctions, or at least objections, to justificatory contestation may strengthen the validity of the norm. Moreover, stakeholders’ access to these measures in defence of the norm would have a positive impact on its legitimacy.

Therefore, I postulate that internalised norms are not, and cannot be, a product of the absence of public debate. Neither are they apt to continue being internalised without contestation and widespread access to contestation. Indeed, absence of contestation is more likely to indicate norm obsolescence than norm internalisation.

Third, while I agree with Finnemore and Sikkink that actors tend to comply with internalised norms, I argue that compliance is not automatic. Finnemore and Sikkink depict automatic conformance as a defining characteristic of internalised norms (1998: 904). This makes internalised norms indistinguishable from their purported impact on actors’ behaviour. Furthermore, defining the universe of internalised norms in terms of robust norms (norms with high validity and facticity) unwittingly directs our attention to a small number of norms at the extreme of the norm cascade. The reason is that, while high validity positively affects compliance, it is not the only factor that influences actors’ behaviour. A number of factors unrelated to the norm itself are likely to determine its facticity. Accordingly, a definition of norm internalisation focused solely on validity constitutes a better guide for the study of norms and their structuring power.Footnote 18

In relation to this, the proposed conceptualisation is agnostic with regards to the type of explanations actors will use to justify deviant behaviour. According to McKeown, Finnemore and Sikkink argue that violators justify any abrogation of an internalised norm with rationalisations that strengthen it (2009: 8). This makes sense in a context in which internalised norms are, by definition, no longer debated. Because Dynamic Norm Internalisation anticipates less convergence and more conflict around said norms, including efforts to replace them, it also expects that justifications will vary. Indeed, some might purposefully attempt to undermine the validity of the norm.

Finally, my approach to compliance with internalised norms also differs from Finnemore and Sikkink’s insofar as I recognise the potential positive impact of contestation over compliance. Indeed, I agree with Hansen-Magnusson et al. when they argue that access to contestation is a ‘virtue’ for compliance (2018: 4).

Because they are inherently contested, norms are unlikely to remain internalised. Internalisation thus cannot be the last stage of the NLCM. Consequently, I argue that the model should explicitly discuss norm regression. I define norm regression as the phase in which the formal validity, social recognition and/or cultural validation of an internalised norm weakens. In other words, it entails the de-internalisation of a norm. Norm regression might involve renewed disagreement over the validity and meaning of the norm. All other things being equal, it also undermines the likelihood of compliance.

It is worth mentioning that there is nothing in the NLCM that precludes norm regression. As a matter of fact, Finnemore and Sikkink anticipate norm regression in their discussion of norm emergence. Specifically, they explain that ‘new norms never enter a normative vacuum but instead emerge in a highly contested normative space where they must compete with other norms and perceptions of interest’ (1998: 897). This implies that new norms replace old norms.

Norm replacement is, however, only one of the forms that norm regression can take. Building on the work of Percy and Sandholtz, I argue that norm regression can take the form of norm replacement, modification, or obsolescence (Figure 1). Norm replacement signals the end of the existing consensus over the meaning and validity of the internalised norm leading to its de-internalisation. All other things being equal, norm replacement undermines the likelihood of actors’ compliance with the norm. Furthermore, the possibility of norm replacement transforms the NLCM into a truly circular model. Indeed, norm replacement coincides with norm emergence, which speaks of a mutually constitutive relation between regressing and emerging norms.

Consider the example of the self-determination norm, which replaced the right to conquest.Footnote 19 Acting as norm entrepreneurs, the United States and the USSR advocated for the self-determination norm vis-à-vis European great powers after WWI. They did so in spite of substantial disagreements over the scope of the norm.Footnote 20 Simultaneously, these norm entrepreneurs undermined the validity of the right to conquest norm through justificatory contestation. President Wilson, for example, proclaimed that ‘the world has a right to be free from every disturbance of its peace that has its origin in aggression’ and called for ‘a virtual guarantee of territorial integrity and political independence’ (1917).

Norm replacement speaks to the impossibility of a normative vacuum in an area that was previously regulated. Once a norm is in place, it cannot be replaced by no-norm. This implies that for a norm to regress it is necessary for a viable alternative to exist. In the case of the right to conquest, self-determination enabled replacement. However, alternative norms are not always available. In their absence, I argue that contestation will more likely lead to norm modification than replacement.

