1. Introduction

The Palaeoproterozoic Birimian Terrane of the West African Craton (WAC) continues to engage the attention of geoscientists, and has witnessed a surge in research activities to unravel the geological history of the terrane and its broader implications on the WAC. The present-day Earth has reached near-equilibrium between the amount of crust being generated and that being returned to the mantle at subduction zones. Since the Neoarchean Era, there has been no net loss of crustal material of the continental crust. A myriad of evidence supports secular change in crustal processes through time, including magma compositions, mantle temperatures and metamorphic gradients (Spencer et al. Reference Spencer, Roberts and Santosh2017). A study conducted by Ganne et al. (Reference Ganne, de Andrade, Weinberg, Vidal, Dubacq, Kagambega, Naba, Baratoux, Jessell and Allibon2012) in the Fada N’Gourma region of the WAC in Burkina Faso concluded that modern-style plate tectonics existed during Palaeoproterozoic time. The Paleoproterozoic Era (2.5–1.6 Ga) represents the main episode of crustal growth recorded on present-day continents (Giustina et al. Reference Giustina, de Oliveira, Pimentel, de Melo, Fuck, Dantas and Buhn2009) and was characterized by widespread mafic magmatism across previously stabilized Archean crustal domains (e.g. Heaman, Reference Heaman1997; Isley & Abbott, Reference Isley and Abbott1999). This global event was related to the assembly of the supercontinent Columbia during Palaeoproterozoic time (e.g. Rogers & Santosh Reference Rogers and Santosh2002, Reference Rogers and Santosh2009; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Cawood, Wilde and Sun2002, Reference Zhao, Sun, Wilde and Li2004; Meert, Reference Meert2012). It is therefore suggested that the early orogenic systems formed through subduction–accretionary processes during the Eburnean Orogeny partly created the supercontinent Columbia.

The Palaeoproterozoic Birimian Terrane of Ghana occupies the southeastern portion of the WAC, and this area has been subject to much research (e.g. Abouchami et al. Reference Abouchami, Boher, Michard and Albarede1990; Eisenlohr & Hirdes, Reference Eisenlohr and Hirdes1992; Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Moorbath, Leube and Hirdes1992; Davis et al. Reference Davis, Hirdes, Schaltergger and Nunoo1994; Anum et al. Reference Anum, Sakyi, Su, Nude, Nyame, Asiedu and Kwayisi2015; Block et al. Reference Block, Ganne, Baratoux, Zeh, Parra-Avila, Jessell, Aillères and Siebenaller2015), all aimed at contributing to the better understanding of the geodynamic evolution of the WAC. However, the geochronology, petrogenesis, provenance and tectonic setting of the Palaeoproterozoic Birimian rocks remain the focus of continuous discussion. The tectonic settings proposed by some of the studies so far range from the generation of the Birimian juvenile crust in arc environments (e.g. Sylvester & Attoh, Reference Sylvester and Attoh1992; Asiedu et al. Reference Asiedu, Dampare, Sakyi, Banoeng-Yakubo, Osae, Nyarko and Manu2004; Dampare et al. Reference Dampare, Shibata, Asiedu and Osae2005; Sakyi et al. Reference Sakyi, Su, Anum, Kwayisi, Dampare, Anani and Nude2014, Reference Sakyi, Anum, Su, Nude, Asiedu, Nyame, Kwayisi and Su2018a, b) to plume-related magmatism (e.g. Abouchami et al. Reference Abouchami, Boher, Michard and Albarede1990; Lompo, Reference Lompo, Reddy, Mazumder, Evans and Collins2009). Further, two major models have been proposed to explain the tectonic processes involved in the formation of the Birimian rocks. These are accretionary orogeny (e.g. Abouchami et al. Reference Abouchami, Boher, Michard and Albarede1990; Davis et al. Reference Davis, Hirdes, Schaltergger and Nunoo1994; Feybesse & Milési, Reference Feybesse and Milési1994; Hirdes et al. Reference Hirdes, Davis, Ludtke and Konan1996; Hirdes & Davis, Reference Hirdes and Davis2002) and transcurrent tectonics models (e.g. Doumbia et al. Reference Doumbia, Pouclet, Kouamelan, Peucat, Vidal and Delor1998).

In the past, geological studies on the Birimian Terrane of Ghana have focused on either the metavolcanic rocks (e.g. Dampare et al. Reference Dampare, Shibata, Asiedu, Osae and Banoeng-Yakubo2008, Reference Dampare, Shibata, Asiedu, Osamu, Manu and Sakyi2009; Senyah et al. Reference Senyah, Dampare and Asiedu2016), metasedimentary rocks (e.g. Asiedu et al. Reference Asiedu, Asong, Atta-Peters, Sakyi, Su, Dampare and Anani2017) or the granitoids (e.g. Losiak et al. Reference Losiak, Schulz, Buchwaldt and Koeberl2013; Anum et al. Reference Anum, Sakyi, Su, Nude, Nyame, Asiedu and Kwayisi2015; Petersson et al. Reference Petersson, Scherstén, Kemp, Kristinsdóttir, Kalvig and Anum2016) mostly in southern Ghana.

The northwestern part of Ghana has recently witnessed a couple of studies, all aimed at understanding the geological evolution of the Palaeoproterozoic Birimian Terrane (e.g. de Kock et al. Reference de Kock, Armstrong, Siegfried and Thomas2011; Amponsah et al. Reference Amponsah, Salvi, Béziat, Siebenaller and Jessell2015, Reference Amponsah, Salvi, Béziat, Baratoux, Siebenaller, Nude, Nyarko and Jessell2016b; Block et al. Reference Block, Ganne, Baratoux, Zeh, Parra-Avila, Jessell, Aillères and Siebenaller2015, Reference Block, Baratoux, Zeh, Laurent, Bruguier, Jessell, Aillères, Sagna, Parra-Avila and Bosch2016a, b). With the advent of new and improved analytical techniques, most of the studies on the Birimian Terrane in Ghana in the past decade were often limited to individual belts and basins or adjacent belts and basins (e.g. Dampare et al. Reference Dampare, Shibata, Asiedu, Osae and Banoeng-Yakubo2008, Reference Dampare, Shibata, Asiedu, Osamu, Manu and Sakyi2009; Anum et al. Reference Anum, Sakyi, Su, Nude, Nyame, Asiedu and Kwayisi2015; Abitty et al. Reference Abitty, Dampare, Nude and Asiedu2016; Senyah et al. Reference Senyah, Dampare and Asiedu2016). The aim is to improve on previous works in terms of sample density, and also take advantage of improved analytical techniques to deepen our understanding of the evolution of the Palaeoproterozoic Birimian rocks of the WAC. These studies include a comprehensive zircon U–Pb dating of the granitoids in the Lawra Belt by Sakyi et al. (Reference Sakyi, Su, Anum, Kwayisi, Dampare, Anani and Nude2014) that produced the oldest-published ages of 2211 Ma and 2213 Ma. The study suggested that the emplacement of Birimian granitoids in Ghana may have commenced much earlier than previously reported in the literature. Block et al. (Reference Block, Ganne, Baratoux, Zeh, Parra-Avila, Jessell, Aillères and Siebenaller2015) carried out petrological and geochronological studies of high-grade ortho- and paragneisses of the eastern Baoulé-Mossi domain, covering an extensive area in northern Ghana, and revealed the exhumation of the lower crust along reverse, normal and transcurrent shear zones and juxtaposed against shallow crustal slices during the Eburnean Orogeny. The study of granitoids in the middle to northern parts of Ghana, notably the Bole-Bulenga and Abulembire domains, revealed that the former is commonly migmatitic whereas the latter is principally made of paragneisses, sometimes migmatitic, intruded by granitoid gneisses emplaced during c. 2200–2125 Ma (Agyei Duodu et al. Reference Agyei Duodu, Loh, Boamah, Baba, Hirdes, Toloczyki and Davis2009; de Kock et al. Reference de Kock, Theveniaut, Botha and Gyapong2009). Block et al. (Reference Block, Baratoux, Zeh, Laurent, Bruguier, Jessell, Aillères, Sagna, Parra-Avila and Bosch2016a) showed that all the different rock types that make up the Palaeoproterozoic crust of northern Ghana were formed together over a prolonged period of c. 100 Ma during c. 2.21–2.11 Ga, where the tonalite–trondhjemite–granodiorites (TTGs) were derived from the reworking of low-K hydrous mafic crust. The more-felsic rock types were formed by reworking of older felsic crustal rocks. It was further revealed that most of the Palaeoproterozoic Birimian rocks in the Bole–Nangodi Belt do not show any significant variation in geochemical characteristics, suggesting that they may be products of a similar source with varying degrees of evolution and generated in similar tectonic settings (e.g. Block et al. Reference Block, Baratoux, Zeh, Laurent, Bruguier, Jessell, Aillères, Sagna, Parra-Avila and Bosch2016a).

