Introduction

The Round TableFootnote 1 is an authentic democratic form of constitution making, to be placed side by side with the convention pioneered in the United States in the 1780s, and the constituent assembly made classical if not actually invented in France in 1789 and 1793. I have in mind a multi-stage set of procedures, with free elections in the middle (rather than the initial stage), generally with an interim constitution (or functional equivalent) drafted by a key (but non-sovereign) instance, a negotiating forum. The latter was called, first in Poland in 1989, a round table, and it is from this new institution that I take the name of the whole paradigm. In my terminology the Round Table form is post-(organ) sovereign in that no instance, institution or person can claim to fully embody the will of ‘the people’.

The South African constitutional process in the 1990s paradigmatically exemplifies the Round Table form of constitution making.Footnote 2 This processFootnote 3 was composed of two major stages, with a democratic election between them, involving the making of two constitutions, and with a multi-party negotiating forumFootnote 4 or round table, a constitutional assembly and a constitutional court as its three main institutional agents. The South African process was not unprecedented. It has been to various extents anticipated by constitution makers in Spain in the 1970s, and several Central and East European countries in 1989 and 1990, but the South African process to date represents the most developed and complete instantiation of the Round Table form.

The new form is a type of constitution making that allows us to understand the meaning and the deficiencies of the forerunners. In the following I will argue that it is normatively (and not only often strategically) superior to these earlier forms. Nevertheless I will note its path-determined aspects, and the difficulty of applying the complete paradigm where forces of an old order have (or assume to have) the legitimacy to carry out full constitutional reform, or where forces of the new can succeed in carrying out a revolutionary rupture. Yet even in these cases, I will argue that the principles and some of the structural elements of the new paradigm can be the key to solving the almost inevitable legitimacy problems of reform and revolution.

History of forms: Convention, Constituent Assembly and Round Table

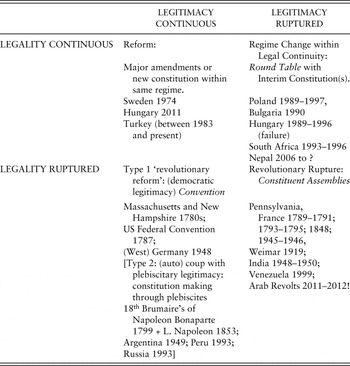

Four forms of original, democratic constitution-making can be organized around the reform and revolution polarity, if we reconstruct it around two axes, legality and legitimacy, and rupture and continuity.Footnote 5 We can then map out four possibilities, to which typologically four types of democratic change of constitutions correspond. Reform (legality and legitimacy both continuous) would have its typical form of change according to the established rules of revision or amendment rules. Revolutions (both old legality and legitimacy ruptured) as already in Pennsylvania during the American Revolution, and then in France in 1789 and 1792 rely on sovereign constituent assemblies. These forms are fairly well known, though the concept of revolution in particular has been generally understood differently than here. The role of the popular factor has been stressed, though it is questionable whether many ‘revolutions’ were carried out by anything more than minorities. There has been also a tendency to define revolution in normatively progressive terms, a temptation that I will avoid here. Thus counter-revolutions are also revolutions as I understand them. On the other hand, while the presence of coups in revolutions has been almost an historical constant, as against Hans Kelsen, I do not identify coups and revolutions. This identification happens in his case because he identifies legality and legitimacy and their ruptures.Footnote 6 More importantly, in the scheme offered here I get two additional, equally pure types: continuous legitimacy, with legal rupture, to which the American convention form, presupposing republican forms of government, corresponds.Footnote 7 Ackerman usefully called this revolutionary reform.Footnote 8 Finally, in the context of a full break or breakdown of legitimacy but continuous legality we get the special type of regime change within legal continuity, associated with the Round Table form.

Table 1. Major types of democratic transition with forms of constitution making

Table 1 below can use some commentary. First as I show, there can be a process that starts one way and turns into another. Several Latin American cases, like Argentina 1949 and Venezuela more recently start as conventions, and wind up as plebiscitary coups or as sovereign constituent assemblies (or their combination). ReformFootnote 9 can fail and turn into Round Table, as in most relevant cases here, but also into revolutionary constituent processes as in India and other post-colonial cases.Footnote 10 Even without prior failure, reformers are free to adopt constitution-making patterns presupposing extraordinary politics and institutions. They must in that case weigh the risks of a process they may not control, against the needs of heightened legitimacy.Footnote 11 Conversely in a revolution, e.g. the externally imposed one in Iraq, a non-revolutionary form of constitution making can be adopted. Second, classification cannot be absolutely neat because one major element can be missing from a form that nevertheless is classified with others that are largely similar. For example the conventions of Massachusetts and New Hampshire were legally established (there was no legal rupture) and so were some Latin American cases, where this was provided for by the amendment rules. (Other Latin American cases involve later ruptures, leading to the plebiscitary or revolutionary types.) Conversely, there was a legal break in Nepal whose incomplete process in other respects belongs to the Round Table form. Finally, the prototypic post-sovereign case of Spain did not start with the creation of a round table forum, and its interim rules were established from above and confirmed by a referendum.

