1. Introduction

Detrital zircon U–Pb geochronology is commonly used for provenance analyses, providing information on sedimentary dispersal, basin evolution, palaeo-drainage systems, surface uplift and the tectonic setting during deposition (Rainbird et al. Reference Rainbird, Hamilton and Young2001; Kosler & Sylvester, Reference Kosler and Sylvester2003; Barth et al. Reference Barth, Wooden, Jacobson and Probst2004; Lawton et al. Reference Lawton, Bradford, Vega, Gehrels and Amato2009; Cawood et al. Reference Cawood, Hawkesworth and Dhuime2012; Shaanan et al. Reference Shaanan, Rosenbaum and Campbell2019). This methodology has been applied extensively in studies that aimed to understand the evolution of Mesozoic–Cenozoic basins in northeastern Asia, including the Sanjiang Basin (Fig. 1a; e.g. Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Chen, Batt, Dilek, Na, Sun, Yang, Meng and Zhao2015, Reference Zhang, Dilek, Chen, Yang and Meng2017). Despite the power of detrital zircon U–Pb dating, the approach has some inherent limitations. Firstly, its ability to detect mafic and ultramafic sources is limited due to the scarcity of zircon grains in such rocks. Secondly, detrital zircon U–Pb ages cannot distinguish between coeval igneous rocks that have been derived from different magmatic sources (Reiners et al. Reference Reiners, Campbell, Nicolescu, Allen, Hourigan, Garver, Mattinson and Cowan2005). Thirdly, the resilience of zircon grains and their ability to survive through multiple episodes of sedimentary recycling and transportation (Bruguier & Lancelet, Reference Bruguier and Lancelet1997; Cherniak & Watson, Reference Cherniak and Watson2000) means that the provenance of older detrital zircon grains (e.g. Neoproterozoic zircons) could be elusive and ambiguous. These limitations make it difficult to decipher the depositional history of the Sanjiang Basin and surface processes (e.g. uplift history) of the northeastern Asian continental margin.

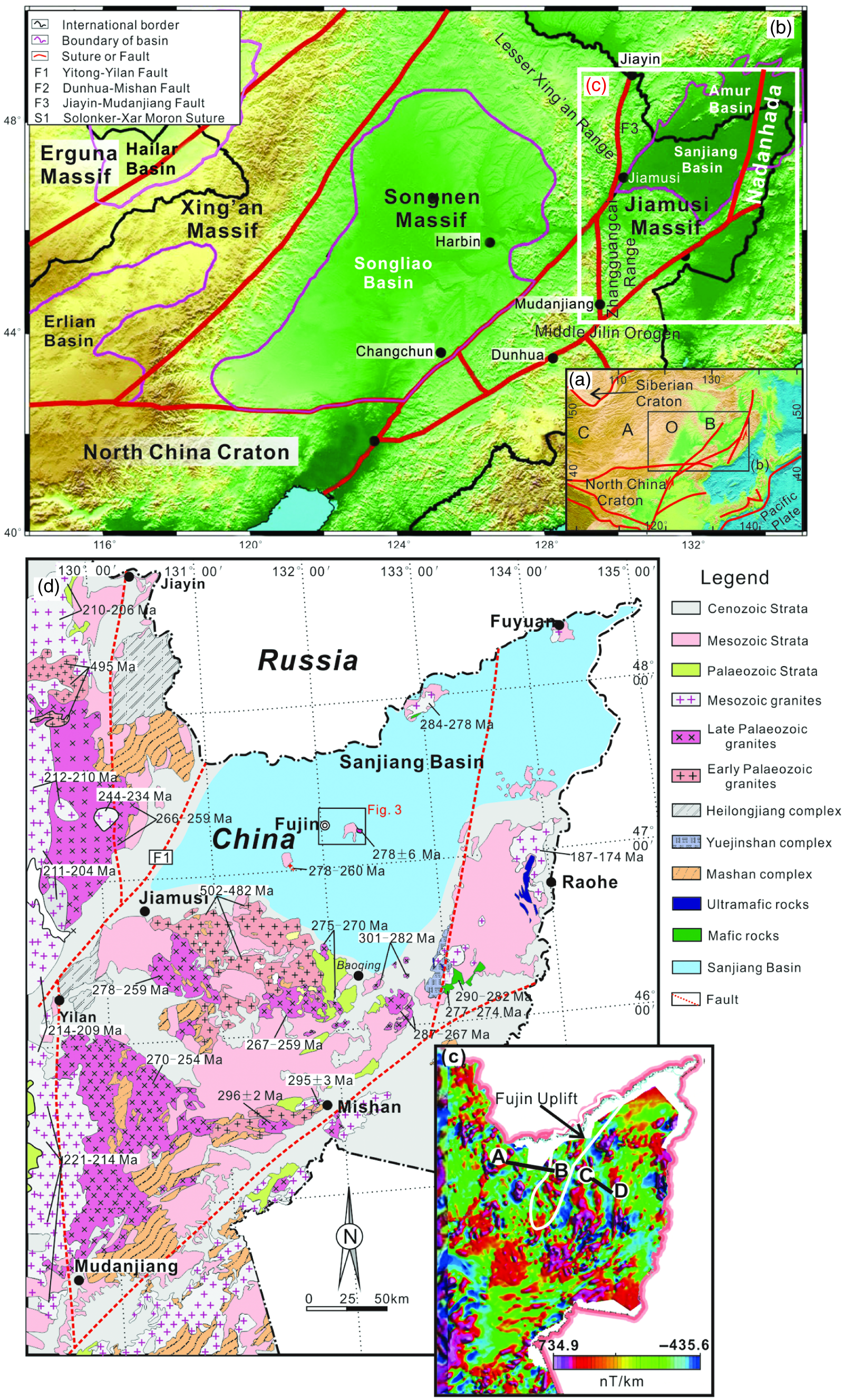

Fig. 1. Topographic and tectonic map of (a) northeastern Asia and (b) northeastern China (after Tao et al. Reference Tao, Niu, Ning, Chen, Grand, Kawakatsu, Tanaka, Obayashi and Ni2014); (c) aeromagnetic anomaly map of northeastern China; and (d) geological map of northeastern China showing the location of the Sanjiang Basin and the ages of igneous rocks (after Wu et al. Reference Wu, Sun, Ge, Zhang, Grant, Wilde and Jahn2011; Xu et al. Reference Xu, Pei, Wang, Meng, Ji, Yang and Wang2013).

The Sanjiang Basin is a large Mesozoic sedimentary basin overlying the basement of the Jiamusi Massif in the easternmost Central Asian Orogenic Belt (CAOB; Fig. 1a, b; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Chen, Yang, Feng, Wu, Batt, Zhao, Sun, A, Wang and Yang2012). Published detrital zircon U–Pb data indicate that the detrital material in the Sanjiang Basin was likely derived from multiple sources of similar ages (e.g. Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Chen, Batt, Dilek, Na, Sun, Yang, Meng and Zhao2015). While previous detrital zircon ages have provided valuable information on the provenance of some basinal strata (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Chen, Batt, Dilek, Na, Sun, Yang, Meng and Zhao2015), the provenance and depositional history of the Sanjiang Basin remain controversial, partly because of the inherent limitations of detrital zircon U–Pb geochronology. Understanding the provenance and depositional history of the Sanjiang Basin is crucial for reconstructing the uplift history of the northeastern Asian continental margin. To obtain a more diagnostic signature of the provenance region, complementary data from clastic sedimentary rocks and individual zircon grains must be used. Such data can be obtained, for example, from sandstone petrology (Dickinson & Suczek, Reference Dickinson and Suczek1979; Dickinson, Reference Dickinson and Zuffa1985), whole-rock geochemistry (e.g. Migani et al. Reference Migani, Borghesi and Dinelli2015), trace-element composition of zircon grains (e.g. Belousova et al. Reference Belousova, Griffin, O’Reilly and Fisher2002; Rubatto, Reference Rubatto2002; Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Rosenbaum, Allen and Mortimer2020), zircon morphology (e.g. Pidgeon et al. Reference Pidgeon, Nemchin and Hitchen1998; Shaanan & Rosenbaum, Reference Shaanan and Rosenbaum2018) and zircon Hf isotope geochemistry (Hawkesworth & Kemp, Reference Hawkesworth and Kemp2006). Sandstone petrology can provide information on the hydrodynamic conditions during sedimentary transport, as well as the tectonic setting of the source regions (Dickinson, Reference Dickinson and Zuffa1985). Whole-rock geochemistry of the sedimentary rocks can provide information on the weathering history, sedimentary recycling and the tectonic setting of the source terranes (Roser & Korsch, Reference Roser and Korsch1986; Armstrong-Altrin et al. Reference Armstrong-Altrin, Lee, Verma and Ramasamy2004). Hf isotope analyses can provide constraints on crustal recycling, with derived model Hf ages constraining the timing of extraction from a mantle reservoir.