As in the case of norm replacement, norm modification implies the erosion of consensus over the validity of the internalised norm. All other things being equal, it also diminishes the likelihood of actors’ compliance with it. Consider once again the case of self-determination. In the second half of the twentieth century, an interpretation of the self-determination norm that stipulates that all people have the right to freedom from colonial domination and foreign occupation and that this right validates unilateral secession became internalised.Footnote 21 Yet further contestation led to a changed understanding of the norm of self-determination in the post-decolonisation era. In this new and more restricted interpretation of the norm, people have the right to ‘enjoy autonomy or to form self-government within their current state’ (Kang Reference Kang2018: 21). Only when every effort to achieve this has failed might secession be deemed acceptable (Vidmar Reference Vidmar2010). This modified understanding of self-determination is not internalised.

Finally, a norm might also regress by becoming obsolete. This happens when the context in which it operates ceases to exist. The rules outlined in the UN Charter establishing an international trusteeship system to oversee the decolonisation process on the basis of the self-determination norm exemplify obsolete norms. With the independence of Palau, the last U.N. Trust Territory, there was no reason for the Trusteeship Council to continue to exist. Today, the aforementioned rules continue to be part of the UN Charter and thus enjoy formal validity. Yet they are systematically neglected because there are no non-self-governing territories left. Most stakeholders consider these rules are now irrelevant and some have even called for the deletion of Chapter XIII of the UN Charter (High-level Panel on Threats, Challenges and Change in Matz Reference Matz2005: 48). While obsolete norms might reappear they would not automatically become internalised. In our example, the system of trusteeship could be reimagined to assist failed states (Mohamed Reference Mohamed2005). However, while the formal validity of the trusteeship system norms is intact, their social recognition and cultural validation would have to be re-established.

We can analyse norm replacement, modification, and obsolescence on the basis of Finnemore and Sikkink’s three-criteria approach – that is, actors, motives and mechanisms. The dominant mechanisms behind regression will vary depending on the form norm regression takes. Neglect drives to norm obsolescence. In turn, applicatory contestation underlines norm modification. Finally, justificatory contestation can lead to norm replacement. The motivations of the actors involved will also vary. Based on our previous discussion, stakeholders might neglect a norm making it obsolete because it is no longer relevant. Alternatively, they will modify an internalised norm because a changed material context or the tension between new norms and the old norm encourages ‘accommodations’. Arguably, the dominant mechanism behind norm modification is successful applicatory contestation – unsuccessful applicatory contestation of an internalised norm, in contrast, reaffirms the norm’s status. In instances of norm replacement, stakeholders as norm entrepreneurs will challenge the validity of the norm. One of the reasons is that stakeholders are ideologically committed to a new norm. The new norm might become internalised in time, but that is not necessary for the old norm to regress.

Does norm regression always take place? Not necessarily. An internalised norm might regress or remain internalised depending on a variety of factors. Norm obsolescence is more likely to occur in times of profound material change or normative change. In the case of the rules establishing an international trusteeship system to oversee the decolonisation process the independence of all U.N. Trust Territories constituted said change. Regarding norm replacement, the likelihood of a norm regressing in this manner varies with the stability of the context and the strength of pro status quo actors. In terms of the normative context, deep-rooted practices and high institutionalisation, particular if the norm is embedded in wider normative structures, bring about stability for internalised norms (Percy and Sandholtz Reference Percy and Sandholtz2017: 15; Lantis and Wunderlich Reference Lantis and Wunderlich2018: 572). Such context would empower actors who defend the normative status quo (norm antipreneurs) and endow them with strategic advantages over norm entrepreneurs (Bloomfield Reference Bloomfield2016: 322).Footnote 22 For example, antipreneurs can rely on the formal validity of the internalised norm to undermine arguments in support of the new norm. In contrast, a volatile context characterised by major normative and/or material changes creates advantages for norm entrepreneurs and make replacement more likely. Not only do these changes make contestation more likely (Sandholtz and Stiles Reference Sandholtz and Stiles2009: 10–11) but, all other things being equal, they also empower norm entrepreneurs vis-à-vis antipreneurs. The reason is that internalisation is inherently unstable. Furthermore, the internalised meaning of the norm is context-dependent. In a changing context, justificatory contestation is more likely to succeed and the internalised norm replaced. In the case of the self-determination norm replacing colonialism, WWI and WWII defined this changing context.