Here I will concentrate on the three democratic forms involving generally discontinuity in one of the two domains, having to do with original constitution making capable of producing new regimes. I will to an extent neglect coups and self-coups because I do not regard plebiscitary legitimation as democratic at all, and will mention these only where they are results of the failure of conventions and constituent assemblies. (They can also become relevant with the failure of reform!) However, a historical analysis cannot avoid also touching on the model of reform. As already implied, uncannily, the various forms tend to originate from one another. The Convention form, as finalized by the American Federal Convention, grew out of reform.Footnote 12 As in the case of several state conventions,Footnote 13 its project originally was only a large-scale reform of an existing system, constitutionalized by a treaty, the Articles of Confederation. The framers, and eventually the states violated that project and produced much more radical change within an established structure of the legitimacy of the states. The drafting Convention that could only recommend to ratifying conventions in the states was the main instrument of the legal breaks within a generally intact overall legal and institutional system. This Convention was doubly differentiated from legislative and other powers; it exercised no other powers than constitution making, with no other institution having constituent powers till the moment of ratification.

While it may be an exaggeration to say that the Constituent Assembly grew simply out of the Convention, this is more or less what directly happened in Pennsylvania in 1776 when the dual power of two assemblies, the convention and the regular legislature could not be stabilized.Footnote 14 The result was a sovereign constituent assembly, still under the name convention, along with a radical democratic constitution. More importantly for the future, the American model of the Federal Convention failed in France in 1789 in spite of its significant influence on theory. Important authors and leaders wrote on the American constitutions, including the convention form, and the most sophisticated (Sieyès, Condorcet) repeatedly expressed their preference for ‘double differentiation’, for electing an extra-ordinary convention for the sole purpose of constitution making with no other powers in the state. Under French conditions this proved impossible: in 1789 because of the existence of a society of orders and an estates assembly based on it, and in 1792 because of a second revolution that swept away the powers of the elected Legislative Assembly. The practice produced sovereign constituent assemblies, and it is this practice that became canonical for democratic and radical theory, especially because the result in 1793 was the never-instituted democratic constitution. But the association of the second such body, the Convention nationale with revolutionary dictatorship and the Reign of Terror meant that others, mainly liberal democrats, continued to look back to the 1789 prototype, the Assemblée constituante, with its liberal if barely successful 1791 Constitution. Thus the name constituent assembly survived, and the most important difference between the two forerunners, whether the constituent assembly should offer its product for popular ratification, remained forever unresolved.

The Round Table form is generally the offspring of two parents: the reformist and revolutionary one. Without many exceptions,Footnote 15 in most historical contexts an old regime in power tries but fails to enact successful comprehensive reforms on its own. Everywhere there is also a revolutionary or radical democratic scenario in the wings demanding a democratically elected constituent assembly, not making clear how without taking power it can answer Lenin’s significant objection from 1905, namely that the old regime would still dominate such elections. (The Hungarian democratic opposition rejected calling for a constituent assembly for this reason!) In any case for a variety of reasons, with the exception of Iran, revolutionary power has not been available from the mid-1970s to 1990s,Footnote 16 or better still remained a mere potentiality more feared apparently by the old regimes than trusted by its agents, who either did not believe the power existed, or were wary of using it even if it were available. This was true in South Africa too, significantly because this country did have a powerful revolutionary movement. Yet the Codesa and the Multi-Party Negotiating Forum rounds (and even the previous ‘talks about talks’) emerged from a similar constellations as the other Round Tables: The impossibility for old regime actors to save their system through mere reform, and the inability of oppositional, even revolutionary movements to carry out a revolution. The Round Table form, born of this strategic constellation, gives to the reformers, a negotiated first-phase process in which they could attain guarantees enshrined in an interim constitution. The very same form provides radical democratic forces with a freely elected constitutional assembly that unlike the American state ratifying conventions of 1787–1788 gets to re-draft the constitution proposed by unelected instances.

The strategic reasons for moving from form to form are clear. Following the reformist process, namely the rules of the Articles of Confederation, could not have achieved the more centralized system many of the large American states wanted. They needed to break the rules, and the doubly used institution of conventions, associated with popular government, legitimated these breaks.Footnote 17 At the same time, it should be noted, anything like the revolutionary constituent assembly formula, known from the Pennsylvania prototype, would have been not only unacceptable to the majority of the delegates, politically the Federal Convention did not have the power to accomplish such radical self-conversion. The one related proposal, to have ratification of the draft only by an elected national convention (by Gouverneur Morris) was not even seconded.Footnote 18 As to the French Constituent Assemblies, however attractive American precedents may have been to them, the leading revolutionaries and constitutional experts had no wish to share power with aristocratic institutions of the past, even temporarily. Even the king, left in place, was deprived of his veto over the constitution to be made. But normative or theoretical justification was not missing in this case either. The move to an all-powerful constituent assembly was accomplished in 1789 in the name of a unitary notion of popular sovereignty embodied in a single assembly with the plenitude of power. In America popular sovereignty played a role too, but in an antinomic form, with the idea of the people alternately understood in national and ‘federal’ terms.Footnote 19 Here the notion of sovereignty embodied in a single instance had to be and was absent.Footnote 20 As to the second French Revolution in 1792, it was the power of a popular revolution rooted in Paris that made moderate republicans like Condorcet, committed to double differentiation, accept the destruction of the freely elected legislature, again in the name of unitary popular sovereignty. This time, the protagonists successfully argued that a genuinely democratic constitution could only be produced by an assembly whose election was fully democratic, and whose authenticity would be checked by popular referendum. This hope was fulfilled most of all by Condorcet’s sophisticated 1793 draft, and even by the Constitution of 1793, but not the Convention nationale’s dictatorship that suspended the latter.