In this paper, we present sandstone petrography and whole-rock geochemistry results from the Sanjiang Basin, complemented by detrital zircon U–Pb ages and in situ Hf isotope data. Combined with available data from exploratory drilling and seismic profiles, our results elucidate the provenance and sedimentary history of the Sanjiang Basin and provide a new insight into the uplift history of the northeastern Asian continental margin.

2. Geological setting

The study area in northeastern China belongs to the eastern part of the CAOB and is bounded by the Siberian and North China cratons (Fig. 1a, b; Kröner et al. Reference Kröner, Kovach, Belousova, Hegner, Armstrong, Dolgopolova, Seltmann, Alexeiev, Hoffmann, Wong, Sun, Cai, Wang, Tong, Wilde, Degtyarev and Rytsk2014; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Windley, Sun, Li, Huang, Han, Yuan, Sun and Chen2015). The basement geology in this area includes a number of Proterozoic massifs and terranes, such as the Erguna Massif, Xing’an Massif, Songnen Massif, Jiamusi Massif and Nadanhada Terrane (Fig. 1b; Sengör et al. Reference Sengör, Natal’in and Burtman1993; Wu et al. Reference Wu, Sun, Ge, Zhang, Grant, Wilde and Jahn2011; Han et al. Reference Han, Zhou, Li and Song2017; Luan et al. Reference Luan, Wang, Xu, Ge, Sorokin, Wang and Guo2017 a, b, Reference Luan, Yu, Yu, Cui and Xu2019; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Ge, Bi, Wang, Tian, Dong and Chen2018). During the Mesozoic Era, the area was subjected to widespread crustal extension, indicated by abundant fault-bounded sedimentary basins, metamorphic core complexes and intraplate magmatism (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Zheng, Zhang, Zeng, Donskaya, Guo and Li2011; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Yan and Ji2019). Major graben-hosted basins in the area include the Sanjiang, Songliao, Erlian and Hailar basins (Fig. 1b). The easternmost basin, Sanjiang Basin, is located close to the Circum-Pacific subduction zone and has been regarded as a typical Mesozoic retro-arc foreland basin (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Dilek, Chen, Yang and Meng2017).

The Sanjiang Basin is situated along the China–Russia border, with its northern part (in Russia) called Amur Basin (Fig. 1b). The basin is surrounded by Mesozoic orogens (Lesser Xing’an Range, Zhangguangcai Range, Middle Jilin Orogen) and the Nadanhada Terrane (Fig. 1b). The area includes abundant igneous plutons of various ages (Fig. 1c, d), including early Palaeozoic (Wilde et al. Reference Wilde, Zhang and Wu2000, Reference Wilde, Wu and Zhang2003; Bi et al. Reference Bi, Ge, Yang, Zhao, Yu, Zhang, Wang and Tian2014 a; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Ge, Zhao, Bi, Wang, Dong and Xu2017), Permian (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Sun, Ge, Zhang, Grant, Wilde and Jahn2011; Bi et al. Reference Bi, Ge, Zhang, Yang and Wang2014 b, Reference Bi, Ge, Yang, Zhao, Xu and Wang2015; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Ge, Zhao, Yu and Zhang2015 b) and Triassic (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Ge, Zhao, Dong, Xu, Wang, Ji and Yu2015 a, b; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Xu, Yu, Wang, Tang and Li2016). A few Neoproterozoic and Early Cretaceous igneous rocks also occur in the region (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Sun, Ge, Zhang, Grant, Wilde and Jahn2011; Luan et al. Reference Luan, Xu, Wang, Wang and Guo2017 b, Reference Luan, Yu, Yu, Cui and Xu2019; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Ge, Zhao, Bi, Wang, Dong and Xu2017, Reference Yang, Ge, Bi, Wang, Tian, Dong and Chen2018). The Mashan, Heilongjiang and Yuejinshan complexes are three metamorphic complexes in the study area (Fig. 1d).

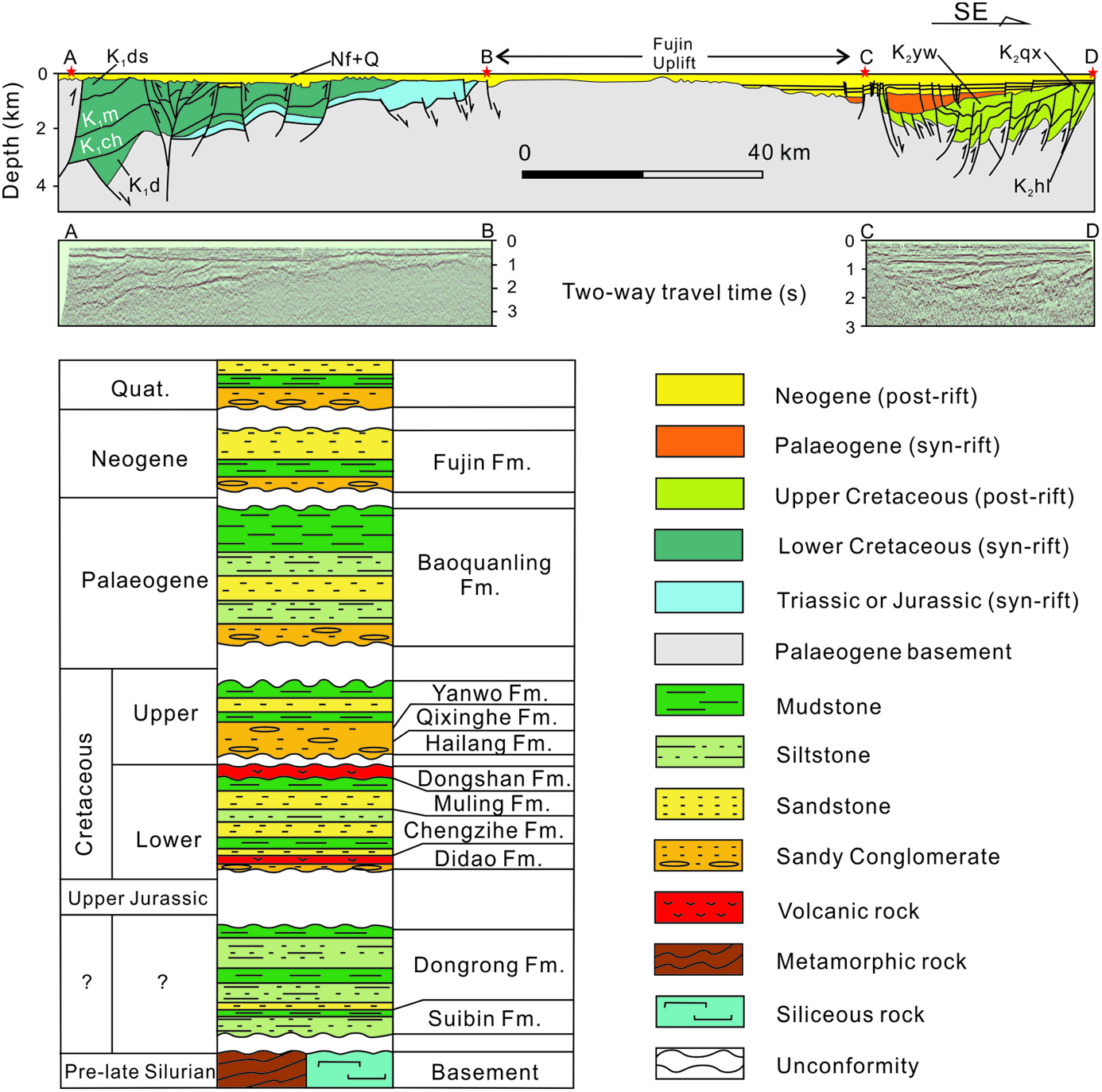

Based on aeromagnetic and seismic data, the Sanjiang Basin can be divided into two sub-basins, separated by the so-called Fujin Uplift (Figs 1c, 2; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Chen, Yang, Feng, Wu, Batt, Zhao, Sun, A, Wang and Yang2012, Reference Zhang, Dilek, Chen, Yang and Meng2017). The basin fill includes Mesozoic and Cenozoic terrestrial strata, consisting of volcanic, volcaniclastic, alluvial-fan, fluvial and lacustrine sediments (Fig. 2; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Chen, Batt, Dilek, Na, Sun, Yang, Meng and Zhao2015). The thickness of the sedimentary succession is variable, reaching a maximum of c. 9 km in the depocentre. Mesozoic strata include, in ascending order, the Suibin, Dongrong, Didao (K1d), Chengzihe (K1ch), Muling (K1m), Dongshan (K1ds), Hailang (K2hl), Qixinghe (K2qx) and Yanwo (K2yw) formations (Fig. 2). Cenozoic strata include the Baoquanling (Eb) and Fujin (Ef) formations. Exploratory drilling identified five unconformities within the Mesozoic–Cenozoic stratigraphic succession (Fig. 2; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Chen, Yang, Feng, Wu, Batt, Zhao, Sun, A, Wang and Yang2012).

Fig. 2. Cross-section and stratigraphy of the Sanjiang Basin (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Dilek, Chen, Yang and Meng2017). Locations of seismic profiles are shown in Figure 1c.