Norm modification is, in contrast, less onerous and thus more likely to occur. Because it does not entail an attack on the norm, norm modification undermines the strategic advantages pro status quo actors enjoy in norm replacement processes. Indeed, proposals to modify the norm can be framed as necessary for the continuous relevance of the norm. Change advocates often argue that new circumstances or previously unforeseen circumstances compel change. Therefore, all other things being equal, if an actor successfully frames their contestation efforts in terms of norm modification as opposed to norm replacement, they are more likely to succeed. If they do, their proposed understanding of the norm and its proper scope and application is likely to be subject to contestation and could eventually become internalised. In the case of the self-determination norm redefined to entail a limited right to unilateral secession internalisation has not yet taken place.

By definition, a norm regresses because the formal validity, social recognition, cultural validation (or a combination of these) of an internalised norm weakens. That begs the question: Is the weakening of a specific dimension of validity more likely to lead to one form of regression than others? This is plausibly the case. We already established that obsolescence arises primarily from the neglect of stakeholders, who no longer find use in the norm and cease to reference it. Thus, neglect might arguably undermine the norm’s social recognition first causing the norm to become obsolete. That has been the case in regard to the rules outlined in the UN Charter establishing an international trusteeship system to oversee the decolonisation process. In turn, stakeholders often modify norms on the basis of efficacy and normative considerations through applicatory contestation. Because these considerations presumably vary across national and regional contexts, the erosion of consensus over a norm’s cultural validation is likely to trigger norm modification.Footnote 23 In the case of the self-determination norm, numerous peoples around the world have found themselves limited by an understanding of the norm that does not apply to their circumstances – that is, they are not colonies or occupied territories, leading to justificatory contestation and norm modification. Finally, both efficacy considerations and ideological commitment motivate stakeholders to replace norms through justificatory contestation. Norm replacement overlaps with the emergence of a new norm. However, before the new norm becomes embedded in international and domestic legal frameworks, acquiring formal validity at the expense of that of the old norm, it is arguably the social recognition and cultural validation of the old norm that are successfully contested. Therefore, loss of social recognition and cultural validation is likely to lead to norm replacement. In the case of the right to conquest norm, the United States and the USSR undermined the validity of the norm and advocated for the self-determination norm while the right to conquest still enjoyed formal validity.

IV. Norm internalisation: The case of the prohibition of torture

Previous sections outlined the shortcomings of the internalisation stage in the NLCM, notably 1) the limited agency of actors, 2) the negation of contestation, 3) the conflation of norm validity and legitimacy with compliance and 4) the assumption that in the rare instances of non-compliance, actors will justify their behaviour in a manner that reinforces the norm. Yet, it is still necessary to empirically validate this critique. Accordingly, this section assesses the descriptive power of the proposed conceptualisation of internalisation vis-à-vis Finnemore and Sikkink’s.

To undertake this comparison, I outline the expectations derived from each conceptualisation and test which narrative best accommodates the empirical evidence related to the life cycle of the norm that prohibits torture. This norm has almost unparalleled high validity, which is the common distinguishing feature of both conceptualisations. It also enjoys high compliance.Footnote 24 Furthermore, the norm is still internalised. This enables us to subject it to Finnemore and Sikkink’s conceptualisation, which does not theorise what happens after internalisation.Footnote 25 For these reasons, it is an ideal case for this exercise.

If Finnemore and Sikkink’s conceptualisation were accurate, we should observe that social recognition endowed the prohibition of torture with a ‘taken-for-granted quality’. After that, the norm stopped being a matter of ‘broad public debate’. Moreover, conformance to the norm should have become almost automatic. Finally, any challenges to the internalised norm should have been justified in terms that helped reinforce its appropriateness. If, on the other hand, the proposed conceptualisation has higher descriptive power, we should observe that the prohibition of torture acquired a ‘taken-for-granted quality’ only after it gained formal validity, social recognition, and cultural validation. Moreover, applicatory contestation, under conditions of high contestedness, should have facilitated the cultural validation of the norm. Additionally, we should observe that stakeholders continued to contest the norm after internalisation. If the internalised norm was subject to justificatory contestation and remained internalised, we should also observe that stakeholders overwhelmingly condemned said contestation. In the absence of such condemnation, the internalised norm should have regressed. Finally, we should observe that compliance with the norm has not been ‘almost automatic’. Moreover, justifications for contestation and deviant behaviour might have not always reinforced the norm.

To reconstruct the trajectory of this norm alongside the aforementioned observable implications, I rely on secondary and primary sources, including NGO reports, government officials’ statements, and judicial decisions.

