1. Introduction

Several ancient large-scale collisional convergent margins are preserved worldwide where the upper crust is usually scantly preserved, while in the Himalayan collisional orogen, there are more than 2000 km of upper, middle and locally lower crustal rocks. The Himalayan arc has become the type model for a continent–continent collisional orogen (Cottle et al. Reference Cottle, Larson and Kellett2015). The exhumation of high-grade metamorphic domes is a broadly dispersed tectonic manifestation within the Himalaya and southern Tibet that formed in response to the collision of India and Eurasia in early Cenozoic time (e.g. Gansser, Reference Gansser1964; Molnar & Tapponnier, Reference Molnar and Tapponnier1975; Tapponnier & Molnar, Reference Tapponnier and Molnar1977; Allégre et al. Reference Allégre, Courtillot, Tapponnier, Hirn, Mattauer, Coulon, Jaeger, Achache, Schärer, Marcoux, Burg, Girardeau, Armijo, Gariépy, Göpel, Tindong, Xuchang, Chenfa, Guangqin, Baoyu, Jiwen, Naiwen, Guoming, Tonglin, Xibin, Wanming, Huaibin, Yougong, Ji, Hongrong, Peisheng, Songchan, Bixiang, Yaoxiu and Xu1984; Yin & Harrison, Reference Yin and Harrison2000; Yin, Reference Yin2006). Two types of gneiss domes occur in the Himalaya. One type appears in the southern portion of the Tibetan Plateau, and they are generally referred to as North Himalayan gneiss domes (Hodges, Reference Hodges2000); examples include the Leo Pargil dome (LPD), Ama Drime Massif and Gurla Mandhata dome (GMD). Another type of gneiss dome formed further north along the arc of the Himalaya; examples include the Malashan, Ramba, Kangmar and Yardoi domes (e.g. Guo et al. Reference Guo, Zhang and Zhang2008; Jessup et al. Reference Jessup, Newell, Cottle, Berger and Spotila2008). Exhumation of North Himalayan gneissic domes in the Himalaya is commonly assumed to involve S-directed mid-crustal flow (e.g. Lee et al. Reference Lee, Hacker, Dinklage, Wang, Gans, Calvert, Wan, Chen, Blythe and McClelland2000, Reference Lee, Hacker and Wang2004; Beaumont et al. Reference Beaumont, Jamieson, Nguyen and Lee2001, Reference Beaumont, Jamieson, Nguyen and Medvedev2004) and orogen-parallel extension (e.g. Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Yin, Kapp, Harrison, Manning, Ryerson, Lin and Jinghui2002; Thiede et al. Reference Thiede, Arrowsmith, Bookhagen, McWilliams, Sobel and Strecker2006; Jessup et al. Reference Jessup, Newell, Cottle, Berger and Spotila2008); as well tectonic wedging models (Webb et al. Reference Webb, Yin, Harrison, Célérier and Burgess2007, Reference Webb, Guo, Clift, Husson, Müller, Costantino, Yin, Xu, Cao and Wang2017; Yin, Reference Yin2006), or duplexing models posit that the crystalline core of the Himalayan orogen was built via thrust horse accretion (He et al. Reference He, Webb, Larson, Martin and Schmitt2015; Larson et al. Reference Larson, Ambrose, Webb, Cottle and Shrestha2015).

The higher Himalayan gneissic domes are exposed in different tectonic settings, and these domes have different thermal, kinematic and rheological characteristics in relation to their bounding shear zones. The higher Himalayan gneissic domes encompass various processes related to the evolution of the upper and middle crust, including the rate and timing of metamorphism. U–Pb dating of zircons from migmatite helps to connect partial melting and melt crystallization with orogenic processes in the Himalaya, while Hf isotope data provide evidence of the tectonic provenance (juvenile versus evolved reworked crust) (Griffin et al. Reference Griffin, Wang, Jackson, Pearson, O’Reilly, Xu and Zhou2002, Reference Griffin, Belousova, Shee, Pearson and O’Reilly2004). Trace-element abundances and ratios are helpful in distinguishing zircons from different sources (e.g. Chyi, Reference Chyi and Craig1986; Heaman et al. Reference Heaman, Bowins and Crocket1990). The combination of U–Pb, trace-element and Hf isotopic systems provides us with a better understanding of the tectonometamorphic units involved (Griffin et al. Reference Griffin, Belousova, Shee, Pearson and O’Reilly2004).

Several previous studies have suggested that the sediments of the Lesser Himalayan Sequence (LHS) and Greater Himalayan Sequence (GHS) were deposited on the proximal and distal parts of the proto-northern Indian passive continental margin, respectively (Brookfield, Reference Brookfield1993; Myrow et al. Reference Myrow, Hughes, Paulsen, Williams, Parcha, Thompson, Bowring, Peng and Ahluwalia2003, Reference Myrow, Hughes, Goodge, Fanning, Williams, Peng, Bhargava, Parcha and Pogue2010). The channel flow model (Jamieson et al. Reference Jamieson, Beaumont, Nguyen and Grujic2006) proposed a single passive margin with the source of the GHS being from a distal Indian source. However, the channel flow model hypothesis is paradoxically based on stratigraphic, isotopic and geochemical evidence (Ahmad et al. Reference Ahmad, Harris, Bickle, Chapman, Bunbury and Prince2000; DeCelles et al. Reference DeCelles, Gehrels, Quade, LaReau and Spurlin2000; Robinson et al. Reference Robinson, DeCelles, Patchett and Garzione2001; Yoshida & Upreti, Reference Yoshida and Upreti2006; Murphy, Reference Murphy2007; Imayama & Arita, Reference Imayama and Arita2008; Spencer et al. Reference Spencer, Harris, Sachan and Saxena2011). The Lesser Himalayan sediments were derived from the Aravalli craton (Spencer et al. Reference Spencer, Harris, Sachan and Saxena2011, Reference Spencer, Dyck, Mottram, Roberts, Yao and Martin2019). The LHS consists of a thick pile of Palaeoproterozoic sediments representing a continental arc–back-arc system and not a passive margin (Kohn et al. Reference Kohn, Paul and Corrie2010). Kohn et al. (Reference Kohn, Paul and Corrie2010) stated that these rocks are volcanogenic sediment intermixed with the volcanic intrusive. The Palaeoproterozoic granite intruded the LHS over the entire length of the Himalaya. These granitic zircons were transported from the distal part to the GHS (Kohn et al. Reference Kohn, Paul and Corrie2010).

The GHS was distally separated from the Indian continent at the initial stage, and later on, this sequence thrust over the Main Central Thrust during Cenozoic time. The ϵNd values for the GHS and Tethyan Himalayan Sequence (THS) are more juvenile than the LHS (average value of −22), whereas the average ϵNd value of the GHS (−13) shows that the GHS group of rocks is more juvenile than that of the Indian craton, which reveals that the GHS is not the part of the Indian shield (Spencer et al. Reference Spencer, Harris, Sachan and Saxena2011). It is similar to the other Palaeoproterozoic terranes like the Arabian–Nubian Shield, Antarctica. Previous studies (such as DeCelles et al. Reference DeCelles, Gehrels, Quade, LaReau and Spurlin2000; Upreti & Yoshida, Reference Upreti and Yoshida2005; Yoshida & Upreti, Reference Yoshida and Upreti2006) suggested that these Palaeoproterozoic terranes have similar peaks as the GHS.

In this study, we present new geochronological data along with trace elements and the first Hf isotope data for migmatitic zircons from the LPD to constrain the timing of partial melting, palaeogeographic reconstruction and the provenance of the LPD rocks (do they represent the THS or GHS?). The source of inherited zircons may be locally or distally derived. Our geochronological dataset will test the local versus distal derivation of the detrital zircons.

2. Geological background

The LPD in NW India is a 30 km wide, NE-striking, elongate dome structure comprising amphibolite-facies metamorphic rocks and cored by migmatite and leucogranite. The metamorphic rocks in the dome are intruded by multiple leucogranite dykes and sills. Structurally, the LPD is more analogous to other domes formed by orogen-parallel extension, such as the Gurla Mandhata dome and Ama Drime Massif (Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Yin, Kapp, Harrison, Manning, Ryerson, Lin and Jinghui2002; Thiede et al. Reference Thiede, Arrowsmith, Bookhagen, McWilliams, Sobel and Strecker2006; Jessup et al. Reference Jessup, Newell, Cottle, Berger and Spotila2008) in comparison to gneiss domes present regionally in the GHS, such as the Gianbul and Umasi domes to the northwest. The LPD is limited to the north by the Karakoram Fault, east by the Zada Basin of the upper Sutlej river, and south by the Southern Tibet Detachment System (STDS). The west side of the dome exposes the W-directed, W-dipping ductile Leo Pargil Shear Zone (LPSZ: e.g. Thiede et al. Reference Thiede, Arrowsmith, Bookhagen, McWilliams, Sobel and Strecker2006; Langille et al. Reference Langille, Jessup, Cottle, Lederer and Ahmad2012, Reference Langille, Jessup, Cottle and Ahmad2014) on the border between northwestern India and western Tibet. The LPSZ on the SW flank of the dome is W-directed and, along with brittle normal faults, accommodates exhumation of the high-grade core (Thiede et al. Reference Thiede, Arrowsmith, Bookhagen, McWilliams, Sobel and Strecker2006).