U–Pb and Hf-isotope studies of detrital zircons from the Palaeoproterozoic Baoulé–Mossi domain (Parra-Avila et al. Reference Parra-Avila, Belousova, Fiorentini, Baratoux, Davis, Miller and McCuaig2016) indicate that, although the zircons generally confirm its juvenile origin, they also indicate reworking of an older crust at a much larger scale than previously recognized. The identification of Archean zircons in the region therefore argues for greater interaction between the Baoulé–Mossi domain and the Archean Kénéma–Man domain. Additionally, zircon U–Pb dating and Hf and O-isotope studies of igneous rocks from the Palaeoproterozoic Baoulé-Mossi domain of the WAC, covering Burkina Faso, Ghana, Guinea and Mali, revealed the juvenile isotopic character of the domain, and further showed that the southern part of the WAC evolved by accretionary processes (Parra-Avila et al. Reference Parra-Avila, Kemp, Fiorentini, Belousova, Baratoux, Block, Jessell, Bruguier, Begg, Miller, Davis and McCuaig2017, Reference Parra-Avila, Belousova, Fiorentini, Eglinger, Block and Miller2018). Similar to the above, zircon U–Pb age and Lu–Hf isotopic data from granites of southern, southeastern and northwestern Ghana suggest juvenile crustal addition with a short period of reworking of Archaean crust within the Palaeoproterozoic Birimian Terrane of Ghana, and provides evidence of subduction-related crustal growth (Petersson et al. Reference Petersson, Scherstén, Kemp, Kristinsdóttir, Kalvig and Anum2016, Reference Petersson, Scherstén and Gerdes2018). Grenholm et al. (Reference Grenholm, Jessell and Thebaud2019) also showed that the Birimian Orogen in the southern WAC forms part of a large accretionary–collisional orogenic system that extends into the Reguibat shields in northern WAC and southwards into equivalent crust in the Amazon Craton. They indicated that early evolution of the orogen was characterized by deposition of volcanic–volcanosedimentary successions and emplacement of limited intrusives, with a significant contribution from juvenile sources. It was further concluded that the alternation between compression and extension within the context of regional convergence was a key factor in driving the evolution of the Birimian Orogen and establishing the architecture of the crust exposed in the southern WAC. The presence of enclaves of different compositions, most of which are mafic, is characteristic of the Palaeoproterozoic granitoid intrusions of the Birimian in Ghana. Enclaves within igneous rocks can potentially provide information on the origin and/or evolution of the magma in which they are found. However, they have received little or no attention in the various studies so far carried out in the Birimian terrane of the WAC.

In this paper, we present whole-rock geochemistry and Rb–Sr and Sm–Nd isotopic systematics of mafic to intermediate metavolcanic rocks and granitoid-hosted mafic enclaves from the Lawra Volcanic Belt of the Palaeoproterozoic Terrane of the WAC in Ghana. The study aims to provide further insights and a deeper understanding of the origin, petrogenesis and tectonic emplacement of the volcanic rocks and the enclaves, with the ultimate goal of contributing towards a better understanding of the geodynamic evolution of the WAC.