Actors, motives, and mechanisms that underlined the internalisation of the norm

To some extent, the NLCM satisfactorily explains the trajectory of the norm that prohibits torture. Ostensibly, its trajectory follows the stages outlined in the model – emergence, cascade, an, at the extreme of the norm cascade a ‘taken-for-granted’ quality among stakeholders. In the eighteenth century, torture became increasingly at odds with emerging ideas of fundamental human rights, rule of law, and legal security (Conze in Kesper-Biermann Reference Kesper-Biermann2018: 4). Acting as ‘norm entrepreneurs’ jurists, state officials, and philosophers engaged in a transnational dialogue that introduced the norm that prohibits torture (Hunt Reference Hunt2007: 97–112). Their argument relied both on principled and efficacy claims. Specifically, new legal developments meant that torture was no longer necessary to establish proof in criminal proceedings (Langbein Reference Langbein1977) nor was it considered effective as a means to obtain confessions (Kesper-Biermann Reference Kesper-Biermann2018: 4). These developments denied the infliction of pain any positive past connotations, undermining the legitimacy of torture (Silverman Reference Silverman2001). Moreover, torture was now perceived to be dangerous to the (civilised) social order (Barnes Reference Barnes2013: 16). Indeed, the developing notion of individual rights and security made it impossible for the state to justify torture as a means to keep its citizens safe (Hunt Reference Hunt2007). This process can be characterised as an instance of justificatory contestation, which the proposed conceptualisation on norm internalisation identifies as a critical mechanism of norm replacement. Norm replacement, in turn, overlaps with the norm emergence stage of norms.

Between 1734 and 1851, European states codified the prohibition of torture in legal norms (Kesper-Biermann Reference Kesper-Biermann2018: 7). This marked the tipping point that preceded this norm’s cascade. The cascade stage took place during the following century, as individual states throughout the world incorporated the norm in their legal systems (Kesper-Biermann Reference Kesper-Biermann2018: 5). In turn, the internalisation of the norm occurred in the second half of the twentieth century. International society integrated the prohibition of torture in international law (Kesper-Biermann Reference Kesper-Biermann2018: 7–8),Footnote 26 reflecting and strengthening its widespread social recognition.Footnote 27 Today, the norm enjoys ‘extremely high’ legitimacy worldwide (Dunne Reference Dunne2007: 277), particularly, albeit not exclusively (Liese Reference Liese2009: 18), among liberal states (Sikkink 1999: 520; Risse and Sikkink Reference Risse, Sikkink, Risse, Ropp and Sikkink1999: 8). Accordingly, a majority of the international community has ratified several global and regional treaties that institutionalise the prohibition of torture,Footnote 28 notably the 1984 United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT).Footnote 29

This brief account illustrates how the NLCM seemingly explains the internalisation of the norm that prohibits torture. Yet, it leaves out the critical process of cultural validation and downplays the agency of actors. Indeed, it overlooks stakeholders’ efforts to legitimise the norm at this stage through interpretation, adjudication, contestation, dialogue, and compromise. The proposed definition offers the advantage of directing our attention to the construction of the norm’s meaning-in-use, the role of contestation in this process, and the actors involved in it. It also emphasises the compromises that underline the global consensus around the meaning and legitimacy of the norm. Finally, the proposed conceptualisation provides evidence that the emergence of the norm that prohibits torture overlapped with the replacement of the norm that previously legitimised this behaviour.

The norm that prohibits torture acquired cultural validation through a process of contestation over what constitutes torture and other forms of ill-treatment. Case law was particularly influential in the process of constructing the norm’s meaning-in-use because the general human rights treaties that first established the prohibition of torture at the international level did not include a definition of the act (Rodley Reference Rodley2002: 468). This forced the courts to clarify the meaning of the norm in order to adjudicate cases. These decisions later influenced the prevailing meaning-in-use adopted in the CAT. Throughout a 30-year dialogue between interpreters of different regions, the norm reinforced its formal validity and social recognition and acquired cultural validation. International actors agreed on a definition of torture through compromise and generated cultural validation for this specific interpretation of the norm. This definition of the prohibition of torture presents three fundamental characteristics. First, it maintains that the prohibition of torture is absolute. Second, it claims that severe pain and suffering characterise torture. Finally, it differentiates torture from other practices that illegally inflict severe pain and suffering on the basis of its purpose. Indeed, actors torture with a specific goal in mind, such as obtaining information that can presumably help the state preserve its security and that of its citizens (Rodley Reference Rodley2002; DeVos Reference De Vos2007).