The Leo Pargil, Gurla Mandhata and Yardoi domes are distinguished from other North Himalayan gneiss domes because of their age (Yardoi) and the orientation of their normal bounding faults (LPD, GMD), which are broadly N–S- versus E–W-trending normal faults/rift basins for Kangmar, etc.

Orogen-perpendicular normal faults play a substantial role in the exhumation of the LPD. Ni & Barazangi (Reference Ni and Barazangi1985) stated that the LPD was exhumed within a pull-apart structure related to the Karakorum fault owing to the development of extensional forces. Leech (Reference Leech2008) advocated that the Karakorum fault acted as a barrier for mid-crustal channel flow, and the gneiss dome is exposed in the east of the Karakorum fault termination. Thiede et al. (Reference Thiede, Arrowsmith, Bookhagen, McWilliams, Sobel and Strecker2006) outlined the thermochronological constraints on the development of the LPD. Jessup & Cottle (Reference Jessup and Cottle2010) constrained partial melting and strain localization in the LPD. Langille et al. (Reference Langille, Jessup, Cottle, Lederer and Ahmad2012) described the pressure–temperature constraints with monazite geochronology of leucogranite of the LPD. Lederer et al. (Reference Lederer, Cottle, Jessup, Langille and Ahmad2013) documented a meagre contribution of pre-Himalayan components in the investigated area based on monazite geochronology of leucogranite.

In the Spiti Valley, the dome is demarcated as the rocks that report basically top-down-to-the-W shearing related to the LPSZ. The Haimanta Group of pelitic rocks (THS) adjoining the boundaries of the dome that are intervened by the several networks of the leucogranite injection complex lack evidence for in situ partial melting. The THS is characterized as a separate tectonic component of the crystalline core of the Himalaya. Chambers et al. (Reference Chambers, Caddick, Argles, Horstwood, Sherlock, Harris, Parrish and Ahmad2009) identified that it shares a highly comparable tectonic evolution to that of the uppermost GHS in central Nepal (Vannay & Hodges, Reference Vannay and Hodges1996; Coleman & Hodges, Reference Coleman and Hodges1998; Godin et al. Reference Godin, Parrish, Brown and Hodges2001; Gleeson & Godin, Reference Gleeson and Godin2006). The Haimanta Group may characterize a comparatively passive ‘lid’ to a ‘GHS channel’ confining strong, ductile deformation beneath. In the central part of the dome, these rocks are transformed into migmatite, and leucosome is generated through the partial melting process of pelitic rocks. Langille et al. (Reference Langille, Jessup, Cottle, Lederer and Ahmad2012) assumed that these rocks are related to the GHS, not to the THS, based upon structural position. Therefore, there is also disagreement over whether these rocks belong to the THS or GHS, as debated by various workers (Chambers et al. Reference Chambers, Caddick, Argles, Horstwood, Sherlock, Harris, Parrish and Ahmad2009; Langille et al. Reference Langille, Jessup, Cottle, Lederer and Ahmad2012).

3. Local geology

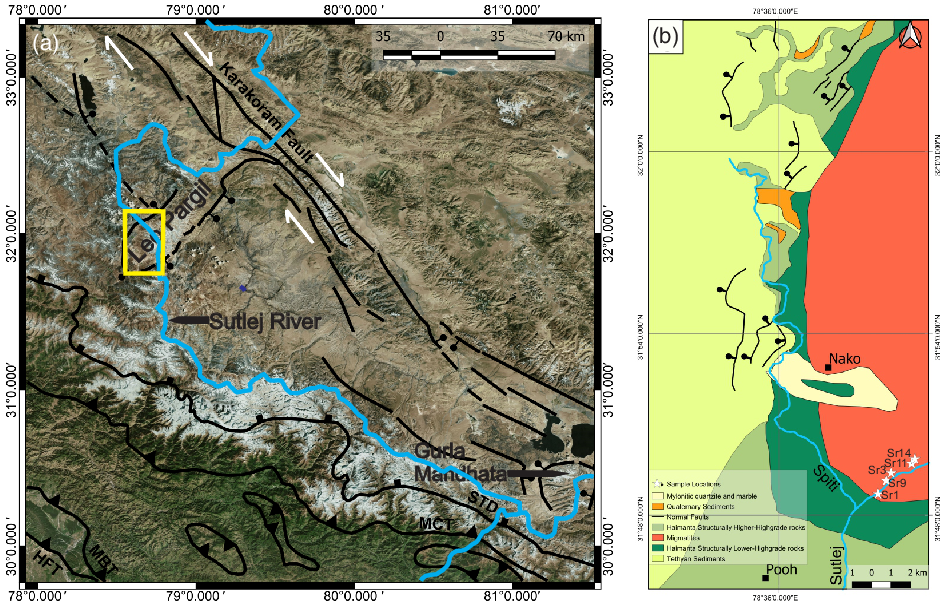

The present study was carried out in the upper Sutlej river valley (Leo Pargil region in Himachal Pradesh; Fig. 1a–c). In the study area, the footwall of the Southern Tibetan Detachment (STD) comprises the High Himalayan Crystalline sequence or GHS rocks (Mehta, Reference Mehta1977; Frank et al. Reference Frank, Gansser and Trommsdorff1977; Thöni, Reference Thöni1977; Steck et al. Reference Steck, Spring, Vannay, Masson, Stutz, Bucher, Marchant, Tieche, Steck, Spring, Vannay, Masson, Stutz, Bucher and Marchant1993; Montomoli et al. Reference Montomoli, Carosi and Iaccarino2015). The high-grade amphibolite-facies rocks in the southern end of the dome are detached from low- to moderate-grade metasedimentary rocks to the west by the LPSZ (Thiede et al. Reference Thiede, Arrowsmith, Bookhagen, McWilliams, Sobel and Strecker2006). Here, the shear zone is a W- to a SW-dipping zone that accommodates normal-displacement during dominantly top-down-to-the-W shearing (Langille et al. Reference Langille, Jessup, Cottle, Lederer and Ahmad2012). The northern limit of the LPD is within the Karakoram Fault system, but it does not extend further to the east to meet the Ayi Shan.

Fig. 1. (a) Structural map of the NW Indian Himalaya, modified after Thiede et al. (Reference Thiede, Arrowsmith, Bookhagen, McWilliams, Sobel and Strecker2006 and references therein). MCT – Main Central Thrust; MBT – Main Boundary Thrust; HFT – Himalayan Frontal Thrust; STD – South Tibetan Detachment system. (b) Sample location and geological map of the studied area (modified after Thiede et al. Reference Thiede, Arrowsmith, Bookhagen, McWilliams, Sobel and Strecker2006).

The amphibolite-facies rocks are garnet–biotite–staurolite–kyanite schist. On the SW flank of the dome, the LPSZ is a dispersed area of W-dipping, amphibolite-facies schist, quartzite, leucogranite and marble, interleaved with and intruded by younger leucogranite that was deformed during top-down-to-the-W shearing (Thiede et al. Reference Thiede, Arrowsmith, Bookhagen, McWilliams, Sobel and Strecker2006; Leech, Reference Leech2008; Langille et al. Reference Langille, Jessup, Cottle, Lederer and Ahmad2012; Lederer et al. Reference Lederer, Cottle, Jessup, Langille and Ahmad2013). Schist ranges from biotite to garnet grade adjacent to Sumdo and Chango, up to sillimanite grade within the LPD. Migmatites are exposed in the eastern part of the dome. The presence of mesoscopic shear bands in the migmatitic gneiss indicates a transition to a top-down-to-the-E shear sense on the dome’s southeastern part (Langille et al. Reference Langille, Jessup, Cottle, Lederer and Ahmad2012).

4. Petrographic details

The migmatite from the upper Sutlej valley mainly consists of schlieren migmatite (including stromatite) with boudinaged leucosomes displaying a ‘pinch-and-swell’ structure differentiated from the dark-coloured selvages (melanosome) (Fig. 2b). The leucosomes are commonly restricted to inter-boudin partitions (Fig. 2b, c) and fold hinges and are often parallel to the mesosome foliation (Fig. 2a, d, e, f). These migmatites have a consistent compositional ratio of melanosome and leucosome (Fig. 2e, f). Leucosome–melanosome banding with visible fold and shear structures is preserved in the host schlieren migmatite (Fig. 2e).

Fig. 2. Field photographs showing the occurrences of migmatite in the upper Sutlej valley (Leo Pargil). (a) Migmatite with a relatively constant ratio of melanosome to leucosome. Length of hammer for scale is 30 cm. (b) Migmatitic metapelite with boudinaged leucosome. Length of notebook for scale is 22 cm. (c) Gneissic rock with boudinaged leucosome. Length of pen for scale is 14 cm. (d) Migmatite with nearly concordant leucosomes and melanosomes. Length of pen for scale is 14 cm. (e) Migmatite with constant ratio of melanosome to leucosome; sharp contact of leucogranite body with migmatite. Length of object for scale 8 cm. (f) Migmatite with leucosome and melanosome layer; leucosome and melanosome are nearly parallel to each other. Length of hammer for scale is 30 cm.