Finally, from 1989 to the 1990s, from Poland to South Africa, it was the combination of the collapse of the legitimacy of old regimes and the insufficient power of oppositions that led to the new formula, with its first stage negotiated at Round Tables. Most oppositions would have preferred not to negotiate with previous oppressors, but for strategic reasons they all had to. At the same time many, especially in Central and East Europe, did not wish to adopt any revolutionary perspective, given the revolutionary ideologies of the old regimes. Thus the new model is linked to a post-revolutionary consciousness, if not yet an ideology, centering in civil society rather than the state. While popular sovereignty in the form of majority rule still played an important role, a greater one in South Africa than elsewhere, because the nature of the earlier apartheid regime made consociational arrangements suspicious, this sovereignty was no longer conceived as embodied in a single institution or agent as in most revolutions. The majority would rule through many institutions, including the Constitutional Court. Equally, post-revolutionary ideas of reconciliation, between former enemies representing important parts of the population, and rule of law applied to the process as well as the result of constitution making were important.

The historical influence of all these forms is undeniable. The American form has influenced French development, but in a paradoxical manner. Unused in the practice of original constitution making, despite the term Convention nationale, the convention formula involving double differentiation, found its way into French amendment rules that in turn were almost never used,Footnote 21 similarly to the (national) convention in the U.S. article V. In the U.S. only the states were to have constitutional conventions, doubly differentiated as the theory required, and they did so frequently, under a stable federal order.Footnote 22 That order itself, the Federal Constitution, formally speaking, had only – rather few – partial amendments since 1787, while the 15 or so French Constitutions emerged through coups, revolutions, and semi-legal revisions of the revision, but never through convention or assembly of revision formulas. Latin American history with its many constitutions is generally similar to the French pattern. Though U.S. institutions, including at times the convention, were widely imitated, the actual process of alteration was through coups, self-coups and revolutions using plebiscitary imposition or – in name at least – sovereign assemblies. In the older case of Argentina under Peron, and the recent case of Venezuela under Chavez, the convention formula under the name constituent assembly (‘constituyente’) was used, but broke down and was turned into that of sovereign constituent assemblies controlled by plebiscitary presidents.Footnote 23 Yet there is a single, late success story for the convention model. Under a different name, the Parliamentary Council at Chiemsee that drafted the highly successful German Federal Basic Law and sent its product to ratification to the states came close to the American Federal Convention type.Footnote 24 Interestingly, here history moved in reverse direction. To German liberals and democrats, the Constituent Assembly was the type that would have been most suitable to express the sovereignty of the political community. In the context of occupation, and division they deemed producing a constitution by a constituent assembly as inappropriate. The Grundgesetz was thus meant as a provisional constitution, a promise unredeemed in the 1990s!

That last example too shows that the sovereign constituent assembly formula has been hegemonic for democratic constitution-making, producing notable successes like India’s constitution, total failures like Russia in 1918, but also the short-lived constitutions of Weimar and the Fourth French Republic, and many, many cases in between. Very often, as Lenin anticipated, and here Latin America (and Africa) with its many constitutions is again an important case in point, the constituent assembly turned out to be a mere instrument for whatever force was able to convene it. Even when this does not happen, the result is open to the charge as in the cases of Weimar and the Fourth Republic. Finally, the Round Table based form has now a real history, with successes and failures. Leaving out the ‘miracle’ of Spain that had no initial negotiations, Poland, Bulgaria, South Africa count as the successes with workable final constitutions; the German Democratic Republic, and Czechoslovakia were complete failures, and Hungary is a semi-failure (I used to say partial success!Footnote 25) whose outcome is still in doubt. The application of the form in the externally imposed revolution of Iraq was probably a failure that could still be perhaps redeemed,Footnote 26 and we still do not know the outcome for Nepal where it was applied after a legal break.

On the purely empirical levelFootnote 27 then it would be very difficult if not impossible to determine the superiority of any of the three forms that seem to be adopted always for situated, strategic reasons first of all. I turn therefore to a brief set of structural and normative comparisons.

Comparing and debating the three forms

Analytically it is relatively easy to depict the difference among the three great democratic types, and very schematically I would emphasize seven dimensions in which there are differences among them. This leads to Table 2 (see page 13).