2. Geological setting

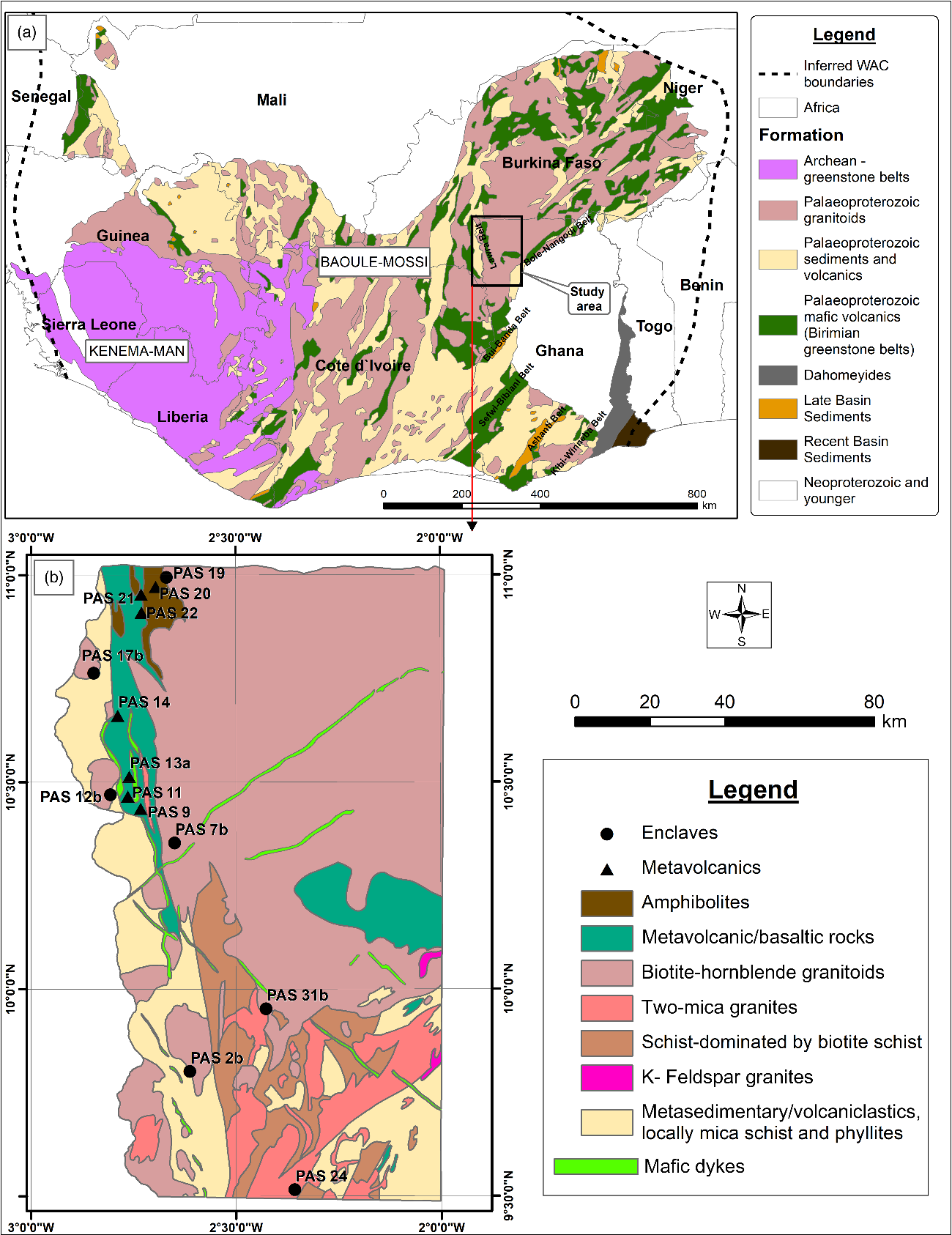

The Palaeoproterozoic Birimian Terrane of Ghana occupies the southeastern part of the WAC (Fig. 1a). The Lawra Volcanic Belt is located in northwestern Ghana (Fig. 1a, b) and represents one out of the six Birimian Volcanic belts in Ghana; the remaining five are the Kibi–Winneba, Ashanti, Sefwi, Bui and Bole–Nangodi belts (e.g. Leube et al. Reference Leube, Hirdes, Mauer and Kesse1990). These volcanic belts are separated by intervening NE-trending sedimentary basins, namely the Cape Coast, Kumasi, Sunyani and Maluwe basins (Kesse, Reference Kesse1985). A conspicuous feature of the Birimian terrane of Ghana is the NE–SW trend of all the volcanic belts except for the Lawra Belt, which trends nearly N–S (Leube et al. Reference Leube, Hirdes, Mauer and Kesse1990; Hirdes et al. Reference Hirdes, Davis and Eisenlohr1992). The Lawra Belt marks the southern side of the Proterozoic Boromo greenstone belt that extends through southern and central Burkina Faso (Béziat et al. Reference Béziat, Bourges, Debat, Lompo, Martin and Tollon2000; Baratoux et al. Reference Baratoux, Metelka, Naba, Jessell, Gregoire and Ganne2011). On the other hand, the basins contain metasedimentary rocks comprising dacitic volcaniclastics, wackes and argillites, as well as granitoids, occurring in varying proportions (Leube et al. Reference Leube, Hirdes, Mauer and Kesse1990).

Fig. 1. (a) Geological sketch map of the Man Shield showing the WAC and Palaeoproterozoic Birimian rocks. The location of the study area in northwestern Ghana and the various volcanic belts are also shown. (b) Geological sketch map of the Lawra Volcanic Belt, showing the distribution of the various rock units. Sample positions are also indicated. Modified after Agyei Duodu et al. (Reference Agyei Duodu, Loh, Boamah, Baba, Hirdes, Toloczyki and Davis2009).

The Lawra Volcanic Belt (Fig. 1b) is made up of metamorphosed volcanic rocks comprising mainly tholeiitic subalkaline meta-basalts, meta-andesites, porphyritic calc-alkaline hornblende-actinolite-schists and amphibolites (e.g. Jessell et al. Reference Jessell, Amponsah, Baratoux, Asiedu, Loh and Ganne2012; Amponsah et al. Reference Amponsah, Salvi, Béziat, Baratoux, Siebenaller, Jessell, Nude and Gyawu2016a). The metasedimentary rocks in the belts are detrital volcanogenic sediments, comprising mainly volcaniclastics, volcaniclastic wackes, argillites and tuffs that have been metamorphosed to schists, phyllites and greywackes (e.g. Leube et al. Reference Leube, Hirdes, Mauer and Kesse1990). Occurring in the transition zones between the volcanic belts and sedimentary basins are different types of chemical sediments (e.g. cherts, gondites and sulphide- and carbonate-bearing rocks), pyroclastic-volcaniclastic and volcanic rocks (e.g. Leube et al. Reference Leube, Hirdes, Mauer and Kesse1990). The volcano-sedimentary terranes are intruded by granitoids of various ages, but two main suites are recognized; the Dixcove-type granitoids intrude the Birimian volcanic rocks and are interpreted to be coeval with them (Eisenlohr & Hirdes, Reference Eisenlohr and Hirdes1992). They are metaluminous and comprise hornblende- to biotite-bearing granodiorites to diorites, monzonites and syenites. In contrast, the Cape Coast-type granitoids intrude the Birimian sedimentary rocks and are mainly peraluminous, two-mica granodiorites, with lesser hornblende- and biotite-bearing granodiorites (Eisenlohr & Hirdes, Reference Eisenlohr and Hirdes1992). These granitoids are interpreted to have been emplaced synchronously with the major deformation event that affected the rocks of the Birimian Supergroup (Eisenlohr & Hirdes, Reference Eisenlohr and Hirdes1992).

3. Materials and methods

Samples for this study are seven mafic to intermediate metavolcanic rocks and seven granitoid-hosted enclaves from the Lawra Belt. Because of the weathered nature of the metavolcanic rocks, and the fact that sampling was restricted to the surface, our sampling protocol focused mainly on road-cuts where fresh samples were exposed; this is the main reason for the limited number of metavolcanic samples used for the study.

3.a. Major and trace elements

Major- and trace-element abundances in the 14 samples were measured at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IGGCAS) in Beijing. Chips of whole-rock samples free from any weathered surface were crushed and ground in an agate mill to c. 200 mesh (74 μm). For major-element analysis, approximately 0.5 g of the rock powder was mixed with 5 g of Li2B4O7 and three drops of NH4Br, and the mixture was fused in a furnace to form a glass disk. Major elements were determined on fused glass beads using Shimadzu X-ray fluorescence (XRF-1500), operating with a current of 50 mA and voltage of 50 kV. A detailed description of the analytical procedures is reported in Chu et al. (Reference Chu, Wu, Walker, Rudnick, Pitcher, Puchtel, Yang and Wilde2009).

Trace elements were determined by inductively coupled plasma – mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) using an Agilent 7500a system. The analyses were carried out following the procedures described in Chu et al. (Reference Chu, Wu, Walker, Rudnick, Pitcher, Puchtel, Yang and Wilde2009). Analytical precisions were generally better than 5%, while analytical uncertainties were 1–3% for elements present in concentrations of >1 wt% and about 10% for elements present in concentrations of <1 wt%.

3.b. Rb–Sr and Sm–Nd isotopes

Six metavolcanic and three enclave samples were analysed for Rb–Sr and Sm–Nd isotopes using a VG-354 thermal ionization magnetic sector mass spectrometer at the State Key Laboratory of Lithospheric Evolution, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing. The procedures followed for chemical separation and isotopic analyses are described in Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Sun, Lu, Zhou, Zhou, Liu and Zhang2001). Procedural blanks were <100 pg for Rb, 200 pg for Sr, <20 pg for Sm and <50 pg for Nd. Measured 87Sr/86Sr and 143Nd/144Nd ratios were corrected for mass-fractionation using 86Sr/88Sr = 0.1194 and 146Nd/144Nd = 0.7219, respectively. During the period of data collection, the measured values for the NBS987-Sr and JNdi-Nd standards were 87Sr/86Sr = 0.710245 ± 20 (n = 10) and 143Nd/144Nd = 0.512125 ± 15 (n = 8). Uncertainties for Rb/Sr and Sm/Nd ratios were <2% and <0.5%, respectively.

4. Results

4.a. Field observations and petrography

Metavolcanic rocks in the Lawra Belt occur in restricted locations, and commonly occur as disconnected outcrops or isolated hills; in some cases, they display extensive exposure. For example, in the vicinity of the Yagha community, located about 18 km NW of Nadowli, the exposed meta-basalts are up to c. 850 m long but have experienced extensive surface weathering. In other locations, the disconnected outcrops are sub-rounded at the base with dimensions ranging from c. 80 m by 60 m to c. 100 m by 80 m. A few relatively small outcrops measuring up to 50 m in diameter at the base also occur in the area. The granitoid intrusions occur in close proximity to the metavolcanic rocks. They are generally less deformed compared with the metavolcanic rocks and contain oriented enclaves with mafic to intermediate compositions. In some areas, the orientation of the enclaves is subparallel to the metamorphosed volcanic rocks. However, a few sizeable rocks are less ellipsoidal and are characterized by curved boundaries. Because of the altered nature of the metavolcanic rocks, sampling on the surface was avoided. Instead, we relied on exposures in road-cuts, notably newly constructed feeder roads where relatively fresh surfaces were exposed. Although the field relations indicate that the metavolcanic rocks are intruded by belt-type granitoids, individual suites of metavolcanic rocks are generally devoid of cross-cutting igneous bodies. Rather, the granitoid intrusions are characterized by criss-crossing quartz veins and dykes of other igneous rocks.