Five samples were collected from migmatite at locations that range from near the confluence of the Sutlej and Spiti rivers (Khab) to the northeast along the Sutlej river (Fig. 1b). We analysed whole migmatite samples rather than separating out the thinly layered leucosome from the melanosome except in sample WIHG-SR3. Two types of migmatite samples were observed in the LPD: (a) aluminosilicate-bearing migmatite and (b) biotite–amphibole-bearing migmatite. The studied migmatites are generally composed of plagioclase (15–20 %), K-feldspar (20–25 %), quartz (40–45 %), amphibole (∼10 %) and biotite (10–15 %), with minor amounts of muscovite, garnet, apatite, zircon and Fe–Ti oxides.

5. Analytical methods

Zircon concentrates were isolated from c. 3 kg of rock samples by standard density and magnetic separation techniques and subsequently mounted in epoxy for cathodoluminescence (CL) imaging. The images were used to select analysis locations in uniform crystal domains, avoiding cracks and alteration.

Zircon grains were analysed by laser ablation split-stream inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LASS-ICP-MS) at the John de Laeter Centre of Curtin University, Perth (Australia). Zircon grains were ablated with a Resonetics resolution M-50A-LR, incorporating a COMPex 102 excimer laser. Following two cleaning pulses and a 40 s period of background analysis, samples were spot ablated for 30 s at 10 Hz using a 50 μm beam and laser energy of 2.2 J cm−2 at the sample surface. The sample cell was flushed by ultrahigh purity He (0.68 L min−1) and N2 (2.8 mL min−1). Isotopic intensities were measured using an Agilent 7700 s quadrupole ICP-MS for the age and trace-element determination and a Nu Instruments Plasma II multi-collector (MC)-ICP-MS for the Hf isotope determination using high purity Ar as the plasma gas (flow rate 0.98 L min−1). All isotopes on the MC-ICP-MS (180Hf, 179Hf, 178Hf, 177Hf, 176Hf, 175Lu, 174Hf, 173Yb, 172Yb and 171Yb) were counted on the Faraday collector array for Hf isotope analysis. Time-resolved data were baseline subtracted and reduced using Iolite (Paton et al. Reference Paton, Woodhead, Hellstrom, Hergt, Greig and Maas2010) after Woodhead et al. (Reference Woodhead, Hergt, Shelley, Eggins and Kemp2004) and Spencer et al. (Reference Spencer, Yakymchuk and Ghaznavi2017), where 176Yb and 176Lu were removed from the 176 mass signals using 176Yb/173Yb = 0.7962 (Chu et al. Reference Chu, Taylor, Chavagnac, Nesbitt, Boella, Milton, German, Bayon and Burton2002) and 176Lu/175Lu = 0.02655 (Chu et al. Reference Chu, Taylor, Chavagnac, Nesbitt, Boella, Milton, German, Bayon and Burton2002) with an exponential mass bias correction assuming 172Yb/173Yb = 1.35274 (Chu et al. Reference Chu, Taylor, Chavagnac, Nesbitt, Boella, Milton, German, Bayon and Burton2002). For mass bias correction, the ‘interference’ ‘corrected’ 176Hf/177Hf ratio was normalized to 179Hf/177Hf = 0.7325 (Patchett & Tatsumoto, Reference Patchett and Tatsumoto1980).

Standard-sample bracketing using Mud Tank zircon as the primary reference material was used to monitor instrumental drift and accuracy of internal Hf isotope corrections for all Lu–Hf analyses measured at the GeoHistory Facility. The Mud Tank standard analysed during this study has an average corrected 176Hf/177Hf value of 0.282507 ± 0.000003 (2σ) (MSWD = 0.05). The accepted 176Hf/177Hf value and its uncertainty for the Mud Tank standard zircon is 0.282505 ± 0.000044 (Woodhead & Hergt, Reference Woodhead and Hergt2005). The zircon 91500 standard analysed throughout the session gave an average 176Hf/177Hf value of 0.282296 ± 0.000005 (2σ), within the uncertainty of the accepted value of 0.282306 ± 0.000005 (2σ) (Woodhead & Hergt, Reference Woodhead and Hergt2005). The zircon GJ-1 standard analysed throughout the session gave an average 176Hf/177Hf value of 0.282034 ± 0.00004 (2σ), within the uncertainty of the accepted value of 0.282000 ± 0.000005 (2σ) (Morel et al. Reference Morel, Nebel, Nebel-Jacobsen, Miller and Vroon2008). To monitor the accuracy of mass bias correction, the corrected 178Hf/177Hf ratio was calculated and yielded an average of 1.46707 ± 0.0001, and the 180Hf/177Hf ratio was calculated and yielded an average of 1.88682 ± 0.0002, which is within uncertainty of the value reported by Spencer et al. (Reference Spencer, Dyck, Mottram, Roberts, Yao and Martin2019) (online Supplementary Material Figs S1, S2).

Ages were normalized using standard-sample bracketing with 91500 zircon as the primary reference material. The self-normalized corrected 206Pb–238U weighted mean age for 91500 is 1062.1 ± 4.1 Ma (MSWD = 0.43). Secondary standards were also run to validate the correction. GJ-1 yielded a weighted mean 206Pb–238U age of 598.7 ± 1.5 Ma (MSWD = 2.9) (Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Pearson, Griffin and Belousova2004). OGC yielded a weighted mean 207Pb–206Pb age of 3466.3 ± 3.5 Ma (MSWD = 2.6) (Stern et al. Reference Stern, Bodorkos, Kamo, Hickman and Corfu2009). Plesovice yielded a weighted mean 206Pb–238U age of 337.6 ± 1.2 Ma (MSWD = 1.9) (Sláma et al. Reference Sláma, Košler, Condon, Crowley, Gerdes, Hanchar, Horstwood, Morris, Nasdala, Norberg, Schaltegger, Schoene, Tubrett and Whitehouse2008). R33 yielded a weighted mean 206Pb–238U age of 417.8 ± 1.7 Ma (MSWD = 2.0). All of the secondary standards are within the uncertainty of the published values. Weighted means were calculated using KDX (Spencer et al. Reference Spencer, Yakymchuk and Ghaznavi2017) (online Supplementary Material Figs S3, S4).

Concordant zircon ages were defined as those for which the calculated ages from two U–Pb systems lie within the uncertainty of one another (Spencer et al. Reference Spencer, Kirkland and Taylor2016). Propagated uncertainties larger than 10 % were considered unreasonable, and these data were excluded. εHf(t) values were calculated for all data using the 176Lu decay constant = 1.865 × 10−11 year−1 set out by Scherer et al. (Reference Scherer, Münker and Mezger2001). Chondritic values are after Bouvier et al. (Reference Bouvier, Vervoort and Patchett2008); 176Hf/177Hf chondritic uniform reservoir (CHUR) = 0.282785 and 176Lu/177Hf CHUR = 0.0336. Depleted mantle model ages were calculated using these values. Depleted mantle values are 176Hf/177Hf = 0.28325 and 176Lu/177Hf = 0.0384 after Griffin et al. (Reference Griffin, Wang, Jackson, Pearson, O’Reilly, Xu and Zhou2002). For zircon grains with ages <1500 Ma, the 206Pb–238U age was used (Spencer et al. Reference Spencer, Kirkland and Taylor2016).

For trace-element analyses, 90Zr (assuming ∼45 wt % Zr) was used as an internal standard, and peaks were measured at 49Ti, 90Zr, 139La, 140Ce, 141Pr, 146Nd, 147Sm, 153Eu, 157Gd, 163Dy, 172Yb, 175Lu, 206Pb, 232Th and 238U. Reference material 91500 was used as the primary standard. Measured trace-element concentrations are within ∼10 % of reference values.