Table 2. Forms of democratic constitution-making and their elements

Again commentary may be helpful on some of these points, where the table is not self-explanatory. I use the term double differentiation, as introduced by Claude Klein,Footnote 28 in the path of Carré de Malberg, to indicate that the (generally) earlier legislature that stays in place does not engage in constitution making, while the main assembly or assemblies involved in making the constitution assume no other power in the state. Differentiation is single where ordinary legislatures do not make the constitution, but the constituent assembly assumes legislative powers (often in the form of decree power) and often, through its committees, executive ones. When the process involves two main stages of drafting, differentiation can take the double form in one stage and the single form in the other. Since a prior legislative assembly in this later case is undemocratically put together, it is unlikely that it will retain its powers under a freely elected constitutional assembly. This latter combination of two doubly differentiated stages was to be sure advocated in Iraq by the American CPA, but collapsed with the abandonment of a co-opted legislative body.Footnote 29

As to the role of the final relevant body in the process (assembly or electorate) I call it passive when it can only ratify or reject the whole constitutional draft, and active when it can either modify it or produce a new one. Here levels of passivity are not the same. Referenda, though important in terms of their ‘shadow’ on the previous process are entirely passive. Ratifying conventions à la americaine are relatively active, since they can and did suggest important amendments that the subsequent amending process could and did take very seriously. The Bill of Rights was the American result. I do not exclude finally some kind of combinations of referenda and ratifying conventions, as suggested by Ackerman and Fishkin (‘deliberation day’), though these have historical examples or analogies only in the township ratification processes in revolutionary America.

The place of sovereignty in the model is less a descriptive than a theoretical issue. Thus it belongs mostly to the normative differences among the models. Here I would only like to say that the concepts of sovereignty of the actors and my assignment of a type may be different. The actors may claim to have embodied popular sovereignty not only, and necessarily, in the revolutionary constituent assemblies, but also in the cases of the Convention and the Round Table, and express it in preambles. In my view, both the federalist problem of duality, and the multi-stage process make such a claim problematic. At times this is recognized, and it is admitted that authority is one thing, ‘the people spontaneously and universally moving toward their object’ is quite another. (Madison in Federalist 40) The admission of impossibility in the latter case bifurcates factual and legal meaning of sovereign powers on the one side, and denies that the people can (or should) make constitutions in their collective or corporate that is an embodied capacity.Footnote 30

This exclusion of embodiment leads to significant normative differences among Convention, Constituent Assembly and Round Table that are however difficult to evaluate. I will try through three two-by-two juxtapositions:

Convention vs Constituent Assembly

The critical comparison, to my knowledge, focusing on double differentiation, has been attempted only by French writers during and after the Revolution.Footnote 31 From the beginning, the fundamental argument in defense of conventions, based on the separation of powers, has been that the always dangerous legislative power should not be allowed to transform its own parameters, and conversely, a constituent power should not become too closely identified with legislation if it is to establish a workable separation of powers. The argument for the Convention is thus based on a distinction between constituent and constituted power but in a version ultimately derived from the ideas of Montesquieu.Footnote 32 At least this is the way the case was argued in France, notably by Sieyès. In America itself the influence of Locke was perhaps more important, especially his avoidance of the term sovereignty when distinguishing the original and by strong implication constituent power of the people, and the legislative power of government. With lots of caveats having to do with the problem of representation, the defenders of the constituent assembly see the same distinction in terms of Rousseau who in fact did not differentiate the legislative and constituent powers.Footnote 33 The key is popular sovereignty, here expressed through electoral majorities. A constituent assembly elected by a majority supposedly expresses and embodies the will of the sovereign people, and therefore cannot, like a convention, share power with an instance elected at a previous time. Legislative power is also a supreme power, and if defined in terms of sovereignty there cannot be two supreme powers in the state. The defenders of the convention model can respond with a different notion of popular or national sovereignty, one that cannot be embodied in a single person (king) or institution (assembly) or group (the Parisian popular insurrection) without usurpation. From this point of view a single-stage, single-assembly model as in France runs the danger of just such a usurpation. Not only double differentiation then, but the multi-stage character of the story of the Federal Convention involving at least five instances each of which has an influence on the draft (the Convention, Congress, state legislatures, the electorate of the states and freely elected state conventions) keeps the model from usurpation. Finally, Carl Schmitt has referred to constitution making in the form practiced in France in 1789 and 1793 as well as Weimar as sovereign dictatorship.Footnote 34 To him being in the state of nature, liberated from all prior constraints including the separation of powers was central. While it is not entirely clear whether the dictatorship is exercised by the assemblies or by provisional, revolutionary governments that control them, and whether self-limitation can effectively block the road to what is ordinarily considered arbitrary dictatorial rule, the elective affinity (not = identity) of revolutionary constituent assemblies to dictatorship is thereby demonstrated.Footnote 35 There is no such elective affinity for conventions that in spite of the possibility of some very specific illegalities operate under established rule of law systems whose constitutions they replace, without full legal rupture.

Constituent Assembly and Round Table

The debate between the two models occurs in two dimensions: dictatorship vs democracy, and radicalism vs conservatism. It obviously cannot be denied that the revolutionary constituent assembly is capable of a more radical break with the past, if one focuses on the identity of the rulers and the direct beneficiaries of rule.Footnote 36 An agreement with the latter reduces the extent of the break. This is a serious problem from many points of view,Footnote 37 all having to do the ‘conversion’ or preservation of illegitimate forms of earlier power. Nevertheless, the two-stage formula does allow the constitutional assembly of the second stage to accomplish a change of regimes if that did not already occur in the negotiated phase. The price of the formula will be reform rather than revolution in some important domains, given the political focus of the regime change, mainly in the socio-economic sphere.