3. Samples and analytical methods

We measured two sections near Fujin (Fig. 1d). Section I (47° 19ʼ 37ʼʼ N, 132° 28ʼ 18ʼʼ E) is dominated by grey and black mudstone, sandstone and pebbly sandstone, with thin siltstone and silty mudstone layers (Fig. 3). Rocks in Section I contain bivalve and plant fossils, suggesting a paralic depositional environment. Based on the fossil assemblage, we consider that Section I belongs to the Dongrong Formation (Fig. 2). Section II (47° 12ʼ 42ʼʼ N, 132° 13ʼ 02ʼʼ E) consists of green mudstone, grey siltstone and medium sandstone, as well as interbedded grey mudstone and silty mudstone (Fig. 3). Based on the palynological record from this section (Aquiapollenites sp., Cyathidites sp., Cicatricosisporites sp. and Protoconiferus), we consider that Section II belongs to the Yanwo Formation (Fig. 2). The Yanwo Formation is intruded by 56–50 Ma granites (Fig. 4a, b; Li et al. Reference Li, Liu, Li, Zhao, Shi, Li and Yang2019). We collected 26 samples from the two sections for petrographic and whole-rock geochemical analysis. In addition, three samples were used for zircon U–Pb and Hf isotopic analysis. Mesozoic plant fossils (Cladophlebis and Podozamites) were found in two samples from the Dongrong Formation (Fig. 4c, d).

Fig. 3. (a) Detailed geological map of study area; and (b) measured geological sections of the Dongrong and Yanwo formations.

Fig. 4. Photographs showing (a) intrusive relationship; and (b) 50–55 Ma granite. Photomicrograph of (c) Cladophlebis fossil; (d) Podozamites fossil; (e) selected sandstone samples (cross-polarized light); (f) andesitic fragment; (g) felsic fragment; and (h) metamorphosed felsic lithic fragment. Lv – volcanic lithic fragment; Lm – metamorphic lithic fragment.

Six thin-sections from sandstone samples were selected for petrographic analysis using a microscope with an attached point-counting stage. In each sample, at least 300 points were counted following the Gazzi–Dickinson method (Ingersoll et al. Reference Ingersoll, Fullard, Ford, Grimm, Pickle and Sares1984; Dickinson, Reference Dickinson and Zuffa1985). Recorded components include monocrystalline quartz (Qm), polycrystalline quartz (Qp), plagioclase (P), alkali feldspar (Kf) and lithic fragments (L). Matrix and cement were not counted but estimated using standard charts for visual percentage estimation. The results are presented in online Supplementary Table S1 (available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo and https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/nfy7gxg38p/1).

Samples for whole-rock analysis were crushed in a c. 200 μm mesh using an agate mill. The samples were then digested in Teflonbombs and measured by X-ray fluorescence (Rigaku RIX 2100 spectrometer), fused-glass disks and an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS) (Agilent 7500a). Standard samples used were BHVO-1 (basalt), BCR-2 (basalt) and AGV-1 (andesite). Analytical results for these standards indicate that the analytical uncertainties are less than 3%, and the analytical precision for major and trace elements is better than 5% and 10%, respectively (Rudnick et al. Reference Rudnick, Gao, Ling, Liu and Mc Donough2004). The whole-rock geochemical analyses were conducted at the State Key Laboratory of Geological Processes and Mineral Resources at the China University of Geosciences (Wuhan, China). Major- and trace-element results are provided in online Supplementary Table S2 (available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo and https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/nfy7gxg38p/1).

Zircon grains were extracted by standard density and magnetic separation techniques, followed by handpicking under a binocular microscope. Cathodoluminescence (CL) images were obtained to reveal internal structures within the zircon grains. Zircon U–Pb analyses were performed using an Agilent 7500a ICP-MS equipped with a 193 nm laser. The analyses created a crater diameter of 32 μm. For further information on the analytical procedures, see Yuan et al. (Reference Yuan, Gao, Liu, Li, Günther and Wu2004). Data reduction and correction for common Pb were done following the methods by Anderson (Reference Anderson2002), Ludwig (Reference Ludwig2003) and Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Gao, Hu, Gao, Zong and Wang2010). In situ zircon Hf isotope analyses were conducted using a Neptune multi-collector (MC-) ICP-MS. By modifying the X skimmer cone during the experiment, the signal intensities of Yb, Lu and Hf were improved by factors of 5.3, 4.0 and 2.4, respectively. The crater diameter of the single spot ablation was 44 μm. For further information about the operating conditions, see Hu et al. (Reference Hu, Liu, Gao, Hu, Dietiker and Günther2008, Reference Hu, Liu, Gao, Liu, Yang, Zhang, Tong, Lin, Zong, Li, Chen and Zhou2012). Zircon U–Pb dating and Hf isotope analyses were performed at Wuhan SampleSolution Analytical Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Zircon U–Pb ages and Hf isotope results are provided in online Supplementary Tables S3 and Table S4 (available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo and https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/nfy7gxg38p/1), respectively.

4. Results

4.a. Sandstone petrography

All sandstone samples are arkoses and wackes (Fig. 5; online Supplementary Table S1), composed mainly of monocrystalline quartz, plagioclase and volcanic lithic fragments with minor polycrystalline quartz, K-feldspar and metamorphic lithic fragments (Fig. 4e–h). Quartz grains are moderately sorted and are sub-rounded to sub-angular (Fig. 4e). Feldspar grains are sub-rounded, and some plagioclase grains are altered into sericite (Fig. 4e). Volcanic lithic fragments consist of andesitic (Fig. 4f) and felsic fragments (Fig. 4g), as well as minor amounts of metamorphosed felsic lithic fragments (Fig. 4h). Biotite grains were observed in the wacke samples. Based on the degree of sorting and mineral morphology, the sandstone samples are considered compositionally and texturally immature.

Fig. 5. Lithological classification of siliciclastic rocks (Herron, Reference Herron1988). The grey symbols correspond to samples from Cao et al. (Reference Cao, Guo, Shan, Ma and Sun2015) and Hu et al. (Reference Hu, Meng and Liu2021).

4.b. Whole-rock geochemistry

Samples from the Dongrong and Yanwo formations show variable major-element compositions (online Supplementary Table S2). Medium- and fine-grained wackes and arkoses are characterized by relatively high concentrations of SiO2 (64.2–74.5 wt%), CaO (0.80–5.20 wt%), Na2O (2.28–3.83 wt%) and K2O (3.17–3.93 wt%), and low concentrations of Al2O3 (12.1–14.9 wt%), total Fe2O3 (1.65–3.27 wt%), TiO2 (0.30–0.66 wt%) and P2O5 (0.08–0.19 wt%). In contrast, siltstones and mudstones have relatively low concentrations of SiO2 (40.0–61.7 wt%), total Fe2O3 (1.90–6.50 wt%), MgO (0.70–1.42 wt%), K2O (0.22–1.62 wt%) and MnO (0.01–0.02 wt%); high concentrations of Al2O3 (14.6–24.8 wt%) and Na2O (1.30–3.60 wt%); and variable concentrations of CaO (0.50–2.40 wt%), TiO2 (0.66–1.15 wt%) and P2O5 (0.04–0.31 wt%). Samples 14JP1 and 14JP2, from the Dongrong Formation yielded chemical indices of alteration (CIA) of 43.2–84.8, plagioclase indices of alteration (PIA) of 42.3–85.6, and indices of compositional variability (ICV) of 0.34–1.12 (Fig. 6; online Supplementary Table S2). Sample 14JP3 from the Yanwo Formation yielded CIA, PIA and ICV values of 44.2–83.6, 43.5–84.3 and 0.30–1.05, respectively (Fig. 6; online Supplementary Table S2).

Fig. 6. (a) CIA–ICV diagram for sedimentary rocks from the Sanjiang Basin (Nesbitt & Young, Reference Nesbitt and Young1989; Cox et al. Reference Cox, Lowe and Cullers1995). (b) A–CN–K diagram for sedimentary rocks from the Sanjiang Basin (Fedo et al. Reference Fedo, Nesbitt and Young1995). Symbols as for Figure 5. The grey symbols correspond to samples from Cao et al. (Reference Cao, Guo, Shan, Ma and Sun2015) and Hu et al. (Reference Hu, Meng and Liu2021).

All samples are enriched in light rare earth elements (LREE) and depleted in heavy rare earth elements (HREE), with chondrite-normalized La/Yb (La/YbN) values of 4.8–14.1 (Fig. 7a; online Supplementary Table S2). The samples show various degrees of negative Eu anomaly (Eu/Eu* = 0.30–0.75), and compositional variations in both high-field-strength elements (HFSE) and large-ion-lithophile elements (LILE). Most samples are enriched in HFSE (e.g. Th, Zr and Hf) and depleted in LILE (e.g. Ba, K and Sr), P and Ti. Some samples (e.g. 14JP2 and 14JP3) show variable concentrations of Ba, K, La and Zr (Fig. 7b; online Supplementary Table S2). All samples have relatively low concentrations of transition metals, such as Cr, Ni, Cu and Sc (online Supplementary Table S2).

