1. Introduction

In late- to post-Variscan times, the European Variscan chain collapsed (Arthaud & Matte, Reference Arthaud and Matte1977; Ziegler, Reference Ziegler1990, Reference Ziegler, Selley, Cocks and Plimer2005). Subsiding depositional areas were ruled by the main tectonic shear zones (Elter et al. Reference Elter, Gaggero, Mantovani, Pandeli and Costamagna2020 and references therein). These areas developed throughout the chain, starting as narrow wrench basins and gradually evolving to full extensional basins over time (Arthaud & Matte, Reference Arthaud and Matte1977; Schneider & Romer, Reference Schneider, Romer, Linnemann and Romer2010; Schäfer, Reference Schäfer2011; Costamagna, Reference Costamagna2019). Alluvial to lacustrine deposition took place, so delineating complex terrestrial depositional systems; they usually showed an endorheic pattern (e.g. Provence: Durand, Reference Durand, Lucas, Cassinis and Schneider2006, Reference Durand2008; Saar-Nahe, Schäfer, Reference Schäfer2011; Sardinia, Costamagna, Reference Costamagna2019, Reference Costamagna2021 a). These basins were designed as molassic or molassoid basins. The molasse lithofacies are ‘clastic wedges laid down in shallow marine to non-marine environments adjacent to rising mountain chains’ (Van Houten, Reference Van Houten1973). They are mainly made by sediments removed from the developing mountain chain by erosion; this is typical for foreland basins (e.g. Van Houten, Reference Van Houten1973; Turner, Reference Turner1980; Van der Weil et al. Reference Van der Weil, Van den Berg and Hebeda1992). The molasse facies is composite; in fact, it is mainly built of conglomerates and sandstones, while other lithotypes such as marls, carbonates, shales and coals are subordinate. They result principally from the dismantling of the mountain ranges during and immediately after the paroxysmal orogenic phase. The molasse facies is generally, saving rare occurrences, not tectonized. Presently the molasse concept has been replaced by a two-phase model of foreland sedimentation (proximal versus distal part of the foreland basin: Heller et al. Reference Heller, Angevine, Winslow and Paola1988) or by the proforeland and retroforeland basin model (in Miall, Reference Miall2000); nonetheless it is still used (Einsele, Reference Einsele1992; Averbuch et al. Reference Averbuch, Mansy, Lamarche, Lacquement and Hanot2004; Dostal et al. Reference Dostal, Mueller and Murphy2004; Killias et al. Reference Kilias, Vamvaka, Falalakis, Sfeikos, Papadimitriou, Gkarlaouni and Karakostas2013; Zaghdoudi et al. Reference Zaghdoudi, Kadri, Alayet, Bounasri, Essid and Gasmi2021) and it is considered still valid. Thus, the Mulargia–Escalaplano molassic basin deserved a sedimentary analysis in such a sense.

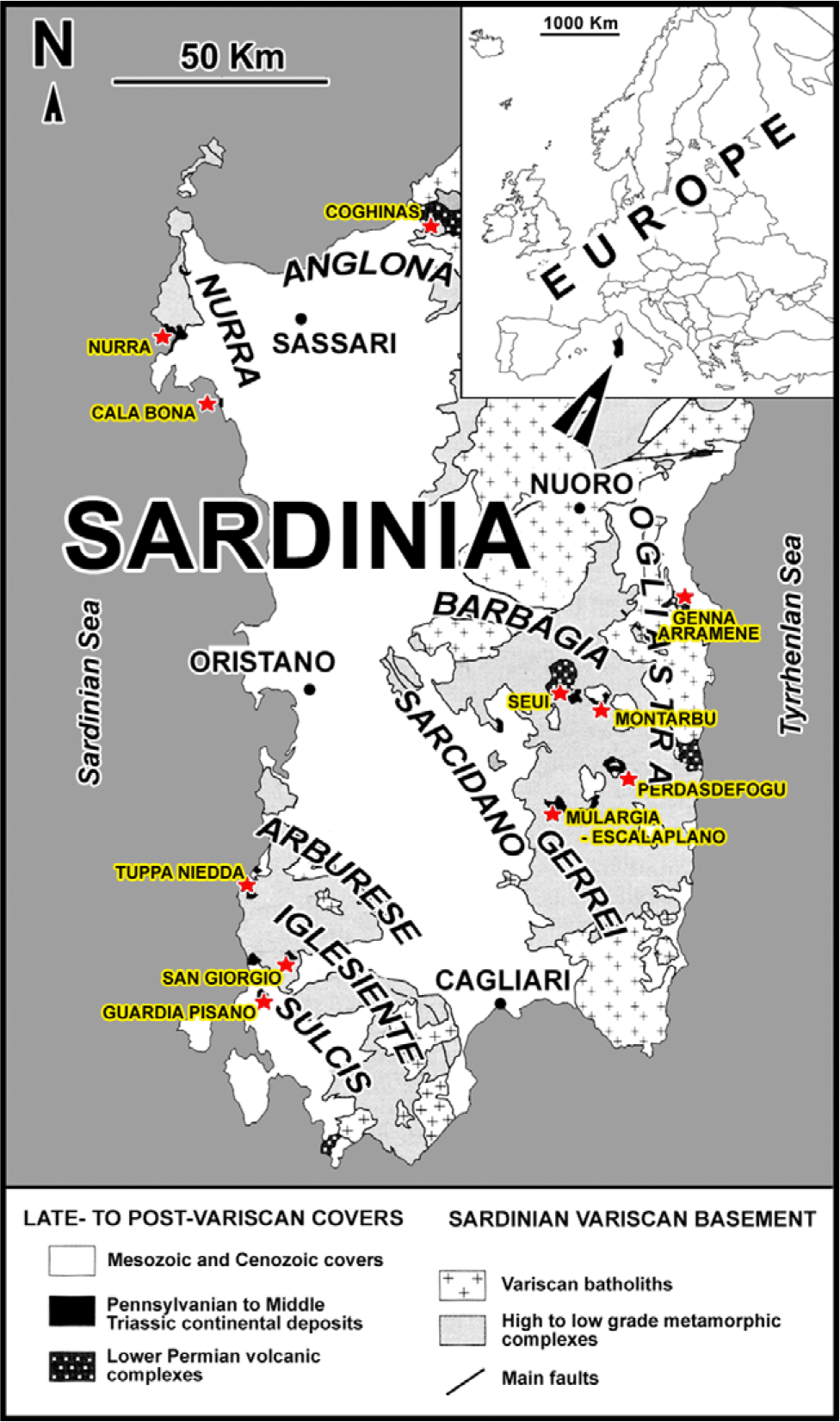

In Sardinia, the post-paroxysmal Variscan basins (Fig. 1) are defined as molassic (Costamagna, Reference Costamagna2019 and references therein). Usually, the conditions of their outcrops do not allow the visual inference of the relationships between their superposed sedimentary fillings. Consequently, the relationships in the field remain somewhat hypothetical. The previous investigations on the molassic Mulargia–Escalaplano basin in the Southern Variscan Realm gave only a general framework of the succession (Vardabasso, Reference Vardabasso1966; Pecorini, Reference Pecorini1974; Barca et al. Reference Barca, Carmignani, Eltrudis and Franceschelli1995; Cassinis et al. Reference Cassinis, Cortesogno, Gaggero, Pittau, Ronchi and Sarria2000; Barca & Costamagna, Reference Barca and Costamagna2005; Ronchi et al. Reference Ronchi, Sarria and Broutin2008; Costamagna, Reference Costamagna2019, Reference Costamagna2021 b). Repeated field surveys discovered new outcrops and provided new data.

Fig. 1. Localization of the main outcrops of the late to post-Variscan molassic basins in Sardinia.

The scope of this paper is to describe in detail the sedimentology, the depositional environments and the geological evolution over time of the Upper Pennsylvanian to lower–middle? Permian molassic succession (Francavilla et al. Reference Francavilla, Cassinis, Cocozza, Gandin, Gasperi, Gelmini, Rau, Tongiorgi and Vai1977; Pittau et al. Reference Pittau, Del Rio and Funedda2008) of the Mulargia–Escalaplano basin in Southern Sardinia. This has been accomplished by assembling unedited field stratigraphic and sedimentological data from new detailed surveys and (re)interpreting previously published data. This molassic basin is the only one in the Southern Variscan Realm (sensu Rossi et al. Reference Rossi, Oggiano and Cocherie2009) where relationships and superposition between the several depositional cycles from the Late Pennsylvanian to early Middle Triassic period can be directly observed. Therefore, this investigation can help shed light on (a) the sedimentary evolution, (b) the ruling factors, (c) the tectonosedimentary relationships and (d) the relative age of the superposed filling sequences of an ancient molassic intramontane (Vai, Reference Vai2003) or intermontane basin (Schneider & Romer, Reference Schneider, Romer, Linnemann and Romer2010) in this sector of the collapsing Variscan chain. Based on the newly described data, an improved organization of the stratigraphic framework of the basin has been implemented. A final assessment of stratigraphic, magmatic and radiometric data from all the Sardinian late- to post-Variscan molassic basins and from some of the European coeval basins revealed itself to be useful in evaluating the overall European stratigraphic framework.

2. Geological setting

2.a. General context of the molassic basins in Sardinia

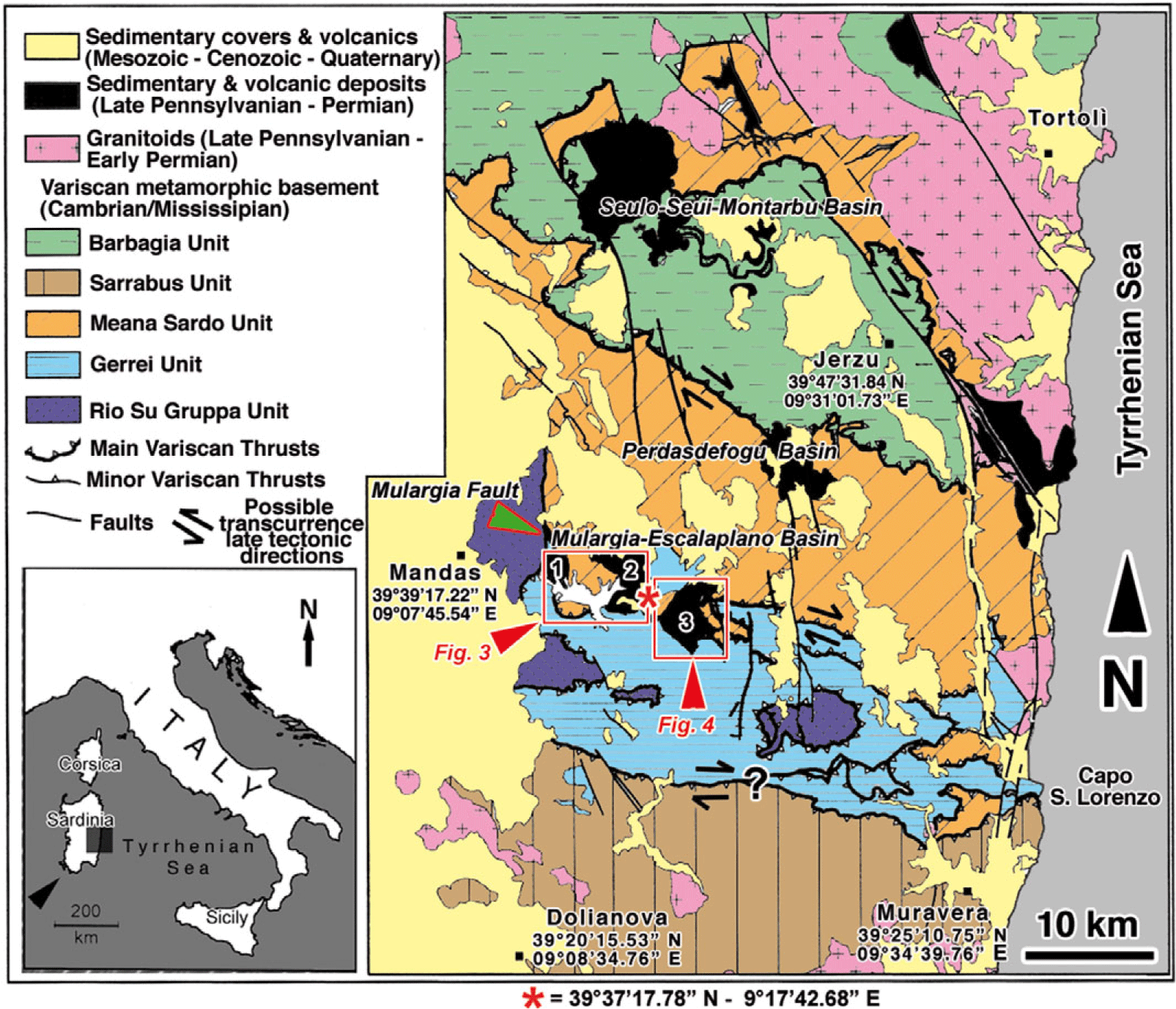

Following the Variscan orogenesis (Carmignani et al. Reference Carmignani, Carosi, Di Pisa, Gattiglio, Musumeci, Oggiano and Pertusati1994), in Sardinia several basins developed unconformably over the Variscan basement along major tectonic discontinuities (Carmignani et al. Reference Carmignani, Oggiano, Barca, Conti, Eltrudis, Funedda, Pasci and Salvadori2001). Possibly these discontinuities were Variscan thrust surfaces later reactivated as transcurrent faults (Fig. 2) (Ziegler & Stampfli, Reference Ziegler and Stampfli2001; Perotti & Cassinis, Reference Perotti and Cassinis2006). In these basins, limited late-orogenic transpressive movements have been pointed out that occurred during Late Pennsylvanian to early Permian times (Sarria & Serri, Reference Sarria and Serri1986; Barca et al. Reference Barca, Costamagna, Janssen and Von Der Handt2001; Cassinis et al. Reference Cassinis, Cortesogno, Gaggero, Ronchi, Sarria, Serri and Calzia2003). These basins were filled with clastic and minor carbonate deposits during Late Pennsylvanian to early–middle? Permian times (Carmignani et al. Reference Carmignani, Carosi, Di Pisa, Gattiglio, Musumeci, Oggiano and Pertusati1994; Cassinis et al. Reference Cassinis, Cortesogno, Gaggero, Pittau, Ronchi and Sarria2000; Aldinucci et al. Reference Aldinucci, Dallagiovanna, Durand, Gaggero, Martini, Pandeli, Sandrelli and Tongiorgi2006; Costamagna, Reference Costamagna2019). They were the consequence of the collapse of the local branch of the Variscan mountain chain connected with a right-lateral mega-shear system superimposed on the Variscan mega-suture (Vai, Reference Vai1991, Reference Vai1997, Reference Vai2003; Ziegler, Reference Ziegler, von Raumer and Neubauer1993; Ziegler & Stampfli, Reference Ziegler and Stampfli2001; Muttoni et al. Reference Muttoni, Kent, Garzanti, Brack, Abrahamsen and Gaetani2003, Reference Muttoni, Gaetani, Kent, Sciunnach, Angiolini, Berra, Garzanti, Mattei and Zanchi2009; Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Nance and Cawood2009; Gutierrez-Alonso et al. Reference Gutiérrez-Alonso, Fernández-Suárez, Jeffries, Johnston, Pastor-Galán, Murphy, Franco and Gonzalo2011; Elter et al. Reference Elter, Gaggero, Mantovani, Pandeli and Costamagna2020). These basin fills were the result of two superposed main depositional cycles (Cassinis & Ronchi, Reference Cassinis and Ronchi2002; Barca & Costamagna, Reference Barca and Costamagna2006 a; Costamagna & Barca, Reference Costamagna and Barca2007; Elter et al. Reference Elter, Gaggero, Mantovani, Pandeli and Costamagna2020) possibly related to different tectonic regimes (Costamagna, Reference Costamagna2019; Elter et al. Reference Elter, Gaggero, Mantovani, Pandeli and Costamagna2020). The main depositional cycle starting in Early?–Middle Triassic time in Sardinia can be related to the opening of the Neo-Tethys (Costamagna & Barca, Reference Costamagna and Barca2002; Costamagna, Reference Costamagna2012; Baucon et al. Reference Baucon, Ronchi, Felletti and Neto de Carvalho2014; Elter et al. Reference Elter, Gaggero, Mantovani, Pandeli and Costamagna2020).