It is meanwhile questionable whether revolution ever realized its social economic goals of equality and justice, rather than generating alternative systems of inequality and injustice. On a constitutional level, undoubtedly the fact that the new regime does not have to be designed together with those attached to an old form of life is in part responsible. Important population segments politically opposed to the old regime, even the majority, can be therefore entirely left out of the construction of the new that will then make no concessions to conservative life forms. The religious in France and the peasantry in Russia are two salient examples, the protagonists of two civil wars. The result is almost always resistance and new forms of repression, often long term. In the Soviet Union, the war against the peasantry (‘the kulaks’) and Stalinism is the final consequence of revolution, and should not be seen as a Thermidor.

Thus, it is in the dimension of democracy and dictatorship that the Round Table formula has its obvious superiority. Since the transition in the case of both types, revolution and legal regime change, is invariably from authoritarian regimes, here constitutional democracy represents the more fundamental break,Footnote 38 not the establishment of a new dictatorship. Revolutionary constitution making, in spite of its democratic appearance in the constituent assembly form, tends to exercise dictatorship as Marx in 1848, Lenin and Schmitt equally maintained, and produces legitimacy problems that are difficult to resolve without authoritarian reversion. The Round Table form avoids sovereign dictatorship, and, as we will see produces a variety of plausible answers in each of its stages to the problem of legitimation.

Convention and Round TableFootnote 39

It is on the question of sovereignty, that the Round Table model can fully share the logic of the American Convention, without the historical attachment to the concept of sovereignty or the antinomy of nationalism-federalism. Having adopted the idea of the second ‘convention’ that formally speaking lost in AmericaFootnote 40 the multi-stage model here has really come into its own. In the fully developed South African case we see an equal number of relevant actors: the RT (MPNF), the old parliament, the electorate, the constitutional assembly and the Constitutional Court.Footnote 41 More importantly, in comparison to the Convention type with its formally oneFootnote 42 drafting agent, three of these agencies play an important role in drafting and design, and none of them can claim fully sovereign or unlimited status.

It is important to stress the transformation of the problem of sovereignty in the Round Table model. The American understanding of constitution making, as the preamble to the Constitution shows, was in the name of the sovereign people. In the conflict between federal and national conceptions it was difficult to find the identity of the body fully representing the people, the body where their representatives met that did all the drafting, the Federal Convention, or the bodies that had the final word, the state conventions. In this sense the sovereignty of the whole was not fully embodied in any instance even on the level of constitution making, and Hannah Arendt’s judgment concerning the banishment of the (organ) sovereign can be upheld.Footnote 43 Yet the appeal to the sovereign as the author of the constitution meant that organ sovereignty could not be reliably banished from the American scene.Footnote 44 In different historical contexts, especially moments of crisis as we see from Ackerman’s conception, and when transported elsewhere, to more centralized settings, the American conception allows the revival of the idea that a constitution should be the work of a unified popular sovereign, represented (indeed united) by an organ of the state. The multi-stage Round Table formula that divides the work of discussion, drafting and enactment goes a step further in the direction where organ sovereignty is banished, when the place of the king really becomes an empty place.Footnote 45

The whole history of the American model of constitution making, and the difficulty of applying it elsewhere, suggests exceptionalism that is by no means escaped by Hannah Arendt’s brilliant analysis. Condorcet already noted the problem, calling the American transition one from a free to a more free constitution, and, as he recognized in the case of France, generally such is not the context of original constitution making.Footnote 46 In most places well functioning republican institutions are not available for the purposes of double differentiation. Moreover, as Carl Schmitt noted as well, in America the making of a new type of federation and constitution making coincided, more or less. This not only made impossible, as Schmitt stressed, the clear decision of the constituent power about the form of the state, but also provided stabilizing framework for multiple institutions that elsewhere had a tendency of reverting to a duality of power. Thus the model has always had the greatest chance of success where the relevant individual states were embedded in larger federationsFootnote 47 or where the creation off federal institutions occurred in the context of stable unit constitutions.Footnote 48

The Round Table process of constitution making not only makes more explicit the critique of sovereignty latent in the American convention model, but makes the achievement of overcoming organ sovereignty in constitution making less exceptional. Neither pre-existing republics nor federations of any kind are required, and there is no need to create federal states when using the model.Footnote 49 At the very least it should be said that the ability to institute democratizing, and in its second stage, democratic process of constitution making regulated by constitutional rules where there is neither democracy nor constitutionalism dramatically reduces the exceptional nature of the circumstances where post-(organ) sovereign conceptions can apply. This means that the circle of authoritarian rule and dictatorship can be broken by a method that does not itself risk a new authoritarian form.