6. Results

6.a. Zircon morphology and U–Pb ages

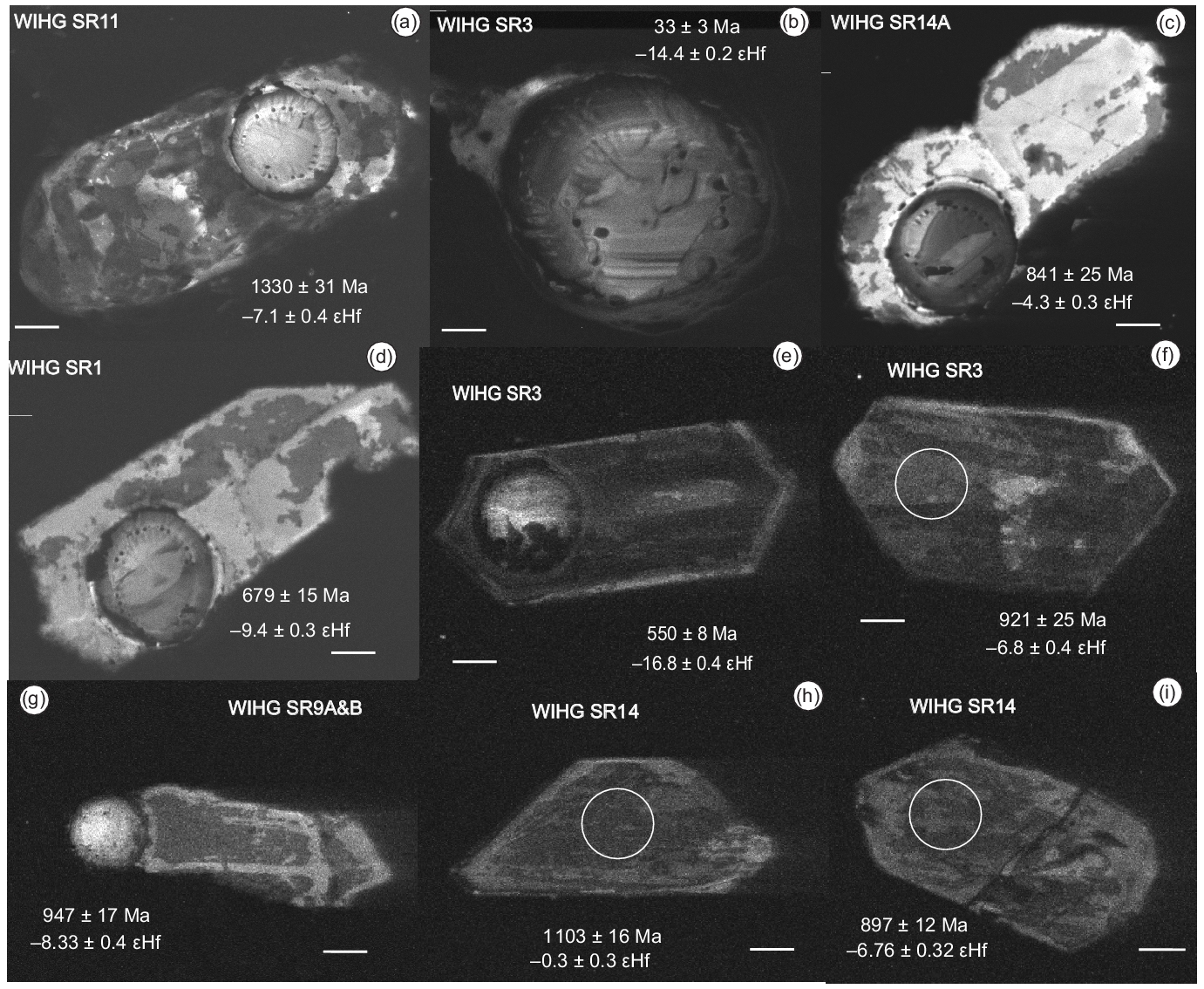

Zircons from five migmatite samples were analysed. The zircon grains in each sample were euhedral to subhedral, irregular (a few have oval shapes) and ∼100–190 μm long. A few grains are elongated and prismatic (Fig. 3) sub-rounded to rounded. Zircon grains exhibit core–rim structures with regular patchy or weakly oscillatory zones. The homogeneous/unzoned rims of weakly luminescent zircon grains (Fig. 3) display resorbed inherited luminescent cores. A few zircons show younger overgrowths surrounding the complex structure with Proterozoic inherited cores in sample WIHG-SR3.

Fig. 3. Cathodoluminescence images of analysed zircon grains of representative samples of migmatite from the upper Sutlej valley (Leo Pargil region), India. (a) WIHG-SR1; (b) WIHG-SR3; (c) WIHG-SR9; (d) WIHG-SR11; and (e) WIHG-SR14A with analysed spots, their ages and ϵHf value.

The rare earth element content of the analysed zircons shows positive Ce anomalies and negative Eu anomalies (Fig. 4). The majority of the zircons show enriched heavy rare earth elements (HREE), while a few zircons show flat light rare earth element (LREE) patterns (Fig. 4) (online Supplementary Material Table S1). The U–Pb age data for the migmatite range from 1360 to 24 Ma (online Supplementary Material Table S2). Samples WIHG-SR9A, WIHG-SR14A, WIHG-SR11 and WIHG-SR1A show an age range of 1360 to 350 Ma. Two major age peaks are observed at 820 Ma (n = 7) and 950 Ma (n = 7), and three minor age peaks at around 670 Ma (n = 4), 900 Ma (n = 4) and 1050 Ma (n = 5) (Fig. 6). Concordia plots are presented at the 2σ level. All analyses are shown on individual concordia diagrams (Fig. 5a–e); however, discordant analyses (n = 18) were not included in the relative probability density diagram (Fig. 6). Discordant ages track along a discordia line. Sample WIHG-SR3 shows age variation from 1310 to 24 Ma with an implied lower intercept of 15.6 ± 2.2 Ma ‘not anchored’ on the concordia line. These discordant ages are plotted on a 207Pb/206Pb versus 238U/206Pb concordia diagram (Tera & Wasserburg, Reference Tera and Wasserburg1972) in Figure 7.

Fig. 4. Chondrite-normalized averaged trace-element abundances of zircon from different migmatites. Chondrite values are from Taylor & McLennan (Reference Taylor and McLennan1985).

Fig. 5. Concordia diagrams of U–Pb dating for detrital zircons samples (a) WIHG-SR1; (b) WIHG-SR14A; (c) WIHG-SR9A and WIHG-SR9B; (d) WIHG-SR3; (e) WIHG-SR11 of studied migmatite from the Leo Pargil dome, India. Inset: Concordia diagram showing only concordance data. Concordia diagram plotted using IsoplotR (Vermeesch, Reference Vermeesch2018).

Fig. 6. Relative age probability and histogram plot of detrital zircons plotted using IsoplotR (Vermeesch, Reference Vermeesch2018). Density diagram of detrital zircons of representative zircon samples WIHG-SR1, WIHG-SR14A, WIHG-SR9A, WIHG-SR9B, WIHG-SR11 and WIHG-SR3. Published data from the pGHS Sutlej Himalaya (Richards et al. Reference Richards, Argles, Harris, Parrish, Ahmad, Darbyshire and Draganits2005), THS Sutlej (Webb et al. Reference Webb, Yin, Harrison, Célérier, Gehrels, Manning and Grove2011) and THS Garhwal (Myrow et al. Reference Myrow, Hughes, Goodge, Fanning, Williams, Peng, Bhargava, Parcha and Pogue2010) are plotted.

Fig. 7. Tera-Wasserburg concordia plot for the investigated zircons (WIHG-SR3) from the Leo Pargil migmatite.