Fig. 2. Geological framework of central Sardinia with the location of the late- to post-Variscan basins and the different outcropping areas of the investigated Mulargia–Escalaplano basin (Sardinia, Italy): (1) the Western Mulargia sector, (2) the Eastern Mulargia sector, and (3) the Escalaplano sector. Modified from Carmignani et al. (Reference Carmignani, Oggiano, Barca, Conti, Eltrudis, Funedda, Pasci and Salvadori2001).

Barca & Costamagna (Reference Barca and Costamagna2006 a) and Costamagna & Barca (Reference Costamagna and Barca2007), relying on new surveys and on previous studies (Sarria & Serri, Reference Sarria and Serri1986; Barca et al. Reference Barca, Costamagna, Janssen and Von Der Handt2001; Cassinis et al. Reference Cassinis, Cortesogno, Gaggero, Ronchi, Sarria, Serri and Calzia2003), distinguished in Sardinia at least two main superposed Upper Pennsylvanian–Permian molassic successions, weakly deformed and undeformed, respectively. Those successions are followed in turn by unconformable early-Alpine or post-molassic successions. Sardinia in Early – early Middle Triassic time experienced early extensional tectonics of the Alpine cycle, which ultimately triggered the Neo-Tethys opening (Bernoulli & Jenkyns, Reference Bernoulli, Jenkyns, Dott and Shaver1974; Stampfli & Marchant, Reference Stampfli, Marchant, Pfiffner, Lehner, Heitzmann, Mueller and Steck1997). Frequently, those overlapping continental successions are superimposed unconformably on each other (Costamagna, Reference Costamagna2019), suggesting intervals of tectonic activity. Usually, the youngest successions are also the largest (Costamagna, Reference Costamagna2021 a); they are probably related to the same reactivated main Variscan discontinuities (Elter et al. Reference Elter, Gaggero, Mantovani, Pandeli and Costamagna2020).

The first depositional cycle, Kasimovian to Sakmarian in age (Pittau et al. Reference Pittau, Del Rio and Funedda2008; partially corresponding to the ‘Autuniano sardo’ of Ronchi et al. Reference Ronchi, Sarria and Broutin2008), is related to the late Variscan successions. It consists of ‘limnic’ (so historically defined by the Authors), coarse- to fine-grained, dark sediments deposited during a wet and warm climate (microflora, Pittau et al. Reference Pittau, Del Rio and Funedda2008; organic matter-rich deposits, Costamagna, Reference Costamagna2019). The second Saxonian depositional cycle (post-Sakmarian to Capitanian) (Ronchi et al. Reference Ronchi, Sarria and Broutin2008) is post-Variscan, and conformably to unconformably overlies the first cycle. It includes red bed coarse- to fine-grained sediments deposited under a dry to hot climate (microflora, Pittau et al. Reference Pittau, Del Rio and Funedda2008; inorganically derived carbonates and evaporites, Costamagna, Reference Costamagna2019). Information about the climate of the area was also given by Boucot et al. (Reference Boucot, Xu and Scotese2013).

2.b. The Mulargia–Escalaplano basin

The Upper Pennsylvanian–Permian succession of the Mulargia–Escalaplano basin crops out in the Gerrei area of central Sardinia (Barca et al. Reference Barca, Carmignani, Eltrudis and Franceschelli1995; Cassinis et al. Reference Cassinis, Cortesogno, Gaggero, Pittau, Ronchi and Sarria2000; Barca & Costamagna, Reference Barca and Costamagna2005) (Figs 1, 2). The sedimentary basin consists of two adjacent sectors: the Mulargia sector in the NW (Figs 2, 3) and the Escalaplano sector in the SE (Figs 2, 4). They are separated by a structural Cenozoic high built of Variscan basement rocks; this high probably developed in Palaeogene to Quaternary times due to late extensional tectonics that subsided the SE part of the Late Pennsylvanian–Permian basin (Pecorini, Reference Pecorini1974). The Mulargia and Escalaplano sectors of the basin were initially treated as distinct basins (Cavinato & Beneo, Reference Cavinato and Beneo1959; Vardabasso, Reference Vardabasso1966). Later, the close stratigraphic and sedimentological relationship of the Mulargia and Escalaplano upper Palaeozoic succession allowed them to be considered as a single basin with only small, consequential sedimentary differences from one part to another (Pecorini, Reference Pecorini1974; Cassinis et al. Reference Cassinis, Cortesogno, Gaggero, Pittau, Ronchi and Sarria2000; Barca & Costamagna, Reference Barca and Costamagna2005; Costamagna, Reference Costamagna2019).

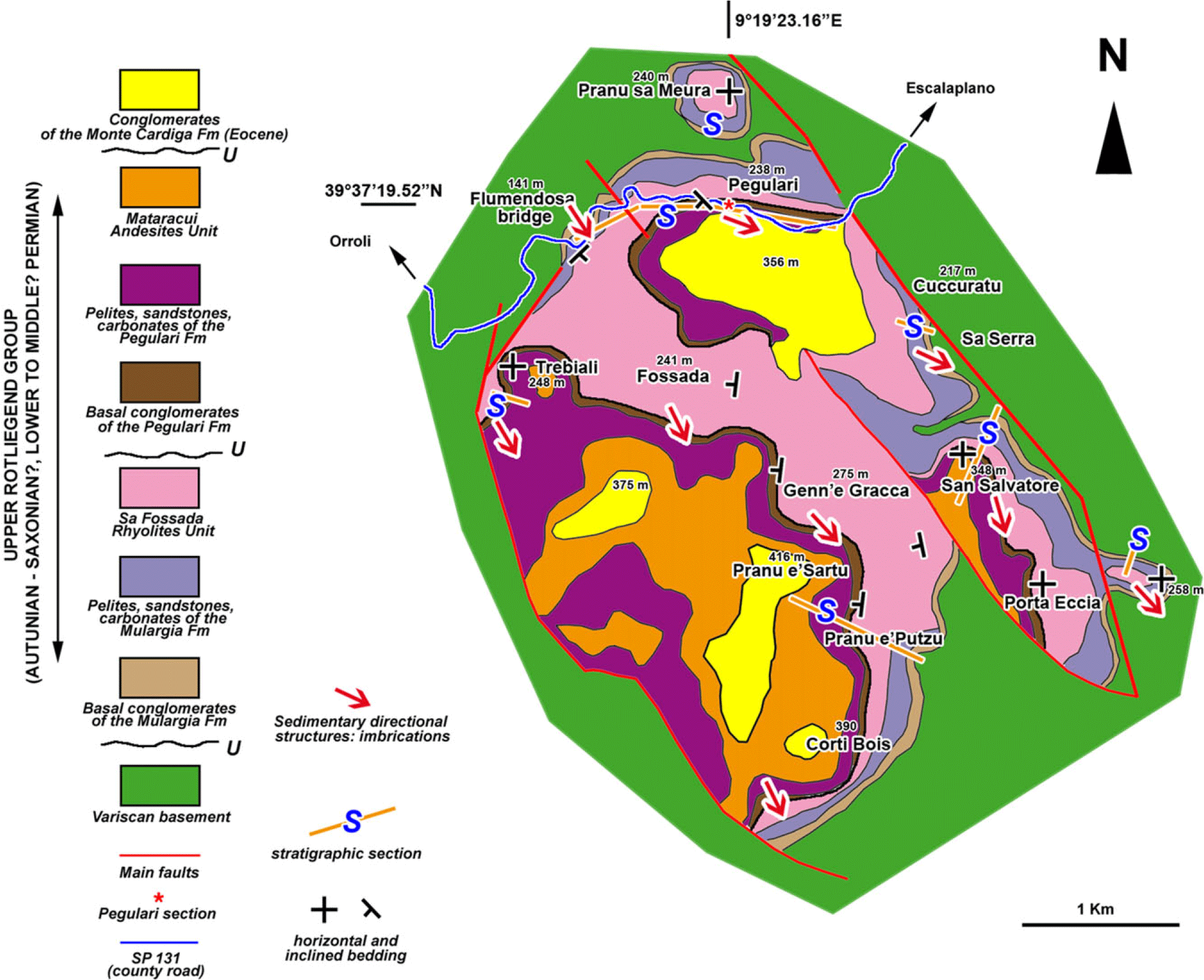

Fig. 3. Geological map of the Late Pennsylvanian – early–middle? Permian Mulargia–Escalaplano basin in the Mulargia sector.

Fig. 4. Geological map of the Late Pennsylvanian – early–middle? Permian Mulargia–Escalaplano basin in the Escalaplano sector. Redrawn and modified from Ronchi in Cassinis et al. (Reference Cassinis, Cortesogno, Gaggero, Pittau, Ronchi and Sarria2000).

In the Mulargia–Escalaplano basin, both the lower ‘limnic’ succession and the upper red bed succession occur (Barca & Costamagna, Reference Barca and Costamagna2005). Each of them has been related generally to continental environments whose fining-upward trend was interpreted as gradually decreasing energy related to the progressive dismantling of the Variscan chain (Barca & Costamagna, Reference Barca and Costamagna2005). They show periodic climaxes of volcano-tectonic activity. In the Escalaplano sector, a lower and an upper ‘volcanic and sedimentary succession’ (Cassinis et al. Reference Cassinis, Cortesogno, Gaggero, Pittau, Ronchi and Sarria2000) have been evidenced as informal stratigraphic units. In contrast, in the Mulargia sector, four sedimentary and volcano-sedimentary lithostratigraphic units have been differentiated (Barca & Costamagna, Reference Barca and Costamagna2005). An Upper Pennsylvanian to Permian Rio Su Luda Formation, putting together ‘limnic’ and red bed successions alike, was proposed (Pertusati et al. Reference Pertusati, Sarria, Cherchi, Carmignani, Barca, Benedetti, Chighine, Cincotti, Oggiano, Ulzega, Orru and Pintus2002; Ronchi & Falorni, Reference Ronchi and Falorni2004; Ronchi et al. Reference Ronchi, Sarria and Broutin2008). Costamagna (Reference Costamagna2019, Reference Costamagna2021 b) based on lithostratigraphic and sedimentological grounds, separated the upper red bed Mulargia Formation pertaining to the Upper Rotliegend Group from the lower ‘limnic’ Rio Su Luda Fm of the Lower Rotliegend Group. Nonetheless, a detailed stratigraphic correlation between the Mulargia Lake and Escalaplano basin sectors is still needed (Ronchi et al. Reference Ronchi, Sarria and Broutin2008).