This account cannot reconstruct the aforementioned dialogue in its entirety, but some actors and events stand out. While the literature pays relatively little attention to courts and judges,Footnote 30 as the interpreters of the norm they had a critical role in establishing its meaning-in-use. Footnote 31 In 1969, the European Commission of Human Rights (hereafter the Commission) ruled the first case on torture – Denmark et al. v Greece (Rodley Reference Rodley2002: 472). To do so, it had to interpret Article 3 of the European Convention, which prohibits torture and ill-treatment but does not define them. The Commission determined that severity of pain is the defining characteristic of illegal infliction of pain and that the distinction between torture and inhuman and degrading treatment lies in the fact that torture is an aggravated form of the latter because it has a purpose, e.g., to gain information or to punish (De Vos Reference De Vos2007: 4). Footnote 32 This is consistent with norm entrepreneurs’ arguments about the fundamental incompatibility between rule of law and modern society-state relations and torture, but it was not a foregone conclusion. Indeed, when the European Court of Human Rights decided Ireland v United Kingdom in 1976, it defined torture on the basis of the severity of the pain instead of the purpose behind its infliction. Accordingly, the Court concluded that, while it had engaged in inhuman and degrading treatment, the United Kingdom had not tortured.

Dissenting judges, human rights groups, and legal scholars successfully argued that modern medical and physiological techniques did not necessarily entail inflicting physical pain (Barnes Reference Barnes2016: 108). Furthermore, they explained that the general condemnation of torture had forced governments to use torture methods that left no trace in the bodies of the victim so they could deny it had ever happened (Kesper-Biermann Reference Kesper-Biermann2018: 10). For this reason, purpose and not suffering should be the determining characteristic of torture.

This meaning-in-use of the prohibition of torture gained traction. Eventually, the European Court reversed its position regarding the centrality of the severity of pain in the definition of torture (Yildiz 2016: 10). This meaning-in-use also prevailed in other regional contexts. For example, the Inter-American Convention to Prevent and Punish Torture does not even mention severe intensity of pain as a requisite to establish torture (1985: Article 2). Culminating these efforts to develop global consensus over the meaning-in-use of the norm, the CAT defined torture as an aggravated form of pain but it emphasised purpose as the determining characteristic (Rodley Reference Rodley2002: 475). This was a compromise between the preferences of states, such as the United Kingdom and the United States, which favoured a definition focused on severity, and human rights groups and other actors, which advocated for a purpose-based definition (Barnes Reference Barnes2016: 108–9) This brief discussion illustrates the continuous importance of contestation and norm stakeholders’ agency in generating validity around the prevailing meaning-in-use of the norm, which today enjoys a ‘taken-for-granted’ quality in most parts of the world. It also illustrates the importance of access to contestation in this process. Stakeholders, including governments, courts and activists had access to proactive contestation throughout the process, which legitimised the norm.

Contestation of the norm after internalisation

While there has not been widespread contestation over the validity of the norm that prohibits torture after internalisation, in the 1990s the conversation around the use of torture under exceptional circumstances reopened (Kesper-Biermann Reference Kesper-Biermann2018: 5–6). The most notorious case of contestation, albeit not the only one,Footnote 33 is that of the Bush administration engaging in justificatory contestation in the early 2000s. Because the United States has the resources to pressure states into accepting its normative preferences and because its historical role as a human rights entrepreneur endows it with the authority to advance new interpretations of existing norms (Keating Reference Keating2014: 2–3), their actions could have undermined the validity of the norm and lead to norm regression. Instead, both domestic and international audiences rejected the challenge, reinforcing the validity and legitimacy of the norm.Footnote 34

In the context of the war against terrorism, the Bush administration engaged in systematic efforts to make some extreme interrogation methods permissible. It also sought to refocus the definition of torture on the severity of the pain and suffering inflicted and not on their purpose. Following the President’s lead, the Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) in the Justice Department advocated to define physical torture as acts ‘equivalent in intensity to the pain accompanying serious physical injury, such as organ failure, impairment of bodily function, or even death’ (Bybee Memo 2002b: 176) and mental torture as acts resulting in ‘significant psychological harm of significant duration’ (Bybee Memo 2002b: 177). In an effort to reduce the scope of application of the norm, this OLC classified Al Qaeda and Taliban prisoners as ‘unlawful enemy combatants’. This is a category ‘beyond soldier and civilian’ to which the Geneva Conventions’ prohibition of cruel, humiliating and degrading treatment and torture did not apply (Bybee Memo 2002a: 136; Yoo Memo 2002: 221). Furthermore, Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld approved the use of methods such as yelling, stress positions, isolation, hooding, removal of clothing, and sensory deprivation (Rumsfeld Memo 2002: 237).Footnote 35