Fig. 7. (a) Chondrite-normalized REE patterns and (b) primitive mantle (PM) normalized trace-element diagrams. The chondrite and PM values used for normalization are from Boynton (Reference Boynton and Henderson1984) and Sun & McDonough (Reference Sun, McDonough, Saunders and Norry1989), respectively.

4.c. Detrital zircon U–Pb geochronology and Hf isotope analysis

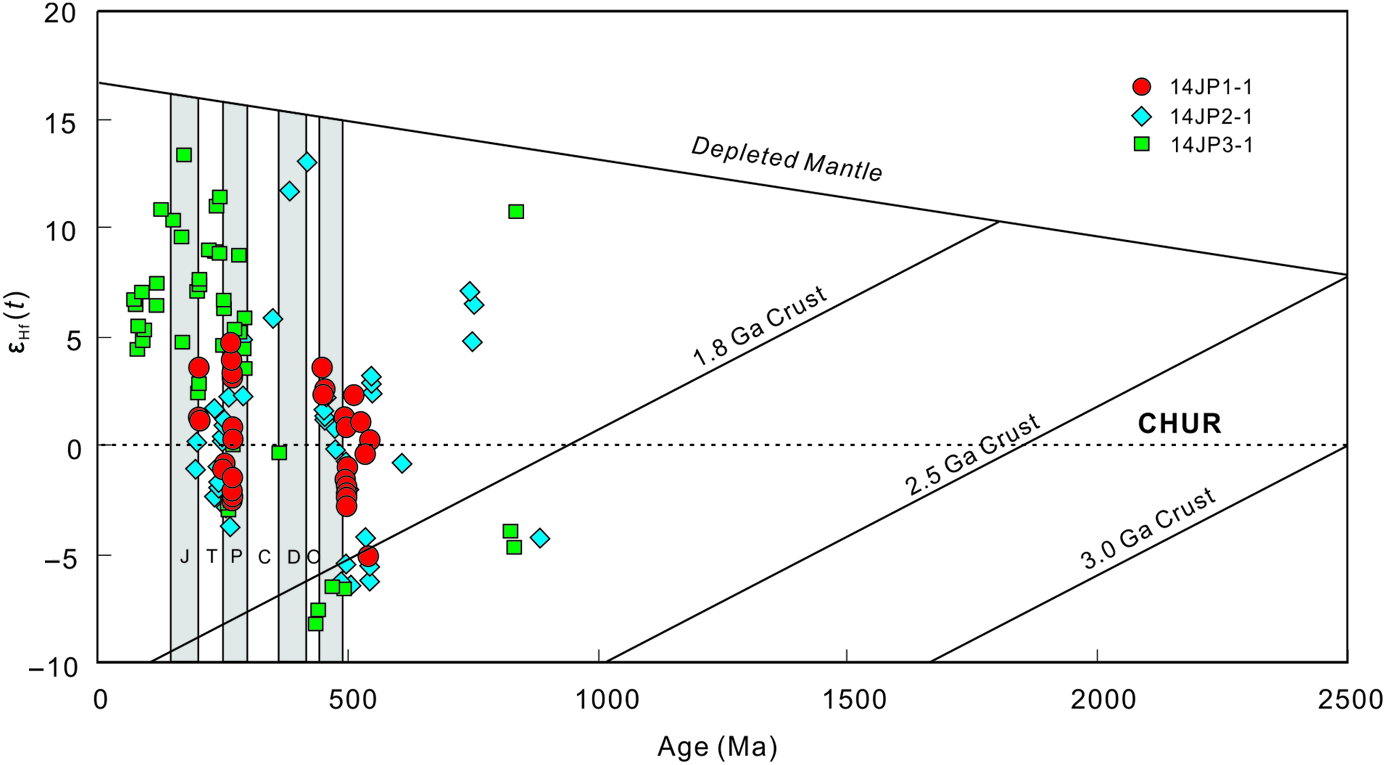

From each of the three samples selected for U–Pb dating, more than 100 detrital zircon grains were dated. The results yielded 320 concordant ages. Out of these zircon grains (with determined U–Pb ages), 133 grains were analysed for Hf isotopic compositions. The results are presented in online Supplementary Tables S3 and S4. 206Pb/238U ages are used for grains younger than 1000 Ma. For statistical purposes, ages with discordance of > 10% were excluded. Most detrital zircon grains are euhedral–subhedral and display banded structures or oscillatory growth zoning (Fig. 8a–c). They are generally characterized by high Th/U ratios (≥ 0.1), with the exception of four grains that yielded Th/U ratios of 0.05–0.08. As evidenced by the zircon morphology and the high Th/U ratios (online Supplementary Table S3), most of the detrital zircon grains are interpreted as originating from a magmatic source (Belousova et al. Reference Belousova, Griffin, O’Reilly and Fisher2002; Rubatto, Reference Rubatto2002).

Fig. 8. Representative cathodoluminescence (CL) images of selected zircons and zircon U–Pb concordia diagrams of the Dongrong and Yanwo formations. Red and dotted circles on the zircon grains indicate locations of the analysis spots used for LA-ICP-MS U–Pb dating and Hf isotopic analyses, respectively.

4.c.1. Sample 14JP1-1

A total of 106 analytical spot analyses were conducted on 106 grains from sample 14JP1-1. The results yielded five main concordant 206Pb/238U age populations: 548–493 Ma (n = 38), c. 454 Ma (mean square weighted deviation (MSWD) = 0.01, n = 6), 291–254 Ma (n = 45), 241–227 Ma (n = 4) and 208 ± 2 Ma (MSWD = 0.55, n = 6) (online Supplementary Table S3; Fig. 8d). In addition, seven grains yielded 206Pb/238U ages of 929 ± 15, 895 ± 10, 847 ± 11, 726 ± 8, 369 ± 5, 358 ± 5 and 336 ± 4 Ma. The youngest concordant detrital zircon age is 206 ± 3 Ma.

The ϵHf(t) values are divided into different groups based on the U–Pb ages of the zircon grains (online Supplementary Table S4). Cambrian zircon grains (548–493 Ma) yielded ϵHf(t) values between −5.1 and +2.3, with corresponding two-stage model ages (T DM2) of 1824–1333 Ma (Fig. 9; online Supplementary Table S4). Ordovician zircon grains (c. 455 Ma) yielded ϵHf(t) values of 2.6–3.5, with corresponding T DM2 of 1285–1207 Ma (Fig. 9; online Supplementary Table S4). Permian zircon grains (291–254 Ma) yielded ϵHf(t) values between −2.4 and +4.7, with corresponding T DM2 of 1441–1238 Ma (Fig. 9; online Supplementary Table S4). Late Triassic (208–206 Ma) zircon grains yielded ϵHf(t) values of between +1.0 and +3.6, with corresponding T DM2 of 1177–1017 Ma (Fig. 9; online Supplementary Table S4).

Fig. 9. Correlations between Hf isotopic compositions and ages of detrital zircons from the Dongrong and Yanwo formations. J – Jurassic; T – Triassic; P – Permian; C – Carboniferous; D – Devonian; O – Ordovician.

4.c.2. Sample 14JP2-1

A total of 114 analytical spot analyses were conducted on 114 grains (online Supplementary Table S3; Fig. 8). The results yielded four major concordant 206Pb/238U age populations: 548 ± 3 Ma (MSWD = 0.91, n = 15), 524–451 Ma (n = 52), 298–257 Ma (n = 26) and 242 ± 3 Ma (MSWD = 2.4, n = 8). Additional minor age populations are: 750 ± 14 Ma (MSWD = 0.12, n = 3), 422 ± 6 Ma (MSWD = 0.01, n = 2), 223 ± 5 Ma (MSWD = 0.16, n = 2) and 201 ± 3 Ma (MSWD = 0.18, n = 3). Three grains yielded 206Pb/238U ages of 886 ± 12, 387 ± 5 and 353 ± 5 Ma. The youngest concordant age is 199 ± 3 Ma.

Neoproterozoic zircon grains dated at c. 886 Ma and 755–747 Ma yielded ϵHf(t) values of c. −4.3 and 4.7–7.0, respectively (Fig. 9; online Supplementary Table S4). Zircon grains dated at c. 548 Ma yielded ϵHf(t) values ranging between −6.3 and +3.0, with corresponding T DM2 of 1897–1317 Ma (Fig. 9; online Supplementary Table S4). Cambrian (505–499 Ma) zircon grains yielded ϵHf(t) values between −6.5 and −0.9, with corresponding T DM2 of 1882–1557 Ma (Fig. 9; online Supplementary Table S4). Ordovician (478–456 Ma) zircon grains yielded ϵHf(t) values between −0.3 and +2.1, with corresponding T DM2 of 1487–1302 Ma (Fig. 9; online Supplementary Table S4). Silurian (c. 421 Ma) zircon grains yielded ϵHf(t) and TDM2 values of 13 and 539 Ma, respectively. The two Devonian zircon grains (387 and 353 Ma) yielded ϵHf(t) values of 11.6 and 5.8, respectively (Fig. 9; online Supplementary Table S4). Permian (297–249 Ma) zircon grains yielded ϵHf(t) values between −3.8 and +4.8, with corresponding T DM2 of 1528–1001 Ma (Fig. 9; online Supplementary Table S4). Triassic (246–199 Ma) zircon grains yielded ϵHf(t) values between −2.4 and +1.6, with corresponding T DM2 of 1431–1169 Ma (Fig. 9; online Supplementary Table S4).