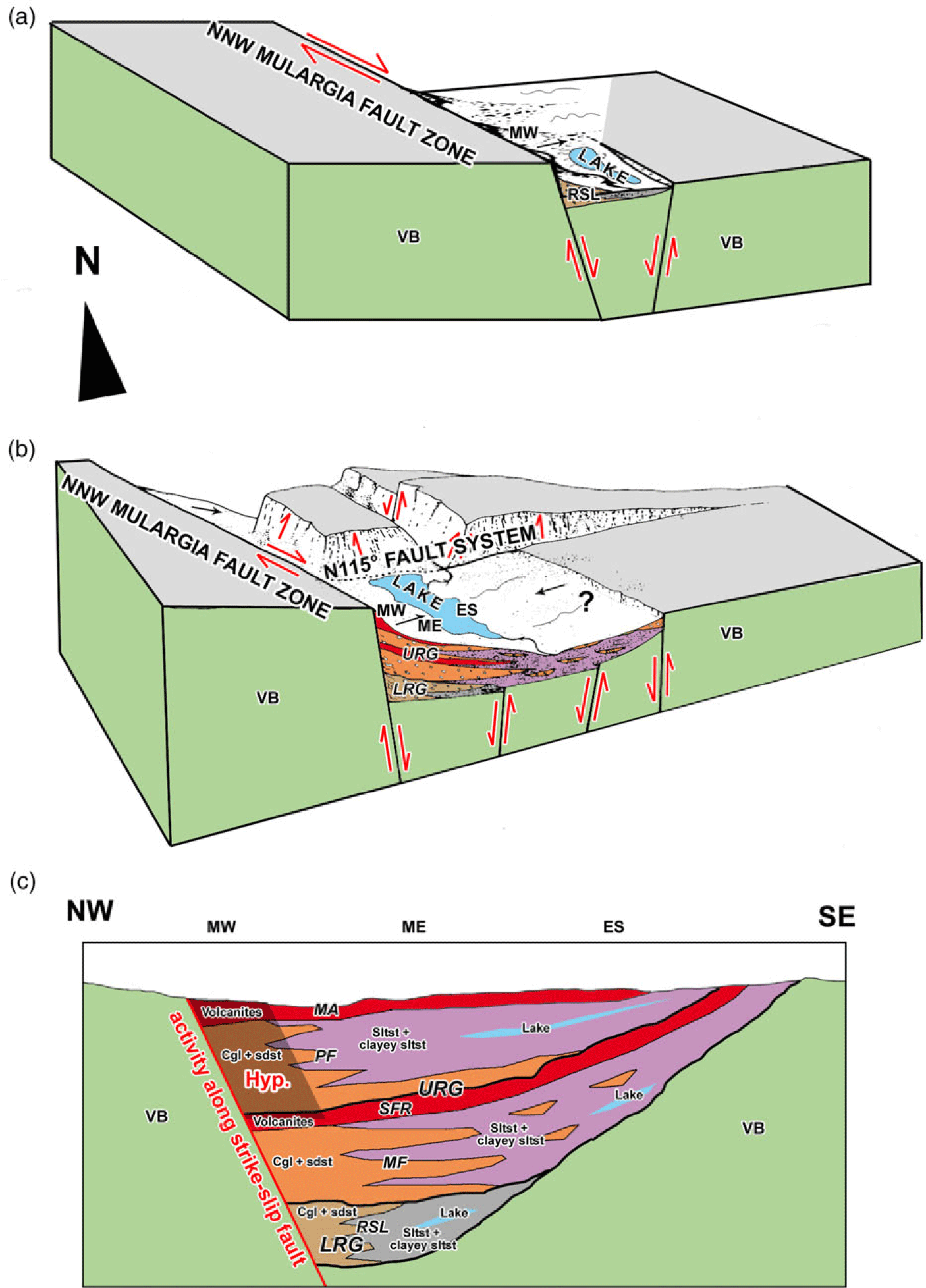

Different hypotheses have been proposed relating to the tectonic control of the Mulargia–Escalaplano molassic basin: based on field surveys, Barca et al. (Reference Barca, Carmignani, Eltrudis and Franceschelli1995) considered that sedimentation was related to late listric-normal faults, whereas Cassinis et al. (Reference Cassinis, Cortesogno, Gaggero, Pittau, Ronchi and Sarria2000) considered that all the late Variscan basins were linked to strike-slip tectonics. Funedda et al. (Reference Funedda, Carmignani, Pasci, Patta, Uras, Conti and Sale2006, Reference Funedda, Carmignani, Pertusati, Uras, Pisanu and Murtas2008) instead found no field evidence of such listric faults and assumed that the Mulargia–Escalaplano basin was a tectonic lowland, fitting with a late Variscan synform, bounded by low-angle normal faults. In this view, the depositional area of the molassic basins was confined to small lows coinciding with structural synforms formed during post-collisional extension of the Sardinian Variscan orogen. Elter et al. (Reference Elter, Gaggero, Mantovani, Pandeli and Costamagna2020) associated the evolution of all late- to post-Variscan collapse basins with strike-slip tectonics related to intracontinental shear zones crossing the southern European Variscides. They hypothesized that this tectonic setting controlled the subsequent evolution of the Late Pennsylvanian to Middle Triassic palaeogeography. Evolutionary tectonosedimentary models for several of these basins, involving transtensive–transpressive mechanisms and extensional tectonics, have been proposed in Sardinia (Barca et al. Reference Barca, Carmignani, Eltrudis and Franceschelli1995; Barca & Costamagna, Reference Barca and Costamagna2003; Funedda et al. Reference Funedda, Carmignani, Pertusati, Uras, Pisanu and Murtas2008) and in western Europe (Toutin-Morin & Bonijoly, Reference Toutin-Morin and Bonijoly1992; Châteauneuf & Farjanel, Reference Châteauneuf and Farjanel1989; Lopez et al. Reference Lopez, Gand, Garric, Körner and Schneider2008; Schäfer, Reference Schäfer2011).

3. Materials and methods

In the Mulargia–Escalaplano basin (Fig. 2), covering an area ∼40 km2 wide, reconnaissance surveys were implemented to find new well-preserved outcrops and new stratigraphic sections worthy of description, sampling and comparison with the previously known outcrops and successions. The stratigraphic sections described by previous authors in the different sectors of the basin (Cassinis et al. Reference Cassinis, Cortesogno, Gaggero, Pittau, Ronchi and Sarria2000; Barca & Costamagna, Reference Barca and Costamagna2005) have been revised with particular regard to their sedimentological features. Additionally, new ones have been characterized and described. Texture, sorting and grain size have been visually evaluated by hand lens, also by using Swanson’s (Reference Swanson1981) comparative tables. Lithofacies observations have been undertaken in all areas on previously known and newly found outcrops. Individual facies were identified in the field; underlying and overlying facies were demarcated considering their sedimentological attributes such as lithology, texture and sedimentary structures, and then several lithological columns were prepared. For an immediate sedimentological approach, in the stratigraphic columns the siliciclastic lithofacies have been referred to Miall’s codes (Reference Miall1996) (Table 1) by using an updated version from Costamagna (Reference Costamagna2018) based substantially on Miall (Reference Miall, Walker and James1992, Reference Miall1996) and on Bridge’s (Reference Bridge1993) criticisms. The facies codes have then been grouped to form fluvial architectural elements and then used to hypothesize the fluvial styles by following Miall’s tables and concepts (Reference Miall1996, Reference Miall, James and Dalrymple2010) (Tables 2, 3). The main numeric parameters and features of the sedimentary bodies were collected and entered in tables (Table 4). The decline of the mean grain size both upwards and sideways has been used to add plausibility to the smoothing of the reliefs and to the direction of current flow (Table 4) (Pettijohn, Reference Pettijohn1975). Since the investigated basin is rich in conglomerate deposits, mainly imbrication structures and long a-axis pebble orientations have been collected for palaeodirectional purposes, besides rarer channel axes, ripple crests, cross-bedding, flute- and groove casts (Fig. 27; Table 5). The value of the measurement of the orientation of imbricated clasts in investigating the basin palaeocurrent direction, and, on the whole, of the basin development direction, has been emphasized by several authors (Potter & Pettijohn, Reference Potter and Pettijohn1963; Pettijohn, Reference Pettijohn1975; Lindholm, Reference Lindholm1987; Tucker, Reference Tucker2001; Stow, Reference Stow2005; Collinson et al. Reference Collinson, Mountney and Thompson2006). The value of the elongated axis measurement in regular flow rivers with steep slopes is supported by Reineck & Singh (Reference Reineck and Singh1980). The single data listed (Table 5) are the average of three measurements. Rose diagrams for evidence of the main measured directional structures were plotted (Fig. 27). The tilting effect from the directional linear and planar structures with a structural dip exceeding 10° has been removed by using stereographic projections (Lindholm, Reference Lindholm1987; Stow, Reference Stow2005; Tucker, Reference Tucker2011). They were of further help in the lithofacies interpretation.

Table 1. Update of Miall’s lithofacies classification by integrating Bridge’s palaeoenvironmental criticism and some additions (from Costamagna, Reference Costamagna2018, based on Miall, Reference Miall, Walker and James1992, Reference Miall1996; Bridge, Reference Bridge1993)

Table 2a. Basic classification of the within-channel and overbank architectural elements in fluvial deposits (from Miall, Reference Miall, James and Dalrymple2010)

See Table 1 for facies symbol descriptions.

Table 2b. Clastic architectural elements of the overbank environment (from Miall, Reference Miall, James and Dalrymple2010)

See Table 1 for lithology symbol descriptions.

Table 3. Architectural characteristics of some common fluvial styles (simplified from Miall, Reference Miall1996)

* CH element not differentiated, but present on a variety of scales in all examples. Elements shown in brackets are minor. See Table 2 for explanation of elements.

Table 4. Synthesis of the sedimentological features of the formational units from the Upper Pennsylvanian–Permian Mulargia–Escalaplano basin

Abbreviations: Cgl – conglomerate; Sdst/Siltst – sandstone/siltstone; Cl. Siltst – clayey siltstone.

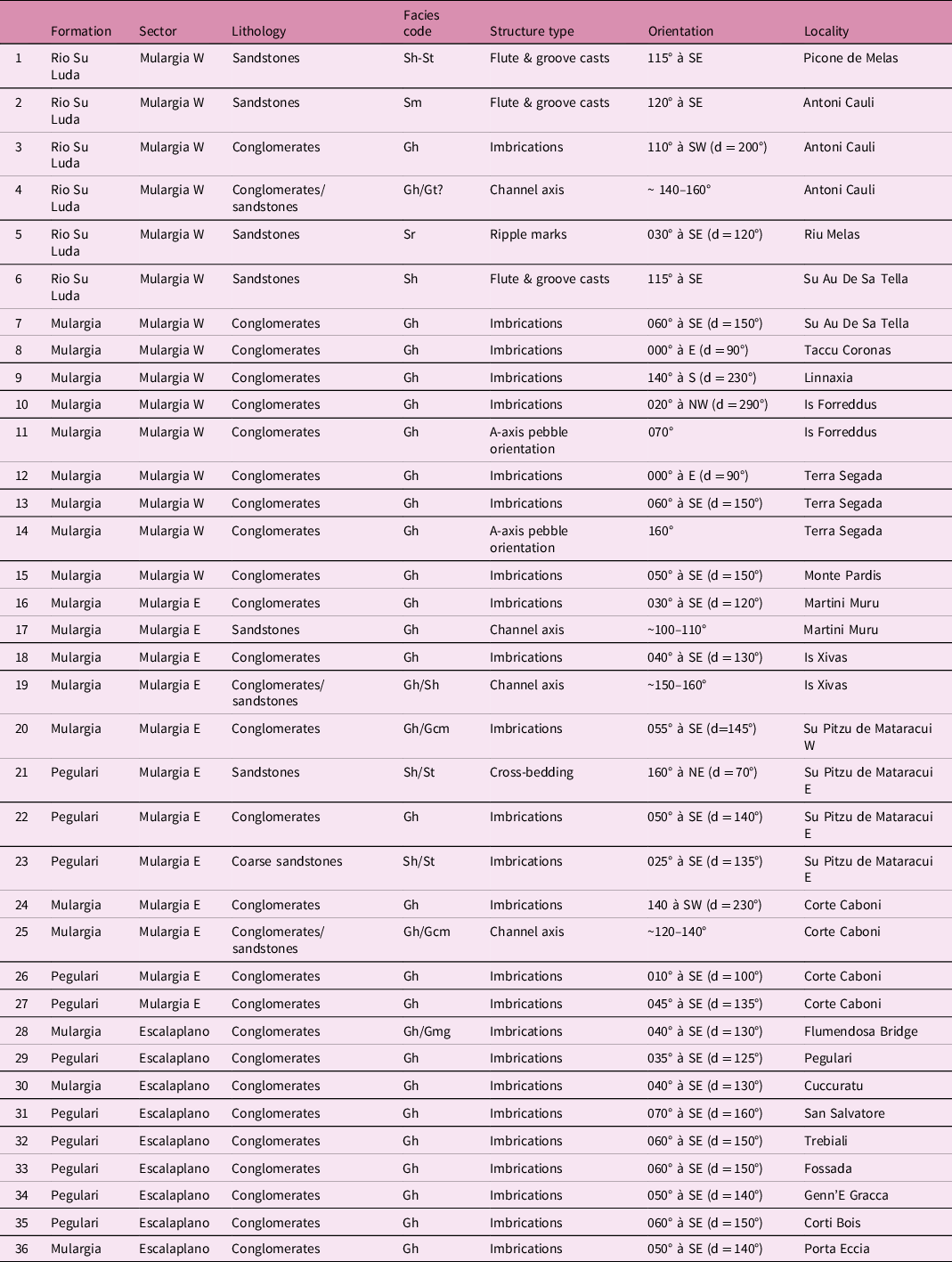

Table 5. Measurements of the directional data from the formational units of the Pennsylvanian–Permian Mulargia–Escalaplano basin

Measured parameters: (a) structure crest direction (ripple); (b) bulge direction (flute marks); (c) elongation directions (groove and tool marks); (d) intermediate b-axis of the imbricated pebble; (e) long a-axis of pebble where the imbrication was not evident. Facies codes as in Costamagna (Reference Costamagna2018), modified from Miall (Reference Miall, Walker and James1992, Reference Miall1996) considering Bridge’s (Reference Bridge1993) suggestions. Each noted value is the average of at least three measurements. See Table 1 for facies code descriptions.

Special attention has been given to the analysis of the macro- and microfacies of the carbonate intercalations to define their environmental value in the reconstructed basin lowland areas. Some dislodged carbonate blocks found close to the outcrops, clearly belonging to the successions and showing magnificently exposed sedimentological features, were also collected. The sampling was prevalently concentrated on the collection of carbonate lithofacies for the analysis in thin-sections under polarizing and palaeontological microscopes.

Petrographic modal analysis of the siliciclastic rock (of which we will disclose here only some strictly necessary glimpses) was also performed to give further insights into the geological framework (Costamagna et al. in prep.). Unaltered samples of the sandstones were collected from exposed stratigraphic sections. The sampled sandstones (chosen by sampling sandstones of similar grain size when it was possible) were used in thin-section preparation for petrographic study, on which a framework modal classification has been operated. For every thin-section, 300 points were considered for the point-counting method. Modal analysis was carried out again with the help of ImageJ Analysis software followed by visual double-checking. Data recalculation was made following the QFR method (Folk, Reference Folk1974, Reference Folk1980) and the Gazzi-Dickinson QFL point-counting method (Dickinson, Reference Dickinson1970; Dickinson et al. Reference Dickinson, Breard, Brakenridge, Erjavec, Ferguson, Inman, Knepp, Lindberg and Ryberg1983; Zuffa, Reference Zuffa and Zuffa1985) to minimize the dependence of rock composition on grain size (Ingersoll et al. Reference Ingersoll, Bullard, Ford, Grimm, Pickle and Sares1984; Zuffa, Reference Zuffa and Zuffa1985).

In the end, interpolations, extrapolations (sensu Schumm, Reference Schumm1991) and lithostratigraphic observations and correlations were made by using grouped data from outcrops and stratigraphic columns for an overall reconstruction of the basin filling and its evolution. Extended bibliographic research was carried out to compare the collected data with the stratigraphy, the sedimentology, the age, the depositional models and the tectonosedimentary evolution of the late- to post-Variscan basins of continental western Europe.