6.b. U–Pb geochronology and zircon Hf isotopes

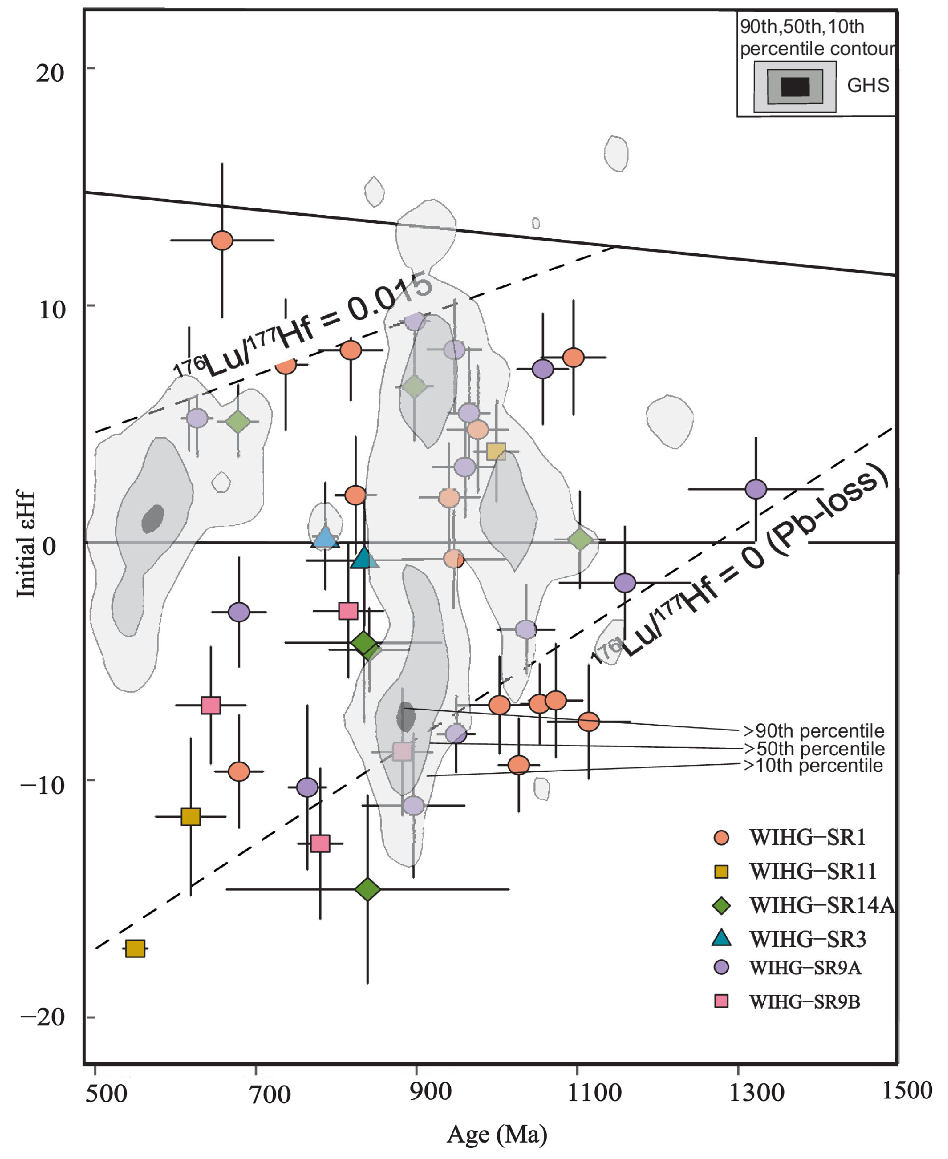

A total of 29 Hf isotope analysis ages range from 1360 to 536 Ma from sample WIHG-SR1. The analyses yield consistent 176Hf/177Hf ratios of between 0.281599 and 0.282744, corresponding to ϵHf values of −9.4 to 13.0. The TDM2 ages are 0.76 to 2.42 Ga with a weighted mean age of 0.96 Ga, and zircon Th/U ratios range from 0.2 to 0.86. A total of 11 analyses were collected on zircons from sample WIHG-SR11. Ages vary from 1330 to 490 Ma, and zircon Th/U ratios range from 0.0075 to 0.9. The 176Hf/177Hf ratios range from 0.281756 to 0.282545. The calculated ϵHf values are −16.8 to 6.8, and the equivalent TDM2 ages are 1.3–2.6 Ga (mean of 2.04 Ga). A total of 14 analyses were obtained from sample WIHG-SR14A. Ages range from 1103 to 583 Ma, and corresponding 176Hf/177Hf ratios range from 0.281657 to 0.282528. The calculated ϵHf values are −14.4 to 6.8, and the analogous TDM2 ages are 1.3–2.6 Ga (mean of 1.9 Ga). Zircon Th/U ratios of WIHG-SR14A range from 0.087 to 0.89. Twenty-three analyses were obtained from sample WIHG-SR3, and ages range from 1310 to 24 Ma. Th/U ratios of WIHG-SR3 range from 0.008 to 0.49. Most of the analyses are discordant. The 176Hf/177Hf ratios vary from 0.281792 to 0.282516. The calculated ϵHf values are −17.5 to 2.3, and the comparable TDM2 ages are 1.34–2.4 Ga (mean of 2.0 Ga). A total of 19 analyses were collected on zircons from sample WIHG-SR9A, and ages range from 1322 to 617 Ma. The 176Hf/177Hf ratios range from 0.281406 to 0.282705. The calculated ϵHf values are −10.9 to 9.6, and the corresponding TDM2 ages are 1.1–2.4 Ga (weighted mean of 1.7 Ga). Zircon Th/U ratios range from 0.144 to 1.258. All the data are listed in online Supplementary Material Tables S2 and S3. Initial ϵHf versus age is plotted in Figure 8.

Fig. 8. 2dKDE of the GHS (Spencer et al. Reference Spencer, Dyck, Mottram, Roberts, Yao and Martin2019), compared with this study. Plot of ϵHf and U–Pb crystallization ages for zircon and probable source regions. DM – depleted mantle; CHUR – chondritic uniform reservoir. Note the widespread values for most samples indicating potential crustal mixing. ϵHf data were calculated using the decay constant of 1.867 10−11 year−1 (Söderlund et al. Reference Söderlund, Patchett, Vervoort and Isachsen2004) and the CHUR parameters of Bouvier et al. (Reference Bouvier, Vervoort and Patchett2008). DM evolution curve was defined by (176Hf/177Hf) DM = 0.28325 and (176Lu/177Hf) DM = 0.0388. Error bars represent errors reported in online Supplementary Material Table S3.

7. Discussion

Partial melting and associated magma migration not only influences the thermal and rheological properties of orogenic crust (Whitney et al. Reference Whitney, Teyssier, Fayon, Hamilton and Heizler2003) but also affects chemical differentiation (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Korhonen and Siddoway2011; Sawyer et al. Reference Sawyer, Cesare and Brown2011) and allows ductile deformation of continental crust (Hopkinson et al. Reference Hopkinson, Harris, Roberts, Warren, Hammond, Spencer and Parrish2019). Zircon in migmatite provides a robust geochronological proxy for partial melting and provides insight into the tectonic environment of its host rocks (Calderón et al. Reference Calderón, Hervé, Massonne, Tassinari, Pankhurst, Godoy and Theye2007; Wu et al. Reference Wu, Zheng, Zhang, Zhao, Wu and Liu2007; Gordon et al. Reference Gordon, Whitney, Teyssier and Fossen2013; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Wu, Wang, Gao, Qin, Liu, Yang and Gong2014; Maki et al. Reference Maki, Yui, Miyazaki, Fukuyama, Wang, Martens, Grove and Liou2014; Moghadam et al. Reference Moghadam, Li, Stern, Ghorbani and Bakhshizad2016; Li et al. Reference Li, Lin, Li, He and Ge2018). The CL-dark rims and spongy growth and resolved rims of the grains can be related to partial dissolution in a leucosomal melt (WIHG-SR3). Our study helps us to further understand the evolution of gneissic domes in the realm of a collisional orogeny.

Here we first draw information about the nature and provenance of the migmatitic rocks and subsequently address the consequences of the results to understand the styles of partial melting and age to form migmatite. Lastly, we discuss the palaeogeographic reconstruction of our findings.

7.a. Implications for interpreting LPD trace-element and Hf systematics

The high Th/U ratios (0.2–1.5), positive Ce and negative Eu anomalies, as well as enrichment in HREEs in most of the studied zircons, are consistent with a magmatic origin (Belousova et al. Reference Belousova, Griffin, O’Reilly and Fisher2002; Rubatto, Reference Rubatto2002; Corfu et al. Reference Corfu, Hanchar, Hoskin and Kinny2003; Wu & Zheng, Reference Wu and Zheng2004; Warren et al. Reference Warren, Greenwood, Argles, Roberts, Parrish and Harris2019; Yakymchuk & Brown, Reference Yakymchuk and Brown2019). The majority of the zircons are HREE enriched, but two to three grains with flatter LREE patterns in each sample (except WIHG-SR9B; Fig. 4) most likely reflect a change in the source material or subsequent metamorphism (Whitehouse & Platt, Reference Whitehouse and Platt2003). Zircons derived from the leucosomal part of sample WIHG-SR3 have a very low to moderate Th/U ratio (0.007–0.46), suggesting a recrystallized or metamorphic origin (Liati et al. Reference Liati, Gebauer and Wysoczanski2002). These zircons have consistent HREE-enriched patterns but variable LREE and positive Ce and negative Eu anomalies (Fig. 4), suggesting the zircon grew from a melt (Rubatto et al. Reference Rubatto, Hermann, Berger and Engi2009). The weak oscillatory zoning, low to moderate Th/U ratio and enriched HREE pattern in the zircons demonstrates the zircons’ pristine nature. This is more likely restructured by dissolution–reprecipitation (Hoskin & Black, Reference Hoskin and Black2000; Wu & Zheng, Reference Wu and Zheng2004). The older inherited zircons are detrital and were reprocessed during past magmatic events. Given that the leucocratic melt is oversaturated in zircon and the protracted wall-rock assimilation, pristine homogeneous zircons are rare and most contain inherited cores.

Zircon with Th/U <0.01 is likely metamorphic, but those with higher Th/U ratios (0.01–0.1) can be either igneous or metamorphic in origin (Rubatto, Reference Rubatto2002, Reference Rubatto2017; Hoskin & Schaltegger, Reference Hoskin and Schaltegger2003; Rubatto & Hermann, Reference Rubatto and Hermann2007; Tu et al. Reference Tu, Ji, Gong, Yan and Han2016; Yakymchuk et al. 2018). The Th/U ratio in supra-solidus metamorphic zircon is controlled by the concentration of Th and U in the system (Yakymchuk et al. 2018). The Th/U ratio of zircon in the anatectic melt will hinge on the timing of growth of monazite and zircon in an open system (Rubatto, Reference Rubatto2017; Yakymchuk et al. 2018). In the present study, the melt was rapidly extracted and pooled at higher structural levels, revealing an open system behaviour of the migmatite. In this case, any late crystallized zircon growing in the presence of monazite near the solidus generally should have low Th/U ratios (Stübner et al. Reference Stübner, Grujic, Parrish, Roberts, Kronz, Wooden and Ahmad2014; Kohn, Reference Kohn2017; Yakymchuk et al. 2018; Yakymchuk & Brown, Reference Yakymchuk and Brown2019). Fast melt extraction should enrich the restite in Th and decrease the Th/U ratio in the anatectic melt relative to the source. The Th/U ratio of these young zircons varies from 0.008 to 0.051, while ϵHf varies from −14.6 to −12.7. So, low Th/U zircon with an age of 15 Ma would also likely form close to the solidus.