But this is not yet a normative advantage over the Convention form. That superiority I see in terms of the already stated objection at the Federal Convention, renewed by the Anti-Federalists, that it is impermissible to give the last enacting instance, representing the ‘the people’ a simple yes or no choice in the case of complex packages, in other words not to allow the elected bodies to make their positive constitutional inputs. Extended, this means that the societal discussion in which for example the Federalist (and Anti-Federalist) Papers were one among many important publications should have been allowed to have an effect on the outcome, beyond getting the assent of people who preferred more things in document than they rejected. The second convention idea, linked to that of an interim constitution, was an important one from the point of view of democratic theory, whatever the reasons for its failure at the time. In the new model, the interim constitution and the public discussion around it and the elections for the constitutional assembly provide the context for making many new inputs into the final document. Thus there is both learning with respect to the convention model, and the institutionalization of learning within the new model. Footnote 50 The constitutional assembly has a chance to make fruitful the results of the latter learning, through its own discussions, the works of its committees, the inputs of external participants, and, uniquely but correctly in South Africa, the certification process, and relevant re-drafting. All this represents tremendous democratic gains over the passive ratification in referenda that become unnecessary for the new model.Footnote 51

Finally I should consider a supposed normative disadvantage of the Round Table: the initial drafters are not elected, but co-opted. While free, competitive elections did not occur in the case of early historical prototypes of constituent assembly and conventions, these forms definitely allow and now generally entail ‘initial’ free elections. With respect to the convention model, the path-determined aspect (discussed below) of these models produces the difference that can involve two separate elections in the case of the Convention but only one for the Round Table. Conscious of the legitimation problem involved, most protagonists of Round Tables try to generate compensating forms of legitimacy. It is an empirical question to what extent they succeed, but as the South African case shows high level of representation can be their combined result. With respect to the elected constituent assembly, that is possible also on the same historical path as the Round Table, with an authoritarian regime as the initial starting point, it is important to emphasize first, that in both types there is only one election, and the question is whether it is superior to have that election in the very beginning or the middle of the process. Second, in the case of constituent assemblies (unless aspects of the negotiations characteristic of the Round Table are adopted) the rules of election will be imposed by either the old regime (as Lenin feared in 1905) or by the holders of revolutionary power (as he imagined, with good reasons but lack of success in 1917–1918). This produces a legitimacy problem for the outcome, normatively and potentially empirically as well. The choice then is either co-opted representation with subsequent non-imposed electoral rules, or imposed rules with democratic representation.Footnote 52 Note again, that elections in the Round Table model do take place, for the second, definitive drafting body. It is thus arguableFootnote 53 that an imposed stage in the case of constituent assemblies replaces a negotiated stage in the Round Table, while in both models democratic elections happen only after such an initial stage. Thus in respect to electoral legitimacy the models are either equal from a normative point of view, or (as I believe) the Round Table form is superior in this dimension as well.

The synthetic nature of the new model

The fact that that the Round Table realizes the lost aspirations of some important architects of both the convention and constituent assembly models already indicates its synthetic nature. Of course the synthesis I have in mind was entirely unintended: the participants as far as I can tell paid no attention to the convention form, and, on the democratic side abandoned the constituent assembly formula first and foremost for strategic reasons given the historical constraints. Thus what follows, has a reconstructive nature, focusing on structural and normative features rarely entirely clear to participants.

Yet, it has been rightly remarked that the round table forum is something like a convention (Elster), and one could equally say that the constitutional assembly paired with it resembles in some respects the constituent assembly of the classical revolutionary model. As to the first point, neither round table forum nor a convention, at least in the cases of the 1780s, ‘are known’ to the previous constitutions.Footnote 54 Both only recommend, as far as the final constitution is concerned,Footnote 55 but do so in a way that becomes at least a large part of that constitution. The differences should be noted as well. As already noted the Round Table form does not have initial electoral legitimacy, even one with a long chain like the Federal Convention whose members were delegated by elected state legislatures. Of course other conventions, in the states were elected. By its nature, the round table institution cannot be an elected body, since its task is to establish for the first time the rules by which free and fair elections can take place. Its legitimacy problems are greater, a point easily lost in South Africa where the charismatic ANC leadership had such great prestige among the majority of the population. And this leads to the next difference already noted: the Round Table’s constitution is (or should be) only an interim one, and it leads to very serious legitimacy problems where, as in Hungary, it tended to become permanent before its recent replacement.Footnote 56 The convention produces a final constitution, one that the ratifying instances however can only accept or reject.

The similarity of the constitutional and constituent assemblies is also significant. Both are democratically elected, at least after the first French prototype. Neither is doubly differentiated. It is true that the South African Constitutional Assembly was technically the two chambers of parliament meeting together, while separately they could meet as a regular legislature. But this is a very low degree of double differentiation, anticipated in part by the Indian Constituent Assembly, meeting some time under one set of rules as parliament, and other times, under other rules, as the constituent body.

Nevertheless, the differences, already mentioned are equally important. I already discussed the problem of elections under the two models, and argued that the Round Table is not inferior on this level, in spite of the supposedly initial free elections that take place under most constituent assemblies. More important in my view is that after elections have taken place, the constitutional assembly of the Round Table model, is not sovereign, operates under constitutional rules not under its own disposition, and is accountable for adhering to these rules (and in South Africa: to substantive principles) to another body from which it is indeed sharply differentiated: the Constitutional Court. While the latter subordination of the constituant to the constitué has been clearly practiced only in South Africa, in the case of procedural violations at least of amendment rules a similar logic would necessarily have come into play in most other Round Table countries.Footnote 57 Thus the Constitutional Court, created by the interim constitutions of this model, becomes a substitute for the double differentiation that cannot be accomplished between the legislative and constituent powers.Footnote 58