4. Stratigraphy and sedimentology of the Mulargia–Escalaplano basin: results

4.a. Lithofacies description and sedimentological data

4.a.1. Lower Rotliegend Group: Rio Su Luda Fm

In the NW part of the Mulargia sector (Figs 3, 5), a ∼60 m thick ‘limnic’ succession (Fig. 6a) pertaining to the Rio Su Luda Fm of the Lower Rotliegend Group crops out (Figs 7, 8). It dips 25°/30° to the WSW; its inclination decreases slowly upwards. Unconformably above the Silurian black schists of the Variscan basement, the Rio Su Luda Fm starts with alternations of metre-thick petromict conglomeratic breccias, microbreccias and coarse sandstones made up of centimetre- to millimetre-sized angular to subangular quartz and metamorphic blade-shaped rock pebbles embedded in a blackish sandy to silty-clayey matrix (Fig. 6b, c). Frequently the pebbles are imbricated (Table 5). Centimetre-thick sandstone beds with grains made from black Silurian schists and Devonian metaquartzites and metalimestones extensively cropping out in the surrounding area (geological survey from Funedda et al. Reference Funedda, Carmignani, Pertusati, Uras, Pisanu and Murtas2008) are also intercalated. Small synsedimentary normal faults with centimetre-scale displacement are visible (Fig. 6b). Above that, greyish to black, thinly laminated siltstones (Fig. 6e) with rare cross-laminations pass upwards into clayey siltstones. Here linguoid ripples (Fig. 6i) and megaripples are present. The clayey siltstones contain intercalations of decimetre- to centimetre-thick, grey, medium-grained sandstone layers with erosive bases and graded bedding (Fig. 6d). They show flute casts, groove casts and tool casts (Fig. 6h, j). Mud chips have been observed too. Convolute laminations (Fig. 9f) and possible slumping structures are also present in the finer deposits. Upwards, the grain size starts increasing: first are well-bedded, plane-parallel grey sandstones and then follow metre-thick, frequently lens-shaped beds (Fig. 6a) of petromict (Variscan basement pebbles from variable protoliths and quartz) matrix- to clast-supported, medium- to coarse-grained conglomerate beds with waning-waxing structures. The depositional bodies show a high width/thickness ratio (>10) (Table 4). The conglomerate matrix content increases upwards: the coarse deposits are predominant (Table 4). Those conglomeratic beds show non-erosive contacts over the sandstones below (Fig. 6f, g). They form the majority of the top of the unit (Fig. 6a, f, g); they may be locally intercalated by discontinuous finer, dark grey decimetre-thick sandstone to siltstone beds in places with wavy cross-bedding. The greyish to black clayey siltstones also contain plant remains such as branches, stems and leaves, as well as nodules of carbonate-cemented siltstones. Here, rare tiny ostracod shell fragments have been observed. The abundant fossil macro- and microflora content of some fine beds (main taxa: Callipteris, Lebachia (Walchia) piniformis, Cordaites; Florinites Phase miospore assemblage: Pittau et al. Reference Pittau, Del Rio and Funedda2008: for the complete taxa list see Francavilla et al. Reference Francavilla, Cassinis, Cocozza, Gandin, Gasperi, Gelmini, Rau, Tongiorgi and Vai1977 and Pittau et al. Reference Pittau, Del Rio and Funedda2008) allows the assignment of this lower interval to the Late Pennsylvanian (Stephanian). The described stratigraphic unit thins out eastwards until it pinches out completely. The top of the Rio Su Luda Fm is formed by dark grey to greenish petromict (Variscan basement and quartz pebbles) breccias and conglomerates and dark grey-greenish sandstones that are overlain conformably (?) by (and sometimes are mixed with) coarse-grained, reddish conglomerates and minor sandstone and siltstone beds that form the base of the red bed succession of the overlying Mulargia Fm (Costamagna, Reference Costamagna2019). According also to Barca et al. (Reference Barca, Carmignani, Eltrudis and Franceschelli1995), based on different average bedding directions measured during this survey, in the lower (N 140° → SW 30°) and upper (N 170° → S 5°) stratigraphic units, in the Mulargia sector, an unconformity (extending the meaning of the ‘gradational unconformity’ defined by Pettijohn, Reference Pettijohn1975) exists between the Rio Su Luda Fm and the Mulargia Fm. In fact, between the Antoni Cauli and the Taccu Coronas localities (Figs 3, 5, 7), chaotic thick-bedded conglomerates rich in red pebbles and reddish matrix with subordinate intercalations of green-grey conglomerates and thinner green-grey sandstone beds mark the transition between the Rio Su Luda Fm and the Mulargia Fm. A possibly unconformable erosive contact between red conglomerates over dark grey-green well-bedded sandstones is evident in places (Fig. 6k).

Fig. 5. Location and scheme of the measured stratigraphic sections in the NW Mulargia sector of the Mulargia–Escalaplano Basin. The position of the scheme is the red square in Figure 3.

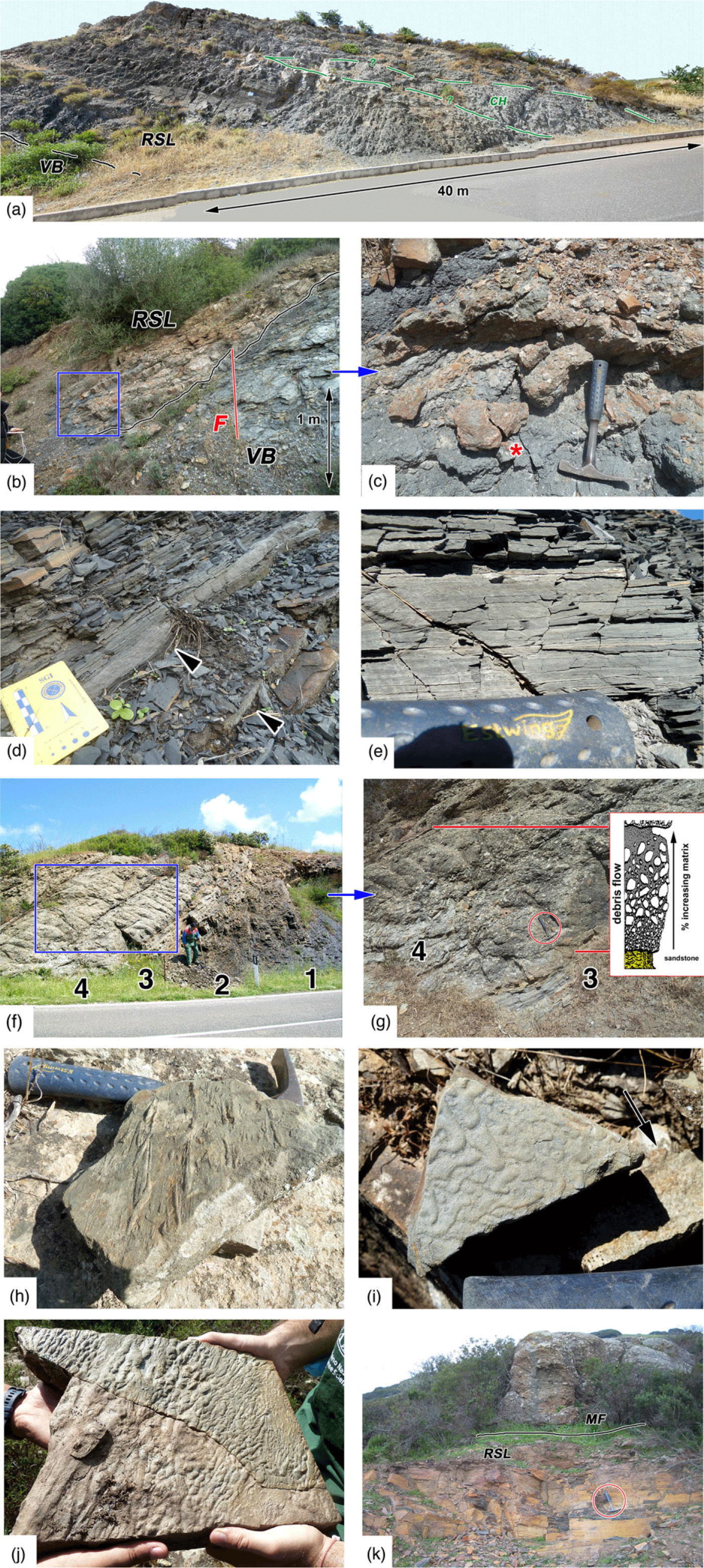

Fig. 6. Lithofacies of the Rio Su Luda Fm in the Mulargia sector. (a) Overview of the lower Rio Su Luda Fm. VB – Variscan basement; RSL – Rio Su Luda Fm; CH – coarse-filled channel. The thickness of the visible RSL section is c. 25 m. Antoni Cauli S road-cut. (b) Rio Su Luda Fm (RSL) basal unconformity on the Variscan basement (VB); F – synsedimentary fault. Blue square: location of the detail in (c). Antoni Cauli. (c) Rio Su Luda basal deposits: quartzose conglomerate–breccias alternated with coarse sandstones deriving from the erosion of the Silurian schists underneath (* – regolith?). Hammer for scale is 30 cm long. Antoni Cauli. (d) Graded sandstone beds with erosive base (arrows) into thinly laminated clayey siltstones. Scale card long side = 8 cm. Rio Su Luda Formation, Antoni Cauli. (e) Thinly laminated siltstones. Hammer handle is 7 cm long. Rio Su Luda Formation, Antoni Cauli. (f) Thinly laminated clayey siltstones (1) followed by siltstones (2), bedded sandstones (3), and poorly bedded, coarse conglomerates (4). Height of man is ∼160 cm. Rio Su Luda Fm succession, Antoni Cauli N road-cut. Blue square: location of the detail in (g). (g) Coarse, coarsening-upward to fining-upward-graded deposits (4) over grey sandstones (3). Inset of modelized features of a subaqueous debris flow event from Nemec & Steel (Reference Nemec, Steel, Koster and Steel1984). Rio Su Luda Fm succession, Antoni Cauli N road-cut. Hammer is 30 cm long. (h) Tool casts and groove casts at the base of a sandstone bed. Hammer for scale is 30 cm long. Rio Su Luda Fm, Genna Ureu. (i) Linguoid ripples on a silty sandstone bed. Hammer handle is 6 cm long. Rio Su Luda Fm, loc. Melas. (j) Flute cast at the base of a sandstone bed. Rio Su Luda Fm, Genna Ureu. (k) Dark grey-green well-bedded sandstones of the Rio Su Luda Fm (RSL) eroded by the chaotic conglomerates–breccias with a reddish matrix of the Mulargia Fm. Hammer is 30 cm long. Antoni Cauli. Stratigraphic location of the pictures in Figure 20.

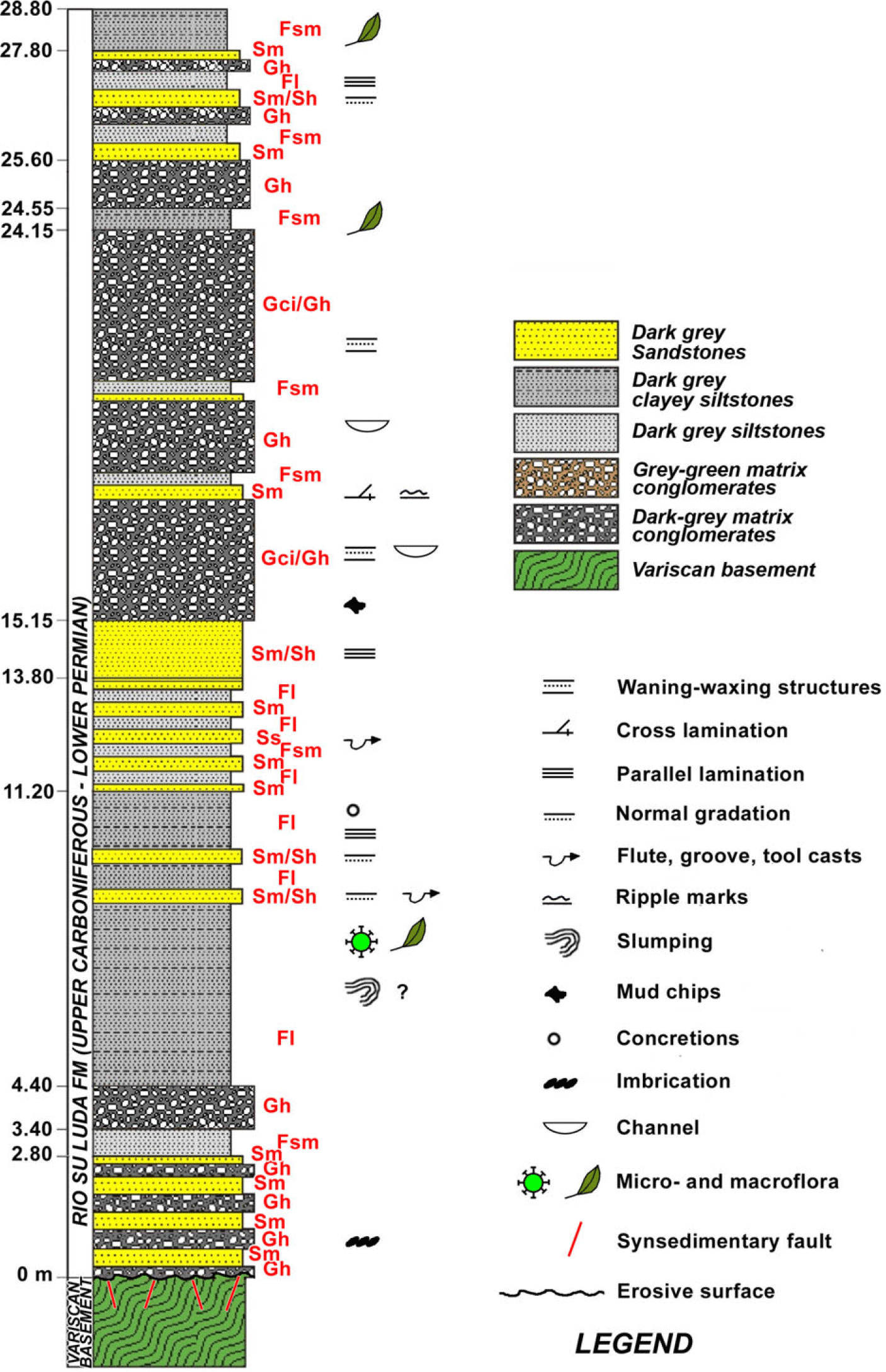

Fig. 7. Stratigraphic column of the Antoni Cauli stratigraphic section. Location in Figures 3 and 5. Facies codes according to Costamagna (Reference Costamagna2018), modified from Miall (Reference Miall, Walker and James1992, Reference Miall1996) and Bridge (Reference Bridge1993).

Fig. 8. Stratigraphic column of the Riu Melas stratigraphic section. Location in Figures 3 and 5. Facies codes according to Costamagna (Reference Costamagna2018), modified from Miall (Reference Miall, Walker and James1992, Reference Miall1996) and Bridge (Reference Bridge1993).