4.a.1. Metavolcanic rocks

The metavolcanic rocks consist of mainly metamorphosed basalts and basaltic andesites, with minor andesites and amphibolites. The metavolcanic rocks have generally experienced greenschist facies metamorphism (Abouchami et al. Reference Abouchami, Boher, Michard and Albarede1990; Amponsah et al. Reference Amponsah, Salvi, Béziat, Baratoux, Siebenaller, Jessell, Nude and Gyawu2016a) and various degrees of alteration; these have subsequently overprinted the primary minerals with preserved pseudomorphs (Fig. 2a), evident from the presence of secondary minerals such as actinolite, epidote, sericite and chlorite. The metabasalts (Fig. 2a–c) are fine-grained and dark green to dark grey. They are massive or weakly foliated, aphyric and sparsely porphyritic, with less than 10% phenocrysts set in a microcrystalline groundmass composed of plagioclase, secondary quartz and calcite that occur as either interstitial or impregnation. The primary minerals of the metabasalts (Fig. 3a) are mainly plagioclase (50–55%) and clinopyroxene (40–42%) that are either partially or completely replaced by actinolite and epidote. The plagioclase occurs as euhedral to subhedral phenocrysts, which are replaced partially or completely by epidote, actinolite and sericite, and to a lesser extent by albite and calcite. In some samples, relict clinopyroxene and plagioclase occur as subhedral to anhedral grains. Accessory minerals are apatite, magnetite and ilmenite.

Fig. 2. Field outcrop photographs from the Lawra Volcanic Belt: (a) meta-basalt with preserved pillow structures near Jirapa; (b) an outcrop of meta-basalt (PAS 14) near Lawra; (c) hand specimen of basalt (PAS 13a) sampled from outcrop in Figure 3a; (d) mafic enclave (PAS 2b) in hornblende granodiorite (PAS 2a) near Wechiau; and (e) mafic enclave (PAS 31b) in gneissic biotite granite (PAS 31a), near Wa.

Fig. 3. Photomicrographs (crossed nicols) of the metavolcanic rocks and enclaves: (a) meta-andesite (Lawra); (b) meta-basalt (Lawra); (c) diorite enclave; (d) gabbro enclave. Cpx – clinopyroxene; Opx – orthopyroxene; Ser – sericite; Qtz – quartz; Opq – opaque; Chl – chlorite; Ep – epidote; Plg – plagioclase.

The meta-andesites are greenish to dark grey, fine- to medium-grained, and massive to weakly foliated. They are porphyritic with plagioclase constituting the major phenocryst phase. As a result of metamorphism and alteration, some of the phenocrysts have been replaced by actinolite, chlorite and epidote. For example, euhedral to subhedral plagioclase crystals are commonly replaced by epidote. The fine-grained groundmass is principally composed of plagioclase, and secondary actinolite, epidote and quartz. Apatite and opaque minerals occur as accessory minerals.

The amphibolite (PAS 20) is fine-grained, dark grey to green, and characterized by well-developed foliation. It is composed predominantly of hornblende and plagioclase with minor quartz. The fine-grained nature of the amphibolite suggests that its protolith was most likely to be basalt.

4.a.2. Granitoid-hosted enclaves

The enclaves are hosted mainly in hornblende granodiorite and gneissic biotite granite (detailed description in Sakyi et al. Reference Sakyi, Su, Anum, Kwayisi, Dampare, Anani and Nude2014), and are predominantly mafic in composition, made up of mainly diorites and gabbros. The only exceptions are samples PAS 7b and PAS 24, which are andesitic in composition. Some of the enclaves are either ellipsoidal or ovoid in shape and tend to have sharp contacts with the enclosing host rock (Fig. 2d, e). The diorite enclaves (Figs 2d, 3c) are dark grey, coarse-grained and weakly foliated, and are dominantly composed of plagioclase (25–20%), clinopyroxene and orthopyroxene (35–30%), hornblende (35–30%) with minor biotite (5%) and quartz (<5%). The plagioclase displays some degree of alteration, mostly in the core. The clinopyroxene is euhedral and occurs in elongated form and shows considerable degree of alteration. The biotite is tabular to bladed, while the hornblende is subhedral and sometimes altered to epidote. The gabbros (Figs 2e, 3d) are dark, medium- to coarse-grained and massive, and are principally composed of calcic plagioclase feldspar (60%) and clinopyroxene (35%) that are altered to sericite and chlorite, and epidote, respectively, but retain preserved pseudomorphs. Also present are chlorites (5%) and interstitial quartz, which shows undulose extinction.