4.c.3. Sample 14JP3-1

A total of 100 analytical spot analyses were conducted on 100 grains. The results yielded seven major concordant 206Pb/238U age populations: 446 ± 5 Ma (MSWD = 1.06, n = 5), 299–254 Ma (n = 33), 252–235 Ma (n = 16), 208 ± 2 Ma (MSWD = 0.55, n = 6), 172 ± 4 Ma (MSWD = 1.7, n = 5), 95 ± 4 Ma (MSWD = 2.1, n = 5) and 85 ± 1 Ma (MSWD = 1.1, n = 16) (online Supplementary Table S3; Fig. 8c). Three additional minor age populations are 836 ± 12 Ma (MSWD = 0.33, n = 3), 367 ± 12 Ma (MSWD = 0.33, n = 2) and 121 ± 2 Ma (MSWD = 0.33, n = 3). Six grains yielded 206Pb/238U ages of 898 ± 9, 497 ± 6, 473 ± 6, 307 ± 4, 155 ± 5 and 131 ± 5 Ma. The youngest concordant detrital zircon age is 84 ± 1 Ma.

Neoproterozoic (c. 841 Ma) zircon grains are characterized by a wide variation of ϵHf(t) values (−4.7 to 10.7), and corresponding T DM2 range from 2013 to 1033 Ma (Fig. 9; online Supplementary Table S4). Ordovician–Devonian zircon grains are characterized by a narrower distribution of ϵHf(t) values (between −8.2 and −6.5), except for a single 367 Ma zircon that has an ϵHf(t) value of −0.4 (Fig. 9; online Supplementary Table S4). Permian (299–252 Ma) zircon grains, which are the most dominant zircon age population in sample 13JP3-1, yielded a wide variation of ϵHf(t) values ranging from 3.0 to 9.9, with corresponding T DM2 of 1475–647 Ma (Fig. 9; online Supplementary Table S4). Triassic–Cretaceous zircon grains are characterized by positive ϵHf(t) values. Triassic grains yielded ϵHf(t) values of 2.4–11.4, and their T DM2 ranged from 1440 to 552 Ma. Jurassic and Cretaceous zircons yielded ϵHf(t) values of 4.7–13.3 and 4.5–10.8; their corresponding T DM2 are 917–343 Ma and 875–487 Ma, respectively (Fig. 9; online Supplementary Table S4).

5. Discussion

5.a. Timing of deposition

Our results provide new constraints on the sedimentary history of the Sanjiang Basin. Previous detrital zircon geochronological studies have focused mainly on Cretaceous petroleum- and coal-bearing strata collected from boreholes in the Sanjiang Basin (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Chen, Batt, Dilek, Na, Sun, Yang, Meng and Zhao2015), but the depositional ages of exposed outcrops have remained poorly constrained. In fact, the two sections studied here, in the Fujin Uplift, have previously been considered as lower Permian strata (HBGMR, 1993). Our geological investigation and stratigraphic correlations indicate that these rocks belong to the Dongrong and Yanwo formations, respectively (Figs 1d, 2, 3). Furthermore, the discovery of Cladophlebis and Podozamites fossil assemblages in the Dongrong Formation (Fig. 4a, b) indicates that the age of the Dongrong Formation must be Mesozoic (Ash, Reference Ash1993; Falcon-Lang, Reference Falcon-Lang2002; Vavrek & Larsson, Reference Vavrek and Larsson2007). Our new detrital zircon data support this conclusion.

Sample 14JP1 from the lower part of the Dongrong Formation yielded a youngest concordant age peak of 208 ± 2 Ma. Sample 14JP2, from the middle part of the same formation, yielded a youngest concordant age peak of 201 ± 3 Ma. These Late Triassic ages provide a maximum depositional age constraint for the Dongrong Formation.

Sample 14JP3, from the bottom of the Yanwo Formation, yielded a youngest concordant age peak of 85 ± 1 Ma. This age provides a maximum depositional age constraint for this formation. The Yanwo Formation is intruded by a granodiorite body dated 54 ± 1 Ma (Fig. 4a, b; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Yang, Ge, Bi, Zhang and Xu2016a; Li et al. Reference Li, Liu, Li, Zhao, Shi, Li and Yang2019). The Yanwo Formation must therefore have been deposited after 85 Ma and before 54 Ma.

5.b. Depositional history

The depositional history of clastic sedimentary rocks typically involves weathering (Nesbitt & Young, Reference Nesbitt and Young1982), hydrodynamic sorting during transport (McLennan et al. Reference McLennan, Hemming, Mcdaniel, Hanson, Johnsson and Basu1993; Cullers, Reference Cullers1994), sedimentary recycling (Long et al. Reference Long, Sun, Yuan, Xiao and Cai2008) and diagenesis (Fedo et al. Reference Fedo, Nesbitt and Young1995, Reference Fedo, Eriksson and Krogstad1996). These processes control the chemical composition of detrital sediments. Using our petrographic and geochemical data, we discuss the effects of the above geological processes during the deposition of the Sanjiang Basin.

5.b.1. Weathering and sedimentary recycling

CIA and PIA are geochemical proxies that can be used to quantify the intensity of weathering in the source region (Nesbitt, Reference Nesbitt1979; Fedo et al. Reference Fedo, Nesbitt and Young1995). CIA values from the Dongrong Formation (43.2–84.8, with higher values in the upper part; online Supplementary Table S2) are generally higher than those found in the upper continental crust (UCC; CIA = 48; Rudnick & Gao, Reference Rudnick, Gao, Holland and Turekian2003), but lower than post-Archean Australian shale (PAAS; CIA = 70; McLennan et al. Reference McLennan, Hemming, Mcdaniel, Hanson, Johnsson and Basu1993). The results indicate that weathering was intensified during the deposition of the Dongrong Formation. PIA values from the same samples range from 42.3 to 85.6, and also show higher values in the upper part of the formation (online Supplementary Table S2), supporting our conclusion. Similarly, variations in the ICV values also indicate that the degree of weathering has increased from bottom to top. ICV values in sample 14JP1, which are generally higher than PAAS (ICV = 0.84; Fig. 6a), are typical values for an early stage of weathering (Fedo et al. Reference Fedo, Nesbitt and Young1995). In contrast, the lower ICV values (Fig. 6a) and relatively higher Al2O3 content (Fig. 6b) in sample 14JP2 from the upper part of the Dongrong Formation suggest an advanced stage of weathering. We therefore conclude that the provenance of the Dongrong Formation was initially weak weathering processes. During the deposition of this formation, an increase in the intensity of weathering processes produced compositionally mature alumina-rich sediments.

Sample 14JP3 from the Yanwo Formation yielded PIA, ICV and CIA values of 43.5–84.3, 0.30–1.05 and 44.2–83.6, respectively (Fig. 6; online Supplementary Table S2). These geochemical proxies suggest that the weathering processes, which affected the sources of the Yanwo Formation, were intensified during the deposition of this formation.

Sedimentary recycling in oxidizing conditions commonly results in fractionation of Th and U, because U4+ is readily oxidized to U6+ during weathering (McLennan & Taylor, Reference McLennan and Taylor1980). The removal of relatively soluble U6+ could cause an increase in the Th/U ratio; the Th/U ratio is therefore a good indicator for sedimentary recycling. The Mo/U molar ratio and Mo enrichment factor (MoEF) of sediments are good indicators of the redox conditions of water (Algeo & Tribovillard, Reference Algeo and Tribovillard2009). Under oxic conditions, Mo enrichment is limited and Mo is present as the stable and largely unreactive molybdate oxyanion (MoO42–). Our samples have lower Mo/U molar ratios than suboxic modern seawater (c. 7.5–7.9) with low MoEF (< 3.2), suggesting oxidizing conditions. The Th/U ratios of Unite A2 and Unite B show a positive correlation with the CIA values (Fig. 10; online Supplementary Table S2). Some of the measured Th/U ratios are higher than the average value for PAAS (4.7; McLennan & Taylor, Reference McLennan and Taylor1980), suggesting that parts of the provenance were derived from recycled sediments. These samples are also enriched in Zr (online Supplementary Table S2), which is another indication for the incorporation of recycled weathered material (recycling causes enrichment in heavy minerals, such as zircon and monazite).

Fig. 10. Th/U–CIA diagrams for the Dongrong and Yanwo formations. Symbols as for Figure 5.