Fig. 9. Micrographs of sandstones in the Carboniferous–Permian succession: (a) Litharenite (Folk, Reference Folk1980) close to the Variscan unconformity, rich in rock fragments from the Silurian schists located immediately underneath. Grains are iso-oriented, graded, imbricated rightwards (blue arrow). The inset shows the detail of typical Silurian schists fragments. NX, Antoni Cauli, Rio Su Luda Fm, Mulargia sector; arrow = 0.5 cm. (b) Fine litharenite (Folk, Reference Folk1980). NX, Mulargia Fm, Terra Segada, Mulargia sector; arrow = 0.5 cm. (c) Arkose (Folk, Reference Folk1980). Grains are iso-oriented. Feldspars (blue arrow), volcanic lithics (red arrows) and metamorphic lithics (green arrow) are evidenced. The inset evidences a feldspar grain. NX, base of the Pegulari Fm, Su Pitzu de Mataracui, Mulargia sector; arrow = 0.5 cm. (d) Carbonate bed sample rich in peloids and iso-oriented, elongated terrigenous lithic grains. A possible plant fragment is evidenced in the inset. Pegulari Fm, Su Pitzu de Mataracui, Mulargia sector; arrow = 0.5 cm; (e) Andesitic lava, top of the succession. NX, Mataracui Andesites Unit, Su Pitzu de Mataracui, Mulargia sector; arrow = 0.5 cm. (e) Erosive surfaces (red arrows) and convolute laminations (green arrow) in a siltstone. N=, Antoni Cauli, Rio Su Luda Fm, Mulargia sector; arrow = 1 cm. (f) Thin convolute laminations in siltstones and clayey siltstones. N=, Trebiali, Mulargia Fm, Escalaplano sector; arrow = 1 cm. (g) Convolute laminations and synsedimentary faults in siltstones and clayey siltstones. N=, Su Pitzu de Mataracui, Mulargia Fm, Escalaplano sector; arrow = 0.5 cm.

Northwards, at the Melas locality (Figs 3, 5, 8), close to the Genna Ureu abandoned Fe–As–Cu mine, a thin, prevalently dark grey ‘limnic’ succession 30 m thick that can still be referred to the Rio Su Luda Fm crops out. Here, Pecorini (Reference Pecorini1974) found a limited macrofloristic assemblage (Lebachia (Walchia) piniformis, Ernestiodendron (Walchia) filiciforme, Callipteris sp.). The ‘limnic’ succession, formed mainly by dark grey sandstones and minor dark siltstones, includes scattered intercalations of conglomeratic to microconglomeratic reddish deposits also containing reworked dark grey centimetre-thick sandstone pebbles.

Conversely, in the East Mulargia sector (Is Xivas: Figs 3, 10), over the Variscan basement outcrops are lens-shaped chaotic petromict conglomerates in a greenish matrix with minor greenish sandstone beds; they are embedded in reddish siltstones and clayey siltstones. This diverse basal lithofacies may represent the local base of the following Mulargia Fm or, given their unusual characters (colour, grain size, texture, feeding), a peculiar, transitional thin remnant of the Rio Su Luda Fm (Fig. 11d). Sedimentary structure measurements point to a southeastward transport direction of the sediment (Figs 3, 27; Table 5).

Fig. 10. Stratigraphic column of the Is Xivas stratigraphic section. Location in Figure 3. Facies codes according to Costamagna (Reference Costamagna2018), modified from Miall (Reference Miall, Walker and James1992, Reference Miall1996) and Bridge (Reference Bridge1993).

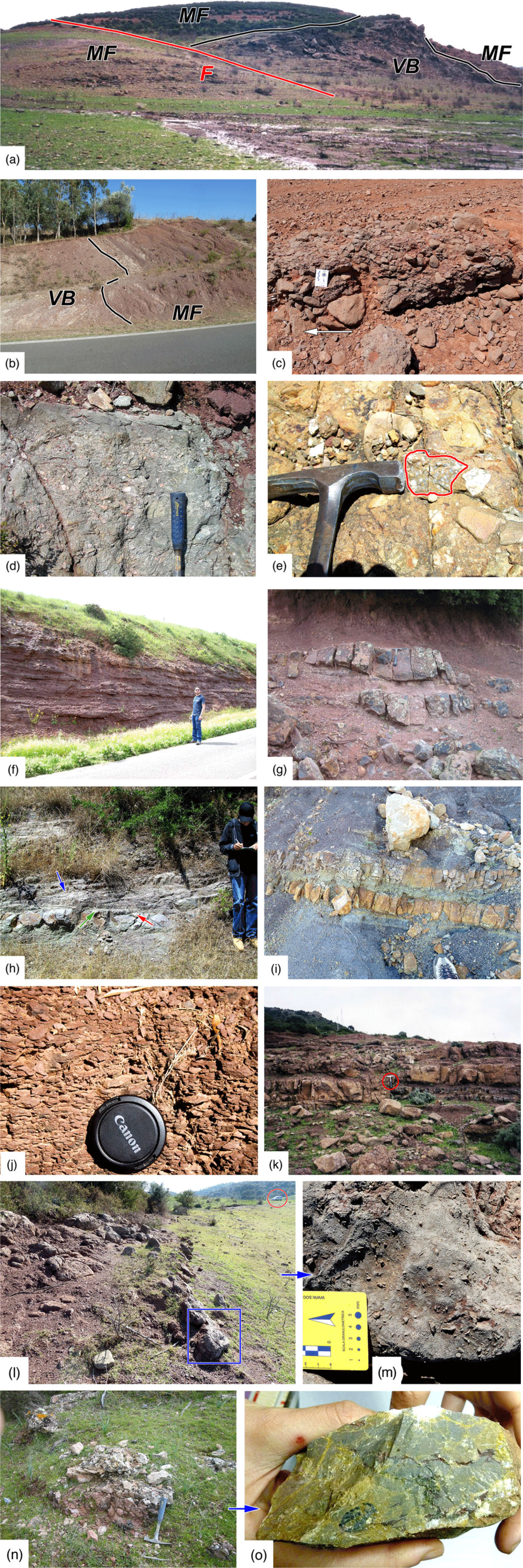

Fig. 11. Lithofacies of the Mulargia Fm and the Sa Fossada Rhyolites Unit of the Upper Rotliegend Group. (a) Irregular basal unconformity of the Mulargia Fm (MF) over the Variscan basement (VB). F – fault. The hill is 20 m high. Loc. Terra Segada (Mulargia sector). (b) Inclined basal unconformity of the Mulargia Fm over the Variscan basement (VB). Field width 20 m. Cuccuratu (Escalaplano sector). (c) Poorly bedded, polymict, imbricated conglomerates. The arrow shows the flow direction. Mulargia Fm, Terra Segada (Mulargia W sector); scale measurer long side = 8 cm. (d) Chaotic petromict conglomerates in a greenish matrix with minor greenish sandstone beds. Hammer handle is 20 cm long. Upper Rio Su Luda Fm or lower Mulargia Fm? Is Xivas (Mulargia sector). (e) Pebble of quartzose conglomerate embedded at the base of the Mulargia Fm. Hammer is 15 cm long. Is Xivas (Mulargia sector). (f) Irregular beds of clast- to matrix-supported unchannelized conglomerates and breccias intercalated by reddish siltstones in the Mulargia Fm. Antoni Cauli (Mulargia sector). Height of man is 170 cm. (g) Lens-shaped sandstone bodies with erosive base in the Mulargia Fm. Hammer is 30 cm long. Is Xivas (Mulargia sector). (h) Lateral accretion structures (blue arrow) with a thin basal lag (green arrow) over an erosional surface (red arrow) in the Mulargia Fm. Height of man is 170 cm. Su Pitzu de Mataracui (Mulargia sector). (i) Beds of silicified carbonates in the Mulargia Fm. Shoe length is 15 cm. Cuccuratu (Escalaplano sector). (j) Reddish siltstones/clayey siltstones (camera objective cover size is 5 cm) in the Mulargia Fm. Su Pitzu de Mataracui (Mulargia sector). (k) Alternations of ignimbrites and reddish siltstones/clayey siltstones in the Sa Fossada Rhyolitic Unit. Mulargia Fm. Hammer is 30 cm long. Corte Caboni (Mulargia sector). (l) Right-dipping carbonate beds close to the base of the Mulargia Fm. Car in the background for scale. Monte Maiori (Mulargia sector). (m) Detail showing the abundance of schist angular pebbles in the carbonates. Monte Maiori (Mulargia sector). (n) Isolated, lens-shaped silicified carbonate bed in the red beds of the Mulargia Fm. Taccu Coronas (Mulargia sector). (o) Sample of silicified calcilutite with thin red pelite laminae and a Gastropoda fossil fragment collected from the former outcrop in the Mulargia Fm. Taccu Coronas (Mulargia sector). Stratigraphic location of the pictures in Figure 20.

In other parts of the Mulargia sector, even those separated from the main outcrops as at Bruncu Su Para and Fruscanali (Fig. 3), and eastwards, in the Escalaplano sector, the Rio Su Luda Fm is missing and the overlying Mulargia Fm red bed succession of the Upper Rotliegend Group lies unconformably over the Variscan basement.

Observations in thin-section show the analogies between the Silurian rock in place and the fragments contained in the sandstones (Fig. 9a). The modal analysis of a representative sandstone samples collected along the Antoni Cauli stratigraphic section gave the values Qt61 F4 L35 (Qz39 F4 Lt57). Petrographic average modal analysis of some samples (Costamagna et al. in progress) shows that the sandstones of the Rio Su Luda Fm are basement-fed litharenites with less than 60 % quartz (Folk, Reference Folk1980). Lithic grains derived mainly from the Silurian black schists of the Variscan basement (Fig. 9).

4.a.2. Upper Rotliegend Group: Mulargia Fm, Sa Fossada Rhyolites Unit, Pegulari Fm, Mataracui Andesites Unit

4.a.2.a. Mulargia sector

In the Mulargia sector, the Upper Rotliegend Group red bed succession, usually having a horizontal to sub-horizontal attitude, can be subdivided from bottom to top into four stratigraphic units (Figs 10, 12–14):

(1) A reddish lower siliciclastic unit, showing a variable thickness of between 150 m (Western Mulargia sector) and 100 m (Eastern Mulargia sector), and henceforth named the Mulargia Fm. In the southern part of the West Mulargia sector and in the East Mulargia sector the transgressive surface over the Variscan basement is rough, showing low swells and shallow scours locally separated by normal faults with metre-scale displacement (Fig. 11a); the scours are filled by coarser deposits. The Mulargia Fm starts with alternations of chaotic to weakly organized, petromict conglomerates (Variscan basement, quartz, rare undeformed quartzrudite and quartzarenite (Fig. 11e) and volcanic pebbles from the previous late-orogenic cycles: Rio Su Luda Fm?) and reddish matrix-supported breccias (fanglomerates) (Fig. 11f). They form lens-shaped depositional bodies with a high width/thickness ratio (>10, sometimes even more) decreasing eastwards (Fig. 11f; Table 4). Locally, close to the western border of the southwestern Mulargia sector (Monte Maiori), 1 to 2 m of dark grey carbonate beds rich in millimetre- to centimetre-sized schist and quartz fragments lie directly over the petromict basal conglomerate that here is no more than 1.5 m thick (Fig. 11l, m) and rests unconformably over the Variscan basement. Limited, not more than 25 cm thick, intercalations of terrigenous coarse deposits grey-green in colour are still locally present. The bed geometry changes upwards and eastwards as well: they pass gradually eastwards from tabular-shaped to lens-shaped (westward Mulargia → eastward Mulargia → Escalaplano sectors: 1, 2, 3 in Fig. 2; Table 4). Upwards, alternations of reddish sandstones, siltstones and clayey siltstones with minor conglomerates follow: here the conglomerate + sandstone/siltstone + clayey siltstone ratio decreases towards the top as well as eastwards (Table 4). The sandstone beds are usually lens-shaped; they show several scale orders, and a nested hierarchy with local lateral accretion surfaces (Fig. 11h). There are also thinner reddish, sheet-like to lenticular graded, sandstone beds (Fig. 11g). All of these are embedded in reddish siltstones and clayey siltstones (Fig. 11j) locally showing mud cracks. Imbrication measurements point to a southeastward transport direction of debris (Figs 3, 27; Table 5). Levels with irregularly distributed nodular (pedogenic?) calcretes as well as scattered and rare, laterally discontinuous decimetre-thick yellowish silicified carbonate, rarely marly, lensoid to tabular-shaped beds are locally intercalated in the lower part of that lithofacies, particularly close to its base (Fig. 11i, n, o). Towards the top, the increase in volcanic and volcaniclastic beds with siliciclastic deposits indicates the gradual passage into the volcano-sedimentary unit (Fig. 11k).

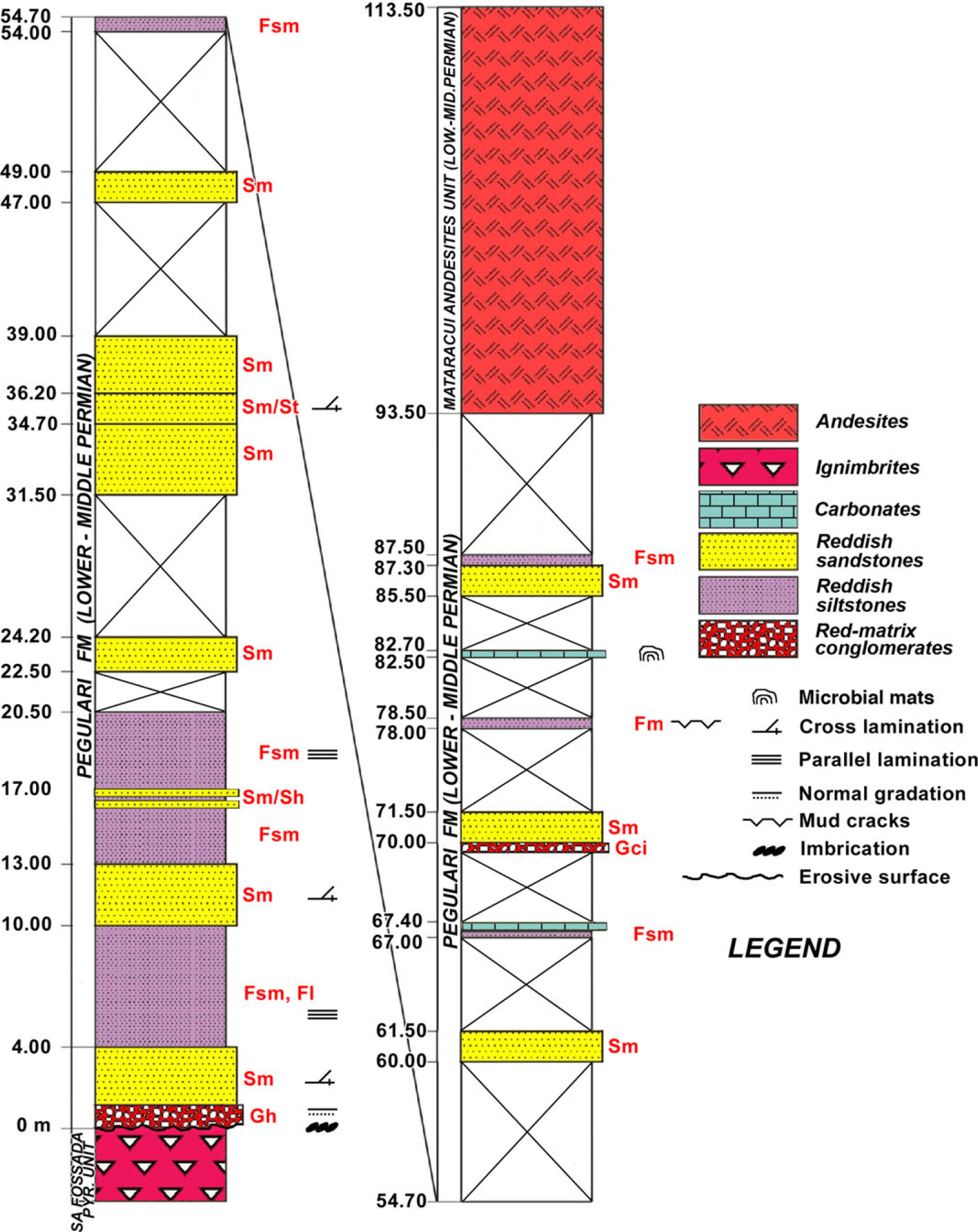

Fig. 12. Stratigraphic column of the Taccu Coronas stratigraphic section. Location in Figures 3 and 5. Facies codes according to Costamagna (Reference Costamagna2018), modified from Miall (Reference Miall, Walker and James1992, Reference Miall1996) and Bridge (Reference Bridge1993).