Resistance against these efforts to undermine the prohibition of torture always existed among some government officials and other actors who were aware of the memos. However, it increased considerably when the memos became public (Birdsall Reference Birdsall2016: 185). Domestically, criticism came from intelligence and law enforcement officials, senators, and, to some extent, public opinion Footnote 36 Lawyers within the State Department, navy, army, air force, and from the Joint Chiefs of Staff rejected the interpretation of torture the OLC advanced (Bowker Reference Bowker and Greenberg2006: 190). Members of the intelligence community opposed the guidelines in the Rumsfeld memos (Barnes Reference Barnes2016: 111). Admiral Mora, for example, argued that the practices authorised in the memo ‘constituted, at a minimum, cruel and unusual treatment and, at worst, torture’ (Mora 2004: 6). In Hamdan v Rumsfeld, the Supreme Court struck down the suspension of habeas corpus in Guantanamo and recognised the rights of enemy combatants (2006). In Congress, Senator John McCain championed the prevailing meaning-in-use of the norm. Specifically, he ensured Senate support for establishing the US Army Field Manual, which reflects this interpretation of the norm, as the standard for interrogation across all US agencies (McCoy Reference McCoy2006: 187). Finally, the Pentagon distanced itself from the administration’s revisionist interpretation of torture. Indeed, it released a new Army Field Manual that banned such interrogation techniques as nudity, hooding and waterboarding (United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary 2009: 23).

Internationally, states rejected the Bush administration’s revisionist narrative, in spite of the United States’ considerable power and influence (Keating Reference Keating2014). Rejection prevailed even among United States’ close allies, including the United Kingdom and other European powers (Hodgson Reference Hodgson2005: 12). In addition to these states, the International Committee of the Red Cross, the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, the UN Committee against Torture, the Council of Europe, and a myriad of human rights groups, all opposed United States efforts to redefine torture (Barnes Reference Barnes2016: 113). Furthermore, the European Court of Human Rights decided that European countries that cooperated with the United States in torturing prisoners had violated fundamental human rights (European Court of Human Rights 2018). This created more tangible repercussions for actors contesting the prevailing meaning-in-use and validity of the norm.

This antagonism led the Bush administration to withdraw the controversial memos. In 2014, it revoked the Bybee memorandum and replaced it with Acting Assistant Attorney General Daniel Levin’s new memorandum (Barnes Reference Barnes2016: 114). This memo, released to the general public, upheld the absolute prohibition of torture and abandoned Bybee’s redefinition of torture as extreme acts, while at the same time it still defined torture in relation to the severity of the pain and suffering inflicted and not the purpose of the act. The administration also replaced Rumsfeld’s memorandum with the Detainee Treatment Act of 2005 and reinstated the FM 34-52 Field Manual as the guideline for interrogation techniques (Barnes Reference Barnes2016: 114). The fact that the United States is a democracy fostered the existence of institutionalised spaces for contestation domestically and internationally. The active role of the Senate in condemning the arguments of the executive power, for example, was only possible because the Constitution makes both branches of government necessary participants in the conduct of foreign policy. High contestedness thus proved to be critical for the failure of the Bush administration’s challenge to the prohibition of torture. It also reinforced the legitimacy of the norm through stakeholders increased engagement with it.Footnote 37

This analysis demonstrates that contestation over the norm that prohibits torture continued after its internalisation. The Bush administration framed contestation as an effort to adapt the norm to local circumstances, that is, an instance of applicatory contestation. Yet, the administration’s efforts better fit the parameters of justificatory contestation. Hence, this instance of contestation created a real possibility of norm regression. The fact that United States’ efforts failed speaks to the validity and legitimacy of the prevailing meaning-in-use of the prohibition of torture. It also supports Panke and Petersohn’s arguments regarding the significance of resisting revisionist efforts to ensure the enduring legitimacy of a norm. Finally, it validates Bloomfield’s claims regarding the strategic advantages of norm antipreneurs in the context of norm emergence (2016). All in all, hostility towards contestation efforts reaffirmed the shared meaning-in-use of the norm (Birdsall Reference Birdsall2016:177). Moreover, it helped reinforce the norm’s formal validity,Footnote 38 social recognition, and cultural validation.Footnote 39 In addition to this, stakeholders increased engagement with the norm in order to protect it from the challenges of the Bush administration furthered its legitimacy.