5.b.2. Hydrodynamic sorting

The hydrodynamic conditions can be evaluated by textural maturity with respect to grain sizes and shapes, as well as mineralogical and geochemical compositions (McLennan et al. Reference McLennan, Hemming, Mcdaniel, Hanson, Johnsson and Basu1993). The six medium-grained arkose and wacke samples studied by us are compositionally and texturally immature, reflecting a low degree of sedimentary sorting. Geochemically, the samples are characterized by low contents of Al2O3 and high SiO2/Al2O3, suggesting low proportions of aluminous clay minerals. Furthermore, the low contents of HFSE (Zr and Hf), REE and transition metals (Cr and Sc) suggest that heavy minerals are rare or absent. Given that aluminous clay minerals and heavy minerals typically accumulate by sedimentary sorting, our observations support the suggestion that the sediments experienced a low degree of sedimentary sorting, likely associated with a relatively short distance of transport from the area of provenance.

5.b.3. Diagenesis

The geochemistry of sedimentary rocks can be affected by potassium metasomatism and silicification. Potassium metasomatism in sandstone could involve the conversion of aluminous clay minerals (e.g. kaolinite) to illite and/or conversion of plagioclase to K-feldspar (Fedo et al. Reference Fedo, Nesbitt and Young1995). In mudstone, potassium metasomatism is mainly associated with clay alteration. The latter can be identified petrographically by observing illite either in matrix or as an alteration product of partially weathered plagioclase grains. Such features were not observed in our samples. The role of potassium metasomatism can also be evaluated using the A-CN-K plot, with the expectation that samples subjected to this process would be distributed along a path towards the K2O apex of the triangle. This is not the case in our samples, which are depleted in K2O (Fig. 6b). We therefore conclude that our samples did not experience significant potassium metasomatism.

The recognition of polycrystalline quartz in the matrix (Fig. 4c) is indicative of silicification. Further evidence of silicification is metamorphic lithic fragments, which are characterized by polycrystalline quartz (Fig. 3f). The significantly higher SiO2/Al2O3 values in samples 14JP1-4 and 14JP3-6, in comparison with other samples with the same lithology (online Supplementary Table S2), might also be attributed to the process of silicification.

5.c. Interpretation of geochemical proxies

Major element geochemical proxies (e.g. K2O/Al2O3, SiO2/Al2O3 and A-CN-K) are commonly used to obtain information on the composition of source rocks (Nesbitt, Reference Nesbitt1979; Cox et al. Reference Cox, Lowe and Cullers1995; Fedo et al. Reference Fedo, Nesbitt and Young1995; Hayashi et al. Reference Hayashi, Fujisawa, Holland and Ohmoto1997). However, such proxies might be problematic in the Sanjiang Basin because of the mobility of some elements (e.g. Ca2+, Na+, K+ and silica) by weathering, silicification and leaching. As discussed in the previous section, our samples did not experience significant potassium metasomatism, but some samples (14JP2-2, -3, -6 and 14JP3-1, -7, -8) show evidence of recycled sediments. After ruling out these samples, the geochemical proxies indicate that the provenance was dominated by felsic and intermediate rocks, with a minor component of mafic rocks (Fig. 11a). This conclusion is consistent with the petrography and zircon morphology.

Fig. 11. (a) Discriminant function diagram of major-element provenance (Roser & Korsch, Reference Roser and Korsch1986). (b) Eu/Eu* versus Th/Sc (after McLennan et al. Reference McLennan, Taylor, McCulloch and Maynard1990). (c) Co/Th versus La/Sc (after McLennan et al. Reference McLennan, Taylor and Eriksson1983). (d) La-Th-Sc diagram for tectonic setting discrimination (after Bhatia & Crook, Reference Bhatia and Crook1986). (e) Tectonic setting of sandstone derivation from different types of provenances (after Dickinson, Reference Dickinson and Zuffa1985). (f) Cumulative proportions versus time (in Ma) of detrital zircon ages from the Sanjiang Basin (after Cawood et al. Reference Cawood, Hawkesworth and Dhuime2012). Discriminant Function 1 = (−1.773×TiO2) + (0.607×Al2O3) + (0.760×Fe2O3) + (−1.500×MgO) + (0.616×CaO) + (0.509×Na2O) + (−1.224×K2O) + (−9.090); Discriminant Function 2 = (0.445×TiO2) + (0.070×Al2O3) + (−0.250×Fe2O3) + (−1.142×MgO) + (0.438×CaO) + (1.475×Na2O) + (1.462×K2O) + (−6.861). Sample symbols as for Figure 5. The grey symbols correspond to samples from Cao et al. (Reference Cao, Guo, Shan, Ma and Sun2015) and Hu et al. (Reference Hu, Meng and Liu2021).

Some elements, such as LREE, HFSE, Co and Sc, have extremely low water–rock partition coefficients. As such, they are remarkably stable during weathering, transport and diagenesis (Chaudhuri & Cullers, Reference Chaudhuri and Cullers1979). These elements can be used as a provenance fingerprint. Diagrams of Eu/Eu* versus Th/Sc and Co/Th versus La/Sc show that the provenance areas were associated mainly with felsic rocks, without any mafic contribution (Fig. 11b, c). These results are inconsistent with our previous conclusion that a minor portion of the provenance was made of intermediate and mafic rocks. This discrepancy could be explained by the relatively weak chemical signal of mafic provenance, which means that a slight contribution from a mafic source might not be detectable in the whole-rock geochemistry of the sedimentary rock. Accordingly, the suggestion that the provenance was dominated by felsic rocks with a minor amount of intermediate and mafic rocks is not unreasonable.

The original tectonic setting of the provenance region could be inferred from the La-Th-Sc triangle plot (Fig. 11d; McLennan & Taylor, Reference McLennan and Taylor1991). According to this interpretation, samples 14JP1 and 14JP2 (from the Dongrong Formation) were derived from a continental margin (active or passive) and a continental island arc, respectively. The sandstone compositions indicate that the provenance changed from a transitional continental setting to recycled orogen (Fig. 11e). Indeed, the onset of the Paleo-Pacific plate subduction beneath the continental margin of East Asia during latest Triassic time likely resulted in a change in the source regions (Ma et al. Reference Ma, Zhu, Zhou and Qiao2017). In addition, the overall spread and proportion of detrital zircon ages indicate that the Dongrong Formation formed in a convergent plate margin (Fig. 11f; Cawood et al. Reference Cawood, Hawkesworth and Dhuime2012), which is also consistent with the tectonic evolution of Jiamusi Massif during the Triassic Period.

As demonstrated by the La-Th-Sc triangle plot (Fig. 11d), the provenance of the Yanwo Formation formed in a continental margin. The sandstone compositions indicate that the deposits were derived mainly from a recycled orogen (Fig. 11e). In contrast, detrital zircon data indicate that the Yanwo Formation formed in a collisional plate margin (Fig. 11f). The tectonic evolution of the study area was controlled by W-dipping subduction (present coordinate) since Early Jurassic time, which led to the development of a fold–thrust belt and, ultimately, to the collision between the Songnen and Jiamusi massifs. Accordingly, the formation of the Yanwo Formation could be linked to the subduction of the Paleo-Pacific Ocean and the associated accretionary orogenesis (Zhou & Li, Reference Zhou and Li2017).

5.d. Sedimentary provenance

Our sandstone petrography results are indicative of low degrees of sedimentary sorting, which likely reflect a short distance of sedimentary transport. Potential source regions could therefore be the Jiamusi Massif, Lesser Xing’an and Zhangguangcai ranges, or the Nadanhada Terrane (Fig. 1b). The geochemistry of the sedimentary sequence indicates that parts of the deposits included recycled sediments, and that first-cycle sediments were derived mainly from felsic rocks with a minor contribution from intermediate and mafic rocks. The combination of U–Pb ages and Hf data allows us to evaluate the relative contributions from the different sources.