4.b. Major- and trace-element geochemistry

4.b.1. Metavolcanic rocks

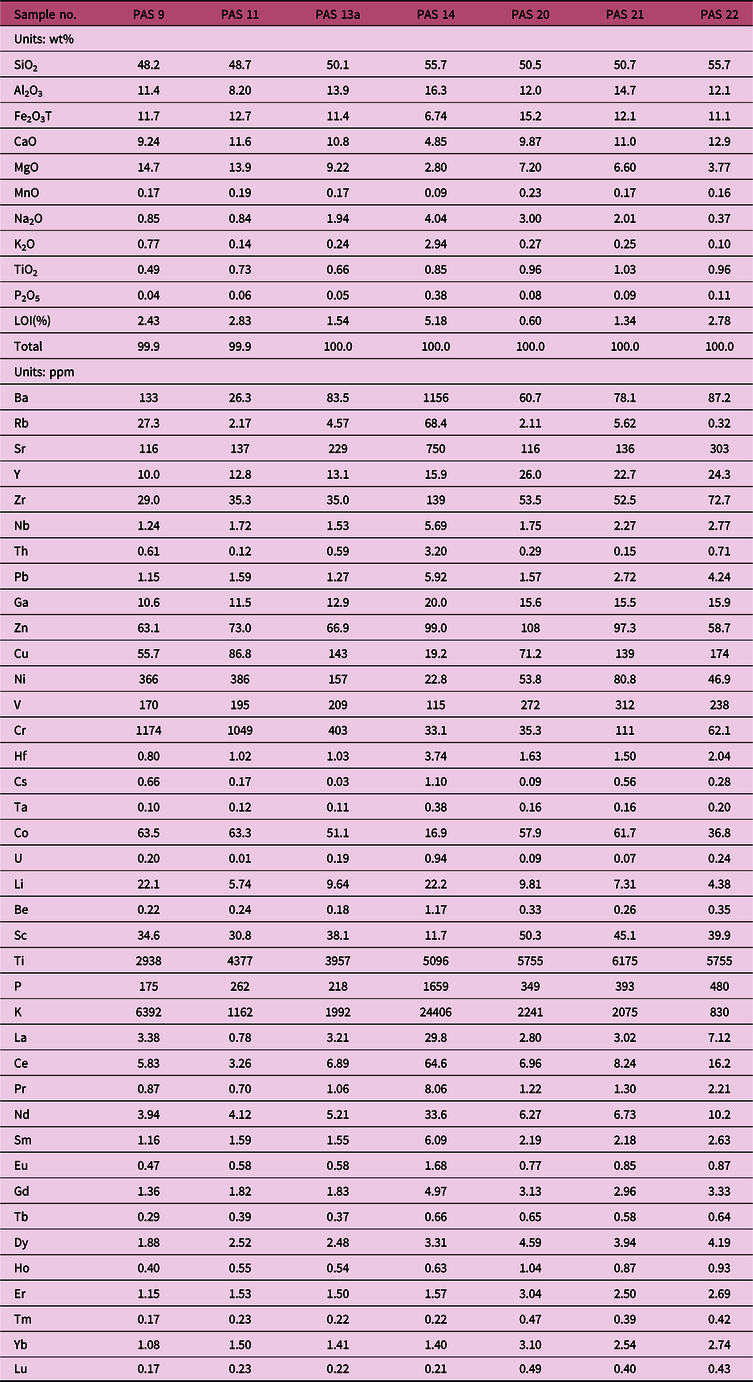

The whole-rock geochemical compositions of the metavolcanic samples are provided in Table 1. The samples have SiO2 contents of 48.2–55.7 wt%, Al2O3 (8.20–16.3 wt%), Fe2O3T (6.74–15.2 wt%), MgO (2.80–14.7 wt%), CaO (4.85–12.9 wt%), Na2O (0.37–4.04 wt%), K2O (0.10–2.94 wt%) and TiO2 (0.49–1.03 wt%). These samples also display a wide range of V, Cr, Ni and Co contents. The V content ranges over 115–312 ppm, Cr of 33.1–1174 ppm, Co of 16.9–63.5 ppm and Ni of 22.8–386 ppm. On the binary diagram of major oxide versus SiO2 (Fig. 4), the metavolcanic rocks display trends of decreasing MgO, CaO, TiO2 and Fe2O3T with progressive increase in SiO2, while Na2O and Al2O3 increase with increasing SiO2 contents. K2O and P2O5 do not produce any defined trend with SiO2 (Fig. 4). The metavolcanics plot dominantly as tholeiites on both the K2O versus SiO2 and AFM (Na2O + K2O – FeOt – MgO) diagrams (Fig. 5a, c) and partly as tholeiites on the Th versus Co diagram (Fig. 5b). The chondrite-normalized rare Earth element (REE) (Fig. 6a) and multi-element (Fig. 6b) patterns of the metavolcanic rocks conform well with normal mid-ocean-ridge basalt (N-MORB) -type magmatism. They contain higher REE concentrations compared with those of chondrite (Fig. 6a); however, from the chondrite-normalized REE diagram (Fig. 6a), four of the metavolcanic rocks show flat but parallel-to-subparallel patterns, with two samples showing light REE (LREE) enrichment and heavy REE (HREE) depletion, while one sample displays depletion in LREE relative to HREE. The samples define weak positive to negative Eu (Eu/Eu* = 0.90–1.14) anomalies. On the N-MORB-normalized diagram (Fig. 6b), the metavolcanic rocks display depletion in Rb, Th, Nb, Ta, Ti and P and enrichment in Ba, U, K and Sr. On the whole, they are enriched in large-ion lithophile elements (LILE) relative to N-MORB; however, their high-field-strength element (HFSE) and HREE concentrations are similar to those of N-MORB.

Table 1. Whole-rock major- and trace-element compositions of the Palaeoproterozoic Birimian metavolcanic rocks from the Lawra Volcanic Belt of Ghana

Fig. 4. Harker diagrams of rocks from the Lawra Volcanic Belt, showing the major elements plotted against SiO2. Most of the major oxides display negative correlation with SiO2.

Fig. 5. (a) K2O versus SiO2; (b) Th–Co diagram of Hastie et al. (Reference Hastie, Kerr, Pearce and Mitchell2007); and (c) AFM diagram of the Lawra metavolcanic rocks and enclaves (Irvine & Baragar, Reference Irvine and Baragar1971). The samples plot within the respective calc-alkaline series, high-K calc-alkaline series and tholeiite series.

Fig. 6. (a, c) Chondrite-normalized REE and (b, d) N-MORB-normalized trace-element patterns for the rocks in the study area. Chondrite-normalizing values are from Boynton (Reference Boynton and Henderson1984), whereas N-MORB-normalizing values are from Sun & McDonough (Reference Sun and McDonough1989). E-MORB and OIB data are from Gale et al. (Reference Gale, Dalton, Langmuir, Su and Schilling2013).

4.b.2. Granitoid-hosted enclaves

The geochemistry of the enclaves is presented in Table 2. The enclaves show significant variations in major-element content. For example, SiO2 contents range from 48.6 to 68.9 wt%, suggestive of their evolved nature. Other oxides are Al2O3 (13.6–16.0 wt%), Fe2O3T (2.97–13.5 wt%), MgO (1.14–9.61 wt%), CaO (2.27–13.8 wt%), Na2O (1.34–4.91 wt%), K2O (0.13–2.67 wt%) and TiO2 (0.50–0.81 wt%). The Ni contents of the enclaves range between 5.26 and 185 ppm, Co 5.54–47.8 ppm, Cr 8.06–492 ppm and V 36.2–168 ppm.

Table 2. Whole-rock major- and trace-element compositions of granitoid-hosted enclaves from the Lawra Volcanic Belt of Ghana

The enclaves generally contain higher values of Fe2O3T, MgO, CaO, MnO, Na2O, TiO2 and P2O5 transition elements (Ni, Cr, Co, V) and lower values of SiO2, K2O, Na2O and Zr than their host (Sakyi et al. Reference Sakyi, Su, Anum, Kwayisi, Dampare, Anani and Nude2014, table 1), consistent with the occurrence of abundant ferromagnesian minerals in the enclaves. These further indicate the crystallization of the enclaves from more mafic magma.

In Figure 4, the enclaves define trends of decreasing MgO, CaO, TiO2 and Fe2O3T with increasing SiO2, whereas Na2O and Al2O3 show positive correlation with SiO2 contents. The plots of K2O and P2O3 against SiO2 do not produce any defined trend (Fig. 4). The enclaves plot mainly as calc-alkaline (Fig. 5a–c). They contain higher REE concentrations compared with those of chondrite, but they generally define enriched LREE patterns relative to HREE with pronounced Eu-negative (Eu/Eu* = 0.57–0.95) anomalies (Fig. 6c), except for one sample that defines a nearly flat REE pattern with weak Eu-positive (Eu/Eu* = 1.21) anomaly. Compared with N-MORB, the enclaves (with the exception of the HREE) are relatively enriched but display features of subduction-related magmatism (Fig. 6d). However, they display positive peaks in Ba, U, K and Sr and negative peaks in Rb, Nb, Ta, La, Ce, P and Ti. Generally, the enclaves have geochemical features that are similar to those of the metavolcanic rocks.

4.c. Sr–Nd isotope geochemistry

The Sr–Nd isotopic data, including 87Sr/86Sr initial ratios and εNd(T) and Nd model ages (T DM1 and T DM2) for the metavolcanic rocks and enclaves are presented in Table 3. The initial 87Sr/86Sr ratios and εNd values were calculated using an age of 2.1 Ga, representing crustal formation during the Eburnean Orogeny (e.g. Abouchami et al. Reference Abouchami, Boher, Michard and Albarede1990; Boher et al. Reference Boher, Abouchami, Michard, Albarède and Arndt1992). The metavolcanic rocks and enclaves show low initial 87Sr/ 86Sr ratios ranging over 0.69868–0.70183 and 0.70126–0.70160, respectively (Table 3). The metavolcanics also show moderate to low positive εNd values of +0.79 to +2.86, while the enclaves have low positive εNd values of +0.79 to +1.82.

Table 3. Rb–Sr and Sm–Nd isotopic compositions of Palaeoproterozoic Birimian metavolcanic rocks and enclaves from the Lawra Volcanic Belt of Ghana. Source of TDM data: DePaolo (Reference DePaolo1981)

Crustal residence age (T DM) of crustal rocks can be calculated by employing diverse models of depleted mantle evolution (e.g. DePaolo, Reference DePaolo1981; Othman et al. Reference Othman, Polvé and Allègre1984; Albarède & Brouxel, Reference Albarède and Brouxel1987; Liew & Hofmann, Reference Liew and Hofmann1988; Blichert-Toft & Albarède, Reference Blichert-Toft and Albarède1997). The Nd model age of crustal rocks indicates their time of extraction from the mantle. It is assumed that a Sm–Nd model age represents an average crustal residence time. However, this assumption is valid only if the crustal material has not experienced any fractionation of Sm/Nd since the first separation of its protolith from the mantle source. As this is not always the case, and there is a need to avoid either overestimation or underestimation of one-stage Nd model ages, a two-stage Nd model age (T DM2) can be calculated for the rocks. We therefore adopted the one-stage (T DM1) and two-stage (T DM2) models of DePaolo (Reference DePaolo1981). DePaolo (Reference DePaolo1981) argued that T CHUR model ages are not reliable and usually miscalculate the true crustal formation ages, and that T DM model ages represent much more accurate ages of crust formation. DePaolo (Reference DePaolo1981) also stated that the crust is derived from a depleted mantle with elevated Sm/Nd ratios (εNd > 0) and not a “primitive” mantle source (εNd = 0); crust formation ages should therefore be calculated relative to the depleted mantle.