As a synthetic, multi-stage form, the Round Table combines many of the advantages, especially the creative aspects of conventions and constituent assemblies, but escaping the dangers of both that are inherent in their remaining links to organ sovereignty. It is this synthetic character that allows the form to make more radical change in regimes than the American convention form, without the danger of revolutionary dictatorship, inherent in constituent assemblies. Like the convention, but much more consistently, it replaces a model of sovereign constitution-making with an affinity for dictatorship, with another where the will of the people is expressed through a variety of instances, none of whom can claim full identity with or embodiment of the popular sovereign. But, like the constituent assembly, it culminates in a stage of democratic constitution-making, where the elected instance really makes a new constitution. And all these elements are linked together by a new type of constitutional framework, enshrined in an enforceable interim constitution. But is this model itself of universal significance, or is it one simply belonging to a particular set of paths?

Path determinacy of Round Table form and its apparent inapplicability to reform and revolution

So far we have had only examples of the use of the Round Table form under collapsing dictatorships, and uniquely under the apartheid state that was indeed a dictatorship to the majority of the South African population. The Round Table involving negotiations with a party that controls the existing machinery of government would not easily find its relevance where the state is already in the hands of freely elected officials, or where a multiplicity of such states wishes to form a new overarching constitution. Moreover, even under dictatorships, a revolutionary force that has the full power to overthrow a dictatorship is not likely to enter into negotiations with its defenders or beneficiaries.Footnote 59 So in the case of revolution, reform and constitutional treaty-making or contract the model does not seem to be applicable in spite of its synthetic and attractive character.

Let me distinguish, first, as I have in the past, between the model and its principles, and this time also, the model, and its parts. The nature of the Round Table, born in the legitimation crisis of old regimes, yet involving the presence of its actors in negotiations, raised the problem of legitimacy in particularly serious ways. In this it is significantly different from the other democratic approaches here, that paradoxically do not raise the problem of legitimacy because they are initially much more sure of having it. To start with reform, this approach can rely on a strong sense of legal rational authority that would be available at least under a rule of law regime. Indeed, the reason why dictatorships find it so hard to reform once their charismatic or plebiscitary or ideological legitimacy fails is because they cannot rely on legal legitimacy. Yet, the legal legitimacy of reform, as Carl Schmitt has tirelessly argued, and the Indian Supreme Court demonstrated in practice, does not reach so far as to allow mere incumbents to replace a constitution, or even alter its ‘basic structure’. When there is such an attempt, as Mrs Gandhi found out, the result can be a long-term constitutional crisis, and a possible reversion to authoritarianism using legal resources of constitutions.Footnote 60

Revolutions can gain their legitimacy from a variety of sources, ideological and personalistic, but one crucial dimension is the achievement of liberation from hated old regimes that for a time unites different segments of the population around liberators. This is why in the period of construction, Arendt’s ‘constitution’ they develop legitimacy problems and consequently repressive substitutes for legitimacy: the consensus of liberation is not easy to attain through a program of new construction, to the extent a revolutionary elite imposes it.

Finally, revolutionary reforms of the American type, that are linked to the convention type, are possible only as the legitimacy of some important inherited institutions is presupposed throughout the process. When the new system produces a fundamental alteration in their political status, as in the Federalist period in the U.S., this regime too can have a legitimacy crisis linked to an authoritarian phase.

As against all these types, the Round Table multi-stage method begins with the depleted legitimacy reserves of failed reform.Footnote 61 The thin legality on which both regime and opposition take their stand is enough to functionally co-ordinate their expectations. It is not enough to legitimate deals and compromises, especially since the work of the negotiated instance was supposed to bind the work of the elected one. Neither the former old regime reformers nor the new oppositional forces have strictly speaking democratic legitimacy. This too is especially important, because it drives participants to try to solve the universal problem that a system cannot begin by its own rules, or: where there is no democracy one cannot begin democratically.Footnote 62 The designers of Round Tables have been thus especially creative in finding new sources of legitimacy: pluralistic inclusion as wide as possible, decision making by consensus as broad as possible, openness to public scrutiny or inputs, scrupulous adherence to the letter of agreements or to the new, emerging legality, democratic elections as soon as possible, under relatively passive rules, and attempt to operate under an empirical veil of ignorance regarding outcomes (or: avoidance of self-serving rules by majorities!) are the main alternatives generated. When there is charismatic leadership available this helps as well, but it is relatively rare and cannot be engineered.

There is little question concerning the transferability of these principles. We find many anticipations in American and French models, and even more, echoes and influences in all that occurs afterwards, for example the Convention for the Future of Europe scrupulously interested in the public character of the proceedings. By having to face the problem of legitimacy squarely, the lesson is being offered to future reformers and revolutionaries who should be less confident about the reach of their authority to make constitutions on the bases of past experience.

But constitutional learning can take more from the new paradigm. Starting with the recognition, that it is specifically the round table institution that is path determined, the multi-stage character of the new process with an active but not sovereign democratic body as its final stage can have a much wider application.