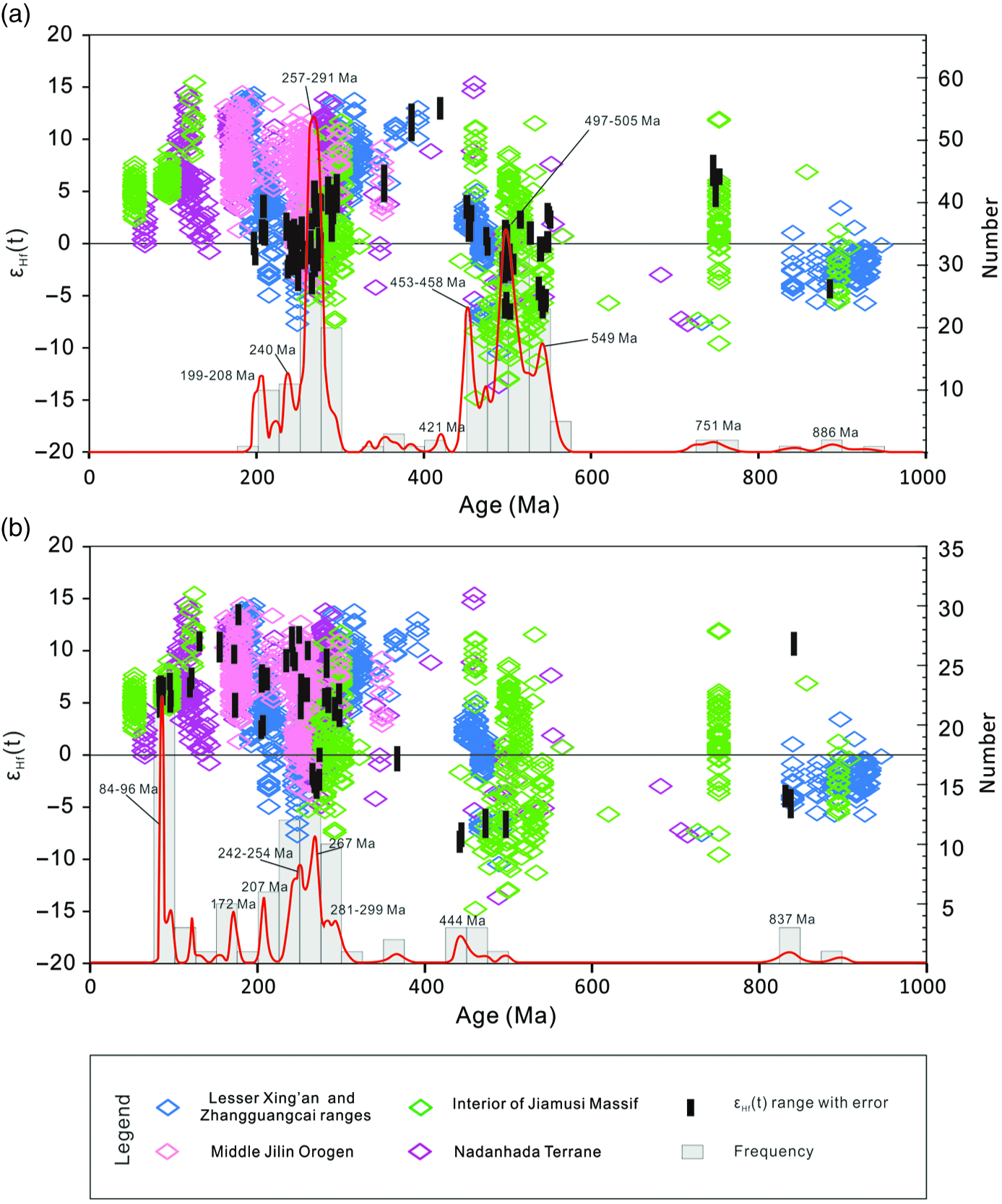

5.d.1. Provenance of the Dongrong Formation

Zircon U–Pb dating and Hf isotope data indicate that the provenance of samples 14JP1 and 14JP2 included Cambrian, Upper Ordovician, Permian and Triassic igneous rocks, with a minor component of Neoproterozoic, Devonian and Silurian rocks (Fig. 12a). Neoproterozoic and Cambrian detrital zircon grains were likely derived from the interior of the Jiamusi Massif. The minor amount of Upper Cambrian detrital zircon grains could have been derived from the Lesser Xing’an Range (Fig. 12a). Specifically, granitic gneisses and granites dated at c. 895, 751, 541 and 507–498 Ma from the Jiamusi Massif and Lesser Xing’an Range could represent the provenance terranes (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Xu, Pei, Wang and Cao2015; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Ge, Zhao, Bi, Wang, Dong and Xu2017, Reference Yang, Ge, Bi, Wang, Tian, Dong and Chen2018; Luan et al. Reference Luan, Yu, Yu, Cui and Xu2019). We note that the c. 551 Ma detrital zircon grains have similar ϵHf(t) values as inherited zircon grains from granites in the Yuejinshan Complex, which is part of the Nadanhada Terrane (Bi et al. Reference Bi, Ge, Yang, Wang, Dong, Liu and Ji2017).

Fig. 12. (a) Comparison of detrital zircon ϵHf(t) and zircon Hf isotope compositions of igneous rocks from the study area. Reference data are from Bi et al. (Reference Bi, Ge, Yang, Zhao, Yu, Zhang, Wang and Tian2014 a, b, Reference Bi, Ge, Yang, Zhao, Xu and Wang2015, Reference Bi, Ge, Yang, Wang, Xu, Yang, Xing and Chen2016, Reference Bi, Ge, Yang, Wang, Dong, Liu and Ji2017), Cao et al. (Reference Cao, Xu, Pei, Wang, Wang and Wang2013), Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Xu, Yu, Wang, Tang and Li2016, Reference Guo, Xu, Wang, Wang and Luan2018), Long et al. (Reference Long, Xu, Guo, Sun and Luan2019, Reference Long, Xu, Guo, Sun and Luan2020), Luan et al. (Reference Luan, Xu, Wang, Wang and Guo2017 b, Reference Luan, Yu, Yu, Cui and Xu2019), Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Xu, Li, Pei and Cao2009, Reference Wang, Xu, Pei, Wang and Cao2015, Reference Wang, Yang, Ge, Bi, Zhang and Xu2016 a, b, Reference Wang, Xu, Xu, Yang, Wu and Sun2017, Reference Zhang, Yan and Ji2019) and Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Ge, Zhao, Dong, Xu, Wang, Ji and Yu2015 a, b, Reference Yang, Ge, Zhao, Bi, Wang, Dong and Xu2017, Reference Yang, Ge, Bi, Wang, Tian, Dong and Chen2018).

The source region of the Ordovician (c. 477 and 458–453 Ma) detrital zircon grains could be associated with the Lesser Xing’an and Zhangguangcai ranges (Fig. 12a). Granitoids from the Lesser Xing’an Range, dated c. 476 Ma and c. 457 Ma, likely provided detritus to the Sanjiang Basin (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Xu, Pei, Wang and Guo2016 b). Silurian–Carboniferous detrital zircon grains were also likely derived from the Lesser Xing’an and Zhangguangcai ranges, with a minor contribution from the Middle Jilin Orogen (Fig. 12a). Indeed, zircon grains found in a Devonian (366 ± 5 Ma) granite from the Lesser Xing’an range are characterized by similar ϵHf(t) values as those found in detrital zircon grains from the Dongrong Formation (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Xu, Wang, Wang and Luan2018). In addition, 364–340 Ma rhyolites and granites from the Middle Jilin Orogen might have contributed to the detrital sediments (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Xu, Pei, Wang and Cao2015).

The main source rocks of the Dongrong Formation were Permian (291–257 Ma) and Early Triassic (c. 240 Ma) in age, which could be associated with four potential source regions (Fig. 12a): (1) 300–261 Ma granitoids from the Jiamusi Massif (Yu et al. Reference Yu, Wang, Xu, Gao and Tang2013; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Ge, Zhao, Yu and Zhang2015 b; Bi et al. Reference Bi, Ge, Yang, Wang, Xu, Yang, Xing and Chen2016; Dong et al. Reference Dong, Ge, Yang, Bi, Wang and Xu2017 a, b; Long et al. Reference Long, Xu, Guo, Sun and Luan2020); (2) 293–257 Ma rhyolites, andesites and gabbros, and 245 Ma granitoids from the Lesser Xing’an and Zhangguangcai ranges (Long et al. Reference Long, Xu, Guo, Sun and Luan2019, Reference Long, Xu, Guo, Sun and Luan2020); (3) 263–256 Ma ganitoids, monzonites and gabbros, and c. 244 Ma monzonites and granites from the Middle Jilin Orogen (Cao et al. Reference Cao, Xu, Pei, Wang, Wang and Wang2013; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Xu, Pei, Wang and Cao2015); and (4) 288–269 Ma granitoids and gabbros from the Nadanhada Terrane (Bi et al. Reference Bi, Ge, Yang, Zhao, Yu, Zhang, Wang and Tian2014 a, Reference Bi, Ge, Yang, Zhao, Xu and Wang2015; Sun et al. Reference Sun, Xu, Wilde and Chen2015). Hf compositions of Upper Triassic detrital zircon grains are similar to those found in c. 210 Ma granites and gabbros from the Lesser Xing’an and Zhangguangcai ranges, indicating that the sediments were likely derived from these granites (Long et al. Reference Long, Xu, Guo, Sun and Luan2020).