The signature of the anatectic melt, which is the product of detrital zircon in a metasedimentary source, and the extent of melt homogenization controlled the Hf isotope composition in the zircons (Finch et al. Reference Finch, Weinberg, Barrote and Cawood2021). The restricted variation of ϵHf(t) of between −14.6 and −12.7 in the migmatitic zircon may have resulted from the limited mixing between outside Hf (external melt) and internal Hf (dissolution–reprecipitation) of the inherited zircon. In sample WIHG-SR3, the zircon mantle has a higher Hf176/Hf177 ratio than the inherited core. Zheng et al. (Reference Zheng, Wu, Zhao, Zhang, Xu and Wu2005) and Flowerdew et al. (Reference Flowerdew, Millar, Vaughan, Horstwood and Fanning2006) suggested this is typical for Hf isotope distribution patterns.

7.b. Tectonic implications

Leech (Reference Leech2008) demonstrated seven leucogranites have U–Pb dates ranging from 27 to 19 Ma using sensitive high-resolution ion microprobe (SHRIMP) analysis of samples from the LPD. Thiede et al. (Reference Thiede, Arrowsmith, Bookhagen, McWilliams, Sobel and Strecker2006) reported 40Ar–39Ar white mica ages of 16–14 Ma from the Leo Pargil area and interpreted this age to represent the first phase of rapid cooling. Some zircons from WIHG-SR3 constrain a lower intercept of 15.6 ± 2.2 Ma (Fig. 7), which we interpret as partial melting starting at 30 Ma and melt crystallization occurring at 15 Ma. So, overall, the partial melting event took place in the study area within the span of 15 Ma. The youngest ages of our zircons are consistent with the 40Ar–39Ar ages, and consistent with the melt crystallization at ∼16–15 Ma.

The accretion of granite beneath or within the STD (Scaillet et al. Reference Scaillet, Pichavant and Roux1995; Weinberg & Searle, Reference Weinberg and Searle1999; Searle et al. Reference Searle, Law and Jessup2006; Carosi et al. Reference Carosi, Montomoli, Rubatto and Visonà2013; Lederer et al. Reference Lederer, Cottle, Jessup, Langille and Ahmad2013; Finch et al. Reference Finch, Hasalová, Weinberg and Fanning2014) advocates that the STD acted as a barrier for magma migration, which inhibited magma extraction and accumulation, favouring diffuse melt migration and local accumulation, owing to the lowest transferability of heat from the THS across the STD due to the thermal and rheological barrier represented by the cold rocks of the THS. The thrusting phenomena in the GHS are the most credible heat cradle for the anatexis of the GHS (Molnar et al. Reference Molnar, Chen and Padovani1983; Jaupart & Provost, Reference Jaupart and Provost1985).

The melt generation was intensified in short-duration pulses, and its movement from the lower to higher structural level of the GHS triggered the internal weakening of the Himalayan wedge (Phukon et al. Reference Phukon, Sen, Singh, Sen, Srivastava and Singhal2019 and references therein). Owing to this weakening, gravity collapse in the form of detachment (Southern Tibet Detachment Zone) was produced, which decreased the taper angle of the wedge (Dahlen, Reference Dahlen1984; Robinson et al. Reference Robinson, DeCelles and Copeland2006; Kohn, Reference Kohn2008; Sachan et al. Reference Sachan, Kohn, Saxena and Corrie2010; Finch et al. Reference Finch, Hasalová, Weinberg and Fanning2014). Lastly, the partial melt, which destabilized the Himalayan wedge, was placed synkinematically in the strain shadow zone of the Tethyan rocks within the detachment zone in the form of migmatite and leucogranite (Phukon et al. Reference Phukon, Sen, Singh, Sen, Srivastava and Singhal2019 and references therein). The age of partial melting in the study area is contemporaneous with the movement of the STD (Godin et al. Reference Godin, Grujic, Law and Searle2006).

7.c. Age and provenance of zircon

The Mesoproterozoic inherited zircon was likely derived from orogenic events linking to the assembly of the Rodinia supercontinent (Zeh & Gerdes, Reference Zeh and Gerdes2012; Spencer et al. Reference Spencer, Cawood, Hawkesworth, Prave, Roberts, Horstwood and Whitehouse2015), whereas the Neoproterozoic inherited zircon was likely derived from the Arabian–Nubian Shield and the East African Orogen (Madagascar, Mozambique and Ethiopia). These ages correspond with U–Pb ages reported throughout the Himalayan orogenic belt (e.g. DeCelles et al. Reference DeCelles, Gehrels, Najman, Martin, Carter and Garzanti2004; Cai et al. Reference Cai, Ding and Yue2011; Ravikant et al. Reference Ravikant, Dharwadkar, Golani and Ravindra2011; Spencer et al. Reference Spencer, Harris and Dorais2012, Reference Spencer, Dyck, Mottram, Roberts, Yao and Martin2019; Rubatto et al. Reference Rubatto, Chakraborty and Dasgupta2013).

The Grenville Orogeny and coexisting events (1300–900 Ma) are extensively documented in Laurentia and Gondwana and are associated with the orogenesis process that formed the Rodinia supercontinent (Hoffman, Reference Hoffman1991; Wingate et al. Reference Wingate, Pisarevsky and Evans2002; Meert & Torsvik, Reference Meert and Torsvik2003; Li et al. Reference Li, Li, Li and Liu2008). The group of 960–940 Ma zircons in the GHS is comparable to detrital zircons of similar ages (c. 940 Ma) in the Qiangtang Block of China (Gehrels et al. Reference Gehrels, Kapp, DeCelles, Pullen, Blakey, Weislogel, Ding, Guynn, Martin, McQuarrie and Yin2011). The group of zircons of this age could have ultimately resulted from rocks in parts of East Gondwana or the Tethyan Himalaya, especially Antarctica (Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Zhao, Niu, Dilek and Mo2011). The 1300–1100 Ma zircons from our study are likely derived from the Albany–Fraser belt, and these Grenvillian zircons are also present in the Lhasa terrane (Leier et al. Reference Leier, Kapp, Gehrels and DeCelles2007; Dong et al. Reference Dong, Zhang and Santosh2010).

The ϵHf data from the 1050–950 Ma zircons (−6.9 to +13.6) imply derivation from mixed depleted and enriched crustal sources (Spencer et al. Reference Spencer, Harris and Dorais2012, Reference Spencer, Kirkland and Taylor2016, Reference Spencer, Dyck, Mottram, Roberts, Yao and Martin2019) (Fig. 8). This event is analogous to the Rodinia-age zircon population observed in the Eastern Ghats orogen of India, the Albany–Fraser belt of Australia and Antarctica, and the Rayner Complex of Antarctica (Halpin et al. Reference Halpin, Gerakiteys, Clarke, Belousova and Griffin2005; Veevers & Saeed, Reference Veevers and Saeed2009; Dhuime et al. Reference Dhuime, Hawkesworth, Storey and Cawood2011; Spencer et al. Reference Spencer, Harris and Dorais2012). The 980 Ma zircon may be sourced from the Cathaysia Block that was situated at the northern margin of Indian Gondwana (Yao et al. Reference Yao, Shu, Santosh and Zhao2014), because both the GHS and Cathaysia Block commonly have 980 Ma zircon populations. The Neoproterozoic magmatic arc or belt on the northern periphery of the Rodinia supergroup in the vicinity of the Greater Himalayan basin was a possible source of Neoproterozoic detrital zircon (Mukherjee et al. Reference Mukherjee, Jain, Singhal, Singha, Singh, Kumud and Patel2019).

The weakly developed, tectonically uplifted and eroded granitic belt within the basin might be one of the sources of the ∼1000–850 Ma inherited zircon suite witnessed within the Higher Himalayan Crystalline Sequence and the Lesser Himalayan klippen (Mukherjee et al. Reference Mukherjee, Jain, Singhal, Singha, Singh, Kumud and Patel2019). The lower abundance of ∼850 Ma granitoids in the GHS could be explained by insufficient geochronological data and poor identification of such bodies. Many isolated intrusive granites of ∼900–800 Ma are now identified within different metamorphic nappes such as (a) 823 ± 2 Ma orthogneiss in Black Mountain in the syntaxial area of the NW Himalaya, Pakistan, with several discordant data reported between 1313 and 939 Ma (DiPietro & Isachsen, Reference DiPietro and Isachsen2001), (b) 1220 to 720 Ma zircon ages from the Dhauladhar granite (Dhiman & Singh, Reference Dhiman and Singh2018), (c) 830 Ma zircons from mylonitic augen gneiss in Himachal Pradesh (Webb et al. Reference Webb, Yin, Harrison, Célérier, Gehrels, Manning and Grove2011), (d) 823 ± 5 Ma zircon from the Chor granite of the Jutogh group (Singh et al. Reference Singh, Barley, Brown, Jain and Manickavasagam2002), (e) 860 Ma inherited zircon observed from orthogneiss of Alaknanda valley (Spencer et al. Reference Spencer, Harris and Dorais2012), (f) inherited zircons ranging from 1000 to 900 Ma in the Dhauli Ganga valley migmatite and between 950 and 875 Ma in the leucosome from the same area (Mukherjee et al. Reference Mukherjee, Jain, Singhal, Singha, Singh, Kumud and Patel2019), (g) 839 ± 28 Ma orthogneiss identified above the Main Central Thrust in the Sikkim Himalaya (Mottram et al. Reference Mottram, Argles, Harris, Parrish, Horstwood, Warren and Gupta2014), and (h) 825 ± 9 Ma zircon obtained from augen gneiss in central Bhutan (Richards et al. Reference Richards, Parrish, Harris, Argles and Zhang2006).