Fig. 13. Stratigraphic column of the Pitzu de Mataracui stratigraphic section. Location in Figure 3. Facies codes according to Costamagna (Reference Costamagna2018), modified from Miall (Reference Miall, Walker and James1992, Reference Miall1996) and Bridge (Reference Bridge1993).

Fig. 14. Stratigraphic column of the Corte Caboni stratigraphic section. Location in Figure 3. Facies codes according to Costamagna (Reference Costamagna2018), modified from Miall (Reference Miall, Walker and James1992, Reference Miall1996) and Bridge (Reference Bridge1993).

The framework modal analysis of a representative sandstone sample collected in the Terra Segada locality (western Mulargia sector) from the Mulargia Fm (Costamagna et al. in progress) gave the values Qt55 F8 L37 (Q50 F8 Lt42) (Fig. 9b), and it shows they are litharenites, slightly more mature than the Rio Su Luda ones.

(2) The upper volcano-sedimentary unit has been named the Sa Fossada Rhyolites Unit (Funedda et al. Reference Funedda, Carmignani, Pertusati, Uras, Pisanu and Murtas2008) and is ∼50 m thick. It is built of pyroclastic rocks (mainly rhyolitic ignimbrites; Assorgia et al. Reference Assorgia, Maccioni and Macciotta1983) locally with flame structures and forming depositional couplets with thin, millimetre- to centimetre-thick irregular volcaniclastic sandstone–siltstone beds. Red, decimetre-thick clayey siltstone beds are locally intercalated.

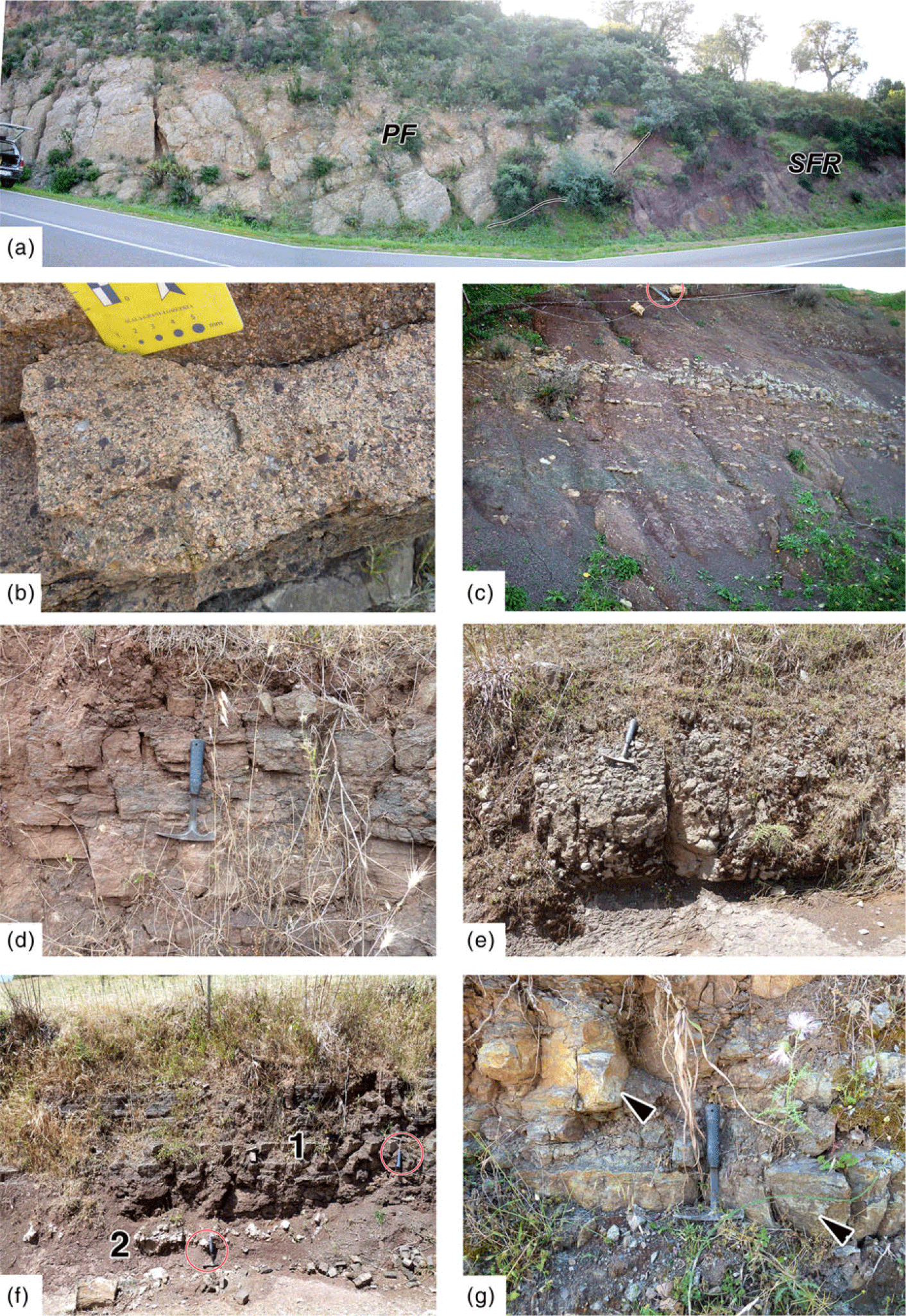

(3) Unconformably follows a red bed siliciclastic unit henceforth named the Pegulari Fm (Figs 3, 13, 14), which is formed by an 80 m thick fining-upward succession starting with a horizon of reddish to greenish petromict conglomerates and breccias (Variscan basement, quartz and Permian volcanics, red bed and ‘limnic’ succession pebbles) locally showing imbrications (Tables 3, 4). The thickness of this basal horizon varies between 1.5 and 8 m. It passes rapidly into medium- to coarse-grained, cross-bedded and lens-shaped feldspar-rich sandstone beds (Fig. 15b) with lateral accretion surfaces interbedded with thin beds of reddish-violet, rarely greenish siltstones. Upwards follow reddish siltstones – clayey siltstones; here sandstone beds and very rare thin beds of chaotic petromict conglomerates usually with tabular shapes may occur. The source of the pebbles in the coarser lithologies is from the eroded Sa Fossada Rhyolites Unit, the Mulargia Fm, the Rio Su Luda Fm and, subordinately, quartz and metamorphic rocks from the Variscan basement. Cross-bedding in the sandstones suggests a flow directed towards the SE (Tables 3, 4). In the middle part of this unit, scattered decimetre-thick discontinuous tabular to nodular beds of yellowish to dark grey silicified limestone to dolomitic limestone with rare marls are intercalated in reddish siltstones – clayey siltstones embedding quartz nodules (former evaporites). The carbonates consist of algal-fenestral bindstones with tiny crystals of former evaporites (now calcite) alternating with clotted calcilutites (micrites) and fine calcarenites. The carbonates and the associated reddish to greenish mudstones are commonly silicified.

Fig. 15. Lithofacies of the Pegulari Fm of the Upper Rotliegend Group. (a) Unconformity of the basal conglomerates of the Pegulari Fm (PF) over the siltstones/clayey siltstones and pyroclastic rocks of the Sa Fossada Rhyolites Unit (SFR). Pegulari (Escalaplano sector). The trunk of the car on the far left for scale is 150 cm. (b) Arkoses of the Pegulari Fm. Scale card short side = 5 cm. Loc. Su Pitzu de Mataracui (Mulargia sector). (c) Silicified carbonate decimetre-thick beds in siltstones/clayey siltstones in the Pegulari Fm. Hammer is 30 cm long. Pegulari (Escalaplano sector). (d) Well-bedded sandstones in the Pegulari Fm. Hammer is 30 cm long. Genn’E Gracca (Escalaplano sector). (e) Petromict conglomerates (Permian volcanic rocks and Variscan basement) at the base of the Pegulari Fm. Hammer is 30 cm long. Genn’E Gracca (Escalaplano sector). (f) Alternations of sandstones, siltstones/clayey siltstones (1), and minor silicified carbonates (2) in the Pegulari Fm. Hammers are 30 cm long. Genn’E Gracca (Escalaplano sector). (g) Silicified cinerites and carbonates in the Pegulari Fm. Hammer is 30 cm long. Pranu e’ S’Artu (Escalaplano sector). Stratigraphic location of the pictures in Figure 3.

The framework modal analysis of a representative sandstone sample collected in the Punta de Mataracui locality (Costamagna et al. in progress) gave the values Qt28 F32 L50 (Q12 F32 Lt56) (Fig. 9c): it shows they are volcaniclastic litharenites whose source probably came mainly from the dismantling of the lower Permian volcanic rocks. The carbonates may also be rich in terrigenous grains: quartz and metamorphic lithics are represented (Fig. 9d).

(4) At the top of the succession, an andesitic volcanic unit henceforth named the Mataracui Andesites Unit (Funedda et al. Reference Funedda, Carmignani, Pertusati, Uras, Pisanu and Murtas2008), ∼20 m in thickness, occurs. It is formed by dark effusive andesites showing plagioclase crystals and rare amphiboles in a dark groundmass rich in smaller feldspar, femic crystals and glass (Assorgia et al. Reference Assorgia, Maccioni and Macciotta1983) (Fig. 9e).

On the whole, the Upper Rotliegend Group in the Mulargia sector reaches a maximum thickness of 250 to 300 m.

4.a.2.b. Escalaplano sector

In the easternmost Escalaplano sector (Figs 2, 4) the basin succession commences with the red bed Mulargia Fm. The stratigraphy of the red beds of the Upper Rotliegend Group is similar to that in the Mulargia sector and can be subdivided in the same way (Figs 4, 16). Nonetheless, significant differences exist laterally between the same formational units. There are differences in (a) the relative abundance of lithologies; (b) thickness, conglomerate + sandstone/siltstone + clayey siltstone ratio; (c) structures (Table 5); (d) composition of the conglomerate pebbles and sandstone grains; and (e) sedimentology numerical parameters (Table 4).

(1) The Mulargia Fm is here not more than 70 m thick and it is on average much finer in grain size than its western counterpart. The basal red bed polymict conglomerate, here forming a single (amalgamated?) coarse body (and evidenced as such in Fig. 4), rests over the Variscan basement through a metre-thick regolith and contains frequently SE-imbricated undeformed grey-green sandstones, brown-reddish volcanic pebbles and porphyrites pebbles (Fig. 27; Table 5). Volcaniclastic sandstones and tuffites (?) are frequent along all the unit. The bed architecture (sensu Miall, Reference Miall1996) of the coarse-grained deposits is simpler, and the lens-shaped beds are smaller and thinner (Table 4). Dark grey to greenish, decimetre-thick thinly laminated siltstones and clayey siltstone intercalations can be present in the lower part of the unit; Pecorini (Reference Pecorini1974) found here a macrofloristic assemblage (Lebachia (Walchia) piniformis, Ernestiodendron (Walchia) filiciforme, Callipteris sp.: Late Pennsylvanian, Pittau et al. Reference Pittau, Del Rio and Funedda2008). Calcretes and decimetre-thick carbonate beds are frequent (ostracods, Characeae oogons, gastropods, plant fragments? Pecorini, Reference Pecorini1974; Costamagna, Reference Costamagna2019).

(2) The Sa Fossada Rhyolites Unit is thinner, more massive in appearance and made up of pyroclastic rocks and ignimbrites. Moreover, the Sa Fossada Rhyolites Unit here usually misses the reddish sandstone–siltstone regular intercalations between different magmatic events but shows a significant volume of volcaniclastic sandstones and hyaloclastites.

(3) Also, in the Pegulari Fm the siliciclastic deposits on average show a finer grain size and a more marked volcaniclastic origin. Thickness is about the same, as it is 80 m. The transition from the Sa Fossada Rhyolites Unit to the Pegulari Fm is less well defined here: volcanic deposits, although strictly subordinated, persist above the basal conglomerate level (Fig. 15a). This latter is coarser than the corresponding level in the Mulargia sector, and it is formed by roughly bedded petromict conglomeratic breccias (volcanic rocks, quartz and rare metamorphic Variscan rocks) and conglomerates whose thickness is irregularly variable from 12 to 1.5 m. SE-oriented imbrication has been observed (Figs 15e, 27; Table 5). This basal level may rest over reddish siltstones and clayey siltstones (Pegulari, Fig. 15a) or over coarse pyroclastic rocks. The scarce conglomerates here present are texturally and compositionally more mature than those in the Mulargia sector. Above the basal conglomerates of the Pegulari Fm occurs a thick pyroclastic bed (a lahar, according to Ronchi in Cassinis et al. Reference Cassinis, Cortesogno, Gaggero, Pittau, Ronchi and Sarria2000). The lower feldspathic sandstones close to the base of the Pegulari Fm and cropping out in the Mulargia sector are not present here. Carbonate beds are present (Figs 15c, f, 17). Besides the basal level, the conglomerate beds are thin and very rare, and the tabular to lens-shaped sandstone beds (Fig. 15d, f) are smaller and thinner than those of the Mulargia Fm (Table 4). Silicified volcanic deposits (Fig. 15g) are rare.