The metavolcanic rocks yield T DM1 ages of 2.41–2.76 Ga (except for two samples that yield 4.03–4.28 Ga) and T DM2 ages of 2.31–2.47 Ga. The enclaves yield T DM1 and T DM2 ages of 2.37–2.46 Ga and 2.39–2.47 Ga, respectively (Table 3). Both one-stage and two-stage model ages have their own uncertainties (Dampare et al. Reference Dampare, Shibata, Asiedu, Osae and Banoeng-Yakubo2008). According to Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Zhao, Simon, Wilde and Sun2005), more accurate results could be obtained for the single-stage model age if the Sm/Nd fractionation (ƒSm/Nd) is limited to the range −0.2 to −0.6. In this study, the ƒSm/Nd values of the metavolcanic rocks range from −0.44 to +0.03; those for the enclaves range from −0.48 to −0.05. The inconsistency in the T DM1 ages for the metavolcanic rocks could therefore be explained by the above-mentioned fractionation effect, and these data were not considered further. The two-stage Nd model ages (T DM2) also display a more consistent pattern compared with the single-stage model age (T DM1); T DM2 ages will therefore be used in further discussions.

5. Discussion

5.a. Alteration and effects of weathering

The loss on ignition (LOI) values for the metavolcanic rocks and mafic enclaves are in the range of 0.60–5.18% and 0.65–1.63%, respectively (Tables 1, 2). These values are generally low, suggesting that the samples are relatively fresh. Previous studies have shown that the Birimian rocks have undergone metamorphism mostly under greenschist facies conditions (e.g. Sylvester & Attoh, Reference Sylvester and Attoh1992; Dampare et al. Reference Dampare, Shibata, Asiedu, Osae and Banoeng-Yakubo2008; Amponsah et al. Reference Amponsah, Salvi, Béziat, Siebenaller and Jessell2015, Reference Amponsah, Salvi, Béziat, Baratoux, Siebenaller, Jessell, Nude and Gyawu2016a, b; Block et al. Reference Block, Jessell, Aillères, Baratoux, Bruguier, Zeh, Bosch, Caby and Mensah2016b). Petrographic studies of the samples show that the primary mineral assemblages and textures have not experienced significant alteration. Regardless, we calculated the chemical index of alteration (CIA) (Nesbitt & Young, Reference Nesbitt and Young1982) to determine the extent to which they have been altered by secondary processes. The CIA values obtained are 26.6–47.0 (average, 36.4) for the metavolcanic rocks and 36.4–55.2 (average, 43.8) for the enclaves. According to Nesbitt & Young (Reference Nesbitt and Young1982), the CIA value of unaltered rock is 50 and any CIA value exceeding 60 can be considered as significantly altered. This range of values suggests that the studied samples are relatively fresh and could therefore be relied upon for geochemical investigations. Similarly, the calc-alkaline to high-K calc-alkaline and tholeiite series signatures commonly displayed by the samples on the plots of K2O versus SiO2 (Fig. 5a; Peccerillo &Taylor, Reference Peccerillo and Taylor1976) and transition versus fluid immobile elements (e.g. Co versus Th; Fig. 5b; Hastie et al. Reference Hastie, Kerr, Pearce and Mitchell2007) indicate that the LILE (e.g. K) were least affected by alteration and/or metamorphism. Although the alkali (e.g. K2O and Na2O) values may have been affected by alteration, the LOI and CIA values and inferences made from them strongly indicate they are relatively primary.

5.b. Petrogenesis of the metavolcanic rocks and enclaves

In Figure 5a–c the metavolcanic rocks display mainly tholeiite signatures, whereas the enclaves broadly display calc-alkalic signatures, a reflection of an evolved magma formed in an arc environment. Again, the SiO2 contents of the samples (48.2–68.9 wt%) suggest that some of them are moderately evolved. The parallel to subparallel pattern displayed by the REEs (Fig. 6a, c) agrees with the interpretation that these samples have not undergone any significant fractionation.

The negative trends defined by decreasing CaO, Fe2O3T and MgO with increasing SiO2 content (Fig. 4) indicate that plagioclase and olivine and/or pyroxene were probably the major phases that crystallized out during the evolution of the magma (Yücel et al. Reference Yücel, Arslan, Temizel, Abdioğlu and Ruffet2017). The effects of fractional crystallization on the composition of primary magma and partial melting are sometimes very difficult to differentiate. However, the plots of compatible and incompatible elements can be used to determine the processes that occurred during magma ascent (Dampare et al. Reference Dampare, Shibata, Asiedu, Osae and Banoeng-Yakubo2008). This is because the fractionation of ferromagnesian minerals such as pyroxene and olivine decreases the concentrations of compatible elements (e.g. Ni and Cr) and increases the concentration of incompatible elements (e.g. Th, La and Nd) in the liquids (Dampare et al. Reference Dampare, Shibata, Asiedu, Osae and Banoeng-Yakubo2008). On the plot of Ni (compatible element) and Th (incompatible element) versus SiO2 (Fig. 7a, b), there is a decrease in Ni and slight increase in Th with increasing SiO2 content. This suggests that the metavolcanic rocks and enclaves might have undergone minor fractional crystallization during their evolution (Dampare et al. Reference Dampare, Shibata, Asiedu, Osae and Banoeng-Yakubo2008). The decrease in Ni content with increasing SiO2 content indicates that olivine was probably the primary phase that fractionated out of the melt (Yücel et al. Reference Yücel, Arslan, Temizel, Abdioğlu and Ruffet2017).

Fig. 7. Trace-element variations with respect to SiO2 for the Lawra metavolcanic rocks and enclaves: (a) compatible element (Ni) variation with SiO2; and (b) incompatible element (Th) variation with SiO2.

Constant Th/Nb and Nb/Yb values are characteristics of basaltic rocks derived from the mantle lithosphere, the plume asthenosphere or depleted MORB mantle. In a plot of Th/Yb versus Nb/Yb, such basaltic rocks usually plot in or around the diagonal mantle array (Pearce, Reference Pearce, Hawkesworth and Norry1983, Reference Pearce2014; Pearce & Peate, Reference Pearce and Peate1995). In the plot of Th/Yb versus Nb/Yb discrimination diagram, after Pearce (Reference Pearce, Hawkesworth and Norry1983) (Fig. 8), all the samples display high Th/Yb ratios relative to that of the mantle array, with all but two of the metavolcanics samples plotting above the N-MORB/ocean island basalt (OIB) array. One enclave sample, with a Th/Yb value of 30, falls outside the range of values for the plot. The trend displayed by the metavolcanic rocks and the enclaves suggests arc-related magmatism (Pearce, Reference Pearce2008). Subduction-zone-related fluids often entrain Th relative to Nb, Ta or Yb, which signifies that Th, rather than Nb or Ta, would be enriched in source components that have been metasomatized by subduction processes, resulting in elevated Th/Yb ratios relative to Nb/Yb or Ta/Yb. Equally, crustal rocks are characterized by higher contents of Th compared to Nb and Ta. The higher Th/Yb values for both the enclaves and metavolcanic rocks may therefore indicate crustal assimilation during the evolution of the magma, or may be attributed to the enrichment of the mantle (source region) by a subducted component carrying Th but not Ta or Yb (Pearce et al. Reference Pearce, Bender, De Long, Kidd, Low, Güner, Saroglu, Yilmaz, Moorbath and Mitchell1990). Our results are consistent with the latter process.

Fig. 8. Th/Yb versus Nb/Yb diagram (after Pearce, Reference Pearce, Hawkesworth and Norry1983; Pearce & Peate, Reference Pearce and Peate1995) of the metavolcanic rocks and enclaves. WPE – within-plate enrichment; SZ – subduction zone flux; CC – crustal contamination. N-MORB, E-MORB and OIB values from Sun & McDonough (Reference Sun and McDonough1989).