What I would like to argue is that first and foremost, it is learning from the principles that is important.Footnote 63 Even if every single aspect of the new method were taken over, this would be without value if the normative standards were neglected. Secondly, I would also like to show, that paying attention to the principles may be insufficient without at least some learning from the institutional design of the new paradigm, without necessarily imitating the whole scheme. Instead of making an abstract case for this conclusion, I would like to illustrate it with three cases.

Revolution and the pathological adoption of the complete model: Iraq

The case of Iraq shows that even in a revolutionary regime transformation, the new model could be adopted. After having studied the case carefully, I do not think it was adoption amidst conditions of a complete legal rupture that made this a pathological case.Footnote 64 Of course, it was under American and international pressure that those committed to total transformation were forced into this scheme,Footnote 65 that curiously enough copied all the main stages of the developed model: multi-party negotiations, interim constitution, free elections and non-sovereign constitutional assembly. Such an external role is admittedly a serious problem, but I think it could have been compensated for if the main foreign force allowed the process to develop according to its own proper normative principles. That did not happen. The main principles were violated, even as the formal elements were adhered to. The principles of broadest possible inclusion, equal participation and consensual decision-making were violated in the first stage. And that of democratic decision-making in the constitutional assembly, the all-important second drafting instance were lost in the second, replaced by an extremely dubious referendum. Overall adherence to legality was violated repeatedly. Public participation and visibility were never organized or even allowed. Given the low level of legitimacy of the first, exclusionary stage, the binding of the second to its results through very difficult amendment and ratification rules was unacceptable. This significantly interfered with the learning potential built into the model, and in fact the second constitution turned out to be less effective and viable than the interim one. The lesson is clear: the model will only work if those of its elements that are applied are used in a fully consistent manner, and this cannot happen without the main principles of inclusion, and consensus in the first stage, drafting by those fully responsible to a democratic body in the second stage, and legality and publicity in both stages.

Refurbishing reform with legitimacy problems: Turkey

Since 2007, the AKP led government in Turkey has been trying to transform the inherited constitution, imposed by the military, and reformed repeatedly through parliamentary consensus, through majoritarian reform process enabled by the Constitution’s amendment rule and a highly disproportional electoral system. Not only has this raised serious problems of legitimacy, but it also ran into Constitutional Court opposition based on three eternity clauses of the Constitution. The government recently responded to this limitation, by a court-packing project that was sustained both by a Constitutional Court decision and a subsequent referendum. In my opinion a far better alternative would have been the introduction or reintroduction of a consensual, public and participatory process of new constitution-making linked to the principles here discussed. Structurally, one excellent way of doing this (hardly the only one) would have been to elect, without the undemocratic 10% threshold a highly representative advisory body (convention, conference, whatever) that would make its recommendation to a parliament elected at the same time, itself capable of making further changes in the draft.Footnote 66 This idea is linked to both convention and round table models, but resembles the latter because of its active two assembly scheme. Here some of the principles of the new model, namely inclusion and consensus are emphasized, and they are linked to a new recommending assembly that is to be created. While from the point of view of the new paradigm this represents a partial adoption of its elements and principles, this is so because a democratically elected assembly is already in place, along with a rule of law constitution. Thus one does not need a Round Table or an interim constitution for such refurbished reformist scenario. It remains open, whether after the elections of 2011 that deprived the AKP (Justice and Development Party) of its constitution-amending majorities (not only for the two-thirds but also for the three-fifths option involving referenda) some adjustment of the purely majoritarian reform path will be made.

Re-structuring a federation: the EUFootnote 67

The idea of the Convention for the Future of Europe was not only to establish a more constitutional outcome, formally and substantively, than by the treaties of the past, but to produce greater legitimacy for such a constitutional treaty. This was done by very much relying on principles of public openness, participation and consensual decision making – popularized by the experiments of the 1990s. In light of past experience, a Convention form seemed very appropriate to try to create a closer union among members of an already existing federation. The method of submission to a powerful Intergovernmental Conference, and then to the national referenda of at least nine states rechanneled the process into the old treaty-making mode, that wound up exposing the project to failure through the negative votes of various opponents more opposed to one another than to the constitutional treaty itself. The Lisbon Treaty managed to save much of the content, by retreating to pure intergovernmental form, but opened itself to the charge of undemocratically cancelling out the no votes in two countries. If ever the project of a Convention is revived, one dedicated to forming a closer union, a new form of submission and ratification may be required in a Union of now 27 states. The idea of an all-European referendum, raised at the Convention would be a majoritarian mode that in case of a positive result could only produce antagonism in many countries.Footnote 68 Much more productive would be the election of amending conventions in all the states, that would then delegate members to a new, final drafting and amending convention of the whole operating by rules somewhere between majority and unanimity, e.g. ‘double majority’. It is of course possible, that even such a new scenario would not be able to bypass the normal ratification process of each state, including referenda. But the level of legitimacy generated by the expanded procedure would both promote passage in the states, and allow more convincing, collective response to states refusing to ratify.

To sum up: the post-sovereign democratic multi-stage model represents a fundamental innovation in the history of constitutional law and politics. While the model is strictly applicable only in the case of transitions from dictatorships, its principles can help increase the legitimacy of other democratic alternatives. Aside from exceptional circumstances (the U.S in 1787 and India in 1948–1950) it is in the domain of legitimacy creation that the superiority of the new model can be demonstrated.