(4) The upper passage from the Pegulari Fm to the Mataracui Andesites Unit is sharp. The Mataracui Andesites Unit here is significantly thicker, reaching at least 50 m.

Significantly, in the Escalaplano sector, the carbonate intercalations are more diffuse and thick, especially in the upper Pegulari Fm. At Pegulari (Fig. 4) a short stratigraphic section along a road-cut has been investigated in detail. The studied section (Fig. 17) occurs ∼20–25 m above the conglomeratic base of the Pegulari Fm. It consists of 8 m of irregular alternation of massive to locally laminated reddish siltstones to clayey siltstones/mudstones and laminated greyish-green siltstones to clayey siltstones/mudstones, containing several centimetre- to decimetre-thick light dark grey to yellowish carbonate to carbonate-marly beds in the middle. The carbonate beds are recrystallized, frequently silicified limestones and dolomitic limestones with scarce terrigenous content and sparse bioturbation. The carbonates are preferentially associated with the greyish-green clayey siltstones/mudstones, and locally show mottling and scattered ghosts of millimetre-sized, rounded aggregates (oncolites? bioclasts?). The beds are continuous to nodular in shape, showing a cyclic recurrence. The carbonate microfacies (Fig. 18) shows planar to wavy microbial lamination with elongated cavities (laminoid fenestrae, fenestral bindstones; Demicco & Hardie, Reference Demicco and Hardie1994) and localized packstones with a pelletoidal structure (Flügel, Reference Flügel2004). It alternates with recrystallized (pedogenized?) clotted to structureless carbonate, mudstones to wackestones with ghosts of rounded aggregates (bioclasts?), and thin shell fragments (ostracods, gastropods). Cavities filled with carbonate and locally replaced by late diagenetic quartz are also present (Fig. 18b). Frequent post-depositional features such as pseudobreccias, intragranular shrinkage fractures, spar-filled microcracks and circum-granular cracks occur (Fig. 18c).

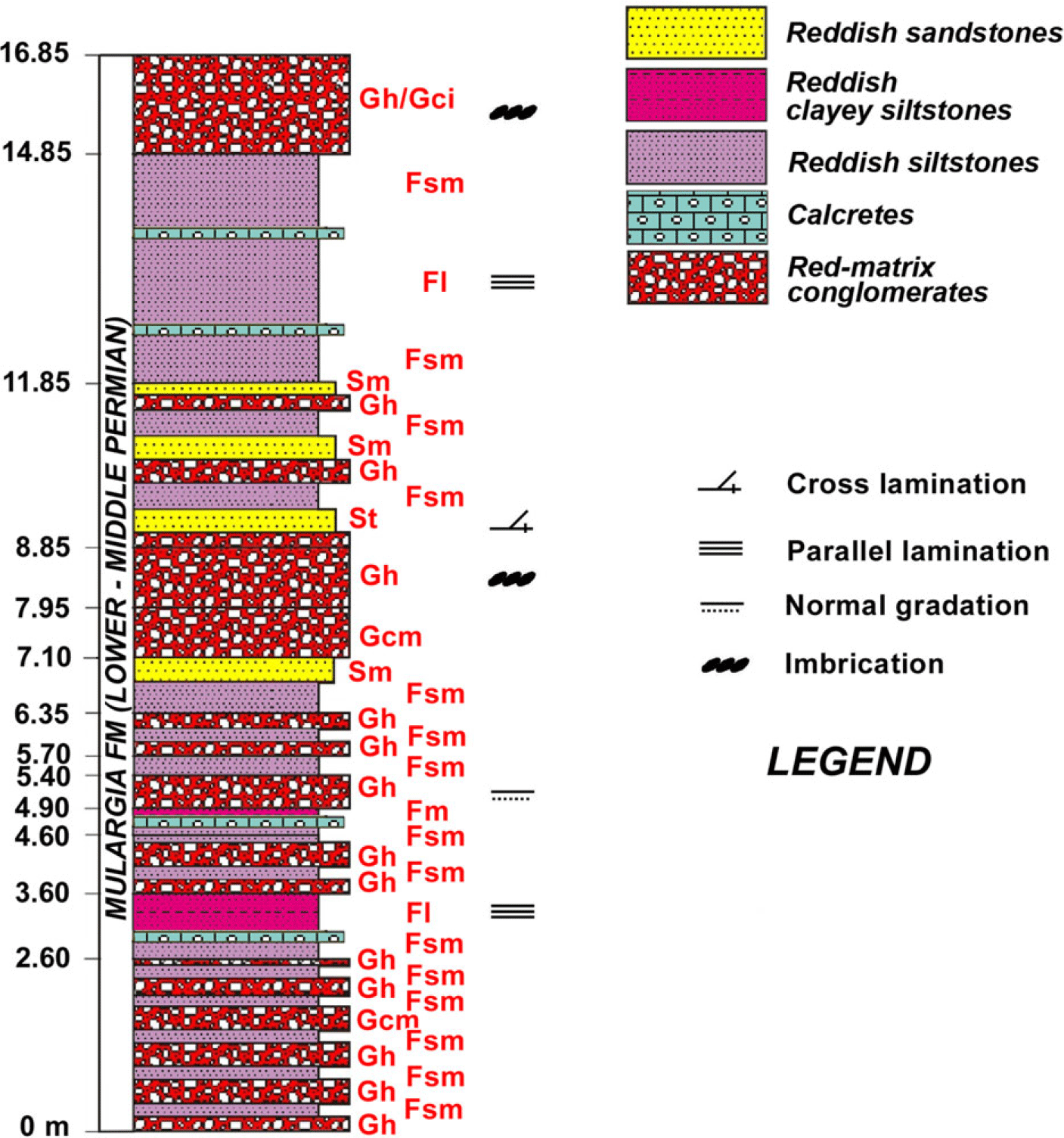

Fig. 16. Main stratigraphic columns and lithocorrelations of the SE Escalaplano sector of the Mulargia–Escalaplano basin. Modified from Cassinis et al. Reference Cassinis, Cortesogno, Gaggero, Pittau, Ronchi and Sarria2000. Facies codes according to Costamagna (Reference Costamagna2018), modified from Miall (Reference Miall, Walker and James1992, Reference Miall1996) and Bridge (Reference Bridge1993). In the carbonate-bearing lithofacies, the facies code refers to the siliciclastic portion.

Fig. 18. Micrographs of the carbonate facies of the Pegulari Fm. (a) Wavy fenestral microbialite (black arrow) passing upwards to a packstone with pelletoidal texture (red arrow). (b) Clotted, weakly pedogenized packstone with glaebules (black arrow) and desiccation vugs (red arrow) filled by one or two generations of calcite cement. (c) Pedogenized micrite with glaebules (black arrow), shrinkage (red arrow) and circum-granular (blue arrow) cracks. The wide quartz-filled large fractures (green arrow) are possible desiccation structures (up to the right: black arrow). (d) Microbialitic mats with an interposed evaporite bed (green arrow). (e) Microbialitic mats with silicified, former evaporite crystals (green arrow). Scale bars = 1 cm. N=. Stratigraphic location in Figure 20.

A dislodged, loose block (16 × 14 × 8 cm in size; Fig. 19a–d) of silicified carbonates and clayey siltstones/mudstones with characteristic sedimentological features was collected from the Pegulari stratigraphic section of the Pegulari Fm and studied in detail. It is formed by a centimetre-sized alternation of reddish to dark grey massive, structureless clayey siltstones/mudstones with some carbonate and organic matter content, and delicately laminated grey microbial lamination (Fig. 19b). Between the microbial laminae occur sub-millimetre scale, sub-rectangular crystal pseudomorphs of sulphate(?) and tiny, lined-up elongate cavities. Also, centimetre-sized soft muddy intraclasts are interbedded (Fig. 19c). The mat-like laminae are delicately draped over irregular, fractured surfaces developed over the mudstones (Fig. 19b), and in turn, are covered by mudstone. The boundary between the mudstones and the microbialite is marked by load casts. Post-depositional deformation is also common. The mudstones have millimetre-sized, rounded to irregular vugs filled with one or two generations of former calcite cement, or by quartz (Fig. 18d). Centimetre-sized aligned quartz displacive elongated nodules are embedded in the mud.

Fig. 19. Features of the carbonate deposits of the Pegulari Fm. Dislodged block with centimetre-thick alternation of silicified carbonate and siliciclastic mudstone in (a) overview and (b–d) details. (a) Microbial mats (white arrows) and former evaporitic nodules (now quartz, red arrows). Loc. Pegulari (Escalaplano sector). (b) Laminated microbial mats with rectangular former evaporitic crystals (white arrow) and load casts (red arrow). (c) Soft muddy intraclasts in the microbial mats (white arrow). (d) Quartz-filled vugs in the microbial mats (white arrow) and in the mudstone (red arrow). Coin size = 2 cm. (e) Dislodged block of algal bindstone showing domal structures with intergrowth of evaporitic crystals (black arrow) now pseudomorphed by quartz. Loc. Su Pitzu de Mataracui (Mulargia sector). (f) Dislodged block of massive fenestral microbialitic mats with planar and domal structures. In the middle are convolute structures of unknown origin (hydroplastic movements? bioturbation?) in micrite (interval marked by a curly bracket). Coin size = 2 cm. Loc. Pran’e Sartu (Escalaplano sector). Some details in (g, h). (g) Alternations of microbial mats and thin micritic laminae: quartz evaporitic pseudomorphs (e.g. black arrow) are located in between. Coin size = 2 cm. (h) Alternations of micritic beds with quartz evaporitic pseudomorphs (black arrows) and pelletoidal-bioclastic graded beds with gently erosive base (red arrows). Scale in millimetres. Stratigraphic location in Figures 4, 16 and 20.

Other loose carbonate blocks (25 × 21 × 18 cm in size; Fig. 19e; 31 × 12 × 10 cm in size; Fig. 19f–h) have been found and collected close to discontinuous well-bedded carbonate outcrops of the Pegulari Fm of the Mulargia sector (Su Pitzu de Mataracui, Fig. 3) and the Escalaplano sector (Planu e’ S’Artu, Fig. 4). They are lithologically more homogeneous than the formerly described Pegulari block: they are formed entirely by alternations of laterally continuous microbial laminae from planar to wavy to dome-shaped (Fig. 19f, g), separated by tiny, lined-up elongate cavities (Fig. 19g), micritic beds and bioclastic-pelletoidal, frequently graded beds with erosive bases (Fig. 19h). Structures interpretable as being due to hydroplastic movements or perhaps possible traces of bioturbation can be present (Fig. 19f). Small amounts of millimetre-sized cubic to prismatic quartz crystals are scattered: they are located in between the microbial laminae (Fig. 19g) and in the micrite beds (Fig. 19h).

The entire Upper Rotliegend Group of the Escalaplano sector is thinner than in the Mulargia sector, measuring only 150 to 200 m, possibly due to a higher erosion rate (Pecorini, Reference Pecorini1974). The volcanic intercalations in the Escalaplano sector were chronologically dated (Figs 20–22). Based on laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry U–Pb zircon dating, the Sa Fossada Rhyolites Unit is 302 ± 2.9 Ma old (Stephanian or Kasimovian/Gzhelian), while the Mataracui Andesites Unit gave an age of 295 ± 2.9 Ma (‘Autunian’ or Asselian to Sakmarian?) (Gaggero et al. Reference Gaggero, Gretter, Langone and Ronchi2017).

Fig. 20. A 2D model of the Mulargia–Escalaplano basin showing the NW–SE stratigraphic evolution. Note the several unconformities, and, in the eastward direction (a) the decrease in thickness and mean grain size of the stratigraphic units; (b) the rapid thinning up to the disappearance of the Rio Su Luda Fm; (c) the growing presence of carbonate rocks. A – alluvial environment; L – lacustrine–palustrine? environment; V – volcanic rocks. Radiometric data after Gaggero et al. (Reference Gaggero, Gretter, Langone and Ronchi2017).

Fig. 21. Comparison among magmatic age and affinities, stratigraphy and sedimentation in Sardinia, Provence, the Lodève basin, Autun basin, Saar-Nahe basin and Catalan Pyrenees. In black writing are the volcanic rocks embedded in the ‘limnic’ successions; in red writing are the volcanic rocks embedded in the red bed successions. In violet writing are the volcanic rocks embedded in the transitional successions. Based on: Zheng et al. (Reference Zheng, Mermet, Toutin-Morin, Hanes, Gondolo, Morin and Féraud1992), Lopez et al. (Reference Lopez, Gand, Garric, Körner and Schneider2008), Schäfer (Reference Schäfer2011), Gretter et al. (Reference Gretter, Ronchi, López-Gómez, Arche, De la Horra, Barrenechea and Lago2015), Gaggero et al. (Reference Gaggero, Gretter, Langone and Ronchi2017), Pellenard et al. (Reference Pellenard, Gand, Schmitz, Galtier, Broutin and Stéyer2017) and Schneider et al. (Reference Schneider, Lucas, Scholze, Voigt, Marchetti, Klein, Oplustil, Werneburgh, Golubev, Barrick, Nemyrovska, Ronchi, Day, Silantiev, Rößler, Saber, Linnemann, Zharinova and Shen2020). The time frame has been provided by the Permian Time Scale 2012 of the International Commission of Stratigraphy (Shen et al. Reference Shen, Henderson, Rocha, Pais, Kullberg and Finney2014).

Fig. 22. Tentative correlation between late- to post-Variscan and ‘Alpine’ upper Carboniferous, Permian and Lower–Middle Triassic main stratigraphic units of Sardinia. Volcanic rock radiometric ages, serial magmatic affinities, facies characters, biostratigraphic data and unconformities have been used. Data from: Cassinis et al. (Reference Cassinis, Cortesogno, Gaggero, Ronchi and Valloni1996, Reference Cassinis, Cortesogno, Gaggero, Pittau, Ronchi and Sarria2000, Reference Cassinis, Cortesogno, Gaggero, Ronchi, Sarria, Serri and Calzia2003), Pittau et al. (Reference Pittau, Barca, Cocherie, Del Rio, Fanning and Rossi2002, Reference Pittau, Del Rio and Funedda2008), Deroin & Bonin (Reference Deroin and Bonin2003), Barca & Costamagna (Reference Barca and Costamagna2005, Reference Barca and Costamagna2006 b), Buzzi et al. (Reference Buzzi, Gaggero and Oggiano2008), Ronchi et al. (Reference Ronchi, Sarria and Broutin2008), Gaggero et al. (Reference Gaggero, Gretter, Langone and Ronchi2017) and Costamagna (Reference Costamagna2019). Thicknesses of the successions are merely indicative.