The metavolcanic rocks and enclaves display low initial 87Sr/ 86Sr ratios of 0.698679–0.701831 and 0.701261–0.701600, respectively. Earlier studies on Birimian rocks in Ghana and the rest of West Africa (e.g. Abouchami et al. Reference Abouchami, Boher, Michard and Albarede1990; Boher et al. Reference Boher, Abouchami, Michard, Albarède and Arndt1992; Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Moorbath, Leube and Hirdes1992; Gasquet et al. Reference Gasquet, Barbey, Adou and Paquette2003; Dampare et al. Reference Dampare, Shibata, Asiedu, Osamu, Manu and Sakyi2009) have produced a wide range of initial 87Sr/86Sr ratios, ranging from as low as 0.65300 to 0.70623. The values obtained in this study fall within the range of values in previous studies, indicating that low (87Sr/86Sr)i is typical of Birimian rocks in West Africa. Gasquet et al. (Reference Gasquet, Barbey, Adou and Paquette2003) and Dampare et al. (Reference Dampare, Shibata, Asiedu, Osamu, Manu and Sakyi2009) attributed the low initial 87Sr/86Sr ratios to feldspar alteration and metamorphism. Petrographic observation of our samples further revealed that the feldspars are partially or wholly altered to sericite, epidote and calcite. We therefore do not place too much emphasis on the (87Sr/86Sr)i ratio in our discussion. The positive εNd (2.1 Ga) values of +0.79 to +2.86 for the metavolcanic rocks and +0.79 to +1.82 for the enclaves support the role of juvenile components in their genesis, indicating the significant input of new mantle-derived magmas. The juvenile nature of the samples is established in Figure 9a, where they plot close to the depleted mantle curve and are also widely separated from the Nd isotopic evolutionary trend of Archean crust. The positive εNd values for some of the rocks suggest their derivation from a depleted mantle source (Srivastava et al. Reference Srivastava, Ellam and Gautam2009). The range of initial εNd values from our samples strongly suggests that the rocks were produced entirely from the mantle in an oceanic setting (DePaolo, Reference DePaolo1988), with possible minor crustal contamination.

Fig. 9. (a) Plot of εNd (2.1 Ga) versus formation age (time) for the Palaeoproterozoic metavolcanic rocks and enclaves from the study area. Data for Archean continental crust are from Kouamelan et al. (Reference Kouamelan, Peucat and Delor1997). (b) εNd (2.1 Ga) versus initial 87Sr/86Sr ratios (calculated at 2.1 Ga) plot for the Palaeoproterozoic metavolcanic rocks and mafic enclaves from the study area. Also shown is the field of isotopic composition of Birimian basaltic and felsic rocks (shaded area) from the WAC (adapted from Pawlig et al. Reference Pawlig, Gueye, Klischies, Schwarz, Wemmer and Siegesmund2006). DM represents contemporaneous depleted mantle from Othman et al. (Reference Othman, Polvé and Allègre1984).

In Figure 9b, the samples plot almost exclusively within the field defined by Birimian basalts and granitoids and this, coupled with the low and restricted (87Sr/86Sr)i values and low positive initial εNd(T) values, suggests that the metavolcanic rocks and enclaves have isotopic characteristics similar to rocks from other Birimian terranes in Ghana and West Africa (e.g. Abouchami et al. Reference Abouchami, Boher, Michard and Albarede1990; Boher et al. Reference Boher, Abouchami, Michard, Albarède and Arndt1992; Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Moorbath, Leube and Hirdes1992; Gasquet et al. Reference Gasquet, Barbey, Adou and Paquette2003; Dampare et al. Reference Dampare, Shibata, Asiedu, Osamu, Manu and Sakyi2009). The Birimian basins and belts are intruded by different generations of granitoids (e.g. Agyei Duodu et al. Reference Agyei Duodu, Loh, Boamah, Baba, Hirdes, Toloczyki and Davis2009; Sakyi et al. Reference Sakyi, Su, Anum, Kwayisi, Dampare, Anani and Nude2014; Block et al. Reference Block, Baratoux, Zeh, Laurent, Bruguier, Jessell, Aillères, Sagna, Parra-Avila and Bosch2016a). However, the granitoid-hosted enclaves display an identical composition to that of the metavolcanic rocks. The mineralogical and geochemical features of the enclaves and metavolcanics support the idea that the granitoid rocks developed through variable degrees of mixing/mingling between a basic magma and granitic melt during subduction, when blobs of basic to intermediate parental magma became trapped in the granitic magma (Hassen et al. Reference Hassen, Rasmy El-Gharbawy, El-Masry and Buda2008; Rajaieh et al. Reference Rajaieh, Khalili and Richards2010). The gabbro and andesite enclaves most likely represent the nearest composition to the original, more basic, magma.

The two-stage (T DM2) Nd model ages of 2.31–2.47 Ga for the metavolcanic rocks and 2.39–2.47 Ga for the enclaves are higher than the formation age of 2.1 Ga, suggesting that they may have received some inputs from older crustal sources. However, the trace-element data of the studied samples are not consistent with crustal contamination. For example, the negative Nb–Ta anomalies could be attributed to crustal contamination; however, the negative Zr–Hf anomalies displayed by the rocks are inconsistent with crustal contamination, since crustal materials are enriched in elements such as Th, Zr and Hf. Since negative Zr–Hf anomalies are uncommon among intraplate basalts (Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Kennedy, Sun, Malpas and Lesher2002), we ascribe the Nb–Ta and Zr–Hf depletions to a lack of an OIB component in the source region of the rocks. The metavolcanic rocks and enclaves may therefore have been derived from lithospheric mantle sources.

Several recent studies have revealed the existence of older crustal materials in parts of the WAC. For example, SHRIMP U–Pb geochronological studies on zircons from granitoids in the Bolé–Wa region of NW Ghana (de Kock et al. Reference de Kock, Armstrong, Siegfried and Thomas2011) produced inherited ages of 2876 and 2499 Ma, showing that continental crust was involved until the generation of the Gondo granite within the Bolé–Navrongo Belt. Petersson et al. (Reference Petersson, Scherstén, Kemp, Kristinsdóttir, Kalvig and Anum2016) conducted zircon U–Pb age dating and Lu–Hf isotopic systematics on granitoids from southern Ghana, and revealed zircon with an 207Pb/206Pb age of 2460 Ma, interpreted to be of xenocrystic origin. Similarly, in situ zircon U–Pb dating and Lu–Hf isotope analyses carried out on inherited zircons in granitoids from northern Ghana yielded ages of 2220–2360 Ma (Block et al. Reference Block, Baratoux, Zeh, Laurent, Bruguier, Jessell, Aillères, Sagna, Parra-Avila and Bosch2016a). Parra-Avila et al. (Reference Parra-Avila, Baratoux, Eglinger, Fiorentini and Block2019) inferred that the eastern part of the Baoulé–Mossi domain is underlain by Archean rocks, giving rise to predominately older ages (c. > 2100 Ma). Thiéblemont et al. (Reference Thiéblemont, Delor, Cocherie, Lafon, Goujou, Baldé, Bah, Sané and Mark Fanning2001) recorded U–Pb ages of 3542 and 3535 Ma for the granite–gneiss association in the Archean Kenema–Man domain of Guinea, and the late Eburnean plutonic belt of eastern Guinea is a key element of the Archean–Proterozoic transition zone in the southern part of West Africa (Egal et al. Reference Egal, Thiéblemont, Lahondére, Guerrot, Costea, Iliescu, Delor, Goujou, Lafon, Tegyey, Diaby and Kolie2002).