The magmatism observed in the Higher Himalayan Crystalline may have occurred due to a superplume under the Rodinia supercontinent causing intracontinental rifting or may be due to Neoproterozoic syn- to post-crustal anatexis. Mottram et al. (Reference Mottram, Argles, Harris, Parrish, Horstwood, Warren and Gupta2014) identified zircon with an age of <800 Ma with ϵNd values ranging from −18.3 to −12.1, representing the GHS. The detrital zircons from the GHS are approximately synchronous with the intrusive granite (c. 800 Ma), proposing that these were deposited in the northern Indian active continental margin. The Neoproterozoic inherited zircons (850–790 Ma) with ϵHf ranging from −14.4 to +9.5 are also found elsewhere in the Himalaya (Spencer et al. Reference Spencer, Harris and Dorais2012, Reference Spencer, Dyck, Mottram, Roberts, Yao and Martin2019). Although the age range is very similar to the Arabian–Nubian Shield, the spread of ϵHf values is much higher (generally between +1 and +13) (Be’eri-Shlevin et al. Reference Be’eri-Shlevin, Katzir, Blichert-Toft, Kleinhanns and Whitehouse2010; Morag et al. Reference Morag, Avigad, Gerdes, Belousova and Harlavan2011, Reference Morag, Avigad, Gerdes and Harlavan2012; Ali et al. Reference Ali, Jeon, Andresen, Li, Harbi and Hegner2014, Reference Ali, Zoheir, Stern, Andresen, Whitehouse and Bishara2016; Robinson et al. Reference Robinson, Foden, Collins and Payne2014). The magmatic relic is identified within the Higher Himalayan Crystalline; the source of this magmatism was probably tectonically eroded during the Bhimphedian Orogeny (Spencer et al. Reference Spencer, Dyck, Mottram, Roberts, Yao and Martin2019).

Another probable source is the Aravalli Range, exactly south of the Himalaya, which has c. 870–800 Ma granitic rocks (Deb et al. Reference Deb, Thorpe, Krstic, Corfu and Davis2001; Van Lente et al. Reference Van Lente, Ashwal, Pandit, Bowring and Torsvik2009; Just et al. Reference Just, Schulz, deWall, Jourdan and Pandit2011). The 800 Ma granitoid could be a probable source for the 790 Ma detrital zircon due to scatter in 206/238 dates. The presently exposed rocks point to early Neoproterozoic magmatic provinces in the Himalaya and Aravalli Range. Therefore, other Greater Himalayan and/or Aravalli c. 930–800 Ma igneous rocks, associated with the presently exposed rocks, could have been exposed at the Earth’s surface at the time of deposition of the (meta)sedimentary rocks and thus could have provided sediment to the GHS. The importance of the c. 800 Ma magmatism is slightly enigmatic but has been uncertainly related to the existence of a superplume underneath the Rodinia continent, causing intracontinental rifting (Li et al. Reference Li, Li, Li and Liu2008). Sharma (Reference Sharma2004) related this to the Malani magmatic event (750 Ma) on the Indian craton; rifting and break-up of the supercontinent resulted in volcanism. The Neoproterozoic inherited zircons (850–725 Ma) are also preserved in the Cathaysia Block similar to the GHS (Li et al. Reference Li, Li and Li2005, Reference Li, Li, Li and Liu2008, Reference Li, Li and Li2010; Wang et al. 2010a,b). The bimodal magmatic and volcaniclastic rocks from the Cathaysia Block may be the source of these age groups of zircons in the GHS, because the ϵHf values of both regions are nearly similar to those of our study, ranging from −14.40 to ∼9.50.

The other prominent U–Pb ages of the migmatitic zircon are 649–498 Ma with ϵHf values of −16.8 to +3.6. These zircon U–Pb ages are most similar to those from the Yangtze and Cathaysia blocks, as also suggested by Wang & Zhou (Reference Wang and Zhou2012) and Spencer et al. (Reference Spencer, Dyck, Mottram, Roberts, Yao and Martin2019). Similarly, detrital zircon ages of 604, 553 and 527 Ma are also reported from the Greater Himalayan granite (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Thöni, Frank, Grasemann, Klötzli, Guntli and Draganits2001; Quigley et al. Reference Quigley, Liangjun, Gregory, Corvino, Sandiford, Wilson and Xiaohan2008; Mottram et al. Reference Mottram, Argles, Harris, Parrish, Horstwood, Warren and Gupta2014). These detrital zircons may be derived from these Himalayan granitic bodies. Several Palaeozoic granites intruded the Higher Himalayan Crystalline above the Main Central Thrust and adjacent to the STD (Singh et al. Reference Singh, Singhal and Das2020; Dhiman & Singh, Reference Dhiman and Singh2021). The North Himalayan gneissic domes lie above the STDS; similar granitic plutons are exposed within the dome-like Leo Pargil, Kangmar, Nyimaling, Lhago-Kangri, Tso-Morari, Kampa, Rupsu, Jispa, Gurla Mandhata, Kade, Ama Drime, Koksar and Kagan (Frank et al. Reference Frank, Gansser and Trommsdorff1977; Girard & Bussy, Reference Girard and Bussy1999; Singh et al. Reference Singh, Barley, Brown, Jain and Manickavasagam2002; Singh & Jain, Reference Singh and Jain2003; Jessup et al. Reference Jessup, Langille, Diedesch and Cottle2019).

The 604 Ma granite in Sikkim yielded zircon grains with 206/238 dates of 631, 770, 982, and 1850 Ma, so this granite contains inherited zircons that could explain the 650–605 Ma ages obtained in the studied samples. The late Neoproterozoic to early Cambrian dates obtained from the studied sample could be derived from (a) a larger range of ages of Himalayan 650–527 Ma granitic plutons and (b) scatter of 206/238 dates due to a range of ages in the source plutons (e.g. from inheritance) plus small amounts of lead loss during Cenozoic metamorphism.

The youngest age of the zircon protoliths is controlled by 550 to 470 Ma Himalayan granitic bodies (Cawood et al. Reference Cawood, Johnson and Nemchin2007). Such ages are likely derived from the Gondwana-forming orogenies and possibly derive from the proximal East African Orogen. This Neoproterozoic and early Palaeozoic zircon could have been derived from convergent-margin systems of the East African and Ross–Delamerian orogenies of Gondwana (DeCelles et al. Reference DeCelles, Gehrels, Quade, LaReau and Spurlin2000; Myrow et al. Reference Myrow, Hughes, Goodge, Fanning, Williams, Peng, Bhargava, Parcha and Pogue2010). The ϵHf values (−16.8 to +3.6) of the zircons are elevated, indicating derivation from isotopically depleted lithosphere. These Hf values are similar to the Ross Orogeny in Antarctica (Nelson & Cottle, Reference Nelson and Cottle2017, Reference Nelson and Cottle2018). Analogous U–Pb zircon ages of granites have been reported along the GHS above the Main Central Thrust from the Ama Drime granitic orthogneisses (Cottle et al. Reference Cottle, Jessup, Newell, Horstwood, Noble, Parrish, Waters and Searle2009) as well as from the Kangmar dome (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Hacker, Dinklage, Wang, Gans, Calvert, Wan, Chen, Blythe and McClelland2000) and the Kampa dome (Quigley et al. Reference Quigley, Liangjun, Gregory, Corvino, Sandiford, Wilson and Xiaohan2008) in southern Tibet. These data suggest a significant and prevalent crustal melting event along the Himalayan orogen during Ordovician time. According to Cawood et al. (Reference Cawood, Johnson and Nemchin2007), this episode is designated as the Bhimphedian Orogeny and has been related to the Cambrian formation of Gondwana (Yin et al. Reference Yin, Dubey, Kelty, Webb, Harrison, Chou and Célérier2010). The prolonged magmatism associated with the Bhimphedian Orogeny may reveal an oceanic arc complex (comprising the Lhasa and southern Qiangtang blocks and pre-c. 500 Ma arc-related rocks in the GHS) on the northern margin of India (Spencer et al. Reference Spencer, Dyck, Mottram, Roberts, Yao and Martin2019). The igneous activity during early Palaeozoic time within the Himalayan orogen matches in age with Gondwana-wide igneous activity.

It is challenging to differentiate local versus distant sources for early Palaeozoic detrital zircons. Our geochronological data and Hf isotopic data are consistent with a GHS origin, implying that the LPD migmatites are part of the GHS, not the THS. The lack of significant zircons of Cambrian–Ordovician or Palaeozoic age in our studied sample suggests that the migmatite rock from the LPD is unrelated to the THS.