Rationale for contestation and non-compliance with the norm

In the NLCM, when actors challenge an internalised norm they justify their behaviour on the basis of arguments that further legitimise it (Finnemore and Sikkink in McKeown Reference McKeown2009: 8). The fact that the Bush administration contested and violated the norm that prohibits torture but never rejected its overall validity supports this expectation. However, upon closer examination, we find that the administration backed a ‘different’ norm. Indeed, Assistant Attorney General Bybee and others sought to subvert the validity of the norm’s prevailing meaning-in-use. They did so by advancing a different interpretation of the norm on the basis United States’ exceptional circumstances and particular values.

From the perspective of the Bush administration, traditional laws of war sustained by reciprocity were no longer applicable in the context of the war on terror. Terrorism had changed the nature of international conflict requiring a shift in tactics (Lopez Reference Lopez2006), including the proper implementation of the norm that prohibits torture. To justify this change, Bybee relied on arguments of necessity (Bybee 2002b: 207–9) as well as self-defence (Bybee 2002b: 209–13). He backed these arguments with domestic and international case law. For example, he cited the aforementioned European Court adjudication of Ireland v United Kingdom (Bybee 2002b: 196–8) as well as the Israel Supreme Court’s decision in Public Committee Against Torture in Israel v Israel to justify a meaning-in-use of torture focused on gravity and not purpose (Bybee 2002b: 198–200). Bybee also employed domestic case law. Specifically, he relied on domestic courts’ views on the Eighth Amendment, which emphasise intent, to define torture (Bybee 2002b: 174–5, 187).Footnote 40

This last argument is of particular interest because it speaks to how the cultural background of implementing stakeholders affects the cultural validation of a norm. In the case of the United States, American exceptionalism shapes human rights foreign policy. It does so through the notion that the United States is a special nation with a moral right to exercise broad power in the world – what Forsythe calls providential nationalism (2011). From this perspective, ‘the US Constitution with its Bill of Rights is supreme, not to be trumped by any other law; treaties that are inconsistent with the Constitution cannot stand’ (Forsythe Reference Forsythe2011: 775). Accordingly, the Bush administration promoted a meaning-in-use of the norm that reflected not only current concerns with terrorism but also long-standing beliefs regarding the Constitution status vis-à-vis international law.

The proposed conceptualisation of internalisation anticipates and explains contestation of internalised norms. Accordingly, the fact that the United States challenged the validity of the prohibition of torture should not be interpreted as evidence of norm regression. Instead, it illustrates the fact that norms are inherently contentious. Indeed, even norms with a ‘taken-for-granted’ quality can be contested.

Compliance with the norm

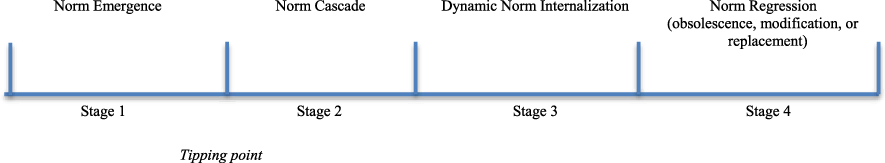

As anticipated, compliance with internalised norms does not meet the expectations of the NLCM. While compliance is relatively high, it cannot be properly characterised as ‘almost automatic’. Since the coming into force of the CAT, compliance with the norm that prohibits torture has remained stable at a 15 to 25 per cent, including during the Bush administration’s challenge (CIRI Human Rights Project).Footnote 41 (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2: Share of States with Frequent, Occasional, and No Torture Allegations

The rate of compliance might appear far from impressive but it is important to consider it in perspective. On average, there is a complete absence of allegations of torture in 20 per cent of the countries in the world. In addition to this, there is only a relatively small number of allegations of tortureFootnote 42 in 40 per cent of the countries of the world. This indicates that there is higher compliance worldwide with the norm that prohibits torture than with the prohibition of slavery (Global Slavery Index 2018), which Finnemore and Sikkink identify as a paradigmatic internalised norm (1998: 895).

In sum, while states recognise the validity and legitimacy of the norm that prohibits torture they sometimes fail to comply with it. Indeed, the practice of torture has persisted in spite of the high validity of the norm that prohibits it (McCoy Reference McCoy2006). Implicitly reflecting on the disconnect between the norm’s validity, on the one hand, and instances of non-compliance, on the other, Amnesty International observes that ‘[a]lthough governments have prohibited this dehumanizing practice in law and have recognized global disgust at its existence’, they still engage in torture (2014).