The petrographic analysis of some representative sandstone samples from the red bed succession shows that they are generally basement- to volcanic-fed litharenites, with rare feldspathic litharenites (Folk, Reference Folk1980). The lens-observation shows a transition from basement-fed to volcanic-fed sandstones upwards and southeastwards in the basin along and sideways in the Upper Rotliegend Group succession. The presence of feldspar grains matches that of the volcanic grains. In the lower sandy beds of the Mulargia Fm are rare sandstone grains rich in dark, elongated Variscan basement fragments; these grains are very similar in appearance to the litharenites of the Rio Su Luda Fm.

In the Mulargia–Escalaplano area, the late- to post-Variscan succession is covered unconformably by the lower Eocene Monte Cardiga Fm (Pertusati et al. Reference Pertusati, Sarria, Cherchi, Carmignani, Barca, Benedetti, Chighine, Cincotti, Oggiano, Ulzega, Orru and Pintus2002), or, more rarely, by the Middle Triassic Escalaplano Fm (Costamagna et al. Reference Costamagna, Barca, Del Rio and Pittau2000; Costamagna & Barca, Reference Costamagna and Barca2002) of the Buntsandstein facies, or by Cenozoic to Quaternary volcanic rocks (Assorgia et al. Reference Assorgia, Maccioni and Macciotta1983).

4.b. Interpretation and discussion of the tectonosedimentary context

4.b.1. Lower Rotliegend Group: depositional environment

Collected sedimentological data (synthesis in Figs 20, 23, 27; Tables 4, 5) show that the Rio Su Luda Fm of the Lower Rotliegend Group was deposited in a terrigenous, alluvial to shallow-to-profundal lacustrine–palustrine environment. The latter was episodically affected by high-energy events. Given the limited thickness of the coarse deposits in the lower stratigraphic record, no evidence of significant alluvial fans (fan deltas? cf. Nemec & Steel, Reference Nemec, Steel, Nemec and Steel1988; Reading & Collinson, Reference Reading, Collinson and Reading1996) connecting the Variscan reliefs and the alluvial plain was found; perhaps the basin was originally wider, and the fan evidence was eroded before the Upper Rotliegend Group sedimentation cycle. This assumption could be hinted at by the subaqueous high-energy coarse conglomerate deposits in the middle to upper part of the formation; that coarse debris could represent a distal deposit and must have had a source from somewhere located in a higher place and westward behind the present outcrops: a presently eroded alluvial fan. This seems to be supported by the feeding composition of local provenance. Alternatively, environmental connections between erosive areas and high- to low-energy deposition areas at the start of the basin were simply represented by a few coarse alluvial lobes and splays, suggesting reduced altitude gaps between highs and lows (cf. Collinson, Reference Collinson and Reading1996) and an already smoothed landscape. In the Rio Su Luda Fm, close to the base of the succession, thin sandstone beds rich in disintegrated fine angular Silurian schist fragments in between coarser deposits (Fig. 6c) could be interpreted as regolith, or debris from Silurian schists fragmented by a close synsedimentary fault. An initial gradual decrease of the depositional energy can be deduced from the progressive fining-upward lithological evolution. This, together with abundant plant debris in the lower energy deposits, points to an alluvial to lacustrine–palustrine? anoxic deposition in a gradually deepening environment from alluvial lobes through a lakeshore to profundal lake zone rich in fine laminated deposits (Costamagna, Reference Costamagna2019) (cf. Collinson, Reference Collinson and Reading1996; Talbot & Allen, Reference Talbot, Allen and Reading1996; Lopez et al. Reference Lopez, Gand, Garric, Körner and Schneider2008). Cross-bedding in the siltstones, as well as linguoid ripples, suggest localized low-velocity currents (cf. Collinson et al. Reference Collinson, Mountney and Thompson2006) in the lake shoreface. In the lake bottom the sedimentation, mainly consisting of clayey siltstones from suspension settling, was episodically interrupted by sandy graded events interpretable through flute, groove and tool casts at their base as lacustrine turbidites (cf. Sturm & Matter, Reference Sturm, Matter, Tucker and Matter1978; Reineck & Singh, Reference Reineck and Singh1980; Talbot & Allen, Reference Talbot, Allen and Reading1996). This, together with slumping and convolute laminations, hint at possibly coeval seismic shocks (cf. Rodríguez-Pascua et al. Reference Rodríguez-Pascua, Calvo, De Vicente and Gómez-Gras2000) but could also be related to progressive instability on the lake slope triggered by sediment-laden river floods entering the lacustrine body and continuing their run to the lake bottom (cf. Schäfer et al. Reference Schäfer, Rast, Stamm, Heling, Rothe, Forstner and Stoffers1990; Schäfer, Reference Schäfer, Baganz, Bartov, Bohacs and Nummedal2012). Upwards, more sandy deposits succeed, indicating a progressive shallowing of the environment, perhaps connected with the approach of a lacustrine delta. From the middle to the top of the ‘limnic’ successions, debris flows appear (cf. Talbot & Allen, Reference Talbot, Allen and Reading1996; Iverson, Reference Iverson1997), probably triggered by synsedimentary tectonics towards the end of the Late Pennsylvanian to early early Permian depositional cycle. The plane-parallel, almost non-erosive lower boundary of the debris flow conglomeratic events, their coarsening-upward passing upward to fining-upward trend, and the growing matrix content suggest they moved as supersaturated, pseudoplastic debris flows in a subaqueous environment compatible with hyperpycnal flows (cf. Nemec & Steel, Reference Nemec, Steel, Koster and Steel1984; Colella, Reference Colella, Nemec and Steel1988; Maizels, Reference Maizels1989; Mastalerz, Reference Mastalerz1995; Miall, Reference Miall1996). Their lens shape suggests channelized deposits. The intercalated sandstone–siltstone beds could be the topmost, final deposit of the event, or the following slack water deposit (cf. Miall, Reference Miall1996). The evidence of a significant sedimentary discontinuity between the Rio Su Luda Fm and the Mulargia Fm is inconclusive; thus, given the rapid alternation of mainly coarse grey-green and red deposits at their transition, the contact between those units should be interpreted as gradual, with a progressive change of the debris feeding due to evolving morphotectonic conditions. The latter could also have an influence in gradually modifying the local microclimate from wet to dry, as suggested by Costamagna (Reference Costamagna2019).

Fig. 23. Progressive changes of the sedimentological features in the different sectors of the Mulargia–Escalaplano Pennsylvanian–Permian basin. MW – Western Mulargia sector; ME – Eastern Mulargia sector; ES – Escalaplano sector. Geological base modified and redrawn from Funedda et al. (Reference Funedda, Carmignani, Pertusati, Uras, Pisanu and Murtas2008) and Pittau et al. (Reference Pittau, Del Rio and Funedda2008).

The progressive morphotectonic change could also explain the difference in dip intervening between the stratigraphic units. The dip gradually decreases upwards; this is visible along the Antoni Cauli stratigraphic section from bottom to top (Figs 3, 5, 7). Based on the reduced thickness of the Rio Su Luda Fm in the Mulargia sector in comparison with that of other coeval basins (e.g. 60 m versus 150 to 250 m in the Perdasdefogu basin; Ronchi et al. Reference Ronchi, Broutin, Diez, Freytet, Galtier and Lethiers1998; Costamagna, Reference Costamagna2019), and assuming no significant erosive thickness reduction took place later, subsidence at that time was still slow in this Variscan molassic basin.

The surveyed coded facies assemblages (Figs 7, 8, 10; Tables 1, 2) supported the presence in the Rio Su Luda Fm of channelized gravel bars and sediment gravity flows, with sandy bars and minor low-energy elements more related to lacustrine contexts (lake bottom and lacustrine delta); those architectural elements may be better referable to the fluvial models 1–2–3 of Miall (Reference Miall1985, Reference Miall1996; Table 3).

4.b.2. Upper Rotliegend Group: depositional environment

The Upper Rotliegend Group was initiated through the Mulargia Fm by conglomerates and breccias, indicating a noticeable increase in topographic differences and transporting energy (cf. Blair, Reference Blair1986; Blair & McPherson, Reference Blair and McPherson1994; see also Costamagna, Reference Costamagna2015, Reference Costamagna2016) possibly related to the formerly mentioned extensional tectonic climax (sensu Barrell, Reference Barrell1917; Blair & Bilodeau, Reference Blair and Bilodeau1988). Also, the scattered carbonate beds found on the western border of the West Mulargia sector close to the base of the Mulargia Fm evidence an abundance of immature debris (Fig. 20). The embedded pebbles from the Rio Su Luda Fm evidence erosion of the underlying sedimentary deposits. The short, ‘hybrid’ Melas–Genna Ureu succession (Figs 3, 5), resting directly over the Variscan basement, represents a remanent of a northern marginal area of the ‘limnic’ succession where sedimentation started possibly later in respect to the main outcrops of the Rio Su Luda Fm: its mixed characters in fact may actually represent the transition between the Rio Su Luda and the Mulargia Fm. The Upper Rotliegend Group in the western Mulargia sector rests (unconformably?) over and erodes the Rio Su Luda Fm. Otherwise, it lies unconformably over the Variscan basement. The development of small highs and lows on the transgressed (sensu Olsen, Reference Olsen and Katz1991) basement surface could be due to synsedimentary tectonic activity, documented by faults in some outcrops and suggested by frequent convolute laminations. The Upper Rotliegend Group is represented by two fining-upwards sedimentary cycles, separated by a slight unconformity, and each terminated with a volcanic depositional event. A basal conglomerate of the Pegulari Fm and the upper sedimentary sub-cycle evidences a renewed period of tectonomagmatic activity. The variable thickness of this basal level suggests the covering of an articulated morphology. The W–E angular-to-rounded and volcanic rock-prevalent pebble change suggests a directional trend. The renewed deposition of coarse-grained material from the previous sedimentary cycles points to cannibalistic processes and tectonic rejuvenation of the landscape, as described in the German Late Variscan Molasse by Schneider & Romer (Reference Schneider, Romer, Linnemann and Romer2010), and more generally stated for these kinds of basins by Blair & Bilodeau (Reference Blair and Bilodeau1988). According to Barca et al. (Reference Barca, Carmignani, Eltrudis and Franceschelli1995), the metamorphic pebbles forming the conglomerates and breccias of the Lower Rotliegend Group are related to erosion of the uppermost Variscan Meana Sardo Unit, while the pebbles embedded into the Upper Rotliegend Group are related to the deepest Variscan Riu Mulargia Unit (Riu Su Gruppa Unit in Carmignani et al. Reference Carmignani, Oggiano, Barca, Conti, Eltrudis, Funedda, Pasci and Salvadori2001) (Fig. 2). This erosive trend matches a general framework of a metamorphic basement undergoing uplift and unroofing (cf. Tucker, Reference Tucker2001; Garzanti et al. Reference Garzanti, Vezzoli, Lombardo, Ando’, Mauri, Monguzzi and Russo2004; Critelli, Reference Critelli2018).

Each cycle of the Upper Rotliegend Group is made up of alternations of pelitic and sandy-pebbly, tabular- to lens-shaped beds. They are interpreted as unchannelized to channelized deposits. In both cycles a fining-upward trend is apparent (Table 4). The lower Mulargia Fm is on average coarser and so it is related to a higher-energy environment if compared with the upper Pegulari Fm; this probably was related to a more marked preceding tectonomagmatic climax. Both the cycles are dominated by fine deposits embedding a distributary channel network showing spatial changes in depositional architecture due to changes in fluvial style (sensu Miall, Reference Miall1996, Reference Miall2014); the gradual decreasing width/thickness ratio of the channels in space (eastwards) and time testifies to that (Table 4). They represent alluvial systems with gradually decreasing energy, from small alluvial fans with local unchannelized deposits to alluvial plains with laterally migrating sinuous river channels (cf. Blair, Reference Blair1986; Miall, Reference Miall1996). The difference in the colour of the conglomerate/breccia beds (from reddish to rare grey-red) may be due to different source areas (cf. Boggs, Reference Boggs2009) from the Variscan basement and/or from previous late-orogenic depositional cycles completely dismantled by older erosive processes. Evidence of this can be found in rare quartzrudite pebbles incompatible with the sedimentary petrographic composition of the molassic deposits, and perhaps produced by older, completely dismantled erosive cycles. In the upper part of every sub-cycle, crevasse splays in the form of thin, tabular sandstone beds also exist (cf. Collinson, Reference Collinson and Reading1996; Miall, Reference Miall1996, Reference Miall2014). The depositional mechanisms varied from stream flows to clast-rich debris flows (cf. Nemec & Steel, Reference Nemec, Steel, Koster and Steel1984; Collinson, Reference Collinson and Reading1996; Miall, Reference Miall1996); settling is usually restricted to interchannel areas (cf. Miall, Reference Miall1996). Lowlands were also areas of playa lake deposition (Costamagna, Reference Costamagna2019). The occurrence of laminated clayey siltstones/mudstones with desiccation cracks and minor, locally pedogenized, carbonate beds (for the most part fenestral bindstones) with scattered evaporite crystals (Fig. 19) indicate mainly terrigenous, possibly ephemeral, shallow playa lakes under a hot-dry (arid to subarid) climate sporadically affected by strong rainfall events that produced significant shifts of the shoreline (cf. Rosen, Reference Rosen and Rosen1994; Deroin, Reference Deroin2008). Desiccation cracks suggest times of strong evaporation causing water level fall, shrinkage and finally exposure (cf. Lopez et al. Reference Lopez, Gand, Garric, Körner and Schneider2008). Late silicification of the carbonate beds may be related to coeval hydrothermal activity (Gaggero et al. Reference Gaggero, Gretter, Langone and Ronchi2017), or to the diagenesis of the evaporites leading to their pseudomorphosis (cf. Siedlecka, Reference Siedlecka1972).

The coded facies assemblages (Figs 10, 12, 13, 14, 16; Tables 1, 2) support in the Mulargia Fm the prevailing presence of channelized gravel bars and sediment gravity flows (Miall’s fluvial styles 1, less 2 and 3, Table 3: Miall, Reference Miall1985, Reference Miall1996), passing upwards to sandy bars embedded into overbank environment elements (Miall’s fluvial styles 9–11; Table 3). In the Pegulari Fm the only gravel bars are associated with the basal conglomerates (Miall’s fluvial style 1; Table 3). Upwards are sandy crevasse splays associated with overbank environment elements (Miall’s styles 6–7 and 9–11; Table 3).