5.d.2. Provenance of the Yanwo Formation

The provenance of the Yanwo Formation is associated mainly with upper Permian, Lower Triassic, Middle Jurassic and Upper Cretaceous rocks, with a minor contribution of Neoproterozoic, Ordovician and lower Permian rocks (Fig. 12b). Neoproterozoic detrital zircon grains are characterized by two groups with distinct Hf compositions. The first group of detrital zircon grains (837–831 Ma) were possibly derived from c. 840 Ma gneissic granodiorites from the Lesser Xing’an Range (Luan et al. Reference Luan, Xu, Wang, Wang and Guo2017 b). The origin of the second group (c. 841 Ma zircon grains with ϵHf(t) values of 10.7 ± 0.9) remains unclear. Cambrian and Lower Ordovician detrital zircon grains were possibly derived from granitoids in the Lesser Xing’an Range and the Jiamusi Massif (Fig. 12b). The 444 ± 5 Ma detrital zircons have similar Hf compositions as those from the 450 ± 2 Ma granites in the Lesser Xing’an Range (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Xu, Pei, Wang and Cao2015). The 367 ± 11 Ma zircons have similar Hf composition as inherited zircons from the 267 ± 5 Ma rhyolite in the Yuejinshang Complex (Bi et al. Reference Bi, Ge, Yang, Wang, Dong, Liu and Ji2017). Consequently, these granites and rhyolites likely contributed to the sediments of the Yanwo Formation.

Permian and Triassic zircon grains from the Yanwo Formation have similar Hf compositions to those from the Dongrong Formation (Fig. 12b), suggesting that their provenances were similar. The Hf compositions of Jurassic detrital zircons indicate that their provenance was associated with the Middle Jilin Orogen, Nadanhada Terrane and the Zhangguangcai Range. The source rocks might include 175–172 Ma and 164 Ma granitoids and diorites from the Middle Jilin Orogen, c. 174 and 167 Ma rhyolites, andesites and basalts from the Nadanhada Terrane (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Xu, Pei, Wang and Cao2015, Reference Wang, Xu, Xu, Yang, Wu and Sun2017), and c. 177 Ma granitoids from the Zhangguangcai Range (Long et al. Reference Long, Xu, Guo, Sun and Luan2020). The Hf compositions of Cretaceous detrital zircon grains are similar to these from Nadahada Terrane and the Jiamusi Massif (Fig. 12b). Granitoids from the interior of the Jiamusi Massif, dated at c. 117 and 95–89 Ma (Yu et al. Reference Yu, Wang, Xu, Gao and Tang2013), and granitoids from Nadanhada Terrane (c. 133 and 120 Ma), might have contributed to the sediments of the Yanwo Formation (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Xu, Xu, Yang, Wu and Sun2017).

In summary, the evidence suggests that the sediments of the Sanjiang Basin were derived mainly from the Jiamusi Massif and the surrounding orogens and terranes. Source rocks were dominated by felsic rocks with a minor amount of intermediate and mafic rocks.

5.e. Mesozoic uplift history of the northeastern Asian continental margin

During the Mesozoic Era, the northeastern Asian continental margin was an active continental margin, characterized by a fore-arc region, island arc and retro-arc foreland basin systems (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Yan and Ji2019). Subduction processes were likely responsible for uplift and exhumation of the continental margin, thus controlling drainage systems and the architecture of sedimentary basins (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Chen, Batt, Dilek, Na, Sun, Yang, Meng and Zhao2015; Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, István, Liu, Li and Eynatten2020). Many previous studies have investigated surface processes of the northeastern Asian continental margin using information associated with the distribution of magmatism (e.g. Wu et al. Reference Wu, Sun, Ge, Zhang, Grant, Wilde and Jahn2011; Cao et al. Reference Cao, Xu, Pei, Wang, Wang and Wang2013; Song et al. Reference Song, Stepashko and Ren2015; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Xu, Xing, Wang, Zhang, Wu, Sun and Ge2019), contractional structures (e.g. Zhou & Li, Reference Zhou and Li2017; Zheng et al. Reference Zheng, Sun, Wan, Wang, He and Zhang2019) and unconformities within the stratigraphic succession (e.g. Deng et al. Reference Deng, He, Pan and Zhu2013; Song et al. Reference Song, Ren, Stepashko and Li2014). The integrated evidence from the Sanjiang Basin, based on stratigraphic data, provenance studies and seismic reflection profiles (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Dilek, Chen, Yang and Meng2017), provides new insights into the uplift history and associated subduction processes.

Crustal-scale shortening and uplift are generally expressed by the presence of changes in provenance, unconformities, positive flower structures, imbricate thrusts and folds (Fig. 2). The presence of a Jurassic unconformity indicates that the study area might have experienced one stage of surface uplift. The Jurassic provenance changes of basinal strata from Lesser Xing’an and Zhangguangcai ranges to Nadanhada Terrane and Middle Jilin Orogen, and the Jurassic detrital zircons of Yanwo Formation, were mainly derived from the Nadanhada Terrane in the eastern of the Sanjiang Basin. The provenance change appears to correspond to surface uplift in the eastern part of the Sanjiang Basin. Based on geochronological and geochemical studies, it has been suggested that the tectonic evolution of the northeastern Asian continental margin was controlled by W-wards subduction (present coordinate) of the Paleo-Pacific Ocean during the Early Jurassic Epoch (190–159 Ma; Wu et al. Reference Wu, Sun, Ge, Zhang, Grant, Wilde and Jahn2011; Xu et al. Reference Xu, Pei, Wang, Meng, Ji, Yang and Wang2013). We propose that the uplift of the continental margin resulted from the initiation of this W-wards subduction.

Positive flower structures and imbricate thrusts are recognized in Lower Cretaceous strata (cross-section A–B; Fig. 2), and folds and imbricate thrusts occur in Upper Cretaceous strata (cross-section C-D; Fig. 2). These contractional structures are consistent with the two major unconformities within the Cretaceous strata (Fig. 2), suggesting that the study area experienced at least two stages of contractional deformation and uplift during the Cretaceous Period. The Cretaceous unconformity in the Sanjiang Basin seems to be expressed by the absence of detrital zircon ages dated 117–144, 133–146 and 115–145 Ma in the Lower Cretaceous Didao, Chengzihe and Muling formations, respectively (Fig. 13). In comparison, the Upper Cretaceous Hailang and Yanwo formations lack zircon grains dated at 97–144, 99–120 and 131–149 Ma (Fig. 13), respectively. According to the geochronological compatibility and the two major unconformities, we conclude that the northeastern Asian continental margin experienced at least two stages of uplift during the Cretaceous Period (i.e. 144–133 and 120–99 Ma).

Fig. 13. Comparison of probability diagrams of detrital zircon ages for sedimentary sequences from the Sanjiang Basin. Reference data for the Didao, Chengzihe, Muling and Hailang formations from Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Chen, Batt, Dilek, Na, Sun, Yang, Meng and Zhao2015).

During latest Jurassic – Early Cretaceous time, the Izanagi Plate (Paleo-Pacific Ocean) underwent a 24° clockwise rotation (Seton et al. Reference Seton, Müller, Zahirovic, Gaina, Torsvik, Shephard, Talsma, Gurnis, Turner, Maus and Chandler2012). This change in the plate motion could have generated shear stresses along the continental margin, which might have led to the uplift during 144–133 Ma (Fig. 14b). Subsequently, during the latest Early Cretaceous Epoch, the subduction dip angle of the Paleo-Pacific slab was reduced (Sun et al. Reference Sun, Chen, Milan, Wilde, Jourdan and Xu2018), enhancing compressional deformation and further surface uplift (Fig. 14c). The two stages of uplift were likely responsible for the formation of the unconformity in the Cretaceous strata and the development of contractional structures (positive flower structures and imbricate thrusts). In conclusion, the northeastern Asian continental margin experienced at least three stages of uplift, possibly driven by subduction initiation (Early Jurassic) and the changes in the plate kinematics (Early and Late Cretaceous).

Fig. 14. Schematic illustration of the Early Jurassic and Cretaceous uplift events in the northeastern Asian continental margin.

6. Conclusions

Based on sandstone petrography, geochemistry of sedimentary rocks, U–Pb ages and Hf isotope of detrital zircons, the following conclusions are drawn.

1. The Dongrong Formation was deposited after 208–201 Ma. Deposition of the Yanwo Formation occurred after 85 Ma and before 54 Ma.

2. The two basinal strata were subjected to weathering processes that progressively intensified during the deposition of these formations. The rocks experienced low degrees of sedimentary sorting, silicification and insignificant potassium metasomatism. Some of the mudstones contain recycled sediments.

3. The provenance of the Dongrong and Yanwo formations was likely associated with the Jiamusi Massif and surrounding orogens and terranes. The source rocks were dominated by felsic rocks with a minor component of mafic rocks.

4. The northeastern Asian continental margin experienced at least three stages of uplift. The first uplift phase was possibly driven by the initiation of subduction of the Paleo-Pacific Ocean during Early Jurassic time, whereas the second and third phases are interpreted to be associated with a change in plate kinematics during Early Cretaceous time.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editor Stephen Hubbard and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive suggestions and comments. We are grateful to staff of the Wuhan Samplesolution Analytical Technology Co., Ltd. and the State Key Laboratory of Geological Processes and Mineral Resources, China University of Geosciences, for their advice and assistance during zircon LA-ICP-MS U–Pb dating, major- and trace-element analyses, and Hf isotope analyses. This work was financially supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (N2123029) and the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (D2020501002). All data are archived at Mendeley Date (https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/nfy7gxg38p/1).

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756821000996