Additionally, a Sm–Nd model age of c. 2600 Ma was obtained from Winneba granitoids in Ghana (Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Moorbath, Leube and Hirdes1992). More recently, Petersson et al. (Reference Petersson, Scherstén, Kemp, Kristinsdóttir, Kalvig and Anum2016) obtained Hf model ages of 2.4–2.7 Ga for granites from southern and southwestern Ghana. Also, a recent study based on Lu–Hf isotopic systematics revealed that the crust of the western Baoulé–Mossi domain has Hf model ages of 2.80 Ga, indicating possible reworking of older crust in parts of the WAC (Parra-Avila et al. Reference Parra-Avila, Belousova, Fiorentini, Baratoux, Davis, Miller and McCuaig2016). Similarly, Block et al. (Reference Block, Baratoux, Zeh, Laurent, Bruguier, Jessell, Aillères, Sagna, Parra-Avila and Bosch2016a) produced two-stage Hf model ages of 2.35–2.61 Ga in zircons from granitoids of the Bole–Bulenga, Abulembire, Bawku and Koudougou–Tumu domains in northern Ghana. The abovementioned studies provide strong evidence that the Palaeoproterozoic Birimian Terrane of the WAC is underlain by Archean rocks. The model ages obtained here therefore support the juvenile character of the rocks, with the contribution of subducted pre-Birimian rocks (or Archean?) in the source material. We propose that magma for the studied rocks was derived from mantle source(s) modified by subducted materials.

5.c. Tectonic setting of the metavolcanic rocks and enclaves

Previous studies of the Palaeoproterozoic rocks have proposed different models to explain the tectonic setting of the rocks; namely the island-arc setting (Sylvester & Attoh, Reference Sylvester and Attoh1992; Béziat et al. Reference Béziat, Bourges, Debat, Lompo, Martin and Tollon2000; Attoh et al. Reference Attoh, Evans and Bickford2006; Feybesse et al. Reference Feybesse, Billa, Guerrot, Duguey, Lescuyer, Milési and Bouchot2006; Dampare et al. Reference Dampare, Shibata, Asiedu, Osae and Banoeng-Yakubo2008) and plume-related setting (e.g. Abouchami et al. Reference Abouchami, Boher, Michard and Albarede1990; Lompo, Reference Lompo, Reddy, Mazumder, Evans and Collins2009). From the petrographic analyses, we observed that the rocks have undergone various degrees of alteration. It has also been reported in the literature (e.g. Hirdes et al. Reference Hirdes, Davis and Eisenlohr1992; Attoh et al. Reference Attoh, Evans and Bickford2006) that rocks of the Palaeoproterozoic Birimian have undergone greenschist facies metamorphism. These processes and alterations affect the distribution of the LILE and mean that the application of most major-element oxides and LILE for identifying tectonic setting of the metavolcanic rocks and enclaves is unreliable. Accordingly, the more resistant HFSE, including Nb, Zr, Ti, Y, Sr, La, Hf, Ta and Yb, have been used in determining the tectonic setting of the samples (Girty et al. Reference Girty, Thomson, Girty, Bracchi and Miller1994).

The metavolcanic rocks and enclaves (Tables 1, 2) have very low TiO2 (<2.0 wt%) and are therefore inferred to represent igneous rocks from magmatic arcs (Pearce, Reference Pearce2014), which typically have low TiO2. On the spider diagrams (Fig. 6b, d), the metavolcanic rocks and enclaves are characterized by positive Ba and Th anomalies and negative Nb–Ta, Zr–Hf and Ti anomalies, which are geochemical features that may connote the formation of the rocks in an arc setting (Fitton et al. Reference Fitton, James, Kempton, Ormerod and Leeman1988; Saunders et al. Reference Saunders, Norry and Tarney1988). Our data therefore suggest subduction-related magmatism, and are consistent with an island-arc setting (Sylvester & Attoh, Reference Sylvester and Attoh1992; Béziat et al. Reference Béziat, Bourges, Debat, Lompo, Martin and Tollon2000; Attoh et al. Reference Attoh, Evans and Bickford2006; Dampare et al. Reference Dampare, Shibata, Asiedu, Osae and Banoeng-Yakubo2008) rather than the proposed plume-generated setting (e.g. Abouchami et al. Reference Abouchami, Boher, Michard and Albarede1990) for the Palaeoproterozoic rocks of West Africa.

The tectonic setting of the metavolcanic rocks and enclaves was investigated using the tectonic discrimination diagram of Wood (Reference Wood1980) (Fig. 10a). On this diagram, the samples plot in the fields of calc-alkaline basalts (CAB), island-arc tholeiites (IAT) and N-MORB, supporting the interpretation that they were derived from an arc environment. The relative ratio of V and Ti can also be used to discriminate the tectonic environment of different types of basalts as proposed by Shervais (Reference Shervais1982). In Figure 10b, the samples fall within the CAB–MORB–volcanic-arc basalt (VAB) overlap field, also indicating possible subduction-related magmatism. Further, on the plot of ƒSm/Nd versus εNd (2.1 Ga) (Fig. 10c), our samples plot almost exclusively within the field defined by arc rocks. This is consistent with the major- and trace-element data and supports the arc setting for the metavolcanic rocks and enclaves.

Fig. 10. Discriminant diagrams indicating tectonic settings for the studied metavolcanic rocks and enclaves: (a) Hf–Th–Ta by Wood (Reference Wood1980), (b) V versus Ti plot of Shervais et al. (Reference Shervais1982); and (c) plot of εNd (2.1 Ga) versus fractionation parameter (ƒSm/Nd) for the metavolcanic rocks and enclaves from the study area. Fields of old (Archean) continental crust, MORB and the arc rocks are from Roddaz et al. (Reference Roddaz, Debat and Nikiéma2007), defining the tectonic setting of the studied rocks.

6. Conclusion

We have determined the petrography, geochemical and Sr–Nd isotope compositions of mafic metavolcanic rocks and mafic enclaves from the Palaeoproterozoic Lawra Belt in Ghana. The following conclusions can be made from our study.

The metavolcanic rocks are mainly meta-basalts and meta-andesites, while the enclaves are diorites and gabbros. Generally, the metavolcanic rocks and enclaves display identical geochemical and isotopic signatures, suggesting their derivation from the same source.

The host granitoids developed through mixing/mingling between a basic magma and granitic melt, during which globules of basic to intermediate parental magma got trapped in the granitic magma.

The very low TiO2 (<2.0 wt%), pronounced Nb–Ta troughs, enrichment in Ba and Th as well as depletion of Ti of the metavolcanic rocks and enclaves are characteristic of subduction-related magmatism; these characteristics therefore indicate formation in an arc setting. The metavolcanic rocks and enclaves plot in the overlapping field CAB–IAT–N-MORB, also indicating possible subduction-related magmatism. The ƒSm/Nd versus εNd diagram shows that the samples plot almost exclusively within the field defined by arc rocks. All these support the arc affinity for the metavolcanic rocks and enclaves.

The metavolcanic rocks and enclaves are represented by low (87Sr/ 86Sr)i values of 0.69868–0.70183 and 0.70126–0.70160, respectively, a typical characteristic of Birimian rocks in Ghana and the rest of West Africa. This signature is ascribed to feldspar alteration. The rocks also show positive εNd values of +0.79 to +2.86 for the metavolcanic rocks and +0.79 to +1.82 for the enclaves, all indicating that the Birimian crust was most likely formed from juvenile mantle-derived magmas. On a plot of Th/Yb versus Nb/Yb, the rocks show high Th/Yb ratios relative to that of the mantle array, suggesting possible crustal contamination of these rocks.

The Nd model ages (T DM2) of 2.31–2.47 Ga for metavolcanic rocks and 2.39–2.47 Ga for the enclaves support the juvenile character of the rocks with a contribution from subducted pre-Birimian rocks (or Archean?) in the source material.

The metavolcanic rocks and enclaves of the WAC in northwestern Ghana could be interpreted to have been formed in a common island-arc setting.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Solomon Anum of the Ghana Geological Survey Authority, Accra, for providing logistical support and help during fieldwork. We are grateful to Xindi Jin, Ding-Shuai Xue and Wenjun Li of the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for the elemental analyses. This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 41772055 and 91755205) and State Key Laboratory of Lithospheric Evolution (Grant 201701) made available to BXS.

Declaration of Interest

None.