The NLCM cannot easily accommodate the tension between the validity of the prohibition of torture and instances of non-compliance. Dynamic Norm Internalisation is better equipped to do so because it differentiates between norm validity and the behaviour that it is purported to generate. The fact that violations coexist with the norm’s high validity and legitimacy simply demonstrates that norms alone do not determine states’ preferences or behaviour. Interests matter as well (March and Olsen 1998). Moreover, contradictory norms coexist in society and shape actors’ identity. Specific norms become more or less salient in different contexts (Weiner Reference Weiner1998: 440), affecting behaviour in different ways. Yet the high validity of the prohibition of torture still generates structuring power. For example it shapes debates about the fight against terrorism, even if it does not ensure the complete absence of the use of torture in the process.

Finally, the proposed conceptualisation highlights two other important dimensions of the question of compliance. First, non-compliance does not in itself indicate, or lead to, the regression of the norm. Validity and legitimacy alone do not explain compliance nor do their absence explain non-compliance. Second, if the meaning of a norm is not fixed, compliance is much more dynamic than the norm literature conveys. Indeed, because the meaning-in-use of the norm evolves so does our understanding of compliance. Consider the European Court adjudication of Selmouni v France (1999). In this case, the Court decided that what it did not consider torture in Ireland v United Kingdom (1976) constituted torture 20 years later. The same conduct was interpreted first as compliant with the norm and then as a violation of it because, in the European context, the meaning-in-use of the norm had changed. Specifically, the European Court increasingly recognised positive rights derived from the prohibition of torture, such as preventing abuse and punishing perpetrators (Yildiz 2016).

V. Beyond dynamic norm internalisation

While it is the internalisation stage that is truly at odds with the inherently contentious nature of norms, the contestation literature also has implications for the first two stages of the NLCM. Above all, it reveals that contestation plays a major role throughout the life cycle of a norm. First, specific forms of contestation function as critical mechanisms in different stages of the model. In the emergence stage, which overlaps with norm replacement, norm entrepreneurs challenge the normative status quo (along one or all dimensions of a norm’s validity) while simultaneously making a case for the new norm (Finnemore and Sikkink Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998: 897). Accordingly, unless the emerging norm regulates a completely new area (for example, as result of a recently developed technology), justificatory contestation enables norm emergence. In other words, justificatory contestation is the critical mechanism for norm change in the emergence stage.

Contestation also plays a significant role in the cascade stage. For Finnemore and Sikkink socialisation is the primary mechanism behind the diffusion of a norm after the ‘tipping point’, that is, after a critical number of actors have embraced it. This seems to assume a relatively straightforward process of norm diffusion, which the scholarship on contestation refutes.Footnote 43 In contrast, when it does take place, the widespread acceptance of a norm results from compromise and consensus through applicatory contestation over the meaning and validity of the norm. In other words, negotiation between actors with different interests and normative backgrounds is instrumental to the widespread acceptance of the norm.

To illustrate these arguments, let us consider the case study. The replacement of the norm that permits torture with its prohibition entailed challenging its validity (justificatory contestation) on the basis of both principled and efficacy claims, such as that torture was not an effective means to obtain confession. In turn, the norm cascade stage began with the codification of the new norm in Europe. In this stage, it was primarily applicatory contestation that endowed the norm with some degree of stability and validity, which in turn allowed its diffusion. In particular, the case analysis brings our attention to the case law that preceded the CAT, which was critical in this task.

Second, during the first and second stages of the NLCM the meaning of a norm is not stable. While inherently contested norms enjoy temporary stability if they become internalised, in the first two stages of the NLCM the meaning of the norm is subject to disagreement. This is an under-studied dimension of norm change in the model. Amongst entrepreneurs, and between them and early supporters, contestation over the meaning of the norm is a critical feature of the emergence stage. The manuscript discussed this explicitly in relation to the self-determination norm. Specifically, it referenced the contrasting understandings of the norm that the United States and the USSR advanced. For the norm to cross the tipping point and cascade, entrepreneurs must reach some level of agreement over its meaning with which a broader audience can engage. This meaning can result in a political agreement or a legal instrument set out in broad language. Such was the case of both the prohibition of torture and the right to self-determination. In the first case, consensus over the meaning of the emerging norm was limited to prohibiting the practice without a clear definition of what constituted torture. In the second case, entrepreneurs agreed on the norm in principle but attributed different scopes to it. In the absence of a basic shared understanding of the meaning of the norm, pro status quo actors, such as norm antipreneurs, are likely to prevail. One of the reasons is that without it both advocacy and institutionalisation are unfeasible. In terms of the prohibition of torture, agreement on the fundamental dignity of the individual and the incompatibility of inflicting pain as an instrument of justice with states’ duty to protect their citizens provided the necessary foundation for the norm to cascade.