7.d. Palaeogeographic reconstruction

The palaeogeography of tectonic models is typically constrained by the palaeomagnetic data and geological settings (Merdith et al. Reference Merdith, Collins, Williams, Pisarevsky, Foden, Archibald, Blades, Alessio, Armistead, Plavsa, Clark and Müller2017). The ϵHf data from the LPD are consistent with significant continental reworking. The ϵHf(t) values of zircons also provide evidence about the palaeogeography of the studied samples. Most of the detrital zircons observed from Proterozoic and Palaeozoic rocks throughout the Himalaya and Tibet are generally <1.4 Ga, with the maximum zircon grains in the range of 500 to 1200 Ma (DeCelles et al. Reference DeCelles, Gehrels, Quade, LaReau and Spurlin2000; Myrow et al. Reference Myrow, Hughes, Goodge, Fanning, Williams, Peng, Bhargava, Parcha and Pogue2010). The 1300–1100 Ma ages of zircons are consistent with it being part of the Rodinia supercontinent but lying on the outboard of East Antarctica (e.g. Li et al. Reference Li, Li, Li and Liu2008) and indicate that the studied zircons were derived from the Rodinia supercontinent. Most of our studied samples showed a prominent age peak between 800 and 500 Ma. The zircon ages of the LPD closely resemble the age distributions for blocks from East Gondwana (Eastern Ghats orogen), including the Yangtze and Cathaysia blocks. A similar age (∼900–600 Ma) igneous activity is observed from several parts of the Himalaya and different Tibetan terranes (Gehrels et al. Reference Gehrels, Kapp, DeCelles, Pullen, Blakey, Weislogel, Ding, Guynn, Martin, McQuarrie and Yin2011). These preserved igneous activities are inferred to be limited exposures of the arc-type basement that may be prevalent inside the Tibet–Himalaya orogen and may characterize a northeasterly extension of juvenile terranes in the Arabian–Nubian Shield (Stern et al. Reference Stern, Percival and Mortensen1994; Johnson & Woldehaimanot, Reference Johnson and Woldehaimanot2003).

The Eastern Ghats orogen is connected with the similar-aged Rayner province in Antarctica due to a similar tectonic and metamorphic history, proposing that the combined Rayner/Eastern Ghats complex grew as a result of the prolonged subduction on the eastern margin of India (Rickers et al. Reference Rickers, Mezger and Raith2001; Dobmeier & Raith, Reference Dobmeier and Raith2003; Mikhalsky et al. Reference Mikhalsky, Sheraton, Kudriavtsev, Sergeev, Kovach, Kamenev and Laiba2013). This long-drawn-out magmatism/metamorphism during early Tonian time functioned as proof of India’s incorporation with Rodinia (e.g. Li et al. Reference Li, Li, Li and Liu2008; Dasgupta et al. Reference Dasgupta, Bose and Das2013). There was a connection between South China and India in late Mesoproterozoic time, and this was preserved for the entire Neoproterozoic period (i.e. no relative motion between South China (Cathaysia Block and Yangtze craton) and India) (Cawood et al. Reference Cawood, Wang, Xu and Zhao2013). The Archaean–Palaeoproterozoic core of the Yangtze Block may have formed a microcontinental kernel for Tonian arc-accretion that collided with the Cathaysia Block at c. 860 Ma (Yao et al. Reference Yao, Cawood, Shu, Santosh and Li2016). This Yangtze Block core suggests that the accretionary record of South China is coeval with the accretionary history of NW India (Bhowmik et al. Reference Bhowmik, Bernhardt and Dasgupta2010, Reference Bhowmik, Wilde, Bhandari, Pal and Pant2012; Cawood et al. Reference Cawood, Wang, Xu and Zhao2013; Meert et al. Reference Meert, Pandit and Kamenov2013). The ϵHf(t) data (−14.4 to +9.5) of the 800–750 Ma zircons reveal the presence of the subduction zone at ∼800 Ma along the Yangtze margin and lateral development of subduction along the eastern Indian margin. This interpretation closely corresponds with the findings of Spencer et al. (Reference Spencer, Dyck, Mottram, Roberts, Yao and Martin2019).

The ϵHf(t) values (−16.6 to +3.5) for the 650–500 Ma zircons are similar to western Australia (part of Gondwana) and Tethyan Himalayan rocks, suggesting that these zircons were reworked mainly from the old continental crust. Our interpretations are consistent with these blocks having been close to Gondwana. The plentiful late Mesoproterozoic – early Neoproterozoic and middle Cambrian zircons are consistent with a Gondwanan origin (Duan et al. Reference Duan, Meng, Zhang and Liu2011). The late Neoproterozoic collision of East Gondwana (India, East Antarctica, Australia) with eastern Africa wedged the Indian craton amid the East Antarctic and African cratons. The northern margin of the Indian continent was consequently in a palaeogeographic position to receive zircons from, even though distant, mountain belts established during and proximately after the Gondwana assembly (Squire et al. Reference Squire, Campbell, Allen and Wilson2006; Cawood et al. Reference Cawood, Johnson and Nemchin2007; Myrow et al. Reference Myrow, Hughes, Goodge, Fanning, Williams, Peng, Bhargava, Parcha and Pogue2010), which may be the East African Orogen, comprising the juvenile Arabian–Nubian Shield, Kuunga–Pinjarra orogen and the outer part of the Ross–Delamerian orogeny as the East African Orogeny was active from c. 680 to 500 Ma. The Ross magmatic-arc activity had initiated by 580 Ma (Goodge et al. Reference Goodge, Myrow, Phillips, Fanning and Williams2004; Cawood, Reference Cawood2005) (Fig. 9). The penecontemporaneous igneous activity was observed in the GHS and within the Lhasa terrane, Qiangtang terrane and Amdo basement during early Palaeozoic time. These Palaeozoic arc-type igneous rocks along the northern margin of Gondwana can be inferred to be evidence of convergent-margin magmatism and tectonism (Cawood & Buchan, Reference Cawood and Buchan2007; Cawood et al. Reference Cawood, Johnson and Nemchin2007).

Fig. 9. Palaeogeographic reconstruction of eastern Gondwana c. 500 Ma (after Torsvik & Cocks, Reference Torsvik and Cocks2009; Myrow et al. Reference Myrow, Hughes, Goodge, Fanning, Williams, Peng, Bhargava, Parcha and Pogue2010) and age of various terranes. Ab – Alborz terrane; Afg – Afghan terranes; San – Sanand terrane; Mad – Madagascar.

Evidence for the Cambro-Ordovician Bhimphedian Orogeny related to Gondwana effects can be found from Pakistan to the eastern part of the Himalaya (Cawood et al. Reference Cawood, Johnson and Nemchin2007). The basaltic and andesitic volcanism is related to the magmatic arc, active from 530 to 490 Ma. The activity of the magmatic arc was imbricated by regional deformation, anatectic processes and emplacement of a granite pluton (S-type) that was protracted prior to 470 Ma. It may be possible that the zircon grains with an age of ∼500 Ma were mostly sourced from the prevalent granite occurrences all over the Himalaya and in numerous sections around Gondwana (Debon et al. Reference Debon, LeFort, Sheppard and Sonet1986; LeFort et al. Reference LeFort, Debon, Pêcher, Sonet and Vidal1986).

8. Conclusions

-

(1) Zircon U–Pb dating of migmatite from the upper Sutlej valley (Leo Pargil region) indicates that the zircon crystallized at c. 1100–1000 Ma. These zircons were likely linked to the assembly of the Rodinia supercontinent.

-

(2) The Greater Himalayan and/or Aravalli 930–800 Ma igneous rocks, related to the presently exposed rocks, could have been exposed at the Earth’s surface at the time of deposition of the (meta)sedimentary rocks and thus could have provided sediment to the GHS.

-

(3) The other prominent U–Pb age peak of detrital zircons (649–498 Ma) with ϵHf(t) values of −16.8 to +3.6 demonstrates that they are sourced from Gondwana with a possible source being the East African Orogen, Western Australia, Cathaysia and the Yangtze blocks.

-

(4) Ordovician ages preserved in migmatite are likely related to the Bhimphedian Orogeny.

-

(5) The late Neoproterozoic to Ordovician detrital zircon could be obtained from Greater Himalayan magmatic sources.

-

(6) We conclude that all the detrital zircons in our samples can be derived from local sources.

-

(7) Partial melting occurred between 30 and 15 Ma, identical to other Himalayan migmatites. The limited variation of ϵHf(t) values in the zircons might reflect restricted degrees of mixing between outside Hf from external melt and internal Hf from dissolution–reprecipitation of inherited zircon.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756822000449

Acknowledgements

This paper represents a part of the Ph.D. work carried out by Shashi Ranjan Rai. Shashi Ranjan Rai is thankful to CSIR for a financial grant in the form of a research fellowship. The authors are grateful to M. J. Kohn for reviewing the draft of the manuscript, which greatly enhanced the quality of the manuscript. S.R.R. is highly thankful to Prof. Aaron J. Martin and an anonymous reviewer for their comprehensive review and helpful comments and Dr Sarah Sherlock for her editorial comments, which substantially improved the manuscript. All authors are thankful to the director of the Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology, Dehradun, and the head of the Department of Earth Sciences, IIT Roorkee, for providing lab facilities and encouragement to carry out this work. The GeoHistory Facility instruments in the John de Laeter Centre, Curtin University, were funded via an Australian Geophysical Observing System grant provided to AuScope Pty Ltd by the AQ44 Australian Education Investment Fund programme. The NPII MC-ICP-MS was obtained via funding from the Australian Research Council LIEF programme (LE150100013).

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.